1. Introduction

316L austenitic stainless steel (ASS) has excellent mechanical properties and corrosion resistance [

1,

2,

3], which has found many applications including those in the bio-medical field, e.g., artificial joints, spinal fixation fixtures, orthopedic screws and wires, and dental implants, etc. [

4,

5]. The industrial applications of stainless steel are numerous, such as tubes used for oil and gas transport, petrochemicals, refineries, and conveying tubes, because of its excellent resistance to corrosion and oxidation [

6,

7,

8].

There are several groups of materials used to make orthodontic and orthopedic implants, including chromium and cobalt alloys, austenitic stainless steels, ceramic materials, polymer materials, and popular titanium and its alloys [

9,

10]. Metallic materials are generally stronger than hard tissues, so bio-corrosion and biocompatibility are more concerned with metallic materials for biomedical applications. Williams [

10] suggested that three types of corrosion may exist for dental implants:

Stress cracking (SCC);

Galvanic corrosion (GC);

Erosion corrosion (FC);

Several methods are used to produce ultra-fine-grain (UFG) alloys, achieved by severe plastic deformation (SPD), such as high-pressure torsion, accumulative roll bonding, and equal channel angular pressing (ECAP) [

11,

12]. ECAP is widely used for producing ultrafine grains with sizes in the range of several tens of nanometers to 500 nanometers [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], which helps improve their mechanical properties [

18,

19].

D.M. Xu et al. [

20] reported that a significant fraction of austenite transformed into martensite after 90% cold reduction. The martensite laths were oriented along the rolling direction. The UFG 316LN austenitic stainless steel exhibited excellent mechanical properties of high yield strength and high plasticity.

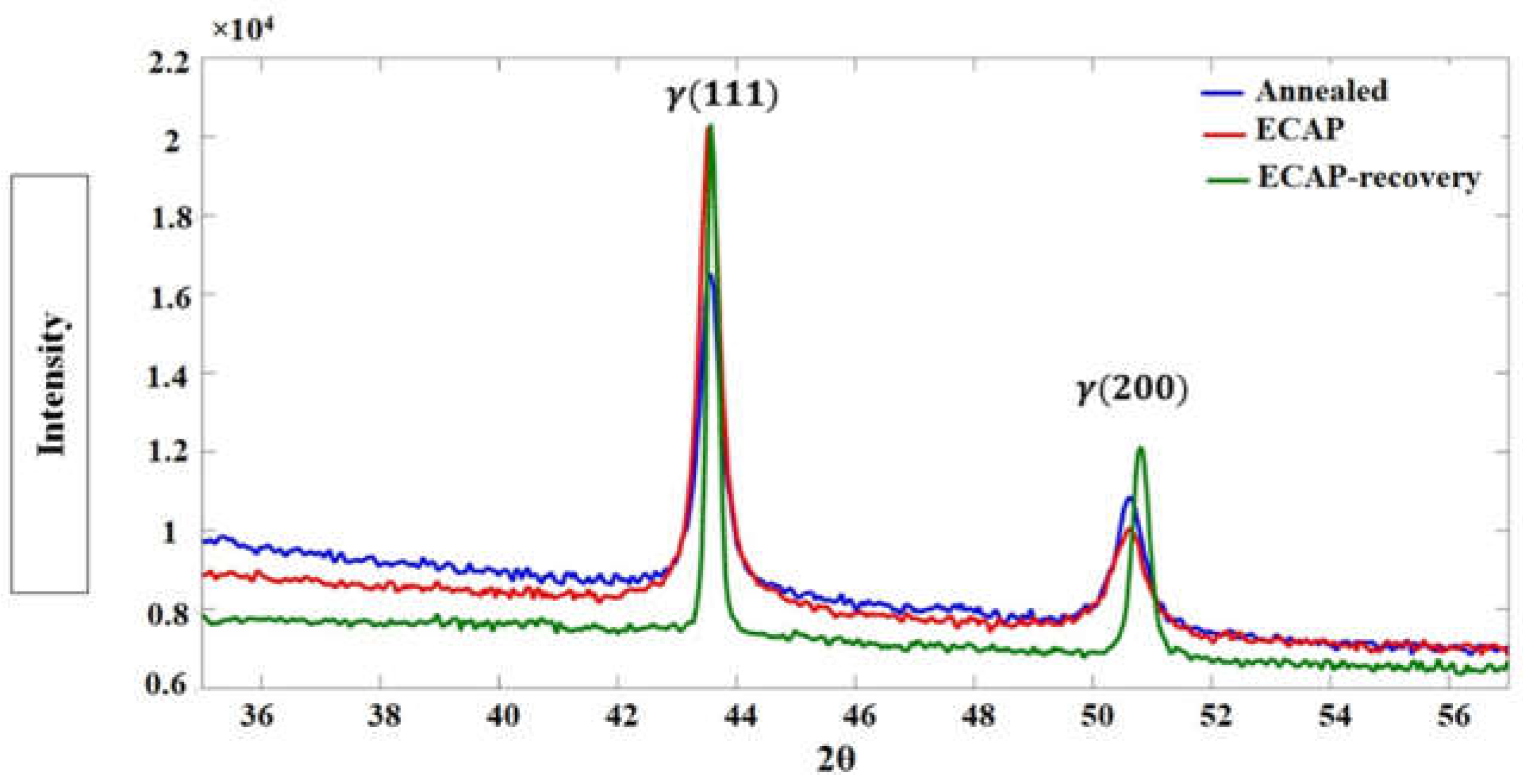

Hajizadeh et al. [

21] studied the ECAP effect on the microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L. They found that due to the high stability of the austenite phase in the studied steel, deformation-induced martensite (DIM) was not observed in samples that experienced ECAP using any of the above routes. Based on the X-ray diffraction analysis, the structure after ECAP is completely austenitic. They reported that as-received material showed a very wide range of work hardening, while such a range for the ECAP samples was narrowed.

Guilherme et al. [

22] investigated the corrosion behavior of UFG Aluminum alloy. They reported that ECAP processing enhances the passive corrosion resistance compared to the undeformed sample. However, the improvement in corrosion resistance did not consistently increase with the number of ECAP passes. Factors such as the distribution of high- and low-angle grain boundaries, dislocation density, and fragmentation and redistribution of coarse dispersoid particles play a significant role in the corrosion behavior post-ECAP.

Awang et al. [

23] reported that finer and elongated grains were achieved in 316L after the ECAP process with correspondingly increased hardness. Their findings showed an improvement in the corrosion behavior of ECAP samples in both 0.9% NaCl and E-MEM + 10% NCS.

Xiaoqian Fu et al. [

24] investigated the effect of grain size on the corrosion resistance of rolled 316L and reported that grain uniformity and intermetallic grain boundary benefited the stability of passive films. There are considerable stress concentrations at grain boundaries after rolling, which can be reduced by annealing. The more the grain boundaries, the higher the pitting potential. SenSen Xin et al. [

25] studied the temperature and grain size effect on the corrosion behavior of 316L stainless steel in seawater. They showed that fine and coarse grains of 316L stainless steel showed nearly the same corrosion resistance at 25℃. However, the pitting resistance of the fine-grain steel was reduced greatly and showed lower pitting potential values in comparison with the coarse-grain one. Roston et al. [

26] reported that the grain refinement improved the corrosion resistance of some alloys such as Mg and Ti. For the other materials, it increased and decreased depending on processing and environment. The reasons that grain refinement improved the corrosion resistance is attributed to an improvement in passive film formation and adhesion because of increasing grain boundary density, but discrepancy exists.

X.Y. Wang et al. [

27] investigated a nano-crystalline surface of 304 stainless produced by sandblasting and recovery heat treatment. They reported that the nano-crystalline surface showed better corrosion resistance, wear, and corrosive wear properties than the as-received one. Research on metals reported that ECAP improved wear resistance but some research showed opposite results after the ECAP process [

28]. For example, it was shown that the improvement in wear resistance of pure Ti and TiNi alloy after the ECAP process [

29,

30]. However, it was also reported that the dual-phase steel with ultra-fine grain showed a higher wear rate than the coarse-grained one [

31]. Nagaraj et al. [

30] investigated the effect of ECAP on the microstructure and tribo-corrosion characteristics of 316L stainless steel. They found that the 4th pass sample showed minimum wear volume loss and a low coefficient of friction during the tribo-corrosion test due to refined grains that show high resistance to plastic deformation. The open circuit potential (OCP) curve of ECAP-processed samples shifts to a more negative potential.

As shown above, the reported studies are not always consistent, implying that the effect of ECAP on wear, corrosion, and corrosive wear has not been fully understood. Severe plastic deformation (SPD) introduces high-density dislocations cells, which harden the materials but make them more susceptible to corrosion or electrochemical attacks. The recovery treatment can turn the nano-scaled dislocations cells into nano-grains, thus increasing not only the hardness but also the resistance to corrosion [

27]. Much research already investigated the effect of the ECAP process on 316L properties. This study was conducted to investigate how the ECAP process affects material properties, including mechanical, tribological, and electrochemical properties for further understanding of the mechanism behind it. In particular, efforts were made to understand the effects of subsequent recovery treatment (at low temperatures) on microstructure, and the properties of 316L were, to fabricate 316L steel with optimal properties for bio-medical and industrial applications.

2. Materials and Methods

For this study, 316L steel is used in rod form with a diameter of 4mm. The chemical composition of material is shown in

Table 1.

The as-received steel was in an austenite state and annealed at 1050℃ for 2 hours in an Argon atmosphere (to prevent oxidation) to achieve a homogenous microstructure and it cooled in the furnace [

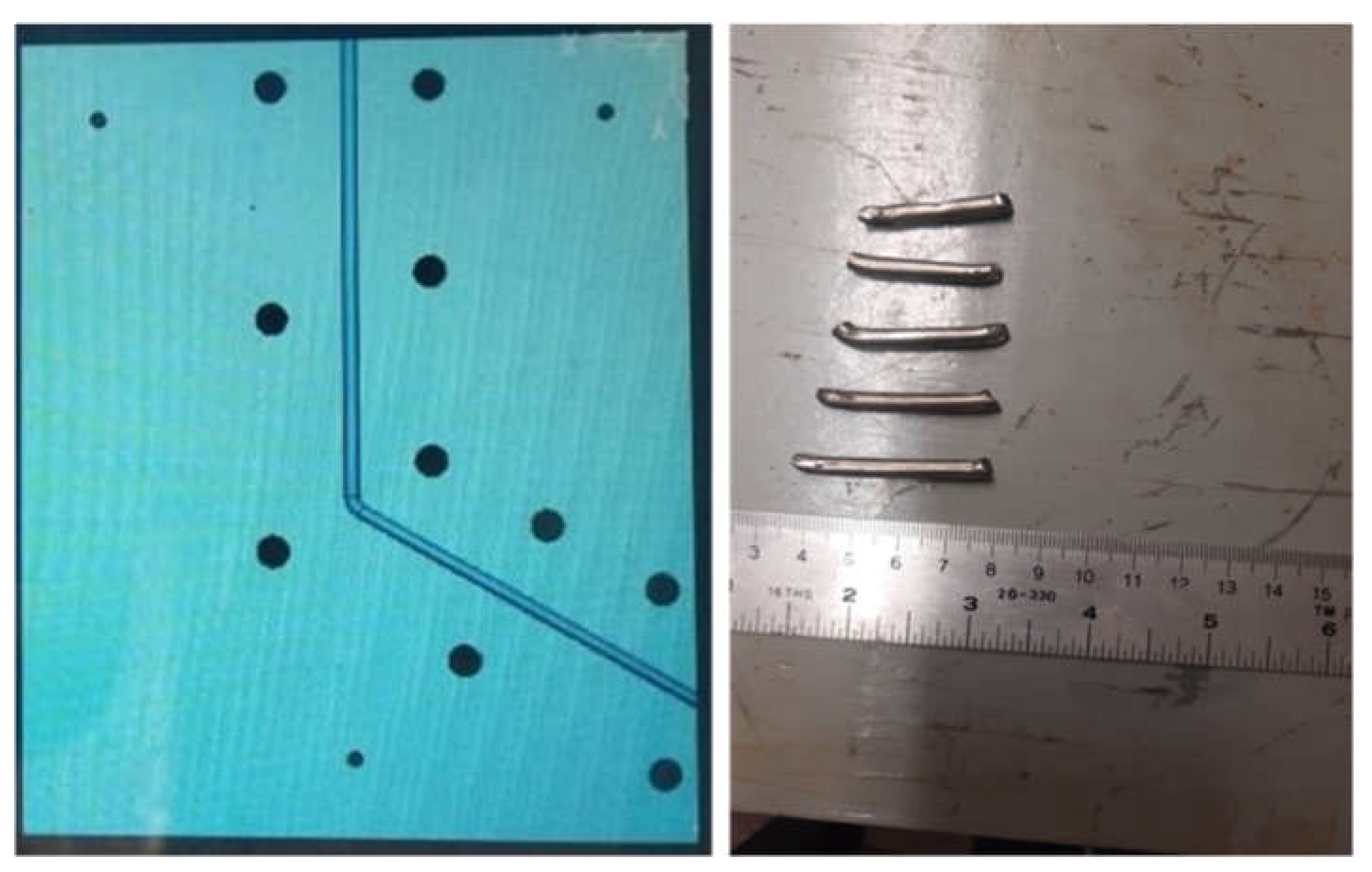

33]. The Equal Channel Angular-Pressing (ECAP) was performed at room temperature by a 50-ton hydraulic press. Graphite powder was used as the lubricant to decrease the friction coefficient between samples and die. Samples after two ECAP passes are shown in

Figure 1. To gain optimal grain refinement, the Bc route was used based on previous research [

11]. The inner contact angle was 120 degrees, while the outer arc of curvature was 60 degrees. Some of the ECAP samples were then heat treated, i.e. recovery treatment at 340℃ for 1 hour in the Argon atmosphere, followed by cooling in the furnace. For microstructure observation, samples were polished with sandpaper and then etched with Aqua regia solution (Nitric acid and Hydrochloric acid in a molar ratio of 1:3). Microstructure characterization and grain size measurement were carried out by optical microscopy (OM), and then by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for more details including microstructure and dislocations density analysis. A JEOL-JEM 2100 equipped with a Gatan imaging filter operated at 200 KV was used for the TEM analysis. TEM foils were prepared by mechanical grinding followed by electrochemical polishing.

The X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted using a D8-Bruker machine for phase detection. The peak profiles were analyzed using Xpert Highscore software.

For evaluation of the mechanical properties, the compressive test and hardness tests were performed, respectively. The hardness test was done under a 100 kg load. The sample diameter and length for compression tests were 4mm and 7mm, respectively. The compression test was carried out with 0.05mm/min and each alloy were tested three times to ensure reproducibility. One of the reasons for using compressive tests to evaluate the mechanical properties of the samples is the consideration that dental implants may bear more compressive force, which could be predominant. Yield stress, max stress (i.e. the stress peak before failure), and energy absorption up to strain of 70% (samples didn’t fail till the maximum load of the machine) were determined for the three samples.

For corrosion behavior analysis, electrochemical tests were performed, including measurements of Open Circuit Potential (OCP) and potentiodynamic polarization, using GAMS within a standard three-electrode setup. The setup consists of a platinum sheet as the counter electrode, a calomel electrode as the reference, and a working electrode with a 0.4 cm² surface area. Potentiodynamic polarization curves were obtained over a potential range of -0.5 to +1.5V relative to OCP, employing a rate of 0.33 mV/s. The corrosion experiments were performed in both 3.5% NaCl solution and 5% HCl solution at room temperature. The NaCl solution simulates a chloride-containing environment, while the HCl solution simulates a low-pH environment. The electrochemical tests were carried out at least three times for data reproducibility.

The wear resistance of a sample was investigated using an R-tec tribo-meter. During the test, a four-sided pyramidal Vickers diamond tip reciprocally scratched the surface at a velocity of 0.5mm/sec for 20 min under different applied loads, 10 and 20 N. The material loss was determined by measuring the volume loss in the worn region using a profilometer. Corrosive wear tests were performed with the same tribo-meter using a ceramic ball tip of 6mm in diameter under a force of 5N. The corrosive wear tests were performed in 5%HCl and 3.5% NaCl. In addition, dry wear tests were also performed with the ceramic ball tip to compare the results of the corrosive wear and dry wear tests.

3. Results

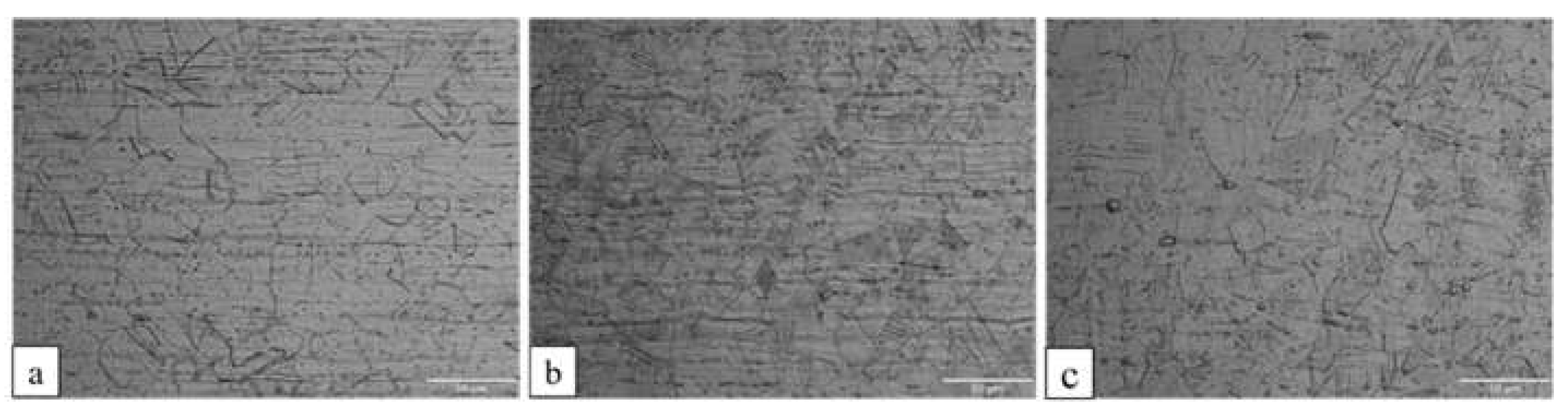

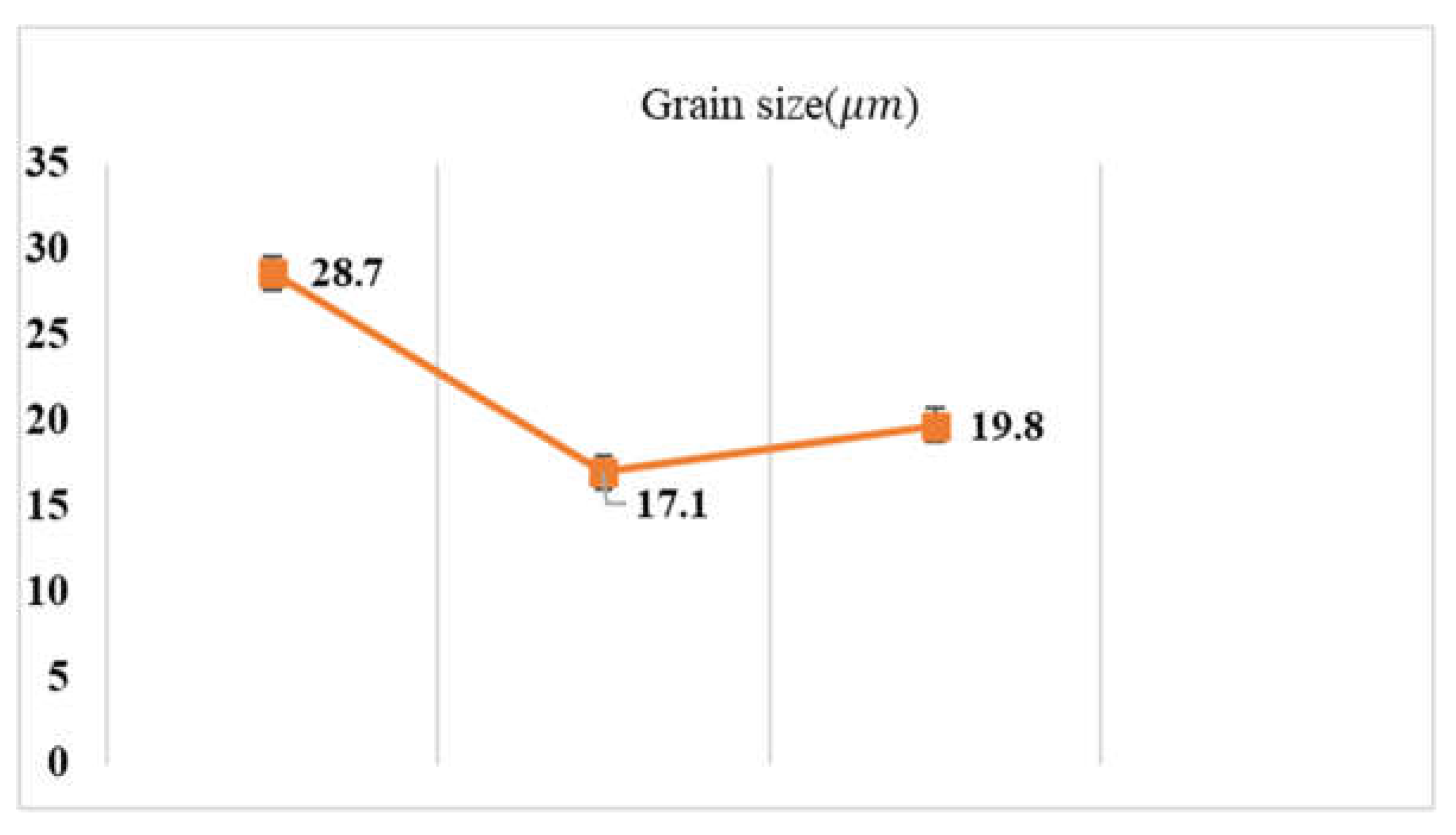

Figure 2 shows the OM images of steel samples in three states after etching, which are mainly in the austenite phase. The images show that twins were created by the ECAP process. Corresponding changes in grain size for the three samples are shown in

Figure 3. As observed, the grain size is decreased by the ECAP process, which slightly increases by the subsequent recovery treatment.

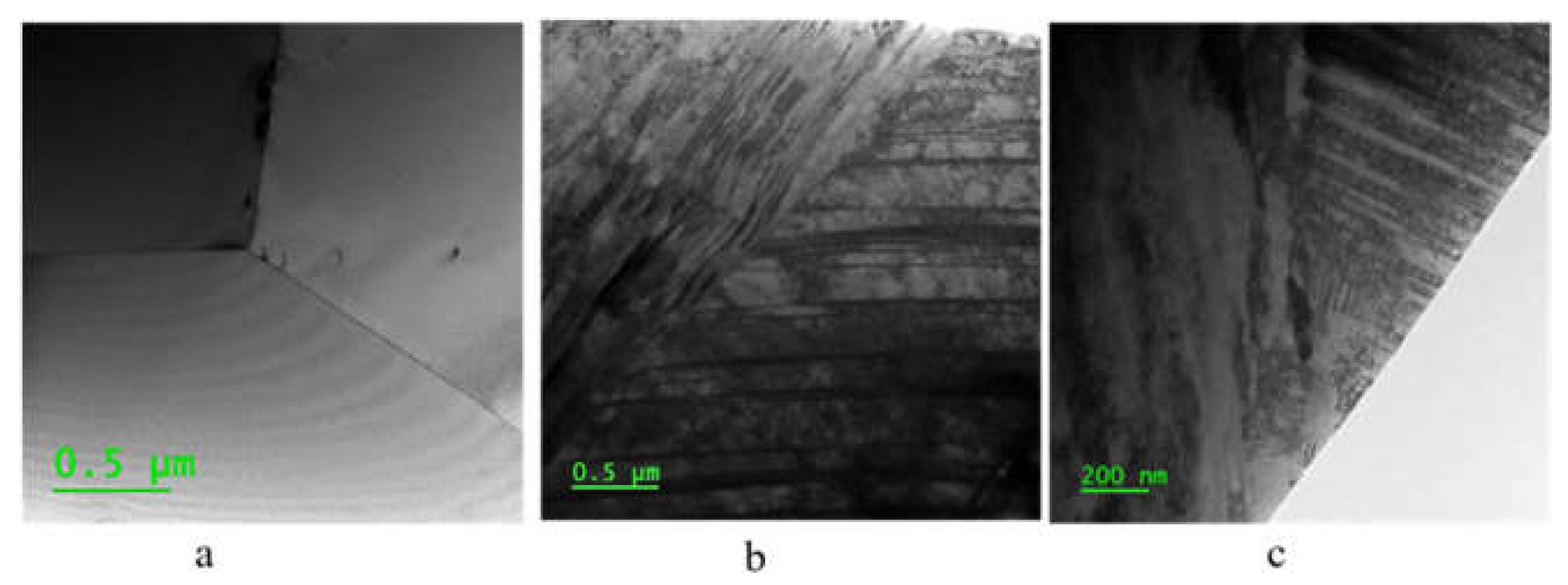

For more detailed information on structure and microstructure such as dislocations density, twins, and the possibility of new phase forming, TEM analysis was conducted.

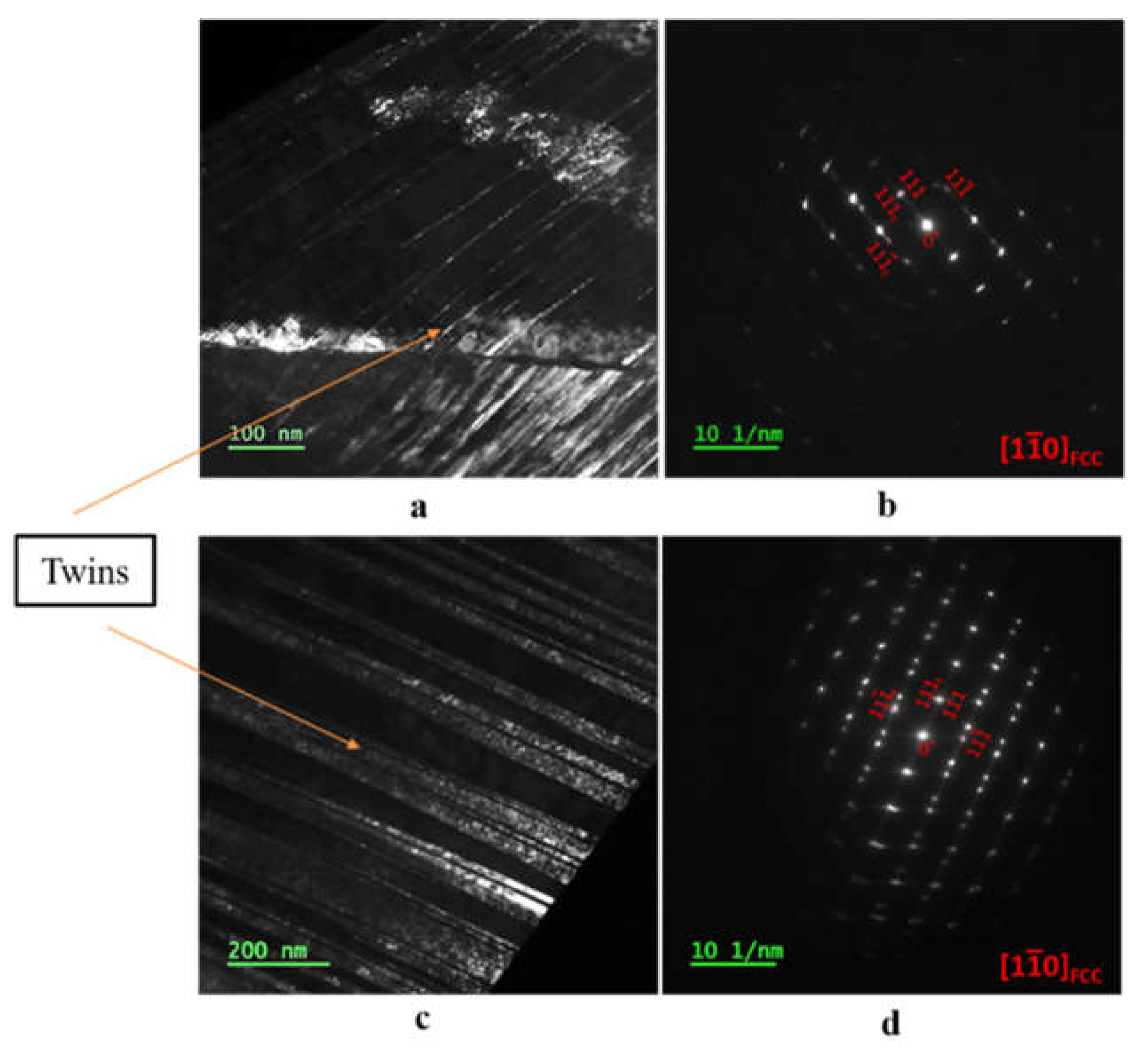

Figure 4 displays TEM images of the three samples, showing that the ECAP introduced deformation twins in the austenite structure of the steel (see

Figure 5), which remain in the steel after the recovery treatment. No phase deformation was observed after the ECAP.

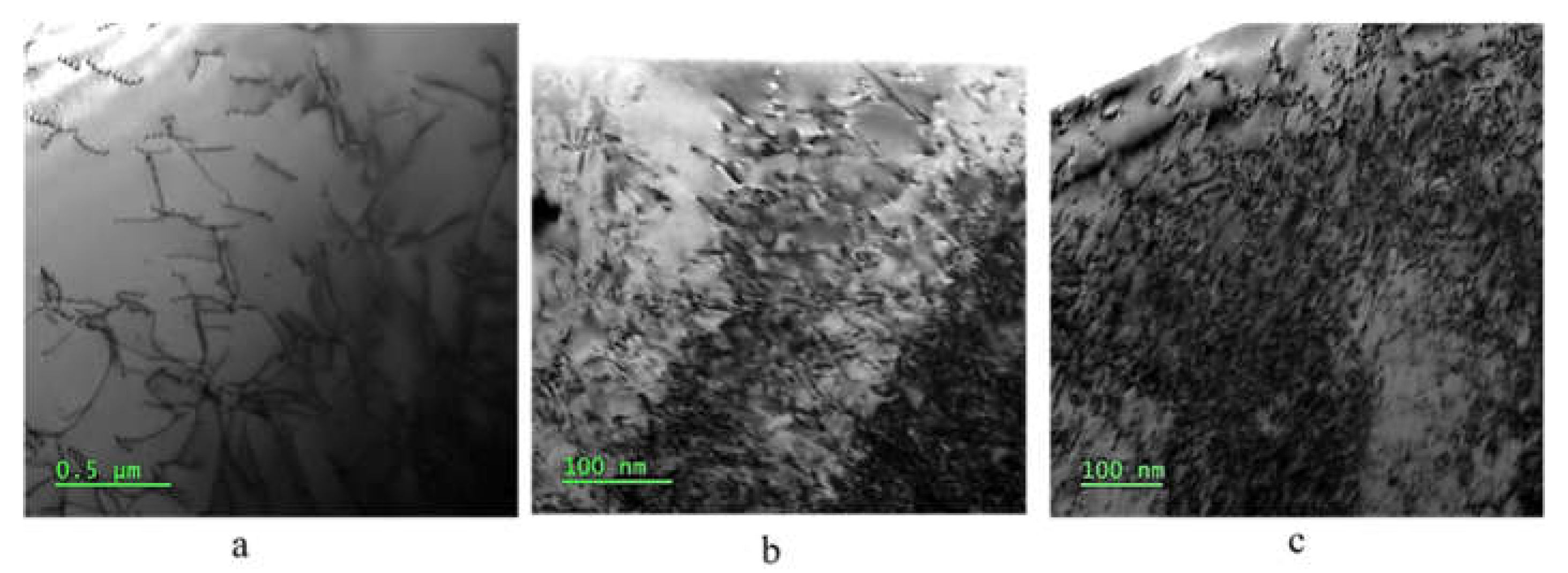

Figure 6 illustrates dislocations in the three samples. There are some dislocations in the annealed sample, and the dislocation density is considerably increased by the ECAP, which is decreased by the subsequent recovery treatment.

Table 2 provides dislocations density for the three samples. As shown, the dislocation density increases by two orders of magnitude after the ECAP process, and it is decreased to half by the subsequent recovery treatment.

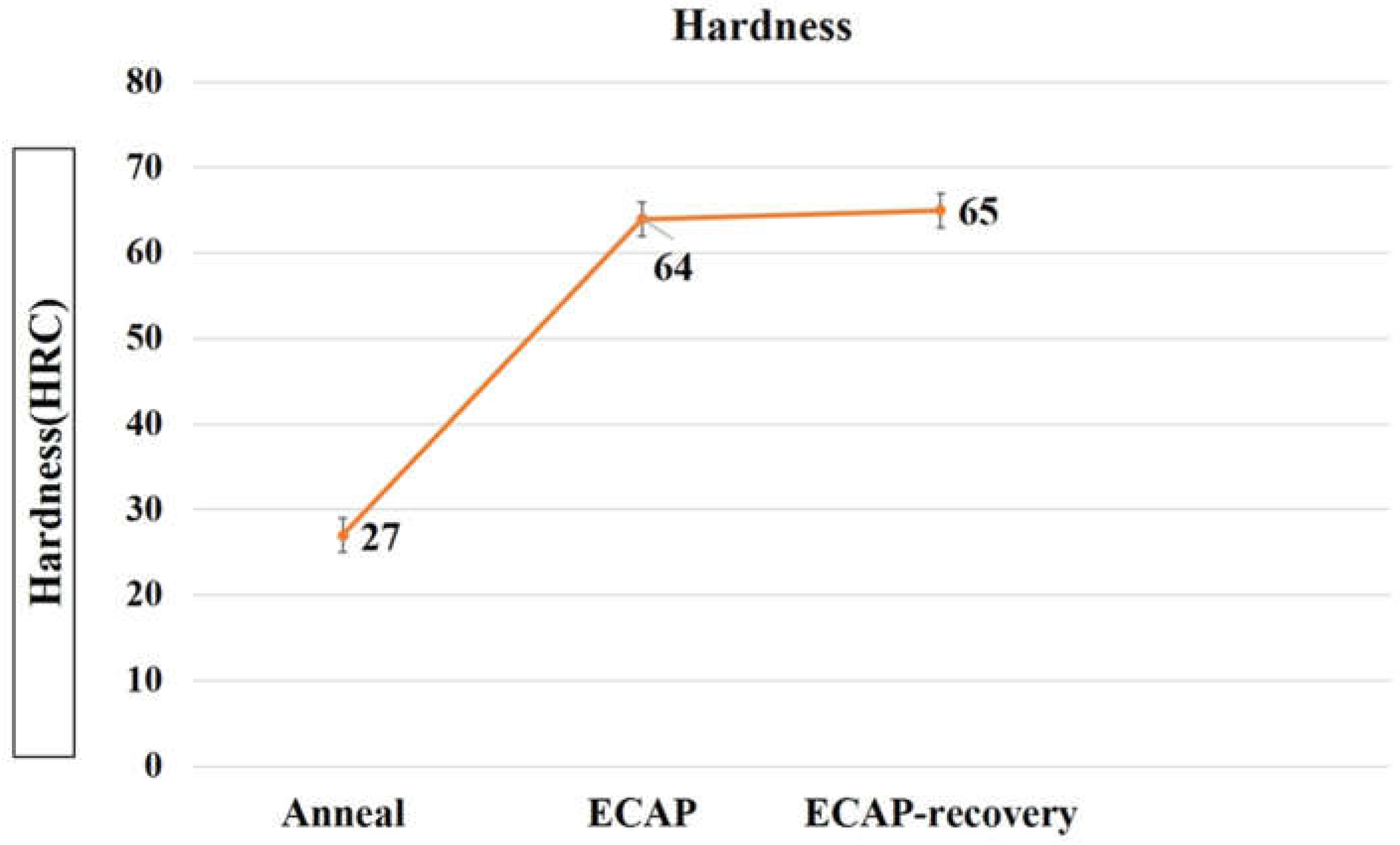

The increase in dislocation density results in an enhanced strain-hardening effect. The hardness of the samples was measured, shown in

Figure 7. As demonstrated, the hardness increases from 27.5 to 64.5(2.34 times) after the ECAP process, and the subsequent recovery treatment further increases it slightly from 64.5 to 65.5. Such a slight increase in hardness, even if the dislocation density decreases as shown in

Table 2, implies that the recovery treatment renders the defect configurations more stable or raises the barriers to defects’ generation and movement.

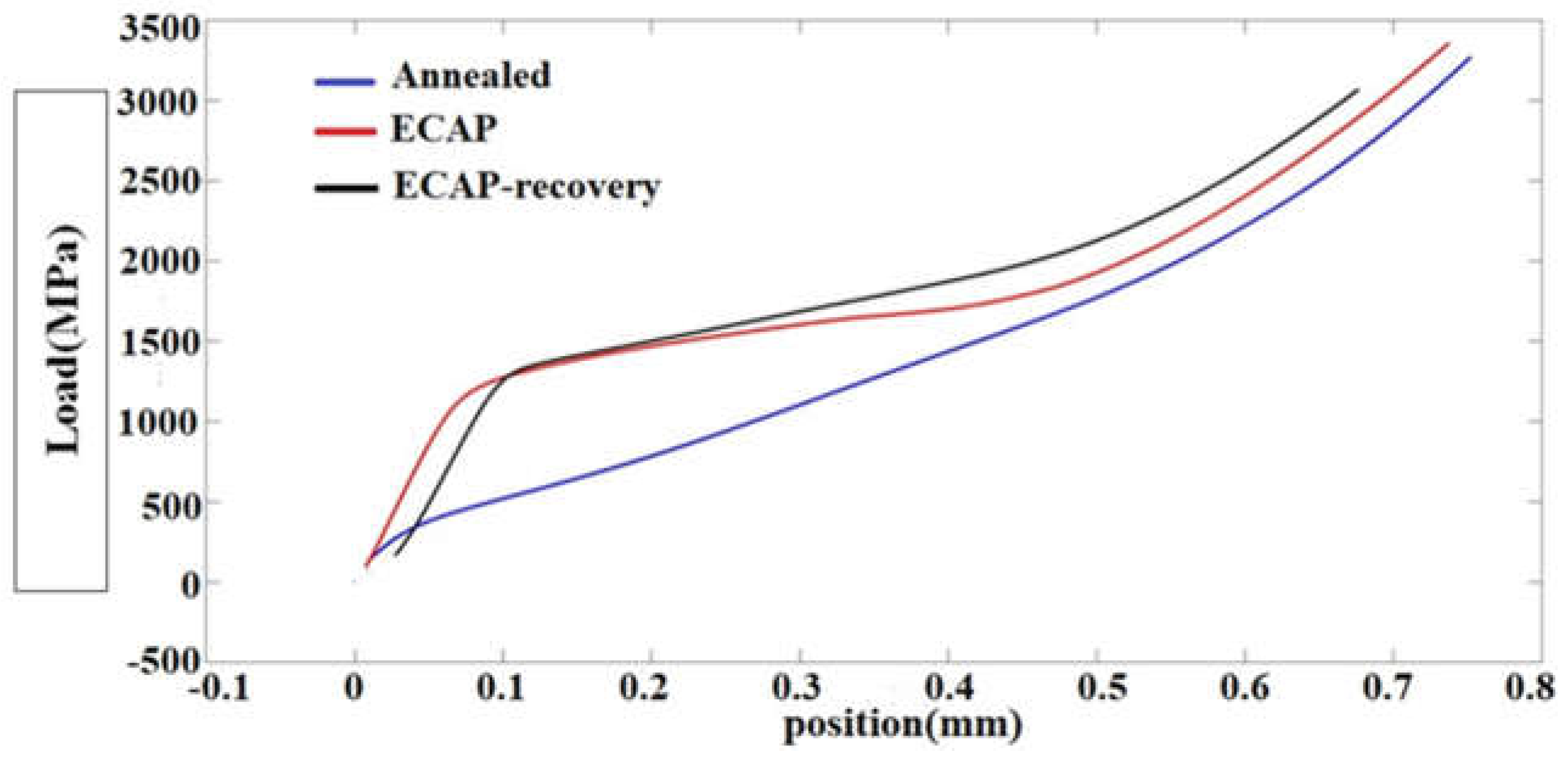

For more information on the influences of ECAP and the recovery treatment on mechanical behavior, compressive tests were performed.

Figure 8 displays stress-strain curves obtained from the compressive tests. None of the samples failed under compressive force up to 40 KN due to the high formability of 316L steel.

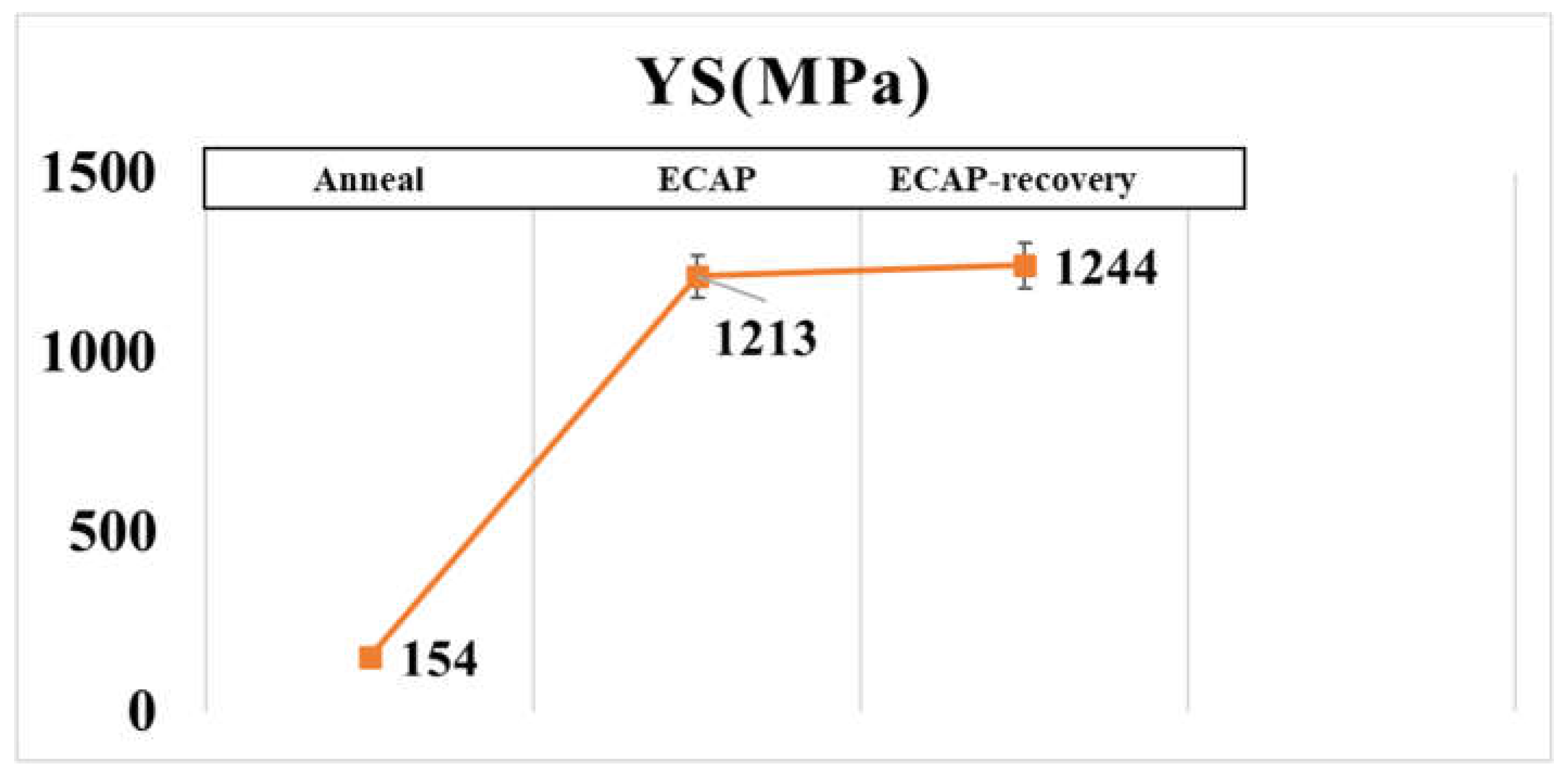

According to the compressive tests, the ECAP increases the yield stress from 154MPa to 1213MPa (nearly 8 times), which further increases to 1244 MPa by the recovery process. The variations in the yield strength are consistent with the hardness values of the three samples.

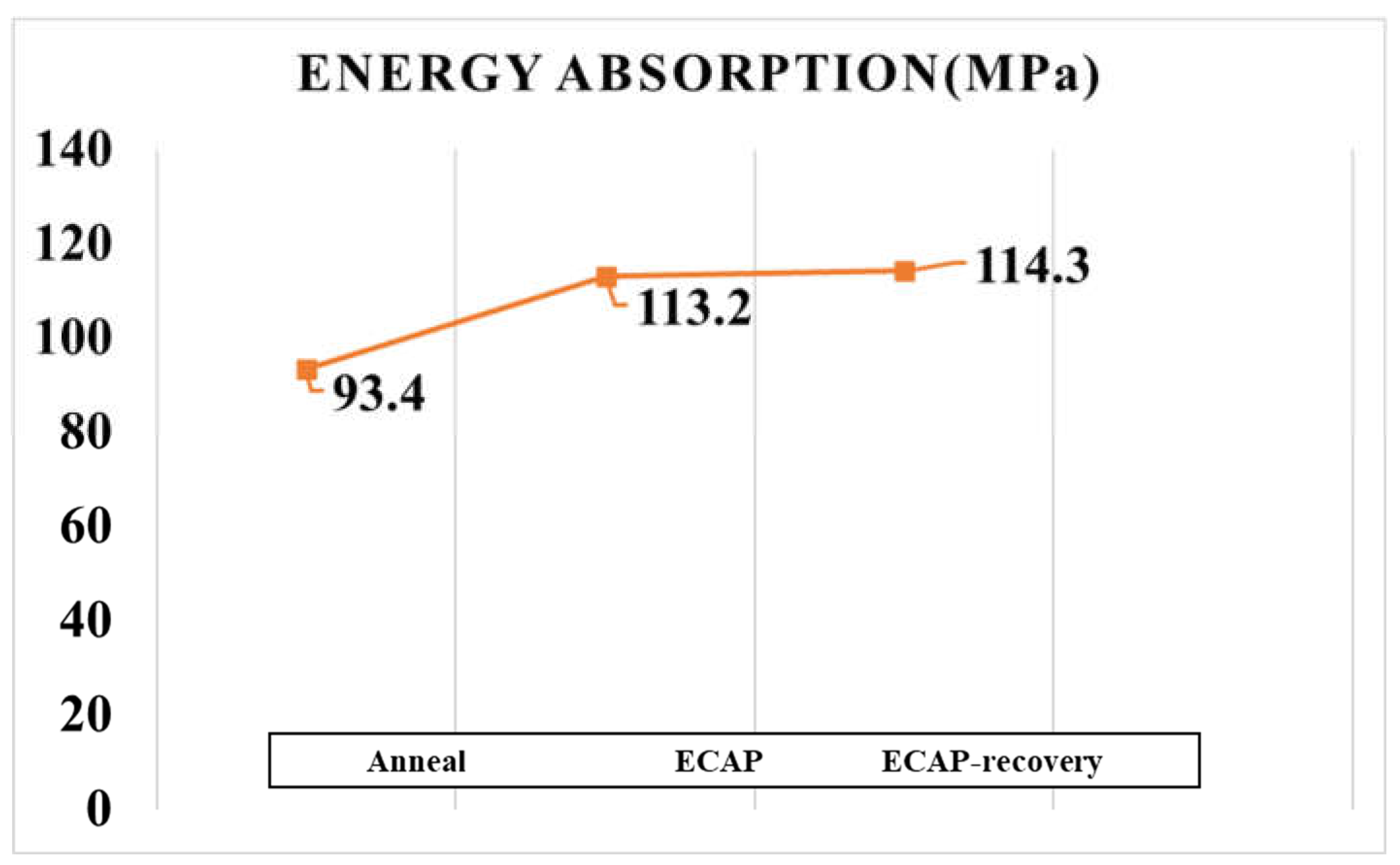

For wear resistance, the energy absorption ability is beneficial, since it helps dissipate deformation energy and reduce the damage to the crystal lattice. In this study, the energy absorption up to the strain of 70% was determined from the compressive stress-strain curves for 316L in different states. As shown in

Figure 10, the energy absorption increases from 93.4MPa to 113.2MPa after the ECAP process, and it increases a little more after the subsequent recovery treatment.

The XRD patterns of the samples in the three states are displayed in

Figure 11, with a focus on the 2θ range of 36-56°. As shown, the three samples have similar XRD patterns, characterized by two main peaks of γ phase, meaning that the ECAP and ECAP-recovery processes did not change the structure of the steel, except by introducing dislocations and deformation twinning.

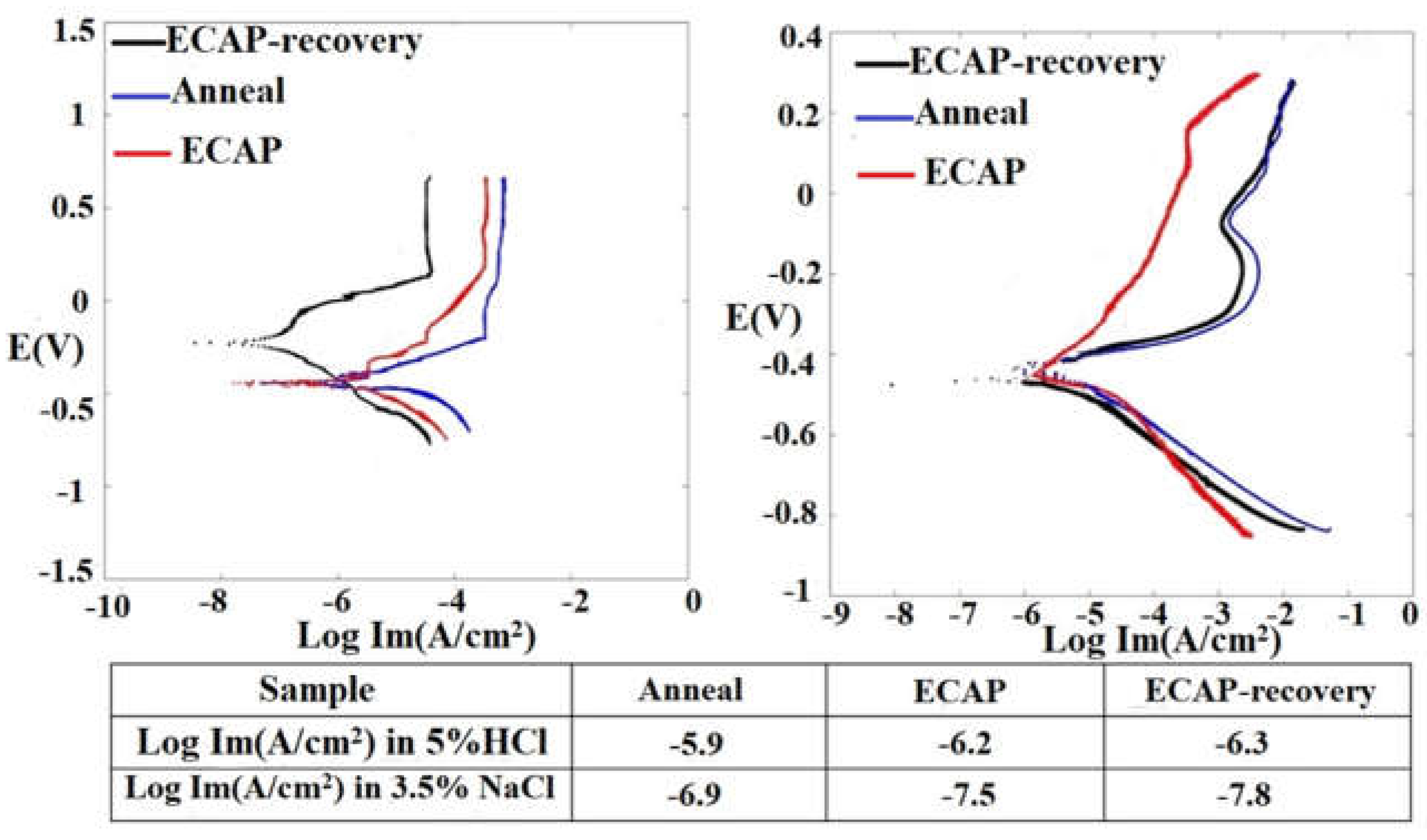

Effects of ECAP and ECAP-recovery treatments on the corrosion behavior of the steel were investigated. Potentiodynamic polarization curves of the three samples in 3.5%NaCl and 5%HCl solutions, respectively, were obtained.

Figure 12 illustrates the polarization curves of the 316L alloy in three states: annealed, ECAP-treated, and ECAP-recovery-treated. In the 3.5%NaCl solution, the annealed and ECAP-treated samples show similar corrosion potentials while the subsequent recovery treatment markedly increases the corrosion potential or the susceptibility to corrosion. In the acidic solution, the corrosion potentials of the three samples are similar. However, the ECAP and ECAP-recovery treatments decrease the corrosion rates in both solutions (see values given in the table in

Figure 12). It is clear that the recovery treatment helps improve the corrosion resistance, since it may reduce the strain energy, rendering the material closer to a more stable state, and improve the adherence of surface film to the substrate through reducing the interfacial defects.

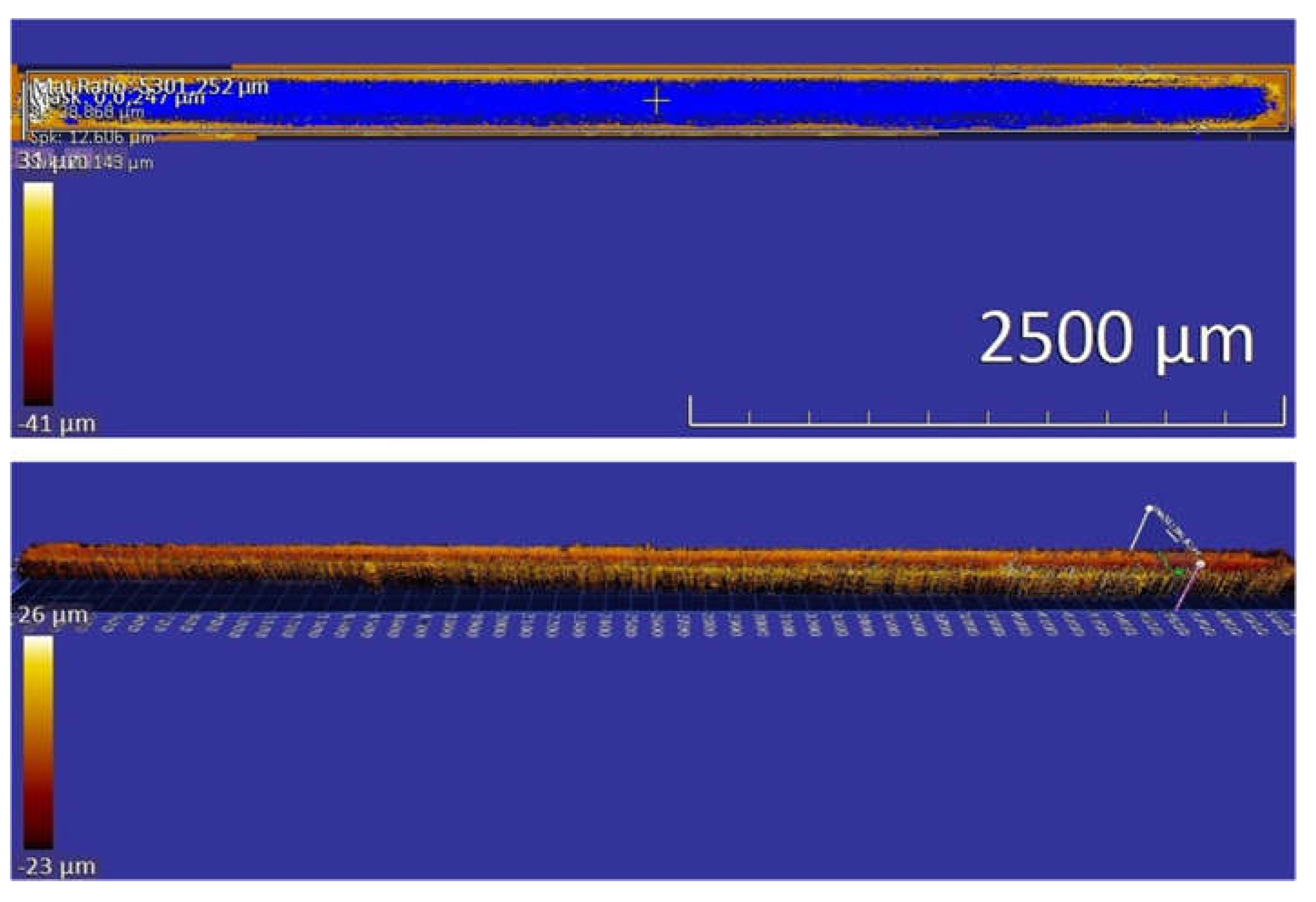

In this study, scratching wear tests were performed for the three samples. The wear resistance of the samples was evaluated by measuring the volume loss caused by reciprocal scratching with a diamond tip over a certain time.

Figure 13 illustrates a sample scratching track, whose dimensions were measured using a profilometer. As shown in

Table 3, the measured volume losses caused by reciprocal scratching under 10 N indicate that the wear resistance of the annealed sample is slightly higher than that of the sample that experienced the ECAP treatment, but the subsequent recovery treatment noticeably enhances the wear resistance. However, under 20 N (see

Table 4) the ECAP sample performed better than the annealed one. Again, the recovery treatment considerably improves the wear behavior under the larger load. The ECAP-recovery sample shows the highest wear resistance under different loads.

The resistances of the steel in the three states to corrosive wear were also evaluated respectively in 3.5%NaCl and 5% HCl solutions under a load of 5N, results of which are shown in

Table 5. As shown, the volume loss caused by corrosive wear decreases by the ECAP, and the ECAP-recovery results in the lowest volume loss.

4. Discussion

As shown earlier, the annealed sample has an average grain diameter equal to 28.7μm, which is decreased to 17.7μm by the ECAP, and then is slightly increased to 19.87μm by subsequent recovery treatment. This is understandable since severe plastic deformation can squeeze grains and generate dislocations cells, leading to reduced average grain size. When the recovery treatment is applied, dislocations may be locally rearranged, slightly increasing the grain size and turning the dislocation cells into nano-grains. According to the Hall-Petch relationship, the smaller grain size increases the hardness of the material. Besides, the increased dislocation density promotes strain-hardening, making important contributions to the hardness of the material. Furthermore, the ECAP-induced deformation twinning may interact with dislocations, thus further enhancing the strain-hardening effect. The high ductility of UFG 316LN austenitic stainless steel was due to twinning, while in commercial steel, strain-induced ά-martensite contributed to high ductility [

20]. The above-mentioned factors are responsible for the increases in mechanical strength. As shown, the hardness of the steel increases by 2.34 times after the ECAP process, and it doesn’t change much after the recovery process. During the compressive tests, none of the samples failed under the load up to 40 N. The compressive yield strength increases by 7.8 times after the ECAP process, and it doesn’t change noticeably after the recovery treatment. Energy absorption increases after the ECAP process and it increases slightly after the recovery treatment. For UFG metallic materials processed by severe plastic deformation techniques, the annihilation of mobile dislocations and the clustering of the remaining dislocations into low-angle grain boundaries during annealing can yield hardening. It is also shown that plastic deformation after annealing can cause a restoration of the yield strength and hardness to the same level as observed before annealing. The possible reasons for this deformation-induced softening effect are discussed in detail [

34].

The corrosion resistance of the steel is improved by ECAP in both solutions (see

Figure 12). The reason could be mainly ascribed to the fact that the grain refinement promotes Cr diffusion along the grain boundaries, thus accelerating passivation and the formation of passive film. The subsequent recovery treatment increases the benefits by reducing the SPD-induced disordering and turning dislocation cells into nano-grains, thus enhancing the adherence of passive film to the substrate [

26].

The wear test results show that the wear resistance of the steel is not affected much by ECAP under 10 N but the benefit of ECAP on the wear resistance shows up under a larger contact load of 20 N. The beneficial effect of ECAP on the wear resistance becoming pronounced under larger loads is understandable, since as the wear attack becomes more severe, the mechanical strength raised by ECAP may render its benefits to the wear resistance more standing out. The higher mechanical strength reduces the contact area and the depth of asperity penetration, and thus plowing and delamination processes. As for the subsequent recovery treatment, its benefits to the wear resistance are constantly obvious, since it decreases the stress concentrations and favors the toughness. As a result, a combination of hardness and toughness always helps reduce wear, no matter whether the wearing force is large or small.

It is noticed that under a further smaller load of 5 N, the ECAP sample shows a larger volume loss, compared to the annealed one (see

Table 5). This could be related to a kind of surface singularity. In the bulk material, dislocations can mutually interact, e.g., pinning and tangling each other, leading to strain-hardening and enhanced wear resistance. However, if the wearing force is small, the deformation occurs only is a shallow surface layer. Such mutual interaction of dislocations and other lattice defects could be largely weakened since dislocations and defects are relatively free to move to the surface, bear in mind that the surface loses the constraint from the other half the lattice. As a result, atoms on the surface could be readily removed layer by layer, especially when the surface has a higher degree of disordering or with more accumulated dislocations or defects. In corrosive environments, such damage could be enlarged as shown in

Table 5. On the surface, electron localization and stability are different from those inside the bulk, thus influencing the surface's mechanical and electrochemical behaviors. Such singularity of physical surfaces is certainly worth further investigation. The subsequent recovery treatment can reduce the disordering and enhance the adherence of the passive film to the substrate as well as the surface singularity, leading to a higher resistance to both dry wear and wear in the corrosive solutions regardless of the contact force, as observed in the present study (

Table 5). This study demonstrates the necessity of recovery treatment after ECAP for improving the mechanical, tribological, and electrochemical properties of 316L steel, which is also applicable to other passive alloys.

Wear resistance is influenced by multiple factors, e.g., microstructure and properties of materials, the type and magnitude of contact force, mechanical action, environmental corrosivity, temperature, and their synergy [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Thus, tailoring microstructure using various approaches, e.g., ECAP, heat treatments, texture control, phase transformations, surface microstructure control, loading conditions, etc. [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50], is the primary task of materials engineering.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the effects of equal channel angular pressing (ECAP) and subsequent recovery treatment on microstructure, mechanical, tribological, and corrosion properties of 316L steel were investigated. The following conclusions are drawn:

The ECAP increased the dislocation density by 2 orders of magnitude and introduced considerable deformation twinning, leading to an increase in the compressive yield strength of the steel by about 8 times. The subsequent recovery treatment slightly increased the yield strength. Corresponding hardness was increased by more than two-fold.

The ECAP and ECAP-recovery improved the ability of energy absorption by about 23% at a compressive strain of 70%, which helped enhance the steel’s resistance to wear attacks.

The ECAP process improved the corrosion behavior. The subsequent recovery treatment markedly increased the corrosion resistance due to lowered dislocation density or strain energy and improved adherence of surface film to the substrate by reducing the interfacial defects.

The ECAP was beneficial to the wear resistance of the steel but not under low loads. The benefit became pronounced as the contact load increased. However, ECAP-recovery always markedly enhanced the wear resistance regardless of the contact load. ECAP-recovery also markedly enhanced the corrosive wear resistance of the steel.

The recovery treatment is essential to reduce the degree of disordering and stress concentrations caused by ECAP, which is effective in improving the mechanical properties and elevating resistances of 316L steel to wear, corrosion, and corrosive wear.

Author Contributions

Methodology, A.R.; investigation, A.R., A.H. and G.D.; data curation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; writing—review and editing, A.R., M.K. and D.L.; supervision, M.K. and D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rostami M, Miresmaeili R, Heydari Astaraee A. Investigation of surface nanostructuring, mechanical performance and deformation mechanisms of AISI 316L stainless steel treated by surface mechanical impact treatment. Metals and Materials International. 2023 Apr;29(4):948-67. [CrossRef]

- Kunčická L, Kocich R, Pagáč M. Experimental and Numerical Study of Behavior of Additively Manufactured 316L Steel Under Challenging Conditions. Metals. 2025 Feb 8;15(2):169. [CrossRef]

- Hanawa T, Hiromoto S, Yamamoto A, Kuroda D, Asami K. XPS characterization of the surface oxide film of 316L stainless steel samples that were located in quasi-biological environments. Materials transactions. 2002;43(12):3088-92. [CrossRef]

- Hermawan H, Ramdan D, Djuansjah JR. Metals for biomedical applications. Biomedical engineering-from theory to applications. 2011 Aug 29;1:411-30.

- Fathi MH, Salehi MA, Saatchi A, Mortazavi V, Moosavi SB. In vitro corrosion behavior of bioceramic, metallic, and bioceramic–metallic coated stainless steel dental implants. Dental materials. 2003 May 1;19(3):188-98.

- Li JS, Gao WD, Cao Y, Huang ZW, Gao B, Mao QZ, Li YS. Microstructures and mechanical properties of a gradient nanostructured 316L stainless steel processed by rotationally accelerated shot peening. Advanced Engineering Materials. 2018 Oct;20(10):1800402. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.N., Wei, F.A., La, P.Q. and Ma, F.L., 2018. Enhanced mechanical properties of 316L stainless steel prepared by aluminothermic reaction subjected to multiple warm rolling. Metals and Materials International, 24, pp.633-643. [CrossRef]

- Naghizadeh M, Mirzadeh H. Microstructural evolutions during reversion annealing of cold-rolled AISI 316 austenitic stainless steel. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 2018 Jun;49:2248-56. [CrossRef]

- Biesiekierski A, Wang J, Gepreel MA, Wen C. A new look at biomedical Ti-based shape memory alloys. Acta biomaterialia. 2012 May 1;8(5):1661-9. [CrossRef]

- Williams DF. Titanium as a metal for implantation. Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology. 1977 Jan 1;1(4):202-.

- Langdon, T.G., 2013. Twenty-five years of ultrafine-grained materials: Achieving exceptional properties through grain refinement. Acta Materialia, 61(19), pp.7035-7059. [CrossRef]

- Gebril MA, Omar MZ, Mohamed IF, Othman NK, Aziz AM, Irfan OM. The Microstructural Refinement of the A356 Alloy Using Semi-Solid and Severe Plastic-Deformation Processing. Metals. 2023 Nov 2;13(11):1843. [CrossRef]

- Shin DH, Kim WJ, Choo WY. Grain refinement of a commercial 0.15% C steel by equal-channel angular pressing. Scripta Materialia. 1999 Jul 9;41(3):259-62.

- Sheremetyev V, Derkach M, Churakova A, Komissarov A, Gunderov D, Raab G, Cheverikin V, Prokoshkin S, Brailovski V. Microstructure, mechanical and superelastic properties of Ti-Zr-Nb alloy for biomedical application subjected to equal channel angular pressing and annealing. Metals. 2022 Oct 5;12(10):1672. [CrossRef]

- Baysal, E., Koçar, O., Kocaman, E. and Köklü, U., 2022. An overview of deformation path shapes on equal channel angular pressing. Metals, 12(11), p.1800. [CrossRef]

- Valiev RZ, Estrin Y, Horita Z, Langdon TG, Zehetbauer MJ, Zhu Y. Producing bulk ultrafine-grained materials by severe plastic deformation: ten years later. Jom. 2016 Apr;68:1216-26. [CrossRef]

- Roodposhti PS, Farahbakhsh N, Sarkar A, MURTY KL. Microstructural approach to equal channel angular processing of commercially pure titanium—A review. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China. 2015 May 1;25(5):1353-66. [CrossRef]

- Sheremetyev V, Derkach M, Churakova A, Komissarov A, Gunderov D, Raab G, Cheverikin V, Prokoshkin S, Brailovski V. Microstructure, mechanical and superelastic properties of Ti-Zr-Nb alloy for biomedical application subjected to equal channel angular pressing and annealing. Metals. 2022 Oct 5;12(10):1672. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Dong H, Huang H, Yuan T, Bai J, Jiang J, Fang F, Ma A. Enhanced Strengthening and Toughening of T6-Treated 7046 Aluminum Alloy through Severe Plastic Deformation. Metals. 2024 Sep 24;14(10):10939. [CrossRef]

- Xu DM, Li GQ, Wan XL, Xiong RL, Xu G, Wu KM, Somani MC, Misra RD. Deformation behavior of high yield strength–high ductility ultrafine-grained 316LN austenitic stainless steel. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2017 Mar 14;688:407-15. [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, K. and Kurzydlowski, K.J., 2024. The Effect ECAP Processing Routes on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AISI 316 Austenitic Stainless Steel. Physics of Metals and Metallography, pp.1-8. [CrossRef]

- Vacchi GD, Magalhães DC, Kugelmeier CL, Silva RD, Mendes Filho AD, Kliauga AM, Rovere CA. Influence of Long-Term Immersion Tests on the Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior of an Ultrafine-Grained Aluminum Alloy. Metals. 2024 Dec 11;14(12):1417. [CrossRef]

- Awang Sh’ri DN, Zahari ZS, Yamamoto A. Effect of ECAP Die Angle on Mechanical Properties and Biocompatibility of SS316L. Metals. 2021 Sep 24;11(10):1513. [CrossRef]

- Fu X, Ji Y, Cheng X, Dong C, Fan Y, Li X. Effect of grain size and its uniformity on corrosion resistance of rolled 316L stainless steel by EBSD and TEM. Materials Today Communications. 2020 Dec 1;25:101429. [CrossRef]

- Xin SS, Xu J, Lang FJ, Li MC. Effect of temperature and grain size on the corrosion behavior of 316L stainless steel in seawater. Advanced Materials Research. 2011 Sep 10;299:175-8. [CrossRef]

- Ralston, K.D. and Birbilis, N., 2010. Effect of grain size on corrosion: a review. Corrosion, 66(7), pp.075005-075005. [CrossRef]

- Wang XY, Li DY. Mechanical, electrochemical and tribological properties of nano-crystalline surface of 304 stainless steel. Wear. 2003 Aug 1;255(7-12):836-45. [CrossRef]

- Gao N, Wang CT, Wood RJ, Langdon TG. Tribological properties of ultrafine-grained materials processed by severe plastic deformation. Journal of Materials Science. 2012 Jun;47:4779-97. [CrossRef]

- Stolyarov VV, Shuster LS, Migranov MS, Valiev RZ, Zhu YT. Reduction of friction coefficient of ultrafine-grained CP titanium. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2004 Apr 25;371(1-2):313-7.

- Cheng X, Li Z, Xiang G. Dry sliding wear behavior of TiNi alloy processed by equal channel angular extrusion. Materials & design. 2007 Jan 1;28(7):2218-23. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S., Seok Yu, H. and Hyuk Shin, D., 2009. Low sliding-wear resistance of ultrafine-grained Al alloys and steel having undergone severe plastic deformation. International journal of materials research, 100(6), pp.871-874. [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, M., Kumar, D.R., Suresh, K.S. and Neelakantan, S., 2023. Effect of equal channel angular pressing on the microstructure and tribocorrosion characteristics of 316L stainless steel. Vacuum, 210, p.111908. [CrossRef]

- Herliansyah MK, Dewo P, Soesatyo MH, Siswomihardjo W. The effect of annealing temperature on the physical and mechanical properties of stainless steel 316L for stent application. In2015 4th International Conference on Instrumentation, Communications, Information Technology, and Biomedical Engineering (ICICI-BME) 2015 Nov 2 (pp. 22-26). IEEE.

- Gubicza, J., 2020. Annealing-induced hardening in ultrafine-grained and nanocrystalline materials. Advanced Engineering Materials, 22(1), p.1900507.

- Wang XY, Li DY. Application of an electrochemical scratch technique to evaluate contributions of mechanical and electrochemical attacks to corrosive wear of materials. Wear. 2005 Jul 1;259(7-12):1490-6. [CrossRef]

- Akonko S, Li DY, Ziomek-Moroz M. Effects of cathodic protection on corrosive wear of 304 stainless steel. Tribology Letters. 2005 Mar;18:405-10. [CrossRef]

- Hutchings I, Shipway P. Tribology: friction and wear of engineering materials. Butterworth-heinemann; 2017 Apr 13.

- Tong X, Zhang H, Li DY. Effect of annealing treatment on mechanical properties of nanocrystalline α-iron: an atomistic study. Scientific reports. 2015 Feb 13;5(1):8459. [CrossRef]

- Budinski KG, Steven T, Budinski T. properties and selection for friction, wear, and erosion applications, 2021. ASM International, Materials Park, OH, USA.

- Yin S, Li DY. Effects of prior cold work on corrosion and corrosive wear of copper in HNO3 and NaCl solutions. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2005 Mar 15;394(1-2):266-76. [CrossRef]

- Bunge HJ. Texture analysis in materials science: mathematical methods. Elsevier; 2013 Sep 3.

- Peng H, Chen DL, Bai XF, Wang PQ, Li DY, Jiang XQ. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-to-Al dissimilar welded joints with an Ag interlayer using ultrasonic spot welding. Journal of Magnesium and Alloys. 2020 Jun 1;8(2):552-63. [CrossRef]

- Ocelík V, Janssen N, Smith SN, De Hosson JT. Additive manufacturing of high-entropy alloys by laser processing. Jom. 2016 Jul;68:1810-8. [CrossRef]

- Ron T, Shirizly A, Aghion E. Additive manufacturing technologies of high entropy alloys (HEA): Review and prospects. Materials. 2023 Mar 19;16(6):2454. [CrossRef]

- Li DY, Elalem K, Anderson MJ, Chiovelli S. A microscale dynamical model for wear simulation. Wear. 1999 Apr 1;225:380-6. [CrossRef]

- Faghihi S, Li D, Szpunar JA. Tribocorrosion behaviour of nanostructured titanium substrates processed by high-pressuretorsion. Nanotechnology. 2010 Nov 10;21(48):485703.

- He ZF, Jia N, Wang HW, Liu YJ, Li DY, Shen YF. The effect of strain rate on mechanical properties and microstructure of a metastable FeMnCoCr high entropy alloy. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2020 Mar 3;776:138982. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Chen J, Lin Y, Xue Z, Roven HJ, Skaret PC. Microstructure, mechanical properties and wear resistance of an Al–Mg–Si alloy produced by equal channel angular pressing. Progress in Natural Science: Materials International. 2020 Aug 1;30(4):485-93.

- Wang CT, Gao N, Wood RJ, Langdon TG. Wear behavior of an aluminum alloy processed by equal-channel angular pressing. Journal of Materials Science. 2011 Jan;46:123-30. [CrossRef]

- Zeng S, Li J, Zhou N, Zhang J, Yu A, He H. Improving the wear resistance of PTFE-based friction material used in ultrasonic motors by laser surface texturing. Tribology international. 2020 Jan 1;141:105910. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The ECAP die (left image) and samples after two ECAP processes (right side).

Figure 1.

The ECAP die (left image) and samples after two ECAP processes (right side).

Figure 2.

Optical microscope images of samples a) annealed, b) after the ECAP, and c) after the ECAP-recovery treatment.

Figure 2.

Optical microscope images of samples a) annealed, b) after the ECAP, and c) after the ECAP-recovery treatment.

Figure 3.

Grain sizes of the three samples.

Figure 3.

Grain sizes of the three samples.

Figure 4.

TEM image results for three samples a) Annealed b) ECAP 3) ECAP-recovery.

Figure 4.

TEM image results for three samples a) Annealed b) ECAP 3) ECAP-recovery.

Figure 5.

TEM images of ECAP and ECAP-recovery samples. Twins can be seen clearly. (a and c) ECAP and ECAP-recovery samples, respectively; (b & d) - selected area electron diffraction patterns for the ECAP and ECAP-recovery samples, respectively.

Figure 5.

TEM images of ECAP and ECAP-recovery samples. Twins can be seen clearly. (a and c) ECAP and ECAP-recovery samples, respectively; (b & d) - selected area electron diffraction patterns for the ECAP and ECAP-recovery samples, respectively.

Figure 6.

Dislocations in the three samples: a) annealed, b) ECAP, and c) ECAP-recovery.

Figure 6.

Dislocations in the three samples: a) annealed, b) ECAP, and c) ECAP-recovery.

Figure 7.

Hardness results under a load of 100 g.

Figure 7.

Hardness results under a load of 100 g.

Figure 8.

Compressive stress-strain curves of the three samples.

Figure 8.

Compressive stress-strain curves of the three samples.

Figure 9.

Compressive yield strengths of the three samples.

Figure 9.

Compressive yield strengths of the three samples.

Figure 10.

Energy absorption values of the three samples, determined from the compressive stress-strain curves up to the strain of 70% (

Figure 7).

Figure 10.

Energy absorption values of the three samples, determined from the compressive stress-strain curves up to the strain of 70% (

Figure 7).

Figure 11.

XRD patterns of 316L steel samples in three states.

Figure 11.

XRD patterns of 316L steel samples in three states.

Figure 12.

Dynamic polarization curves of samples in the three states, determined in 3.5%NaCl (left) and 5%HCl (right) Solutions, and obtained Im values. The ECAP-recovery sample performed the best in both solutions.

Figure 12.

Dynamic polarization curves of samples in the three states, determined in 3.5%NaCl (left) and 5%HCl (right) Solutions, and obtained Im values. The ECAP-recovery sample performed the best in both solutions.

Figure 13.

Example of measuring volume loss (up image) and max depth with profilometer machine.

Figure 13.

Example of measuring volume loss (up image) and max depth with profilometer machine.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of 316L.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of 316L.

| Element |

Fe |

Cr |

Ni |

Mn |

C |

Mo |

Si |

| Present (Wt.%) |

Bal |

18.2 |

12.1 |

1.9 |

0.03 |

2.3 |

1 |

Table 2.

Dislocation densities in three samples.

Table 2.

Dislocation densities in three samples.

| Sample |

Annealed |

ECAP |

ECAP-recovery |

| Present (Wt.%) |

3.08x109 cm-2

|

3.23x1011 cm-2

|

1.29x1011 cm-2

|

Table 3.

Scratch test result under 10 N.

Table 3.

Scratch test result under 10 N.

| Sample |

Anneal |

ECAP |

ECAP-recovery |

| Max depth (μm) |

23.8 ± 1 |

21 ± 1 |

16.4 ± 1 |

| Volume loss (μm3)e6 |

9.8 ± 1 |

10.6 ± 1 |

6.8 ± 1 |

Table 4.

Scratch test result under 20 N.

Table 4.

Scratch test result under 20 N.

| Sample |

Anneal |

ECAP |

ECAP-recovery |

| Max depth (μm) |

49 ± 2 |

30 ± 1 |

24 ± 1 |

| Volume loss (μm3)e6 |

31 ± 1 |

27.5 ± 1 |

12 ± 1 |

Table 5.

Volume loss (μm3)e6 for corrosive wear test under 5N load in different corrosion environment.

Table 5.

Volume loss (μm3)e6 for corrosive wear test under 5N load in different corrosion environment.

| Sample |

Anneal |

ECAP |

ECAP-recovery |

| Dry wear |

1 |

1.6 |

0.6 |

| 3.5%NaCl |

0.37 |

0.8 |

0.32 |

| 5% HCl |

1.6 |

2.7 |

1.2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).