Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Proposed Theoretical Framework

3. Discussion

4. The New Algorithm for Entanglement Swapping

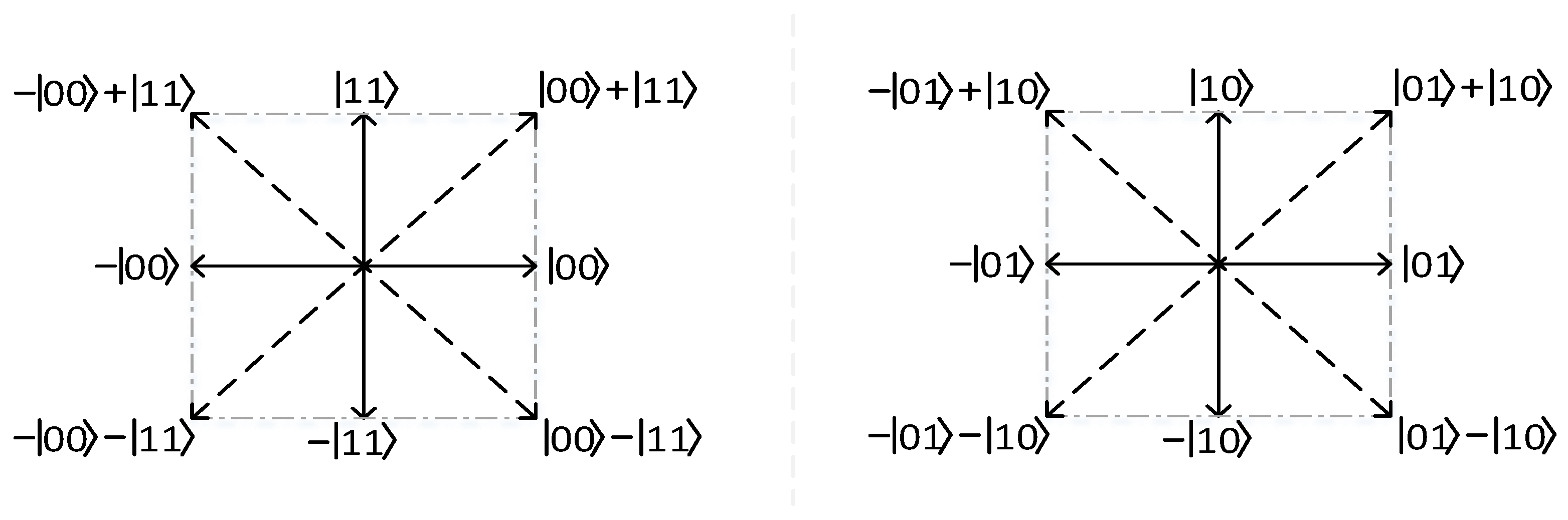

4.1. Entanglement Swapping Between Two Bell States

4.2. The Proposed Algorithm

5. Conclusion

References

- Nielsen, M. A., Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Schro¨dinger, E. (1935). Die gegenwa¨rtige Situation in der Quantenmechanik. Naturwissenschaften, 23(50), 844-849.

- Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M., Horodecki, K. (2007). Quantum entanglement. Review of Modern Physics, 81(2), 865-942. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z. X., Fan, P. R., Zhang, H. G. (2022). Entanglement swapping for Bell states and Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger states in qubit systems. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 585, 126400. [CrossRef]

- Zukowski, M., Zeilinger, A., Horne, M. A., et al. “Event-ready-detectors” Bell experiment via entanglement swapping. Physical Review Letters, 1993, 71(26), 4287. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. G., Ji, Z. X., Wang, H. Z., et al. (2019). Survey on quantum information security. China Communications, 16(10), 1-36. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z. X., Fan, P. R., Zhang, H. G. (2020) Security proof of qudit-system-based quantum cryptography against entanglement-measurement attack. arXiv preprint, arXiv: 2012.14275. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. S. (1964). On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. Physics Physique Fizika, 1(3), 195.

- Halliday, D., Resnick, R., Walker, J. Fundamentals of Physics[M]. Wiley, 2013.

- Zeng, S. Q., Liu, J. Z. The I Ching is really easy. Shaanxi Normal University Press, 2009.

- Bennett, C. H., Brassard, G., Crépeau, C., et al. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. Physical review letters, 1993, 70(13): 1895. [CrossRef]

- Bose, S., Vedral, V., Knight, P. L. (1998). Multiparticle generalization of entanglement swapping. Physical Review A, 57(2), 822. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, L., Song, D. D. (2000). Entanglement swapping chains for general pure states. Physical Review A, 62(5), 052315. [CrossRef]

- Bouda, J., Buzˇek, V. (2001). Entanglement swapping between multi-qudit systems. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General, 34(20), 4301-4311. [CrossRef]

- Karimipour, V., Bahraminasab, A., Bagherinezhad, S. (2002). Entanglement swapping of generalized cat states and secret sharing. Physical Review A, 65(4). [CrossRef]

- Sen, A., Sen, U., Brukner, Cˇ., Buzˇek, V., Z˙ukowski, M. (2005). Entanglement swapping of noisy states: A kind of superadditivity in nonclassicality. Physical Review A, 72(4), 042310. [CrossRef]

- Roa, L., Mun˜oz, A., Gru˜ning, G. (2014). Entanglement swapping for X states demands threshold values. Physical Review A, 89(6), 064301. [CrossRef]

- Kirby, B. T., Santra, S., Malinovsky, V. S., Brodsky, M. (2016). Entanglement swapping of two arbitrarily degraded entangled states. Physical Review A, 94(1), 012336. [CrossRef]

- Bergou, J. A., Fields, D., Hillery, M., Santra, S., Malinovsky, V. S. (2021). Average concurrence and entanglement swapping. Physical Review A, 104(2), 022425. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z. X., Fan, P. R., Zhang, H. G. (2020). Entanglement swapping theory and beyond. arXiv preprint, arXiv: 2009.02555. [CrossRef]

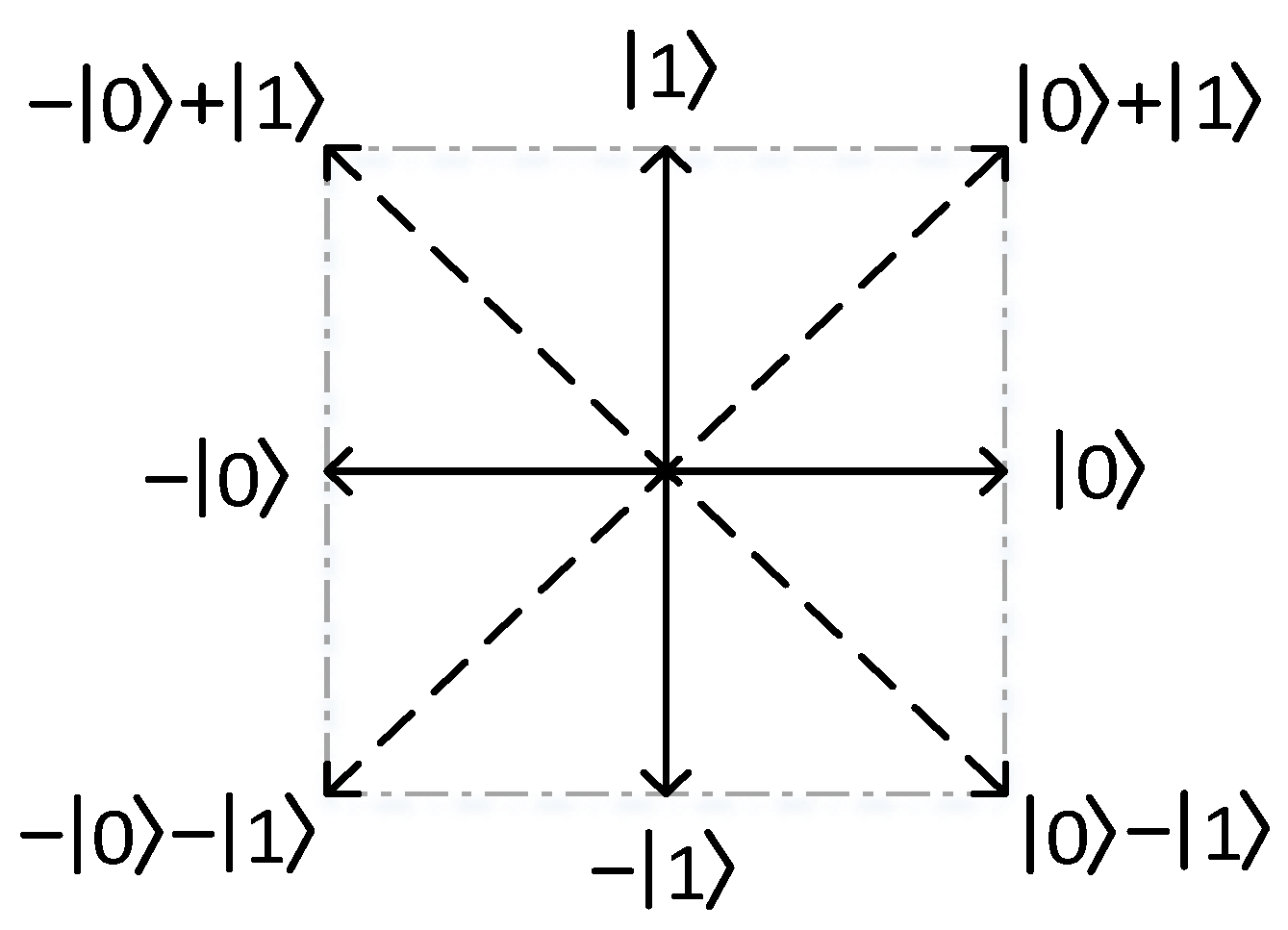

| Joint state | Combinations of the states of two subsystems |

|---|---|

| ➀ or | |

| ➁ or | |

| ➂ or | |

| ➃ or |

| (a) | (b) | ||||

| (c) | (d) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).