1. Introduction

Understanding the connections and distinctions between classical and quantum systems is a fundamental challenge in physics [

1]. In classical mechanics, interactions occur between distinguishable entities, whereas quantum mechanics introduces coherence and entanglement, leading to systems that behave as a single, inseparable unit composed of indistinguishable components.

Quantum coherence and entanglement manifest in various systems, from singlet states in helium atoms to Cooper pairs in superconductors [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. These quantum phenomena challenge classical intuition, motivating further investigation into entanglement and its potential Realizations beyond quantum mechanics.

To illustrate the characteristics of entanglement, consider a unified system composed of entangled particles within the framework of the no-cloning theorem. In this theory, codes encoded in spatially separated entangled particles cannot be duplicated, as an eavesdropper attempting to copy the code locally lacks access to the full information encoded across the distant entangled counterparts [

7,

8].

Interestingly, we are familiar with an entangled state in classical mechanics [

9,

10]. Specifically, the center-of-mass (COM) system represents a collective state in which all constituent particles behave as a unified entity. This raises a fundamental question: what is the significance of the corresponding orthogonal states?

To address this, we revisit classical mechanics and we find that to restore classical laws, non-Hermitian operators are required. This, provides a perspective that sheds light on this question and the broader relationship between classical and quantum descriptions.

"Newton’s laws laid the foundation for classical mechanics, introducing the fundamental concepts of force and momentum. Over time, more elegant formulations, such as the principle of least action, emerged, describing mechanics without explicitly invoking force. However, since our approach aligns closely with the theory of measurement in quantum mechanics, we reintroduce the concept of force as it remains a directly measurable quantity."

2. Abstract Operator Form

In the following, we reformulate established concepts using terminology aligned with our approach.

The Abstract Operator Form (A.O.F.) expresses operators in their most fundamental form, independent of specific representations. It serves as a formal introduction without additional details.

We define the force and momentum operators in A.O.F. as:

Since an observer may not be familiar with A.O.F., they describe these operators using familiar concepts, such as spatial behavior. In quantum mechanics, this corresponds to expressing operators in a particular basis, a process we call Realization.

Here, we realize force and momentum operators via particle representations using Fock space. While quantum mechanics inherently represents measurable quantities through A.O.F., classical operators may deviate from this structure.

3. Realization

By Realization, we refer to the mathematical concept of projection. Abstract quantities like momentum and force acquire physical relevance through projection. For example, projecting the force operator onto a spatial basis defines its distribution, while a particle basis reveals its interactions. Similarly, projecting momentum aligns it with individual particles.

These Realizations provide distinct interpretations of force and momentum, linking them to classical motion through the chosen basis.

3.1. Momentum Realization in Distinguishable Particles

Momentum manifests in space through entities such as particles or light. In radiation, momentum arises from electromagnetic waves transferring energy or exerting force. In classical mechanics of particles, it represents particle inertia.

For a system of distinguishable particles labeled by

j, the states are described as

, where

. In this representation, the momentum operator takes the form:

where

represents the operator elements and the subscript

specifies the distinguishable-particles representation; however, for brevity, we omit this notation in subsequent expressions after sub

Section 3.2.

Since classical mechanics does not define an intrinsic "momentum of interaction between particles," we assume a diagonal momentum operator in the particle basis:

where

denotes the classical momentum of the

j-th particle.

3.2. Force in Distinguishable Particles Realization

We implement similar procedure to obtain:

Considering an interacting particles, we a consider a non-diagonal force operator. Thus,

If we follow quantum formalism, we should have accepting hermit operator, meaning that

. This contradict the classical mechanics laws

. Thus we consider new approach:

3.3. Realized Momentum and Force Operators in Second Quantization

In a Fock space, and are the creation and annihilation operators of the j -particles satisfying the relations: , and , with the states product . In our model we assume a Fermions-like states: .

In that formulation eqs.

2 and

3 become:

4. Classical Fundamental Equation

In the following, we extend the force operator introduced in Eq.

1 to forms that represent both interaction and the grouping of elements into systems. The fundamental equation to be defined remains valid across all force representations.

Following the principles of classical mechanics, we introduce the fundamental operator equation:

This equality holds under the following conditions:

When both sides of the equation share the same eigenstates, the equation reduces to:

where

and

are the corresponding eigenvalues, interpreted as the classical force and momentum variables, respectively. In other words, an observer can equate both sides of Eq.

6 only when using the same terminology or representation.

When the operators possess different eigenstates, the equation is evaluated by comparing only their matrix elements. Specifically, in our case, we compare the diagonal elements.

5. Building Classical Mechanics of Interacting Particles

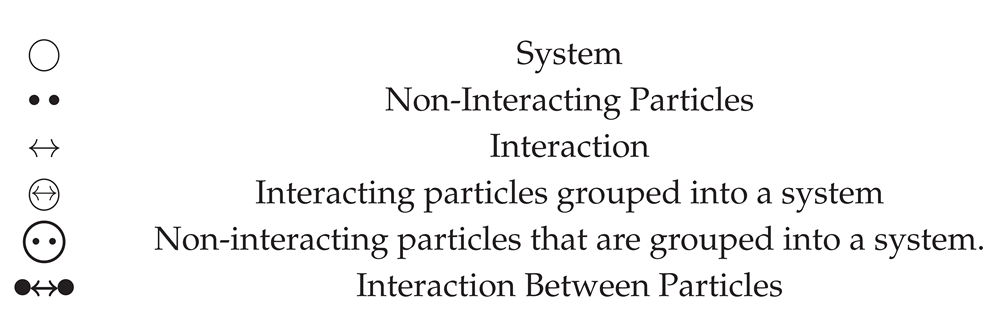

5.1. Symbolic Representation

5.2. Non-Interacting Particles-Single Particle Basis

We begin with operators describing non-interacting particles. Introducing the classical items interaction and system of particles definition, will be introduced in the following subsections.

The force and momentum operators describing non-interacting particles are:

with the common distinguishable particles

N states:

Eq,

6 yields the classical equation:

6. An Operator Framework for Grouping Particles into a System

Grouping particles into a system corresponds to a loss of information concerning each individual particle. To formalize this, we implement the

erasure operator or

trace operation which is usually used in quantum information theory to "erases" the specific state information of a system by projecting it onto a maximally mixed state or a specific basis state, thereby removing distinguishable information [

11,

12]. Although we explore classical mechanics rather than quantum mechanics, the same idea is implacable.

Thus, we define the system operators:

Eq.

6 yields the classical equation for a system of particles:

7. Interaction

Nilpotent operators play a crucial role in mathematical physics, particularly in the representation of interaction terms [

13,

14,

15,

16]. An operator

is nilpotent if:

A fundamental property of nilpotent operators is that their only eigenvalue is zero, imposing structural constraints on interactions.

We define the interaction force operator

as nilpotent. For

, it takes the form:

where

represents the classical interaction force.

In the standard basis:

where

and

, the force operator simplifies to:

Since this matrix has only zero eigenvalues, retains its nilpotent nature, confirming its role in interaction dynamics.

For

N particles, using Jordan formalism [

17], we generalize:

Defining the center-of-mass state as:

we obtain:

which is consistent with the absence of external forces in the center-of-mass frame.

8. Various Scenarios of Interacting Particles

We introduced three types of force operators:

for isolated particles (Eq. 9),

for particles recognized as a system (Eq.

11), and the interaction force

(Eq.

16). By appropriately selecting the proper operators` combination, various scenarios emerge that effectively restore the classical mechanics framework.

8.1. Interacting Particles in View of Separated Particles

Introducing interaction to a system of particles is obtained by adding the non-interacting particles with the iteration operator. that is:

Consider a two observed particles,labeled by

and

, representing a pair of particles, out of the whole ensemble. We define their states by

and

. In matrix representation we have:

The solitary particles representation guides us to represent the momentum operator with eq.

8. That is, diagonal under the single particles states. In contrast to the momentum representation, the off-diagonal terms in

causes the

,

-states to no longer be eigenstates of

. Therefore, if the observer insists on measuring the forces acting between the

-

-particles he obtain the following:

This result verifies our formalism, as it naturally adheres to Newton’s third law of interaction where the notations

represent all observed pairs in the system.

The fundamental equation then satisfies and

8.2. Center of Mass System

The center of mass system treats all particles as a unit, with momentum and force operators given in Eqs.

11. For non-interacting particles, the fundamental equation holds:

For interacting particles, the force operator is:

leading to

The center of mass state,

, is an eigenstate of

with eigenvalue

, representing the classical external force.

Adding the interaction nilpotent operator makes the system force operator non-Hermitian. Thus, the center of mass vector, while an eigenstate, provides no information on other orthogonal states.

From Eqs.

11,

is also an eigenstate of momentum, yielding:

Thus, our operator formalism recovers classical mechanics.

9. Entanglement of Particles` Relative Coordinates

A key classical quantity is the relative coordinate

, corresponding to the state

. In matrix form:

The nilpotent matrix

satisfies

.

10. Summary

This work reformulates classical mechanics using an operator-based framework, representing momentum and force through fundamental operators. We introduce their Realization in particle systems and incorporate interactions via nilpotent operators, ensuring they do not alter fundamental properties. Applying the trace operation, we extend force and momentum from individual particles to a system-level, recovering classical mechanics.

The center-of-mass vector, treated as a classical entangled state, suggests that unmeasured orthogonal states should have meaning, though non-Hermitian interactions prevent their physical realization. We propose that the classical-quantum distinction originates in the nature of interactions.

11. Discussion and Future Directions

This study reveals that features commonly associated with quantum mechanics, such as entanglement, also emerge in classical mechanics. The center-of-mass system and relative coordinate frame exhibit entanglement-like properties, yet the non-Hermitian nature of classical operators challenges the development of a complete theoretical framework. The lack of a rigorous classical coherence model further complicates the understanding of measurement-induced collapse.

Despite this, classical entangled states—such as the center of mass—persist over large separations. Natural systems tend toward less-detailed states, making the center of mass the probable configuration. However, perception imposes a localized view, resembling a classical analog of quantum collapse. While our framework does not define a coherence violation mechanism, it conceptually illustrates this transition.

Since stringent conditions are required for quantum behavior, most phenomena—including in biology—are fundamentally non-quantum. A classical collapse perspective, exemplified by stem cell differentiation (see Supplementary Information), could expand theoretical frameworks beyond conventional physics.

Future work could refine the momentum operator by incorporating a vector potential, enabling a radiative formulation within the classical framework:

This extension may offer new insights into classical coherence and its relation to radiation phenomena.

Supplementary Materials

Pluripotent stem cells have the potential to develop into nearly any cell type. Before differentiation, they can be considered “entangled” in the sense that they exist in an undetermined state, with no inherent distinction between the potential lineages. Upon differentiation, the identity of each cell is established, analogous to a collapse process. For example, bipotent stem cells can differentiate into two specific lineages—such as hepatoblasts forming hepatocytes or cholangiocytes [

18,

19]—mirroring the classical entanglement discussed in this study. This perspective suggests that classical collapse concepts may provide a foundation for developing a theoretical framework to describe differentiation dynamics.

Author Contributions

Yehuda Roth conceived the research, developed the theoretical framework, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during this study.

AI Assistance

Artificial Intelligence was used to assist in refining the language, structuring the manuscript, and formatting the LaTeX document. All conceptual and analytical work was performed by the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carcassi, G.; Aidala, C.A. The fundamental connections between classical Hamiltonian mechanics, quantum mechanics and information entropy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.07206, arXiv:2001.07206 2020.

- Pachucki, K. α4 Ry corrections to singlet states of helium. Physical Review A 2006, 74, 022512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.F.; Zhang, G.M. Phase Coherence of Pairs of Cooper Pairs as Quasi-Long-Range Order of Half-Vortex Pairs in a Two-Dimensional Bilayer System. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 195301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronzani, A.; Altimiras, C.; D’Ambrosio, S.; Virtanen, P.; Giazotto, F. Phase-driven collapse of the Cooper condensate in a nanosized superconductor. Physical Review B 2016, 94, 214506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.X.; et al. Cooper pairing and phase coherence in iron superconductor Fe1+x(Te,Se). Nature Physics 2015, 11, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ramakrishnan, T.V.; Dasgupta, C. Pairing fluctuations determine low energy electronic spectra in cuprate superconductors. Physical Review B 2011, 83, 024510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootters, W.K.; Zurek, W.H. A Single Quantum Cannot be Cloned. Nature 1982, 299, 802–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieks, D. Communication by EPR devices. Physics Letters A 1982, 92, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Y. Type II entanglement in classical mechanics. Results in Physics 2021, 24, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Y. Superposition and second quantization in classical mechanics. Results in Physics 2019, 14, 102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plenio, M.; Vitelli, V. The physics of forgetting: Landauer’s erasure principle and information theory. Contemporary Physics 2001, 42, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.Y. Measurement, Trace, Information Erasure and Entropy. arXiv preprint quant-ph/0307026.

- Kato, T. Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kugo, T.; Ojima, I. Covariant Operator Formalism of Gauge Theories and Quantum Gravity. Progress of Theoretical Physics 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Dynamical Breaking of Supersymmetry. Nuclear Physics B 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalin, I.A.; Vilkovisky, G.A. Gauge Algebra and Quantization. Physics Letters B 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrimmon, K. A Taste of Jordan Algebras; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oertel, M.; Shafritz, S. Isolation and characterization of a murine resident liver stem cell. Nature 2006, 439, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.O. Directed differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into functional cholangiocyte-like cells. Nature Protocols 2017, 12, 2266–2274. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).