1. Introduction

Australia is a global center of orchid biodiversity. Of the 29,524 accepted orchid taxa [

1], approximately 1,700 are indigenous to Australia [

2]. Wild orchids face numerous threats, primarily habitat loss due to human activities and climate change. Additional threats include plant removal for collections, the decline of symbiotic pollinator species and mycorrhizal fungi, destruction by animals, competition from invasive weeds, and damage caused by pests and diseases [

3,

4,

5].

The genus

Cryptostylis comprises 23 species of orchids with a predominantly Southern Hemisphere distribution. The greatest number of species occurs in the Philippines, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea (World Checklist of Vascular Plants, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2024). Genetic analysis of

Cryptostylis species from Australia and Asia supports an Australian origin for the genus, followed by a single dispersal event to Asia and subsequent speciation [

6]. Of the five

Cryptostylis species indigenous to Australasia, four are found in eastern Australia and New Zealand, while one,

Cryptostylis ovata, is confined to southern Western Australia [

7]. Notably,

C. ovata is the only evergreen orchid among the approximately 400 terrestrial orchid taxa indigenous to Western Australia; all others are deciduous, surviving much of the year as underground bulbs or tubers.

Viruses infecting members of the Orchidaceae in Australia, as with the flora generally, are poorly studied. While many virus species identified from Australian orchids appear to have evolved on the continent, only

Divavirus and

Platypuvirus represent genera that may be endemic to Australia. Most other apparently indigenous viruses identified from Australian orchids belong to internationally distributed genera, such as

Potyvirus. Examples include

Diuris virus Y [

8] (

Potyvirus),

Donkey orchid virus A [

9] (

Potyvirus),

Caladenia virus A [

9] (

Poacevirus), and

Pterostylis blotch virus [

10] (

Orthotospovirus).

In addition to indigenous viruses, several Australian orchids are infected with exotic viruses. These viruses, which originate outside Australia, were likely introduced over the past two centuries through plants imported for agriculture, horticulture, and landscaping, and from weeds. Exotic viruses have since spilled over into native orchids. For example, isolates of bean yellow mosaic virus (BYMV,

Potyvirus) and Ornithogalum mosaic virus (OrMV,

Potyvirus) were identified in potted

Diuris magnifica orchids in Perth, W.A., and in wild

D. corymbosa orchids in remnant bushland near Brookton, Western Australia [

11]. In eastern Australia, BYMV has been detected in

Pterostylis curta and

Diuris species orchids, while OrMV, (referred to as

Pterostylis virus Y but later confirmed to be OrMV) was identified from species of

Pterostylis,

Chiloglottis,

Diuris,

Eriochilus, and

Corybas orchids [

8].

To date, no Cryptostylis species has been investigated for the presence of viruses. In this study, we tested leaf samples from wild populations of C. ovata for RNA viruses using a high-throughput sequencing approach. This method is advantageous over other virus detection techniques such as PCR- and antibody-based approaches as it does not require prior knowledge of the viruses being investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

Leaf samples were collected from 83 individual

C. ovata plants from 16 populations in southern Western Australia (

Table 1). Due to the lateral spread of

C. ovata plants through rhizomes, it was challenging to delineate individual plants. To address this, leaves spaced at least 1 m apart were considered to belong to distinct individual plants. Sampling sites included a variety of habitats, ranging from remnant roadside bushland to indigenous forests and exotic

Pinus radiata plantations. The aim was to collect samples from 10 individuals per population; however, in populations with fewer than 10 plants, one sample was collected from every available plant. Samples were taken regardless of visible symptoms of virus infection, such as chlorosis on young leaves, mosaic patterns, necrosis, or stunting.

Leaf samples were collected from 83 individual

C. ovata plants from 16 populations in southern Western Australia (

Table 1). Due to the lateral spread of

C. ovata plants through rhizomes, it was challenging to delineate individual plants. To address this, leaves spaced at least 1 m apart were considered to belong to distinct individual plants. Sampling sites included a variety of habitats, ranging from remnant roadside bushland to indigenous forests and exotic

Pinus radiata plantations. The aim was to collect samples from 10 individuals per population; however, in populations with fewer than 10 plants, one sample was collected from every available plant. Samples were taken regardless of visible symptoms of virus infection, such as chlorosis on young leaves, mosaic patterns, necrosis, or stunting.

Total RNA was extracted from 100 mg of leaf tissue using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) after grinding the samples in liquid nitrogen. To prepare for cDNA library construction, ribosomal RNA was depleted using the Ribo-Zero Plant kit, and libraries were generated with the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Plant Library preparation kit (Illumina). Paired-end high-throughput sequencing (HTS) was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 platform with 150 cycles.

Post-sequencing, TruSeq primer-adaptors were removed, and quality trimming was performed using default parameters in CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen). Reads shorter than 100 nucleotides were discarded. De novo assembly was conducted in both CLC Genomics Workbench and Geneious Prime (Biomatters). Contigs longer than 500 nucleotides were analysed using Blastn. Contigs matching viral sequences and those with no matches (referred to as orphans) were subjected to further analysis.

Orphan contigs were translated in six reading frames (three forward and three reverse). Contigs without open reading frames (ORFs) of at least 100 amino acid residues were discarded. For those with ORFs, nucleotide and amino acid sequences were analysed in Blastn or Blastp, respectively, for similarities to known sequences.

Based on HTS results, five sets of species-specific primers were synthesised for each identified virus (

Table S1). Primers were designed in Primer 3, each with a melting temperature of 60

oC.

All 83 RNA samples were then tested using these primers via RT-PCR. Amplified bands were sequenced using the Sanger method. Primer sequences were trimmed from the resulting sequences, which were then aligned against HTS-derived sequences and publicly-available sequences from GenBank using Blastn. Gaps between amplicons were filled by combining appropriate primers and performing additional Sanger sequencing. This process enabled the identification of virus-derived sequences and facilitated the assembly of complete or partial genome sequences for each virus present in infected plants.

3. Results

3.1. Plant Samples

In each population except the Bowelling-Duranillin Road population, plants appeared to be healthy, lacking symptoms typical of virus infection. At the Bowelling-Duranillin Road population, all eight plants displayed mosaic patterns and chlorotic streaking symptoms reminiscent of virus infection (

Figure 1).

3.2. Viruses

Following RNA sequencing, viruses were identified from two C. ovata populations. The eight samples tested from the Bowelling-Duranillin Road population were doubly-infected with bean yellow mosaic virus (BYMV) and Ornithogalum mosaic virus (OrMV). One of the six plants from the Devlin Rd population was infected with an isolate of BYMV. No viruses were identified from the other C. ovata plants tested.

3.3. Sequence Analysis

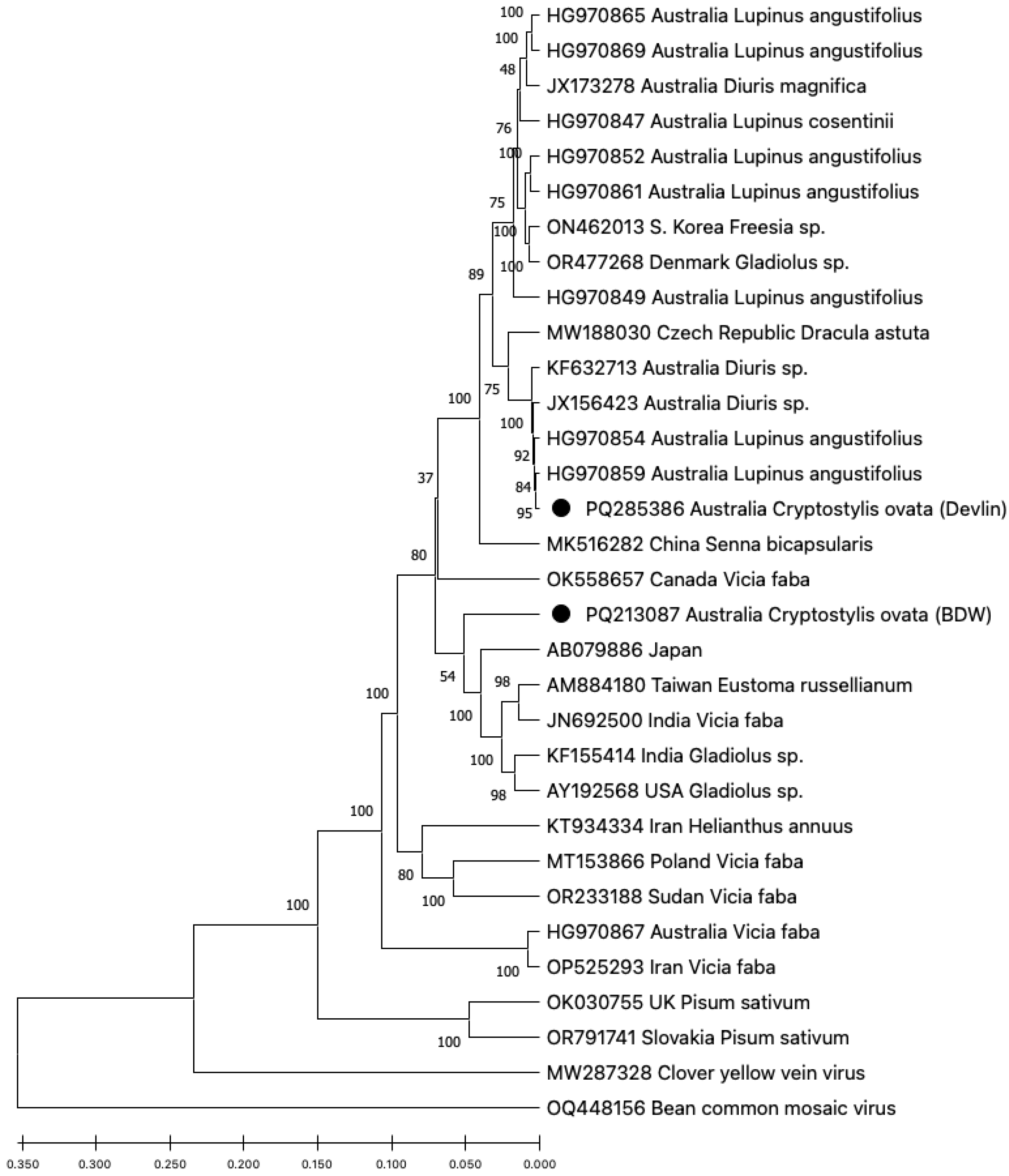

Alignment of the eight BYMV sequences from the Bowelling-Duranillin Road population revealed that they were identical. This isolate was named BYMV-BDW. One of the samples collected from the Devlin Rd population was infected with a distinct isolate of BYMV. (

Figure 2).

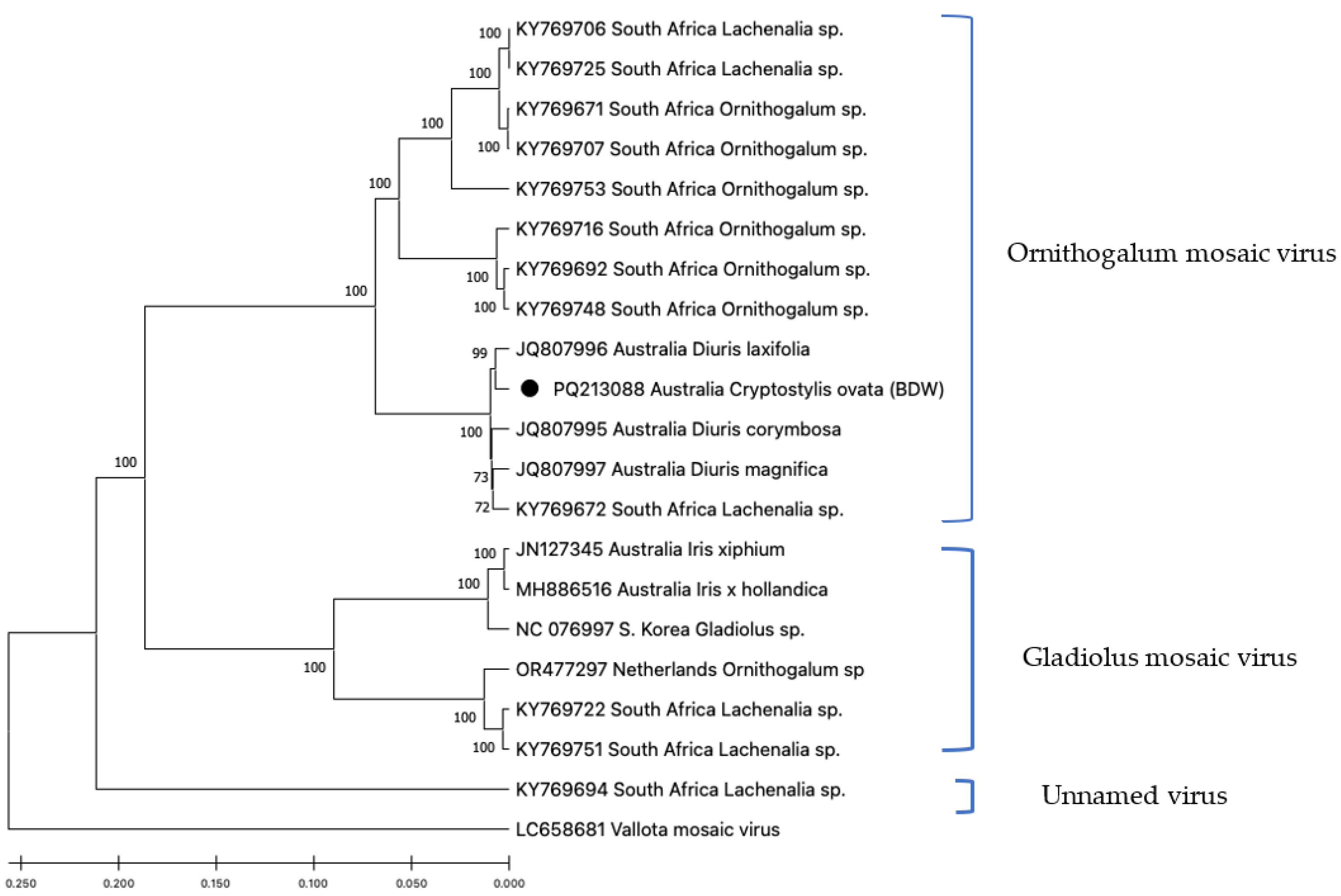

The eight OrMV sequences from the the Bowelling-Duranillin Road population were identical, and this isolate was named OrMV-BDW (

Figure 3).

The complete genome sequence of BYMV-BDW was 9481 nt, encoding 3056 aa, while isolate BYMV-Devlin was incomplete at 8387 nt at the 5’ end, encoding 2749 aa and lacking the 5’ untranslated region and the terminal region of the P1 gene. Isolates BYMV-BDW and BYMV-Devlin were not identical, sharing 91% nt and 96% aa identities over the common regions. Phylogenetic analysis of the nucleotide sequences of these two isolates with other BYMV genome sequences available from GenBank revealed that BYMV-Devlin shared 99% identities with four other BYMV isolates from W.A., two from wild symptomatic

Diuris orchids and two from

Lupinis angustifolius (narrow-leafed lupin) plants collected from crops. In contrast, BYMV-BDW was not closely aligned with other BYMV isolates from Australia, instead sharing up to 92% identity with BYMV isolates from India, Taiwan, Japan and the USA collected from diverse hosts (

Figure 2).

The complete genome sequence of isolate OrMV-BDW was 9045 nt. OrMV-BDW shared greatest identities (98-99%) with OrMV isolates identified from indigenous

Diuris orchids from Western Australia, and also with an isolate from a wild

Lachenalia sp. plant collected in South Africa, where it is an indigenous species (

Figure 3).This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

This paper presents the first report of viruses infecting plants of the orchid C ovata. Of the sixteen Cryptostylis ovata populations tested, only two populations had plants infected with one or two viruses. The two viruses, BYMV and OrMV, have origins outside Australia. No indigenous viruses were identified.

Interestingly, the eight plants collected from the Bowelling-Duranillin Road population were all infected with identical isolates of BYMV and OrMV. This suggests that this population may either comprise a single large plant that has spread several metres in diameter, or it may comprise individuals infected with the same virus isolates through aphid vectors or through root or leaf contact.

BYMV has a broad international distribution and host range, infecting both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants over all temperate cropping regions. It poses a serious threat to leguminous crops, such as narrow-leafed lupins and clover/medic pastures in Western Australia [

12,

13] and elsewhere, as well as to floriculture crops such as

Gladiolus sp. in several countries [

14,

15]. BYMV has been reported from a range of wild and cultivated orchids, including

Vanilla and other orchids in French Polynesia [

16],

Masdevallia orchids from the USA, and

Calanthe orchids from Japan [

17]. Like other potyviruses, BYMV is transmitted horizontally by aphids, mechanically by physical contact, and via pollen, and vertically through seed in several plant species [

18,

19], although seed transmission has not been recorded in orchids.

No aphids are reported infesting the leaves of C. ovata, and, indeed, these authors have not observed this in decades of observation. However, the authors have noted aphids colonizing flowers, suggesting this may be the route through which aphids transmit viruses from source plants to C. ovata. Notably, C. ovata produces flowers in mid-summer, after some major BYMV sources, such as narrow-leafed lupin crops, have already been harvested in Western Australia.

BYMV is a genetically diverse virus, with several groupings proposed based on nucleotide sequence phylogeny and host preferences [

20,

21,

22]. BYMV-Devlin shares greatest genetic identity with isolate BYMV-SW3.2 already described from Western Australia in wild orchids (JX156423) (

Figure 2), suggesting this strain is widespread among different hosts in the region as these two host orchids were located at least approximately 140 km apart. In the

Diuris corymbosa orchid source, BYMV-SW3.2 infection caused chlorotic leaf mottle [

11], while the

C. ovata plant infected with the near-identical isolate BYMV-Devlin appeared asymptomatic. In contrast, plants infected with BYMV-BDW exhibited strong symptoms of infection. Since Koch’s postulates were not applied, it remains unclear whether the pronounced symptoms in the Bowelling-Duranillin Road population were caused by BYMV-BDW, OrMV-BDW, or both. The BYMV-BWD sequence closely resembled the

Gladiolus hybrida isolate BYMV-M11 (AB079886) from Japan, which induced mild symptoms or no symptoms in

Nicotiana benthamiana and

Vicia faba plants [

23]. It is also possible that there are non-viral origins for the symptoms observed in the Bowelling-Duranillin Road population.

Like BYMV, OrMV is an aphid-transmitted potyvirus with a broad geographical and host range, but it appears to be restricted to monocotyledonous plants. It is a significant pathogen of floricultural crops, especially ornamental bulbous plants originating from Africa, such as

Iris,

Ornithogalum,

Lachenalia,

Sparaxis,

Gladiolus,

Tritonia, and others [

24]. OrMV was first identified in Western Australia from ornamental

Iris plants in home gardens [

9]. Species of several iridaceous genera, such as

Gladiolus,

Homeria,

Ixia,

Lachenalia, and

Freesia of southern African origin have become naturalised weeds in Western Australian bushlands [

25]. Their role as hosts for OrMV and BYMV remains untested.

The presence of close-to-identical (99%) OrMV sequences in indigenous

Diuris orchid populations in Western Australia located approximately 125 km from the BDW population, and an

Iris plant from a domestic garden in Western Australia, located approximately 230 km from the BDW population, suggest there has been a single introduction of OrMV into Western Australia, but more extensive sampling is required to confirm this. The high genetic identity (98%) between the Western Australia OrMV isolates and an isolate from a

Lachenalia plant in South Africa indicates that bulbous ornamental plants imported into Western Australia as garden plants, including several

Lachenalia species [

26], are sources of OrMV to the region. More study is required to determine if such weeds continue to host OrMV and the means by which this virus is transmitted between them, whether by feed aphid vectors or pollen carried by bees or the wind.

This study demonstrates that spillover of two exotic potyviruses to the indigenous Cryptostylis ovata orchid has occurred in Western Australia. The probable origin of OrMV lies in invasive weeds introduced into Australia as bulbous ornamental garden plants from Africa, and which are now rapidly invading bushlands. The origin of BYMV could be in seeds of leguminous crop and pasture species, as well as in invasive garden plants. Invasive weeds not only compete with indigenous species for resources such as space, water and nutrients, but also likely serve as reservoirs for damaging viruses. Further research is needed to understand the roles of such weeds in viral spillovers to indigenous species, including orchids, in Australian bushlands.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Primer pairs used to confirm presence of bean yellow mosaic virus (primer names beginning BYMV) and Ornithogalum mosaic virus (primer names beginning OrMV) by PCR. The primer names also contain information on the name of the genes to which they bind and whether they are forward (F) or reverse (R) primers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W., H.L. and S.H.K.; methodology, S.W., H.L., and S.H.K.; software, S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W., H.L and S.H.K.; funding acquisition, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Australian Orchid Foundation, grant number 340/21.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Nucleotide sequences generated from this study are available from GenBank using the accession codes provided.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Sherine Lim and Carissa Lim in assisting with sample collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pérez-Escobar, O.A.; Bogarín, D.; Przelomska, N.A.; Ackerman, J.D.; Balbuena, J.A.; Bellot, S.; Bühlmann, R.P.; Cabrera, B.; Cano, J.A.; Charitonidou, M. and Chomicki, G. The origin and speciation of orchids. New Phytologist 2024, 242, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones DL (2024) A complete guide to native orchids of Australia. Revised 3rd edn. New Holland Publishers, Sydney, Australia, 2024; pp. 12-54.

- Swarts, N.D.; Dixon, K.W. Terrestrial orchid conservation in the age of extinction. Ann bot 2009, 104, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brundrett, M.C. Using vital statistics and core-habitat maps to manage critically endangered orchids in the Western Australian wheatbelt. Aust J Bot 2016, 64, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowska, M.; Michalska, E. The effect of global warming on the Australian endemic orchid Cryptostylis leptochila and its pollinator. Plos One 2023, 18(1), p.e0280922.

- Weinstein, A.M. Pollination ecology of Australian sexually deceptive orchids with contrasting patterns of pollinator exploitation. PhD, The National University of Australia, Canberra, 2021.

- Arifin, A.R.; Phillips, R.D.; Weinstein, A.M.; Linde, C.C. Cryptostylis species (Orchidaceae) from a broad geographic and habitat range associate with a phylogenetically narrow lineage of Tulasnellaceae fungi. Fung Biol 2022, 126, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, A.; Mackenzie, A.; Blanchfield, A.; Cross, P.; Wilson, C.; Elliot, K.; Nightingale, M.; Clements, M. Viruses of orchids in Australia: Their identification, biology and control. Aust Orchid Rev 2000, 65, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, S.J.; Tan, A.J.Y.; Li, H.; Dixon, K.W.; Jones, M.G.K. Caladenia virus A, an unusual new member of the family Potyviridae from terrestrial orchids in Western Australia. Arch Virol 2012, 157, 2447–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, H.Y.; Clements, M.A.; Mackenzie, A.M.; Dietzgen, R.G.; Thomas, J.E.; Geering, A.D. Viruses infecting greenhood orchids (Pterostylidinae) in Eastern Australia. Viruses 2022, 14, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, S.J.; Li, H.; Dixon, K.W.; Richards, H.; Jones, M.G.K. Exotic and indigenous viruses infect wild populations and captive collections of temperate terrestrial orchids (Diuris Species) in Australia. Virus Res 2013, 171, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Jones, R.A.C. Distribution and incidence of necrotic and non-necrotic strains of bean yellow mosaic virus in wild and crop lupins. Aust J Agric Res 1999, 50, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.A. Virus diseases of perennial pasture legumes in Australia: incidences, losses, epidemiology, and management. Crop Past Sci 2013, 64, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, M.; Ram, R.; Zaidi, A.A.; Garg, I.D. Status of bean yellow mosaic virus on Gladiolus. Crop Prot 2002, 21, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, C.; Raj, R.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, S.; Raj, S.H.K. Sequence analysis of six full-length bean yellow mosaic virus genomes reveals phylogenetic diversity in India strains, suggesting subdivision of phylogenetic group-IV. Arch Virol 2018, 163, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agronomique, P.; Tahiti, F.P. Virus infections of Vanilla and other orchids in French Polynesia. Plant Dis 1987, 71, 1125. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, J.; Lawson, R.H. A strain of bean yellow mosaic virus is aphid-transmitted from orchid. In Proceedings of the VII International Symposium on Virus Diseases of Ornamental Plants, Sanremo, Ital, (29 May 1988).

- Pathipanowat, W.; Jones, R.A.C.; Sivasithamparam, K. Studies on seed and pollen transmission of alfalfa mosaic, cucumber mosaic and bean yellow mosaic viruses in cultivars and accessions of annual Medicago species. Aust J Agric Res 1995, 46, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaya, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Yamamoto, T. Seed transmission of bean yellow mosaic virus in broad bean (Vicia faba). Japan J Phytopathol 1993, 59, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, S.J.; Coutts, B.A.; Jones, M.G.K.; Jones, R.A.C. Phylogenetic analysis of bean yellow mosaic virus isolates from four continents: relationship between the seven groups found and their hosts and origins. Plant Dis 2008, 92, 1596–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, M.A.; Coutts, B.A.; Buirchell, B.J.; Jones, R.A. Split personality of a potyvirus: to specialize or not to specialize?. PLoS One 2014, 9(8), p.e105770.

- Kaur, C.; Raj, R.; Kumar, S.; Purshottam, D.K.; Agrawal, L.; Chauhan, P.S. and Raj, S.H.K. Elimination of bean yellow mosaic virus from infected cormels of three cultivars of Gladiolus using thermo-, electro-and chemotherapy. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazono-Nagaoka, E.; Sato, C.; Kosaka, Y. Evaluation of cross-protection with an attenuated isolate of bean yellow mosaic virus by differential detection of virus isolates using RT-PCR. J Gen Plant Pathol 2004, 70, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Du, Z.; Shen, J.; Yang, H.; Liao, F. Genetic diversity and molecular evolution of Ornithogalum mosaic virus based on the coat protein gene sequence. Peer J 2018, 6, p.e4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenhouse, R.N. Fragmentation and internal disturbance of native vegetation reserves in the Perth metropolitan area, Western Australia. Landsc Urb Plan 2004, 68, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Brooks, K.; Madden, S.; Marshall, J. Control of the exotic bulb, Yellow Soldier (Lachenalia reflexa) invading a Banksia woodland, Perth, Western Australia. Ecol Manag Restor 2002, 3, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).