3.2. Dissociation (Recombination) Process

In the description of the process

B→ (

a,

b) we isolate the vector representing the internal state of the boson from the “external” part depending on the spacetime coordinates and the spin. The latter, which is essentially a four-potential vector (spin 1) or, in the case of the Higgs boson only, a scalar doublet, is not influenced by the dynamics we are defining and will therefore not be further considered here. To characterize the internal boson dynamics, we associate the non-dissociated bosonic state

B and the pair of de Sitter spaces (

a,

b) to the two components of a column vector:

The dynamics operating at the interaction vertex leads to a superposition of these two vectors and the evolution parameter

ζ has no relation to the spacetime coordinates (in such coordinates the vertex

Bxy, where

x and

y are the external flavors concurrent at the interaction vertex, is a single point-event). The situation here is similar to that of the decay of a radioactive nucleus, whose quantum state is expressed by the superposition of the “decayed” and “non-decayed” states. These states correspond respectively to the second and the first vector of (97). These two vectors are the eigenvectors of the Hamiltonian operator:

with eigenvalues

MBc2 and (

Ma +

Mb)

c2 respectively. Here

MB,

Ma and

Mb are the rest masses of the boson, the fermion of flavour

a and the fermion of flavour

b respectively. They are the masses exchanged with the external fermionic lines (i.e., the masses supplied to the boson by the fermions with which it couples or given to them by the boson). The complete Hamiltonian operator is:

The evolution described by the Hamiltonian (99) occurs in an internal parameter

ζ, with:

where

x and

y are the external flavors concurrent at the interaction vertex; furthermore:

Here

qa,

qb are the charges respectively associated with the fermionic flavors

a,

b and the real variable

A (positive, negative or zero) is the action exchanged between the bosonic field and the fermionic field. In each single virtual dissociation/recombination process

B → (

a,

b), (

a,

b) →

B this action is distributed with mean 0 and variance

ħ by virtue of the uncertainty principle. By the central limit theorem, the total action

A is distributed according to a density:

The uncertainty Δ

A of

A involved in the creation/reabsorption of

qa,

qb is

q2/

c. By the uncertainty principle, the event can be real only if

A =

h/2; this justifies (102). In essence, (100)-(103) describe a condition on the variance of the squared charge at the interaction vertex, requiring that it be large enough to include the squared charges of

a and

b. Only under this condition, in fact, can the dissociation of

B into the pair (

a,

b) occur. The equation of motion is:

with initial condition |

ψ 〉

ζ = 0 = |

B 〉. It can be verified that, by setting:

one has:

We therefore have a quantum superposition of the two states (97). This superposition is generated by the coupling of

B with the external flavors which, for (101), are the same as the elements of the pair (

a,

b). Here

φ/2

π = (

Ma +

Mb)

c2ζ/

h ≤ ½. For

φ = 0, Eq.(107) is reduced to the boson

B only; it is reduced to the spaces

a,

b for

φ =

φmax =

π, and it is in this condition that the coupling with the external fermions occurs. The transition amplitude between the “instants”

ζ = 0 and

ζ =

ζmax=

h/2(

Ma +

Mb)

c2 is given by (

S = evolution operator):

Recall that fermions are stationary states, harmonic solutions of the WdW:

where

k =

a,

b is the index of the fermionic flavor and

rk is the de Sitter radius corresponding to that flavor.

It should be noted that the squared modulus of (108) does not provide the probability of reaction, because the factor associated with the Gaussian distribution (104) is missing. However, it is easily verified that this factor is a function of

qa,

qb which do not depend on the generation. Therefore it is not relevant in the mixing phenomenon, while it is relevant in the definition of the coupling constant, as will be shown in a subsequent subsection.The action of the

B boson in the interaction vertex is schematized by the operator:

where the summation is restricted to the flavor indices

i,

j allowed for

B. If

B is associated to the field four-potential

Aμ(

x), where

x is the current point-event of Minkowski spacetime, its action at the interaction vertex is specified by

γμAμ(

x)

. Defining the amplitudes of the external fermions of flavors

a and

b as |

ϕl 〉

ψ(

x) and

, respectively, and introducing the coupling constant

Q, one immediately obtains the vertex amplitude of the conventional QFT (including flavor mixing):

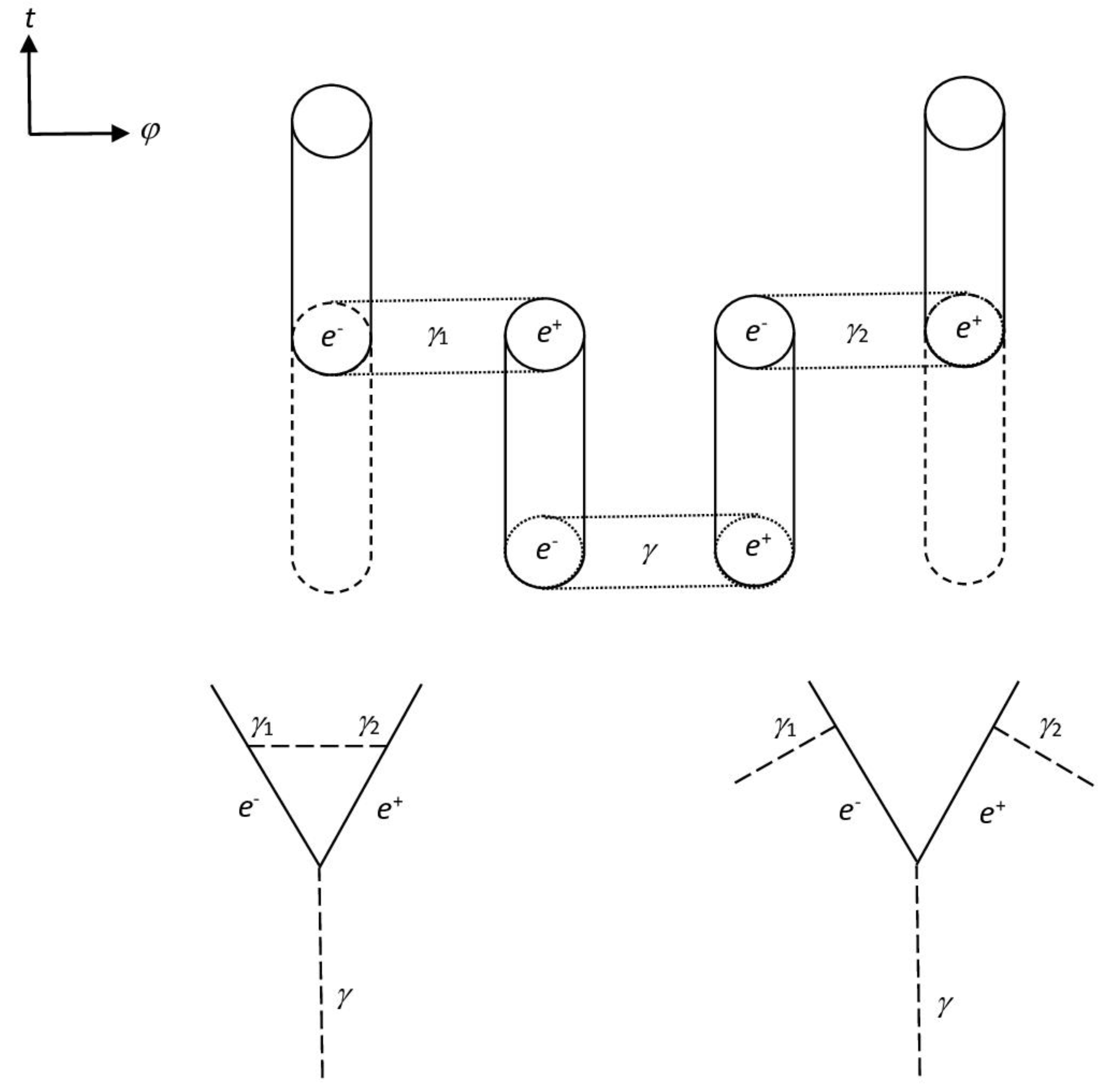

3.3. Diagrams

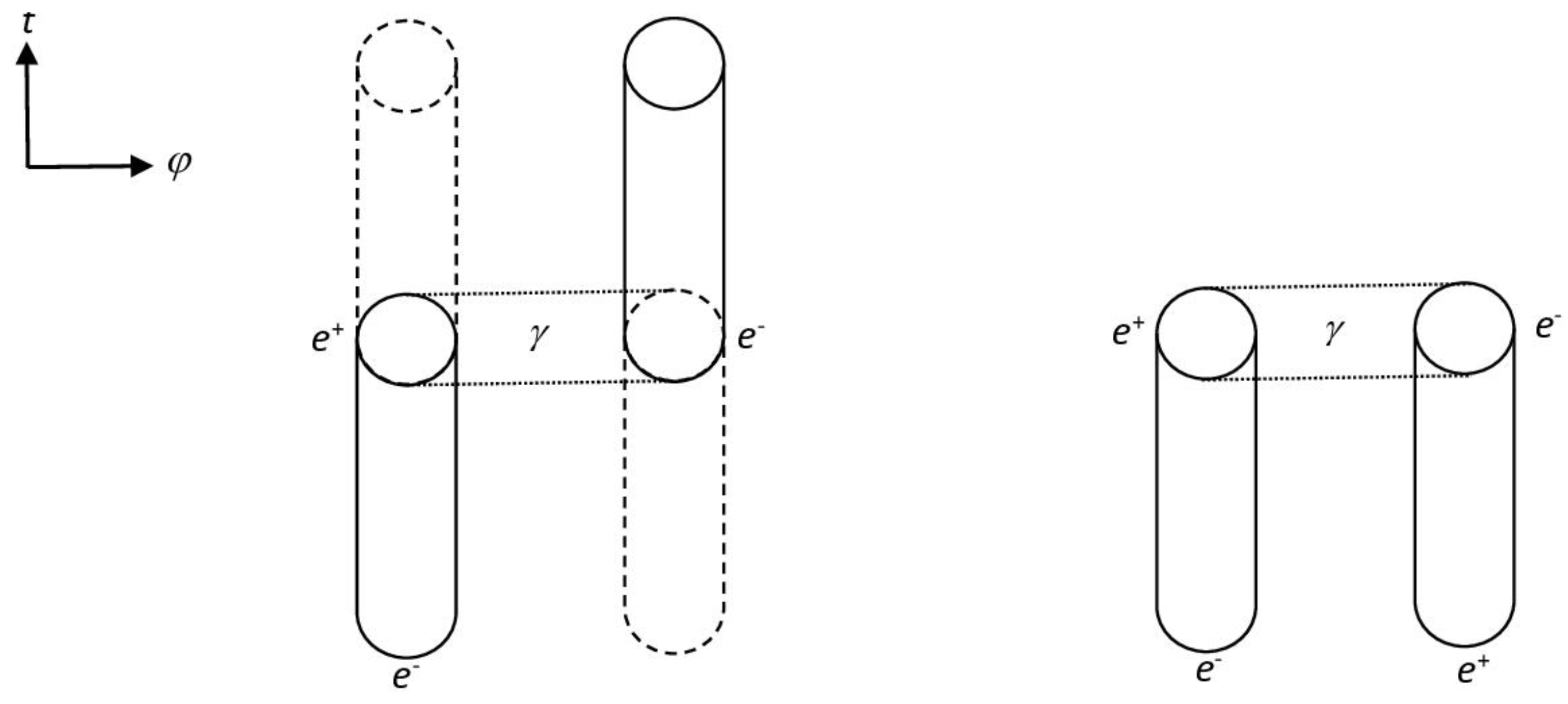

The process described in the previous Section can be illustrated graphically with appropriate diagrams. Below we propose some of them concerning the photon-electron (positron) coupling. The corresponding Feynman diagrams are shown for comparison.

Figure 1.

a) Absorption or emission of a photon by an electron (real process): the two processes are distinguished by the sign of the energy difference between the outgoing electron and the incoming electron; by exchanging electrons and positrons in the figure, the absorption or emission of the photon by a positron is obtained. b) Annihilation of an electron-positron pair (virtual process); by reversing the process around the horizontal axis, the analogous diagram for thecreation of a pair is obtained. The t-axis is time. The pairs generated by the dissociation of the photon are enclosed in horizontal tubes with dotted lines. The tubes delimited by continuous lines represent the states that evolve in t, those delimited by broken lines represent evanescent states associated with QJs. The elements of a given pair appear as separate for illustrative purpose only.

Figure 1.

a) Absorption or emission of a photon by an electron (real process): the two processes are distinguished by the sign of the energy difference between the outgoing electron and the incoming electron; by exchanging electrons and positrons in the figure, the absorption or emission of the photon by a positron is obtained. b) Annihilation of an electron-positron pair (virtual process); by reversing the process around the horizontal axis, the analogous diagram for thecreation of a pair is obtained. The t-axis is time. The pairs generated by the dissociation of the photon are enclosed in horizontal tubes with dotted lines. The tubes delimited by continuous lines represent the states that evolve in t, those delimited by broken lines represent evanescent states associated with QJs. The elements of a given pair appear as separate for illustrative purpose only.

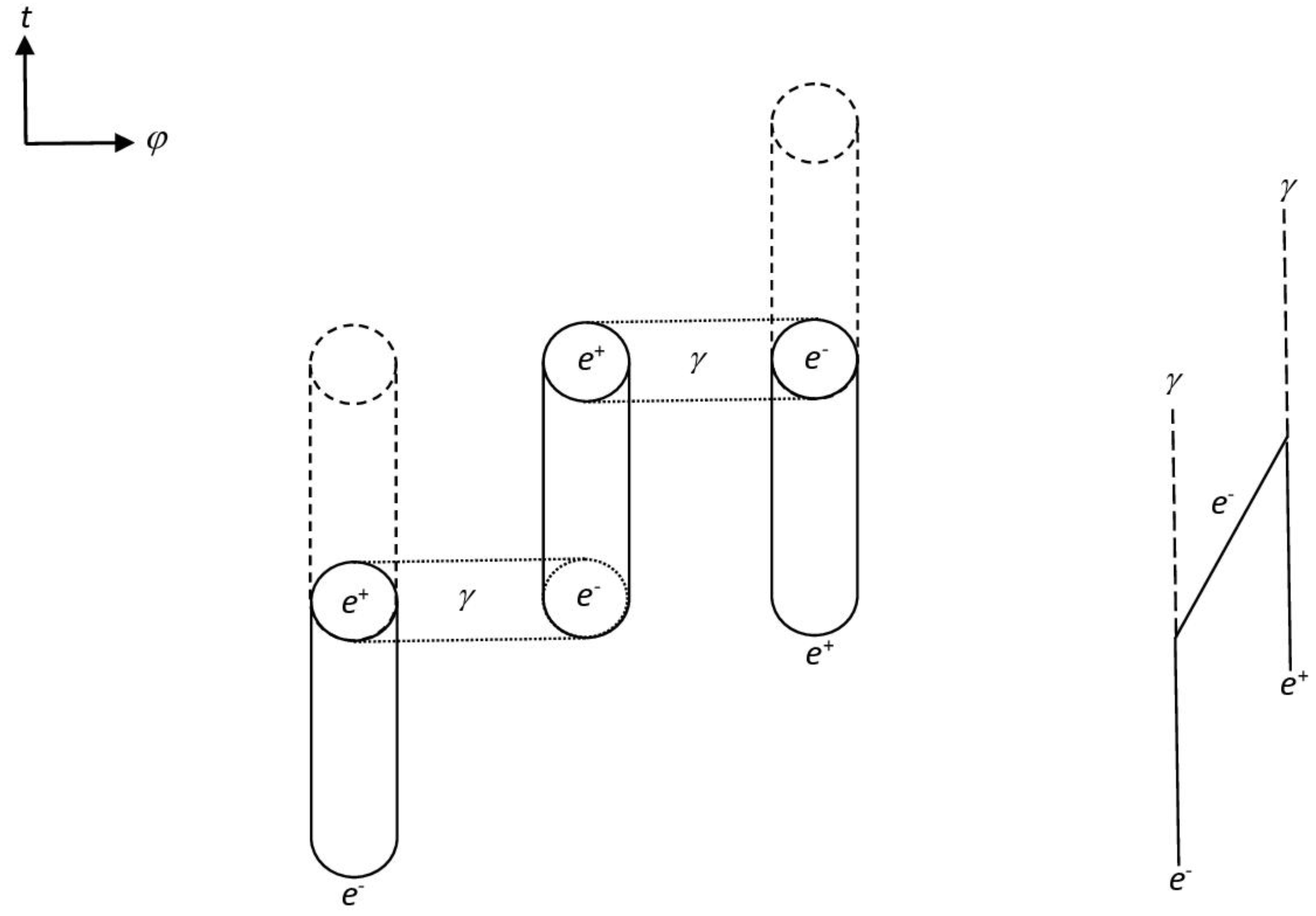

Figure 2.

Decay of positronium into two photons (real process). On the right is the corresponding Feynman diagram, in which the horizontal variable is space. Note that while the internal fermionic line is not connected to evanescent states (due to QJs), the external fermionic lines are.

Figure 2.

Decay of positronium into two photons (real process). On the right is the corresponding Feynman diagram, in which the horizontal variable is space. Note that while the internal fermionic line is not connected to evanescent states (due to QJs), the external fermionic lines are.

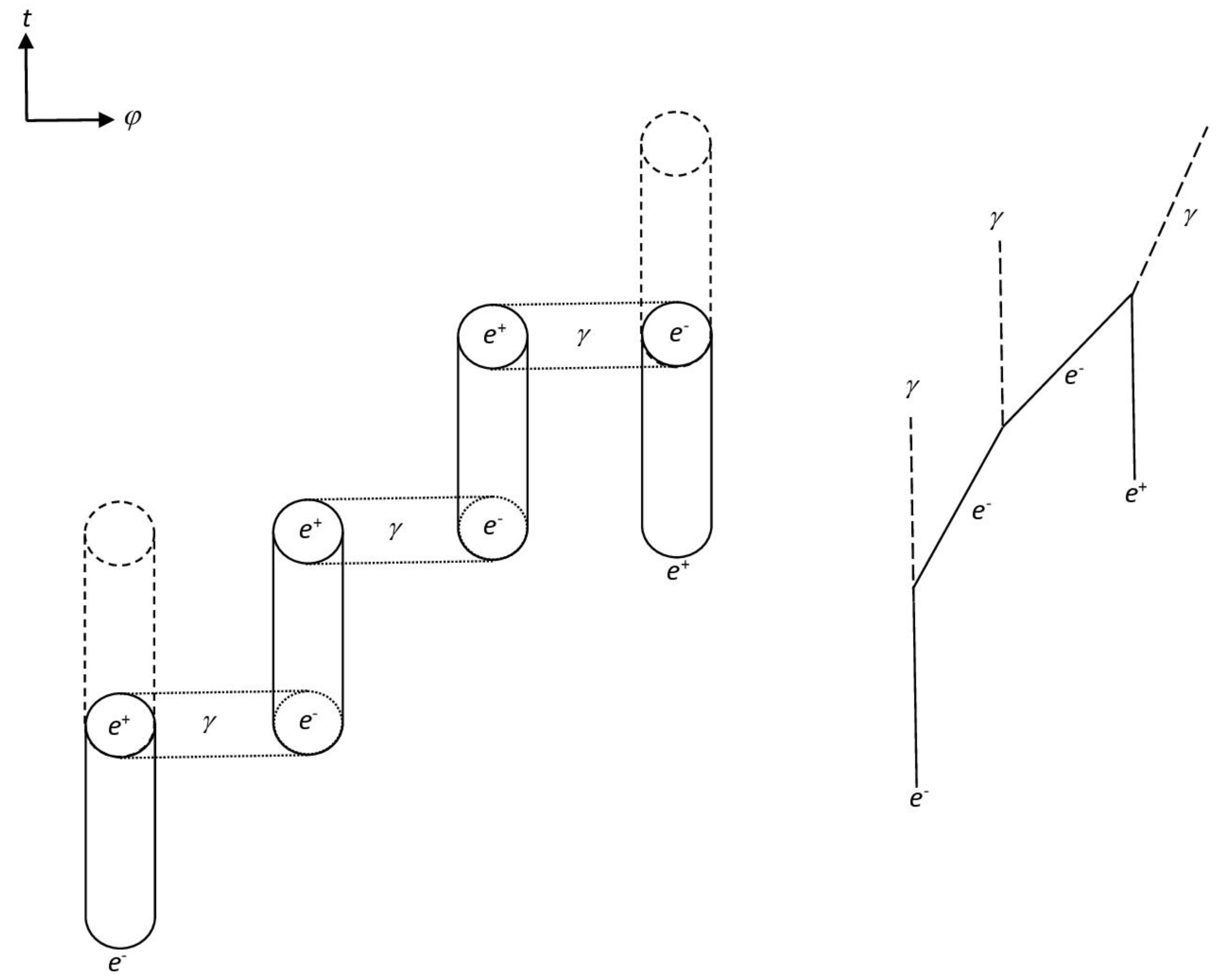

Figure 3.

Decay of positronium into three photons (real process). On the right is the corresponding Feynman diagram, in which the horizontal variable is space. Note that while the internal fermionic lines are not connected to evanescent states (due to QJs), the external fermionic lines are.

Figure 3.

Decay of positronium into three photons (real process). On the right is the corresponding Feynman diagram, in which the horizontal variable is space. Note that while the internal fermionic lines are not connected to evanescent states (due to QJs), the external fermionic lines are.

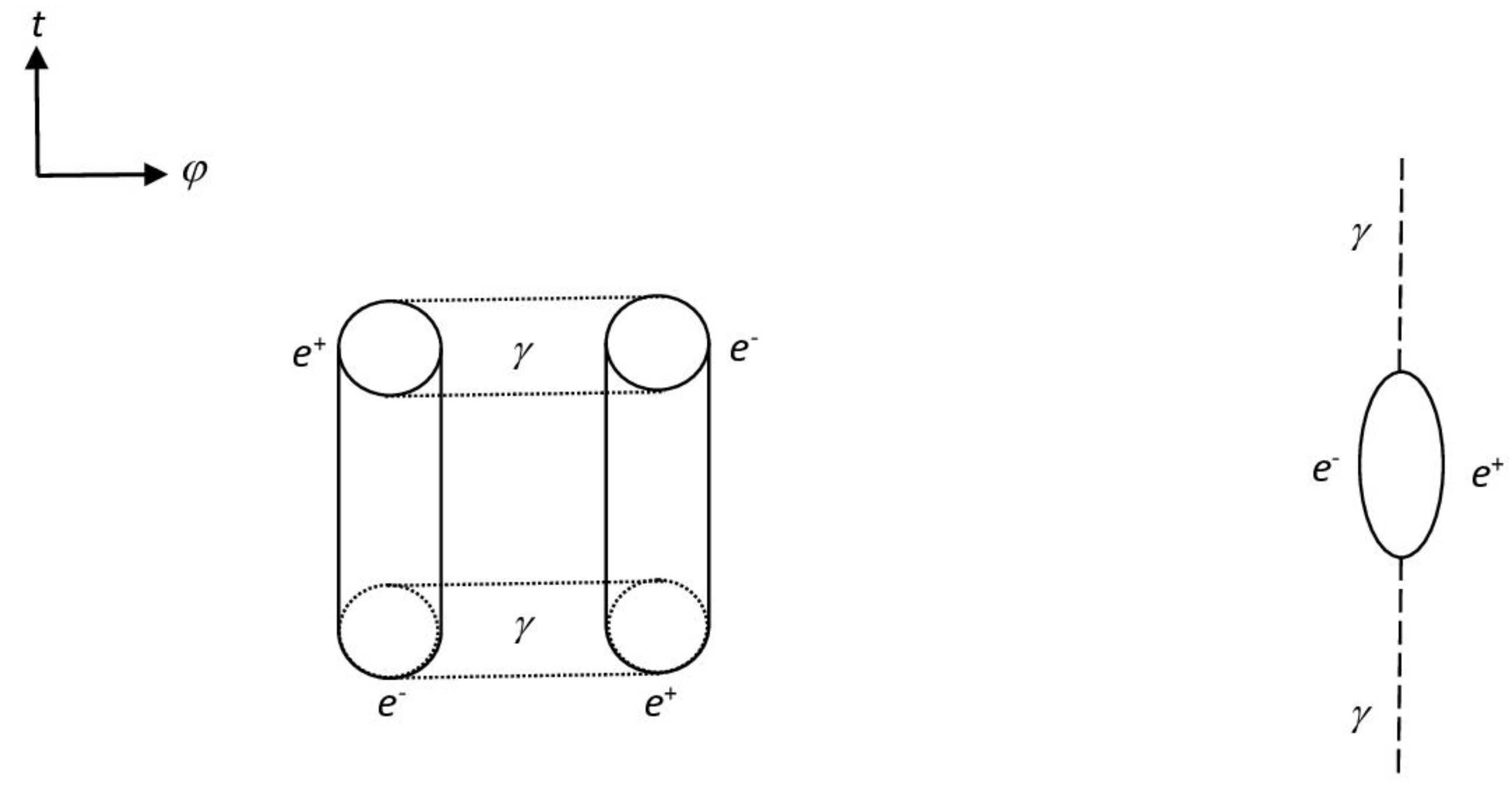

Figure 4.

Photon dissociation (virtual process). The corresponding Feynman diagram is shown on the right, where the horizontal variable is space. The fermionic lines, being internal, are not connected to evanescent states.

Figure 4.

Photon dissociation (virtual process). The corresponding Feynman diagram is shown on the right, where the horizontal variable is space. The fermionic lines, being internal, are not connected to evanescent states.

Figure 5.

Two processes represented by the same state connection diagram, but by different Feynman diagrams, respectively in the case in which γ1 and γ2 are the extremes of the same photon line (left) or not (right).

Figure 5.

Two processes represented by the same state connection diagram, but by different Feynman diagrams, respectively in the case in which γ1 and γ2 are the extremes of the same photon line (left) or not (right).

3.4. A Hypothesis on the Meaning of the De Vries Formula

We now want to show how a purely empirical formula proposed many years ago to express the renormalized fine structure constant can be interpreted in the present conceptual framework. We therefore specialize in the particular case in which the gauge boson

B is the photon. To fix the ideas, we can make the identification, however not essential, (

a,

b) = (

e+,

e-). As we have seen, the interaction is subordinate to the condition

A =

h/2 ±

q2/

c, where

A is a random variable whose density is expressed by (104). The coupling constant must therefore contain the ratio between the probability of this fluctuation and the probability of a fluctuation of equal amplitude in the vacuum (

A = 0):

Since the flavors a and b are identical to the flavors of the afferent fermions at the vertex by virtue of (101), and therefore the de Sitter radii of a and b are fixed by the conditions external to the vertex, the exchange of squared charge between a (b) and x (y) determines an exchange of mass by effect of (36). This exchange will be oriented: a will yield mass to x or vice versa, and the same will happen for b and y.

Since the charges of the two fermions

a,

b are equal in modulus and opposite in sign, the two exchange processes will be symmetric. Since

q2 is the total squared charge exchanged, each of the two fermions will exchange a squared charge equal to

q2/2. The exchange of action implied in each of these two charge exchanges will be

q2/2

c. From Eq.(101), the total exchange of action in the dissociation process is

h/2; thecoupling constant of the single element of the pair (

a or

b) is therefore:

Let us now consider the exchange of squared charge between

a and

x, or between

b and

y. In each of the two cases, the

q2/2

π factor in (113) represents the squared charge transferred from one of the two fermions (let's say fermion 1) to the other. We will therefore indicate this quantity as

q21 → 2. Fermion 2 will return a share

q22→ 1 =

q21 → 2/2

π of squared charge to fermion 1, again in accordance with expression (113) which is symmetric with respect to the direction of the exchange. The process is clearly iterative and we can set:

where

i is the iteration index. Eq.(114) can be written in the form:

This means that at the

i-th iteration the coupling constant is

α/(2

π)

i. The contribution of the

i-th iteration to the overall coupling constant of the whole sequence of iterations is given by the product of

α/(2

π)

i by the total contribution of the previous iterations. That is:

α(

i + 1) =

α(

i)

α/(2

π)

i, where

i = 0, 1, 2, 3... and

α(0) = 1. We then have

α(1) =

α(0)

α/(2

π)

0 =

α, as is natural;

α(2) =

α(1)

α/(2

π)

1 =

α2/2

π ;

α(3) =

α(2)

α/(2

π)

2 =

α3/(2

π)

3;

α(4) =

α(3)

α/(2

π)

3 =

α4/(2

π)

6, and so on. For each of the two sequences of iterations relating respectively to the exchanges between

a and

x, and between

b and

y, we therefore have a total coupling constant defined by the series:

The first term is related to the absence of exchanges between a and x (or between b and y), and it represents the total squared charge hc/2 not yet exchanged, but available in the process B→ (a, b) [Eq.(101)].

The overall coupling constant is therefore the product of the two functions Γ(

α), associated respectively with the two sequences, and the factor exp(-

π2/2), that is

α' = [Γ(

α)]

2exp(-

π2/2). This must therefore be the coupling constant of the photon to the charged fermion. But this constant must equate

α. We therefore have

α' =

α and hence:

This relation defines the value of

α. It was proposed, without any physical justification, by Hans De Vries more than twenty years ago [

36]. We note that if

z is the charge

qf of the fermion with which the photon couples, expressed in units

e, i.e.

z =

qf/

e, the Eq.(117) actually does not give

α but

α/

z2. That is:

as it should be. However, in common usage

α is defined as 1/137,... and the coupling constant then becomes:

z2α =

z2/137,... .

The Eq.(117) can be solved iteratively by assigning an initial value to

α and inserting it in the right-hand side, then substituting the value thus obtained again in the right-hand side and so on. The obtained value and the experimental one are reported below [

37]:

CODATA 2018 (source: NIST): 7.297 352 5693(11) × 10-3

Hans de Vries: 7.297 352 5686 × 10-3

We must however point out that the CODATA 2022 adjustment differs from the computed result by 4 standard deviations (new recommended figure: 7.297 352 5643(11) × 10

-3) [

38].

3.5. Mixing Matrices

Eq.(111) is inclusive of flavour mixing. We now want to investigate this phenomenon in the context of the present model. Let us consider the dissociation B → of a gauge boson B into two fermions of flavour a, b and charge q1, -q2 respectively. If B is self-conjugated, the self-conjugation property must extend to the pair (); this is only possible if a = b and q1 = q2. This is the situation for B = H0, γ, Z0, graviton; hence the interactions of these bosons do not exhibit flavour mixing. In the case of gluons, the exchange of flavours a, b in the quark-antiquark pair () is equivalent to a charge conjugation. But the exchange of flavors cannot induce a modification of the color charge, given the ontological independence of color from flavor. This contradiction can be resolved only by imposing the equality a = b of flavors and therefore the absence of flavor mixing in interactions mediated by gluons. This leaves only the case of the W boson mediating weak interactions with charged currents. As in the gluonic case, the exchange of flavors a, b inverts the charge of the W. But, unlike the gluonic case, the electric charge is not ontologically independent of flavor; on the contrary, it is a function of it. Therefore there are no a priori reasons to assume the absence of flavor mixing in interactions mediated by the W.

Let us consider a virtual interaction vertex in which a W could couple with two fermions, one of generation ia, the other of generation ib. A fermion of generation ia (ib) would then enter this vertex and a fermion of generation ib (ia) would exit it. If we fix the difference n = | ia – ib |, there will be n + 1 possible entering states and the same number of exiting states, and therefore N = (n +1)2 distinct modes of coupling between entry and exit. If we assign an arbitrary direction to each coupling, there will therefore be N2 distinct pairs of couplings of opposite direction or “loops”. The real dissociation of the W, induced by the external fermionic lines of flavor a, b, selects one of these loops, consisting respectively of the coupling a → b (b → a) and the coupling b → a (a → b). A loop on N2 is thus selected, which implies that the vertex amplitude is weighted by a factor 1/N. From now on we will consider the case of a real dissociation B → .

We must now construct the vertex amplitude (except for the factor constituted by the coupling constant, independent of

a and

b, which does not interest us here). The first factor that enters into this amplitude is clearly the product of the phase factors of the fermions originating from the dissociation of the

W, which we will write:

Here

ma,

mb are the masses of the fermions of flavor

a,

b with which the

W couples at the considered vertex; the time interval

h/

MWc2, where

MW is the mass of the

W, is the renormalization time scale of the

W. A subsequent factor will contain the Wick-rotated versions of the wave functions of the outer fermions [Eqs. (46),(47)]:

The larger masses are considered to be incoming [with this choice, the action (incoming mass – outgoing mass)

c2 ×

ħ/

Mwc2 is positive and corresponds to the exponent in (120)]. The constants

C of the exponentials in

ξa,b [Eq. (47)] have been assumed equal to 1, in accordance with what was established in

Section 2.5. In accordance with the reasoning given at the end of

Section 2.3, we then set

ξa,b =

r/

ra,b =

c|

t |/

ra,b, where the variable

r has the dimensions of a length and therefore the variable

t has the dimensions of a time;

ra,

rb are the de Sitter radii of the fermions of flavor

a,

b;

c is the limit speed. We will normalize the Wick-rotated wave functions

y =

Aexp(-

c|

t|/

rdS) according to the condition:

Integrating over the variable |

t | we have:

The integration is limited to positive values of the scalar field

ξ, which can be admitted if this variable is considered as an rms value of the field. The amplitude of the coupling vertex between the

W and the two fermions is then expressed by:

In the absence of mixing, we have a ≡ b and therefore, as can be easily seen, fab = δab; the vertex amplitude is then reduced to the coupling constant. In the case of W, however, f is neither the unit matrix nor a diagonal matrix, and the problem therefore arises of how it can be diagonalized. As can be seen, the matrix f is Hermitian, that is (fab)* = fba. Let us consider the matrix V that diagonalizes the matrix fab, that is, such that VfV-1 = Diag is diagonal. We immediately have (VfV-1)+ = (V-1)+f+(V)+ = (V-1)+f(V)+ = (Diag)+ = Diag = VfV-1, from which it follows that V is unitary. In the basis where f is diagonal, the W dissociates into one of three fermion-antifermion pairs. In the case of quarks these three pairs will be (d’, u), (s’, c), (b’, t) or (d, u’), (s, c’), (b, t’); in the following we will limit ourselves to the first case. The amplitudes d’, s’, b’are linear combinations of the amplitudes d, s, b and therefore there is flavor mixing. The matrix V is the mixing matrix. A similar reasoning applies to the dissociations of the W into leptonic a, b states (charged lepton and neutrino). The mixing matrix will be the CKM matrix for quarks, the PMNS matrix for leptons.

The relations presented in this section allow us to define the elements of the fa,b matrix for both quarks and leptons (we will assume that the de Sitter radius of a neutrino mass eigenstate is the same as that of the charged lepton of the same generation). The correctness of the reasoning is then verified if the mixing matrix constituted by the best fit of the experimental data diagonalizes the fa,b matrix for suitable choices of the fermion masses. Both the quark and neutrino masses are in fact known within experimental error bars, and the diagonalization will be better approximated by suitable choices of the values of these masses within the respective error bars. The situation is exposed in the next two subsections.

3.5.1. The CKM (Cabibbo-Kobayashi-Maskawa) Matrix

The calculation strategy is as follows. We start from the mixing matrix in the “standard” parametrization [

39]:

where

cij = cos(

θij),

sij = sin(

θij), (

i,

j) = 1, 2, 3. The matrix

V is therefore entirely determined by the angles

θij and the phase

δ13. For these parameters we assume the experimental best fit values [

39]:

θ12 = 13.04° ± 0.05° θ23 = 2.38° ± 0.06° θ13 = 0.201° ± 0.011° δ13 = 68.08° ± 4.5°

Running the quark masses on their experimental error bars [

40]:

mu = 1.9-2.6 MeV md = 3.5-5.5 MeV ms = 84-104 MeV

mc = 1.15-1.35 GeV mb = 4.2-4.4 GeV mt = 172 GeV (fixed)

we first compute the matrix fab, then the matrix VfV-1 = Diag, choosing the values of the masses that minimize the ratio between the sum of the moduli of the off-diagonal terms of Diag and the sum of the moduli of its diagonal terms. The lowest value of this ratio (0.0039) is obtained with the following masses:

mu= 1.97 MeV md = 3.5 MeV ms = 84 MeV

mc = 1.15 GeV mb = 4.2 GeV mt = 172 GeV (fixed)

The list of elements of Diag, defined up to a common factor, is as follows (for each element the real part is reported first, then the imaginary part):

Diag(1,1) = (9.907985479E-02, 4.445020854E-02)

Diag(1,2) = (-2.097622026E-03, 1.963231713E-03)

Diag(1,3) =(2.270226367E-03, -1.590122236E-03)

Diag(2,1) =(8.128318004E-04, 2.398663666E-03)

Diag(2,2) = (0.134869426, 4.873338714E-02)

Diag(2,3) =(-9.121133015E-03, 1.912320405E-02)

Diag(3,1) =(1.110927667E-03, -1.323248027E-03)

Diag(3,2) = (2.465872327E-03, -8.105657063E-03)

Diag(3,3) = (0.766050756, -9.318360686E-02)

These results are consistent with the proposal of this paper, that the mixing matrix V is the diagonalization matrix of the vertex amplitudes fab, obtained by postulating the dissociation of the gauge boson, induced by the act of interaction with the fermions with which it couples. The boson instead remains undissociated during its propagation.

3.5.2. The PMNS (Pontecorvo-Maki-Nakagawa-Sakata) Matrix

The procedure is the same as in the case of quarks. The matrix is considered in the same standard parametrization seen in the previous subsection, with the following parameter values [

41]:

θ12 = 33.41° + 0.75° - 0.72° θ23 = 49.1° + 1.0° -1.3° θ13 = 8.54° +42° - 25° δ13 = 197° + 42° - 25°

Precisely, the central value is taken. The variation of the parameters within their error bars is not considered, leaving this possibility to possible future investigations. The masses of the charged leptons are considered fixed, while those of the neutrino mass eigenstates are varied within reasonable error bars, according to the following scheme(compatible with PDG limits):

me = 0.511 MeV mμ = 105.658 MeV mτ = 1776 MeV

mν1 = 0.0001-0.0006 eV mν2 = 0.0001-0.001 eV mν3 = 0.0001-0.06 eV

The lowest value of the ratio of the sum of the moduli of the off-diagonal terms of Diag to the sum of the moduli of its diagonal terms (0.1257) is obtained with the following masses:

mν1 = 0.0006 eV mν2 = 0.001 eV mν3 = 0.06 eV

that is, practically the upper extremes of the adopted bars. The list of the corresponding Diag elements is the following:

Diag(1,1) = (0.318358690, 4.858494736E-03)

Diag(1,2) = (2.038531750E-02, 1.348413900E-02)

Diag(1,3) = (1.689680666E-02, -1.703028567E-02)

Diag(2,1) = (1.838763803E-02, 1.354285795E-02)

Diag(2,2) = (0.313012689, 7.760077715E-04)

Diag(2,3) = (-3.567337990E-04, 1.792673953E-02)

Diag(3,1) = (1.815088838E-02, -1.137212384E-02)

Diag(3,2) = (1.312024891E-03, 1.500429027E-02)

Diag(3,3) = (0.368628621, -5.634509027E-03)

It can therefore be stated that the calculation methodology illustrated in this Section also works in the case of leptonic couplings of the W boson. The results seem consistent with a direct mass hierarchy (although this point should be explored with more extensive numerical studies). In the calculation, the identity of the de Sitter radii of the states ν1, ν2, ν3, and of the charged states e, μ, τ, respectively, has been assumed.