Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

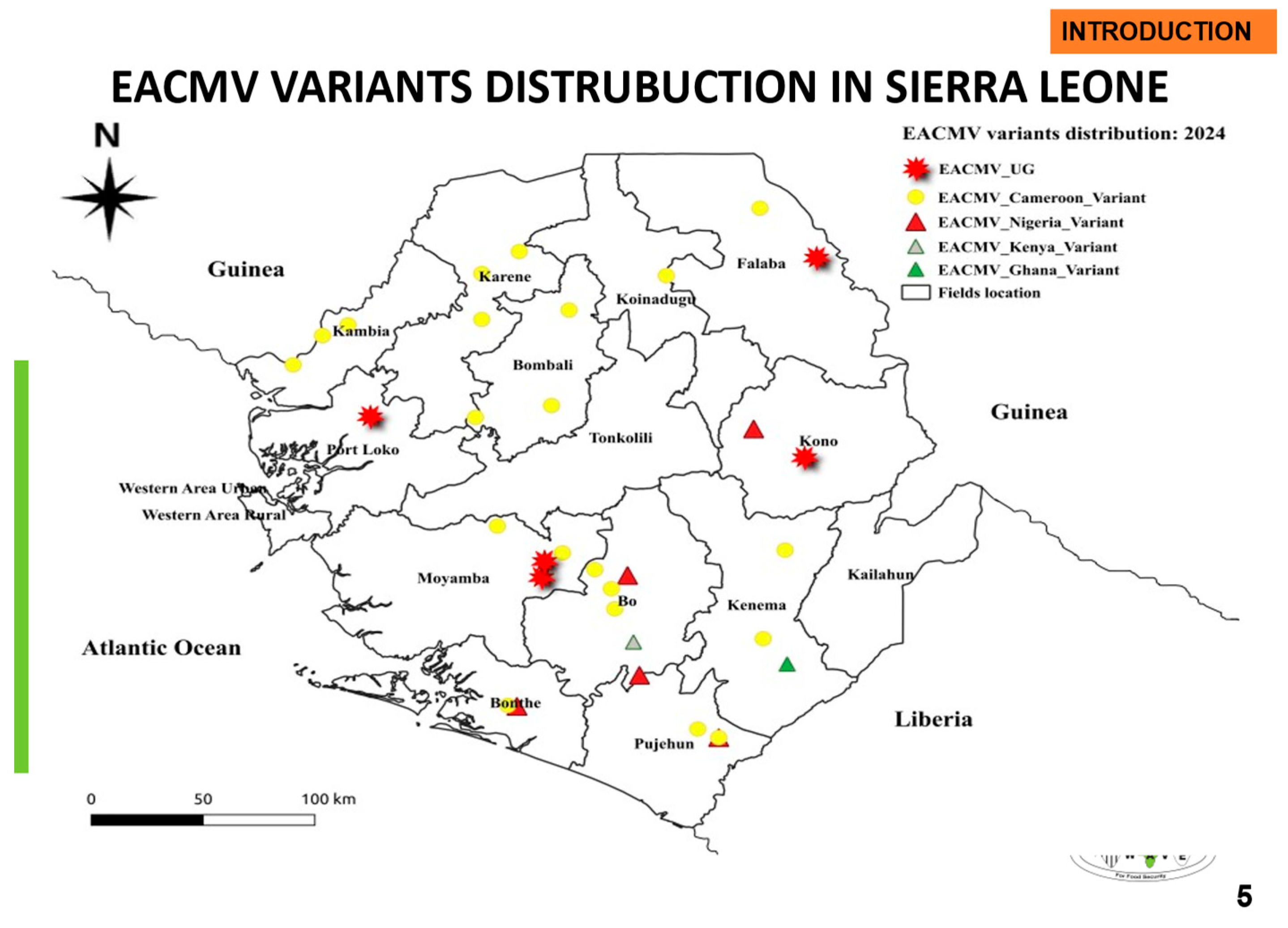

1. Introduction

2. Results

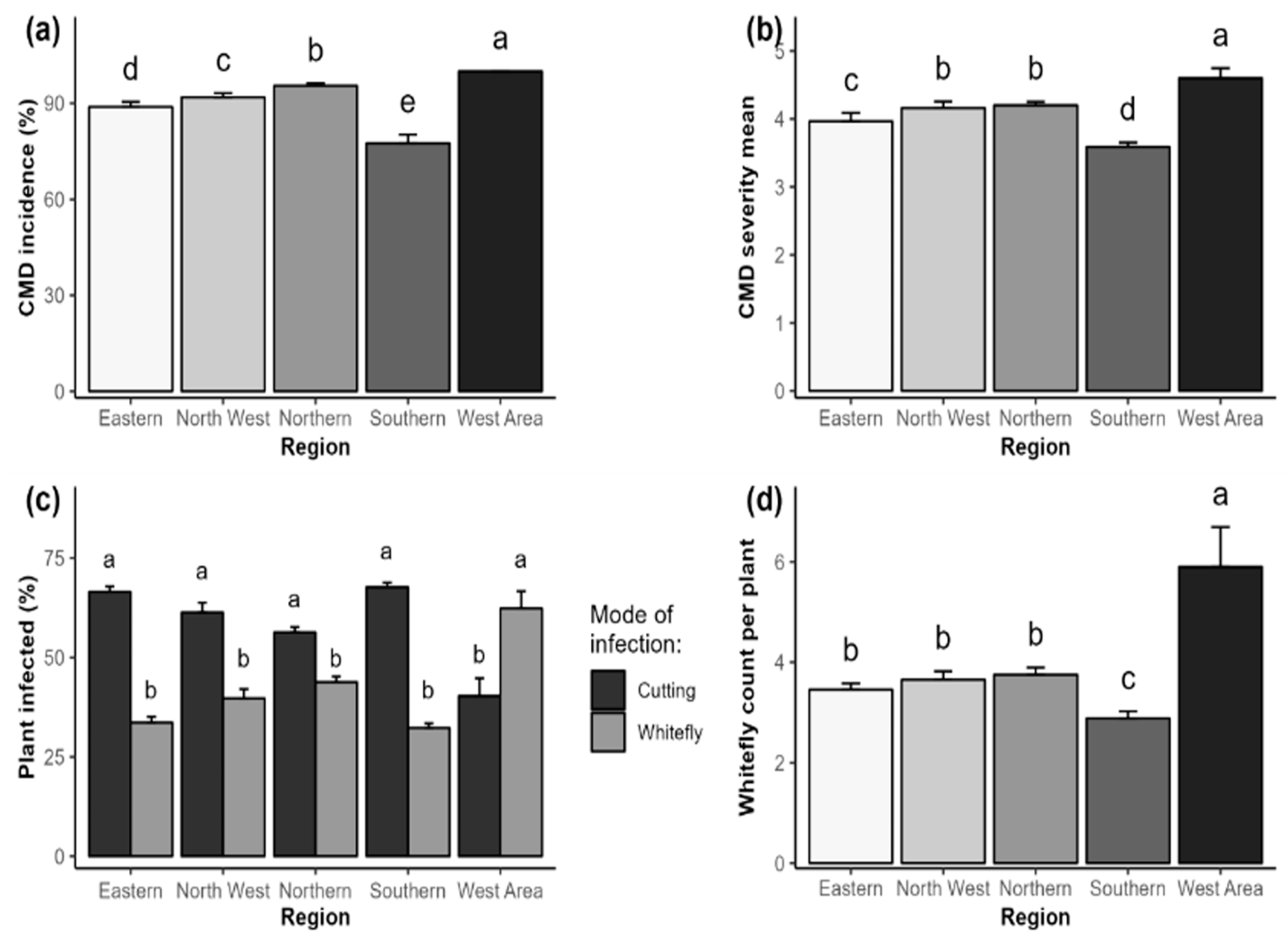

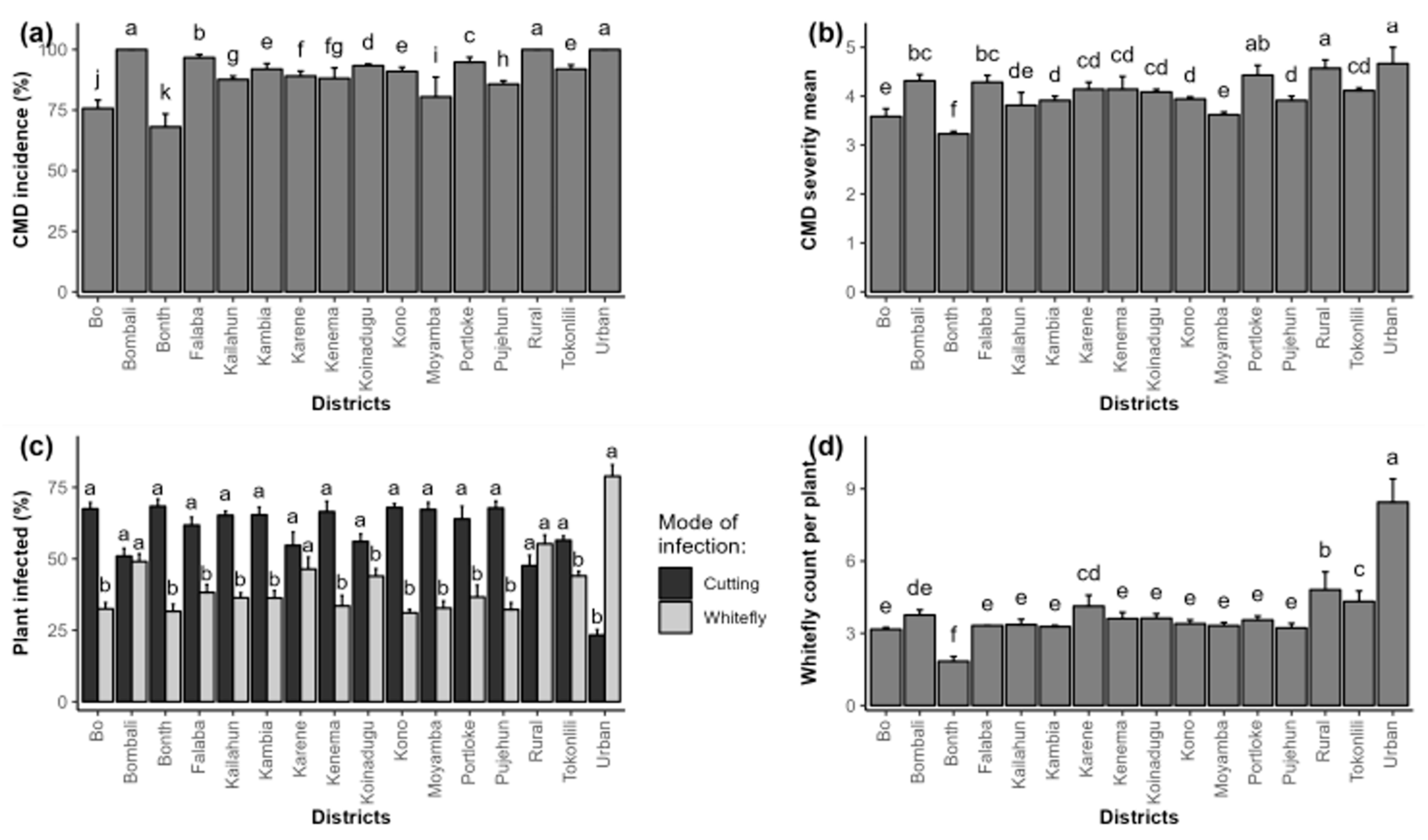

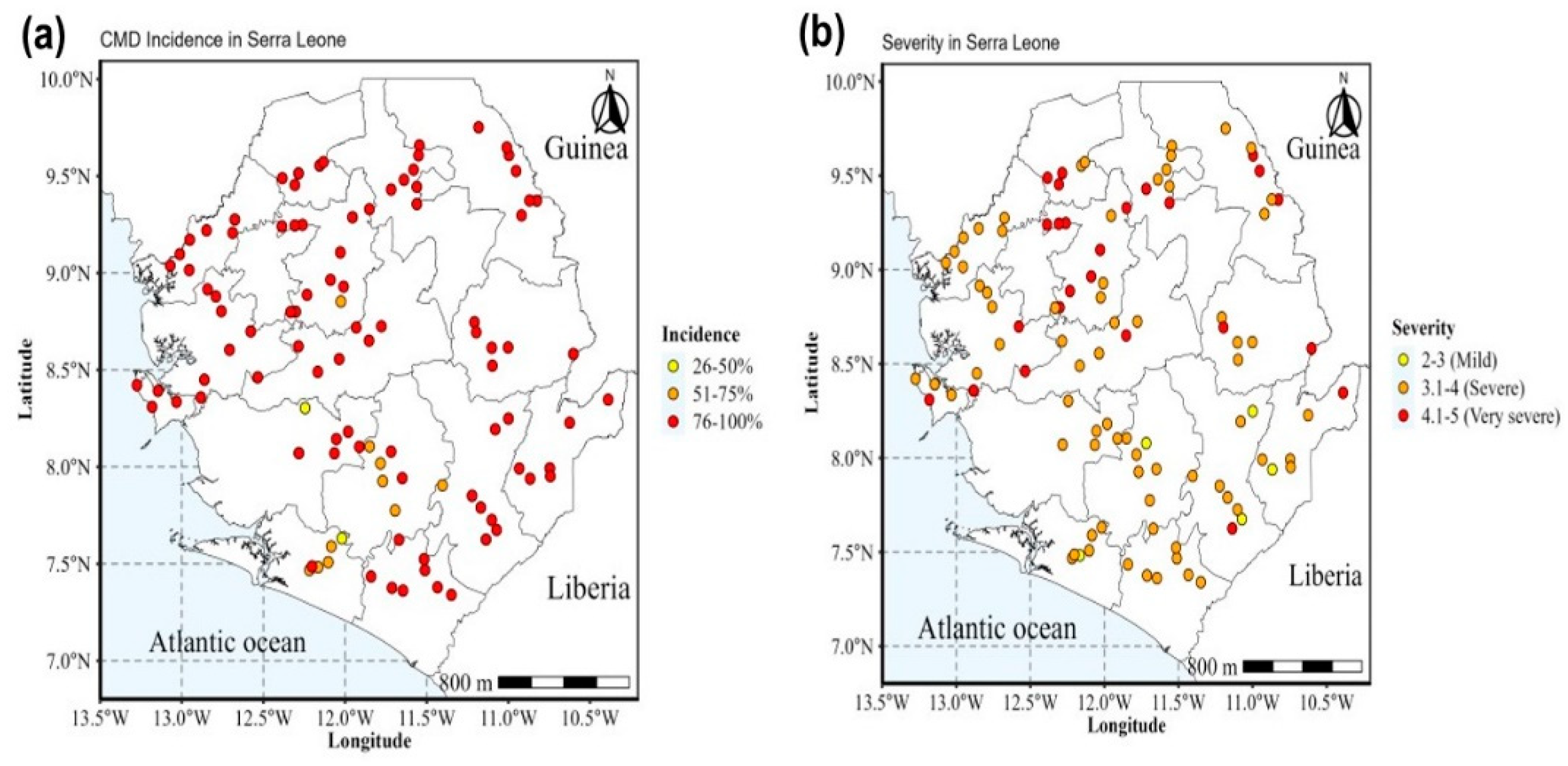

2.1. Phenotypic Detection and Distribution of Cassava Mosaic Disease

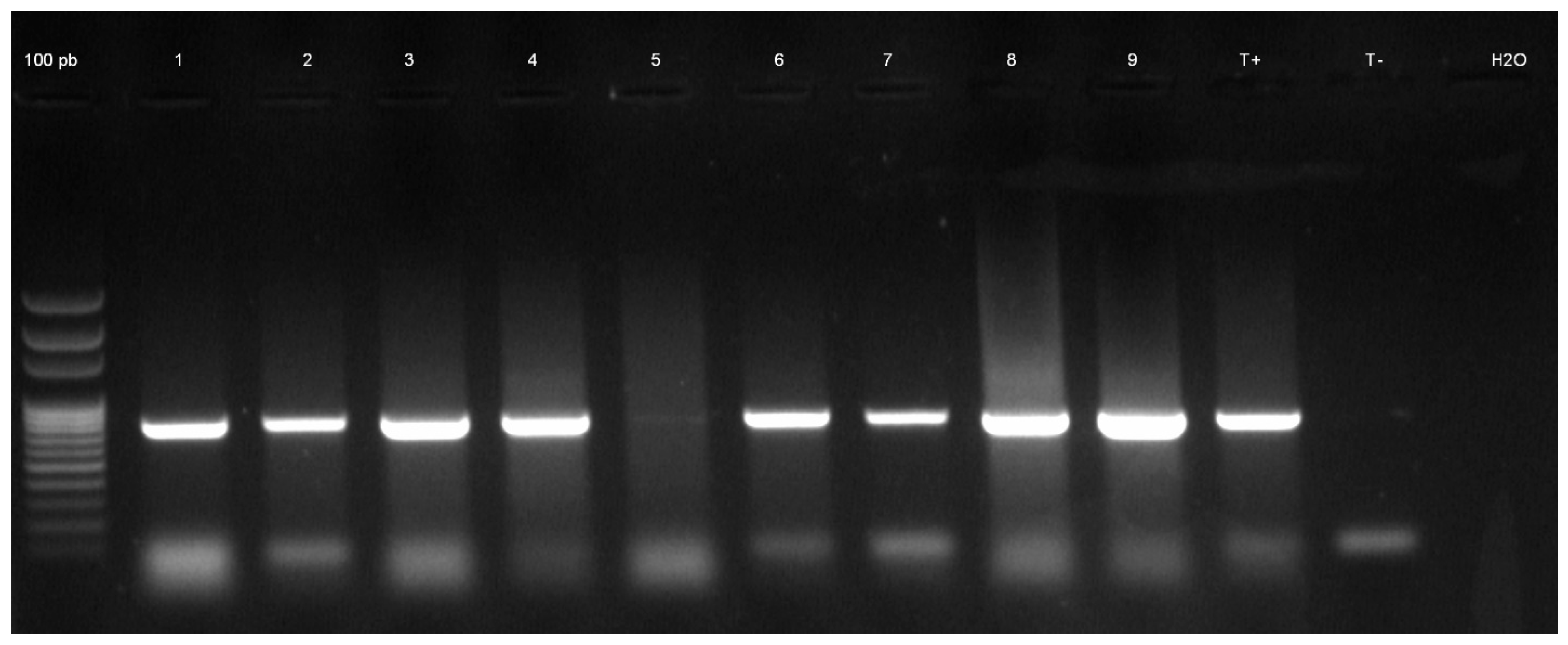

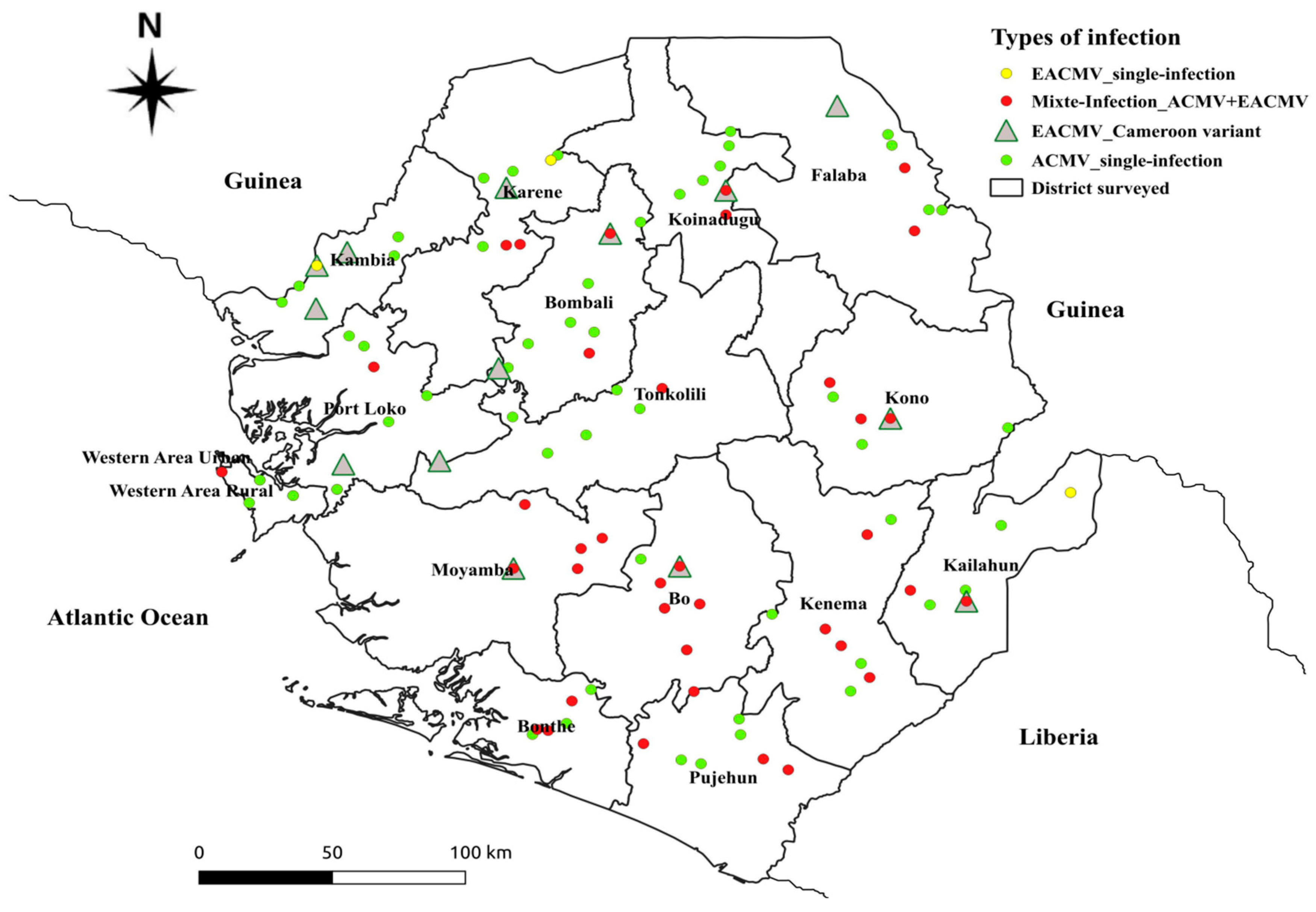

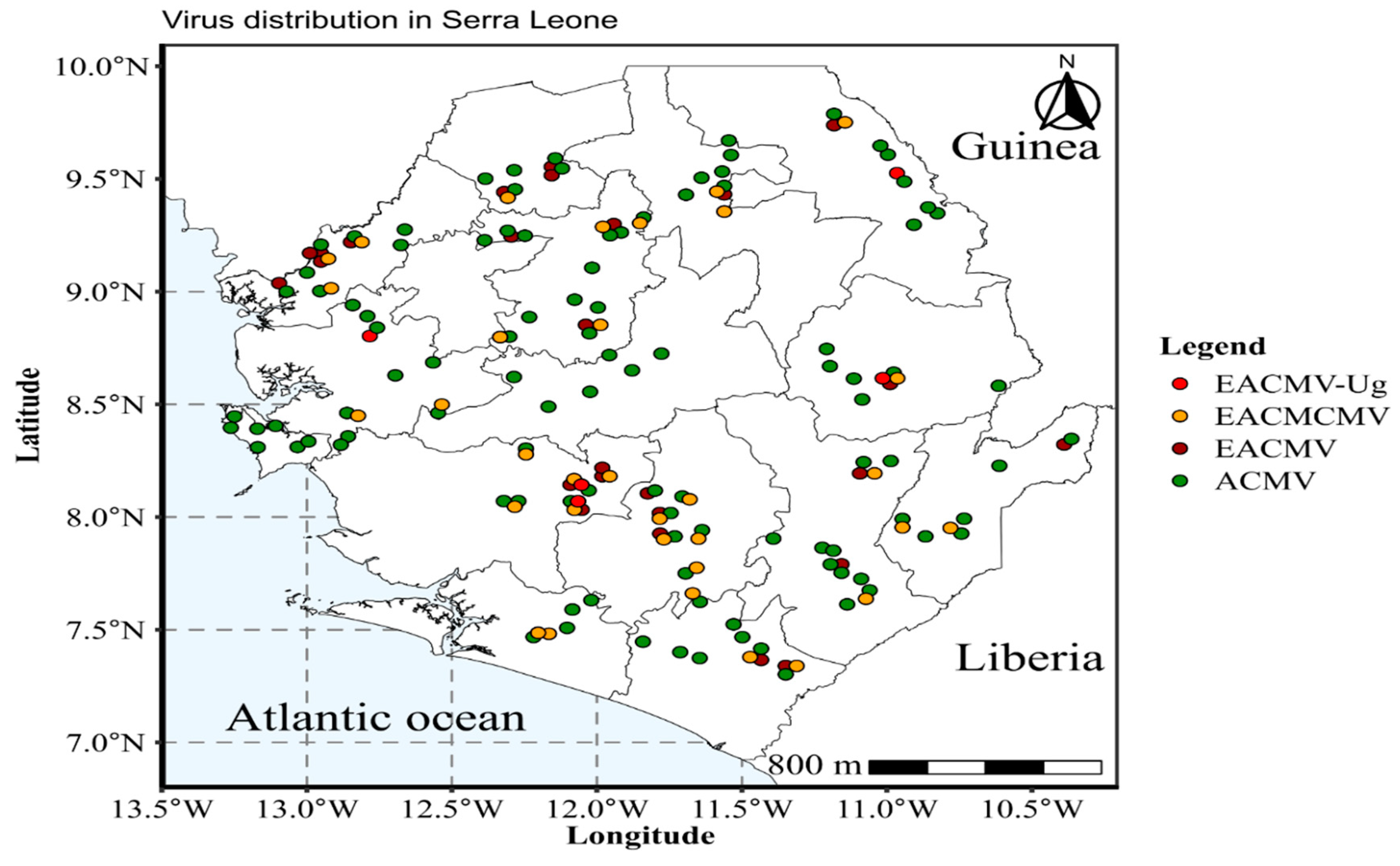

2.2. Molecular Detection and Distribution of Cassava Begomoviruses in Sierra Leone

2.3. Confirmation of CMGs Identity by Sequencing

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

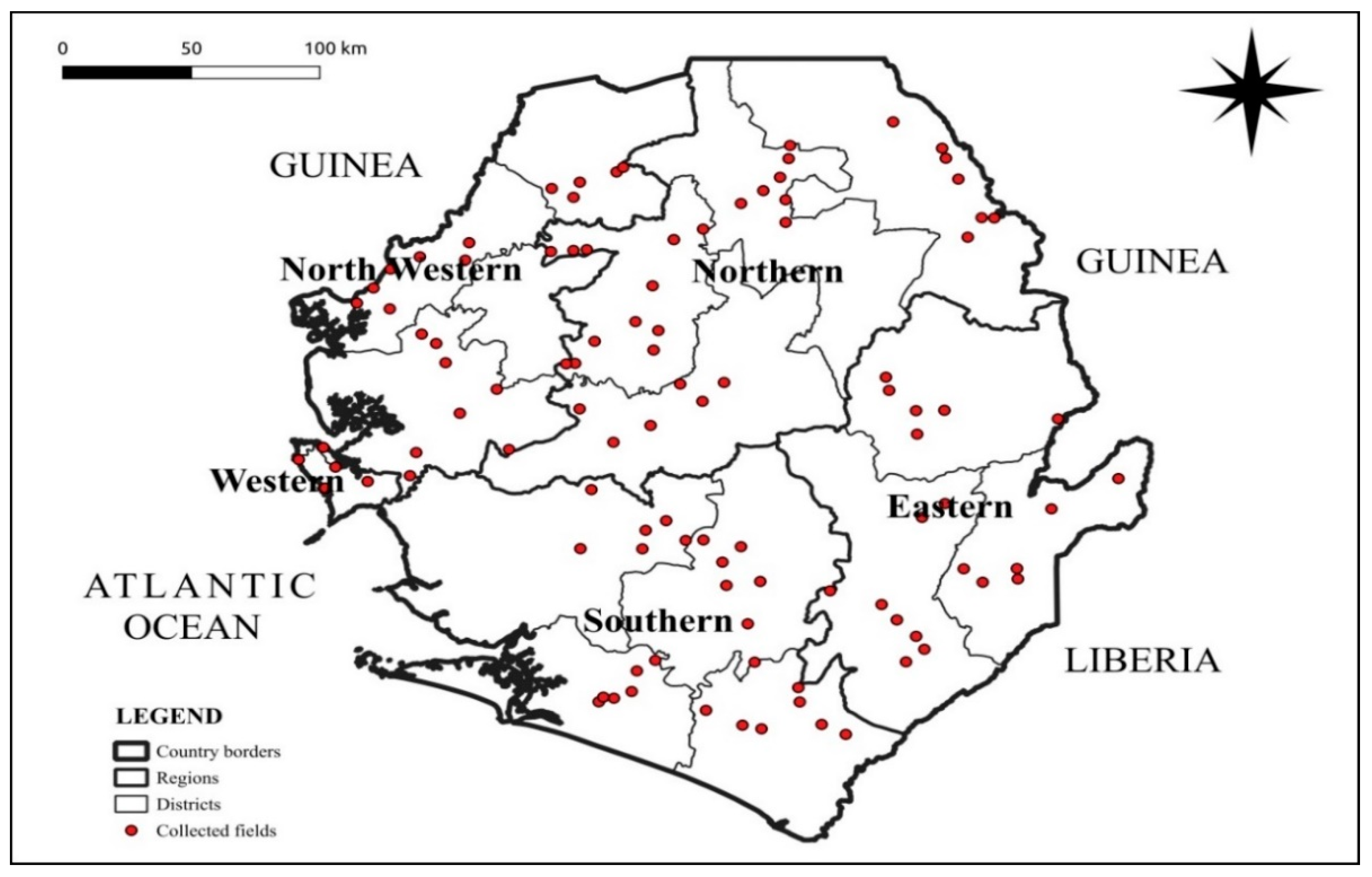

4.1. Description of the Study Area

4.2. Survey Design

4.3. Field Data Collection and Storage

4.4. Molecular Detection of Cassava Begomoviruses

4.5. Data Analysis

4.5.1. Phenotypic Analysis

4.5.2. Molecular Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACMV | African Cassava Mosaic Virus |

| CMD | Cassava Mosaic Disease |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| EACMV | East African Cassava Mosaic Virus |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Ogero, K.O.; Mburugu, G.N.; Mwangi, M.; Ombori, O.; Ngugi, M. In vitro micropropagation of cassava through low cost tissue culture. Asian J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 4, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Nassar, N.M.A.; Ortiz, R. A review on cassava improvement: challenges and impacts. J. Agric. Sci. 2007, 145, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakelana, Z.; Boykin, L.M.; Mahungu, N.; Mavila, N.; Magole, M.; Nduandele, N.; Makuati, L.; Ndomateso, T.; Monde, G.; Pita, J.; Lema, M.L.; Tshilenge, K. First report and preliminary evaluation of cassava root necrosis in Angola. Intern. J. Agric. Environ. Biores. 2019, 4, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Legg, J.P.; Jeremiah, S.C.; Obiero, H.M.; Maruthi, M.N.; Ndyetabula, I.; OkaoOkuja, G.; Bouwmeester, H.; Bigirimana, S.; Tata-Hangy, W.; Gashaka, G.; Mkamilo, G.; Alicai, T.; Lava Kumar, P. Comparing the regional epidemiology of the cassava mosaic and cassava brown streak virus pandemics in Africa. Virus Res. 2011, 159, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, S.; Koerbler, M.; Stein, B.; Pietruszka, A.; Paape, M.; Butgereitt, A. Analysis of cassava brown streak viruses reveals the presence of distinct virus species causing cassava brown streak disease in East Africa. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicai, T.; Omongo, C.A.; Maruthi, M.N.; Hillocks, R.J.; Baguma, Y.; Kawuki, R.; Bua, A.; Otim-Nape, G.W.; Colvin, J. Re-emergence of Cassava Brown Streak Disease in Uganda. Plant Disease 2007, 91, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samura, A.E.; Massaquoi, F.B.; Mansaray, A.; Kumar, P.L.; Koroma, J.P.C.; Fomba, S.N.; Dixon, A. Status and diversity of the cassava mosaic disease causal agents in Sierra Leone. Intern. J. Agric. Forestry 2014, 4, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Pan, L.L.; Bouvaine, S.; Fan, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, S.S.; Seal, S.; Wang, X.W. Differential transmission of Sri Lankan cassava mosaic virus by three cryptic species of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci complex. Virol. 2020, 540, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoroge, M.K.; Mutisya, D.L.; Miano, D.W.; Kilalo, D.C. Whitefly species efficiency in transmitting cassava mosaic and brown streak virus diseases. Cogent Biol. 2017, 3, 1311499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthi, M.N.; Hillocks, R.J.; Mtunda, K.; Raya, M.D.; Muhanna, M.; Kiozia, H.; Rekha, A.R.; Colvin, J.; Thresh, J.M. Transmission of cassava brown streak virus by Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius). J. Phytopathol. 2005, 153, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikoti, P.C.; Tembo, M.; Chisola, M.; Ntawuruhungu, P.; Ndunguru, J. Status of cassava mosaic disease and whitefly population in Zambia. African J. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 2539–2546. [Google Scholar]

- Thresh, J.M.; Cooter, R.J. Strategies for controlling cassava mosaic virus disease in Africa. Review Article. Plant Pathol. 2005, 54, 587–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sseruwagi, P.; Sserubombwe, W.S.; Legg, J.P.; Ndunguru, J.; Thresh, J.M. Methods of surveying the incidence and severity of cassava mosaic disease and whitefly vector populations on cassava in Africa: a review. Virus Res. 2004, 100, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo-Bellido, A.; Hoyer, J.S.; Dubey, D.; Jeannot, R.B.; Duffy, S. Interspecies recombination has driven the macroevolution of cassava mosaic begomoviruses. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e00541–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthi, M.N.; Seal, S.; Colvin, J.; Briddon, R.W.; Bull, S.E. East African cassava mosaic Zanzibar virus – a recombinant begomovirus species with a mild phenotype. Arch. Virol. 2004, 149, 2365–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monde, G.; Walangululu, J.; Winter, S.; Bragard, C. Dual infection by cassava begomoviruses in two leguminous species (Fabaceae) in Yangambi, northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Arch. Virol. 2010, 155, 1865–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, B.L.; Fauquet, C.M. Cassava mosaic geminiviruses: actual knowledge and perspectives. Mol. Plant Pathol 2009, 10, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndunguru, J.; Legg, J.P.; Aveling, T.A.S.; Thompson, G.; Fauquet, C.M. Molecular biodiversity of cassava begomoviruses in Tanzania: evolution of cassava geminiviruses in Africa and evidence for East Africa being a center of diversity of cassava geminiviruses. Virol. J. 2005, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyo, O.A.; Koerbler, M.; Dixon, A.G.O.; Atiri, G.I.; Winter, S. Molecular variability and distribution of cassava mosaic begomoviruses in Nigeria. J. Phytopathol. 2005, 153, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Were, H.K.; Winter, S.; Maiss, E. Distribution of begomoviruses infecting cassava in Africa. J. Plant Pathol. 2003, 85, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Samura, A.E.; Kanteh, S.M.; Norman, J.E.; Fomba, S.N. Integrated pest management options for the cassava mosaic disease in Sierra Leone. Intern. J. Agric. Innov. Res. 2016, 5, 2319–1473. [Google Scholar]

- Sesay, J.V.; Ayeh, K.O.; Norman, P.E.; Acheampong, E. Shoot nodal culture and virus indexing of selected local and improved genotypes of cassava (Manihot esculenta) from Sierra Leone. Intern. J. Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. Res. 2016, 7, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sesay, J.V.; Lebbie, A.; Wadsworth, R.; Nuwamanya, E.; Bado, S.; Norman, P.E. Genetic structure and diversity study of cassava (Mannihot esculenta) germplasm for African cassava mosaic disease and fresh storage root yield. Open J Genet. 2023, 13, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combala, M.; Pita, J.S.; Tiendrebeogo, F.; Gbonamou, M.; Eni, A.O. First report of East African cassava mosaic virus-Uganda (EACMV-Ug) infecting cassava in Guinea, West Africa. New Dis. Rep Submitted. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pita, J.S.; Fondong, V.N.; Sangare, A.; Otim-Nape, G.W.; Ogwal, S.; Fauquet, C.M. Recombination, pseudorecombination and synergism of geminiviruses are determinant keys to the epidemic of severe cassava mosaic disease in Uganda. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valam-zango, A.; Zinga, I.; Hoareau, M.; Mvila, A.C.; Semballa, S.; Lett, J.M. First report of cassava mosaic geminiviruses and the Uganda strain of east african cassava mosaic virus (EACMV-UG) associated with cassava mosaic disease in Equatorial Guinea. New Dis. Rep. 2015, 32, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiendrébéogo, F.; Lefeuvre, P.; Hoareau, M.; Traoré, V.S.E.; Barro, N.; Reynaud, B.; Traoré, A.S. Occurrence of East African cassava mosaic virus -Uganda (EACMV-UG) in Burkina Faso. Plant Pathol. 2009, 58, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chikoti, P.C.; Peter, S.; Mulenga, R.M.; Tembo, M. Cassava mosaic disease: a review of a threat to cassava production in Zambia. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 101, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anani, J.; Serge, S.; Pita, J.S.; Hound, S.E. Cassava mosaic disease (CMD) in Benin: Incidence, severity and its whitefly abun- dance from field surveys in 2020. Crop Prot. 2022, 158, 106007. [Google Scholar]

- Harimalala, M.; Chiroleu, F.; Giraud-Carrier, C.; Hoareau, M.; Zinga, I.; Randriamampianina, J.A.; Velombola, S.; Ranomenja-nahary, S.; Andrianjaka, A.; Reynaud, B.; Lefeuvre, P. , Lett, J.M. Molecular epidemiology of cassava mosaic disease in Madagascar. Plant Pathol. 2014, 64, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houngue, J.A.; Pita, J.S.; Habib, G.; Cacaï, T.; Zandjanakou-tachin, M.; Abidjo, E.A.E.; Ahanhanzo, C. Survey of farmers’ knowledge of cassava mosaic disease and their preferences for cassava cultivars in three agro-ecological zones in Benin. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eni, A.O.; Efekemo, O.P.; Onile-ere, O.A.; Pita, J.S. South west and north central Nigeria: Assessment of cassava mosaic disease and field status of African cassava mosaic virus and East African cassava mosaic virus. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2021, 178, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busogoro, J.P.; Masquellier, L.; Kummert, J.; Dutrecq, O.; Lepoivre, P.; Jijakli, M.H. Application of a simplified Molecular protocol to reveal mixed infections with begomoviruses in cassava. J. Phytopathol. 2008, 457, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Robinson, D.J.; Harrison, B.D. Types of variation in DNA-A among isolates of East African cassava mosaic virus from Kenya, Malawi and Tanzania. J. Gen. Virol. 1998, 1998. 79, 2835–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soro, M.; Tiendrébéogo, F.; Pita, J.S.; Traoré, E.T.; Somé, K.; Tibiri, E.B.; Néya, J.B.; Mutuku, J.M.; Simporé, J.; Koné, D. Epidemiological assessment of cassava mosaic disease in Burkina Faso. Plant Pathol. 2021, 70, 2207–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IITA (International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, (1990). Cassava in Tropical Africa, A reference manual. IITA, Ibadan, Nigeria. 176pp.

- Permingeat, H.R.; Romagnoli, M.V.; Sesma, J.I.; Vallejos, R.H. A simple method for isolating DNA of high yield and quality from cotton (shape Gossypium hirsutum L.) leaves. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep 1998, 16, 89–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matic, S.; da Cunha, A.T.P.; Thompson, J.R.; Tepfer, M. An analysis of viruses associated with cassava mosaic disease in three Angolan provinces. J. Plant Pathol http://www.jstor.org/stable/45156055. 2012, 94, 443–450. [Google Scholar]

- Alabi, O.J.; Kumar, P.L.; Naidu, R.A. Multiplex PCR method for the detection of African cassava mosaic virus and East African cassava mosaic Cameroon virus in cassava. J. Virol. Methods 2008, 154, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Chetvernin, V.; Tatusova, T. Improvements to pairwise sequence comparison (PASC): a genome-based web tool for virus classification. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 3293–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Number of samples |

Status of samples |

Positive samples |

Negative samples |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Detection of ACMV |

Detection of EACMV | Detection of ACMV/ EACMV | Detection of Cameroon variant | |||

| 320 CMD | 230 | 4 | 58 | 43 | 28 | |

| 426 | 106 Symptomless | 13 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 87 |

| Total | 243 | 4 | 64 | 48 | 115 | |

|

Region |

Tested samples |

Positive samples |

ACMV-single infection | EACMV-single infection | Mixed infection (ACMV & EACMV) | EACMV Cameroon variant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | N | % | n | % | |||

| South | 112 | 73 | 47 | 64.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 26 | 35.6 | 26 | 100.0 |

| East | 81 | 68 | 53 | 77.9 | 1 | 1.5 | 14 | 20.6 | 8 | 53.3 |

| North | 110 | 81 | 71 | 87.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 12.3 | 6 | 60.0 |

| Northwest | 79 | 60 | 45 | 75.0 | 3 | 5.0 | 12 | 20.0 | 8 | 53.3 |

| West | 44 | 29 | 27 | 93.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 6.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 426 | 311 | 243 | 78.1 | 4 | 1.3 | 64 | 20.6 | 48 | 70.6 |

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Target region | Expected size (bp) | Virus species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSP001 | ATGTCGAAGCGACCAGGAGAT | DNA-A (CP) | 783 | ACMV | Pita et al. [25] |

| JSP002 | TGTTTATTAATTGCCAATACT | ||||

| ACMBVF | TCGGGAGTGATACATGCGAAGGC | DNA-B (BV1/BC1) | 628 | ACMV | Matic et al. [39] |

| ACMBVR | GGCTACACCAGCTACCTGAAGCT | ||||

| WAVE-508F | AAGGCCCATGTAAGGTCCAG | AV1/AC3 | 800 | ACMV | WAVE |

| WAVE-1307R | GAAGGAGCTGGGGATTCACA | ||||

| WAVE-177F | GATCTGCGGGCCTATCGAAT | BV1 | 800 | ACMV | WAVE |

| WAVE-197R | TTCACGCTGTGCAATACCCT | ||||

| WAVE-370F | ACAGCCCATACAGGAACCGT | AV1/AC3 | 1000 | ACMV | WAVE |

| WAVE-1369R | CGACCATTCCTGCTGAACCA | ||||

| WAVE-982F | TTCGTGTCATCTGCAGGAGA | BV1/BC1 | 800 | ACMV | WAVE |

| WAVE-1781R | GTACCATGGCAGCTGCTGTA | ||||

| JSP001 | ATGTCGAAGCGACCAGGAGAT | DNA-A (CP) | 780 | EACMV | Pita et al. [25] |

| JSP003 | CCTTTATTAATTTGTCACTGC | ||||

| CMBRepF | CRTCAATGACGTTGTACCA | DNA-A (AC1) | 650 | EACMV | Alabi et al. [40] |

| EACMVRepR | GGTTTGCAGAGAACTACATC | ||||

| WAVE-EA1875F | TGTACCAGGCGTCGTTTGAA | AC1 | 800 | EACMVCM | WAVE |

| WAVE-E2674R | TGTCCCCCGATCCAAAACG | ||||

| WAVE-EB1869F | TTCCAAGGGGAGGGTTCTGA | BC1 | 800 | EACMV | WAVE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).