1. Introduction

The field of genetics and genomics has evolved greatly in the wake of ongoing technological advancements [

1,

2,

3]. Consequently, diverse methods have arisen to investigate genetic diversity. Some of these methods gain popularity and momentum only to be replaced by subsequent more effective and faster techniques, e.g. allozymes [

4], Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms (RFLPs [

5]) while some methods such as microsatellites endure the tests of time [

6,

7]. The development and subsequent availability of high-throughput sequencing methods (“next generation sequencing”- NGS) has once again changed the game for conservation genetics, providing highly informative and precise genetic information for diverse applications [

1,

3]. These methods such as SNP’s, genotyping-by sequencing (GBS), Restriction-site associated DNA sequencing (RADseq [

8]), Multiplexed ISSR genotyping-by-sequencing (MIG-seq [

9]) etc. provide invaluable insights into aspects such as population diversity, dynamics and viability, identifying taxonomic and management units, detecting local adaptation, predicting genetic effects, all of which can greatly inform conservation decisions [

1,

3,

10].

However, these high throughput NGS methods are often prohibitively expensive in developing countries due to a lack of infrastructure, skill and resources, as well as unfavourable exchange rates for equipment and consumables [

2,

11,

12]. Consequently, these countries have to resort to cheaper genetic markers [

7]. These countries are coincidentally also often biodiverse, containing disproportionately high levels of rare taxa, and experience great human or climate related pressures, further increasing extinction risks of endemic or rare species in these countries [

13].

Because of this financial and skills inequity, conservation research is not performed in areas where it is most needed [

11,

12]. Conservation spending (and budgets) correlate to the level of research performed and reduction in the rate of biodiversity loss in these countries [

12,

14]. It is thus imperative to provide support for these countries, while also investigating and implementing simpler and more cost-effective genetic methods more accessible to local researchers and institutions [

2,

12].

One such method is Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSRs [

15,

16]). ISSR markers are generated from PCR reactions using flanking microsatellite regions as priming sites [

15,

16]. The ubiquity and variability of microsatellites in eukaryotes mean many priming sites are available throughout the genome leading to increased resolution and almost full genome coverage, all whilst requiring no

a priori sequence information [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The main benefits of ISSRs are their cost, speed and simplicity compared to other methods [

6,

17,

23,

24]. Moreover, the use of PCR allows the rapid generation of large volumes of markers from only a small amount of DNA [

20,

24]. ISSRs are also highly sensitive markers suitable for discriminating closely related species and investigating intraspecies variation [

21,

25,

26]. ISSRs thus offer a higher degree of resolution compared to other “fingerprinting” molecular methods [

21]. Compared to RFLPs and RAPDs, ISSR markers give similar results but produce more extensive and informative datasets for less cost, time, and labour [

17,

24]. In contrast, methods, such as AFLP markers, although more reproducible and accurate, are more costly and complicated [

17]. ISSRs are also more reproducible than RAPD markers [

17], but are less reproducible than RFLPs [

24]. ISSRs are thus very useful molecular markers in ecological, genetic diversity and even systematic studies due to their hypervariable nature and low cost [

20]. As a consequence of these factors, ISSR’s are used widely in developing countries for a range of purposes. A search of the SCOPUS data base (11 March 2024) using the search terms (“inter AND simple AND sequence AND repeat*) OR ISSR*” found 7852 publications. An analysis of the author affiliations of these papers using VOSViewer ver. 1.6.15 [

27] indicated that the vast majority of these authors or co-authors are from developing countries, many of which are also mega-biodiverse (

Table 1).

ISSRs have proven valuable in a wide range of applications including hybridisation and taxonomic studies [

21,

25], phylogeny reconstruction [

28], population genetic studies [

29,

30,

31,

32], demographics [

33], the investigation of the mating systems and reproduction of plants [

34], sex determination [

35,

36], distinguishing ecotypes [

37], as well as studies on crops and crop relatives and medicinal plants [

38,

39,

40,

41] and identifying markers for traits such as toxin production or phenotypes [

35,

36,

42]. Of particular relevance to our study, this method has also been applied to rare and endangered or endemic species [

29,

31,

43,

44,

45] as well as widespread and common species [

46].

The vast majority of ISSR studies utilise conventional agarose gel visualisation of banding patterns, a very cheap and readily available technology, which perhaps explains the extensive use of this method in developing countries. However, another benefit to ISSR fingerprinting is that the primers can be modified by labelling with fluorescent dyes that allow for the automated detection of bands using DNA sequencing machines [

47]. This modification of the primers and use of slightly more costly automated detection systems provides greater sensitivity and resolution of bands coupled with the ability to accurately size much larger ISSR fragments, resulting in larger datasets and more accurate fragment sizing potentially able to differentiate fragments with as little difference as a single nucleotide [

48,

49]. Owing to the higher sensitivity of the automated process, much larger datasets are produced, but possibly with lower marker informativeness [

37]. However, despite these advantages, it has not been widely used. Automated ISSR fingerprinting has, however, been used effectively in plantains (

Musa L. sp. [

37]), cotton (

Gossypium L. [

50]),

Vachellia karroo (Hayne) Banfi & Galasso [

51], the endemic and widespread species within

Tolpis Adans. (Asteraceae [

47]) and endangered

Faucaria tigrina Schwantes (Aizoaceae [

45]).

Based on the above considerations and the merits of ISSR’s, this study employs automated ISSR fingerprinting to determine the genetic diversity of the African cycad

Encephalartos eugene-maraisii I. Verd. species complex and to ascertain whether genetic diversity corresponds to currently defined taxonomic groups in this complex. Of relevance to this study is the fact that ISSRs have previously been used in cycads for a wide range of applications (

Table S1), but their use along with automated fragment detection has yet to be applied to cycads.

1.1.The conservation status of cycads in Africa – Encephalartos as a case study.

The African cycad genus

Encephalartos Lehm. is considered the most threatened cycad genus globally and the most threatened group of organisms in South Africa, with 12 of 37 (32%) species in South Africa listed as Critically Endangered (compared to the global average of 17% in cycads), and an additional four which are endangered [

52,

53]. Moreover, the five cycad species that are listed as Extinct in the Wild by the IUCN are from the genus

Encephalartos, all of which once occurred within the borders of South Africa (

E. brevifoliolatus Vorster, E. nubimontanus P.J.H.Hurter

, E. woodii Sander

., and

E. heenanii R. A. Dyer) or landlocked Eswatini (= Swaziland,

E. relictus P.J.H.Hurter,). Additionally, South Africa is an important cycad diversity hotspot and site of endemism containing 58% of

Encephalartos species, of which 80% are endemics [

54,

55,

56].

This South African cycad extinction crisis [

55,

57,

58] may result in South Africa losing 50% of its species within 2-10 years [

59]. This extinction is driven by poaching for the ornamental plant trade, the harvest of specimens for medicinal, recreational, and magical purposes [

52,

53,

54,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63], as well as pathogens [

64], herbivory [

65], and pollinator extinction [

56,

66]. Moreover climate change, leading to greater environmental stochasticity and subsequent susceptibility to pests and pathogens [

13,

65,

67] also poses a threat, as well as habitat fragmentation and destruction, the spread of alien invasive species and reproductive failure [

54,

55,

68]. Conservation of this group has thus never been more urgent.

Despite much activity in South African cycad conservation and research [

52,

55,

60,

62,

69,

70], there remains limited knowledge about even the most basic aspects of cycad biology or population size and trends for many species [

54,

71,

72,

73]. In addition, research directed at assessing the genetic diversity of South African cycads is required, as little work has been done on these taxa [

74,

75]. Moreover, the taxonomic relationships between some species, especially among closely related taxa, need to be resolved, thereby allowing the correct designation of conservation status for these taxonomic units [

54,

71,

76,

77,

78]. Much of the taxonomically unresolved portions of the genus occur within species complexes containing recently diverged taxa [

54,

55].

Species complexes comprise groups of closely related species which often co-occur or have close geographical proximity. Owing to morphological and genetic similarities, members of these complexes are often difficult to distinguish, which can lead to unclear or biased species delimitation or incorrect designation of conservation units [

78]. These complexes are additionally enigmatic in that morphological distinctness does not necessarily correlate with genetic differentiation of species, with the opposite occasionally true [

79]. Several examples of cycad species complexes exist [

80,

81,

82]. In the genus

Encephalartos, such complexes include the

E. hildebrandtii A.Braun & C.D.Bouché species complex of East Africa [

83], as well as a group of mostly glaucous

Encephalartos species in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa [

79], and the glaucous cycads comprising the

Encephalartos eugene-maraisii I. Verd. complex occurring in the northern escarpment of South Africa, comprising six species [

84].

1.1.1. The Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex

The

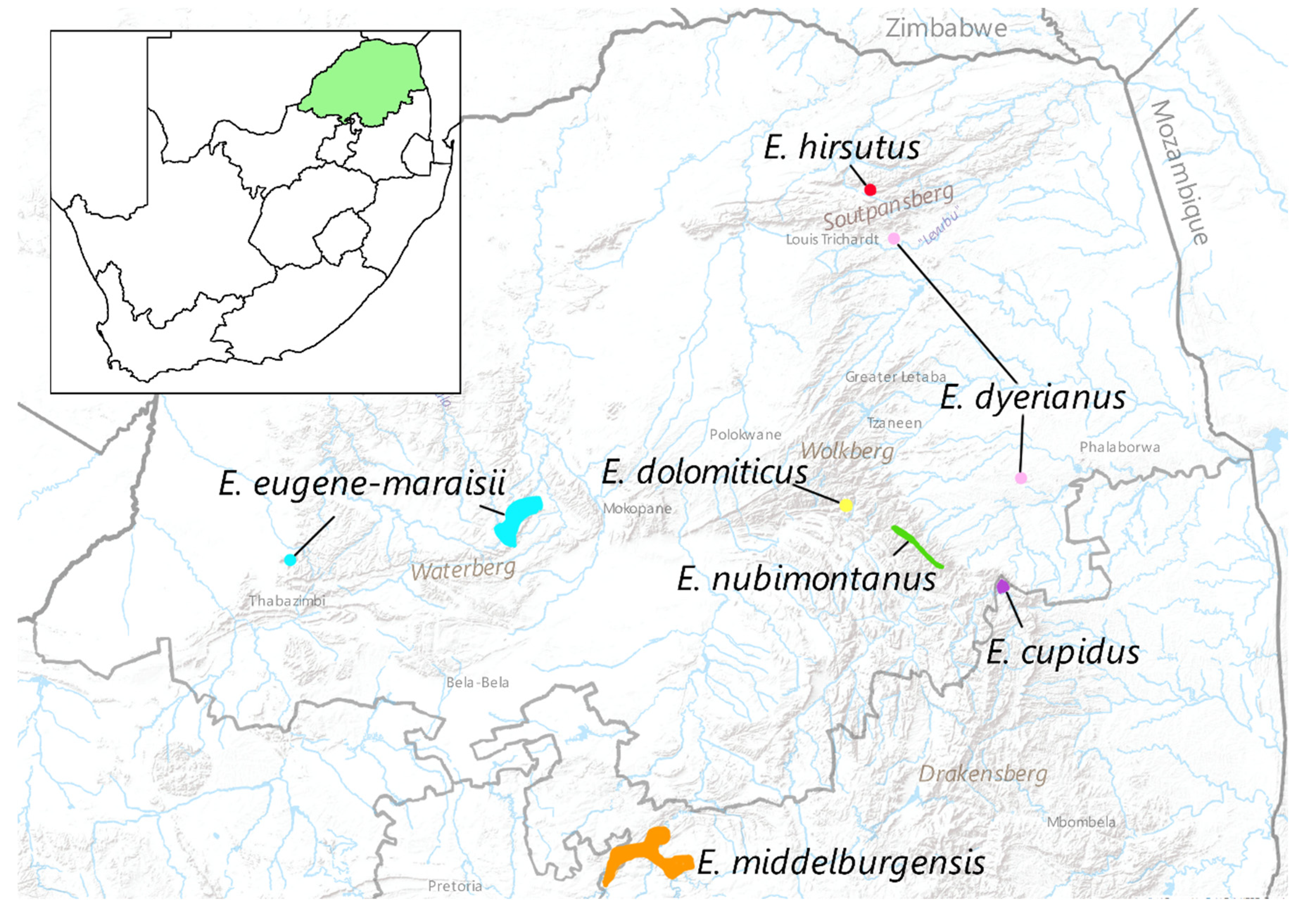

Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex is a group of closely related cycads with glaucous foliage occurring mainly in the Limpopo and Mpumulanga provinces of South Africa (

Figure 1). Members of the complex comprise

E. eugene-maraisii, E. dolomiticus Lavranos & D.L.Goode

, E. middelburgensis Vorster, Robbertse & S.van der Westh.

, E. dyerianus Lavranos & D.L.Goode

, E. cupidus R.A. Dyer,

E. nubimontanus P.J.H.Hurter, and potentially

E. hirsutus P.J.H.Hurter (

Table S2). In this complex, the taxonomic relationships are uncertain and there is considerable morphological variation within the complex, with some species having as many as eleven different variants recognised (formally and informally) by collectors and growers [

85,

Table S2]. Within this pool of variation, there may lie undescribed species, or alternatively, species which require merging. Given the tendency among cycad taxonomists for excessive subdivision of species [

86,

87], many taxa in such complexes may be possible artefacts of over-ambitious taxonomy.

Broad taxonomic and phylogenetic studies on

Encephalartos place the

E. eugene-maraisii complex into a single clade with little to no resolution and weak support between the member species [

76,

88,

89]. The morpho-geographical classification of

Encephalartos proposed by Vorster (2004) [

84] places the complex, with the possible inclusion of

E. hirsutus, in the same grouping. Molecular studies by Stewart et al. (2023) [

89] and Mankga et al. (2020) [

88] supported the exclusion of

E. hirsutus from the

E. eugene-maraisii complex, but provided no further insight into the molecular or taxonomic relationships between members of the complex. Species members of this complex were not well represented in these studies comprising singletons, pairs, or being absent entirely. This likely had consequences for phylogenetic resolution for this group, particularly since these taxa are closely related [

90].

5. Conclusions

Using the automated ISSR detection method and a range of analytical approaches, we were able to distinguish some of the species within the E. eugene-maraisii complex as distinct lineages. However, we recommend additional sampling, and further optimisation of DNA extraction and PCR amplification procedures, for some of the currently recognised species, as these taxa may not warrant recognition at this rank. In addition, the use of additional primers may be necessary to improve resolution and elucidate the relationships among E. nubimontanus and E. cupidus; and the taxonomic validity of E. middelburgensis.

Our study has, moreover, highlighted the importance of using a variety of datasets and analytical methods to explore the signal in the data and to determine which datasets best suit each analysis.

Finally, we demonstrate the suitability of automated ISSR fingerprinting as a rapid, simple, and cost-effective method to investigate genetic diversity and taxonomic limits in closely related and range restricted Encephalartos species, and potentially many other taxa. This method thus holds great potential in the application of conservation genetics and taxonomy of all taxa, for scientists in developing countries.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. Conceptualization, N.P.B; methodology, D.M and N.P.B; software, D.M.; validation, A.W.F., D.M. and N.P.B.; formal analysis, D.M.; investigation, D.M.; resources, A.W.F. and N.P.B..; data curation, D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.; writing—review and editing, A.W.F. and N.P.B.; visualization, D.M.; supervision, N.P.B. and A.W.F.; project administration, A.W.F. and N.P.B.; funding acquisition, D.M and N.P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Map of the Limpopo province of South Africa showing the approximate location of the six members of the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex as well as E. hirsutus.

Figure 1.

Map of the Limpopo province of South Africa showing the approximate location of the six members of the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex as well as E. hirsutus.

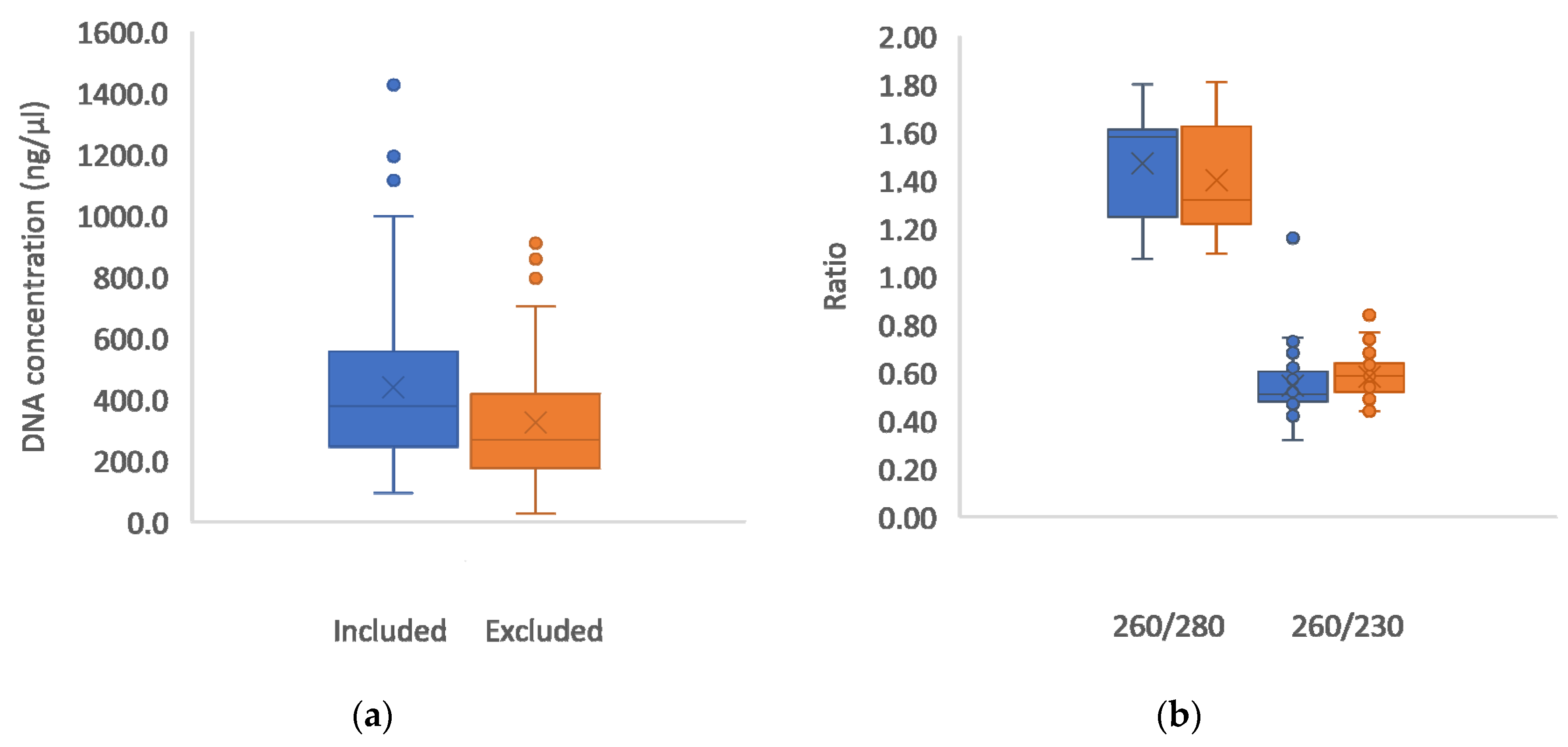

Figure 2.

Boxplots showing the Nanodrop readings for DNA concentration in ng/µl (a) and DNA fluorescence ratios indicating purity (b), in samples which were included in the study (blue plots) and those excluded (orange plots) due to unsuccessful PCR amplification. Means are denoted by X and medians by horizontal lines inside the boxes. Outliers are denoted by dots.

Figure 2.

Boxplots showing the Nanodrop readings for DNA concentration in ng/µl (a) and DNA fluorescence ratios indicating purity (b), in samples which were included in the study (blue plots) and those excluded (orange plots) due to unsuccessful PCR amplification. Means are denoted by X and medians by horizontal lines inside the boxes. Outliers are denoted by dots.

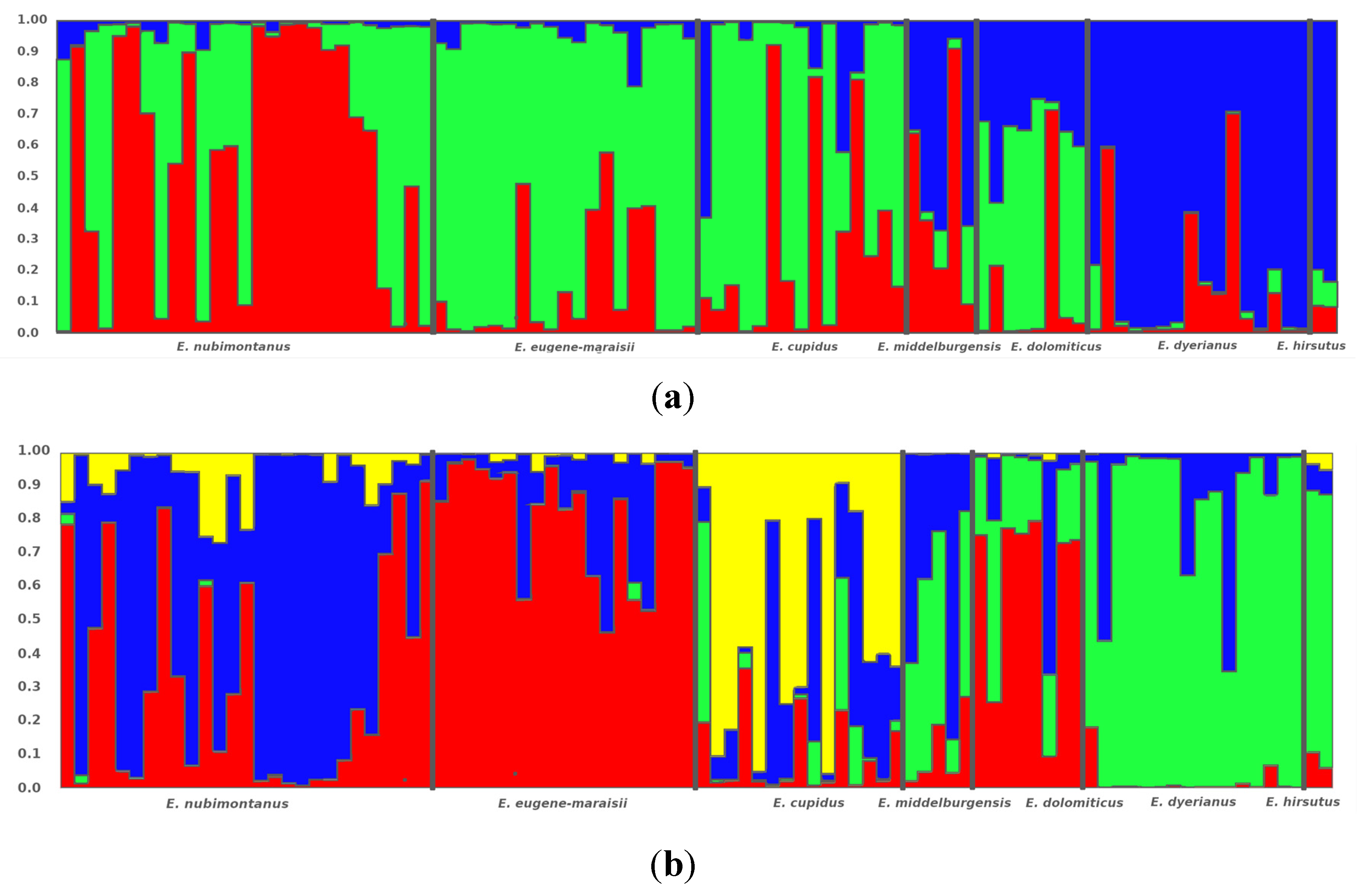

Figure 3.

STRUCTURE bar plots showing the proportion of membership of samples assigned to the optimum K within the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex. Results are based on ISSR fragments scored at a 50 relative fluorescence unit (rfu) cut-off value. The dataset was assessed using the Standard STRUCTURE model (a) and the LOCPRIOR model (b) that accounts for known locality data prior to the run. Colours represent each of the predefined clusters to which each sample is assigned.

Figure 3.

STRUCTURE bar plots showing the proportion of membership of samples assigned to the optimum K within the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex. Results are based on ISSR fragments scored at a 50 relative fluorescence unit (rfu) cut-off value. The dataset was assessed using the Standard STRUCTURE model (a) and the LOCPRIOR model (b) that accounts for known locality data prior to the run. Colours represent each of the predefined clusters to which each sample is assigned.

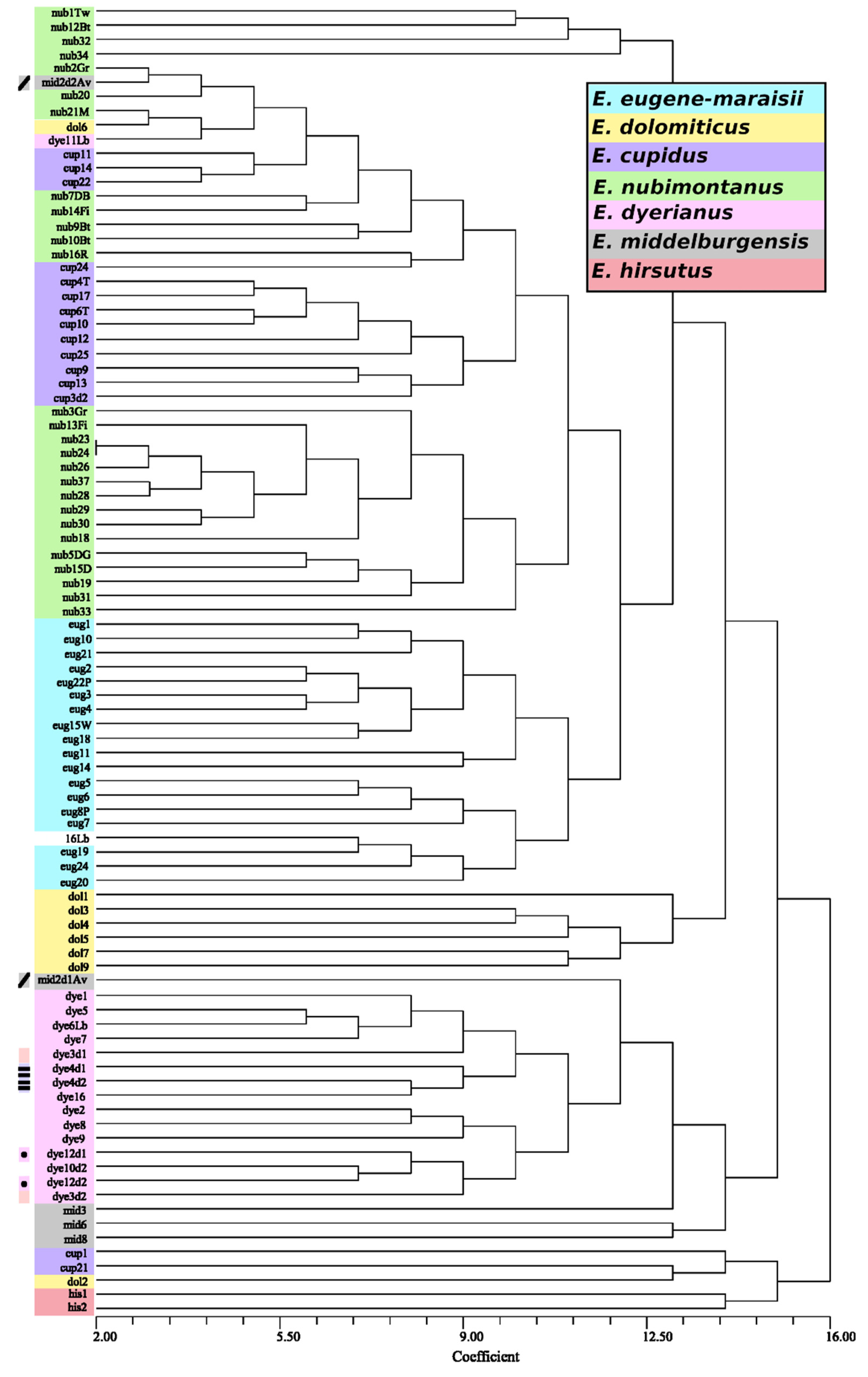

Figure 4.

Neighbor joining analysis of the

Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex based on ISSR markers with a minimum band intensity of 50 relative fluorescence units (rfu). The colour of each sample corresponds to its species and sample names are represented by the first three letters of their species epithet, corresponding to

Table S5. Sample duplicates, representing material obtained from the same plant, but extracted in a different DNA extraction batch, are indicated by the coloured rectangles. Genetic distances were computed using the DICE coefficient. Band presence and absence was used to compute genetic distances using the DICE coefficient.

Figure 4.

Neighbor joining analysis of the

Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex based on ISSR markers with a minimum band intensity of 50 relative fluorescence units (rfu). The colour of each sample corresponds to its species and sample names are represented by the first three letters of their species epithet, corresponding to

Table S5. Sample duplicates, representing material obtained from the same plant, but extracted in a different DNA extraction batch, are indicated by the coloured rectangles. Genetic distances were computed using the DICE coefficient. Band presence and absence was used to compute genetic distances using the DICE coefficient.

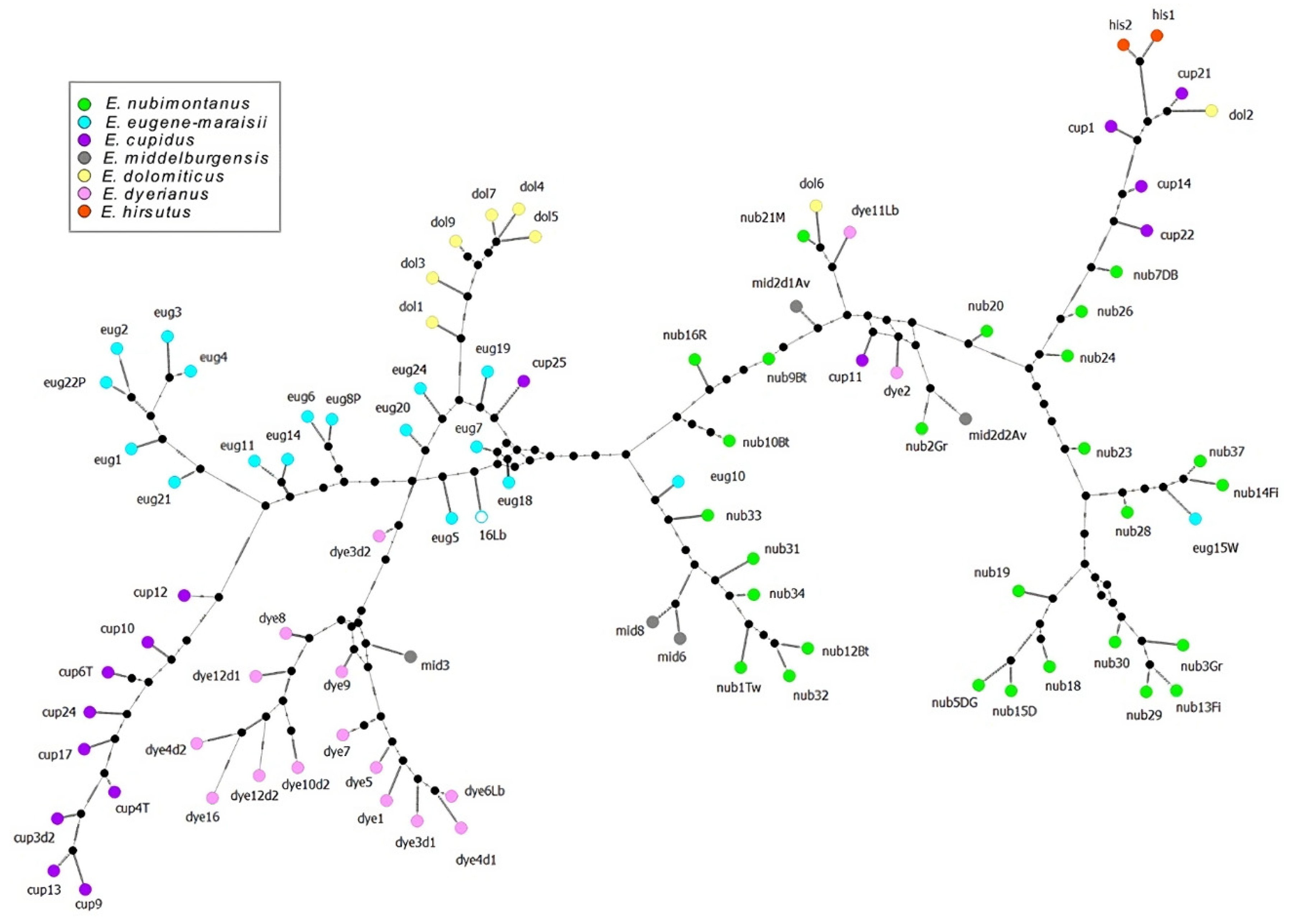

Figure 5.

Median joining network of the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex based on ISSR markers with a minimum band intensity of 50 relative fluorescent units. Colours denote the species of each sample in this study.

Figure 5.

Median joining network of the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex based on ISSR markers with a minimum band intensity of 50 relative fluorescent units. Colours denote the species of each sample in this study.

Table 1.

Top thirty countries from which authors of publications using ISSR’s emanate based on VOSViewer analysis of data from SCOPUS. Countries in bold are listed as developing nations (as from

https://www.worlddata.info/developing-countries.php). Numbers in parentheses behind country names indicate ranking according to Biodiversity Index (

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megadiverse_countries). Note that the total number of publications listed sums to a number greater than the 7852 publications extracted from SCOPUS as a consequence of multi-author papers by authors from multiple countries.

Table 1.

Top thirty countries from which authors of publications using ISSR’s emanate based on VOSViewer analysis of data from SCOPUS. Countries in bold are listed as developing nations (as from

https://www.worlddata.info/developing-countries.php). Numbers in parentheses behind country names indicate ranking according to Biodiversity Index (

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megadiverse_countries). Note that the total number of publications listed sums to a number greater than the 7852 publications extracted from SCOPUS as a consequence of multi-author papers by authors from multiple countries.

| Rank |

Country |

Number of publications |

% of total publications |

| 1 |

India (8) |

1591 |

17.4 |

| 2 |

China (4) |

1493 |

16.4 |

| 3 |

United States of America (10) |

625 |

6.8 |

| 4 |

Iran |

504 |

5.5 |

| 5 |

Brazil (1) |

447 |

4.9 |

| 6 |

Egypt |

384 |

4.2 |

| 7 |

Türkiye |

275 |

3.0 |

| 8 |

Italy |

246 |

2.7 |

| 9 |

Saudi Arabia |

244 |

2.7 |

| 10 |

Russian Federation |

225 |

2.5 |

| 11 |

Poland |

186 |

2.0 |

| 12 |

Spain |

181 |

2.0 |

| 13 |

Germany |

179 |

2.0 |

| 14 |

Japan |

164 |

1.8 |

| 15 |

Mexico (5) |

153 |

1.7 |

| 16 |

United Kingdom |

150 |

1.6 |

| 17 |

France |

140 |

1.5 |

| 18 |

Canada |

133 |

1.5 |

| 19 |

Australia (6) |

129 |

1.4 |

| 20 |

Portugal |

118 |

1.3 |

| 21 |

Malaysia (15) |

109 |

1.2 |

| 22 |

Thailand (20) |

102 |

1.1 |

| 23 |

Indonesia (2) |

94 |

1.0 |

| 24 |

South Korea |

86 |

0.9 |

| 25 |

Argentina |

83 |

0.9 |

| 26 |

Tunisia |

76 |

0.8 |

| 27 |

Greece |

64 |

0.7 |

| 28 |

Pakistan |

59 |

0.6 |

| 29 |

South Africa (19) |

54 |

0.6 |

| 30 |

Czech Republic |

52 |

0.6 |

| 21 |

Malaysia (15) |

109 |

1.2 |

| 22 |

Thailand (20) |

102 |

1.1 |

| 23 |

Indonesia (2) |

94 |

1.0 |

| 24 |

South Korea |

86 |

0.9 |

| 25 |

Argentina |

83 |

0.9 |

| 26 |

Tunisia |

76 |

0.8 |

| 27 |

Greece |

64 |

0.7 |

| 28 |

Pakistan |

59 |

0.6 |

| 29 |

South Africa (19) |

54 |

0.6 |

| 30 |

Czech Republic |

52 |

0.6 |

Table 2.

ISSR primers screened in this study. The primers are manufactured by Inqaba Biotechnical Industries

Table 2.

ISSR primers screened in this study. The primers are manufactured by Inqaba Biotechnical Industries

| ISSR Primer Name |

5’ Fluorescent marker |

Sequence |

| Manny |

6-FAM |

CACCACCACCACRC |

| 812 |

HEX |

GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAA |

| Mao |

TET |

CTCCTCCTCCTCRC |

| Omar |

HEX |

GAGGAGGAGGAGRC |

| 864 |

6-FAM |

ATGATGATGATGATGATG |

| 856 |

TET |

ACACACACACACACACYA |

Table 3.

Comparison of twelve datasets for different ISSR primers at three relative fluorescence unit (rfu) cut-offs. Datasets were generated using GeneMapper Software Version 5 (Applied Biosystems, USA) and based on electropherogram outputs obtained from the ABI3130 genetic analyser. Bands were scored “1” for presence if above the -rfu threshold and “0” for absence if below this threshold.

Table 3.

Comparison of twelve datasets for different ISSR primers at three relative fluorescence unit (rfu) cut-offs. Datasets were generated using GeneMapper Software Version 5 (Applied Biosystems, USA) and based on electropherogram outputs obtained from the ABI3130 genetic analyser. Bands were scored “1” for presence if above the -rfu threshold and “0” for absence if below this threshold.

| Primer |

Minimum fluorescence (rfu) |

Total number of bands obtained from all samples |

Mean bands per sample |

Private bands |

| ISSR Mao (TET) |

50 |

111 |

12 |

32 |

| ISSR Mao (TET) |

100 |

83 |

7 |

22 |

| ISSR Mao (TET) |

200 |

30 |

4 |

6 |

| ISSR 864 (6-FAM) |

50 |

459 |

44 |

68 |

| ISSR 864 (6-FAM) |

100 |

327 |

19 |

32 |

| ISSR 864 (6-FAM) |

200 |

73 |

12 |

28 |

| ISSR 856 (TET) |

50 |

93 |

11 |

21 |

| ISSR 856 (TET) |

100 |

29 |

3 |

5 |

| ISSR 856 (TET) |

200 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

| Combined |

50 |

663 |

22 |

121 |

| Combined |

100 |

439 |

10 |

59 |

| Combined |

200 |

113 |

5 |

35 |

Table 4.

An analysis of DNA purity as determined by Nanodrop as relating to the success of DNA extractions and subsequent PCR amplification success. Percentage successful amplification was calculated based on the number of PCR amplifications which produced clear, distinguishable bands as a percentage of the total PCR amplifications performed with the three selected primers. DNA extracts of samples which did not form bands on agarose gel for any of the primers and were subsequently omitted from the study are shown for the first and second batches of automated DNA extraction.

Table 4.

An analysis of DNA purity as determined by Nanodrop as relating to the success of DNA extractions and subsequent PCR amplification success. Percentage successful amplification was calculated based on the number of PCR amplifications which produced clear, distinguishable bands as a percentage of the total PCR amplifications performed with the three selected primers. DNA extracts of samples which did not form bands on agarose gel for any of the primers and were subsequently omitted from the study are shown for the first and second batches of automated DNA extraction.

| Species |

Mean DNA concentration (ng/μl) |

Mean 260/280 |

Mean 260/230 |

Number of samples |

Percentage successful amplification |

| E. eugene-maraisii |

302.6 |

1.64 |

0.5 |

35 |

55.5% |

| E. nubimontanus |

373.1 |

1.34 |

0.58 |

48 |

54.1% |

| E. hirsutus |

328.2 |

1.65 |

0.53 |

2 |

100% |

| E. dyerianus |

286.5 |

1.4 |

0.6 |

27 |

56% |

| E. middelburgensis |

294.4 |

1.45 |

0.55 |

23 |

24.6% |

| E. cupidus |

491.8 |

1.3 |

0.62 |

46 |

36.2% |

| E. dolomiticus |

344.3 |

1.6 |

0.49 |

13 |

60% |

| Omitted samples Batch 1 |

350.3 |

1.61 |

0.51 |

46 |

0% |

| Omitted samples Batch 2 |

610.4 |

1.20 |

0.62 |

23 |

0% |

Table 5.

Statistics used in calculating Tajima’s D statistic for genetic isolation between species of the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex computed in PopART software, based on ISSR fragments.

Table 5.

Statistics used in calculating Tajima’s D statistic for genetic isolation between species of the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex computed in PopART software, based on ISSR fragments.

| |

-rfu cut-off dataset |

| |

50 |

100 |

200 |

| Nucleotide diversity (π) |

0.111362 |

0.06931 |

0.154567 |

| Segregating sites |

474 |

207 |

105 |

| Tajima's D statistic |

-0.70597 |

-0.84998 |

-0.50775 |

| Significance (p) |

0.743371 |

0.79021 |

0.673339 |

Table 6.

AMOVA of taxa in the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex computed in PopART Software, based on ISSR fragments. Species were grouped into pairs, namely E. cupidus and E. dolomiticus; E. dyerianus and E. eugene-maraisii; E. middelburgensis and E. nubimontanus, while E. hirsutus was assigned its own group.

Table 6.

AMOVA of taxa in the Encephalartos eugene-maraisii complex computed in PopART Software, based on ISSR fragments. Species were grouped into pairs, namely E. cupidus and E. dolomiticus; E. dyerianus and E. eugene-maraisii; E. middelburgensis and E. nubimontanus, while E. hirsutus was assigned its own group.

| |

-rfu cut-off dataset |

| |

50 |

100 |

200 |

| Variation among groups (%) |

-1.89289 |

-7.46642 |

-2.86349 |

| Fixation index ΦCT

|

-0.01893 |

-0.07466 |

-0.02863 |

| Significance (1000 permutations): |

0.378 |

0.42957 |

0.529 |

| Variation among species within groups (%) |

37.31296 |

46.16488 |

34.46871 |

| Fixation index ΦSC

|

0.3662 |

0.42957 |

0.33509 |

| Significance (1000 permutations): |

<0.001 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

| Variation among species among groups (%) |

64.57993 |

61.30154 |

68.39479 |

| Fixation index ΦST

|

0.3542 |

0.38698 |

0.31605 |

| Significance (1000 permutations): |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

Table 7.

Results from the Evanno method generated from STRUCTURE Harvester used to determine the optimal value of K. Ten independent runs of each model were run in STRUCTURE software using a 10 000 iteration burn in and 100 000 MCMC iterations. The table shows entries of the runs with the top three delta K values for each STRUCTURE model used. It is assumed that runs with the largest Delta K indicate the optimal K value.

Table 7.

Results from the Evanno method generated from STRUCTURE Harvester used to determine the optimal value of K. Ten independent runs of each model were run in STRUCTURE software using a 10 000 iteration burn in and 100 000 MCMC iterations. The table shows entries of the runs with the top three delta K values for each STRUCTURE model used. It is assumed that runs with the largest Delta K indicate the optimal K value.

| STRUCTURE model |

K |

Reps |

Mean LnP(K) |

Stdev LnP(K) |

Ln'(K) |

|Ln''(K)| |

Delta K |

| 50rfu dataset |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Standard |

3 |

10 |

-10285.48 |

2.26019 |

673.2 |

300.53 |

132.96688 |

| |

4 |

10 |

-9912.81 |

68.14371 |

372.67 |

4205.43 |

61.71413 |

| |

2 |

10 |

-10958.68 |

24.08724 |

762.99 |

89.79 |

3.7277 |

| LOCPRIOR |

4 |

10 |

-9890.92 |

11.29796 |

394.28 |

2663.47 |

235.74778 |

| |

3 |

10 |

-10285.2 |

5.27952 |

673.84 |

279.56 |

52.95178 |

| |

2 |

10 |

-10959.04 |

55.6032 |

762.26 |

88.42 |

1.5902 |

| 100rfu dataset |

|

|

|

| Standard |

2 |

10 |

-4331.6 |

0.80139 |

481.21 |

176.68 |

220.46758 |

| |

3 |

10 |

-4027.07 |

2.03909 |

304.53 |

323.73 |

158.76198 |

| |

4 |

10 |

-4046.27 |

408.31331 |

-19.2 |

387.34 |

0.94863 |

| LOCPRIOR |

3 |

10 |

-4051.01 |

6.14138 |

318.47 |

1845.36 |

300.47967 |

| |

2 |

10 |

-4369.48 |

17.8674 |

443.28 |

124.81 |

6.98535 |

| |

7 |

10 |

-4022.16 |

418.53457 |

976.32 |

1844.54 |

4.40714 |

| 200rfu dataset |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Standard |

2 |

10 |

-2499.8 |

2.28619 |

214.9 |

118.48 |

51.8242 |

| |

5 |

10 |

-2209.93 |

11.79426 |

144.62 |

115.61 |

9.80223 |

| |

6 |

10 |

-2180.92 |

18.74145 |

29.01 |

96.91 |

5.17089 |

| LOCPRIOR |

2 |

10 |

-2487.96 |

1.1462 |

226.58 |

125 |

109.05587 |

| |

3 |

10 |

-2386.38 |

2.85299 |

101.58 |

44.26 |

15.51355 |

| |

4 |

10 |

-2240.54 |

23.62359 |

145.84 |

191.7 |

8.11477 |