1. Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AlloHSCT) is one of the possible, and in some cases the only effective approach to the treatment of malignant diseases of the blood system and genetic nonmalignant diseases of the blood system and depressions of hematopoiesis [

1,

2,

3]. Primary bone marrow (BM,) BM primed with G-CSF, mobilized HSCs or umbilical cord blood are used as sources of transplant for alloHSCT [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The principal difference of using primary or G-CSF-primed BM is that such a transplant contains a mixture of cells of different nature: HSCs, MSCs and various subpopulations of stromal progenitor cells, as well as different kinds of mature cells [

8,

9]. When mobilized HSCs and cord blood are used, a CD34

+ sorted cell subpopulation, which is thought to be virtually free of MSCs and other stromal cells, is usually used [

10]. Although some subpopulations of MSCs might express CD34 [

11,

12,

13,

14]. In contrast, the use of whole BM as a transplant has the potential to transfer not only hematopoiesis but also BM stroma because it contains MSCs.

The relevance of BM stroma transplantation is high and is supported by several reasons. Firstly, the graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in alloHSCT, among other organs and tissues, develops in the BM, and its targets in it are osteoblast niches of HSCs [

15]. Secondly, graft hypofunction sometimes takes place after alloHSCT, which is accompanied by significant abnormalities in BM stromal cells [

16,

17]. Thirdly, the cytostatic effects of induction and consolidation chemotherapy before alloHSCT damage the cells of the recipient's BM stroma, which may cause inefficient hematopoiesis or delayed renewal of bone, fat and cartilage tissue in recipients [

18,

19,

20]. Another reason to replace BM stroma in a patient with malignant disease of the blood system is established remodeling of the recipient's stroma by tumor cells [

20,

21]. A specific microenvironment (leukemic niche) can be created in the modified stroma, which protects tumor cells, including leukemic stem cells (LSCs), from apoptosis when exposed to cytostatics. It is also exposed to cytostatics and supports tumor cell proliferation, sometimes to the detriment of maintaining normal hematopoiesis [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], which drives relapse of the disease [

20,

26]. In this study, we decided to test hypotheses that may contribute to the emergence of effective methods of stromal transplantation. Our assumption was that the main function of stem cells in the adult organism is physiological tissue renewal and regeneration in case of injury or suppression of function.

We hypothesized that the failure of most studies published on this topic [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] was due to the fact that MSCs administered intravenously during allogeneic BM transplantation (alloBMT) enter an organism in which the BM stroma is largely preserved, which prevents them from functioning as stem cells. If this is the case, then preliminary damage to the recipient's BM stroma should stimulate MSCs to divide and differentiate in order to replenish the impaired function. Our assumption was reinforced by a study that showed that preliminary irradiation of a recipient may lead to efficient homing of MSCs to the BM [

31]. Here we used a genetic approach to establish a solid basement of the observed phenomenon and pave the way to successful BM stroma transplantation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Mice of inbred strain B10 of both sexes aged 20-21 weeks (females) and 17-18 weeks (males) were used in this study. All animals received food and water ad libitum and were kept under conventional conditions at 12 h of daylight. All studies with animals were conducted in accordance with the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experiments and Other Scientific Purposes. The study was approved by the local ethical committee, protocol № 183 from 12.12.2024.

2.2. Irradiation

Females from the experimental groups were subjected to total body irradiation (TBI) on the BioBeam 8000 unit using cesium-137 gamma radiation once with an intensity of 21.8 cGy/min. One group of mice was irradiated at a dose of 6.5 Gy (n = 5) and the second group was irradiated at a dose of 13 Gy (n = 5). Control animals were also irradiated in the same way at the same facility at a dose of 6.5 Gy (n = 6) and 13 Gy (n = 6).

2.3. Isolation of BM Cells and Intravenous Injection

On the day of irradiation, all animals (females) from the experimental groups (unirradiated, irradiated with 6.5 Gy and irradiated with 13 Gy) were injected with a suspension of BM cells from males of the same strain. The cells were injected intravenously into the tail vein in a volume of 0.5 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA). BM extracted from the femoral bones and tibia of donors was used for injection. Donor mice were sacrificed by cervical vertebral dislocation. The femurs and tibia of both hind limbs were obtained, and the epiphyses were cut off, leaving only the diaphyses. A 2 ml syringe with a G21 or G23 needle filled with 1 ml of PBS was inserted into the bone cavity. A stream of PBS was used to wash out the BM into a 2 ml polypropylene tube. BM fragments were turned into a single-cell suspension by repeatedly passing through the needle of the same syringe. The concentration of cells in the obtained suspension was calculated having stained the cells with gentian violet prepared with acetic acid for lysis of erythrocytes. The suspension was adjusted to the required concentration using PBS, drawn into a syringe and injected into the tail vein of female mice.

2.4. CFU-F

The detailed methodology of CFU-F seeding and harvest is presented in the

Supplementary materials. Briefly, 30 days after irradiation, femoral bone diaphyses were obtained from recipient mice and medullary cylinders were isolated in sterile conditions. BM cells were placed 3 x 10

6 cells per T25 flask containing 5 ml of complete αMEM medium (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with 20% fetal calf serum (FBS) (FBS Xtra, Collected in South America) (Capricorn Scientific, Ebsdorfergrund, Germany) and 5 ng/ml FGF2. After 3 weeks, one of the flasks was stained with crystal violet to count CFU-F colonies. The cells in the remaining flasks were used for sorting of stromal cells.

2.5. Cell Sorting

Cells were counted, washed from media and stained with a monoclonal antibody to CD45-APC (clone 30-F11) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and 7-AAD (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). CD45

– and CD45

+ cell subpopulations were sorted using a flow cell sorter (BD FACSAria III Cell Sorter, USA). Fixation-free cells stained with antibodies were sorted in Purity mode directly into lysis buffer (DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kits for DNA isolation, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A schematic of gating and a typical sample are shown in

Supplementary materials, Fig. S10.

2.6. DNA Isolation

DNA from sorted CD45

– cells was isolated on the same day using HiPure Blood DNA Mini Kit (Magen Biotechnology Guangzhou, China). Obtained DNA was used to measure donor chimerism by digital droplet PCR (ddPCR). In addition, femoral and tibial bone diaphyses were obtained from each mouse. They were carefully cleaned externally of muscle tissue and internally of marrow remnants by repeatedly passing at least 10 ml of PBS through the tubular bone cavity. The bones were immediately frozen at -70°C and stored frozen until DNA isolation. DNA was isolated from each individual femur or tibia. Bone meal was obtained by grinding the bone in a ceramic mortar filled with liquid nitrogen with addition of 0.5 mL 0.5M EDTA immediately after the nitrogen had evaporated. DNA was extracted from the obtained bone meal using a previously described method [

27]. The concentration of isolated DNA was measured on a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer using the dsDNA Quantitation, High Sensitivity kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.7. Digital Droplet PCR

DNA isolated from sorted CD45– cells was used to determine donor chimerism (proportion of donor cells) using SniperDQ24 digital droplet PCR (Sniper Medical Technology, Suzhou, China). Primers and probes for Prssly and Gapdh genes were added to the prepared PCR mastermix and diluted to the desired volume. The PCR mixture was added to 8-well strips provided by the manufacturer and DNA from one of the experimental samples or control DNA was added to each well of the strip. Control DNA included female and male DNA. Female DNA (XX genotype) served as a positive control for all ddPCR steps and, simultaneously, as a negative control for donor cells carrying the Y chromosome. Male DNA (XY genotype) served as a positive control for ddPCR and a positive control for donor cell content. No template control (NTC) was also included in the panel of controls.

2.8. Real-Time PCR

Donor chimerism in DNA isolated from bones was determined by real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) using a calibration curve (detailed methodology of its construction is described in

Supplementary materials). Briefly, to construct the calibration curve, concentration-aligned DNA solutions of XX and XY genotypes were used to obtain calibration samples in which the proportion of male DNA varied from 100% to 0.0003% in steps of 2. These samples were used for multiplex RQ-PCR in a BioRad CFX Connect amplifier. In each sample, signal from

Prssly and

Gapdh targets was simultaneously detected. The resulting threshold cycle values Cq(Prssly) and Cq(Gapdh) were used to calculate the threshold cycle difference ΔCq = Cq(Prssly) - Cq(Gapdh) (see

Supplementary materials, Table 2). RQ-PCR with DNA isolated from the tested biological samples was performed under the same conditions as for the calibration curve (PCR parameters - see

Supplementary material, Table 3). The 2

ΔCq values of the tested samples were substituted into the equation of the calibration curve and donor chimerism values were calculated using the trend line equation (see

Supplementary materials, Fig. S7).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The samples of the experimental groups were examined for normality using Kruskal-Wallis test. If the samples passed the normality test, the presence of statistical differences on the compared parameter was made using Student's criterion, taking a statistically reliable difference at p < 0.05. If the groups didn’t meet the criterion of normality on the tested parameter, the comparison was made using nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. In some cases, the samples were checked for Log-normality and, if it was present, the values of the logarithm of the tested parameter were compared by Student's criterion.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Design

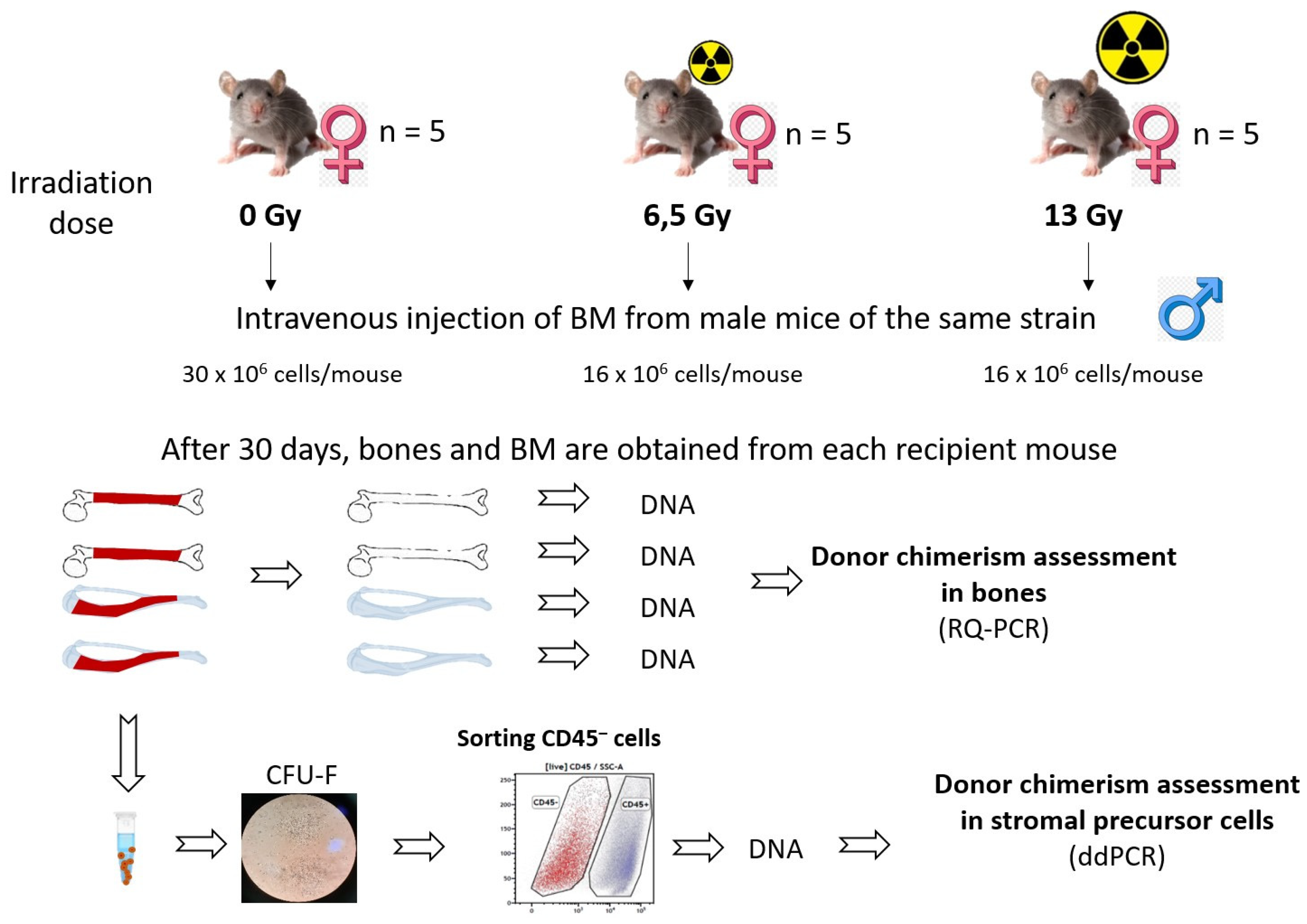

The main experimental groups and experimental procedures are shown in

Figure 1.

There were 3 experimental groups of female mice: unirradiated (n = 5), irradiated at a dose of 6.5 Gy (n = 5), irradiated at a dose of 13 Gy (n = 5). Each female from the experimental groups was injected on the day of irradiation with a suspension of BM cells from male mice of the same strain and age (unirradiated group - on the day the other groups were irradiated). There were also unirradiated (n = 6, 3 males, 3 females) and irradiated with the same doses of 6.5 Gy (n = 6) and 13 Gy (n = 6, all females) mice of the same strain and age that were not reconstituted by donor BM. One month later, the mice in the experimental groups and the unirradiated control group were sacrificed, and BM was taken from the femurs and the femurs themselves. Three weeks after seeding, some flasks containing CFU-Fs were stained with crystal violet for colony counting. The remaining flasks were used to sort the CD45

– subpopulation of stromal cells on a cell sorter. DNA was extracted from the CD45

–cell fraction and donor chimerism (proportion of donor cells to total cells) was assessed by ddPCR. Bones were isolated from each recipient mouse and each bone (two femurs and two tibias, a total of four bones from each mouse) independently. Femur and tibia bones were carefully cleaned of associated muscle tissue and residual BM, and DNA was extracted from the bones. Donor chimerism was assessed in the bones using RQ-PCR (a detailed description of the method used to construct the calibration curve and determine donor chimerism is provided in the

Supplementary Material). Survival analysis showed that irradiation at a dose of 13 Gy is lethal if the recipient's hematopoiesis is not restored by donor BM: all 6 mice irradiated at this dose and not injected with BM died within 15 days after irradiation (

Supplementary materials, Fig. S8). Of the 5 mice irradiated at 13 Gy that were reconstituted by donor BM, three mice survived. The death of two mice in this group may be related to the effects of radiation exposure on other tissues or to technical difficulties in intravenous injection of BM (failure to enter a vein). In the other groups, no deaths were recorded within 30 days after irradiation.

Analysis of CFU-Fs concentration showed no statistically significant differences between groups (

Supplementary Material, Fig. S9), although there was a trend towards lower CFU-Fs concentration in the BM of 13 Gy irradiated recipient mice. The median CFU-Fs concentration was 21 CFU-Fs/10

6 BM cells (range 17 - 35.7) in the unirradiated group, 28.6 CFU-Fs/10

6 BM cells (range 27.3 - 29.8, n = 2) in the group of 6.5 Gy irradiated mice, and 9.0 CFU-Fs/10

6 BM cells (range 9 - 26.7, n = 3) in the group of 13 Gy irradiated animals. The lack of differences may be due to the small sample size. On the other hand, it may be due to the fact that the injected donor BM stromal cells to some extent restored the content of CFU-Fs in the recipient BM. In the group of non-irradiated animals, the concentration was within the range of normal values established for mice [

28].

Cells from flasks containing CFU-Fs were trypsinized, washed from medium and serum and stained with antibodies against CD45. The stained cells were characterised by high viability by staining for 7-AAD (>99%) and clear separation of CD45

– and CD45

+ cells. Analysis showed that only a small proportion of cells in the flasks were CD45

– cells: their proportion averaged 8.8% ± 1.4% for all groups (no statistically significant difference between groups according to Kruskal-Wallis test), the remaining cells in the vials were CD45

+ haematopoietic cells (

Supplementary Material, Table 5). The CD45

– subpopulation of cells was sorted (

Supplementary Material, Fig. S10), and DNA was isolated from them to measure donor chimerism.

3.2. Selection of Targets for the Assessment of Donor Chimerism

Donor chimerism was measured using PCR-based genetic approaches. Two targets were selected in the mouse genome, one on an autosome and another on Y chromosome. The first target is the

Gapdh gene located on mouse chromosome 6. The primers and probe were selected to target only the

Gapdh gene and not its pseudogenes (see

Supplementary Material, section Assessing the specificity of primers and probes used to determine donor chimerism). Thus, there were only 2 primer and probe landing sites in each genome (one on each of the homologous chromosomes). The second target is the

Prssly gene located on the mouse Y chromosome. The peculiarity of this gene is that it has no homologues on the X chromosome. Another feature of the

Prssly gene is that it is estimated to be represented by a single copy, whereas most genes on the Y chromosome are multi-copy genes [

29]. It was shown recently that

Prssly has two pseudogenes on the Y chromosome [

29,

30]. For this target we selected primers and a hydrolysable probe labelled at the 5‘-end with FAM fluorophore and a fluorescence quencher at the 3’-end (see

Supplementary materials, Table 1), which had two landing sites - directly on the Prssly gene and on one of its pseudogenes (see

Supplementary materials, Figures S3-S5). Thus, both probes had two landing sites in the mouse genome, which caused the same increase in fluorescence in PCR reactions (see

Supplementary materials, Fig. S6).

3.3. Donor Chimerism in Bone Marrow and Bones of Recipients

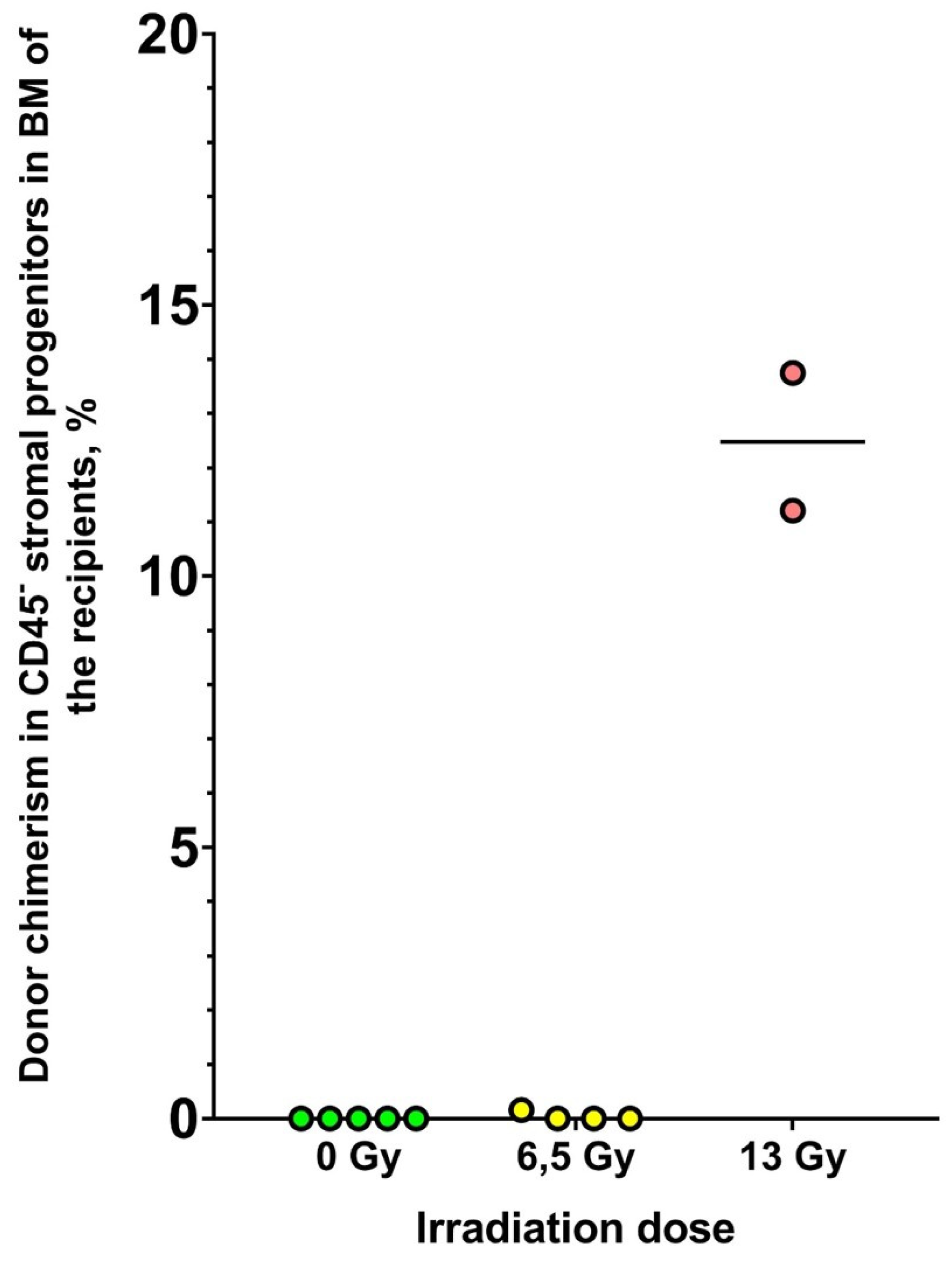

Donor chimerism among CD45

– cells in CFU-F flasks was assessed by ddPCR (

Figure 2).

Donor chimerism in BM stromal cells was shown to be dependent on the irradiation dose of the recipient. None of the unirradiated recipients had donor cells in the subpopulation studied. In the group of recipients irradiated at a dose of 6.5 Gy, only one recipient showed the presence of donor cells; chimerism in this animal was 0.16%. Escalating irradiation of the recipients up to the lethal dose resulted in a significant increase in donor chimerism among the BM stromal cells. In this group, donor chimerism was 11% and 14% (it was not possible to isolate sufficient DNA for analysis in the third surviving recipient of this group).

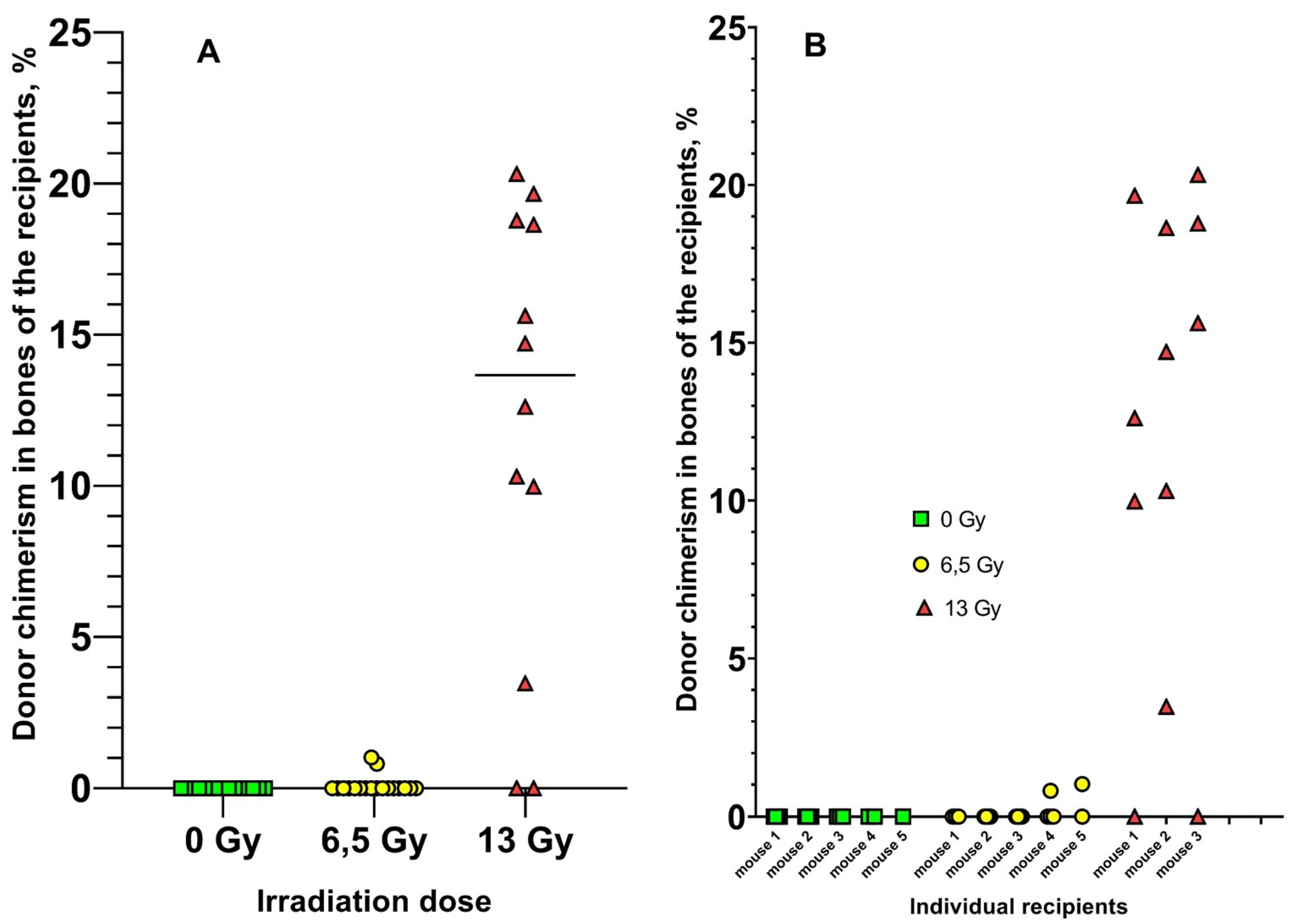

Four bones were obtained from each recipient mouse. DNA was isolated from each bone separately. Donor chimerism was measured in each DNA sample using real-time PCR (

Figure 3).

Donor chimerism was not observed in the bones of unirradiated recipients in any of the 15 samples. Donor chimerism was observed in only 2/18 bones of 6.5 Gy recipients (0.8% and 1%), with a median of 0% in this group. The median donor chimerism in bones of recipients irradiated with 13 Gy was 15%. Thus, the increase in radiation dose to the recipients resulted in a significant increase in donor chimerism in the bones of the recipients.

4. Discussion

In planning the described experiment, we assumed that the function of stem cells (regardless of their tissue affiliation) is physiological self-renewal of the corresponding tissue and its regeneration in case its function is depressed/disturbed for any reason. We assumed that if this statement is true, then in order for MSCs introduced systemically into the recipient's body to successfully home to the BM and start proliferating and differentiating, it is necessary to significantly damage the BM stroma in the recipient beforehand. We chose ionizing radiation as a damaging factor because its destructive effect on stromal progenitor cells has been well established [

20,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. In this experiment, the non-selective nature of the radiation exposure resulted in a complex suppression of marrow stromal function. To reliably determine the relationship between donor chimerism and the degree of stromal damage, we used two doses, a semi-lethal dose of 6.5 Gy and a lethal dose of 13 Gy. As shown in the control group, which was not injected with donor BM after irradiation, the 13 Gy dose received was indeed lethal, as all 6 mice in this group died within 15 days after irradiation. In the group of mice irradiated with 13 Gy, there was a tendency to decrease the concentration of CFU-Fs (

Supplementary Figure S9, p = 0.25). The lack of statistical significance here can be explained by both the small sample size and the fact that donor MSCs could partially replenish the pool of CFU-Fs and replace the damaged CFU-Fs of the recipient.

It has been shown that increased radiation dose and associated damage to recipient BM stromal cells results in a significant increase in the engraftment efficiency of donor mesenchymal progenitor cells. This finding was fully confirmed when donor chimerism was measured in bones of the same mice. The median chimerism in lethally irradiated recipients was 15% compared to 0% in the other two groups. It should be emphasized that when chimerism was measured in bones, osteocytes and osteoblasts were the main cell population tested because they do not detach from the bone when it is washed with a syringe jet, they sit firmly on the surface and require collagenase treatment to detach. On the other hand, when BM cells were infused on the day of irradiation, osteoblasts were not injected into the recipients for the same reason (the BM was extracted from the diaphyseal cavity by the jet stream of the syringe). Consequently, the injected donor MSCs and other stromal progenitor cells not only survived in the recipient's body within 30 days after injection, but also successfully homed to the BM and differentiated into osteoblasts/osteocytes. This suggests that the injected MSCs or their progeny maintained their functionality after intravenous injection. Thus, in two different cellular stromal fractions, using two sensitive methods, an increase in engraftment efficiency of donor mesenchymal cells was demonstrated after their intravenous injection as part of the graft derived from native BM. Thus, the obtained results make us reconsider the potential benefit of using native BM or BM primed with G-CSF for the purposes of regenerative medicine and transplantation hematology.

Another factor that researchers attribute to cases of successful MSC transplantation is the large number of cells injected [

37,

38,

39], while unsuccessful attempts to demonstrate engraftment of the stromal component of BM may be due to an insufficient number of cells injected [

40,

41,

42]. In this experiment, recipient mice were injected with relatively large amounts of donor BM cells. With an average mouse weight of 25 g, unirradiated control recipients received 1.2 x 10

9 cells/kg, while those irradiated with 6.5 Gy and 13 Gy received the same amount - 0.64 x 10

9 cells/kg each. Our results suggest that the number of cells injected, if it is a factor affecting engraftment, is not critical. Despite the fact that twice as many cells were injected into the unirradiated recipients, no engraftment of donor cells occurred in them. On the other hand, with the same number of cells injected, donor chimerism differed significantly in the 6.5 Gy and 13 Gy groups, i.e., the radiation dose appears to be the dominant factor rather than the number of donor cells injected.

This study opens the prospect of creating effective protocols for BM stroma transplantation and creating an alternative strategy of alloHSCT, the main stages of which may be: 1) induction therapy together with eradication therapy aimed at eliminating functionally defective and modified by leukemic cells stroma of the recipient; 2) transplantation of stroma from a donor to fully restore hematopoietic microenvironment; 3) transplantation of HSCs from the same donor to restore hematopoiesis.

Despite the accumulating evidence of the potential benefits of allogeneic BM stroma transplantation, it is necessary to investigate all possible risks to the patient and to ensure appropriate conditions of safety and clinical efficacy. In particular, potential transplantation protocols will require approaches that result in significant damage and even eradication of the recipient's BM stroma. And if engraftment of the donor stromal component does not occur, there will be no HSCs engraftment due to the lack of necessary niches for them. This will result in extremely severe complications, prolonged recovery and even fatal outcomes for the patient. There is also a potential risk of such undesirable phenomena as osteogenesis disorder with formation of severe progressive bone loss. It is known that the introduction of MSCs into the systemic bloodstream is accompanied by a pronounced immunosuppressive effect, which is used in the treatment and prophylaxis of GVHD and autoimmune diseases [

43,

44]. Given the potential intensification of induction and consolidation protocols to achieve profound damage to the stromal component of the BM, the risk of increased incidence of infectious complications and associated mortality should be evaluated [

45]. Relapse is one of the major problems after alloHSCT. Donor MSCs can not only exert antitumor function and replace tumor remodeled stroma with healthy microenvironment, but also re-enter the tumor microenvironment and maintain and stimulate malignant cells [

46,

47,

48,

49]. It is likely that the ability of a tumor to recruit donor MSCs depends on the histological type of the tumor and its molecular characteristics. This is to be determined in further experiments.

The engraftment efficiency of BM stromal progenitor cells is extremely low after their intravenous administration to unirradiated recipients with preserved stroma. Minor damage of the recipient's BM stroma by ionizing radiation does not increase the efficiency of engraftment of BM stromal cells. Successful engraftment of donor stromal progenitor cells requires prior damage to the recipient's BM stroma. BM stromal component transplantation is feasible and achievable. BM stromal transplantation has the potential to become part of an alternative strategy for the treatment of a variety of hematologic and orthopedic diseases associated with impaired function of MSCs and/or BM stroma, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, consisting of combined sequential transplantation of BM stroma and hematopoietic tissue.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

A.E. Bigildeev - concept, experimental procedures with animals, method development and measurement of donor chimerism, ddPCR, RQ-PCR, drafting the manuscript; E.A. Bigildeev - calculation of accuracy of donor chimerism determination; E.S. Bulygina - Sanger sequencing, gel electrophoresis, DNA isolation from bones, manuscript revision; S.V. Tsygankova - DNA isolation from sorted cell populations, measurement of DNA concentration, ddPCR, manuscript revision; M.S. Gusakova - analysis and discussion of results, manuscript revision; O.I. Illarionova - sorting of cell populations, analysis of results, manuscript revision.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/

Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Singh AK, McGuirk JP. Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Historical and Scientific Overview. Cancer research. 2016;76(22):6445-6451. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medinger M, Drexler B, Lengerke C, Passweg J. Pathogenesis of Acquired Aplastic Anemia and the Role of the Bone Marrow Microenvironment. Frontiers in Oncology. 2018;8:587. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Ciceri F, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapies in Europe 2022. CAR-T activity continues to grow; transplant activity has slowed: a report from the EBMT. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2024;59(6):803–812.

- De Felice L, Agostini F, Suriano C, et al. Hematopoietic, Mesenchymal, and Immune Cells Are More Enhanced in Bone Marrow than in Peripheral Blood from Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor Primed Healthy Donors. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation. 2016;22(10):1758-1764. [CrossRef]

- Deotare U, Al-Dawsari G, Couban S, Lipton JH. G-CSF-primed bone marrow as a source of stem cells for allografting: revisiting the concept. Bone marrow transplantation. 2015;50(9):1150-1156. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Luo J, Zhang Z, et al. G-CSF-Mobilized Blood and Bone Marrow Grafts as the Source of Stem Cells for HLA-Identical Sibling Transplantation in Patients with Thalassemia Major. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2019;25(10):2040-2044. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang YJ, Zhao XY, Huang XJ. Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor-Primed Unmanipulated Haploidentical Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Frontiers in immunology. 2019;10:2516. [CrossRef]

- Epah J, Spohn G, Preiß K, et al. Small volume bone marrow aspirates with high progenitor cell concentrations maximize cell therapy dose manufacture and substantially reduce donor hemoglobin loss. BMC medicine. 2023;21(1):360. [CrossRef]

- Hay SB, Ferchen K, Chetal K, Grimes HL, Salomonis N. The Human Cell Atlas bone marrow single-cell interactive web portal. Experimental hematology. 2018;68:51-61. [CrossRef]

- Fruehauf S, Tricot G. Comparison of unmobilized and mobilized graft characteristics and the implications of cell subsets on autologous and allogeneic transplantation outcomes. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16(12):1629-1648. [CrossRef]

- Rieger K, Marinets O, Fietz T, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells remain of host origin even a long time after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell or bone marrow transplantation. Experimental hematology. 2005;33(5):605-611. [CrossRef]

- Villaron EM, Almeida J, López-Holgado N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells are present in peripheral blood and can engraft after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2004;89(12):1421-1427. [PubMed]

- Lin CS, Ning H, Lin G, Lue TF. Is CD34 truly a negative marker for mesenchymal stromal cells? Cytotherapy. 2012;14(10):1159-1163.

- Sidney LE, Branch MJ, Dunphy SE, Dua HS, Hopkinson A. Concise review: evidence for CD34 as a common marker for diverse progenitors. Stem Cells. 2014;32(6):1380–1389. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shono Y, Ueha S, Wang Y, et al. Bone marrow graft-versus-host disease: early destruction of hematopoietic niche after MHC-mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115(26):5401-5411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong Y, Chang YJ, Wang YZ, et al. Association of an impaired bone marrow microenvironment with secondary poor graft function after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2013;19(10):1465-1473. [CrossRef]

- Kong Y, Wang YT, Hu Y, et al. The bone marrow microenvironment is similarly impaired in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients with early and late poor graft function. Bone marrow transplantation. 2016;51(2):249-255. [CrossRef]

- Shipounova IN, Petinati NA, Bigildeev AE, et al. Alterations in multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells from the bone marrow of acute myeloid leukemia patients at diagnosis and during treatment. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2019;60(8):2042-2049. [CrossRef]

- Shipounova IN, Petinati NA, Bigildeev AE, et al. Alterations of the bone marrow stromal microenvironment in adult patients with acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemias before and after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2017;58(2):408-417. [CrossRef]

- Somaiah C, Kumar A, Sharma R, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells show functional defect and decreased anti-cancer effect after exposure to chemotherapeutic drugs. Journal of biomedical science. 2018;25(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Anand T, Bhattacharyya J, Sharma A, Jaganathan BG. K562 chronic myeloid leukemia cells modify osteogenic differentiation and gene expression of bone marrow stromal cells. Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling. 2017;12(2):441-450. [CrossRef]

- Brenner AK, Nepstad I, Bruserud Ø. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Support Survival and Proliferation of Primary Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells through Heterogeneous Molecular Mechanisms. Frontiers in immunology. 2017;8:106. [CrossRef]

- Kim JA, Shim JS, Lee GY, et al. Microenvironmental remodeling as a parameter and prognostic factor of heterogeneous leukemogenesis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer research. 2015;75(11):2222-2231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar A, Bhattacharyya J, Jaganathan BG. Adhesion to stromal cells mediates imatinib resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia through ERK and BMP signaling pathways. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):9535. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mochmann LH, Treue D, Bockmayr M, et al. Proteomic profiling reveals ACSS2 facilitating metabolic support in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer gene therapy. 2024;31(9):1344-1356. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh IH, Jeong SY, Kim JA. Normal and leukemic stem cell niche interactions. Current opinion in hematology. 2019;26(4):249-257. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlando L, Ginolhac A, Zhang G, et al. Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse. Nature. 2013;499(7456):74-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov SA, Mankani MH, Bianco P, Robey PG. Enumeration of the colony-forming units-fibroblast from mouse and human bone marrow in normal and pathological conditions. Stem Cell Res. 2009;2(1):83–94. [CrossRef]

- Soh YQS, Alföldi J, Pyntikova T, et al. Sequencing the mouse Y chromosome reveals convergent gene acquisition and amplification on both sex chromosomes. Cell. 2014;159(4):800–813.

- Holmlund H, Yamauchi Y, Durango G, Fujii W, Ward MA. Two acquired mouse Y chromosome-linked genes, Prssly and Teyorf1, are dispensable for male fertility‡. Biol Reprod. 2022;107(3):752–764. [CrossRef]

- Rombouts WJ, Ploemacher RE. Primary murine MSC show highly efficient homing to the bone marrow but lose homing ability following culture. Leukemia. 2003;17(1):160-170. [CrossRef]

- Nicolay NH, Lopez Perez R, Saffrich R, Huber PE. Radio-resistant mesenchymal stem cells: mechanisms of resistance and potential implications for the clinic. Oncotarget. 2015;6(23): 19366–19380. [CrossRef]

- Sugrue T, Lowndes NF, Ceredig R. Mesenchymal stromal cells: radio-resistant members of the bone marrow. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91(1):5–11. [CrossRef]

- Gynn LE, Anderson E, Robinson G, et al. Primary mesenchymal stromal cells in co-culture with leukaemic HL-60 cells are sensitised to cytarabine-induced genotoxicity, while leukaemic cells are protected. Mutagenesis. 2021;36(6): 419–428. [CrossRef]

- Chertkov JL, Drize NJ, Gurevitch OA, Udalov GA. Hemopoietic stromal precursors in long-term culture of bone marrow: I. Precursor characteristics, kinetics in culture, and dependence on quality of donor hemopoietic cells in chimeras. Exp Hematol. 1983;11(3):231–242.

- Chertkov JL, Gurevitch OA. Radiosensitivity of progenitor cells of the hematopoietic microenvironment. Radiat Res. 1979;79(1):177–186. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piersma AH, Ploemacher RE, Brockbank KG. Transplantation of bone marrow fibroblastoid stromal cells in mice via the intravenous route. Br J Haematol. 1983;54(2):285–290. [CrossRef]

- Sale GE, Storb R. Bilateral diffuse pulmonary ectopic ossification after marrow allograft in a dog. Evidence for allotransplantation of hemopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Hematol. 1983;11(10):961–966.

- Anklesaria P, Kase K, Glowacki J, et al. Engraftment of a clonal bone marrow stromal cell line in vivo stimulates hematopoietic recovery from total body irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(21):7681–7685. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley SA, Knutsen T, Whang-Peng J. The origin of the hematopoietic microenvironment in continuous bone marrow culture. Experimental hematology. 1982;10(4):367-372.

- Wilson FD, Konrad PN, Greenberg BR, Klein AK, Walling PA. Cytogenetic studies on bone marrow fibroblasts from a male-female hematopoietic chimera. Evidence that stromal elements in human transplantation recipients are of host type. Transplantation. 1978;25(2):87–88. [CrossRef]

- Golde DW, Hocking WG, Quan SG, Sparkes RS, Gale RP. Origin of human bone marrow fibroblasts. British journal of haematology. 1980;44(2):183-187. [CrossRef]

- Zaripova LN, Midgley A, Christmas SE, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Pathogenesis and Therapy of Autoimmune and Autoinflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(22):16040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doglio M, Crossland RE, Alho AC, et al. Cell-based therapy in prophylaxis and treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1045168. [CrossRef]

- Vianello F, Dazzi F. Mesenchymal stem cells for graft-versus-host disease: a double edged sword? Leukemia. 2008;22(3):463-465.

- Forte D, García-Fernández M, Sánchez-Aguilera A, et al. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Support Acute Myeloid Leukemia Bioenergetics and Enhance Antioxidant Defense and Escape from Chemotherapy. Cell metabolism. 2020;32(5):829-843. [CrossRef]

- Antoon R, Overdevest N, Saleh AH, Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells as cancer promoters. Oncogene. 2024;43(49):3545-3555. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramuta TŽ, Kreft ME. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells May Decrease Success of Cancer Treatment by Inducing Resistance to Chemotherapy in Cancer Cells. Cancers. 2022;14(15):3761. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee MW, Ryu S, Kim DS, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells in suppression or progression of hematologic malignancy: current status and challenges. Leukemia. 2019;33(3):597-611. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).