Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Galactic cosmic ray (GCR) radiation is a major barrier to human space exploration beyond Earth’s magnetic field protection. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are found in all organs, and they play a critical role in repair and regeneration of tissue. We specifically use engineered bone marrow-derived MSCs as a model to evaluate the effect of radiation exposure during deep space travel and long-duration spaceflight. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression by certain types of cancers has been shown to induce radioresistance. In this study, we tested the feasibility of engineering MSCs to overexpress EGFR (eMSC-EGFR) and evaluated their capacity to tolerate and recover from exposure to x-ray exposure (1 – 20 Gy). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and immunoblotting results have shown that EGFR was efficiently transfected into MSCs and EGFR protein was produced. eMSC-EGFR maintained characteristics of human MSCs as outlined by the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy. Then, both eMSC-EGFR and naïve MSCs were exposed to various dose rates of x-ray irradiation to assess the potential radioprotective role of EGFR overexpression in MSCs. Analysis included post-irradiation evaluation of morphology, cell proliferation, tumorigenic potential, and DNA damage. eMSC-EGFR showed signs of radioresistance compared to naïve MSCs when assessing relative proliferation one week following exposure at doses of 1–8 Gy and significantly lower DNA damage content 24 hours after exposure to 4 Gy. We establish for the first time the feasibility of efficiently generating EGFR overexpressing MSCs as a model for enhancing the human body to tolerate and recover from moderate dose radiation injury in long-term manned space travel.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

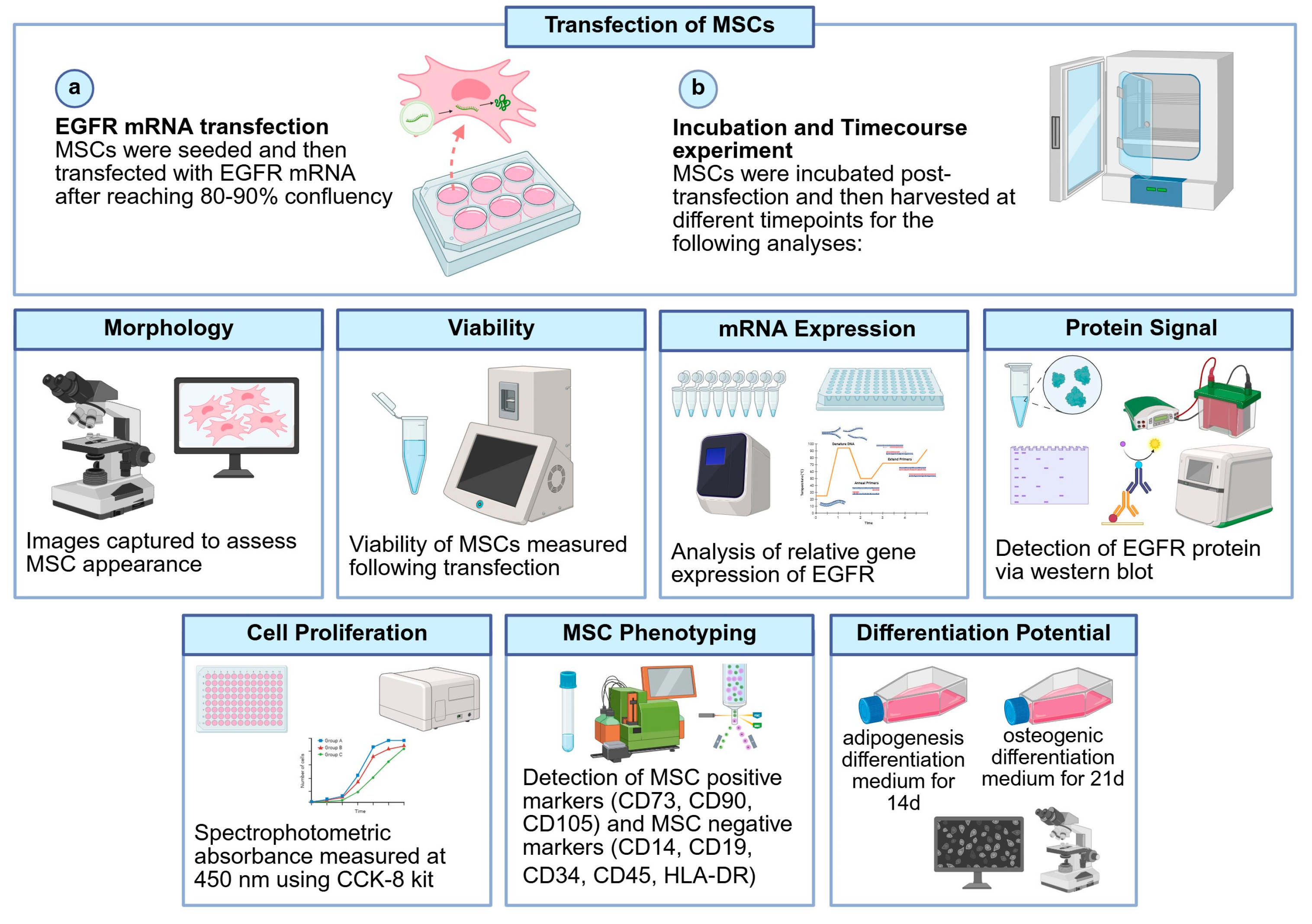

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of mRNA

2.2. Cell Culture and mRNA Transfection

2.3. Viability

2.4. MSC Phenotyping

2.5. Differentiation of MSCs

2.6. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

2.8. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.9. Cell Irradiation (X-Ray)

2.10. Tumorigenicity Assay

2.11. DNA Damage

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

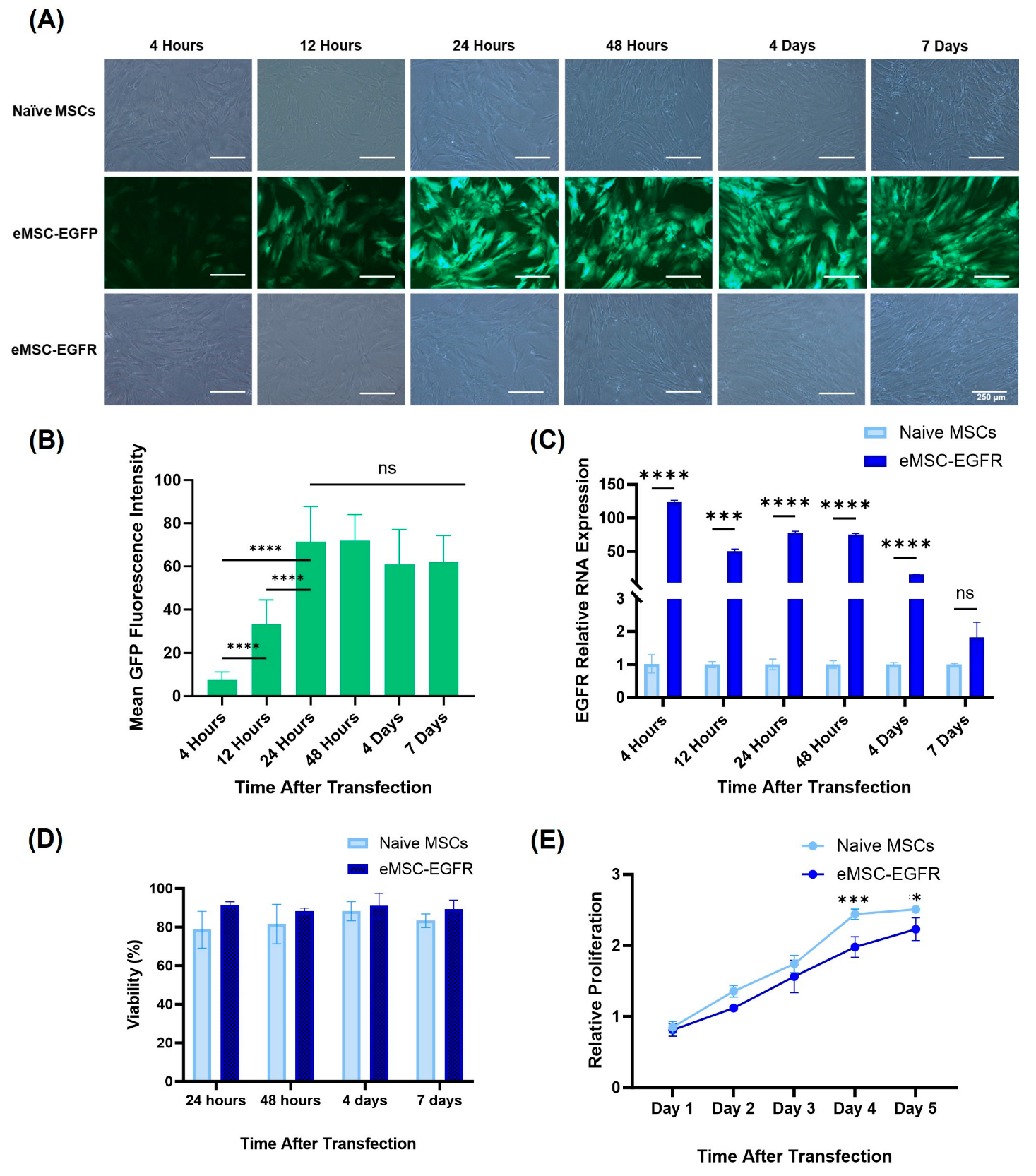

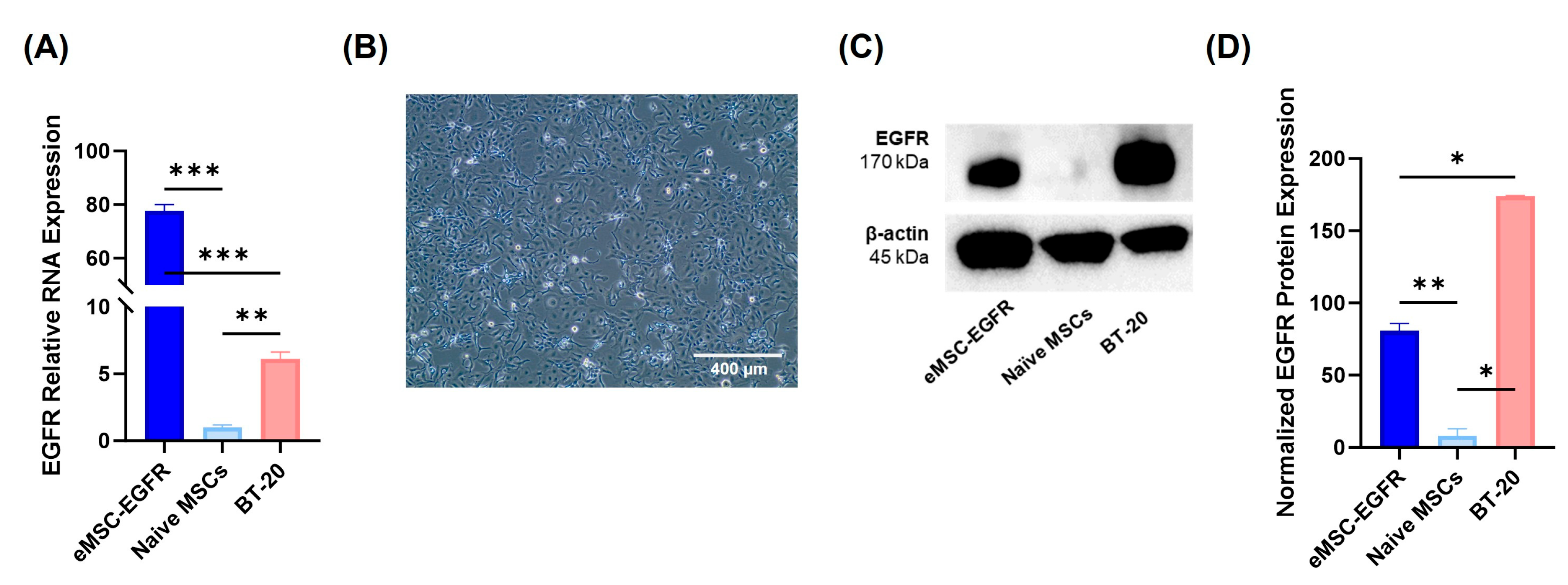

3.2. EGFR mRNA Transfection Efficiency and Protein Expression

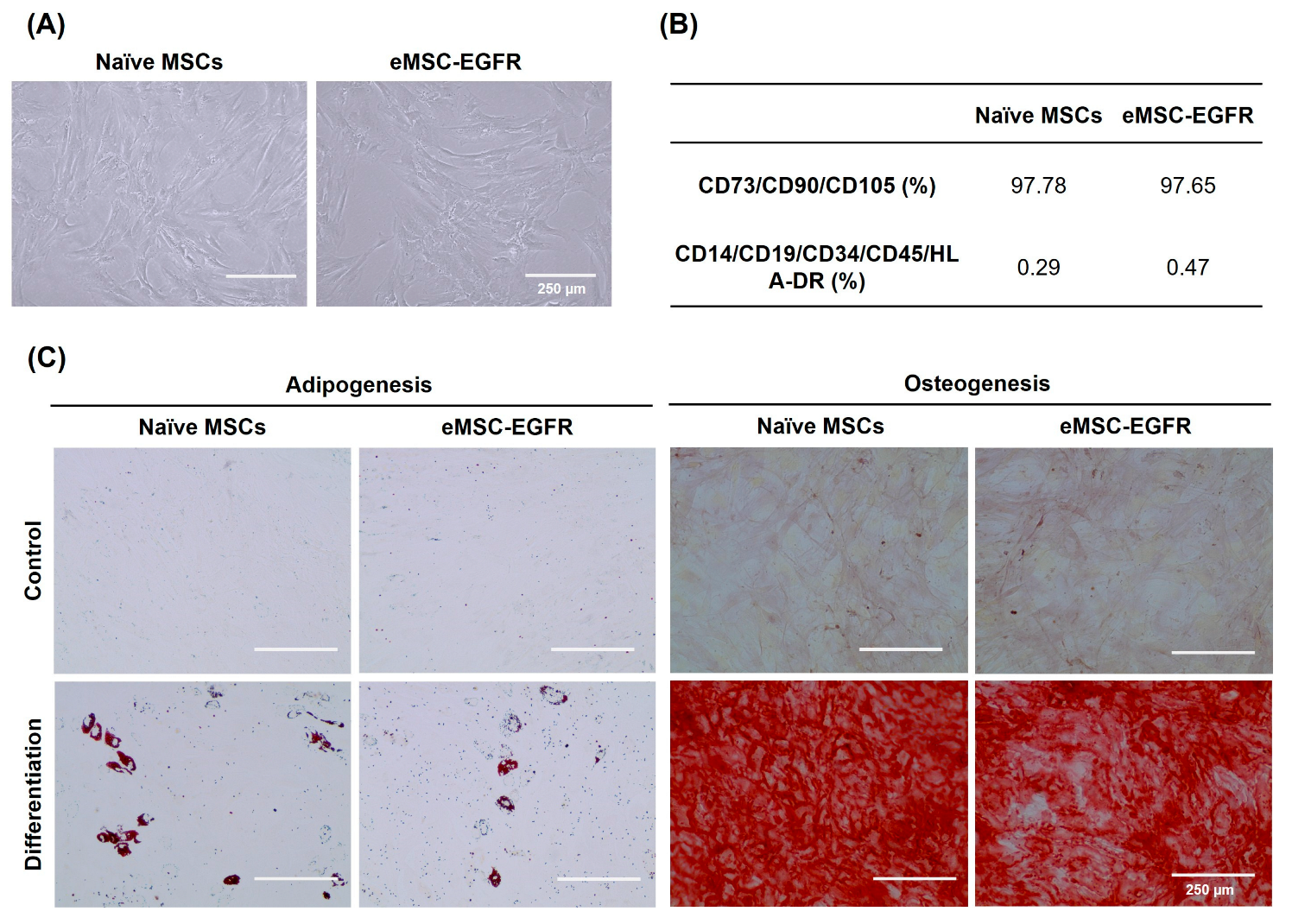

3.2. Characterization of EGFR mRNA-Engineered MSCs

3.3. Cell Morphology and Proliferation Assessment of Irradiated MSCs

3.4. Assessment of Irradiated MSCs for Tumorigenic Potential

3.5. Genomic Integrity Analysis of Irradiated MSCs

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings and Suggested Mechanisms

4.2. Implications for Deep Space Travel

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Jella, K.K.; Jaafar, L.; Li, S.; Park, S.; Story, M.D.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Dynan, W.S. Exposure to galactic cosmic radiation compromises DNA repair and increases the potential for oncogenic chromosomal rearrangement in bronchial epithelial cells. Sci Rep-Uk 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancellor, J.C.; Blue, R.S.; Cengel, K.A.; Auñón-Chancellor, S.M.; Rubins, K.H.; Katzgraber, H.G.; Kennedy, A.R. Limitations in predicting the space radiation health risk for exploration astronauts. Npj Microgravity 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, D.M.; Asaithamby, A.; Bailey, S.M.; Costes, S.V.; Doetsch, P.W.; Dynan, W.S.; Kronenberg, A.; Rithidech, K.N.; Saha, J.; Snijders, A.M.; et al. Understanding Cancer Development Processes after HZE-Particle Exposure: Roles of ROS, DNA Damage Repair and Inflammation. Radiat Res 2015, 183, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, F.A.; To, K.; Cacao, E. Predictions of space radiation fatality risk for exploration missions. Life Sci Space Res 2017, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, F.; Zubair, A.C. Possible impacts of cosmic radiation on leukemia development during human deep space exploration. Leukemia 2025, 39, 1578–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontikoglou, C.; Deschaseaux, F.; Sensebe, L.; Papadaki, H.A. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: biological properties and their role in hematopoiesis and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2011, 7, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, C.; Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Ye, W. The role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in regulating radioresistance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2020, 150, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Jiang, X.; Xiao, H.; Guan, J. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles inhibit HGF/c-Met and EGF/EGFR pathways to accelerate the radiosensitivity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via microRNA-142-5p delivery. Cell Death Discov 2022, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuneo, K.C.; Nyati, M.K.; Ray, D.; Lawrence, T.S. EGFR targeted therapies and radiation: Optimizing efficacy by appropriate drug scheduling and patient selection. Pharmacol Ther 2015, 154, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Porada, G.; Rodman, C.; Kuhlman, B.; Brudvik, E.; Moon, J.; George, S.; Guida, P.; Sajuthi, S.P.; Langefeld, C.D.; Walker, S.J.; et al. Exposure of the Bone Marrow Microenvironment to Simulated Solar and Galactic Cosmic Radiation Induces Biological Bystander Effects on Human Hematopoiesis. Stem Cells Dev 2018, 27, 1237–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, J.; Moll, G. MSCs in Space: Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapeutics as Enabling Technology for Long-Distance Manned Space Travel. Curr Stem Cell Rep 2022, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.J.; Giaccia, A.J. Radiobiology for the Radiologist, 8th Edition ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, 2019; p. 624. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger, J.S.; Epperly, M.W. CNS (Ionizing Irradiation Effects on the Brain, Spinal Cord, and Peripheral Nervous System). In CMCRC Radiobiology Textbook, Greenberger, J.S., Ed.; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID): Bethesda, MD.

- Hall, E.J.; Brenner, D.J. The dose-rate effect revisited: radiobiological considerations of importance in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991, 21, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Krause, D.S.; Deans, R.J.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E.M. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninckx, S.; Pariset, E.; Cekanaviciute, E.; Costes, S.V. Quantification of radiation-induced DNA double strand break repair foci to evaluate and predict biological responses to ionizing radiation. NAR Cancer 2021, 3, zcab046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogakou, E.P.; Pilch, D.R.; Orr, A.H.; Ivanova, V.S.; Bonner, W.M. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 5858–5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Adamski, R.; Chen, J. Focus on histone variant H2AX: to be or not to be. FEBS Lett 2010, 584, 3717–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapko, J.; Talapko, D.; Katalinic, D.; Kotris, I.; Eric, I.; Belic, D.; Mihaljevic, M.V.; Vasilj, A.; Eric, S.; Flam, J.; et al. Health Effects of Ionizing Radiation on the Human Body. Medicina-Lithuania 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.J.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, D.H. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Injury Induced by Ionizing Radiation. Antioxid Redox Sign 2014, 20, 1447–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chancellor, J.C.; Scott, G.B.; Sutton, J.P. Space Radiation: The Number One Risk to Astronaut Health beyond Low Earth Orbit. Life (Basel) 2014, 4, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, E.; Ponsaerts, P.; Lenjou, M.; Nijs, G.; Van Bockstaele, D.R.; Berneman, Z.N.; Van Tendeloo, V.F. RNA-based gene transfer for adult stem cells and T cells. Leukemia 2004, 18, 1898–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiehe, J.M.; Ponsaerts, P.; Rojewski, M.T.; Homann, J.M.; Greiner, J.; Kronawitter, D.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Hombach, V.; Wiesneth, M.; Zimmermann, O.; et al. mRNA-mediated gene delivery into human progenitor cells promotes highly efficient protein expression. J Cell Mol Med 2007, 11, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Kariko, K.; Tureci, O. mRNA-based therapeutics--developing a new class of drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014, 13, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLenachan, S.; Zhang, D.; Palomo, A.B.; Edel, M.J.; Chen, F.K. mRNA transfection of mouse and human neural stem cell cultures. PLoS One 2013, 8, e83596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, T.; DiAndreth, B.; Teague, B.; Weiss, R. Programming gene and engineered-cell therapies with synthetic biology. Science 2018, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Zhang, C.; Delawary, M.; Korchak, J.A.; Suda, K.; Zubair, A.C. Development and evaluation of IL-6 overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2022, 16, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishiro, A.; Miura, Y.; Iwasa, M.; Fujii, S.; Sugino, N.; Andoh, A.; Hirai, H.; Maekawa, T.; Ichinohe, T. Effects of acute exposure to low-dose radiation on the characteristics of human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal/stem cells. Inflamm Regen 2017, 37, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Xiao, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, L.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ji, K.; Wang, J.; et al. Radiation Responses of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived From Different Sources. Dose Response 2019, 17, 1559325819893210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Jucker, M. The Role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling in Tumor Radioresistance and Advances in Inhibitor Research. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, W.H.; Schaue, D. Radiation-induced tissue damage and response. J Pathol 2020, 250, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Jang, D.J. Protein kinase CK2 regulates cytoskeletal reorganization during ionizing radiation-induced senescence of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Res 2009, 69, 8200–8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuraud, K.; Richardson, D.B.; Cardis, E.; Daniels, R.D.; Gillies, M.; O'Hagan, J.A.; Hamra, G.B.; Haylock, R.; Laurier, D.; Moissonnier, M.; et al. Ionising radiation and risk of death from leukaemia and lymphoma in radiation-monitored workers (INWORKS): an international cohort study. Lancet Haematol 2015, 2, E276–E281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosangi, B.; Davids, M.; Somarouthu, B.; Alessandrino, F.; Giardino, A.; Ramaiya, N.; Krajewski, K. Review of targeted therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: what a radiologist needs to know about CT interpretation. Cancer Imaging 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, E.S. Ionising radiation and cancer risks: what have we learned from epidemiology? Int J Radiat Biol 2009, 85, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandi, R.; Larsen, A.B.; Andersen, P.; Stockhausen, M.T.; Poulsen, H.S. Mechanisms for oncogenic activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Cell Signal 2007, 19, 2013–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.Q.; Fang, W.F.; Mu, L.B.; Tang, Y.N.; Gao, L.; Ren, S.X.; Cao, D.F.; Zhou, L.X.; Zhang, A.Q.; Liu, D.R.; et al. Overexpression of wildtype EGFR is tumorigenic and denotes a therapeutic target in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 3884–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greulich, H.; Chen, T.H.; Feng, W.; Jänne, P.A.; Alvarez, J.V.; Zappaterra, M.; Bulmer, S.E.; Frank, D.A.; Hahn, W.C.; Sellers, W.R.; et al. Oncogenic transformation by inhibitor-sensitive and -resistant EGFR mutants. Plos Med 2005, 2, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Sun, X.J.; Han, Q.B.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.P.; Gu, J.L.; Wu, W.; Zhang, G.; Hu, J.L.; Sun, W.Y.; et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor protein overexpression and gene amplification are associated with aggressive biological behaviors of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett 2015, 10, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takehana, T.; Kunitomo, K.; Suzuki, S.; Kono, K.; Fujii, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Ooi, A. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor in gastric carcinomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003, 1, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, A.; Takehana, T.; Li, X.; Suzuki, S.; Kunitomo, K.; Iino, H.; Fujii, H.; Takeda, Y.; Dobashi, Y. Protein overexpression and gene amplification of HER-2 and EGFR in colorectal cancers: an immunohistochemical and fluorescent in situ hybridization study. Mod Pathol 2004, 17, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawa, M.; Suzuki, S.; Dobashi, Y.; Yamane, T.; Kono, K.; Enomoto, N.; Ooi, A. EGFR protein overexpression and gene amplification in squamous cell carcinomas of the esophagus. Int J Cancer 2006, 118, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normanno, N.; De Luca, A.; Bianco, C.; Strizzi, L.; Mancino, M.; Maiello, M.R.; Carotenuto, A.; De Feo, G.; Caponigro, F.; Salomon, D.S. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in cancer. Gene 2006, 366, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, H.M.; Brdlik, C.M.; Schreiber, H. Signal integration: a framework for understanding the efficacy of therapeutics targeting the human EGFR family. J Clin Invest 2008, 118, 3574–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Sheng, L.; Mao, W. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of esophageal carcinoma and the suggested mechanisms of action. Oncol Lett 2013, 5, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Z.H.; Su, W.; Holm, R.; Nesland, J.M. Lack of expression of c-erbB-2 oncoprotein in human esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Anticancer Res 1995, 15, 2797–2798. [Google Scholar]

- Sunpaweravong, P.; Sunpaweravong, S.; Puttawibul, P.; Mitarnun, W.; Zeng, C.; Baron, A.E.; Franklin, W.; Said, S.; Varella-Garcia, M. Epidermal growth factor receptor and cyclin D1 are independently amplified and overexpressed in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2005, 131, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato-Kuwabara, Y.; Neves, J.I.; Fregnani, J.H.; Sallum, R.A.; Soares, F.A. Evaluation of gene amplification and protein expression of HER-2/neu in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma using Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH) and immunohistochemistry. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Oka, K.; Yamasaki, S.; Sonoue, H.; Kajiyama, Y.; Tsurumaru, M.; Sasai, K. c-erbB-2 oncoprotein expression related to chemoradioresistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003, 57, 1323–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotoh, M.; Takiuchi, H.; Kawabe, S.; Ohta, S.; Kii, T.; Kuwakado, S.; Katsu, K. Epidermal growth factor receptor is a possible predictor of sensitivity to chemoradiotherapy in the primary lesion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2007, 37, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delektorskaya, V.V.; Chemeris, G.Y.; Zavalishina, L.E.; Ryazantseva, A.A.; Grigorchuk, A.Y.; Kononets, P.V.; Davydov, M.I. Squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: evaluation of the status of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR and HER-2) by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. Bull Exp Biol Med 2010, 149, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Ueda, M.; Ando, N.; Ozawa, S.; Shimizu, N.; Kitajima, M. Further evidence for prognostic significance of epidermal growth factor receptor gene amplification in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 1996, 2, 909–914. [Google Scholar]

- Dobynde, M.; Guo, J.N. Guidelines for radiation-safe human activities on the Moon. Nat Astron 2024, 8, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitlin, C.; Hassler, D.M.; Cucinotta, F.A.; Ehresmann, B.; Wimmer-Schweingruber, R.F.; Brinza, D.E.; Kang, S.; Weigle, G.; Bottcher, S.; Bohm, E.; et al. Measurements of energetic particle radiation in transit to Mars on the Mars Science Laboratory. Science 2013, 340, 1080–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wimmer-Schweingruber, R.F.; Yu, J.; Wang, C.; Fu, Q.; Zou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Hou, D.; Bottcher, S.I.; et al. First measurements of the radiation dose on the lunar surface. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachev, T.P.; Tomov, B.T.; Matviichuk, Y.N.; Dimitrov, P.G.; Bankov, N.G. High dose rates obtained outside ISS in June 2015 during SEP event. Life Sci Space Res (Amst) 2016, 9, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terp, M.G.; Jacobsen, K.; Molina, M.A.; Karachaliou, N.; Beck, H.C.; Bertran-Alamillo, J.; Gimenez-Capitan, A.; Cardona, A.F.; Rosell, R.; Ditzel, H.J. Combined FGFR and Akt pathway inhibition abrogates growth of FGFR1 overexpressing EGFR-TKI-resistant NSCLC cells. NPJ Precis Oncol 2021, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Sun, M.M.; Zhang, G.G.; Yang, J.; Chen, K.S.; Xu, W.W.; Li, B. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.J.; Nirodi, C.S. The epidermal growth factor receptor: a role in repair of radiation-induced DNA damage. Clin Cancer Res 2007, 13, 6555–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, Y.W.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, S.; Hwang, C.H.; Lee, C.S.; Hwang, G.; Kim, H.R.; Roe, J.S.; Song, J. Correction: EGFR inhibits TNF-alpha-mediated pathway by phosphorylating TNFR1 at tyrosine 360 and 401. Cell Death Differ 2025, 32, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serag, M.I.; Tawfik, S.S.; Badr, S.M.I.; Eisa, H.M. New oxadiazole and pyrazoline derivatives as anti-proliferative agents targeting EGFR-TK: design, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking study. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, V.Y.; Roos, M.; Termini, C.M.; Signaevskaia, L.; Quarmyne, M.; Lin, P.K.; Pang, A.; Kan, J.; et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent DNA repair promotes murine and human hematopoietic regeneration. Blood 2020, 136, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Wang, Q.; Yao, X.; Yang, J. The Role of DNA Damage Induced by Low/High Dose Ionizing Radiation in Cell Carcinogenesis. Exploratory Research and Hypothesis in Medicine 2021, 6, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhuang, W.; Han, B.; Song, Z.; Guo, W.; Luo, F.; Wu, L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Dong, X.; et al. Phase 1b trial of anti-EGFR antibody JMT101 and Osimertinib in EGFR exon 20 insertion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumbrink, H.L.; Heimsoeth, A.; Sos, M.L. The next tier of EGFR resistance mutations in lung cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaux, J.P.; Le, X.; Vijayan, R.S.K.; Hicks, J.K.; Heeke, S.; Elamin, Y.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Udagawa, H.; Skoulidis, F.; Tran, H.; et al. Structure-based classification predicts drug response in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Nature 2021, 597, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Guo, H.; Xia, Y.; Le, X.; Tan, D.S.W.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Zhou, C. The changing treatment landscape of EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2025, 22, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Aksoy, O.; Zheng, T.; Fan, Q.W.; Weiss, W.A. Epidermal growth factor receptor and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma: signaling pathways and targeted therapies. Oncogene 2018, 37, 1561–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.L.; Hung, M.C. The role of HER2, EGFR, and other receptor tyrosine kinases in breast cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2016, 35, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Bonner, J.A.; Bredel, M. EGFR Mutations in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, B.; Vijayakumar, M.; Priya, K.; Kim, J.H.; Prabakaran, D.S.; Shahid, M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.; Alsaidan, M.; Othman Bahakim, N.; Hassan Abdelzaher, M.; et al. EGFR-Based Targeted Therapy for Colorectal Cancer-Promises and Challenges. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolay, N.H.; Lopez Perez, R.; Saffrich, R.; Huber, P.E. Radio-resistant mesenchymal stem cells: mechanisms of resistance and potential implications for the clinic. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 19366–19380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.; Zhang, B.; Shao, L.; Song, W.; Shi, W.; Wang, L.; Xu, T.; Li, D.; Gao, X.; Qu, Y.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells over-expressing cxcl12 enhance the radioresistance of the small intestine. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Li, X.; Fu, Q.L. Mechanisms underlying the protective effects of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy. Cell Mol Life Sci 2020, 77, 2771–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).