1. Introduction

Posterior tooth loss, a prevalent oral condition in clinical practice, can lead to significant functional impairments and esthetic issues, thereby diminishing the patients' quality of life [

1]. Multiple relevant studies have indicated that posterior tooth loss is among the primary causes of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) [[2[

4]. TMD encompasses a set of musculoskeletal and/or neuromuscular dysfunctions that affect the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masticatory muscles, and related tissues [

5]. Related investigations have demonstrated that TMD is a common oral health concern, with an incidence rate ranging from 28% to 50% [

6,

7].

Dental implant restoration has emerged as the preferred option for replacing missing posterior teeth. This is attributed to its distinct advantages, such as the absence of the need for grinding natural teeth, stable usage, robust performance, high efficiency, aesthetic appeal, and convenience [[8[

10]. Given the high prevalence of TMD in the general population and the growing trend of oral rehabilitation using dental implants, the ongoing debate regarding whether dental implant therapy exacerbates or alleviates TMD has become particularly timely.

Current studies have shown that TMD is related to the operation of prolonged mouth opening and the stability of implant prosthesis [

11]. Several studies have highlighted that one of the predominant causes of TMD in patients with posterior tooth loss undergoing implant restoration is the improper construction of maxilla-mandibular relationships. This encompassed incorrect centric relation, improper vertical dimension, and occlusal instability [

5,

12]. Some cases also reported the occurrence of TMJ related pain after the implant restoration in edentulous patients [

13].

Nevertheless, a contrasting perspective has been put forward by some scholars. They maintain that implant restoration can confer beneficial effects on augmenting the physiological functions of the TMJs. Some studies indicated that dental implant restoration has the capability to restore the normal occlusal vertical distance and to enhance the condyle position in the articular fossa, consequently diminishing the likelihood of TMD occurrence [

14,

15]. It has additionally been observed that implant repair can play a part in the rehabilitation of normal masticatory muscle function, the enhancement of the stability of the TMJ, and the exertion of a favorable influence on facilitating the normal physiological function of the TMJ [

16,

17]. Long-term clinical follow-up studies have gone a step further, uncovering that the incidence of TMD, such as joint pain, snapping, and restricted opening, is markedly reduced in patients following implant restoration [

1][

20].

The existing research regarding the impact of implant restoration on TMJ functions predominantly comprised clinical observations and imaging investigations. TMJ has been demonstrated to be a weight-bearing joint, and its physiological function is closely associated with its stress condition [

21,

22]. Either excessive or insufficient stress can precipitate degenerative remodeling of the TMJ [

23,

24]. Consequently, this study aims to explore the influence of implant restoration on the biomechanics within the TMJs, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for the treatment of implant restoration in patients with posterior tooth loss.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. It received approval from the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Three Gorges Medical College (approval number: SYYZ-H-2302-0001). Prior to the commencement of the study, each subject was provided with comprehensive information about the study procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Subsequently, all the subjects signed an informed-consent form, which explicitly consented to their participation in the examinations and the use of all relevant data generated during the course of this study.

2.1. Patients and Imaging Data Acquisition

A total of 30 volunteers, all of whom were 18 years old or above, were recruited at the Affiliated Stomatology Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. An oral surgeon identified all these subjects. Among them, 20 individuals (comprising 9 males and 11 females, with an average age of 48.05±5.86 years) who had posterior tooth loss were designated as the preoperative group (abbreviated as the Pre group). The subjects in this group were those who had not yet undergone implant restoration. Those who had received implant restoration were categorized as the postoperative group (abbreviated as the Post group). Additionally, 10 healthy volunteers (including 5 males and 5 females, with an average age of 42.46±4.89 years) with normal dentition were designated as the Control group.

For the study, the patients with posterior tooth loss had the following inclusion criteria: (1) posterior tooth loss with no orthodontic treatment until the experiment, (2) undergoing implant restoration with at least 12-month follow-up, (3) no craniomaxillofacial or nervous system diseases (congenital or acquired), and (4) no history of mental illness or psychiatric drug use. They were excluded if under 18 years of age or diagnosed with jaw osteonecrosis. Regarding healthy volunteers with normal dentition, the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) physical and mental health, no growth-related diseases, (2) facial and TMJ symmetry with no orthodontic or surgical history, and (3) no TMD or other TMJ diseases. They were excluded if under 18 years of age or had a history of maxillofacial orthodontic or surgical treatment.

All the subjects were scanned using a CBCT machine (KaVo 3D eXam, Germany) following a standardized protocol to acquire head views. The scanning parameters were set as follows: a 16×11 cm field of view (FOV), 120 kVp, 5 mA, a voxel size of 0.4 mm, and a scanning speed of 360˚/sec for 4 seconds. Patients with posterior tooth loss underwent CBCT scans both before and six months after implant restoration. The cross-sectional images had a resolution of 400 pixels and a pixel size of 0.4 mm. Each CBCT scan generated 290 to 340 images with a slice thickness of 0.4 mm. Subsequently, the CBCT data were converted into the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format.

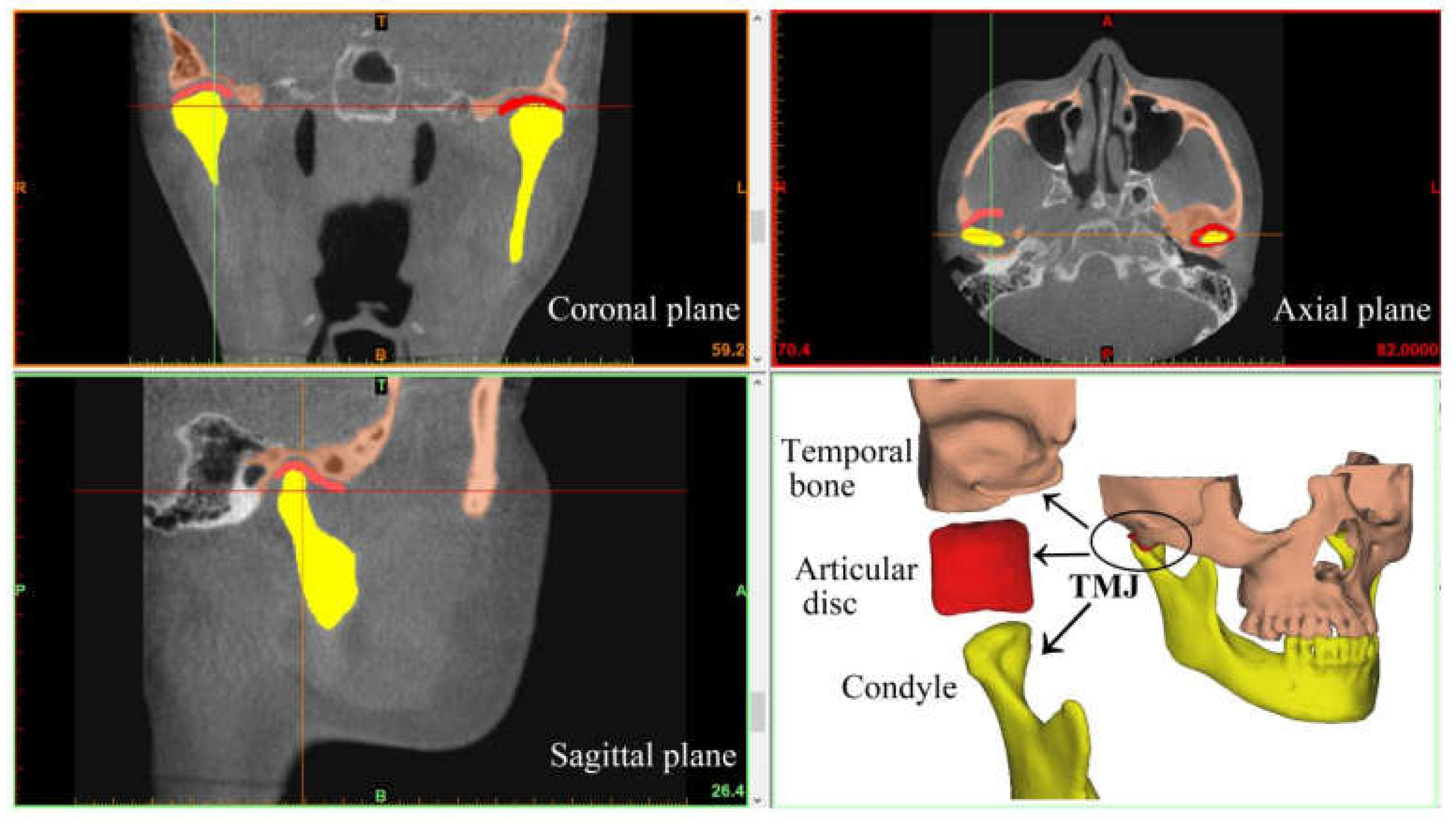

Based on grayscale values, Three-dimensional (3D) models of the subjects' maxilla, mandible and teeth were reconstructed using Mimics (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) (

Figure 1). The discs were created according to MRI images (GE medical-system, SIGNA HDe) and anatomical features. Thus, 3D models of various subjects were successfully obtained (

Figure 1,

Figure 2).

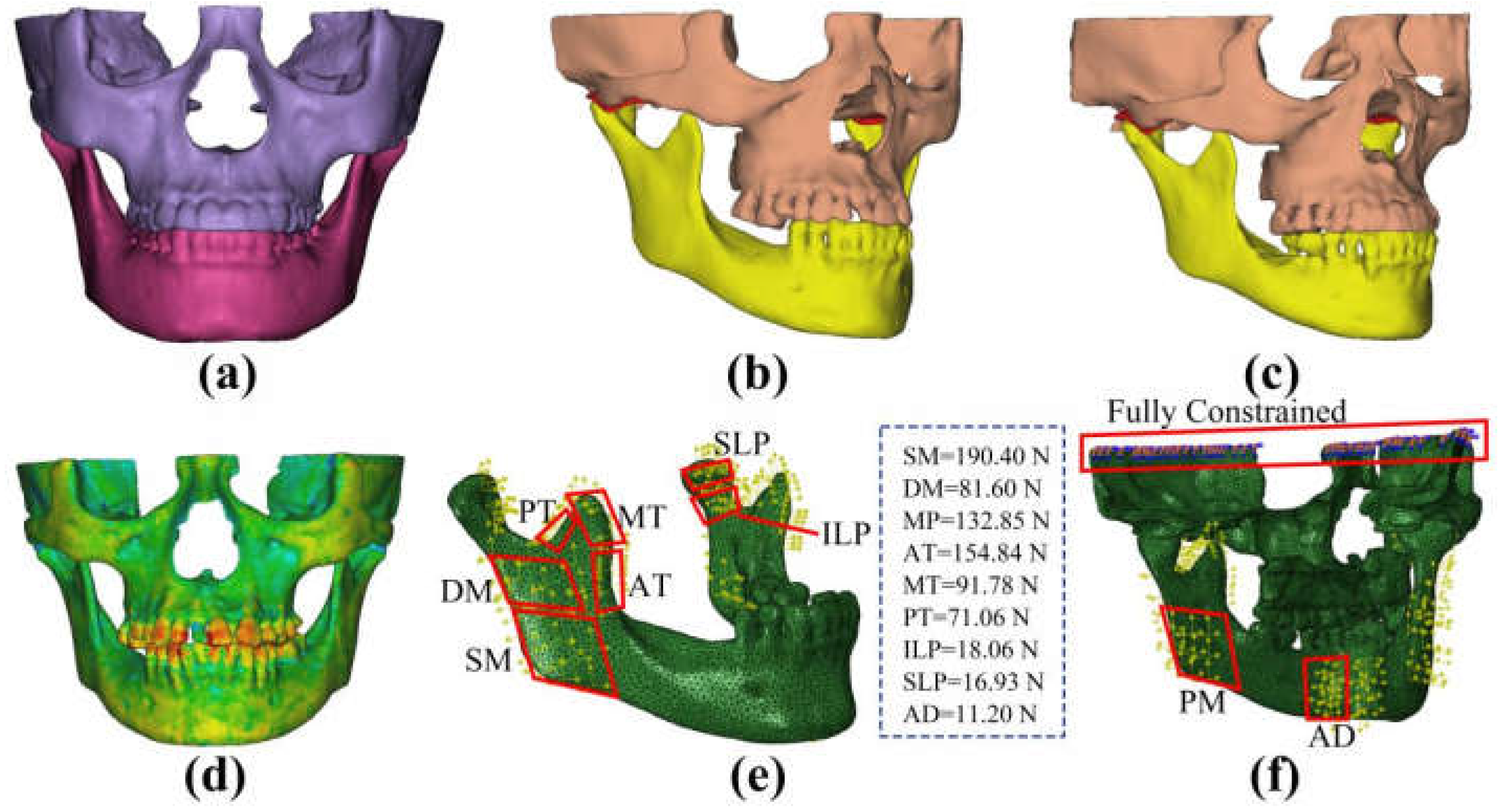

2.2. Finite Element Model

In this study, ABAQUS 6.13 software (Dassault, SIMULIA, USA) was adopted to conduct finite element analysis and calculations. Referring to the empirical formula between the material properties of bone and the grayscale value (Equation (1) and (2)), the density and elastic modulus were assigned to the maxilla and mandible. This was done to simulate the the heterogeneous material properties of bone tissue [

25,

26] (

Figure 2(d)). The Poisson’s ratio of the maxilla and mandible was assigned as 0.3 [

22,

27]. The disc was considered as a Mooney-Rivlin hyperelastic material, with parameters C1 = 9 × 105 Pa and C2 = 9 × 102 Pa. Previous studies have demonstrated that this material is well-suited for finite element analysis of the TMJ [

28,

29,

30,

31]. The strain-energy function of this material was defined as follows (Equation (3)). Furthermore, the articular cartilages with a thickness of 0.2 mm were established on the surfaces of the condyle and the articular eminence, with elastic modulus of 0.79 MPa and Poisson's ratio of 0.49 [

22].

Where GV is the gray-scale value, E is elastic modulus, C1 and C2 are material constants, and I1 and I2 are the first and second invariants of the left Cauchy-Green deformation tensor B.

To enhance both accuracy and efficiency, the modified quadratic tetrahedron element (C3D10M) was employed for the TMJ regions, while the 4-node linear tetrahedron element (C3D4) was utilized for the remaining regions of the models. The model consisted of approximately 190,000 elements and 80,000 nodes, respectively (

Figure 2(f)).

A surface-to-surface contact approach was adopted to simulate the interaction between contact surfaces. Moreover, a hard-contact condition was set with a frictional coefficient of 0.001 [

22]. Non-linear cable elements were used to model four disc attachments: the anterior temporal attachment, the anterior mandibular attachment, and the upper and lower bands of the bilaminar zone [

32]. The numbers of these elements for each attachment were 4, 4, 6, and 5 respectively.

2.3. Load Conditions

Identical loading conditions were imposed on all the models. The temporomandibular, sphenomandibular, and stylomandibular ligaments were modeled as nonlinear axial connectors [

33]. Nine primary muscle forces were taken into account, with the magnitudes and directions of the muscle forces during centric occlusion determined based on prior research (

Table 1) [

34]. The top surface of the maxilla was fully constrained (

Figure 2(f)).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 27.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). To compare the differences in biomechanical parameters between the Pre and Control groups, as well as between the Post and Control groups, either the independent sample t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was employed. The Mann-Whitney U test was utilized when the data did not follow a normal distribution and chi-square test was required. Conversely, the independent sample t-test was selected.

For comparing the differences in biomechanical parameters between the Pre and Post groups, the paired samples t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Additionally, this pair of tests was also applied to compare the differences in biomechanical parameters between the healthy side and the missing tooth side/implant restoration side of the Pre and Post groups. Statistical significance was achieved when P<0.05.

3. Results

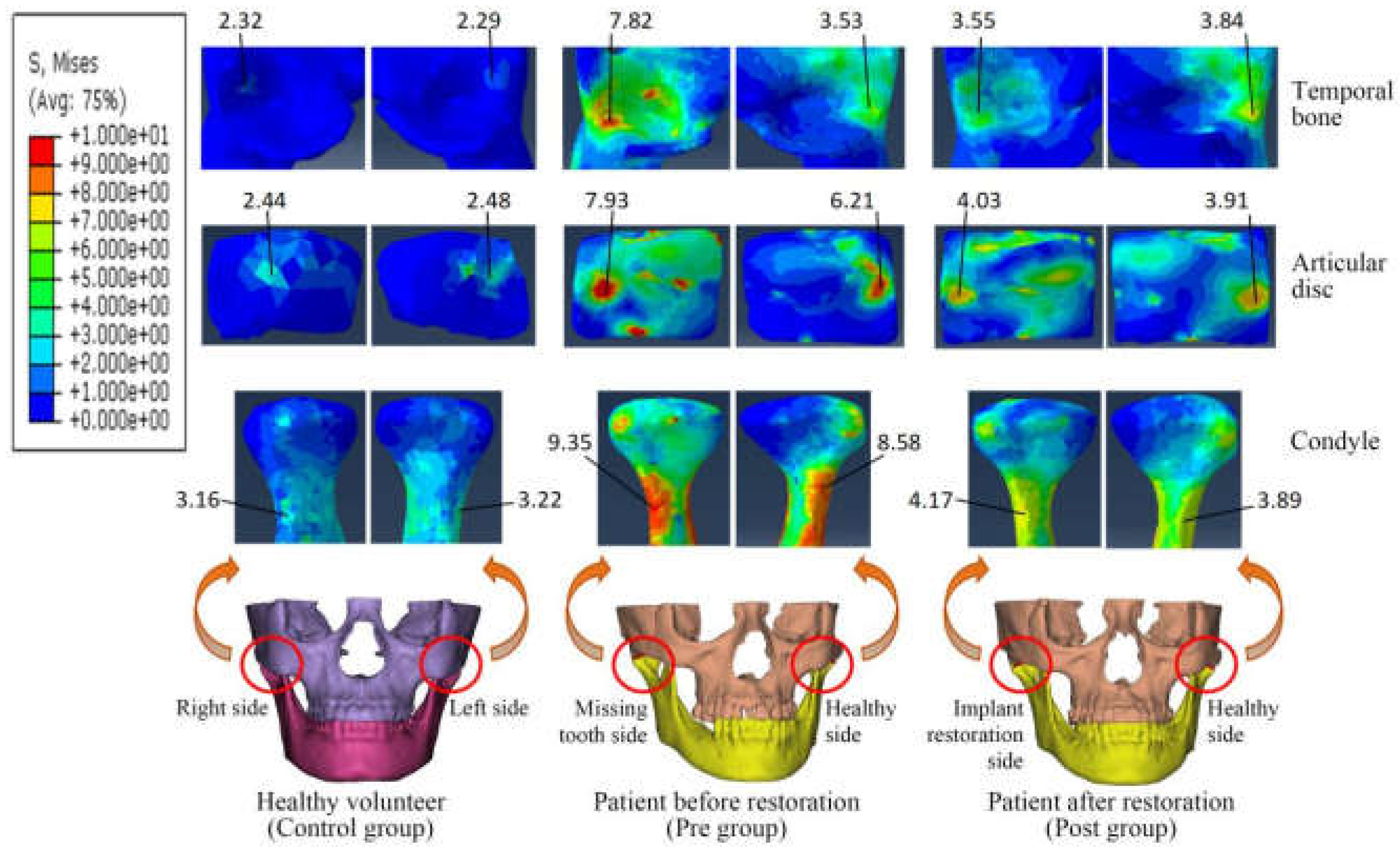

The temporomandibular joint functions as a weight-bearing joint, with its load-bearing characteristics varying under different oral conditions, including healthy dentition, missing posterior teeth, and implant restoration following tooth loss. The von Mises stress serves as an indicator of the overall stress state within the TMJ. This study revealed that the patients with posterior tooth loss (Pre group) commonly exhibited stress concentrations in the articular disc, condyle and temporal bone, with an asymmetrical stress distribution between the left and right TMJs (

Figure 3). However, after implant restoration (Post group), the stresses on the patients' TMJs became relatively uniform and basically returned to the normal level, and the stress distributions on both sides were symmetrical (

Figure 3).

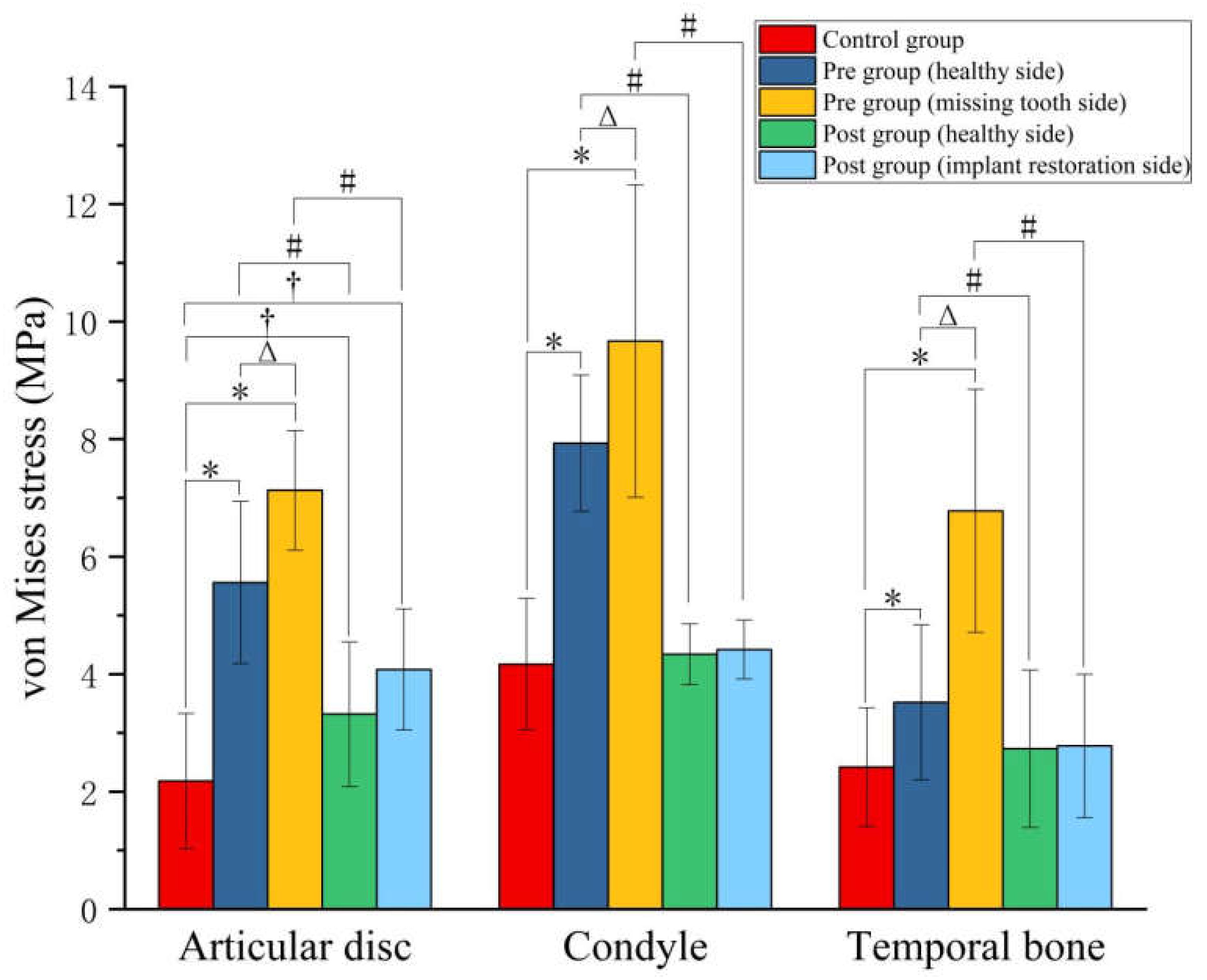

By comparing the von Mises stress differences among patients with posterior tooth loss before restoration (Pre group), after restoration (Post group), and healthy individuals (Control group), it was found that the stress magnitudes in the articular disc, condyle, and temporal bone on the missing tooth side of the Pre group were significantly greater than those on the healthy side (P < 0.05). Specifically, the differences between the two sides were 28.24%, 21.94%, and 92.61% for the articular disc, condyle, and temporal bone, respectively (

Figure 4). After implant restoration, the von Mises stress magnitudes of each TMJ structure in the Post group were comparable between the implant restoration side and healthy side, with no statistically significant differences. Furthermore, the stress magnitudes in the articular disc, condyle and temporal bone of the Pre group were also significantly greater than those of the Control group (P < 0.05), being 3.27 times, 2.32 times and 2.80 times higher, respectively. Following implant restoration, the stress magnitudes of the condyle and temporal bone in the Post group were reduced to the normal range. Although the von Mises stress magnitudes of the articular disc decreased from 3.27 times to 1.87 times the normal value, it remained significantly higher compared to the Control group (

Figure 4).

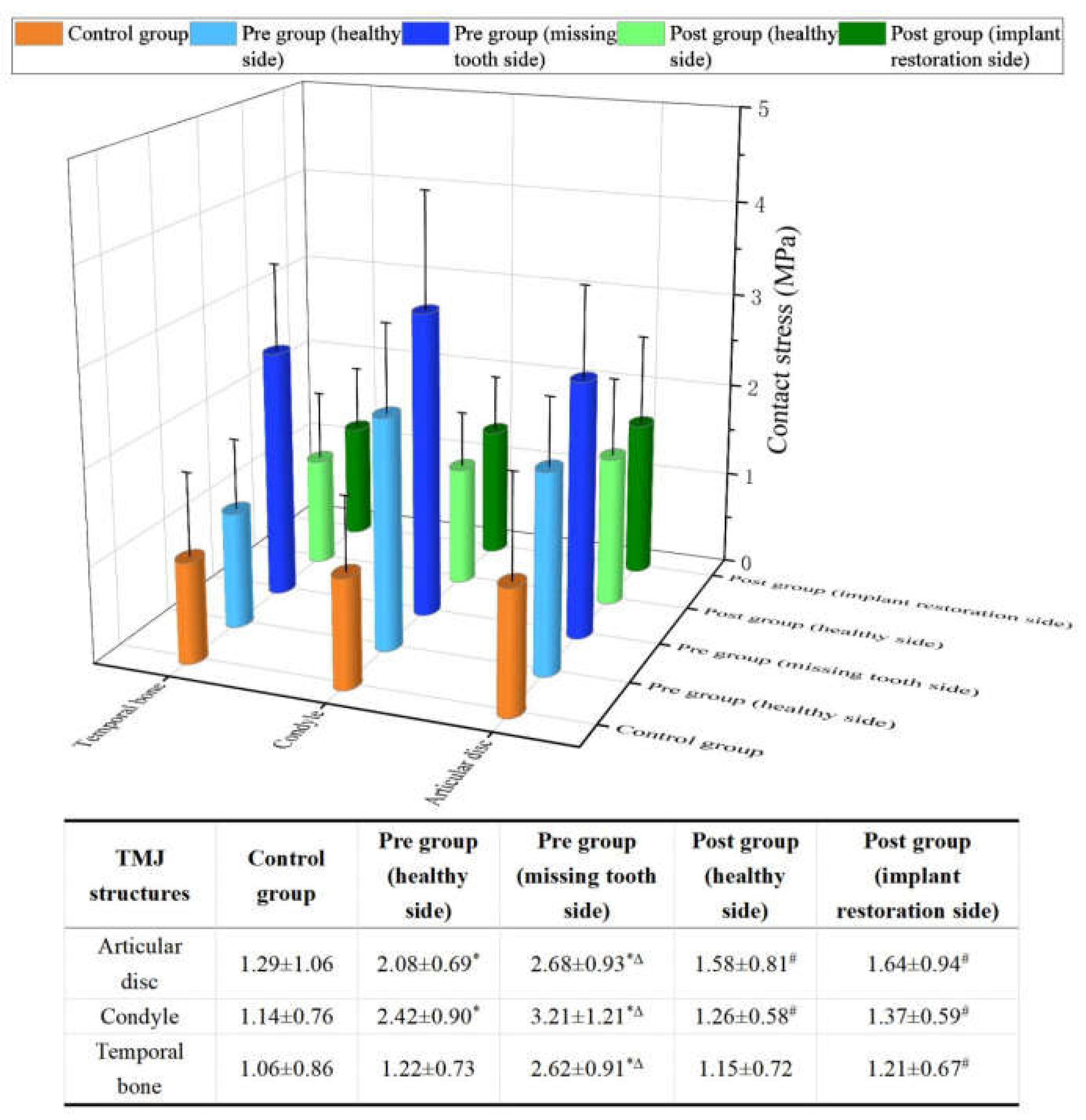

This study revealed that, prior to implant restoration, the patients with posterior tooth loss (Pre group) exhibited significantly higher contact stress in the articular disc, condyle and temporal bone compared to the Control group (P < 0.05), particularly on the side of the missing tooth (

Figure 5). Following implant restoration, there were marked reductions in contact stresses of articular disc, condyle and temporal bone, decreasing by 38.81%, 57.32%, and 53.82% respectively, compared to pre-restoration levels (

Figure 5). Additionally, after implant restoration, the contact stress on the both TMJs (Post group) became nearly equal and exhibited no significant statistical difference from the Control group (

Figure 5).

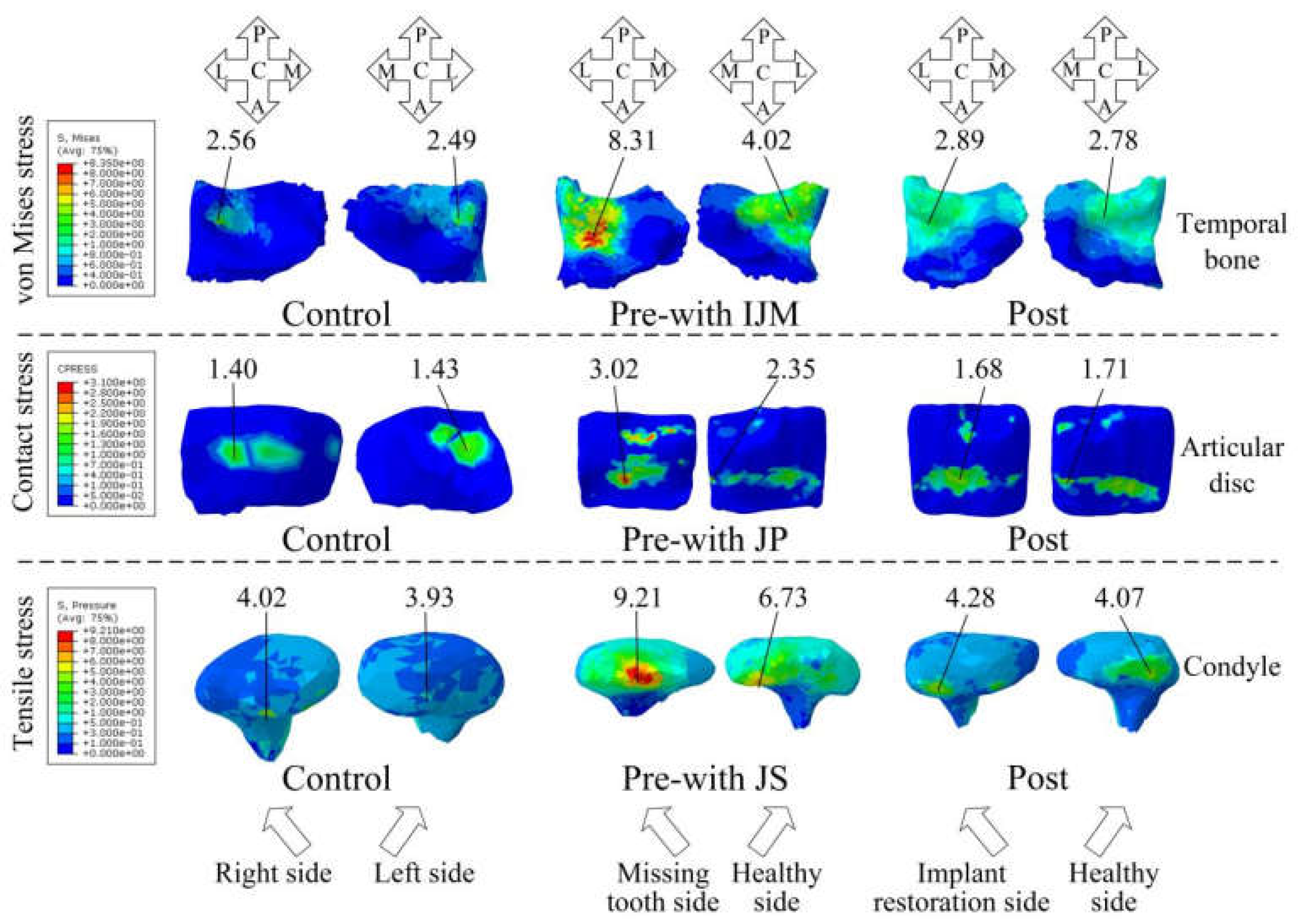

Prior to implant restoration, a majority of patients with posterior tooth loss exhibited TMD symptoms. Specifically, 15 cases presented with inconsistent joint mobility, 12 cases reported joint pain, and 13 cases experienced joint sounds. Significant differences in the magnitudes and distributions of stress were observed between these patients and the Control group. This study revealed that for the patients with inconsistent joint mobility (Pre-with IJM), von Mises stress concentration in the temporal bone was predominantly located in the glenoid fossa, with stress magnitudes notably exceeding normal levels (as seen in the Control group) (

Figure 6). After implant restoration, the TMD symptoms in the patients were greatly improved, and only 3 patients still had slight symptoms of joint pain. Meanwhile, the magnitudes of von Mises stress in the temporal bone of these patients were largely normalized, and their stress distribution was aligned with that of the Control group, with a concentration on the posterior slope of the articular tubercle (

Figure 6).

For the patients experiencing joint pain prior to implant restoration (Pre-with JP), high contact stress regions on the articular disc were primarily found in the anterior and posterior bands. Following implant restoration, the contact stress on the articular disc was significantly reduced to normal ranges (as seen in the Control group); however, the elevated stress regions remained concentrated in the anterior band of the articular disc. This stress distribution contrasts with that observed in the Control group, where high-stress regions were primarily located in the intermediate zone of the articular disc (

Figure 6).

This study revealed that the patients with joint sounds (Pre-with JS) exhibited significantly elevated condylar tensile stress levels compared to normal values (as seen in the Control group), predominantly localized in the transverse ridge of the condyle. Following implant restoration, the condylar tensile stress in these patients was markedly reduced and returned to nearly normal levels. The stress distribution pattern also aligned with that of the Control group, with a concentration on the anterior slope of the condyle (

Figure 6).

For the patients with posterior tooth loss without TMD symptoms, the stress magnitudes in the TMJ structures were lower than those with TMD symptoms prior to implant restoration. However, these posttherapeutic magnitudes were still significantly higher than those of the Control group. Additionally, it also showed that the stress magnitude on the missing tooth side was greater (

Figure 6,

Table 2). Following implant restoration, the stress levels in the TMJ structures were significantly reduced compared to pre-restoration levels, without statistically significant difference observed relative to the Control group (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study is to investigate the impact of dental implant restoration on the biomechanical parameters (von Mises stress, contact stress, and tensile stress) of the TMJ in the patients with posterior tooth loss. Specifically, this research explores the changes of these biomechanical parameters in the patients with and without TMD symptoms before and after implant restoration. The findings are intended to provide a theoretical foundation for optimizing clinical applications of implant restoration in patients with posterior tooth loss. The von Mises stress was selected to represent the overall stress distribution within the TMJ. Tensile stress was utilized to assess tensile damage to bone and soft tissues, while contact stress was employed to analyze compression between the articular disc and condyle, as well as between the articular disc and temporal bone.

In our previous studies [

35,

36], the accuracy of the simulation was verified through the experiments using five 3D printed models. The finite element and experimental models shared the same geometries, material properties, load conditions, and boundary conditions. The maximum differences between the measured strains (from the 3D printed models) and the calculated strains (from the finite element models) were less than 5% [

37,

38]. Furthermore, in this study, the maximum contact stress of the articular discs of healthy volunteers was found to be 1.29 MPa, consistent with the similar research findings of Zhu et al. [

31]. Additionally, this study found that the maximum von Mises stress of the condyles of healthy volunteers was 4.17 MPa, and related similar studies have shown that the maximum von Mises stress of the condyles of healthy volunteers was 4.21 MPa [

39]. Therefore, the simulation method was reasonable in this study.

As a pair of weight-bearing joints, the bilateral TMJs benefit from appropriate stress stimulation, which plays a crucial role in maintaining the normal dynamic remodeling process and physiological functions. This research uncovered that the loss of posterior teeth would trigger a significant elevation in the stress of the TMJ, with the missing tooth side being particularly affected. Specifically, the maximum von Mises stresses of the temporal bone, articular disc and condyle on the missing tooth side were 3.27, 2.32, and 2.80 times greater than those recorded in the normal Control group, respectively (

Figure 3,

Figure 4). According to Wolff's law [

23], excessive stress prompts an enhancement in the activity of osteoblasts, and stimulates bone proliferation. This, in turn, leads to the expansion of the bearing area and facilitates the establishment of a new physiological equilibrium. By comparing the von Mises stresses of the temporal bones in the patients exhibiting inconsistent joint mobility symptoms and those without TMD symptoms, it was revealed that the patients with TMD symptoms displayed greater stress deviations on the both TMJs. These findings further corroborated the fact that inconsistent stress distribution across the TMJs would result in disparate remodeling of the joint surface. Specifically, the side subjected to greater stress exhibits larger bearing area after joint remodeling, which results in structural asymmetry and inconsistent joint mobility between the both TMJs. This conclusion is supported by clinical follow-up records, which indicated that 15 out of 20 patients exhibited the symptoms associated with inconsistent joint mobility prior to implant restoration.

Following implant restoration, a remarkable reduction was observed in the von Mises stresses of all TMJ structures, with magnitudes largely returning to the normal range. Concurrently, the stress distribution on the both TMJs reverted from an asymmetric to a symmetric state. Clinical follow-up records also verified that after the implant procedure, the symptoms of inconsistent joint mobility on the both TMJs in the patients had vanished completely. These results indicated that restoring normal stress levels in the TMJ can re-establish physiological equilibrium, which suggests a close relationship between stress distribution and TMJ function.

Furthermore, combining observations of TMJ stress changes before and after implant restoration with clinical manifestations of TMD symptoms, we found that when TMJ stress distributions were asymmetrical and the stress magnitudes were significantly higher than normal (as seen in the Control group), progressive asymmetric remodeling of TMJ bone tissue occurred. The joint surface area with higher stress increased after reconstruction, leading to bilateral TMJ asymmetry and clinical signs of inconsistent joint mobility. After implant restoration, the stress distribution of the bilateral TMJs in the patients became essentially symmetric, and the stress levels returned to the normal range. As a result, the TMJ remodeling resumed its normal physiological balance, and the bilateral TMJs became predominantly symmetric after remodeling. Consequently, TMD symptoms such as inconsistent joint mobility that were present prior to restoration disappeared. The outcomes of this study demonstrated that implant restoration could effectively diminish the stress level of the TMJs in patients with posterior tooth loss and optimize the symmetric stress distributions of the bilateral TMJs. This enabled the TMJ remodeling to return to its normal physiological equilibrium and thereby achieved the clinical objective of eliminating inconsistent joint motion.

As is commonly known, contact stress indicates the degree of extrusion between two objects. This study found that posterior tooth loss caused the contact stresses of bilateral TMJs to be significantly higher than those of the Control group, particularly on the side with the missing tooth. There, the contact stresses of the articular disc, condyle and temporal bone were 2.08, 2.82, and 2.47 times those of the Control group, respectively. After implant restoration, the contact stresses on the both TMJs were significantly reduced, with those of the articular disc, condyle and temporal bone being 1.27, 1.20, and 1.14 times those of the Control group, slightly above normal range. The clinical follow-up of the 20 patients with posterior tooth loss showed that 12 patients exhibited joint pain before restoration. Following implant restoration, only 3 patients still have slight joint pain, while the rest have no such symptoms. These results suggested a close correlation between biomechanical parameters and clinical symptoms. Posterior tooth loss aggravated the extrusion between the condyle and the articular disc, and between the temporal bone and the articular disc, and thus increased the pressure within the TMJ and leading to joint pain. After restoration, the contact levels among the TMJ structures were greatly relieved, basically returning to normal physiological state, and thus preoperative joint pain symptoms were alleviated or gone.

Does the presence or absence of TMD symptoms among the patients with posterior tooth loss exert an impact on the stresses within the TMJs? This study has demonstrated that such an impact undoubtedly exists. This study found that prior to implant restoration, the magnitudes of von Mises stress, contact stress, and tensile stress were the highest in the patients with posterior tooth loss accompanied by TMD symptoms (such as inconsistent joint mobility, joint pain, and joint sounds), followed by those in the patients with posterior tooth loss but without TMD symptoms, and were the lowest in the Control group (

Figure 6,

Table 2). Furthermore, in the patients with posterior tooth loss, regardless of whether they had TMD or not, the stresses on the side of the missing teeth were relatively higher. These results suggested that both posterior tooth loss and TMD can lead to a significant increase in the stress on the TMJs.

After implant restoration, the stresses in the patients with posterior tooth loss, whether they had TMD or not, decreased significantly and basically reverted to the normal range (

Figure 6,

Table 2). Additionally, the clinical follow-up records of this study revealed that among the 20 patients with posterior tooth loss recruited herein, the symptom of inconsistent joint mobility completely vanished in the 15 patients of the “Pre-with IJM” group. Similarly, the symptom of joint sounds completely disappeared in the 13 patients of the “Pre-with JS” group. This might be associated with the fact that after implant restoration, the stresses of the patients in the “Pre-with IJM” group and the “Pre-with JS” group dropped to 1.08 times and 1.01 times those of the Control group, respectively, from 3.25 times and 2.29 times those of the Control group. The deviations of the stress magnitudes of the above two groups of patients from the normal range (the magnitudes in the Control group) were all within 10% after implant restoration. Moreover, among the 12 patients with joint pain in the “Pre-with JP” group, the symptom completely disappeared in 9 patients after implant restoration, while 3 patients still had a slight degree of joint pain. This might be related to the fact that the stress in the patients of the “Pre-with JP” group decreased from 2.16 times to 1.22 times those of the Control group. The stress of such patients still deviated from the normal level by 22%, so clinically, there were still 3 patients who still had slight joint pain after implant restoration. Relevant studies have also pointed out that excessive stress on the TMJ would lead to TMD symptoms [

40,

41].

The above results suggested that the stress magnitude on the TMJ was closely intertwined with TMD symptoms, and excessive stress would prompt patients to develop TMD symptoms like joint pain. Besides, this study also highlighted that implant restoration could more effectively improve the stress state of the TMJ in patients with posterior tooth loss, essentially restoring it to the normal level and alleviating or even eliminating TMD symptoms.

In the current study, all the participants were sourced exclusively from a single medical institution. Moreover, the loading conditions of the model were confined merely to static centric occlusion. These constraints are likely to impinge upon the generalizability of the research findings to a certain degree. Looking ahead, future investigations will take into account multi-center trials and integrate the parameters related to TMJ kinematics. By doing so, a more profound and all-encompassing comprehension of the dynamic mechanisms underlying the TMJ can be achieved.

5. Conclusions

Dental implant restoration can significantly improve the asymmetric stress distributions of the TMJs in patients with posterior tooth loss and remarkably reduce the excessive stress on the TMJ caused by tooth loss, thus enabling it to return to the normal range basically. Moreover, implant restoration can also alleviate or eliminate the TMD symptoms among patients with posterior tooth loss, including joint pain, inconsistent joint mobility and joint sounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and Z.L.; methodology, F.C. and G.Z.; software, F.C.; validation, C.Y., P.H., Y.P., H.T. and H.H.; formal analysis, Y.Z., F.C. and H.T.; investigation, C.Y., F.C., G.Z., P.H., Y.P., H.T. and H.H.; resources, C.Y., H.H. and Z.L.; data curation, Y.Z., C.Y., G.Z., P.H., Y.P. and H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; visualization, P.H., Y.P. and H.T.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. CSTB2023NSCQ-LMX0017), the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJZD-K202402705, KJQN202102712, KJQN202202702), the Key Project of Chongqing Key Laboratory of Development and Utilization of Genuine Medicinal Materials in Three Gorges Reservoir Area (Grant No. Sys20210003), the Natural Science Major Project of Chongqing Three Gorges Medical College (Grant No. XJ2021000702), and the Youth Top Talent Project of Chongqing Three Gorges Medical College.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chongqing Three Gorges Medical College (SYYZ-H-2302-0001).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TMJ |

Temporomandibular joint |

| TMD |

Temporomandibular disorders |

| CBCT |

Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

| FOV |

Field of view |

| DICOM |

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| 3D |

Three-dimensional |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| GV |

Gray-scale value |

| C3D10M |

Modified quadratic tetrahedron element |

| C3D4 |

4-node linear tetrahedron element |

| SM |

Superficial masseter |

| DM |

Deep masseter |

| MP |

Medial pterygoid |

| AT |

Anterior temporalis |

| MT |

Middle temporalis |

| PT |

Posterior temporalis |

| ILP |

Inferior head of lateral pterygoid |

| SLP |

Superior head of lateral pterygoid |

| AD |

Anterior digastric muscle |

References

- Asher, S.; Suominen, A.L.; Stephen, R.; Ngandu, T.; Koskinen, S.; Solomon, A. Association of Tooth Location, Occlusal Support and Chewing Ability with Cognitive Decline and Incident Dementia. J Clinic Periodontology 2025, 52, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlKhairAllah, H.A.; Mohan, M.P.; AlSagri, M.S. A CBCT Based Study Evaluating the Degenerative Changes in TMJs among Patients with Loss of Posterior Tooth Support Visiting Qassim University Dental Clinics, KSA: A Retrospective Observational Study. Saudi Dent J 2022, 34, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Saxena, D.; Srivastava, P.A.; Sharma, A.; Swarnakar, A.; Sharma, A. Prevalence and Severity of Temporomandibular Joint Disorder in Partially versus Completely Edentulous Patients: A Systematic Review. J Indian Prosthodont Soc 2023, 23, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabatabaei, S.; Paknahad, M.; Poostforoosh, M. The Effect of Tooth Loss on the Temporomandibular Joint Space: A CBCT Study. Clin Exp Dent Res 2024, 10, e845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ge, Z.; Lang, X.; Qiao, B.; Chen, J.; Ye, B.; Zhang, Y. A CBCT Study of Changes in Temporomandibular Joint Morphology with Immediate Implant Placement and Immediate Loaded Full-Arch Fixed Dental Prostheses. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minervini, G.; D’Amico, C.; Cicciù, M.; Fiorillo, L. Temporomandibular Joint Disk Displacement: Etiology, Diagnosis, Imaging, and Therapeutic Approaches. J Craniofac Surg 2023, 34, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, G.; Franco, R.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Almeida, L.E.; Ronsivalle, V.; Cicciù, M. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) in Obesity Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J of Oral Rehabilitation 2023, 50, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, F.M.; Mathey, A.A.; Stähli, A.; Salvi, G.E.; Brägger, U. Survival and Complication Rates of Tooth- and Implant-supported Restorations after an Observation Period up to 36 Years. Clinical Oral Implants Res 2024, 35, 1640–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirani, R.; Chantler, J.G.; Endres, J.; Jung, R.E.; Naenni, N.; Strauss, F.J.; Thoma, D.S. Clinical Outcomes of Single Implant Supported Crowns Utilising the Titanium Base Abutment: A 7.5-Year Prospective Cohort Study. J Dent 2024, 149, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossana, I.; Chiara, C.; Fortunato, A.; Marco, N.; Michele, C.; Berta, G.M.; Mattia, P.; Antonio, B. Horizontal Bone Augmentation with Simultaneous Implant Placement in the Aesthetic Region: A Case Report and Review of the Current Evidence. Medicina 2024, 60, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazão-Silva, M.T.; Guimarães, D.M.; Andrade, V.C.; Rodrigues, D.C.; Matsubara, V.H. Do Dental Implant Therapies Arouse Signs and Symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders? A Scoping Review. Cranio 2023, 41, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Silva, A.; Tobar-Reyes, J.; Vivanco-Coke, S.; Pastén-Castro, E.; Palomino-Montenegro, H. Centric Relation–Intercuspal Position Discrepancy and Its Relationship with Temporomandibular Disorders. A Systematic Review. Acta Odontol Scand 2017, 75, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagni, M.; Pirani, F.; D’Orto, B.; Ferrini, F.; Cappare, P. Clinical and Radiographic Follow-Up of Full-Arch Implant Prosthetic Rehabilitations: Retrospective Clinical Study at 6-Year Follow-Up. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 11143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Mi, L.; Bai, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Chen, L.; Bai, N.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Application of 3D Printed Titanium Mesh and Digital Guide Plate in the Repair of Mandibular Defects Using Double-Layer Folded Fibula Combined with Simultaneous Implantation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1350227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitani, M.; Takayama, Y.; Yokoyama, A. Significance of Mandibular Molar Replacement with a Dental Implant: A Theoretical Study with Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis. Int J Implant Dent 2018, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaya, B.; Duyan Yüksel, H.; Evlice, B.; Özcan, M.; Türer, O.U.; İşler, S.Ç.; Haytaç, M.C. Ultrasound Analysis of the Masseter and Anterior Temporalis Muscles in Edentulous Patients Rehabilitated with Full-Arch Fixed Implant-Supported Prostheses. Clin Oral Invest 2024, 28, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M.; Kamnoedboon, P.; Angst, L.; Müller, F. Oral Function in Completely Edentulous Patients Rehabilitated with Implant-supported Dental Prostheses: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implan Res 2023, 34, 196–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumbacher, H.; Strasser, T.; Knüttel, H.; Rosentritt, M. Long-Term Clinical Performance and Complications of Zirconia-Based Tooth- and Implant-Supported Fixed Prosthodontic Restorations: A Summary of Systematic Reviews. J Dent 2021, 111, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanatnama, E.; Frantz, L.; Ahlin, E.; Naoumova, J. Implant-Supported Crowns on Maxillary Laterals and Canines—a Long-Term Follow-up of Aesthetics and Function. Clin Oral Invest 2023, 27, 7545–7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Ma, C.; Chen, J. Polyetheretherketone versus Titanium CAD-CAM Framework for Implant-Supported Fixed Complete Dentures: A Retrospective Study with up to 5-Year Follow-Up. J Prosthodont Res 2022, 66, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-L.; Song, J.-L.; Xu, X.-C.; Zheng, L.-L.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Fan, Y.-B.; Liu, Z. Morphologic Analysis of the Temporomandibular Joint Between Patients With Facial Asymmetry and Asymptomatic Subjects by 2D and 3D Evaluation: A Preliminary Study. Medicine 2016, 95, e3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y. Effects of Several Temporomandibular Disorders on the Stress Distributions of Temporomandibular Joint: A Finite Element Analysis. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2016, 19, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prendergast, P.J.; Huiskes, R. The Biomechanics of Wolff’s Law: Recent Advances. I.J.M.S. 1995, 164, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-L.; Liu, Y.; Shu, J.-H.; Xu, X.-C.; Liu, Z. Morphological Study of the Changes after Sagittal Split Ramus Osteotomy in Patients with Facial Asymmetry: Measurements of 3-Dimensional Modelling. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018, 56, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopperdahl, D.L.; Morgan, E.F.; Keaveny, T.M. Quantitative Computed Tomography Estimates of the Mechanical Properties of Human Vertebral Trabecular Bone. J Orthop Res 2002, 20, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Ma, H.; Jia, L.; Fang, H.; Chong, D.Y.R.; Zheng, T.; Yao, J.; Liu, Z. Biomechanical Behaviour of Temporomandibular Joints during Opening and Closing of the Mouth: A 3D Finite Element Analysis. Numer Methods Biomed Eng 2020, 36, e3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, O.; Iriarte-Diaz, J.; Wilshin, S.; Dechow, P.C.; Taylor, A.B.; Mehari Abraha, H.; Aljunid, S.F.; Ross, C.F. In Vivo Bone Strain and Finite Element Modeling of a Rhesus Macaque Mandible during Mastication. Zoology 2017, 124, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagl, B.; Schmid-Schwap, M.; Piehslinger, E.; Kundi, M.; Stavness, I. A Dynamic Jaw Model With a Finite-Element Temporomandibular Joint. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, J.; Teng, H.; Shao, B.; Zheng, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z. Biomechanical Responses of Temporomandibular Joints during the Lateral Protrusions: A 3D Finite Element Study. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2020, 195, 105671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ding, X.; Feng, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, S.; Fan, Y. Biomechanical Study on Implantable and Interventional Medical Devices. Acta Mech. Sin. 2021, 37, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yin, D.; Liu, Y. Improved Stomatognathic Model for Highly Realistic Finite Element Analysis of Temporomandibular Joint Biomechanics. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2024, 160, 106780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Shu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y. The Biomechanical Effects of Sagittal Split Ramus Osteotomy on Temporomandibular Joint. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2018, 21, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Chong, D.Y.R.; Shao, B.; Liu, Z. A Deep Dive into the Static Force Transmission of the Human Masticatory System and Its Biomechanical Effects on the Temporomandibular Joint. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2023, 230, 107336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, B.; Li, A.; Shu, J.; Ma, H.; Dong, S.; Liu, Z. Three-Dimensional Morphological and Biomechanical Analysis of Temporomandibular Joint in Mandibular and Bi-Maxillary Osteotomies. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2022, 25, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Shu, J.; Wang, Q.; Teng, H.; Liu, Z. Effect of Sagittal Split Ramus Osteotomy on Stress Distribution of Temporomandibular Joints in Patients with Mandibular Prognathism under Symmetric Occlusions. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2020, 23, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chong, D.Y.R.; Liu, Z. Effects on Loads in Temporomandibular Joints for Patients with Mandibular Asymmetry before and after Orthognathic Surgeries under the Unilateral Molar Clenching. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 2020, 19, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Luo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z. 3D Printing Experimental Validation of the Finite Element Analysis of the Maxillofacial Model. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 694140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Chong, D.Y.R.; Shao, B.; Liu, Z. An Improved Finite Element Model of Temporomandibular Joint in Maxillofacial System: Experimental Validation. Ann Biomed Eng 2024, 52, 1908–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Lu, J.; Gao, X.; Zhou, J.; Dai, H.; Sun, M.; Xu, J. Biomechanical Effects of Joint Disc Perforation on the Temporomandibular Joint: A 3D Finite Element Study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y. Biomechanical Behavior of Temporomandibular Joint Movements Driven by Mastication Muscles. Numer Methods Biomed Eng 2024, 40, e3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Teng, H.; Shao, B.; Liu, Z. Biomechanical Study of Temporomandibular Joints of Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders under Incisal Clenching: A Finite Element Analysis. J Biomech 2024, 166, 112065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Reconstruction of maxillofacial 3D model.

Figure 1.

Reconstruction of maxillofacial 3D model.

Figure 2.

Finite element models and parameter settings for healthy volunteers and patients with posterior tooth loss. (a) Finite element model of a healthy volunteer (Control group); (b) Finite element model of the patient with posterior tooth loss before restoration (Pre group); (c) Finite element model of the patient with posterior tooth loss after implant restoration (Post group); (d) The material parameters: density and elastic modulus of the bones and teeth defined according to the Hounsfield units (Red and blue represent the maximum and minimum density and elastic modulus, respectively.); (e and f) Muscle forces and boundary constraints in finite element models (SM-superficial masseter, DM-deep masseter, MP-medial pterygoid, AT-anterior temporalis, MT-middle temporalis, PT-posterior temporalis, ILP-inferior head of lateral pterygoid, SLP-superior head of lateral pterygoid, AD-anterior digastric muscle).

Figure 2.

Finite element models and parameter settings for healthy volunteers and patients with posterior tooth loss. (a) Finite element model of a healthy volunteer (Control group); (b) Finite element model of the patient with posterior tooth loss before restoration (Pre group); (c) Finite element model of the patient with posterior tooth loss after implant restoration (Post group); (d) The material parameters: density and elastic modulus of the bones and teeth defined according to the Hounsfield units (Red and blue represent the maximum and minimum density and elastic modulus, respectively.); (e and f) Muscle forces and boundary constraints in finite element models (SM-superficial masseter, DM-deep masseter, MP-medial pterygoid, AT-anterior temporalis, MT-middle temporalis, PT-posterior temporalis, ILP-inferior head of lateral pterygoid, SLP-superior head of lateral pterygoid, AD-anterior digastric muscle).

Figure 3.

The von Mises stress distribution in temporal bone, articular disc and condyle of healthy volunteer and patients before and after implant restoration under the centric occlusion (unit: MPa).

Figure 3.

The von Mises stress distribution in temporal bone, articular disc and condyle of healthy volunteer and patients before and after implant restoration under the centric occlusion (unit: MPa).

Figure 4.

The average von Mises stress of articular disc, condyle and temporal bone in the Control, Pre and Post groups (unit: MPa). * indicated statistically signifcant diference between Control group and Pre group (healthy side/missing tooth side) (P < 0.05); Δ indicated statistically signifcant diference between healthy side and missing tooth side of Pre group (P < 0.05); † indicated statistically signifcant diference between Control group and Post group (healthy side/implant restoration side) (P < 0.05); and # indicated statistically signifcant diference between Pre group and Post group (compared with the same side) (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

The average von Mises stress of articular disc, condyle and temporal bone in the Control, Pre and Post groups (unit: MPa). * indicated statistically signifcant diference between Control group and Pre group (healthy side/missing tooth side) (P < 0.05); Δ indicated statistically signifcant diference between healthy side and missing tooth side of Pre group (P < 0.05); † indicated statistically signifcant diference between Control group and Post group (healthy side/implant restoration side) (P < 0.05); and # indicated statistically signifcant diference between Pre group and Post group (compared with the same side) (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

The average contact stress of articular disc, condyle and temporal bone in the Control, Pre and Post groups (unit: MPa). *Statistically signifcant diference between Control group and Pre group (healthy side/missing tooth side) (P < 0.05), ΔStatistically signifcant diference between healthy side and missing tooth side of Pre group (P < 0.05), and #Statistically signifcant diference between Pre group and Post group (compared with the same side) (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

The average contact stress of articular disc, condyle and temporal bone in the Control, Pre and Post groups (unit: MPa). *Statistically signifcant diference between Control group and Pre group (healthy side/missing tooth side) (P < 0.05), ΔStatistically signifcant diference between healthy side and missing tooth side of Pre group (P < 0.05), and #Statistically signifcant diference between Pre group and Post group (compared with the same side) (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

The von Mises stress, contact stress, tensile stress distributions of TMJ (unit: MPa). Control represents the healthy volunteer, Pre-with IJM represents the patients with inconsistent joint mobility before implant restoration, Pre-with JP represents the patients with joint pain before implant restoration, and Pre-with JS represents the patients with joint sounds, Post represents the corresponding patients after dental implant restoration, A represents anterior, P represents posterior, C represents central, L represents lateral and M represents medial.

Figure 6.

The von Mises stress, contact stress, tensile stress distributions of TMJ (unit: MPa). Control represents the healthy volunteer, Pre-with IJM represents the patients with inconsistent joint mobility before implant restoration, Pre-with JP represents the patients with joint pain before implant restoration, and Pre-with JS represents the patients with joint sounds, Post represents the corresponding patients after dental implant restoration, A represents anterior, P represents posterior, C represents central, L represents lateral and M represents medial.

Table 1.

The size, direction and efficiency of masticatory muscle forces under centric occlusion.

Table 1.

The size, direction and efficiency of masticatory muscle forces under centric occlusion.

| |

Maximum muscle force (N) |

Cos-x |

Cos-y |

Cos-z |

Efficiency (centric occlusion)

|

| L |

R |

L |

R |

L |

R |

| SM |

190.40 |

0.21 |

-0.21 |

-0.42 |

-0.42 |

0.88 |

0.88 |

1.00 |

| DM |

81.60 |

0.55 |

-0.55 |

0.36 |

0.36 |

0.76 |

0.76 |

1.00 |

| MP |

174.80 |

-0.49 |

0.49 |

-0.37 |

-0.37 |

0.79 |

0.79 |

0.76 |

| AT |

158.00 |

0.15 |

-0.15 |

-0.04 |

-0.04 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.98 |

| MT |

95.60 |

0.22 |

-0.22 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.84 |

0.84 |

0.96 |

| PT |

75.60 |

0.21 |

-0.21 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

0.47 |

0.47 |

0.94 |

| ILP |

66.90 |

-0.63 |

0.63 |

-0.76 |

-0.76 |

-0.17 |

-0.17 |

0.27 |

| SLP |

28.70 |

-0.76 |

0.76 |

-0.65 |

-0.65 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

0.59 |

| AD |

40.00 |

0.24 |

-0.24 |

0.94 |

0.94 |

-0.24 |

-0.24 |

0.28 |

Table 2.

The average stress (MPa) in the high stress regions of healthy volunteers (Control group) and the patients without TMD before and after implant restoration.

Table 2.

The average stress (MPa) in the high stress regions of healthy volunteers (Control group) and the patients without TMD before and after implant restoration.

| |

Control group |

Pre-without TMD group

(missing tooth side) |

Pre-without TMD group

(healthy side) |

Post group

(implant restoration side) |

Post group

(healthy side) |

| von Mises stress of temporal bone |

2.42±1.01 |

5.93±1.15* |

3.21±0.86*Δ

|

2.73±1.07#

|

2.69±1.12#

|

| Contact stress of articular disc |

1.29±1.06 |

2.29±0.54* |

1.72±0.33*Δ

|

1.59±0.75#

|

1.51±0.68 |

| Tensile stress of condyle |

3.90±0.82 |

7.92±1.57* |

5.81±0.42*Δ

|

4.15±0.42#

|

4.01±0.44#

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).