4.1. Driver Output

The driver output stage is a critical element for precisely controlling the power transistor, enabling rapid and reliable switching between conducting and non-conducting states. The main functions of the output stage include providing the necessary voltage to ensure full turn-on of the transistor and providing high source and sink currents to rapidly charge and discharge the gate capacitance in order to reduce the on and off times, resulting in low switching losses.

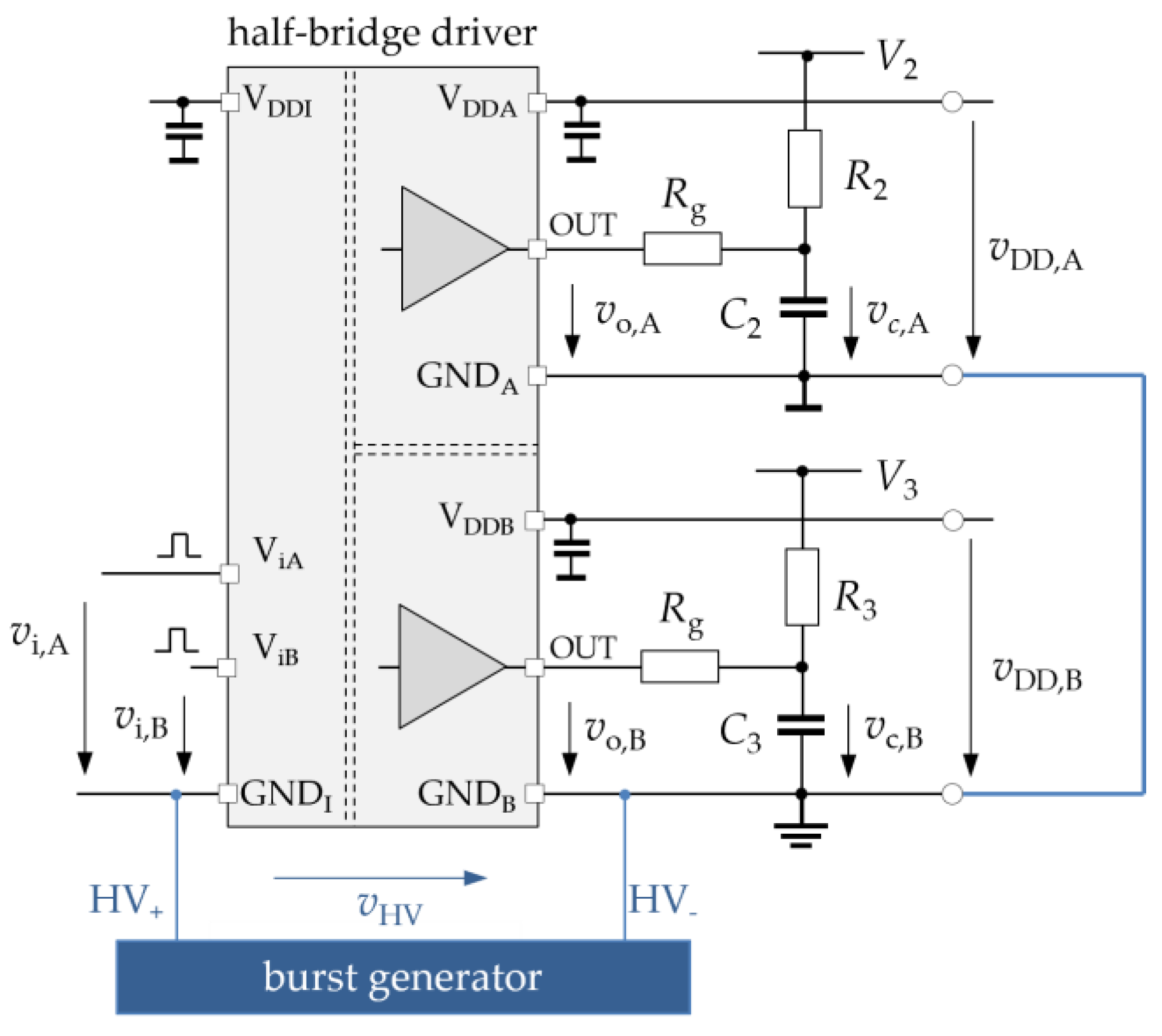

The output stage of gate drivers is usually implemented as a complementary MOSFET stage as shown in

Figure 12 in a simplified manner and in many cases with separately accessible drain terminals, which simplifies the control of the on and off times of the power transistor by means of individual gate resistors. The current source and sink capabilities of the driver directly determine the rise and fall times at a given load capacitance. Conversely, the mean output current capability can be determined from the measured rise and fall times at a fixed, known linear load capacitance:

To determine the maximum current source and sink capability of each IC, measurements were performed without an external gate resistor unless otherwise noted and using a highly stable (NP0) linear load capacitance. The source and sink capability is mainly determined by the output MOSFETs saturation characteristic and on-state resistance. Of course, any smaller gate current can be set in the application using additional external gate resistors. The designations in (1) refer to

Figure 2 but are also transferable to

Figure 4. In case of the ADUM4121 a non-zero gate resistance was used according to datasheet recommendations to avoid excessive output ringing. The same was done with the 2EDF7275F.

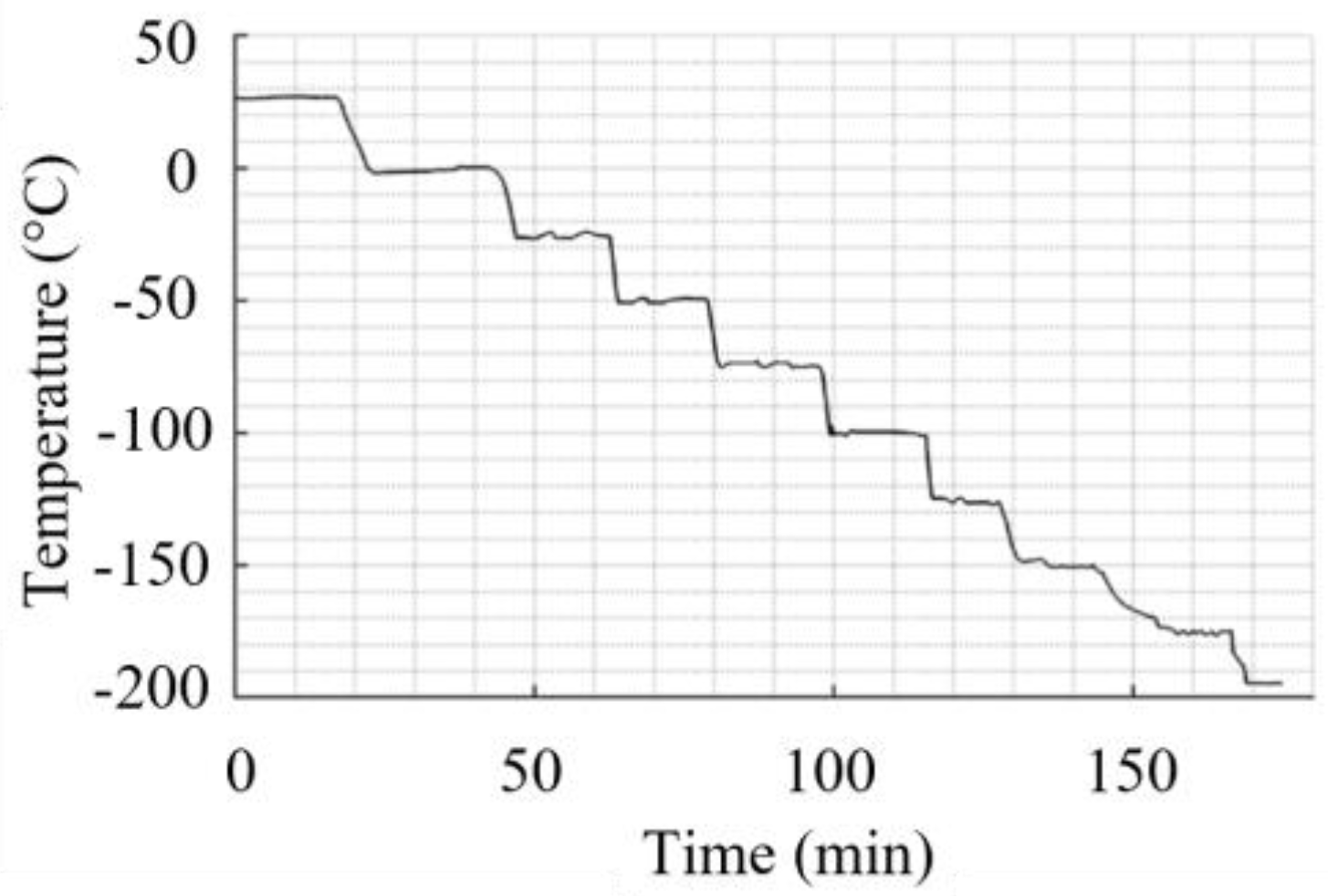

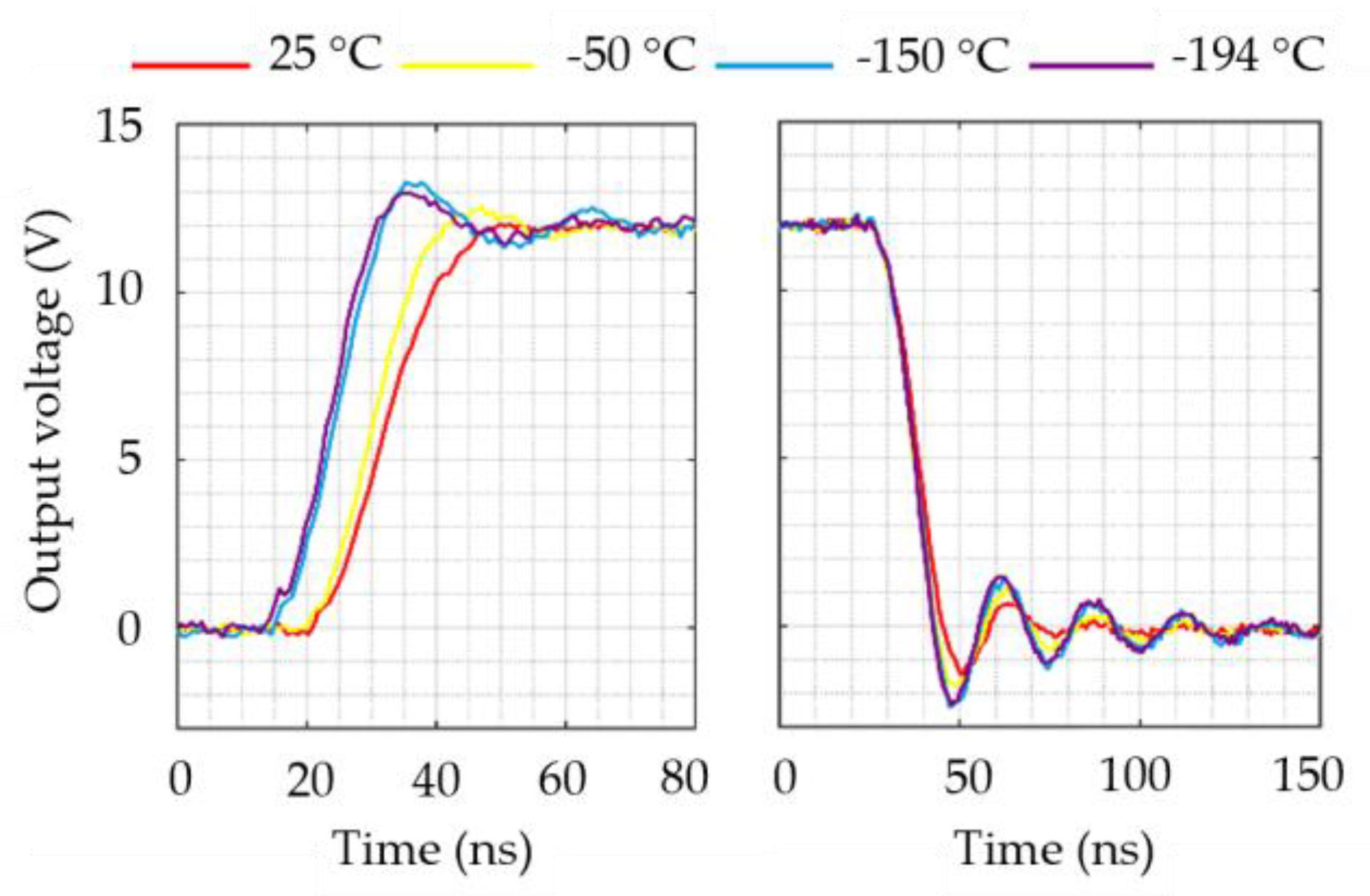

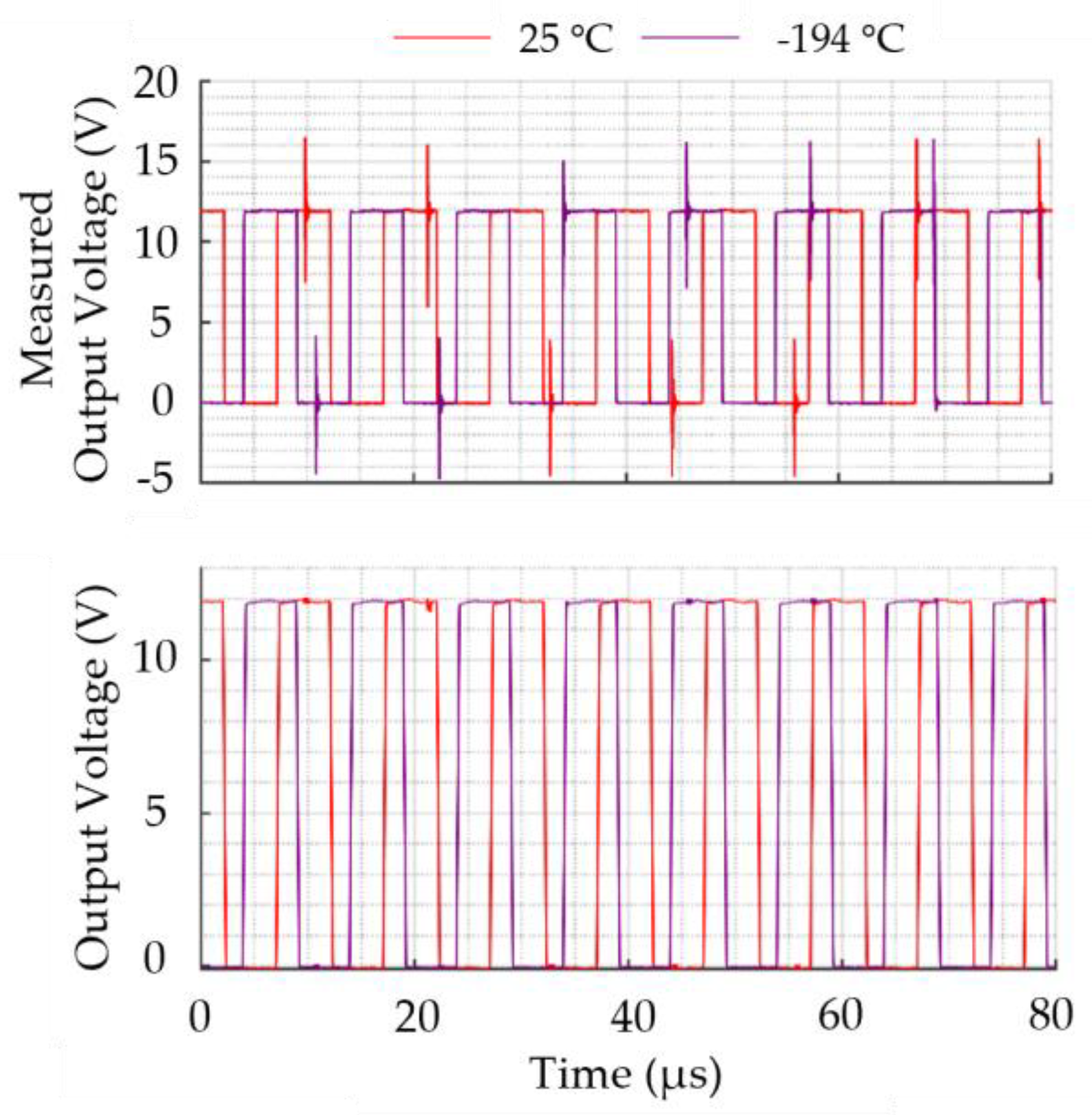

Figure 7 shows the measured temperature-dependent output voltage using the Si8271 as an example. As can be seen, the rise and fall times decrease slightly with temperature, which also results in a slightly increased ringing.

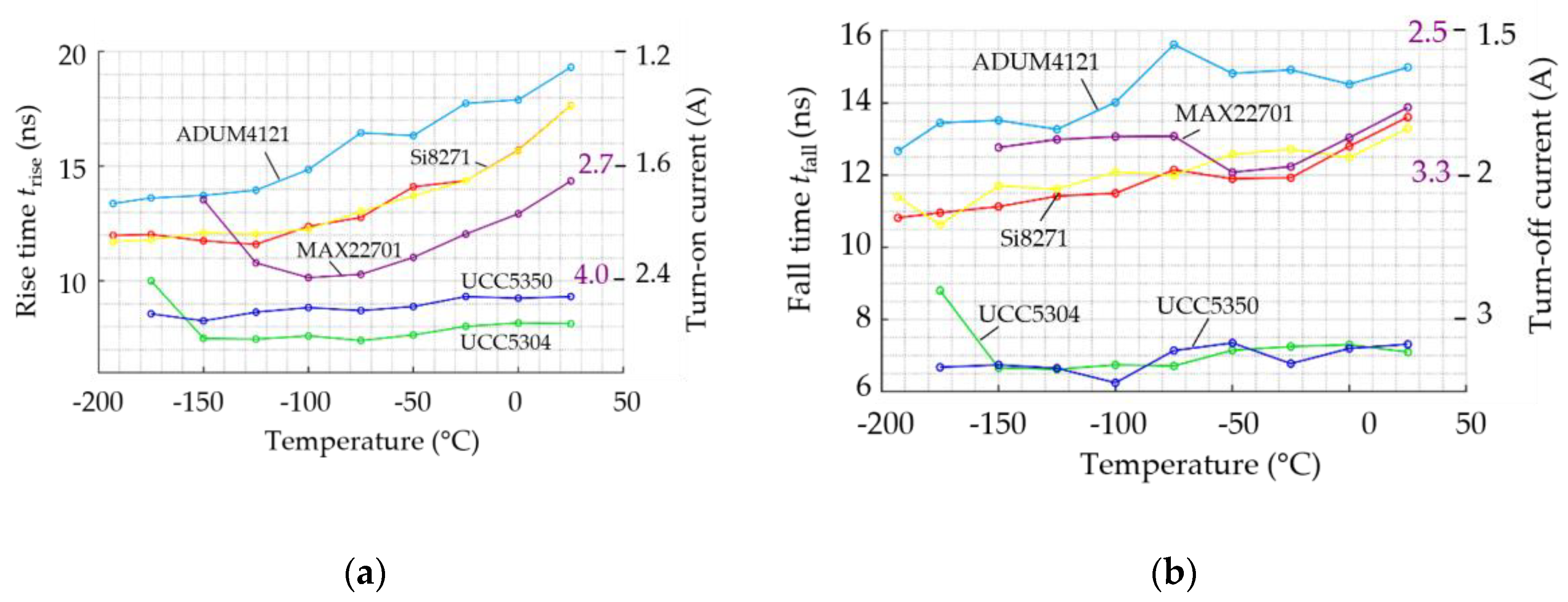

In general, as can be seen in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, most gate drivers show decreasing rise and fall times, i.e. increasing current capability with lower temperatures. In each diagram, the second y-axis (right) shows the current source and sink capability calculated from the measured rise and fall times according to (1). Please note that this is the more application-relevant average current capability and may somewhat differ from the peak current specified in the respective datasheet. The increasing current capability with lower temperatures is as expected, since with decreasing temperature the on-resistance decreases and the saturation current increases for both the p- and n-channel Si-MOSFET in the driver output stage. However, individual "outliers" also show that this general tendency can be overlaid and even reversed by influences of the complex IC-internal circuitry.

Three test results are particularly noticeable:

4.2. Propagation Delay

A driver IC comprises several functional blocks that control, amplify and transmit signals from the digital driver input to the output. The time it takes for an input signal to pass through these functional blocks is called the propagation delay. The propagation delay of a driver should be largely independent of temperature, since in general the delay is part of the control loop of a switch-mode converter. In particular, the turn-on and turn-off delay should run in parallel, otherwise the switching pulse length at the output changes over temperature compared to the time commanded at the input. This is highly undesirable, for example, when setting the dead time in a half-bridge, i.e. the period of time during which both transistors must be switched off to avoid bridge short circuits.

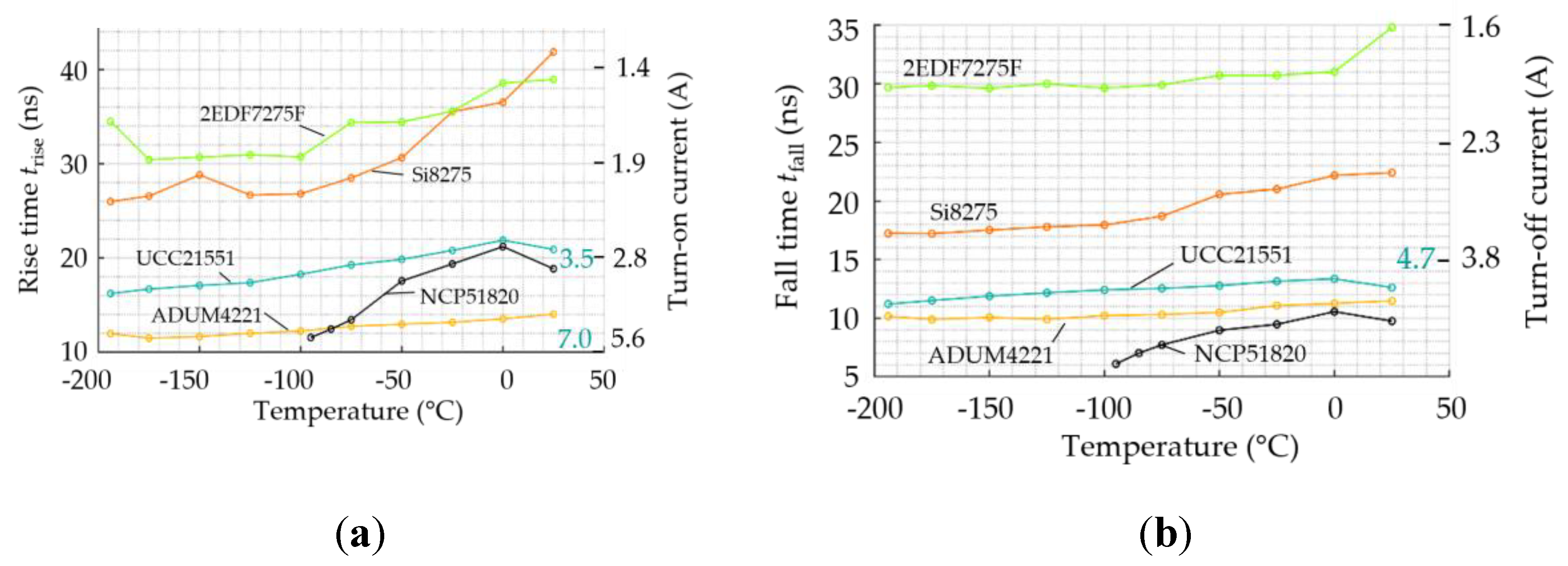

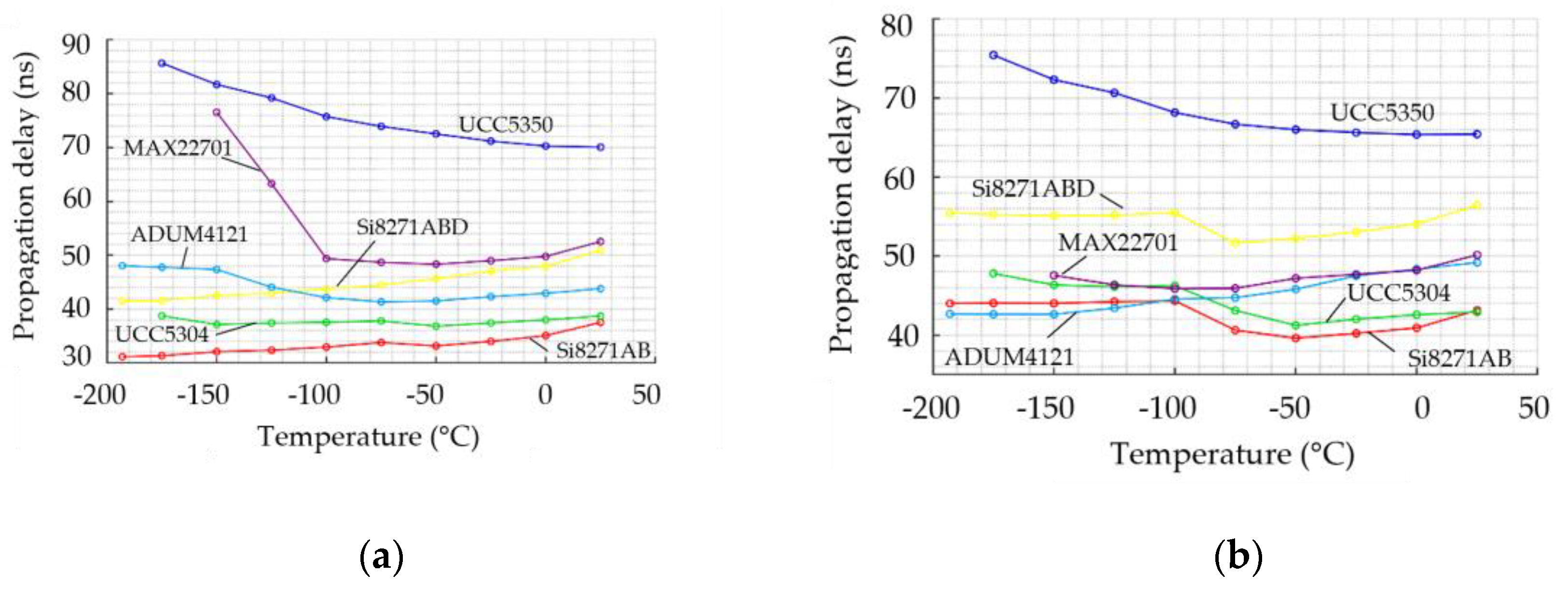

The measurement results are shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. Since the low-side channel behaved very similarly to the high-side channel, only the propagation delay of the high-side channel of the half-bridge drivers is shown in

Figure 11. If an external gate resistor had to be used, the propagation delay was measured behind

Rg, i.e. using

vc. The curves show a widely stable propagation delay with some exceptions: The turn-on delay of the MAX22701 (magenta) rises noticeable below -100 °C, while the turn-off delay shows only a slight increase. Against the general trend, the UCC5350 in

Figure 10 and UCC21551 in

Figure 11 show an increase in propagation delay towards very low temperatures. In this case, however, the measurements continue the trend already specified in the datasheet within the regular operating temperature range. As mentioned above, the MAX22701, NCP51820, UCC5304 and UCC5350 could not be characterized down to the lowest temperatures.

As can be seen, an individual experimental characterization is important because a prediction of the low-temperature behavior of the propagation delay is generally not possible without detailed information about the internal circuitry of a driver IC.

4.3. Undervoltage Lockout

An important logical function of a driver-IC, which is highly relevant for a reliable and efficient operation of the power semiconductors, is the undervoltage lockout. This internal protective function monitors the driver supply voltage (VDD or VDDA/B) and prevents inadequate control of the power transistor when the voltage is below a specified threshold. This prevents malfunctions and potential thermal damage caused by an increased on-state resistance and incomplete switching operations. For proper protection, the UVLO threshold must be selected to match the threshold window and the transfer characteristics of the power semi conductor to be controlled. To avoid oscilla tions around the UVLO threshold, this is provided with a hyste resis. This means that a higher supply voltage is required to activate the output (turn-on or positive-going threshold) than for the transi tion into the lockout state (turn-off or negative-going threshold). The UVLO function within a driver IC com prises several circuit blocks like compara tors and logic gates, each with its own temperature charac te ristic.

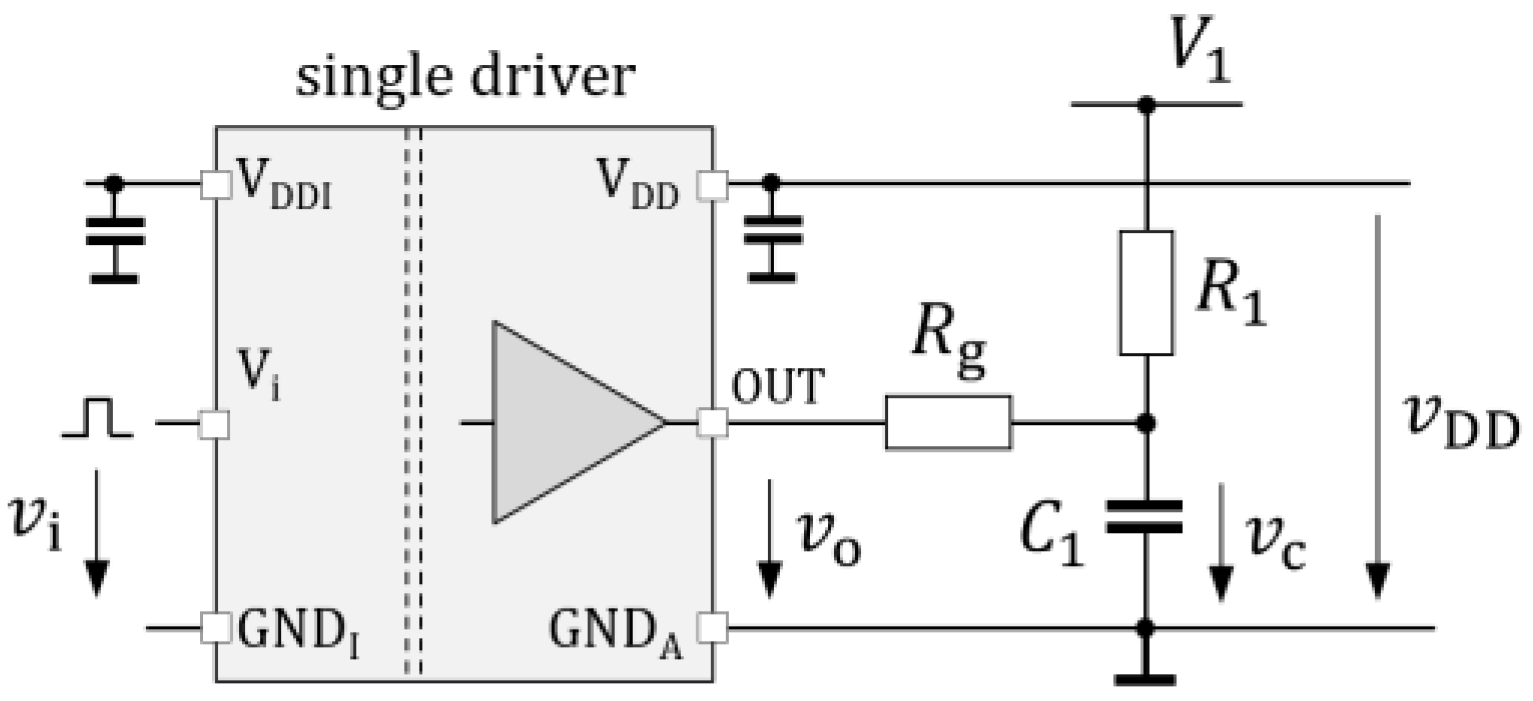

To monitor whether the driver output is able to provide a well-defined zero state when the IC is inactive, a pull-up resistor is used as illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 4. The pull-up resistor R

1/2/3 = 24 kΩ is connected to a fixed 12 V source and injects a current of about 0.5 mA simu lating a Miller effect situation.

The measured output voltage during ramping up and down of the driver supply voltage with an applied periodic input signal is shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. As can be seen, no IC is able to pull the output down to zero voltage when zero supply voltage is applied. This can be explained by

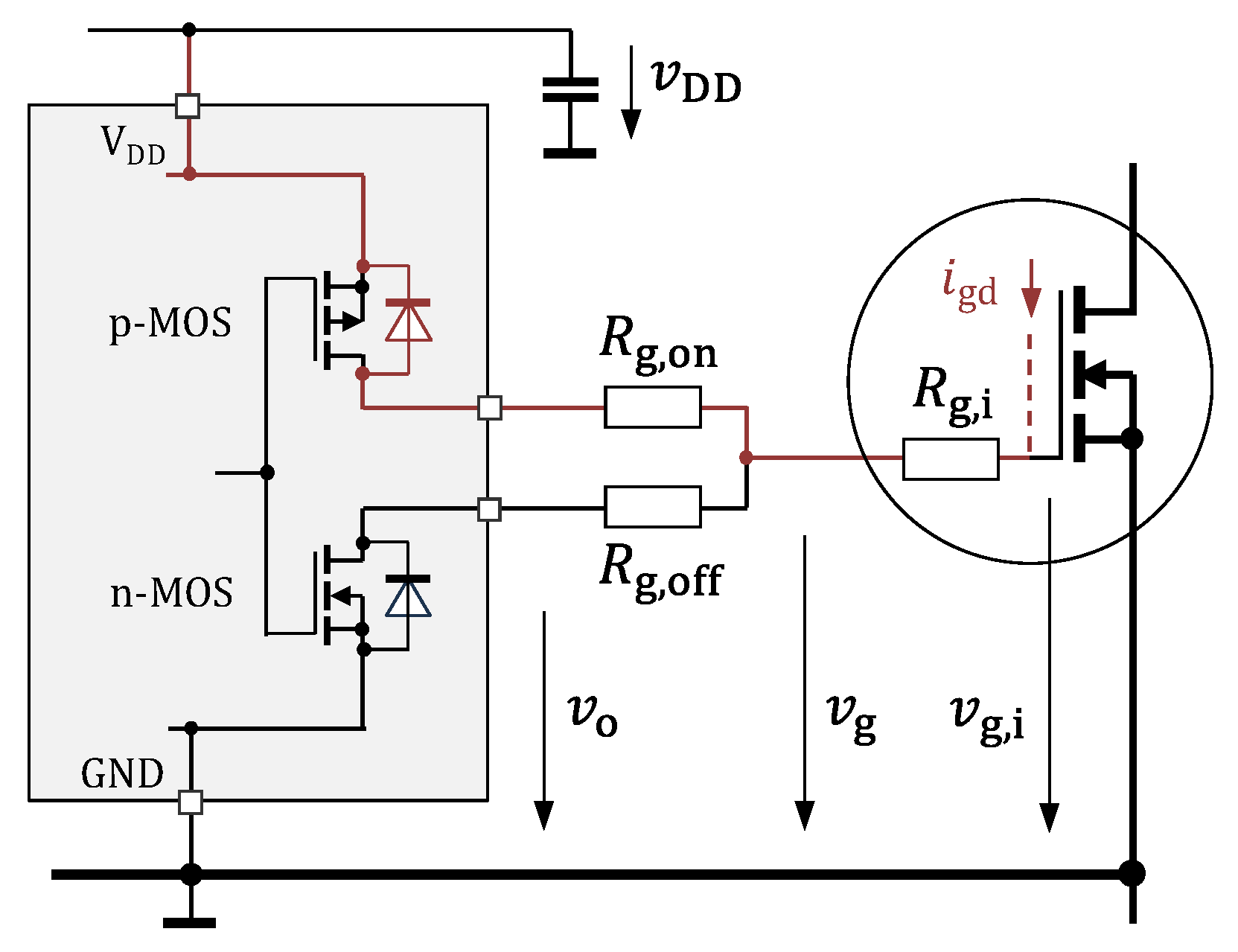

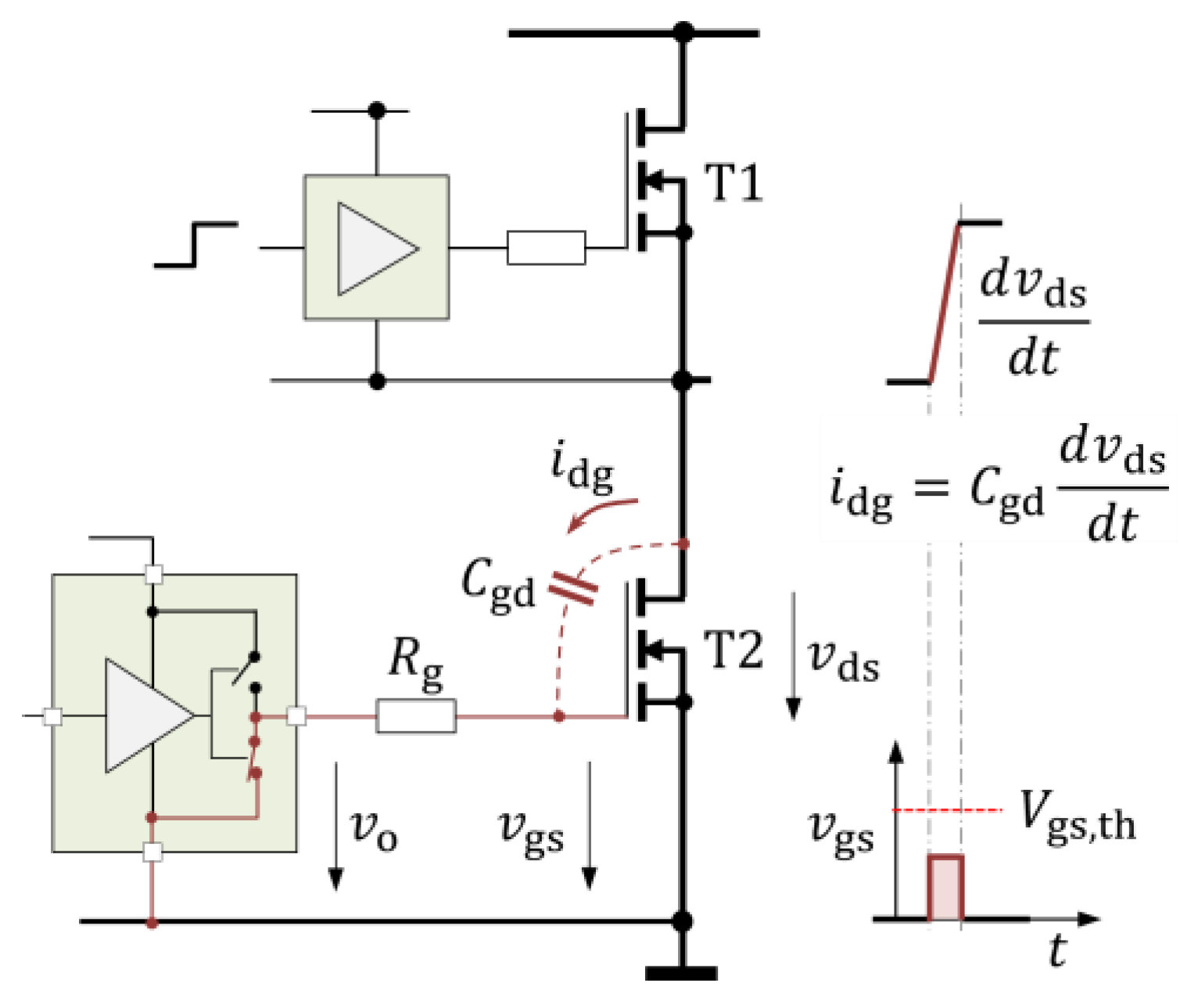

Figure 12. The diodes shown in parallel to the comple mentary MOSFETs of the driver output stage represent the intrinsic body diodes of the respective MOSFETs and are drawn with a diode symbol for illustration purposes only. As long as there is not enough voltage available to turn on neither the p-MOS nor the n-MOS in the driver out put, the injected current flows through the body diode of the p-MOS (red current path) and charges the capacitor at the driver supply pin.

Figure 12.

CMOS driver explaining the voltage situation in case of an inactive complementary MOSFET output stage.

Figure 12.

CMOS driver explaining the voltage situation in case of an inactive complementary MOSFET output stage.

In this situation, the voltage v

o at the driver output exceeds the supply voltage v

DD by the forward voltage of the body-diode. Typically for Si p/n-diodes, this forward voltage in creas es with decreasing temperature and reaches about 0.8 V at -196 °C at the low in ject ed current in this test. As can be seen from

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, depending on the driver IC, the supply voltage must rise to over 2.5 V, before the n-MOS can be activated and the output is actively pulled to zero. The minimum supply voltage required for this in creases with decreasing tem pe ra ture, as does the threshold voltage of the n-MOS.

Notable exceptions are the single drivers UCC5304, UCC5350 and MAX22701 as well as the half bridge drivers 2EDF7275F and UCC21551. These obviously con tain an additional clamping circuit that ensures that the output voltage is limited already in this supply voltage range. However, even these devices cannot safely limit the output voltage to values below 1 V, even against the very low injection current chosen for the tests.

The floating state output voltage levels vary from approximately 1.0 V to 1.8 V at room tem pe rature to 1.5 V to 2.8 V at -194 °C. A similar behavior is observed in all drivers as the driver voltage decreases. Below a certain supply voltage, the driver is no longer able to apply an active zero state to its output.

A short numerical example should illustrate the problem: Assume that the power MOSFET has a Miller capacitance of Cgd = 20 pF and a dvds/dt = 50 V/ns occurs. Then a current idg = 1A is injected causing a voltage drop of 2 V across a typical chip internal gate resistance of Rg,i = 2 Ω. If the driver now allows an output voltage of 2.5 V when there is no or insufficient supply voltage, a voltage vg,i of 4.5 V occurs at the inner MOSFET gate, which already ex ceeds the typical threshold voltage of Si and SiC MOSFET. If there is an addi tio nal external gate resistor (Rg,on) in the circuit, the situation becomes even worse, and a parasitic turn-on be comes un avoidable. This problem becomes even more dramatic when GaN HEMTs with their low threshold voltage levels are to be controlled.

As soon as the driver's internal logic becomes functional, the output is actively pulled to zero. In the subsequent voltage range until the UVLO turn-on threshold is reached, no impermissible switching operations at the output (glitches) could be detected over the entire temperature range, for all drivers tested except the ADUM4221 (see

Figure 14 (b)). The latter showed a pronounced malfunction near the UVLO threshold at very low temperatures with impermissible switch ing operations and phases in which the output stage is even deactivated again, which, as with supply voltages close to zero, becomes noticeable in output voltages above the driver supply voltage.

Immediately at the UVLO turn-on and turn-off threshold, all gate drivers showed a pulse shortening due to a lack of synchronization between the UVLO enable of the output and the control or input pulses. From an application point of view, however, this is generally not critical issue.

Above the UVLO threshold and within the functional temperature range shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, all drivers pro vided regular output pulses with a level corres ponding to the driver supply voltage. At the frequency of 1 kHz used for the tests, these pulses are only visible as colored areas in the diagrams. However, the integrity of the output pulses within the regular operating range, i.e. above UVLO, was verified in all cases, especially at low tempe ra tures.

As can be seen from

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, the power-up and down behavior of all drivers examined is largely sym me tri cal. The non-linear decay of the supply voltage is due to the property of the programmable DC voltage source used, which could pro vide very small output voltages only with limited dynamics due to the lack of active sink capability. However, this shape is very close to the real supply voltage curve in an application after power-off.

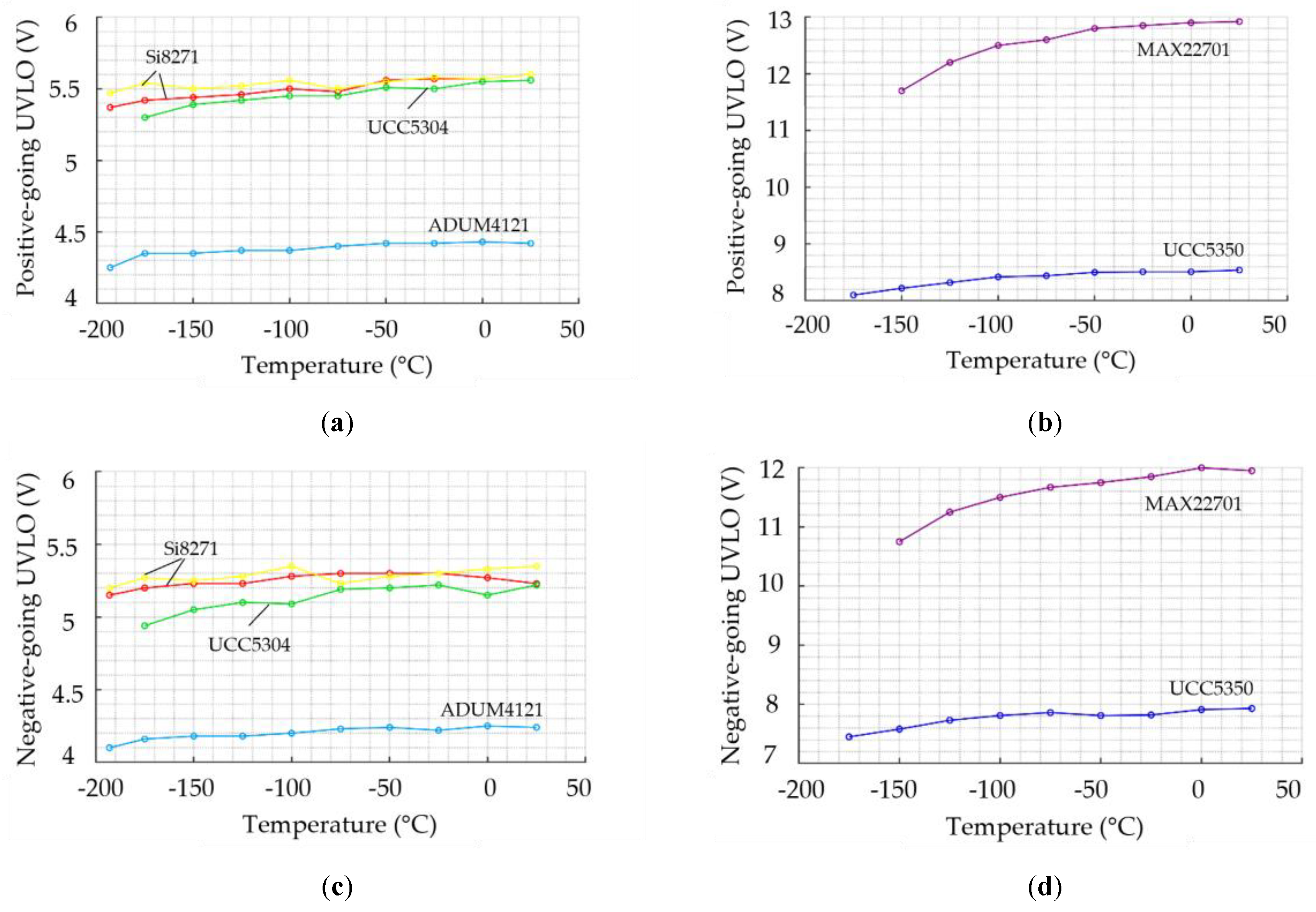

In addition to investigating the behavior of the output stage within the UVLO operating range, an important objective of this test was to analyze the temperature de pendence of the driver's UVLO threshold. The dashed lines in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 give the UVLO threshold range as speci fied in the respective datasheet for room temperature. An overview of the test results for both the positive and negative-going UVLO thresholds as a function of tempe ra ture is presented in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Positive-going (a,b) and negative-going (c,d) UVLO threshold of the single drivers over temperature.

Figure 15.

Positive-going (a,b) and negative-going (c,d) UVLO threshold of the single drivers over temperature.

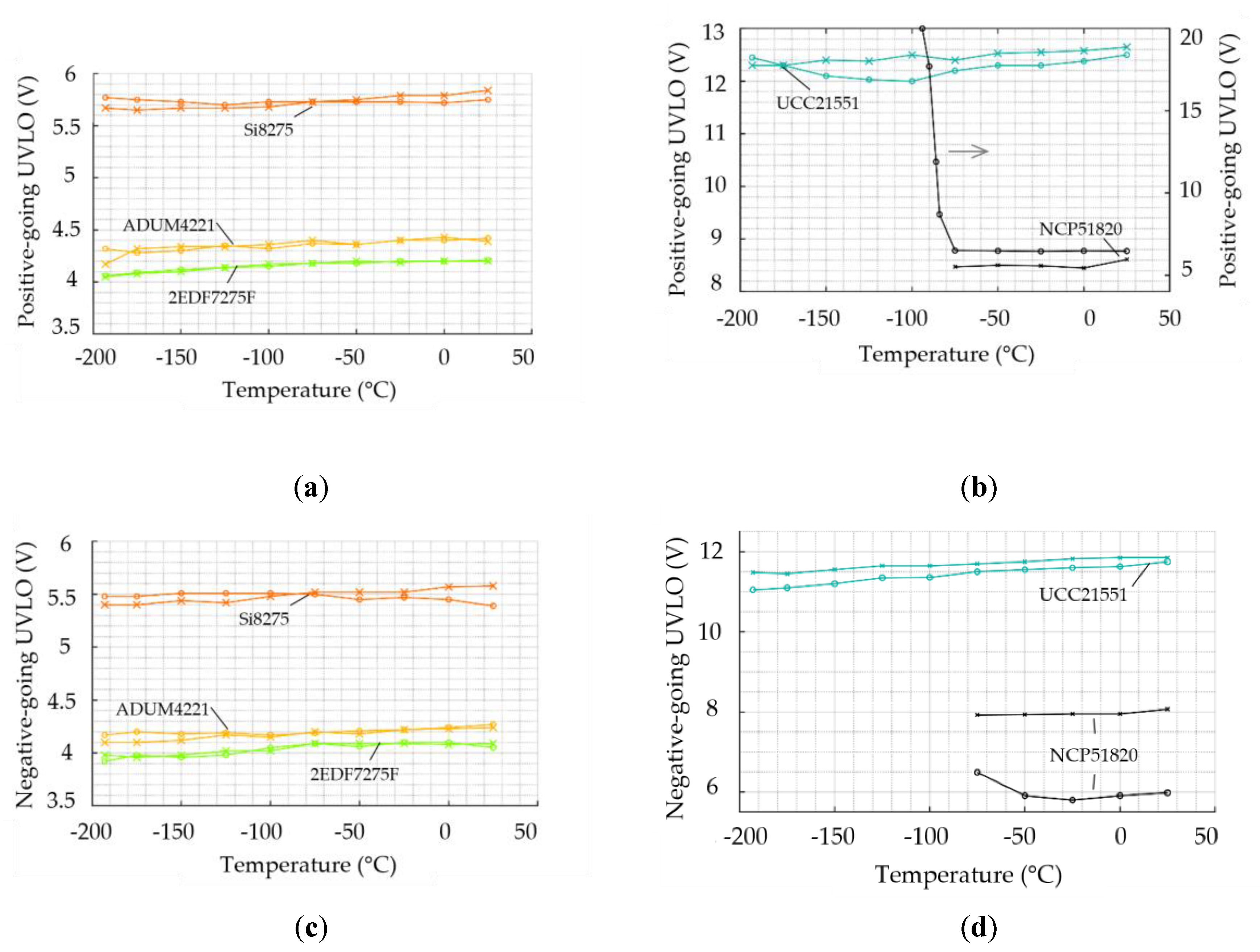

Figure 16.

Positive-going (a,b) and negative-going (c,d) UVLO threshold of half bridge drivers over temperature (marker: “o” High Side, “x” Low Side).

Figure 16.

Positive-going (a,b) and negative-going (c,d) UVLO threshold of half bridge drivers over temperature (marker: “o” High Side, “x” Low Side).

All drivers, except the NCP51820, show a slight, in case of the MAX22701 a more pronounced, de crease in the UVLO thresholds as the tem pe rature decreas es. Overall, however, the UVLO thres holds of all incon spic uous drivers are found to be remark ably stable. Nevertheless, from an application engineering point of view, a slight increase in the UVLO threshold values as the temperature decreases, corres pond ing to the increase in the threshold voltage of the power components, would be desirable.

The half-bridge driver NCP51820 is based on level shifter technology and the only tested device without galvanic iso lation. This device was included because it is specifically announced as a driver designed to meet the requirements for GaN transistors and therefore could be attractive for cryo genic GaN applications. Unfortunately, the driver failed at liquid nitrogen temperatures. As can be seen from

Figure 16 (b), the problem is probably due to the UVLO threshold running away below -75 °C. At -95 °C, the UVLO threshold already exceeds the maximum driver supply voltage.

The two drivers Si8271AB and Si8271ABD behave simi lar ly regarding their UVLO behavior (s. Figures 13 (a/b) and 15 (a/c)). The designation "D" in the name stands for a "de glitch" variant. However, the tests did not reveal any influence of this variant on the UVLO behavior.

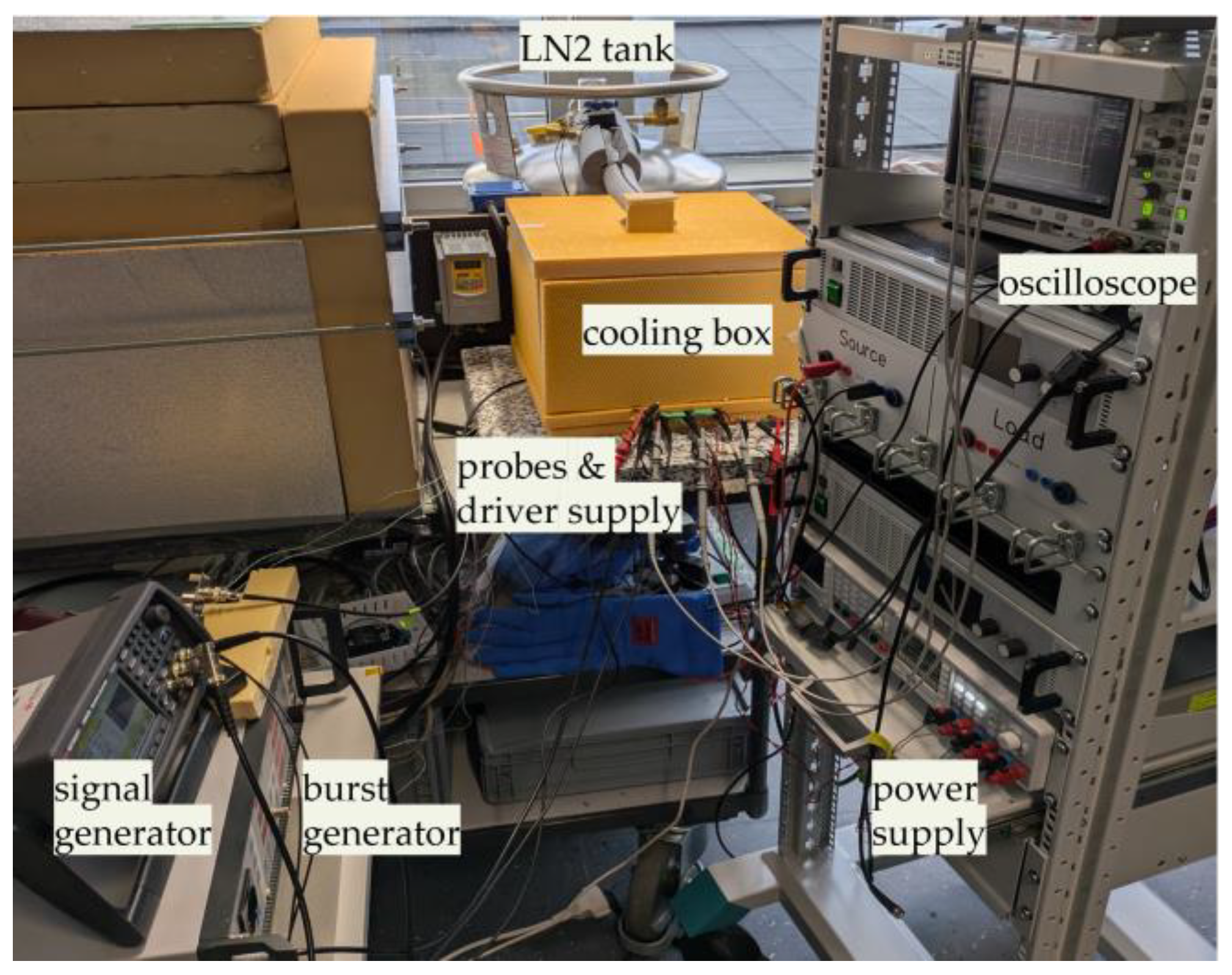

4.4. Common Mode Transient Immunity

A high CMTI (Common Mode Transient Immunity) is crucial for isolating gate drivers, especially when used to operate modern fast switching power semiconductors. It is essential that the driver's CMTI value exceeds the maximum voltage gradients on the floating power transistor. When using cryogenic power electronics, the CMTI requirements even increase due to the higher switching speed of GaN and Si FET at lower temperatures. As measurement results indicate, the speed of GaN-HEMT at cryogenic temperatures can nearly double from 70 V/ns to 130 V/ns compared to its performance at room temperature [

13]. Modern drivers such as Si827x or MAX22701 are specified with a CMTI of up to 300 V/ns.

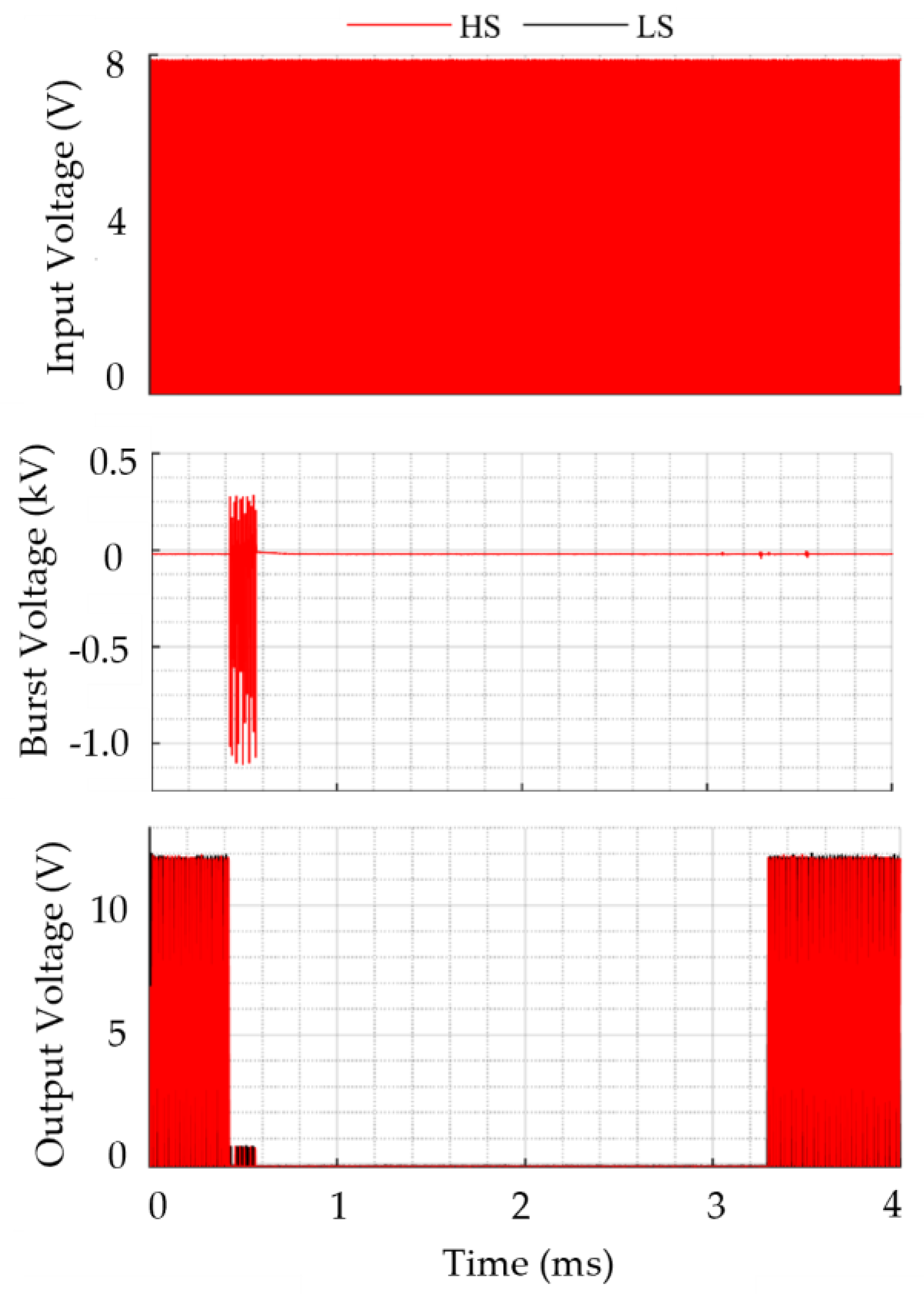

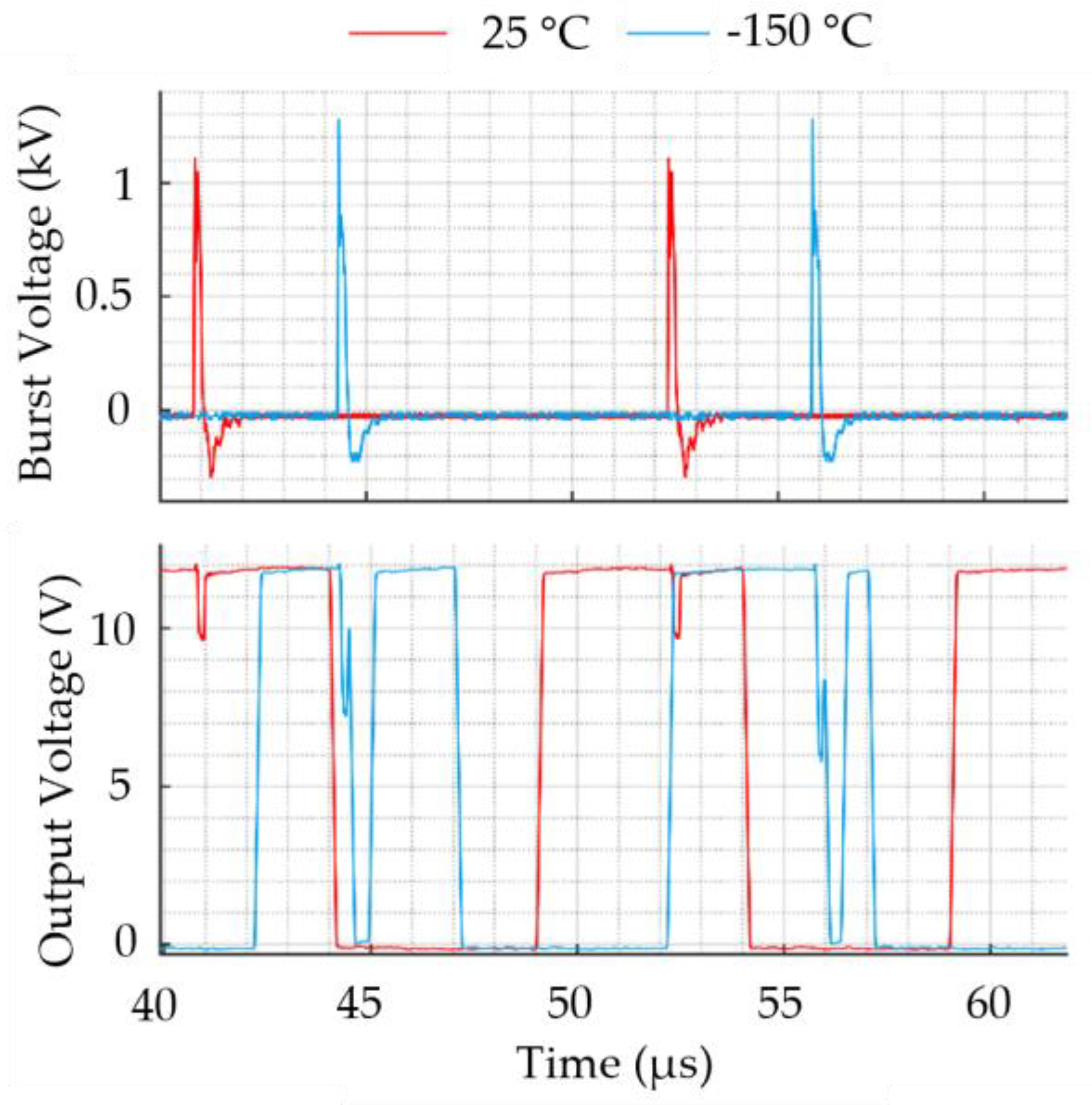

Since only output pulses from the CMTI tests are presented in the following figures, one detailed measurement result illustrating the evaluation of the CMTI behavior is shown in

Figure 17 using the ADUM4121-1ARIZ. Beside the driver input voltage at room temperature and at -194 °C, this figure shows the burst voltage (v

HV) as well as the driver output signal during one burst period. In later figures only the burst signal and the output signal are shown. Please note: Since in the present test setup the reference potential of the burst generator is at the output of the drivers (see

Figure 4), positive voltage pulses cause a negative dv/dt at the rising edge according to the usual definition related to the primary side.

During burst measurements with voltages up to 2500 V, significant noise superimposes the measured output voltage as shown in

Figure 18. With extensive investigations (short-circuited probes, etc.) we were able to verify that this noise is caused by interference coupled into the measurement setup and is not present in the output signal.

In order to improve the interpretation of the results with regard to possible faulty switching states, a low-pass filter with a sufficiently high cutoff frequency was used to attenuate the very high ringing frequencies. Depending on the CMTI value specified in the data sheet, tests were carried out at each temperature level with burst voltages between 1 kV and 2.5 kV. With a rise/fall time of the burst pulses in the range of 5 to 7 ns this results in voltage transients dv/dt in the range of 100 V/ns up to 350 V/ns.

Before discussing some drivers in detail, the following findings of the CMTI measurements can be summarized:

The CMTI specification according to the datasheet was verified for almost all drivers at room temperature. Irregularities were detected in the Si8275 half-bridge driver at negative transient voltages (see

Figure 19 and

Figure 20).

Within the specified CMTI value, the following drivers showed no irregularities over the entire temperature range from room temperature to -194 °C (comparable to

Figure 17): Si8271AB/D, 2EDF7275F, ADUM4121, ADUM4221, UCC5350 and UCC5304 (for the latter two, see also the mentioned parameter scatter with respect to the low-temperature functional limits)

For the MAX22701, a short-term shutdown of the output signal was observed also at 0 °C and +100 V/ns, i.e. within the specified CMTI range (typ. 300 V/ns), see

Figure 21.

With decreasing temperature, and transient voltages exceeding the specified CMTI, some drivers tend to higher voltage drops, temporary OFF states, or even driver damage: UCC5304, UCC5350 and UC21551.

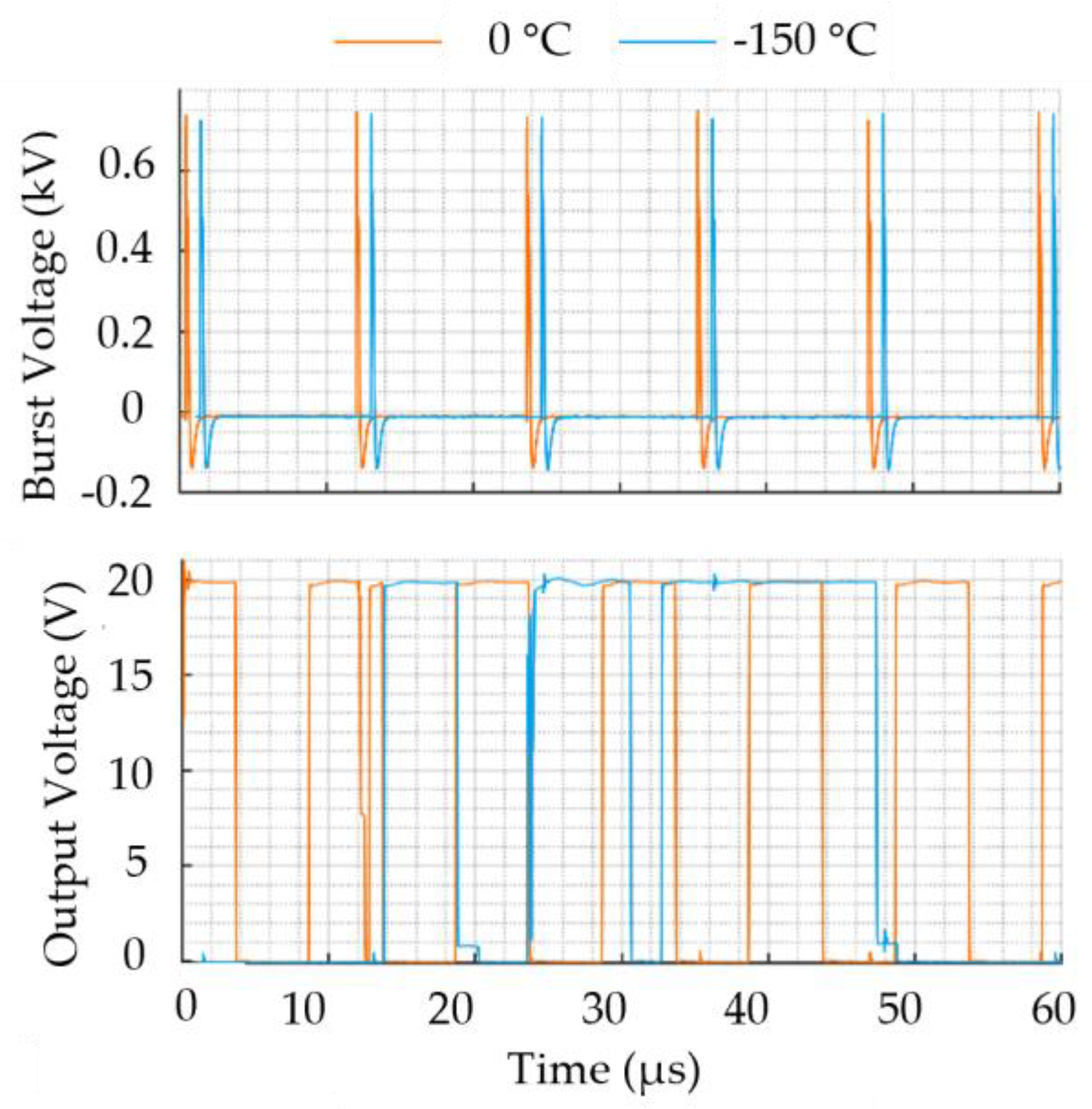

While all other drivers tested were unremarkable at room temperature, the half-bridge driver Si8275 showed a conspicuous error pattern: Specified in the datasheet as “min. 200 V/ns, max. 400 V/ns”, the driver behaved correctly at 250 V/ns during positive transients, but a strange malfunction was observed during negative transients (see

Figure 19).

Depending on the burst amplitude, this ranged from a brief deactivation of the HS and LS output signals within a single signal period (e.g. 130 V/ns at -1.4 kV burst, see

Figure 20) to a complete interruption of the output signals for a significant period after a burst event. For instance, at -0.5 kV, the output signal was interrupted for 220 ms, while at -1.1 kV, as illustrated in

Figure 19, the interruption was significantly reduced to 3.3 ms. Due to the long measurement time, both the input and output signal can only be seen as colored areas and no longer as pulses. The output signal automatically resumed following this interruption, this applies to both the high-side (HS) and low-side (LS) outputs. Measurements conducted with replacement drivers from two different production batches, 2021 and 2024, showed consistent behavior. At negative transients exceeding 120 V/ns, malfunctions characterized by brief output deactivation were consistently observed across the entire temperature range down to -194 °C.

Within the typical CMTI specification, some drivers showed correct functioning across the entire temperature range from room temperature to -194 °C, under both negative and positive dv/dt conditions: This applies to the following drivers and the corresponding applied transient voltages: Si8271AB/D (±300 V/ns), 2EDF7275F (±300 V/ns), ADUM4121 (±200 V/ns), ADUM4221 (±170 V/ns), UCC5350 (±140 V/ns) and UCC5304 (±140 V/ns).

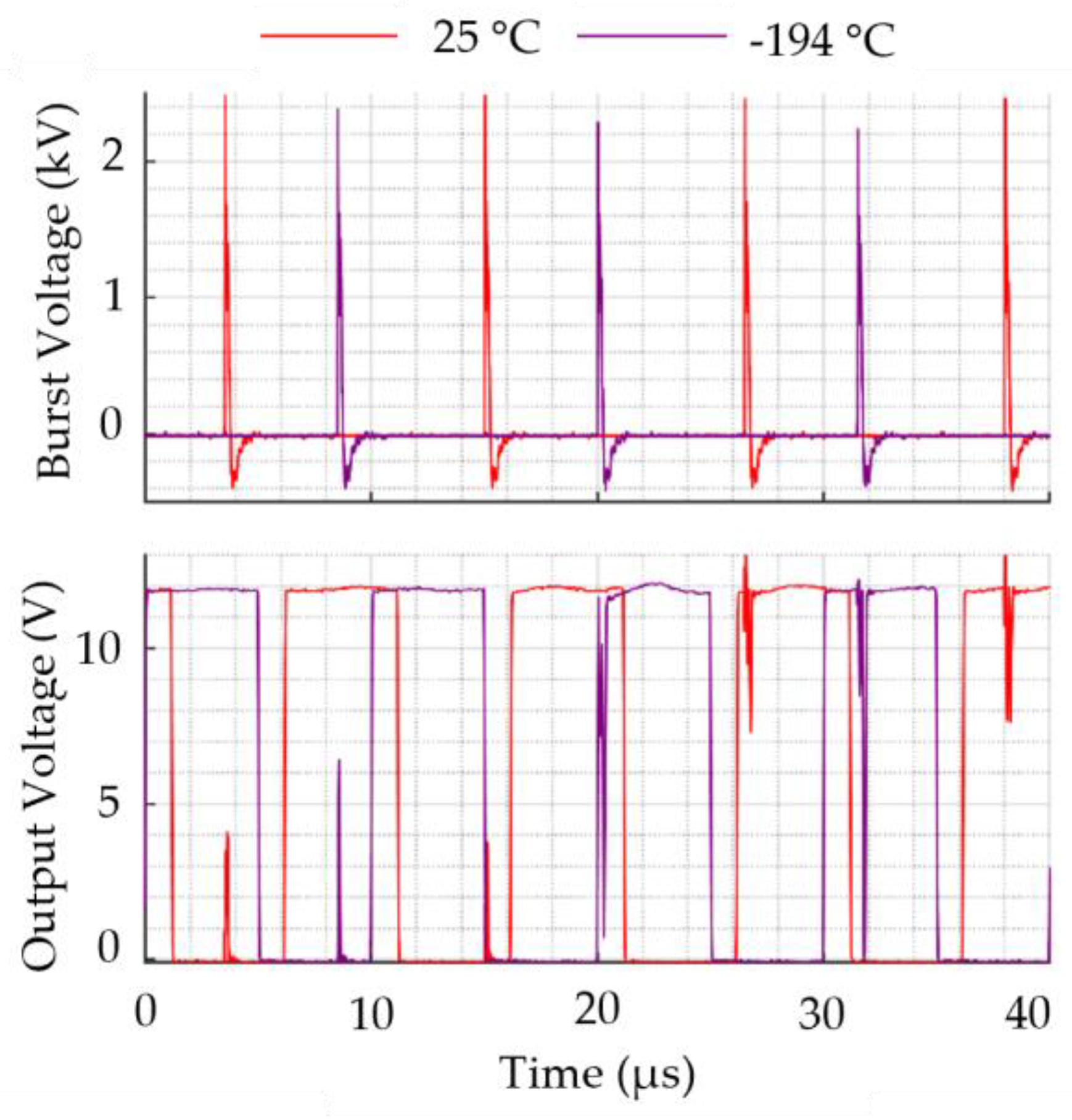

The CMTI behavior of the MAX22701 driver differed from that of the previously mentioned drivers. Within its specified typical CMTI of 300 V/ns, short-term deactivation of the output signal was already observed at 0 °C and positive transients with 100 V/ns, as illustrated in

Figure 21 at 12 µs. At -150 °C, undefined output pulses occurred, and even after warming up to room temperature, the driver remained non-functional.

In general, interference on the driver output signal could be observed at high dv/dt values that approached or exceeded the specified maximum value. These were typically incomplete turn-on or turn-off operations with a duration of up to several hundred nanoseconds which is shown in

Figure 22 as an example. At -194 °C, the Si8271 showed short turn-off events at positive transients of 350 V/ns, while at negative transients of the same steepness no false ON/OFF states were observed over the entire temperature range.

Some drivers showed permanent damage when the maximum specified dv/dt was exceeded, despite careful care not to exceed the maximum specified voltage amplitude. The UCC5304, e.g., showed irregularities at the output at -150 °C and +100 V/ns, after voltage transients of up to ±300 V/ns were applied at each temperature level during the cooling process (s.

Figure 23). When the device was stressed exclusively with transients within the specification of ±130 V/ns, no irregularities were observed across the entire temperature range.

A similar behavior was observed with the UCC5350 (rated at typ. 120 V/ns). Starting at room temperature with transients exceeding 200 V/ns, no more output pulses were detected at -150 °C, and functionality did not recover upon reheating to room temperature. After replacing the driver and limiting the transient voltage to ±130 V/ns at each temperature level, proper functionality was maintained down to -194 °C.

The UCC21551 with a dv/dt rating >125 V/ns exhibited a similar behavior too. At -100 °C and +170 V/ns, missing and shortened pulses were detected, as shown in

Figure 24. When voltage transients of up to ±200 V/ns were applied to the driver at each temperature level, no output signal was produced at -125 °C and below. CMTI measurements with approx. ±70 V/ns over the entire temperature range did not show any effects on the output signal.