1. Introduction

Vaccine efficacy remains an area of concern in vaccine science. Increasing evidence has shown that the microbiome modulates immune response [

1,

2,

3]. The co-development of the immune system and microbiome occurs during the first two years of life [

1,

4,

5]. Lack of microbial stimulation will lead to an underdeveloped immune system, as microbial stimuli drive key processes in the maturation of adaptive immune cells [

6,

7]. This interplay between gut microbiota and the immune system may partially account for variability in vaccine response.[

8,

9,

10,

11] In humans, specific bacterial taxa have been linked to variations in vaccine efficacy [

10,

11,

12], However, few studies have investigated the influence of the gut microbiome on the vaccine response, especially among adults [

3]. Actinobacteria were positively associated with adaptive immune responses to systemic vaccines like bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), tetanus toxoid (TT), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and the oral polio vaccine (OPV) in a study of Bangladeshi infants. Conversely, bacteria diversity and abundance of Enterobacteriales, Pseudomonadales, and Clostridiales were associated with lower vaccine response measured by vaccine-specific T-cell proliferation [

13].

The co-development of the gut microbiota and immune system makes it a beneficial mutualistic relationship, allowing the host to maintain a balance of active immunity to pathogens and vaccines [

2,

14]. Probiotics with specific strains have been shown to modulate the gut microbiome and systemic immune response and provide the basis for studies with vaccines in humans [

15,

16,

17]. Oral treatment with Clostridium bacteria was shown to promote the expansion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the intestines of early life mice, conferring resistance to colitis and augmented immune response in adulthood [

18]. A study using germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice demonstrated impaired antibody responses to influenza vaccines, which were restored by oral dosing of flagellated strain of E. coli [

19]. Results of microbiome modulation to boost vaccine response in humans has yielded mixed results in previous clinical trials, but shows potential for further study [

14,

20,

21,

22].

In low- and middle-income countries, intestinal dysbiosis is associated with environmental influences that can negatively impact vaccine efficacy, such as commonly occurring undernourishment and gastrointestinal infections [

2]. Schistosomiasis is a neglected tropical disease caused by infection with Schistosoma flatworms.

Schistosoma mansoni (

S. mansoni) infection is endemic in Uganda, with a national prevalence of 25.6% [

23]. Fishing communities have a particularly higher burden and socio-economic vulnerability to

S. mansoni infection, with approximately 51-57% of the population being infected despite door-to-door treatment campaigns [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Treatment consists of a single oral dose of praziquantel (PZQ).

S. mansoni infections impact the immune system and possibly enhance the virulence of hepatrophic viruses [

28]. While about half of schistosome eggs are carried through the bloodstream to the liver, the other half attach to the endothelium and migrate through the intestinal tissues. These eggs release a mixture of enzymes and antigens which promote the recruitment of immune cells, the development of inflammatory infiltrates, and the formation of tissue granulomas at the site of egg deposition within the intestinal wall [

29]. Multiple studies have shown that the resulting inflammation results in varied changes in the alpha and beta diversity of the host microbiome compared to uninfected controls, suggesting that there is likely a complex interplay between schistosomes, the gut microbiota, and the inflamed host immune system [

30].

Hepatitis B (Hep B), a life-threatening disease caused by HBV, is highly endemic in Uganda, with a national prevalence of approximately 4.3%. The burden is substantially higher burden (7%) among fishing communities compared to the global prevalence of 3.9% [

31]. Transmission occurs through mucosal or percutaneous exposure to infected blood or other body fluids [

32]. Over 80% of individuals with chronic HBV are unaware of their status, preventing them from accessing care and treatment interventions aimed at reducing transmission [

33]. Consequently, vaccination remains the most effective strategy for protecting populations against HBV. An estimated 52% of Ugandan adults remain infected with HBV despite Hep B vaccine incorporation in early childhood immunization programs [

32]. Although the Hep B vaccine is effective, 5-10% of individuals do not develop an immune response [

34,

35]. It has also been shown that Hep B infected individuals experience compositional changes in their gut microbiota relative to healthy controls [

36,

37].

Risk of both Hep B, and of

S. mansoni infection is high in Lake Victoria fishing communities [

31]. To better understand the relationship between

S. mansoni infection, the gut microbiome, and Hep B vaccination, we analyzed samples from a cohort of fisherfolk participants in Uganda who were part of a simulated vaccine efficacy trial (SiVET). In this trial, the ENGERIX-B Hep B vaccine, a well-established vaccine against hepatitis B, was administered to Hep B antigen-negative individuals. Participants from the fishing village had regular exposure to Schistosoma and likely exhibited higher than-average levels of worm burden. Individuals with low exposure to S. Mansoni were enrolled from a clinic in Kampala as controls. At the conclusion of the SiVET trial, we conducted a follow-up study to characterize the microbiomes of praziquantel-treated individuals at pre- and post-immunization time points, focusing on those with high and low serum worm burdens. Worm burden was quantified using a circulating anodic antigen (CAA) assay, which measures Schistosoma-derived antigens in the bloodstream. CAA levels serve as a direct indicator of living worm presence, reflecting ongoing infection and associated worm burden [

25]. The purpose of this study was to assess the association between S. mansoni infection status, gut microbiome, and Hep B vaccination responses, as well as understand how the baseline microbiome is associated with long-term Hep B vaccine efficacy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a prospective observational study, where participants were enrolled as part of a larger community-based simulated vaccine efficacy trial (SiVET) in Uganda. For this study, healthy adult males and non-pregnant females aged 18-49 were enrolled from two communities: a high S. mansoni-burdened fishing community (Kigungu) [

25], and a low S. mansoni burdened cohort from the Good Health for Women Project clinic in Kampala [

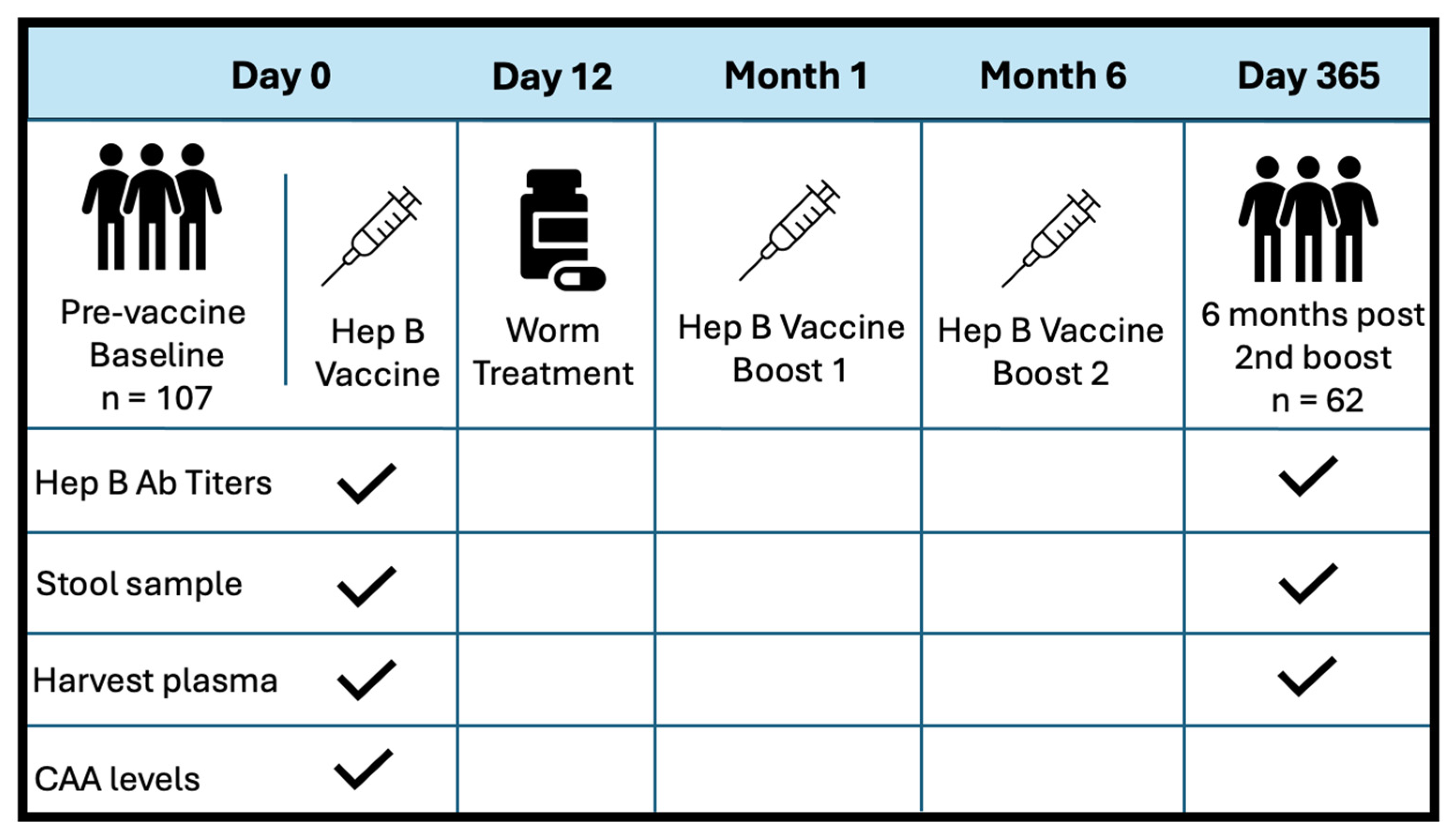

38]. Inclusion criteria for the study encompassed: negative Hep B surface antigen and core antibody tests, HIV-uninfected, capability for participation, willingness to provide written informed consent for the Hep B vaccine, and consent for 12-month follow-up after the first study immunization. Participants were not prescreened for active malaria or latent TB infections. Adults underwent screening up to six weeks prior to receiving the first dose of the Hepatitis B vaccine, ENGERIX-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). This was followed by two booster doses administered at months 1 and 6. Each dose was delivered intramuscularly into the deltoid muscle at 20ug/mL. Stool samples were collected at baseline, and six months post-all doses (one-year follow-up). S. Mansoni infection status was determined by inspection of participant stool samples for the presence of schistosome eggs. If stool samples were considered positive, patients were treated with 40 mg/kg body weight single dose (average 2.4 g) of Praziquantel (PZQ) on D12, following the first dose of Hep B vaccine.

Figure 1 illustrated the study design at baseline and exit. PBMCs and plasma were collected before vaccination at D0, and at one year follow-up (D365). Patient plasma was evaluated for serum schistosome-specific circulating anodic antigen (CAA), a quantitative biomarker of S. mansoni infection.

2.2. Circulating Anodic Antigen (CAA) Assay

Analysis to determine active S. mansoni infection was carried out at Day 0, prior to first vaccination, using frozen sera samples and techniques described previously [

25]. CAA concentration standards and serum negative controls were used to create a calibration curve to establish CAA cutoff levels and quantify samples. Participant samples were then evaluated using the SCAA500 diagnostic method with a detection threshold of 3pg/mL. Samples with insufficient serum volumes were evaluated using the SCAA20 test format, using 20 ul serum but a lower limit of detection at 30 pg/mL. CAA lateral flow strips were placed in wells containing 20ul of concentrated patient sample overnight and read the next day using an Upcon plate reader (Labrox Oy, Turku, Finland). Flow control signals (FC) of the individual strips were used to normalize the test line signals (T; relative fluorescent units, peak area) and the results were expressed as Ratio value (R = T/FC).

2.3. Hepatitis B Antibody Testing

Serum samples were assayed for HBV infection, to confirm Hep B-negative status prior to vaccination and to differentiate active infection from past exposures. At screening, samples were tested for three different markers: Hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg), Hep B core antibody (anti-HBc), and Hep B surface antibody (anti-HBs). Anti-HBs testing was performed using the Cobas e 411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), using a cut off value of 10IU/L. HbsAg was tested for using the VIDASHbsAgUltra kit, and the antiHBc antibodies were tested for using the VIDASanti-HBc Total II kit (Biomerieux SA, France), both on a MinVidas analyzer. During subsequent follow-up visits, only the anti-HBs antibody was assayed.

2.4. Microbiome Analysis Using 16S rRNA Sequencing

Extracted DNA was quantified with barcoded universal primers to amplify V4 hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA genes. PCR amplification will be purified, quantified and pooled prior to sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform using the 300 bp paired-end protocol [

39]. Sequence read quality will be assessed using a standardized bioinformatics pipeline, implemented in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Human Microbiome Project standard operating procedures [

40,

41,

42]. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) will be clustered according to the Greengenes database [

43,

44]. Taxonomy will be assigned using UTAX through USEARCH [

45], a high-throughput sequence analysis tool integrated into QIIME [

43,

44,

46], an open-source microbiome bioinformatics platform. For each sample, vectors of phylotype proportions will be clustered into community state types by computing Jensen-Shannon distances between all pairs of community states and applying hierarchical clustering using the Jensen-Shannon distance data and Ward linkage [

47].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The chao1, abundance-based coverage estimator (ACE), inverse Simpson, and Shannon indices were used to evaluate the alpha-diversity of the gut microbiome. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used for statistical evaluation of alpha diversity between S. Mansoni non-infected (NI) vs. infected individuals with CAA levels greater than 3pg/mL. Beta-diversity distance was visualized using Bray-Curtis Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA). Linear regression model outcome variable was Hep B effectiveness vs chao1 alpha diversity, adjusted for infection status at baseline. Infection status was a mediating factor between microbiome diversity vs the long-term effectiveness of the vaccine. Bivariate analyses were used to test the difference of alpha diversity by infection status and by location. Linear regression analyses were adjusted for age and sex and paired t-tests were used to evaluate for the significance of the association.

2.6. Ethical Approval

The study received ethical approval by the Uganda Virus Research Institute Research Ethics Committee, reference number GC/127/15/07/439, and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology, reference number HS 1850. Documented Informed written consent was obtained from all participants before taking part in any study procedures.

3. Results

We recruited a total of 113 study participants. Six participants were excluded due to unknown or unclear infection status. The final analysis included 107 participants recruited at baseline, with 63 (59%) from the Kampala site and 44 (41%) from the fishing community (see

Table 1). There was no significant difference in age by site or infection status (p=0.261). Over half of the participants [58%, 62/107] completed the three-dose Hepatitis B vaccine treatment, with all samples available, including plasma and stool samples for gut microbiome analysis. The mean age of the two communities was 28.1 years, with the majority being female (70%). Approximately 42 individuals (39%) had S. mansoni infection at baseline. There was a significant difference by sex (p<0.001) and infection status (p<0.001) at baseline between the two sites. These two variables will be adjusted as covariates in the following analysis

3.1. Microbiome Composition Analysis

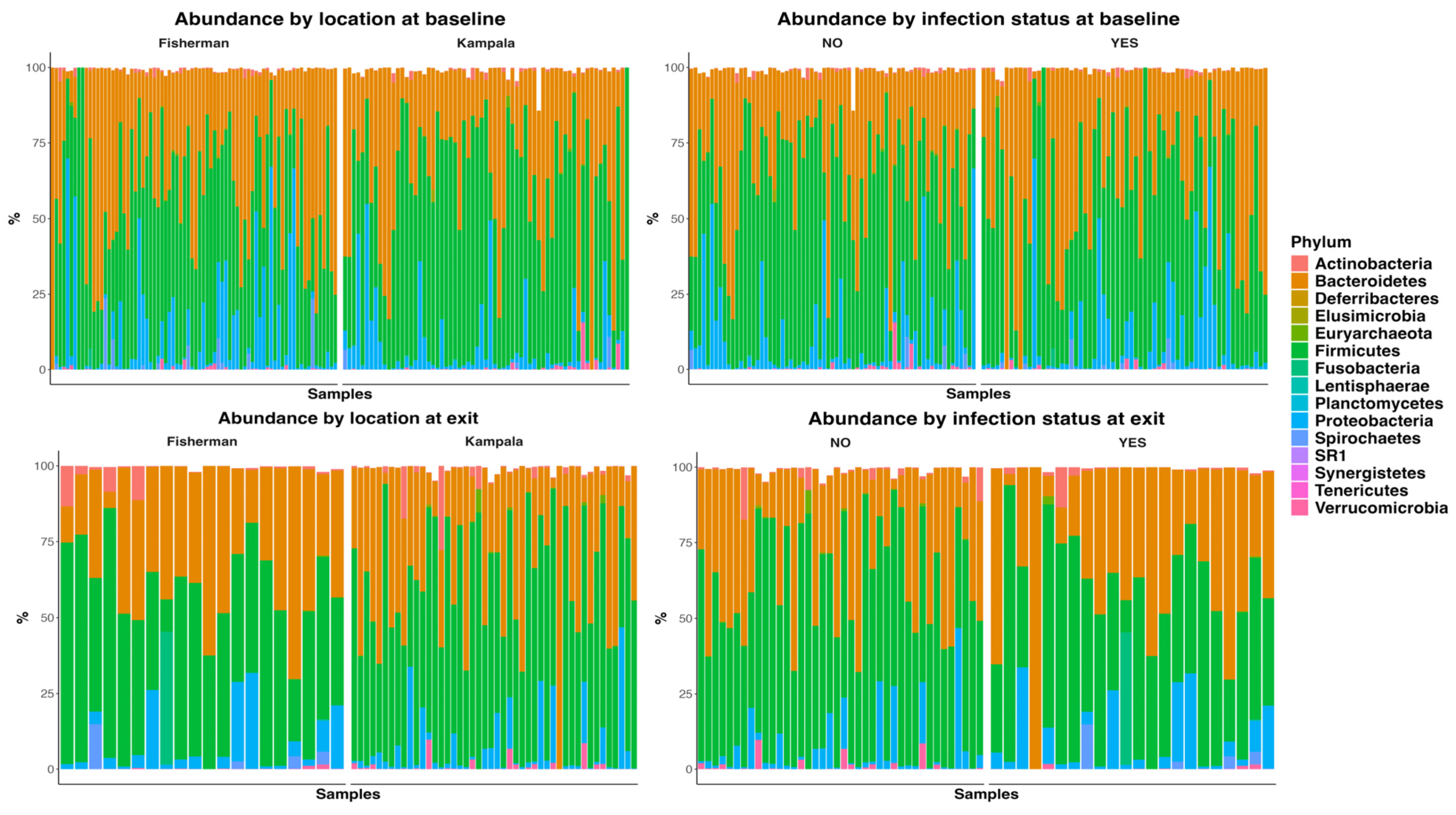

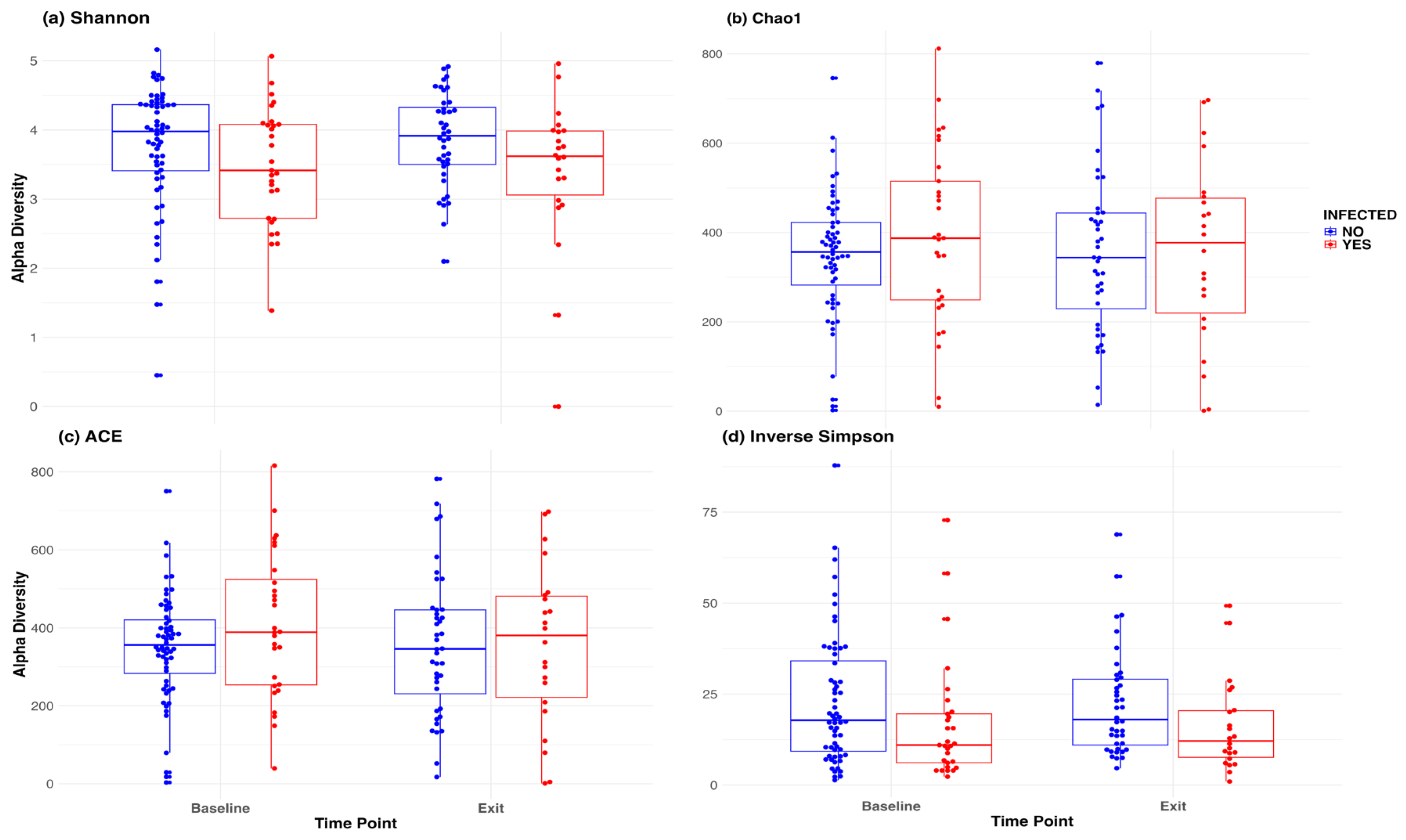

Figure 2 presented the abundance plots at the phylum level by location and infection status, at both baseline and D365. There was no significant difference in microbiome composition at the phylum level. The Welch two-sample t-test indicated no significant difference between infection statuses at baseline in Shannon (p = 0.24), Chao 1 (p = 0.30), ACE index (p = 0.16), and inverse Simpson (p = 0.12). Similarly, there was no significant difference at exit, with Shannon (p = 0.07), Chao 1 (p = 0.98), ACE index (p = 0.99), and inverse Simpson (p = 0.08).

We also used a paired t-test to determine whether there was a significant change in the microbiome between baseline and 12-month exit. No significant differences were observed by infection status using the above four alpha diversity measures.

Figure 3 included a box plot comparing alpha diversity measures by infection status over time. None of the comparisons indicated significance, as all p-values were greater than 0.05. The microbiome at baseline and exit are relative stable for the participants at both sites, and by infection status.

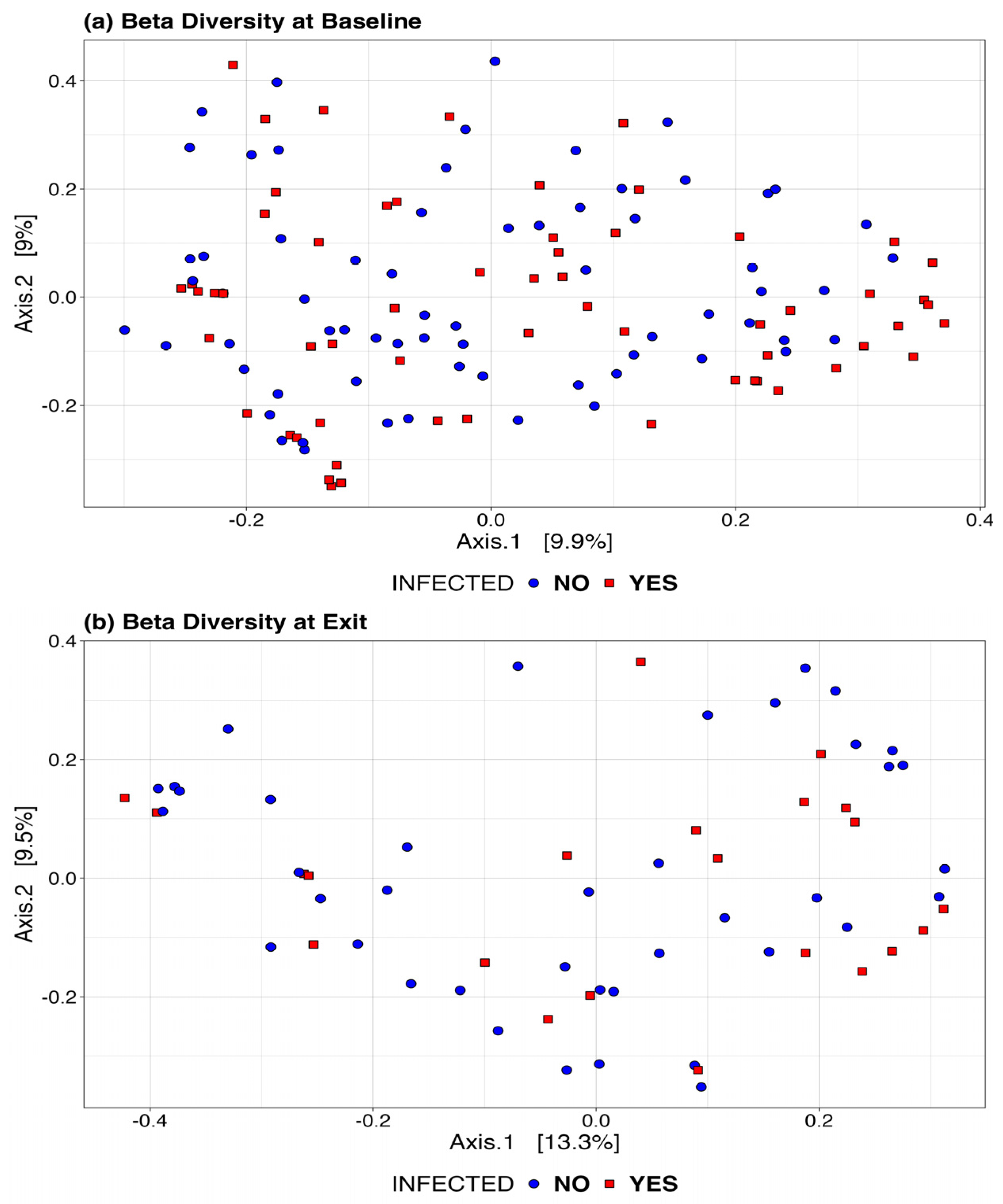

Figure 4 presents the Bray-Curtis measure for beta diversity by infection status at baseline and at exit. We did not observe significant differences or patterns by infection status in these figures. At both baseline and exit, there is no clear separation or diversity pattern by infection status, indicating that the microbial communities are not significantly different.

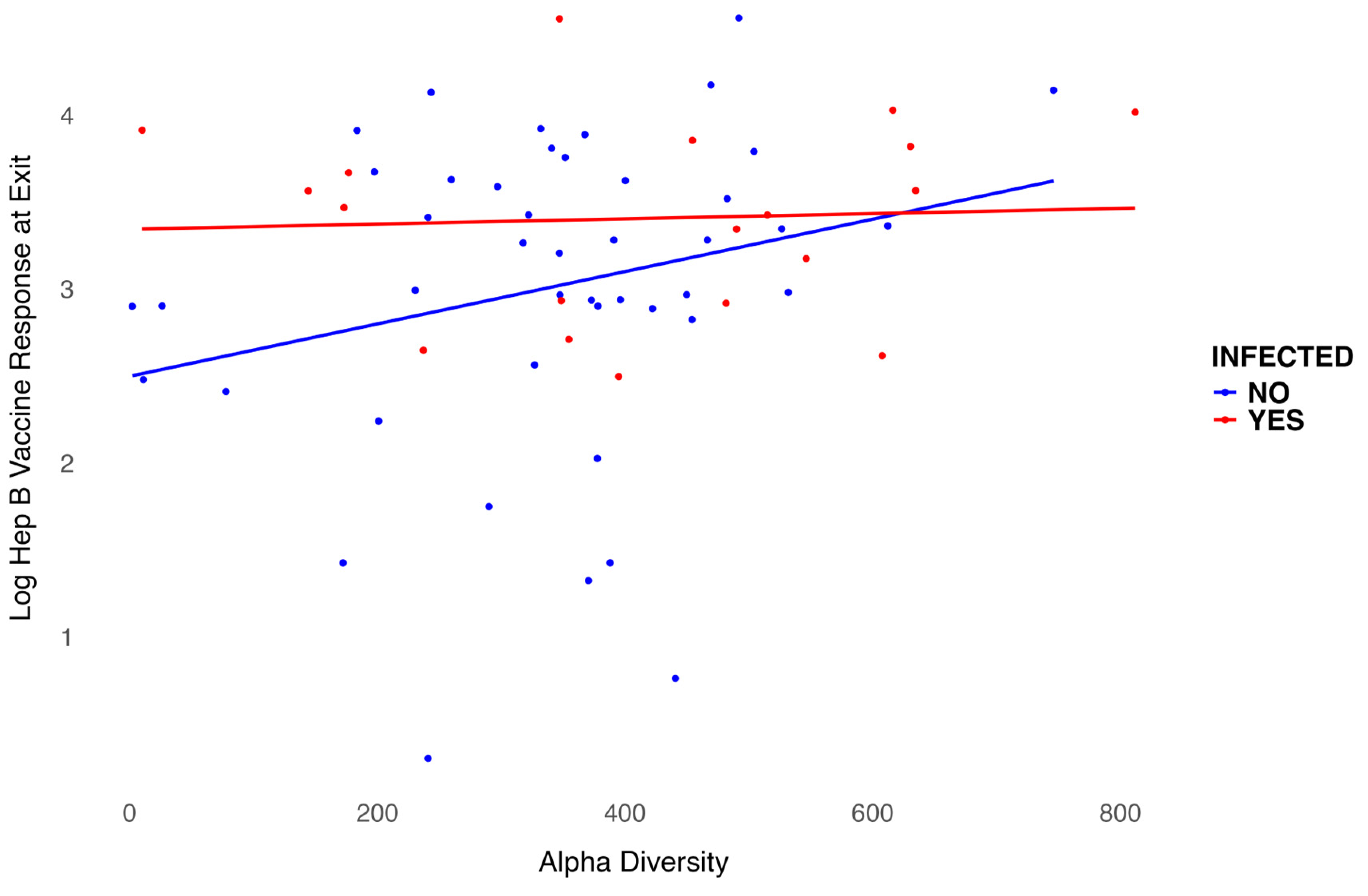

3.2. Regression Model

We modeled the log-transformed Hep B vaccine antibody level at exit, which is six months after the three-dose vaccination series, including baseline alpha diversity, infection status, and their interaction, while adjusting for age and sex. Age was negatively associated with the six-month antibody level after vaccination (p = 0.001), as shown in

Table 2. Females exhibited higher antibody levels compared to males, though this association was not significant. However, infection status was significantly associated with antibody levels (p = 0.02). For participants infected with S. mansoni, baseline alpha diversity measures were associated with lower six-month antibody levels after vaccination, even though treatment was provided before vaccination. In contrast, for participants who were not infected, baseline alpha diversity measures were associated with higher six-month antibody levels after vaccination. The interaction between infection status and alpha diversity was not significant (

Figure 5). Overall, baseline alpha diversity, infection status, their interaction, age, and sex accounted for 25% of the variation in antibody levels six months after the three-dose Hep B vaccination series. In addition, we included in the appendix that use other alpha diversity measures in the regression analysis and plots. Though the trend is still similar, Infection status is not significant in other models using Shannon index (Appendix S1), ACE (Appendix S2), or Inverse Simpson (Appendix S3).

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the role of the microbiome and S. mansoni infection status in the response and effectiveness of the Hep B vaccine. We are working with two infections simultaneously: S. mansoni infection (treated) and the immune response to the Hep B vaccine, measured by antibody levels. Although no significant differences in the microbiome were observed at any given time point, by site, or by location, the microbiome—particularly the Chao1 index—indicates that baseline microbiome diversity may play a different role in the long-term effectiveness of the Hep B vaccine based on infection status, even when PRQ treatment was provided before vaccination. The uniqueness of the Chao1 index is particularly useful for measuring the richness of diversity when some species are rare or underrepresented. It corrects for rare species that might not be captured in samples with lower sampling depth, where rare species are less well represented.

There is growing evidence linking the gut microbiota to immune function, but its role in vaccine immunity is still not fully understood. Research has shown that immune responses to oral vaccines for enteric infections show impaired efficacy in developing countries particularly in rural areas, such as the Lake Victoria fishing community studied here [

48]. For example, a case-control study in Ghana found that the composition of the intestinal microbiome was closely related to the immunogenicity of the rotavirus vaccine (RVV), potentially explaining the reduced efficacy observed in these regions [

49]. Our model suggests that infection status and age are important to the long-term effectiveness of the intravenous Hep B vaccine, as well as a marginal Independent significant (p=0.08) effect of baseline gut alpha diversity. Though our study did find an interaction between alpha diversity and long-term effectiveness of the vaccine by infection status, the results were not statistically significant. Our results are generally in line with existing research highlighting the complex, bidirectional relationship between the gut microbiota and vaccine efficacy. A randomized clinical trial on the MucoRice-CTB cholera vaccine found that those who responded to vaccination exhibited increased alpha-diversity in their microbiomes compared to non-responders, and that neutralizing antibodies against diarrheal toxins were generated in a microbiota-dependent manner [

50]. Conversely, a study of cholera vaccination in Bangladesh found no direct correlation between gut diversity and most immune responses, though individuals with higher levels of Clostridiales and lower levels of Enterobacterales were more likely to develop a memory B cell response [

51]. A longitudinal cohort study of COVID-19 vaccines found that that F. prausnitzii was associated with strong and sustained antibody responses following mRNA vaccination, while E. coli was linked to slower antibody decay after adenoviral vaccination [

52]. These findings suggest that the gut microbiota can influence vaccine-induced immune responses, and vaccination itself can alter the microbiome, but identifying the specific microbiome features that correlate with vaccine effectiveness remains a key challenge [

7]. While it is clear that the composition and diversity of the microbiome can influence vaccine outcomes, geographic differences in baseline microbiome diversity complicate these studies [

53,

54].

In this study, Schistosoma mansoni infection was treated with Praziquantel (PZQ). Sometimes, patients from villages or those with previous infections may need higher doses due to some degree of resistance to PZQ that can occur in S. mansoni. However, although the resistance level is low, intensive use in fishing communities due to the recurrence of the infection necessitates an alternative drug to treat S. mansoni, as already noted in the literature [

55,

56,

57]. This study highlights the importance of treating infections before vaccination, as infection status may have a lasting impact on the effectiveness of vaccination. We did not evaluate the biological mechanisms underlying how certain infection statuses might interact with the immune system through microorganisms that influence antibody-level development after vaccination. Further investigation is needed to explore the effects of infections, such as S. mansoni, on immune response and systemic health.

This study has several limitations. These included significant loss to follow-up, limited availability of true negative controls (i.e. unexposed individuals living in parasite-endemic fishing villages), and a lack of lifestyle data (i.e. diet, smoking, alcohol use). The fishing community has high mobility during the one-year follow-up of the study [

58,

59], with most people moving out due to economic challenges, especially among females [

60,

61,

62]. Despite the limited sample size, we were still able to demonstrate the necessity of infection control and the importance of maintaining a balanced gut microbiome, which can benefit long-term vaccine effectiveness. S. mansoni infection is very common in the fishing community, with infection and reinfection occurring frequently. It is almost impossible to find individuals who are not infected at the time of Hepatitis B vaccine initiation in this area. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the association of this infection and its impact on the microbiome and the long-term effectiveness of the vaccine. We collected lifestyle variables such as diet, alcohol use, and other factors that may impact the long-term effectiveness of the vaccine. However, we did not include them in this analysis due to inconsistencies and the further reduction in sample size and statistical power. We aim to emphasize a global-level analysis and an overall evaluation of the importance of future interventions targeting S. mansoni infection in this community.

The Kampala cohort (Good Health for Women cohort) set up between 2008 and 2009, was established to recruit women involved in high-risk sexual behavior, resulting in a gender imbalance by design [

63]. The aim was to better understand the dynamics of HIV/STI infection to inform future HIV prevention intervention trials in this group. Studies have documented high rates of HIV and STIs among women involved in high-risk behaviors and prevalence of STIs in the cohort including HIV is high (37%). Since HBV is transmitted both sexually and non-sexually, It is plausible that this cohort of high-risk women may not account for a good range of exposure risks that are present in fishing communities [

64,

65,

66]. In both fishing communities and high-risk cohort of women, sexual transmission is a potential dominant route of transmission for HBV [

67]. The findings should be interpreted considering variations in sex distribution and background characteristics. The gut microbiome data were only available at baseline and at the exit of the study; we did not collect gut microbiome data after treatment for infection or at each vaccine dosage. The Chao1 index indicated differences in rare and underrepresented species, but our sequencing depth was insufficient to evaluate species-level variations, as the 16S data are only reliable up to the genus level. Nevertheless, this study provides a foundation suggesting that certain rare species may influence vaccine effectiveness in the long term. Longer and more in-depth studies are needed to investigate the role of species-level variations on vaccine effectiveness, particularly under different infection statuses. Additionally, this study evaluated a population in Uganda, where Hep B infection and

S. mansoni infection are highly prevalent.

This study suggests that vaccine programs should consider addressing infection status and microbiome richness before implementing longer-dose vaccination schedules. In this study, we provided treatment for S. mansoni infection before initiating the Hep B vaccination, adhering to ethical regulations. This approach underscores the importance of conducting health and wellness checks prior to immunization. The complex interplay between microbiome and vaccine efficacy could be influenced by infection status. While the potential environmental, social and behavioral factors were not considered, these findings provide valuable insights for future studies to explore. For example, dietary interventions to optimize baseline microbiome status and treatment of infections, particularly in areas with high prevalence of infections and malnutrition, may improve the effectiveness of Hepatitis B vaccine antibody levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, YW, BO, and SM; methodology, YW, AW, BO, SM; software, YW, AW, GB, AS; formal analysis, YW, AW; investigation, YW, BO, and SM; resources, BO, GB, AS; data curation, YW, AW, GB, AS, JM, AN EK DK, JL, YM, BO, SM; writing-original draft preparation, YW, AW, BO, SM; writing—review and editing, YW, AW, GB, AS, BO, SM; visualization, YW, AW, GB, AS, BO, and SM; supervision, YW, BO, SM; project administration, GB, AS, JM, AN, EK, DK, JL, YM, BO. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received ethical approval by the Uganda Virus Research Institute Research Ethics Committee, reference number GC/127/15/07/439, and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology, reference number HS 1850. Documented Informed written consent was obtained from all participants before taking part in any study procedures.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this study are available upon reasonable request to corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and sincerely thank all study subjects for their participation and support in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Jordan A, Carding SR, Hall LJ. The early-life gut microbiome and vaccine efficacy. The Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e787–e794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasova AN, Takanashi S, Miyazaki A, Rajashekara G, Saif LJ. How the gut microbiome regulates host immune responses to viral vaccines. Current opinion in virology 2019, 37, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The influence of the intestinal microbiome on vaccine responses. Vaccine 2018, 36, 4433–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenyogbe N, Kollmann TR, Ben-Othman R. Early-life host–microbiome interphase: the key frontier for immune development. Frontiers in pediatrics 2017, 5, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogra SK, Chung CK, Wang D, Sakwinska O, Colombo Mottaz S, Sprenger N. Nurturing the early life gut microbiome and immune maturation for long term health. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell research 2020, 30, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciabattini A, Olivieri R, Lazzeri E, Medaglini D. Role of the microbiota in the modulation of vaccine immune responses. Frontiers in microbiology 2019, 10, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn DJ, Pulendran B. The potential of the microbiota to influence vaccine responses. Journal of leukocyte biology 2018, 103, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodin P, Davis MM. Human immune system variation. Nature reviews immunology 2017, 17, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponziani FR, Coppola G, Rio P, Caldarelli M, Borriello R, Gambassi G, et al. Factors influencing microbiota in modulating vaccine immune response: a long way to go. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen-Orr SS, Furman D. Variability in the immune system: of vaccine responses and immune states. Current opinion in immunology 2013, 25, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez Y, Brown EM, Finlay BB. Influence of the microbiota on vaccine effectiveness. Trends in immunology 2014, 35, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda MN, Lewis Z, Kalanetra KM, Rashid M, Ahmad SM, Raqib R, et al. Stool microbiota and vaccine responses of infants. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e362–e372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abavisani M, Ebadpour N, Khoshrou A, Sahebkar A. Boosting vaccine effectiveness: the groundbreaking role of probiotics. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2024, 101189. [CrossRef]

- Vlasova AN, Kandasamy S, Chattha KS, Rajashekara G, Saif LJ. Comparison of probiotic lactobacilli and bifidobacteria effects, immune responses and rotavirus vaccines and infection in different host species. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology 2016, 172, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardi PV, Tang ML. Vaccine adjuvant properties of probiotic bacteria. Discovery medicine 2011, 12, 525–533. [Google Scholar]

- Vitetta L, Saltzman ET, Thomsen M, Nikov T, Hall S. Adjuvant probiotics and the intestinal microbiome: enhancing vaccines and immunotherapy outcomes. Vaccines 2017, 5, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science 2011, 331, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh JZ, Ravindran R, Chassaing B, Carvalho FA, Maddur MS, Bower M, et al. TLR5-mediated sensing of gut microbiota is necessary for antibody responses to seasonal influenza vaccination. Immunity 2014, 41, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The influence of probiotics on vaccine responses–a systematic review. Vaccine 2018, 36, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zhou J, Yang Y, Chen X, Chen L, Wu Y. Intestinal Microbiota and Its Effect on Vaccine-Induced Immune Amplification and Tolerance. Vaccines 2024, 12, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arioz Tunc H, Childs CE, Swann JR, Calder PC. The effect of oral probiotics on response to vaccination in older adults: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Age and Ageing 2024, 53 (Suppl. 2), ii70–ii79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exum NG, Kibira SP, Ssenyonga R, Nobili J, Shannon AK, Ssempebwa JC, et al. The prevalence of schistosomiasis in Uganda: A nationally representative population estimate to inform control programs and water and sanitation interventions. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2019, 13, e0007617. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenberg, S. Uganda's struggle with schistosomiasis. The Lancet 2014, 383, 1707–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir R, Metcalf T, Fourati S, Bartsch Y, Kyosiimire-Lugemwa J, Canderan G, et al. Schistosoma mansoni infection alters the host pre-vaccination environment resulting in blunted Hepatitis B vaccination immune responses. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2023, 17, e0011089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanya RE, Muhangi L, Nampijja M, Nannozi V, Nakawungu PK, Abayo E, et al. Schistosoma mansoni and HIV infection in a Ugandan population with high HIV and helminth prevalence. Trop Med Int Health 2015, 20, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ssetaala A, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Asiki G, Kyakuwa N, Mpendo J, Van Dam GJ, et al. Schistosoma mansoni and HIV acquisition in fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda: a nested case-control study. Trop Med Int Health 2015, 20, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bullington BW, Klemperer K, Mages K, Chalem A, Mazigo HD, Changalucha J, et al. Effects of schistosomes on host anti-viral immune response and the acquisition, virulence, and prevention of viral infections: A systematic review. PLoS pathogens 2021, 17, e1009555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzscheiter M, Layland LE, Loffredo-Verde E, Mair K, Vogelmann R, Langer R, et al. Lack of host gut microbiota alters immune responses and intestinal granuloma formation during schistosomiasis. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 2014, 175, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark KA, Rinaldi G, Cortés A, Costain A, MacDonald AS, Cantacessi C. The role of the host gut microbiome in the pathophysiology of schistosomiasis. Parasite Immunology 2023, 45, e12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitandwe PK, Muyanja E, Nakaweesa T, Nanvubya A, Ssetaala A, Mpendo J, et al. Hepatitis B prevalence and incidence in the fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. BMC public health 2021, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard CW, Simard EP, Finelli L, Fiore AE, Bell BP. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiologic reviews 2006, 28, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opendi, S. World hepatitis day 2018: press statement on the progress of implementation of Hepatitis B vaccination program in Uganda. Govt Uganda. 2018.

- Ocan M, Acheng F, Otike C, Beinomugisha J, Katete D, Obua C. Antibody levels and protection after Hepatitis B vaccine in adult vaccinated healthcare workers in northern Uganda. Plos one 2022, 17, e0262126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walayat S, Ahmed Z, Martin D, Puli S, Cashman M, Dhillon S. Recent advances in vaccination of non-responders to standard dose hepatitis B virus vaccine. World journal of hepatology 2015, 7, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo E-J, Cheong HS, Kwon M-J, Sohn W, Kim H-N, Cho YK. Relationship between gut microbiome diversity and hepatitis B viral load in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gut Pathogens 2021, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen Y, Wu S-D, Chen Y, Li X-Y, Zhu Q, Nakayama K, et al. Alterations in gut microbiome and metabolomics in chronic hepatitis B infection-associated liver disease and their impact on peripheral immune response. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2155018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbonye M, Seeley J, Nalugya R, Kiwanuka T, Bagiire D, Mugyenyi M, et al. Test and treat: the early experiences in a clinic serving women at high risk of HIV infection in Kampala. AIDS care 2016, 28 (suppl. 3), 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadrosh DW, Ma B, Gajer P, Sengamalay N, Ott S, Brotman RM, et al. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2014, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiwango RM, Bagaya B, Mpendo J, Joag V, Okech B, Nanvubya A, et al. Protocol for a randomized clinical trial exploring the effect of antimicrobial agents on the penile microbiota, immunology and HIV susceptibility of Ugandan men. Trials 2019, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor LM, editor The national institutes of health human microbiome project. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine; 2016: Elsevier.

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. The human microbiome project. Nature 2007, 449, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Applied and environmental microbiology 2006, 72, 5069–5072. [CrossRef]

- Can, M. Annotation of bacteria by Greengenes classifier using 16S rRNA gene hyper variable regions. Southeast Europe Journal of Soft Computing 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Liu YX, Li X. USEARCH 12: Open-source software for sequencing analysis in bioinformatics and microbiome. Imeta 2024, 3, e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana SDR. Optmizing 16S sequencing analysis pipelines 2016.

- Liu CM, Aziz M, Kachur S, Hsueh P-R, Huang Y-T, Keim P, et al. BactQuant: an enhanced broad-coverage bacterial quantitative real-time PCR assay. BMC microbiology 2012, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lopman BA, Pitzer VE, Sarkar R, Gladstone B, Patel M, Glasser J, et al. Understanding reduced rotavirus vaccine efficacy in low socio-economic settings. 2012.

- Harris VC, Armah G, Fuentes S, Korpela KE, Parashar U, Victor JC, et al. Significant correlation between the infant gut microbiome and rotavirus vaccine response in rural Ghana. The Journal of infectious diseases 2017, 215, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuki Y, Nojima M, Hosono O, Tanaka H, Kimura Y, Satoh T, et al. Oral MucoRice-CTB vaccine for safety and microbiota-dependent immunogenicity in humans: a phase 1 randomised trial. The Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e429–e440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chac D, Bhuiyan TR, Saha A, Alam MM, Salma U, Jahan N, et al. Gut microbiota and development of Vibrio cholerae-specific long-term memory B cells in adults after whole-cell killed oral cholera vaccine. Infection and immunity 2021, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong H, Yoon JG, Nham E, Choi YJ, Noh JY, Cheong HJ, et al. The gut microbiota modifies antibody durability and booster responses after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Journal of Translational Medicine 2024, 22, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G, Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome medicine 2016, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 2012, 486, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doenhoff MJ, Kusel JR, Coles GC, Cioli D. Resistance of Schistosoma mansoni to praziquantel: is there a problem? Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2002, 96, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picquet M, Vercruysse J, Shaw DJ, Diop M, Ly A. Efficacy of praziquantel against Schistosoma mansoni in northern Senegal. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1998, 92, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallon PG, Doenhoff MJ. Drug-resistant schistosomiasis: resistance to praziquantel and oxamniquine induced in Schistosoma mansoni in mice is drug specific. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 1994, 51, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, F. Mobility and fisherfolk livelihoods on Lake Victoria: implications for vulnerability and risk. Geoforum 2010, 41, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssetaala A, Ssempiira J, Nanyonjo G, Okech B, Chinyenze K, Bagaya B, et al. Mobility for maternal health among women in hard-to-reach fishing communities on Lake Victoria, Uganda; a community-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Services Research 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwena Z, Nakamanya S, Nanyonjo G, Okello E, Fast P, Ssetaala A, et al. Understanding mobility and sexual risk behaviour among women in fishing communities of Lake Victoria in East Africa: a qualitative study. BMC public health 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumwine C, Aggleton P, Bell S. Accessing HIV treatment and care services in fishing communities around Lake Victoria in Uganda: mobility and transport challenges. African Journal of AIDS Research 2019, 18, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamanya S, Okello ES, Kwena ZA, Nanyonjo G, Bahemuka UM, Kibengo FM, et al. Social networks, mobility, and HIV risk among women in the fishing communities of Lake Victoria. BMC Women's Health 2022, 22, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013, 40, 187–193. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiki G, Mpendo J, Abaasa A, Agaba C, Nanvubya A, Nielsen L, et al. HIV and syphilis prevalence and associated risk factors among fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sexually transmitted infections 2011, 87, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandera SO, Tumwesigye NM, Walakira EJ, Kisaakye P, Wagman J. Alcohol use, intimate partner violence, and HIV sexual risk behavior among young people in fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. BMC public health 2021, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssetaala A, Welsh S, Nakaweesa T, Wambuzi M, Nanyonjo G, Nanvubya A, et al. Healthcare use and sexually transmitted infections treatment-seeking: a mixed methods cross-sectional survey among hard-to-reach fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. The Pan African Medical Journal 2024, 48, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayanja Y, Rida W, Kimani J, Ssetala A, Mpendo J, Nanvubya A, et al. Hepatitis B status and associated factors among participants screened for simulated HIV vaccine efficacy trials in Kenya and Uganda. Plos one 2023, 18, e0288604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).