Submitted:

14 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Experiment Design

2.2. Fasting Blood Glucose Measurement

2.3. Fasting Serum Insulin Measurement

2.4. Mouse HOMA-IR Measurement

2.5. Glucose Tolerance Test

2.6. Immunohistochemistry for Protein Expression

2.7. Cell Experiment Design

2.8. 2-NBDG Glucose Uptake Assay

2.9. Cellular Immunofluorescence Staining for GLUT4

2.10. Western Blotting for AKT-GLUT4 Signaling Molecules

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

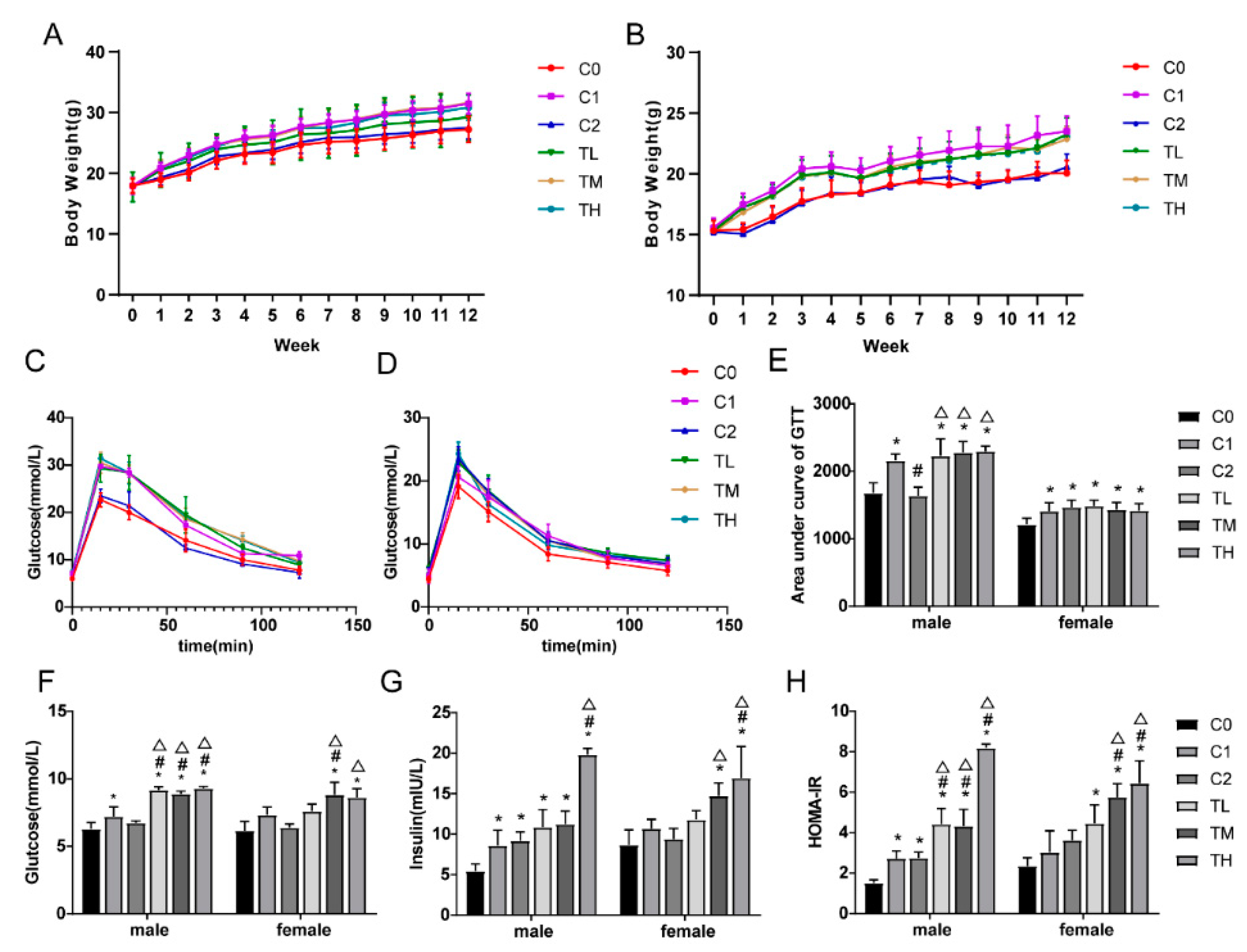

3.1. BPA in Combination with a High-Fat Diet Exacerbates Insulin Resistance

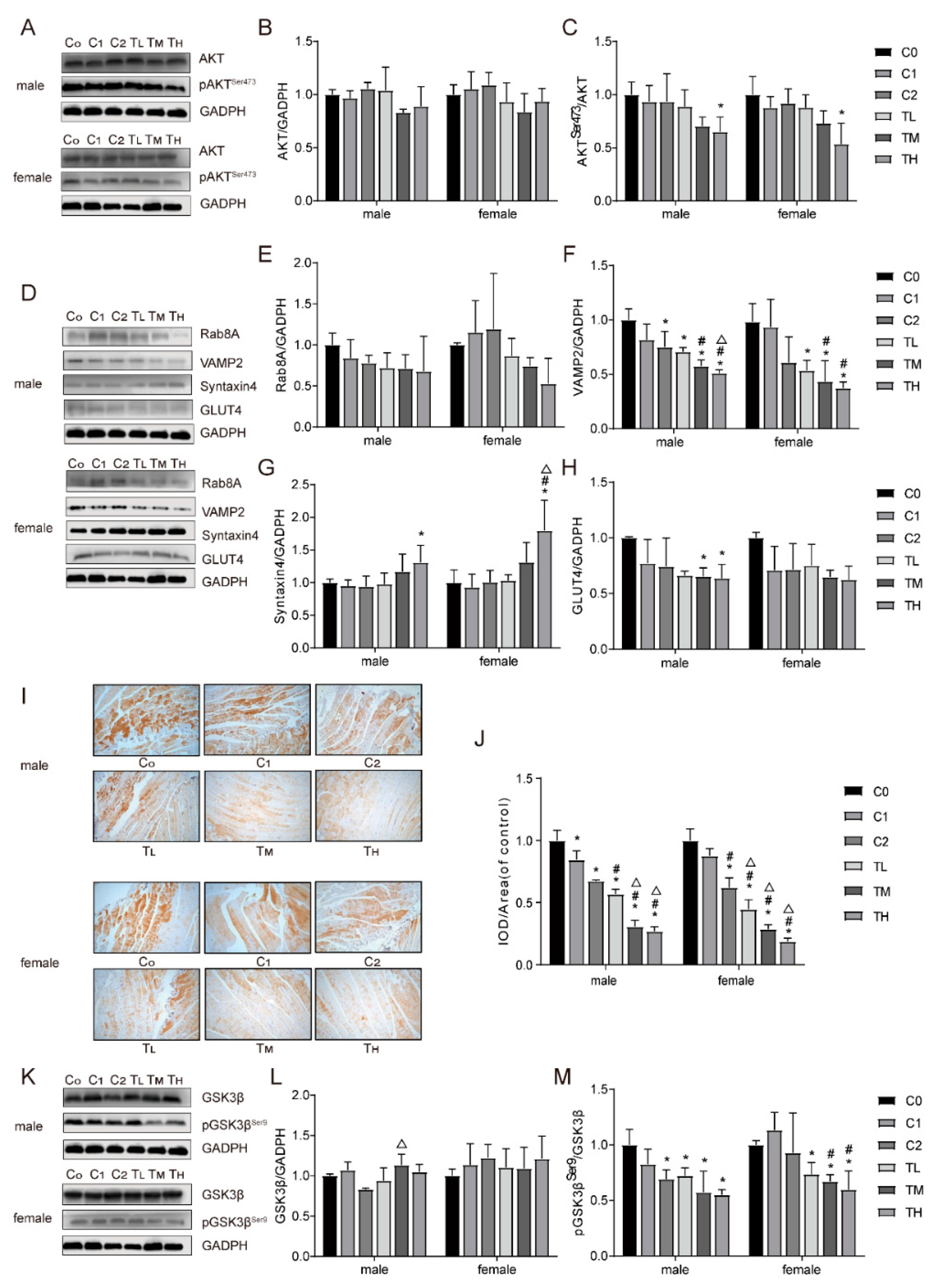

3.2. Co-Exposure to BPA and a High-Fat Diet Affects the Expression Levels of Insulin Signaling Molecules in Gastrocnemius Tissue

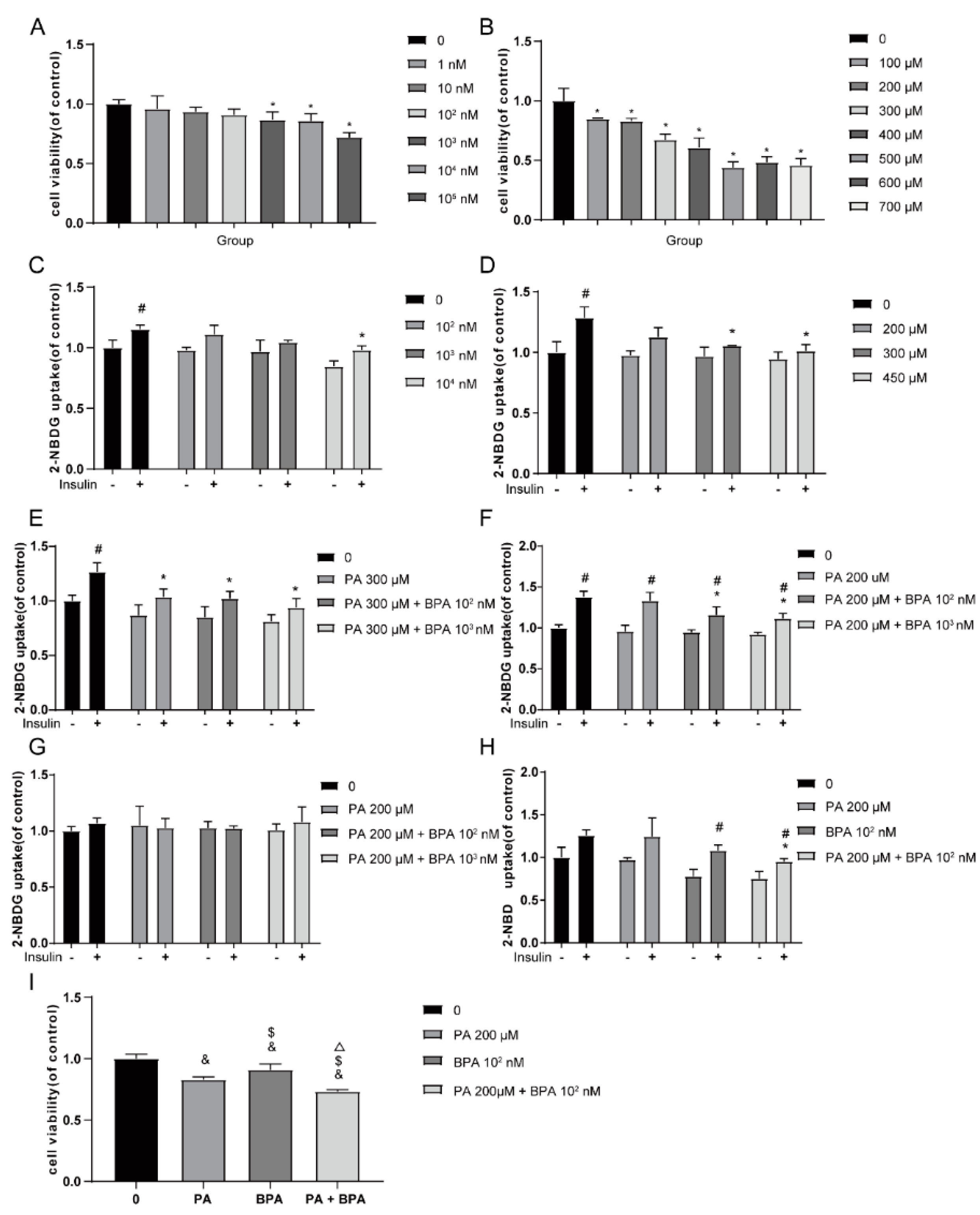

3.3. BPA in Combination with Palmitic Acid Significantly Reduces Glucose Uptake Levels in C2C12 Cells

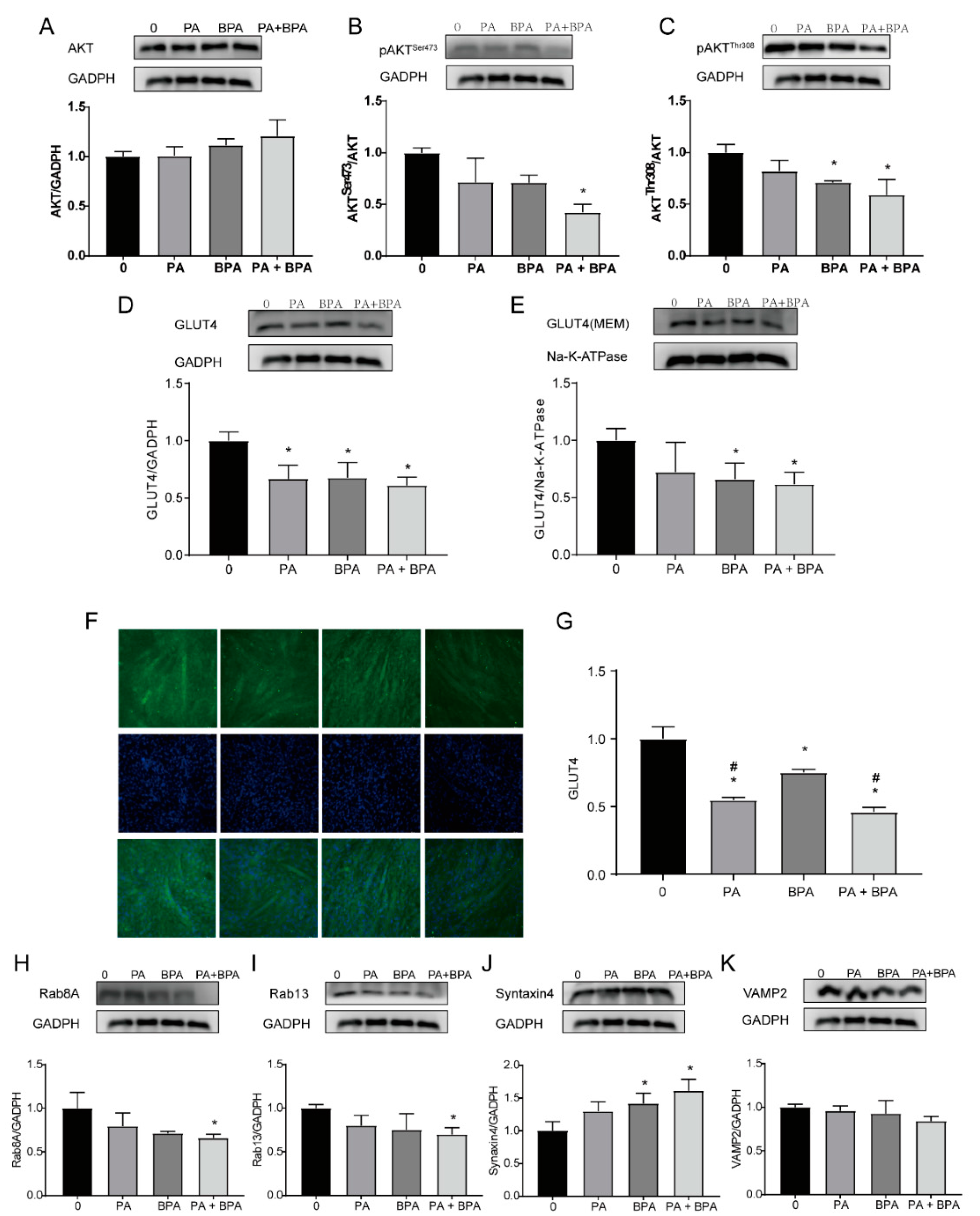

3.4. Co-Exposure to BPA and Palmitic Acid Inhibits Insulin Signaling and GLUT4 Translocation in C2C12 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Karuranga, S.; Malanda, B.; Williams, D. Call for data contribution to the IDF Diabetes Atlas 9th Edition 2019. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2018, 140, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mansour, M.A. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DMT2) in a Semi-Urban Saudi Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, S.C.; Seeley, R.J.; Rushing, P.A.; D'Alessio, D.; Tso, P. A Controlled High-Fat Diet Induces an Obese Syndrome in Rats. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KAHN S E, HULL R L, UTZSCHNEIDER K M. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 2006, 444, 840–6. [CrossRef]

- Small, L.; Brandon, A.E.; Turner, N.; Cooney, G.J. Modeling insulin resistance in rodents by alterations in diet: what have high-fat and high-calorie diets revealed? Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2018, 314, E251–E265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinault, C.; Caroli-Bosc, P.; Bost, F.; Chevalier, N. Critical Overview on Endocrine Disruptors in Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.C.; Shih, Y.-H.; Bryan, M.S.; Jackson, B.P.; Aguilar, D.; Hanis, C.L.; Argos, M.; Sargis, R.M. Relationships Between Urinary Metals and Diabetes Traits Among Mexican Americans in Starr County, Texas, USA. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2022, 201, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Hauser, R.; Marcus, M.; Olea, N.; Welshons, W.V. Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA). Reprod. Toxicol. 2007, 24, 139–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geens, T.; Goeyens, L.; Covaci, A. Are potential sources for human exposure to bisphenol-A overlooked? Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Heal. 2011, 214, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Chahoud, I.; Heindel, J.J.; Padmanabhan, V.; Paumgartten, F.J.; Schoenfelder, G. Urinary, Circulating, and Tissue Biomonitoring Studies Indicate Widespread Exposure to Bisphenol A. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2012, 17, 407–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RUSSO G, BARBATO F, MITA D G, et al. Occurrence of Bisphenol A and its analogues in some foodstuff marketed in Europe. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2019, 131, 110575. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafezi, S.A.; Abdel-Rahman, W.M. The Endocrine Disruptor Bisphenol A (BPA) Exerts a Wide Range of Effects in Carcinogenesis and Response to Therapy. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 12, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K. Usefulness of the metabolic syndrome criteria as predictors of insulin resistance among obese Korean women. Public Health Nutr 2009, 13, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FREEMAN A M, ACEVEDO L A, PENNINGS N. Insulin Resistance [M]. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Luis Acevedo declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Nicholas Pennings declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.; StatPearls Publishing.

- Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC. 2024.

- Ferrannini, E.; Simonson, D.C.; Katz, L.D.; Reichard, G.; Bevilacqua, S.; Barrett, E.J.; Olsson, M.; DeFronzo, R.A. The disposal of an oral glucose load in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Metabolism 1988, 37, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Tripathy, D. Skeletal Muscle Insulin Resistance Is the Primary Defect in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32 (Suppl. 2), S157–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Pereira, R.O.; O'Neill, B.T.; Riehle, C.; Ilkun, O.; Wende, A.R.; Rawlings, T.A.; Zhang, Y.C.; Zhang, Q.; Klip, A.; et al. Cardiac PI3K-Akt Impairs Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Uptake Independent of mTORC1 and GLUT4 Translocation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 27, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHARMA B R, KIM H J, RHYU D Y. Caulerpa lentillifera extract ameliorates insulin resistance and regulates glucose metabolism in C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in myocytes. Journal of translational medicine 2015, 13, 62. [CrossRef]

- LI W, LIANG X, ZENG Z, et al. Simvastatin inhibits glucose uptake activity and GLUT4 translocation through suppression of the IR/IRS-1/Akt signaling in C2C12 myotubes. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2016, 83, 194–200.

- Sun, Y.; Bilan, P.J.; Liu, Z.; Klip, A. Rab8A and Rab13 are activated by insulin and regulate GLUT4 translocation in muscle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19909–19914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullainadhan, V.; Viswanathan, M.P.; Karundevi, B. Effect of Bisphenol-A (BPA) on insulin signal transduction and GLUT4 translocation in gastrocnemius muscle of adult male albino rat. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 90, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FOSTER L J, KLIP A. Mechanism and regulation of GLUT-4 vesicle fusion in muscle and fat cells. American journal of physiology Cell physiology 2000, 279, C877–90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, J.G.; Forte, J.G. What is the role of SNARE proteins in membrane fusion? Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003, 285, C237–C249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessin, J.E.; Thurmond, D.C.; Elmendorf, J.S.; Coker, K.J.; Okada, S. Molecular Basis of Insulin-stimulated GLUT4 Vesicle Trafficking. Location! Location! Location! J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 2593–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, L.H.; Gould, G.W. The Vesicle- and Target-SNARE Proteins That Mediate Glut4 Vesicle Fusion Are Localized in Detergent-insoluble Lipid Rafts Present on Distinct Intracellular Membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 49750–49754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, W.T.; Maianu, L.; Zhu, J.H.; Brechtel-Hook, G.; Wallace, P.; Baron, A.D. Evidence for defects in the trafficking and translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters in skeletal muscle as a cause of human insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 2377–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HU F, B. Globalization of diabetes: the role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes care, 2011, 34, 1249–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahapary, D.L.; Pratisthita, L.B.; Fitri, N.A.; Marcella, C.; Wafa, S.; Kurniawan, F.; Rizka, A.; Tarigan, T.J.E.; Harbuwono, D.S.; Purnamasari, D.; et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of insulin resistance: Focusing on the role of HOMA-IR and Tryglyceride/glucose index. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2022, 16, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S.; Yada, T.; Ishikawa, N.; Taheruzzaman, K.; Hara, R.; Matsuzaki, T.; Nishikawa, A. Insulin-like growth factor 1 regulation of proliferation and differentiation of Xenopus laevis myogenic cells in vitro. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. - Anim. 2016, 53, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Kannan, K.; Tan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.; Widelka, M. Bisphenol Analogues Other Than BPA: Environmental Occurrence, Human Exposure, and Toxicity—A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5438–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmugi, A.; Ducheix, S.; Lasserre, F.; Polizzi, A.; Paris, A.; Priymenko, N.; Bertrand-Michel, J.; Pineau, T.; Guillou, H.; Martin, P.G.P.; et al. Low doses of bisphenol a induce gene expression related to lipid synthesis and trigger triglyceride accumulation in adult mouse liver. Hepatology 2012, 55, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z. 2-NBDG as a fluorescent indicator for direct glucose uptake measurement. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2005, 64, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Ai, L.; Wang, B.-F.; Zhou, Y. High glucose inhibits myogenesis and induces insulin resistance by down-regulating AKT signaling. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2019, 120, 109498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, N.; Yang, H.; Ye, X.; He, D.; Jin, X.; Liu, J.; Tian, C.; Li, H.; et al. High-fat diet aggravates glucose homeostasis disorder caused by chronic exposure to bisphenol A. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 221, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, S.; Pessin, J.E. An adipocentric view of signaling and intracellular trafficking. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2002, 18, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryer, L.G.D.; Foufelle, F.; Barnes, K.; Baldwin, S.A.; Woods, A.; Carling, D. Characterization of the role of the AMP-activated protein kinase in the stimulation of glucose transport in skeletal muscle cells. Biochem. J. 2002, 363, 167–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HAYASHI T, HIRSHMAN M F, KURTH E J, et al. Evidence for 5' AMP-activated protein kinase mediation of the effect of muscle contraction on glucose transport. Diabetes, 1998, 47, 1369–73.

- Kidani, T.; Kamei, S.; Miyawaki, J.; Aizawa, J.; Sakayama, K.; Masuno, H. Bisphenol A Downregulates Akt Signaling and Inhibits Adiponectin Production and Secretion in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2010, 17, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropero, A.B.; Soria, B.; Nadal, A. A Nonclassical Estrogen Membrane Receptor Triggers Rapid Differential Actions in the Endocrine Pancreas. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002, 16, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, N.J.; Gould, G.W. SNARE Proteins Underpin Insulin-Regulated GLUT4 Traffic. Traffic 2011, 12, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaldin-Fincati, J.R.; Pavarotti, M.; Frendo-Cumbo, S.; Bilan, P.J.; Klip, A. Update on GLUT4 Vesicle Traffic: A Cornerstone of Insulin Action. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Tamori, Y.; Kanda, H.; Yoshikawa, M.; Tateya, S.; Nishino, N.; Kasuga, M. The t-SNAREs syntaxin4 and SNAP23 but not v-SNARE VAMP2 are indispensable to tether GLUT4 vesicles at the plasma membrane in adipocyte. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 1336–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KAHN B B, FLIER J S. Regulation of glucose-transporter gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes care, 1990, 13, 548–64.

- Foster, L.J.; Yaworsky, K.; Trimble, W.S.; Klip, A. SNAP23 promotes insulin-dependent glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes: possible interaction with cytoskeleton. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 1999, 276, C1108–C1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.; Goedert, M. GSK3 inhibitors: development and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GULLI G, FERRANNINI E, STERN M, et al. The metabolic profile of NIDDM is fully established in glucose-tolerant offspring of two Mexican-American NIDDM parents. Diabetes, 1992, 41, 1575–86.

- COHEN, P. The Croonian Lecture 1998. Identification of a protein kinase cascade of major importance in insulin signal transduction. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological sciences, 1999, 354, 485–95. [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS K V, PRICE J C, KELLEY D E. Interactions of impaired glucose transport and phosphorylation in skeletal muscle insulin resistance: a dose-response assessment using positron emission tomography. Diabetes, 2001, 50, 2069–79.

- Carnagarin, R.; Dharmarajan, A.M.; Dass, C.R. Molecular aspects of glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle – A focus on the molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 417, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanvee, G.M.; Panajatovic, M.V.; Bouitbir, J.; Krähenbühl, S. Mechanisms of insulin resistance by simvastatin in C2C12 myotubes and in mouse skeletal muscle. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 164, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).