1. Introduction

Radiation exposure, whether from environmental, workplace, or medical sources, has significant health implications, with its effects increasing in proportion to dose and dose rate [

1,

2]. Ionizing radiation disrupts normal cellular functions, including metabolism, proliferation, and differentiation, leading to mutations, apoptosis, necroptosis, and senescence in radiation-sensitive cells [

3]. While high-dose radiation is well known to induce severe tissue damage, the effects of low-dose radiation (LDR, ≤0.2 Gy) remain controversial [

4]. Some studies suggest potential beneficial effects, yet the cumulative effect of prolonged low-dose exposure remains inadequately understood. Even with the same cumulative dose, biological and histological responses vary depending on exposure duration and rate, influencing damage and defense mechanisms.

The male reproductive system is particularly vulnerable to ionizing radiation due to the high sensitivity of testicular tissue [

4,

5]. Even low doses can disrupt spermatogenesis, with as little as 0.1 Gy impairing sperm production and potentially leading to temporary or permanent infertility [

6]. Structural abnormalities, particularly within the seminiferous tubules, further highlight the testis's susceptibility to radiation-induced damage. While short-term low-dose-rate exposure has minimal effects on testicular histology [

4,

7], prolonged exposure may amplify oxidative stress, fibrosis, and apoptosis [

8,

9]. Continuous LDR radiation exposure (2 Gy, for 21 days at a 3.49 mGy/h) has been shown to reduce testicular weight, disrupt seminiferous tubule integrity, and increase oxidative stress and epigenetic markers [

4], all of which may contribute to fibrotic progression.

Fibrosis involves the replacement of normal tissue with disorganized collagen fibers and excessive extracellular matrix (ECM), leading to tissue remodeling, organ dysfunction, and increased morbidity. Radiation-induced fibrosis causes irreversible damage [

8,

9]

, yet testicular fibrosis from radiation exposure remains poorly studied. In fibrotic testes, blood-testis barrier disruption depletes spermatogenic cells, reduces spermatogenesis, and increases peritubular myoid cells and fibroblasts. Interstitial immune cell infiltration and vascular inflammation further contribute to ECM accumulation, exacerbating fibrosis and ultimately leading to irreversible male infertility [

10]

. Although direct research on LDR radiation-induced testicular fibrosis is limited, existing studies on testicular structure and function suggest that prolonged radiation exposure induces oxidative stress and histological damage, possibly contributing to fibrotic changes.

This study investigated the effects of LDR radiation exposures at 3.46, 1.29, and 0.39 mGy/h for 21 days on the testes of C57BL/6 mice, focusing on testicular fibrosis. By comparing dose-dependent changes, our findings provide critical insights into the cumulative risks of long-term LDR radiation exposure and its potential impact on reproductive health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Central Lab. Animal Inc. (Seoul, Korea) and housed in a specific pathogen-free facility. Environmental conditions were maintained at 23 ± 2°C with 50 ± 5% relative humidity, artificial lighting from 08:00 to 20:00, and 13–18 air changes per hour. Mice were provided a standard laboratory diet. All experimental procedures followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, 8th edition, revised 2011) [

11] and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Dongnam Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences (DIRAMS) and Chonnam National University (approval no. CNU IACUC-YB-2024-172).

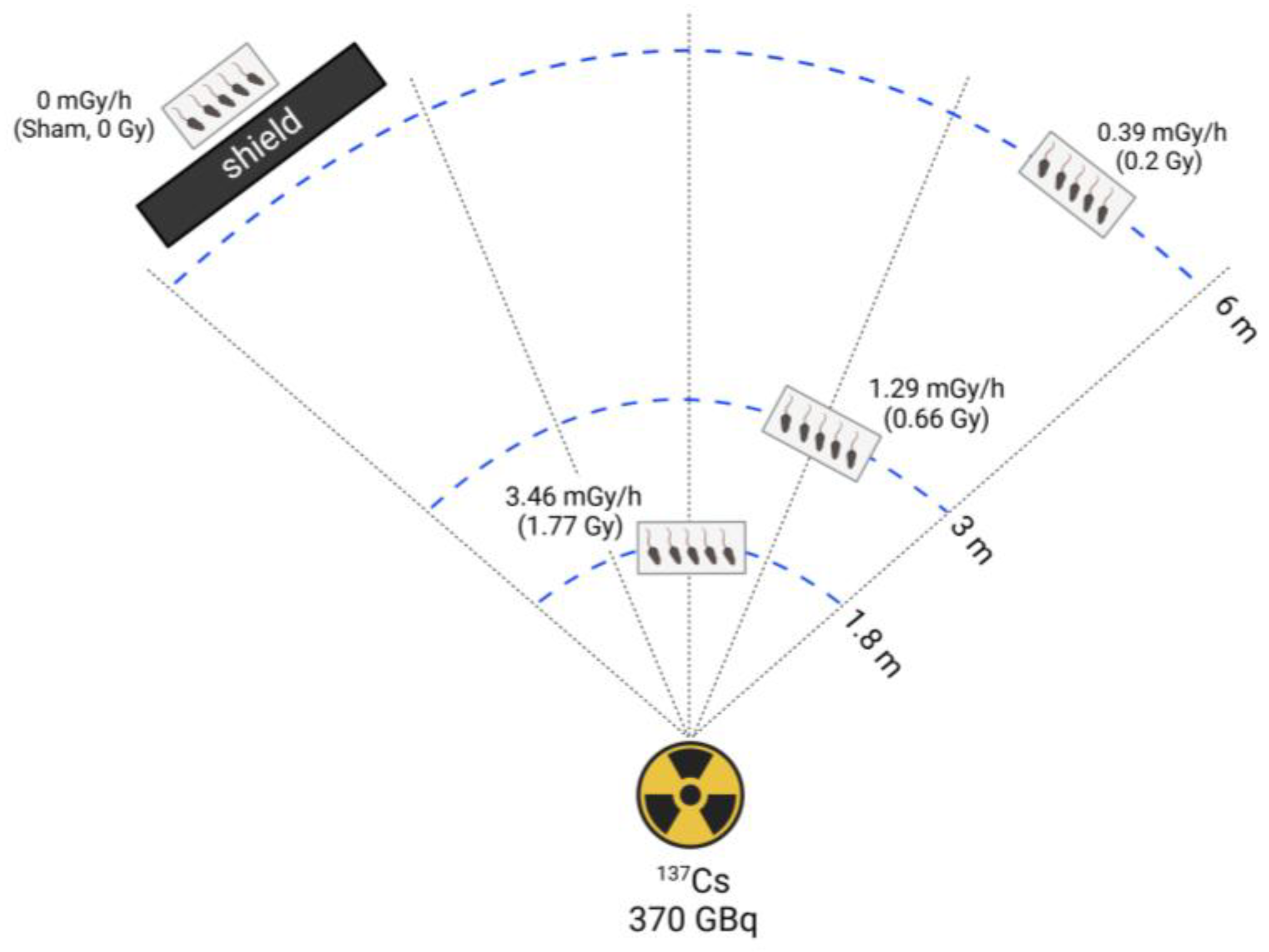

2.2. Radiation Exposure

Mice were randomly assigned to four groups (n = 5 per group): sham, 0.39, 1.29, and 3.46 mGy/h radiation exposure. Low-dose-rate (LDR) irradiation was performed following a previously described method [

11] using a

137Cs source (370 GBq) at the DIRAMS LDR irradiation facility. Mice were continuously exposed for 21 days, except during routine cage cleaning and feeding. Radiation doses were assigned based on cage distance from the source. The sham group was handled identically but without radiation exposure. The 0.39, 1.29, and 3.46 mGy/h groups were positioned at 6 m, 3 m, and 1.8 m from the radiation source, respectively. Over a 21-day exposure period, the total absorbed doses were 0.2 Gy, 0.66 Gy, and 3.46 mGy/h for the 0.39, 1.29, and 3.46 mGy/h groups, respectively. A shielding barrier was employed to completely block radiation exposure in the sham group (

Figure 1). After irradiation, mice were sacrificed, and tissue samples were collected for analysis.

2.3. Chemicals

All chemicals used in this study were tissue culture grade and, unless otherwise specified, were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (MO, USA).

2.4. Testis and Epididymis Isolation and Histological Staining

Testes and epididymides were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight, rinsed in 0.1 M PBS, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded testicular tissues were sectioned into 5 μm slices, mounted on gelatin-coated slides, and air-dried. The sections were deparaffinized in xylene (twice for 5 min each), rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 80%, 70%), and rinsed in double-distilled water.

2.4.1. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

The H&E staining was carried out as described previously [

12]. The rehydrated tissue slides were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min and eosin for 1 min. Sections were then dehydrated in graded ethanol (70%–100%), cleared in xylene, and mounted with Permount (Fisher Chemical, Geel, Belgium). Images were captured using a BX61VS microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and five sections per sample were analyzed.

2.4.2. Sirius Red Staining

The rehydrated tissue slides were incubated with Picro-Sirius Red solution (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 60 min at room temperature. After rinsing in 0.5% acetic acid and absolute alcohol, sections were dehydrated and mounted with synthetic resin. Sirius Red-positive areas were quantified using Fiji ImageJ software.

2.4.3. Masson’s Trichrome Staining

The rehydrated tissue slides were mordanted in Bouin’s solution (56–64°C) for 60 min. After cooling and rinsing, sections were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min, followed by Biebrich Scarlet-Acid Fuchsin for 15 min. Collagen fibers were differentiated using phosphotungstic/phosphomolybdic acid, then stained with Aniline Blue for 5–10 min. Sections were treated with 1% acetic acid for contrast enhancement, dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted with synthetic resin.

2.5. TUNEL Staining

Apoptotic signals in the testes were detected using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, POD (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol. To enhance permeability, the testicular sections were incubated with Proteinase K (10–20 μg/mL in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) at 37°C for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min at room temperature, followed by PBS rinsing. A reaction mixture is freshly prepared by combining Enzyme Solution and Label Solution. Fifty microliters of the TUNEL reaction mixture were applied to each section and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour in the dark. Negative controls were processed with Label Solution only (without Enzyme Solution) to rule out nonspecific staining. In contrast, positive controls were pretreated with DNase I (3 U/mL in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 10 mM MgCl₂ and 1 mg/mL BSA) for 10 min at room temperature to induce DNA strand breaks before the TUNEL reaction. After PBS washes, Converter-POD solution was applied and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. The signal was visualized using a DAB substrate until a brown reaction product appeared. Slides were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), dehydrated in graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted with a permanent mounting medium. Apoptotic cells were identified as brown-stained nuclei under a light microscope. Green fluorescence signals were detected before Converter-POD was added using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM-900, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.6. Comet Assay

Microscope slides were precoated with 1% normal melting point (NMP) agarose, overlaying with a coverslip, and allowing the gel to set at room temperature. Coverslips were removed, and the slides were air-dried overnight. Frozen tissue samples were thawed in ice-cold PBS to minimize further DNA damage. Tissue was finely minced and homogenized, then filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension. Cells were centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was removed. 2 × 10⁴ cells were suspended in 500 μL PBS, mixed with an equal volume of 1% low melting point (LMP) agarose (final concentration 0.5%) maintained at 37°C, and gently pipetted to mix. The cell-agarose suspension was immediately pipetted onto the agarose-coated slides, covered with a 22 × 22 mm coverslip, and allowed to solidify at 4°C for 5 min. Coverslips were removed, and the slides were immersed in freshly prepared lysis buffer (2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCL, 1% Triton X-100, 10% DMSO) or 1 hour at 4°C. Slides were rinsed with distilled water, then placed in alkaline electrophoresis buffer (300 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, pH 13) for 40 min at 4°C to allow DNA unwinding. Electrophoresis was conducted at 25 V and 300 mA for 30 min in the same buffer. After electrophoresis, slides were neutralized in Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer (pH ~8) for 10 min, repeated three times at 4°C. DNA was stained by covering each slide with 600 μL of fluorescent dye solution (Greenstar Necleic Acid Staining Solution, Bioneer) for 5 min in the dark, followed by a rinse with distilled water. Slides were visualized using a fluorescence microscope. % tail DNA was quantified using OpenScore 2.0.

2.7. Measurement of Total Free Radical Activity

Following the manufacturer's protocol, the total free radical activity was assessed using the Oxiselect™ In Vitro ROS/RNS Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA). Briefly, DCF standards were prepared by diluting a 1 mM DCF stock in 1× PBS to a final concentration range of 0–10 μM. Tissue lysates (50 µL) or DCF standards were added to a 96-well black-bottom fluorescence plate (Nunclon™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Roskilde, Denmark), followed by the addition of 50 µL of 1× catalyst. The plate was mixed and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Next, 100 µL of DCFH solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated in the dark for 45 min at room temperature. Fluorescence was measured using a GloMax® Explorer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm. This assay utilizes a quenched fluorogenic probe, dichlorodihydrofluorescein DiOxyQ (DCFH-DiOxyQ), explicitly detecting ROS/RNS. Upon reaction with ROS/RNS, the probe undergoes rapid oxidation to fluorescent DCF, with fluorescence intensity directly proportional to the sample's total ROS/RNS levels.

2.8. Isolation of Total RNA and Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from testis using TRIzol™ Reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After washing cells with 1× PBS, TRIzol™ was added directly to the culture dish, and cells were lysed by pipetting. The homogenate was transferred to an Eppendorf tube, incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and mixed with chloroform (20% of TRIzol™ volume). After vigorous shaking and a 3-min incubation, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The aqueous phase was collected, mixed with 100% isopropanol, and incubated for 10 min before centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. RNA pellets were washed with 75% ethanol, centrifuged at 7,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, air-dried, and resuspended in DEPC-treated RNase-free water. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using 3 μg of total RNA and the DiaStart™ RT Kit (SolGent, Daejeon, Korea). PCR amplification was conducted using first-strand cDNA, Taq polymerase (G-Taq, Cosmo Genetech, Seoul, Korea), and specific primers for mouse ACTA2 (BC064800.1, forward: 5’-TCATTGGGATGGAGTCAGCG-3’, reverse: 5’-AATGCCTGGGTACATGGTGG-3’). GAPDH (GU214026.1, forward: 5’-ACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGG-3’, reverse: 5’-CACATTGGGGGTAGGAACAC-3’) was used as a loading control. Real-time PCR was conducted using the TOPrealTM SYBR Green 2x PreMix (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea) on a LightCycler® 480 II/96 (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The protocol included an initial denaturation at 95℃ for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95℃ for 30 sec, annealing at 60℃ for 30 sec, and extension at 72℃ for 30 sec. Real-time PCR data were analyzed statistically with the 2−ΔΔCt method to determine mRNA level changes, with mRNA expression of target genes normalized to GAPDH levels.

2.9. Statistical analysis

The data are represented as the mean ± S.D. Significant differences between groups were evaluated using a one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni test (OriginPro2020, OriginLab Corp., MA, USA). A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

3. Results

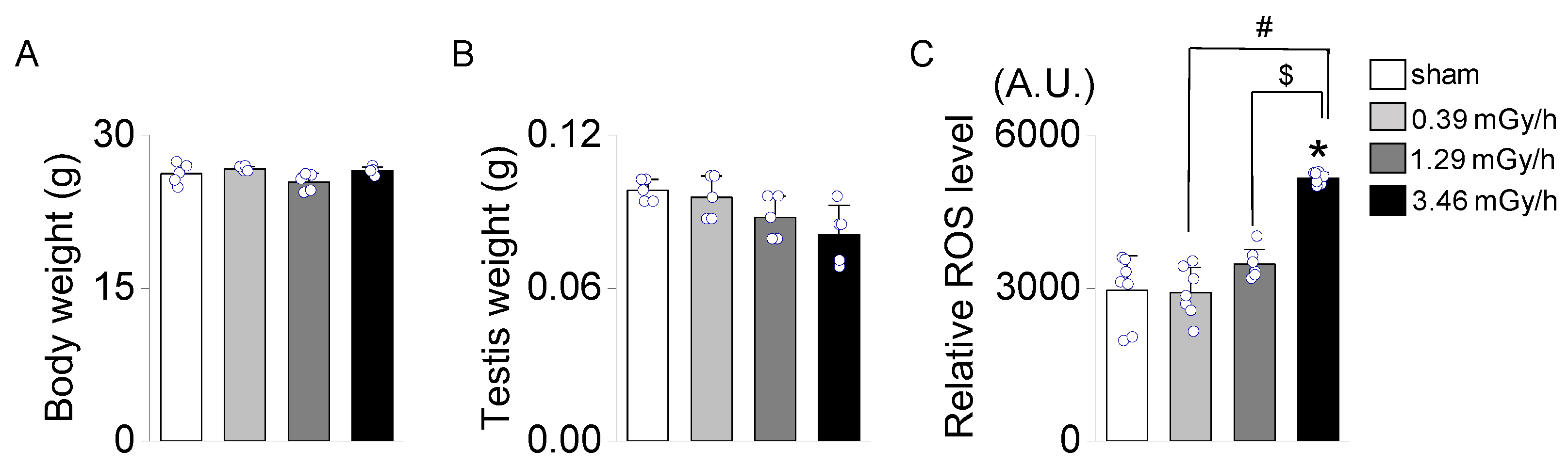

3.1. Effect of Low-Dose-Rate (LDR) Radiation on Testicular Oxidative Stress

No significant differences in body weight were observed among the experimental groups (sham, 0.39, 1.29, and 3.46 mGy/h;

Figure 2A). Similarly, testis weight did not differ significantly across the groups (

Figure 2B). However, the relative levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) were significantly elevated in the 3.46 mGy/h group compared to the sham group (p < 0.05,

Figure 2C).

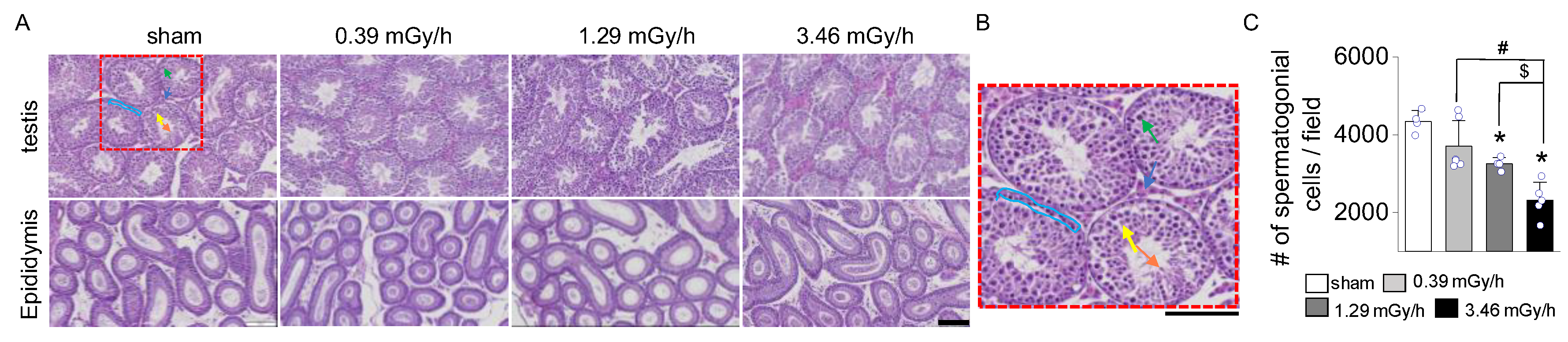

3.2. Histopathological Analysis of Testicular Tissue

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed dose-dependent structural damage to the seminiferous tubules and a reduction in spermatogenic cells in all radiation-exposed groups. In the sham group, the seminiferous tubules appeared intact and well-preserved, with a continuous basal membrane and no observable disruptions. Spermatogenic cells were abundant and arranged in distinct layers. In contrast, radiation-exposed groups exhibited moderate structural damage, including thinning and disruption of the basal membrane (

Figure 3A). In addition, although it is unclear whether there is a significant difference in the diameter of the seminiferous tubules in the testis, exposure to LDR radiation appears to reduce the epithelial cell density in a dose-dependent manner. No notable structural differences were observed in the epididymis among the groups. Representative structures within the seminiferous tubules are shown in the magnified image, including spermatocytes, Sertoli cells, spermatids, spermatogonia, and Leydig cells in the interstitial space (

Figure 3B). The number of spermatogenic cells was noticeably reduced in the 3.46 mGy/h group compared to the sham group (p < 0.05,

Figure 3C). The 3.46 mGy/h group also showed visible disorganization of cell layers in the epididymis.

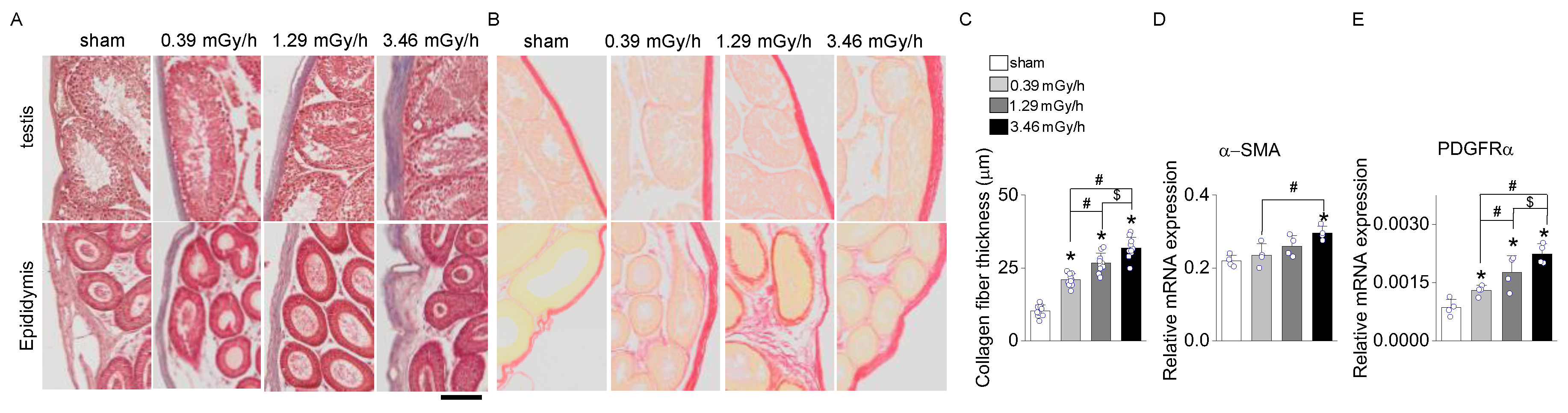

3.3. Fibrosis Assessment Following LDR Radiation Exposure

Masson's Trichrome and Sirius Red staining were performed on testis and epididymis tissues following LDR radiation exposure to assess radiation-induced fibrosis. In the sham group, collagen deposition was minimal, confined to the basal membrane and interstitial regions of the seminiferous tubules in the testis and the connective tissue surrounding the epididymal ducts (

Figure 4A,B). In contrast, mice exposed to 0.39, 1.29, and 3.46 mGy/h showed a dose-dependent increase in collagen accumulation (

Figure 4A–C). The 3.46 mGy/h group exhibited the most pronounced collagen deposition, with visibly thickened collagen fibers in both the testis and epididymis. Furthermore, expression analyses of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA,

ACTA2) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (

PDGFRα) in testicular tissue revealed significant upregulation of these fibrosis-associated genes in the 3.46 mGy/h group compared to the sham group (

Figure 4D,E).

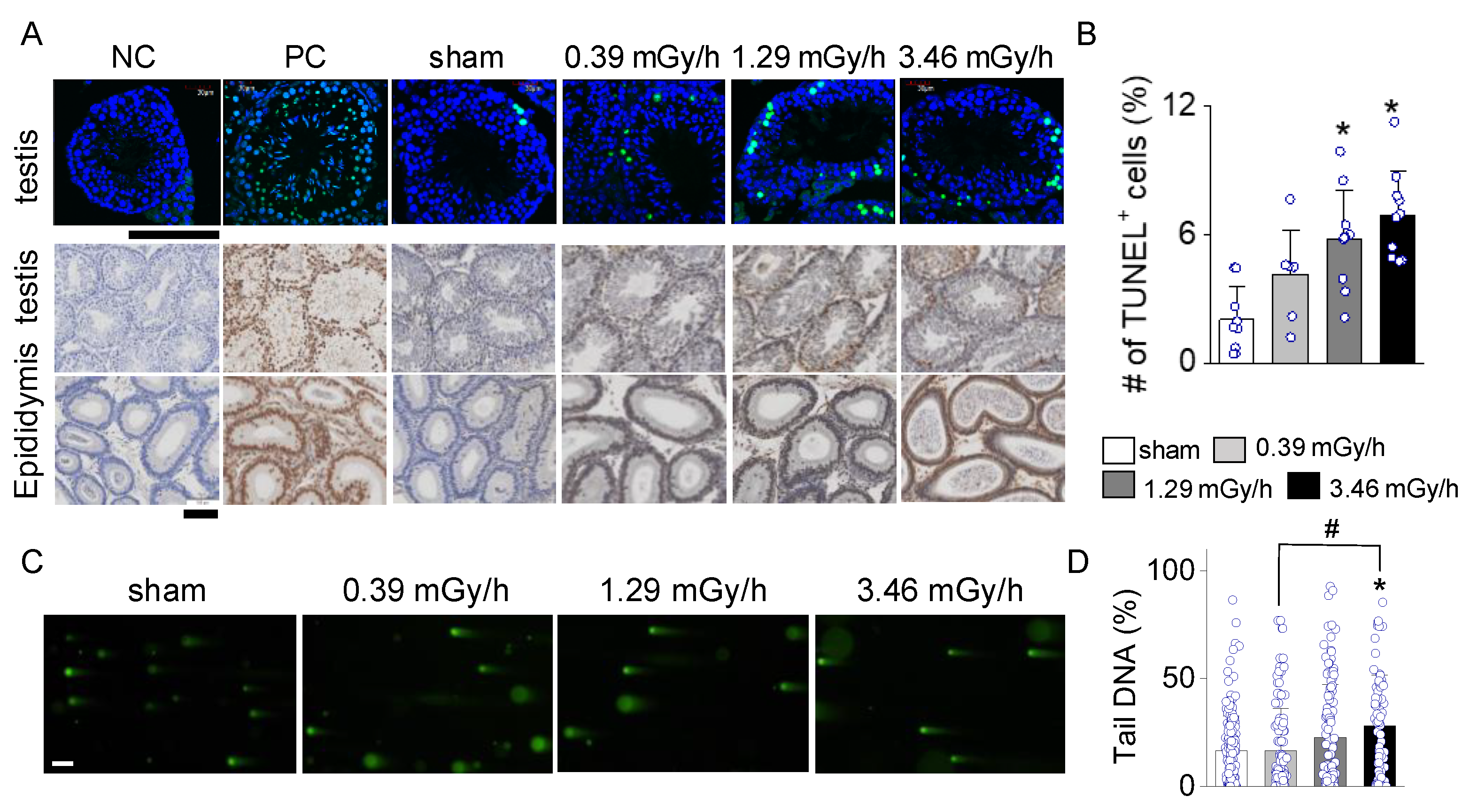

3.4. Increase in Apoptotic Signal in LDR-Exposed Experimental Groups

TUNEL staining assessed apoptosis in testicular and epididymal tissues in sham and LDR-exposed groups (0.39, 1.29, and 3.46 mGy/h). As shown in

Figure 5A, the TUNEL-positive cells (green fluorescence in upper panels, brown signal in lower panels) in testicular tissue increased progressively with radiation dose. The sham group exhibited minimal TUNEL staining, similar to the negative control (NC). The 1.29 mGy/h and 3.46 mGy/h groups showed a marked increase in TUNEL-positive cells compared to the sham. The epididymal tissues followed a similar trend, with increased TUNEL staining intensity at higher radiation doses, particularly in the 3.46 mGy/h group. The bar graph shows a statistically significant increase in the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in the testis of the 1.29 mGy/h and 3.46 mGy/h groups compared to the sham group (p < 0.05;

Figure 5B).

The comet assay further confirmed the presence of DNA strand breaks, indicative of radiation-induced genotoxicity. Specifically, the 3.46 mGy/h group demonstrated a significant increase in DNA damage compared to the sham and 0.39 mGy/h groups (

p < 0.05;

Figure 5C,D). These findings suggest that exposure to 3.46 mGy/h LDR radiation induces both apoptotic and non-apoptotic forms of DNA damage in testicular tissue.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the detrimental effects of cumulative LDR radiation exposure on testicular and epididymal structures in a dose-dependent manner in mice. Different oxidative stress markers, apoptosis, and fibrosis exhibited distinct threshold effects depending on the radiation dose.

Our study showed no significant differences in body weight among the groups (sham, 0.39, 1.29, and 3.46 mGy/h), indicating that radiation exposure under these conditions does not affect overall body mass. Similarly, testis weight showed no significant differences, although a slight trend toward reduction was observed in LDR radiation-exposed groups. However, the absence of a gross body or testis weight changes does not preclude the presence of histological or molecular alterations, which were further examined in subsequent analyses. Subtle yet biologically significant effects—such as oxidative stress, apoptosis, and fibrosis—may still occur, as revealed by histological and molecular analyses conducted in subsequent sections.

A significant increase in ROS levels was observed exclusively in the 3.46 mGy/h group, suggesting that oxidative stress may only reach a critical threshold at higher cumulative radiation doses. This aligns with previous studies indicating that oxidative stress responses often require prolonged or high-intensity stimulation to become detectable. Several reports have demonstrated dose- and time-dependent accumulation of ROS and mitochondrial dysfunction following LDR radiation expouse [

13,

14]. While the dose rates of irradiation vary across studies, our study employed one of the lowest LDR conditions reported to date. Despite this low exposure level, ROS levels were markedly elevated, indicating that even minimal LDR radiation can induce significant oxidative stress in testicular tissue. ROS plays a central role in radiation-induced tissue damage by promoting DNA strand breaks, lipid peroxidation, and cellular senescence, ultimately leading to fibrotic remodeling [

9,

15]. The absence of significant ROS elevation in the 0.39 mGy/h and 1.29 mGy/h groups suggests that compensatory antioxidant mechanisms may be sufficient to mitigate oxidative stress at lower doses. However, once the radiation dose exceeds a critical level, as seen in the 3.46 mGy/h group, these defense mechanisms may be overwhelmed, leading to excessive ROS accumulation and downstream pathological changes [

16].

Spermatogonial cell depletion was also observed only in the 3.46 mGy/h group. This suggests that spermatogenic cells, which are highly proliferative and radiation-sensitive, may initially withstand lower doses of radiation but undergo significant apoptosis and depletion at higher doses. This finding is consistent with reports that spermatogonial cells exhibit a dose-dependent sensitivity to radiation, with higher doses leading to impaired spermatogenesis and potential long-term infertility [

17,

18]. Similarly, SMA, a marker of myofibroblast activation, was significantly increased only in the 3.46 mGy/h group. Myofibroblast activation is a key feature of fibrosis, contributing to excessive ECM production and collagen deposition [

19]. Fibrosis-related genes and myofibroblast activation are responsive to elevated ROS and mitochondrial dysfunction [

20].

Collagen deposition was observed in all radiation-exposed groups (0.39, 1.26, and 3.46 mGy/h), suggesting that fibrotic changes can be initiated at even low radiation doses, potentially via sub-threshold oxidative injury or inflammation [

21]. This suggests that while oxidative stress and apoptosis may require a higher threshold of radiation exposure, collagen deposition occurs as a cumulative effect of radiation-induced tissue remodeling. Previous studies have suggested that LDR may activate fibroblasts and enhance ECM production through chronic inflammation and subtle tissue injury, even without widespread apoptosis or oxidative stress [

22]. The widespread collagen accumulation across all radiation-exposed groups highlights the long-term fibrotic potential of LDR radiation, reinforcing concerns about cumulative radiation exposure in occupational and environmental settings.

Interestingly, while the 1.29 and 3.46 mGy/h groups showed a significant increase in TUNEL-positive cells compared to the sham group, only the 3.46 mGy/h group exhibited significantly elevated DNA strand breaks in the comet assay. This highlights the complementary roles of the two assays: TUNEL detects apoptotic DNA fragmentation, while the comet assay is more sensitive to early genotoxic stress [

23]. The restriction of comet assay sensitivity to the highest dose suggests that genotoxic stress becomes prominent only above a certain threshold, whereas apoptosis may initiate at lower exposures. The detection of TUNEL-positive cells in the 1.29 and 3.46 mGy/h groups, but not at 0.39 mGy/h, indicates a dose-dependent activation of cell death pathways. Apoptosis at 1.29 mGy/h may reflect early tissue remodeling, while the more pronounced response at 3.46 mGy/h likely contributes to spermatogenic failure and fibrotic progression.

These findings illustrate the complex, dose-dependent effects of LDR radiation on testicular tissue. Collagen deposition was evident across all exposure levels, suggesting it may be an early or general response to radiation. In contrast, oxidative stress, spermatogonial cell depletion, and myofibroblast activation were predominantly observed at higher doses, indicating a threshold effect for more severe tissue alterations. The presence of apoptosis in the 1.29 and 3.46 mGy/h groups implies that moderate radiation doses can activate cell death pathways, whereas lower doses may initiate fibrotic remodeling without overt apoptosis. This pattern suggests that environmental exposure to low-level radiation may not cause immediate cytotoxicity but could promote progressive tissue remodeling and functional impairment over time. Although collagen accumulation occurred in all irradiated groups, a significant increase in ROS levels was detected only in the 3.46 mGy/h group. This implies that elevated ROS may be a more specific and mechanistically relevant marker of fibrotic progression than collagen content alone. The strong association between ROS elevation and upregulation of fibrotic genes such as α-SMA and PDGFRα further supports a central role for oxidative stress in driving LDR-induced testicular fibrosis.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that long-term exposure to LDR radiation at levels comparable to environmental conditions can dose-dependently induce testicular fibrosis and cellular damage. Notably, oxidative stress emerged as a pivotal factor in this process, with significantly elevated ROS levels—particularly at higher doses—correlating with fibrotic gene expression and apoptotic activity. While collagen deposition was observed even at the lowest dose (0.39 mGy/h), the selective increase in ROS at higher exposures highlights its mechanistic role in driving more severe pathological outcomes. These findings raise significant concerns about the cumulative impact of chronic radiation exposure and underscore the need for deeper investigation into ROS-mediated reproductive toxicity, particularly in populations with long-term ecological or occupational radiation exposure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.K. and D.K.; methodology, E.-J.K., A.H.P., J.H., D.G.K., J.Y., J.-M.K., B.A., and D.K.; software, E.-J.K. and D.K.; validation, E.-J.K. and D.K. formal analysis, S.K. and E.-J.K; investigation, E.-J.K., A.H.P., J.H., D.G.K., J.Y., J.-M.K., B.A., and D.K.; data curation, J.Y. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K..; visualization, E.-J.K., D.L.C., B.H.L. and D.K.; supervision, D.K.; project administration, E.-J.K.; funding acquisition, S.P.Y., J.S.K., and D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (#RS-2023-00219399 and #RS-2024-00454609) and the Glocal University 30 Project Fund of Gyeongsang National University in 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Chonnam National University Animal Care and Use Committee (approval no. CNU IACUC-YB-2024-172) on Nov 18, 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author (D.K.). The article includes all relevant data supporting this study’s conclusions.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the Dongnam Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences for their support in conducting the radiation exposure experiments. This work was supported by the Korea Basic Science Institute (National research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00403763 to Dr. Jinsung Yang)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the study’s design, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, in writing the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LDR |

Low-Dose-Rate |

| PDGFR |

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SMA |

Smooth Muscle Actin |

References

- Hall, E.J. Weiss lecture. The dose-rate factor in radiation biology. Int J Radiat Biol 1991, 59, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaie-Joniani, H.; Eriksson, D.; Sheikholvaezin, A.; Johansson, A.; Lofroth, P.O.; Johansson, L.; Stigbrand, T. Apoptosis induced by low-dose and low-dose-rate radiation. Cancer 2002, 94, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjemian, S.; Oltean, T.; Martens, S.; Wiernicki, B.; Goossens, V.; Vanden Berghe, T.; Cappe, B.; Ladik, M.; Riquet, F.B.; Heyndrickx, L.; et al. Ionizing radiation results in a mixture of cellular outcomes including mitotic catastrophe, senescence, methuosis, and iron-dependent cell death. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, E.J.; Shin, I.S.; Son, T.G.; Yang, K.; Heo, K.; Kim, J.S. Low-dose-rate radiation exposure leads to testicular damage with decreases in DNMT1 and HDAC1 in the murine testis. J Radiat Res 2014, 55, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, S.J.; Shalet, S.M. Spermatogenesis after cancer treatment: damage and recovery. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2005, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, G.T.; Stern, K. Reproductive aspects of cancer treatment: an update. Med J Aust 1999, 170, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, I.; Takahashi-Suzuki, N.; Kuroda, S.; Kumagai, K.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Anderson, D.; Satoh, T.; Yamashiro, H.; Miura, T.; Yamauchi, K.; et al. Effects of low-dose rate radiation on immune and epigenetic regulation of the mouse testes. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2024, 200, 1620–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Liu, Z.; He, Y. Radiation-induced fibrosis: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies from an immune microenvironment perspective. Immunology 2024, 172, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xu, C.; Song, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, S. Tissue fibrosis induced by radiotherapy: current understanding of the molecular mechanisms, diagnosis and therapeutic advances. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hu, P.; Chen, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H. Testicular fibrosis pathology, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment: A perspective on related diseases. Andrology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Bae, M.J.; Kang, M.K.; Kim, H.; Kang, Y.R.; Jo, W.S.; Lee, C.G.; Jung, B.; Lee, J.; Moon, C.; et al. Possible association of G6PC2 and MUC6 induced by low-dose-rate irradiation in mouse intestine with inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Med Rep 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siregar, A.S.; Nyiramana, M.M.; Kim, E.-J.; Shin, E.-J.; Kim, C.-W.; Lee, D.; Hong, S.-G.; Han, J.; Kang, D. TRPV1 Is Associated with Testicular Apoptosis in Mice. J Anim Reprod Biotechnol 2019, 34, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulms, D.; Zeise, E.; Poppelmann, B.; Schwarz, T. DNA damage, death receptor activation and reactive oxygen species contribute to ultraviolet radiation-induced apoptosis in an essential and independent way. Oncogene 2002, 21, 5844–5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Gong, P.S.; Zhao, H.G.; Bi, Y.J.; Zhao, G.; Gong, S.L.; Wang, Z.C. Mitochondrial modulation of apoptosis induced by low-dose radiation in mouse testicular cells. Biomed Environ Sci 2013, 26, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, W.; Lin, C.; Gong, S.; Li, C.; Wang, G.; Cai, L. Repetitive exposures to low-dose X-rays attenuate testicular apoptotic cell death in streptozotocin-induced diabetes rats. Toxicol Lett 2010, 192, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Parmar, J.; Verma, P.; Goyal, P.K. Radiation induced oxidative stress and its toxicity in testes of mice and their prevention by Tinospora cordifolia extract. Journal of Reproductive Health and Medicine 2015, 1, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakici, S.Y.; Irfan, G.A.; Levent, T.; Hatice, S.N.; and Mercantepe, T. Pelvic Radiation-Induced Testicular Damage: An Experimental Study at 1 Gray. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine 2020, 66, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmoonfar, R.; Mirzaei, F.; Najafi, M.; Varkeshi, M.; Ghazikhanlousani, K.; Momeni, S.; Saber, K. Radiation-induced Testicular Damage in Mice: Protective Effects of Apigenin Revealed by Histopathological Evaluation. Curr Radiopharm 2024, 17, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, A.; Abraham, D.J. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J 2004, 18, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.A.; Karam, H.M.; Shaaban, E.A.; Safar, M.M.; El-Yamany, M.F. MitoQ ameliorates testicular damage induced by gamma irradiation in rats: Modulation of mitochondrial apoptosis and steroidogenesis. Life Sciences 2019, 232, 116655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ye, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, Q.; Su, M.; Sun, S.; Xu, W.; Fu, Q.; Wang, A.; Hu, S. Low-Dose Ionizing Radiation and Male Reproductive Immunity: Elucidating Subtle Modulations and Long-Term Health Implications. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, L.; Stalfort, J.; Barker, T.H.; Abebayehu, D. The interplay of fibroblasts, the extracellular matrix, and inflammation in scar formation. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Shen, S.; Wang, D.; Ye, J.; Song, S.; Wang, Z.; Yue, Z. The role of HIF-1α-mediated autophagy in ionizing radiation-induced testicular injury. Journal of Molecular Histology 2023, 54, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).