1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer ranks as one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide, holding the third position globally and second in Romania. According to WHO (World Health Organization), more than 1.9 million new cases were recorded worldwide in 2020, with Romania reporting 12,968 new cases [

1]. Globally, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality

. Therefore, a more accurate analysis of its pathogenesis, particularly the molecular profile of this disease, is essential [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

The incidence of colorectal cancer is higher in men than in women and occurs more frequently after the age of 50. However, elderly individuals have a significantly higher predisposition to developing this disease [

4,

6,

7,

8,

9].

In 1990, Bufill first described two distinct categories of colorectal tumors: right-sided and left-sided tumors, each with different molecular and clinical characteristics. These hypotheses have been further supported by numerous contemporary studies, which have provided clearer distinctions in the molecular behavior of colorectal tumors. The most plausible explanation for this difference lies in the distinct embryological origins of the colon, with the right colon deriving from the midgut and the left colon from the hindgut and also in the blood supply [

10,

11]. Based on this classification, the right colon includes the cecum, ascending colon, and the first two-thirds of the transverse colon, whereas the left colon consists of the distal third of the transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon [

10,

11,

12].

Colorectal cancer is an oncological pathology that arises from various alterations, which may be the consequence to external factors (such as diet, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption) as well as internal factors, either hereditary or resulting from changes in intracellular signaling pathways causes by genetic and epigenetic alterations [

6,

13].

Significant differences in the molecular profiles of colorectal cancer patients have been identified, influencing tumor development. Women are more likely to develop tumors in the right colon, while men more frequently present with tumors in the left colon [

10,

14,

15]. Clinically, right-sided colon tumors tend to be larger and are often associated with anemia and rapid weight loss. In contrast, left-sided colon tumors are typically more infiltrative, commonly leading to rectal bleeding and bowel obstruction [

10,

14,

15,

16]. Building on Bufill’s study, recent research has further demonstrated that right-sided colon tumors exhibit higher activation of the MAPK and mTOR pathways, microsatellite instability, and the CpG island methylator phenotype. In contrast, left-sided colon tumors show activation of the EGFR/Wnt pathway and chromosomal instability.[

10,

14,

15].

The most significant signaling pathways involved in the development of colorectal cancer are the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway and the PI3K/PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway, both of which are activated by a ligand binding to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [

6,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Their activation leads to uncontrolled cell proliferation, increased cellular motility, and resistance to programmed cell death. Key proto-oncogenes associated with these pathways include members of the RAS family (KRAS, NRAS, HRAS) and PIK3CA [

6,

17,

18,

19,

20].

In colorectal cancer, the most frequent mutations are observed in KRAS gene (Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog), found in approximately 45% of cases, followed by the NRAS gene (neuroblastoma rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog), in about 5% cases, and PIK3CA gene, in 10% of the cases [

6,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Mutations in the proto-oncogenes KRAS and NRAS are commonly located in exon 2 (codons 12 and 13), exon 3 (codons 59 and 61), and exon 4 (codons 117 and 146) [

6,

17].

Microsatellites are small repeating stretches of DNA scattered throughout the genome, making them particularly susceptible to mutational changes. The DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system is a crucial mechanism responsible for correcting errors that occur during DNA replication. Microsatellite instability (MSI) refers to mutations in mismatch repair genes, leading to alterations to the DNA sequence [

18,

21,

22,

23,

24].

This MMR system consists of the following genes mutL homolog 1 (MLH1), mutS homolog 2 (MSH2), mutS homolog 6 (MSH6), postmeiotic segregation increased 2 (PMS2). Depending on the number of affected genes, microsatellite instability is classified as follows: MSI-H (Microsatellite Instability-High): When two or more genes are mutated, MSI-L (Microsatellite Instability-Low): When only one gene is affected, MSS (Microsatellite Stable): When no genes are affected [

18,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Microsatellite instability is identified in approximately 15% of colorectal cancer (CRC) cases, with its prevalence varying by disease stage. In stage II CRC, around 20% of patients exhibit deficient mismatch repair (dMMR)/MSI-high (MSI-H). This proportion decreases to approximately 12% in stage III and further declines to around 4% in stage IV, where MSI is least common [

21,

24,

25].

Aim and Scope

Considering recent advancements in oncology, particularly in genetic mutations and targeted therapies, investigating novel biomarkers in relation to clinicopathological data has become essential. Such biomarkers could aid in the earlier detection of colorectal cancer and provide valuable insights into its molecular profile.

This study aims to analyze the clinicopathological characteristics of colorectal cancer, focusing on the correlation between KRAS and NRAS mutations and MSI/MMR status in a cohort of patients from Romania.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Selection

Between January and June 2024, we selected all patients with a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of colorectal cancer who presented to a pathology laboratory with extensive experience in this field. The Resident Laboratory serves a broad geographical area of Romania and conducts analyses for Full RAS, NTRK mutations, and MMR status. A cohort of 262 patients were included in our study; however, among these, only 120 patients exhibited KRAS and NRAS mutations as well as alterations in MMR status.

All tissue samples were obtained from hospitals where patients had undergone diagnostic investigations and received a confirmed diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients. All the specimens were transported under proper conditions and processed at the Resident Laboratory.

This study was conducted in full accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Local Ethics Commission for Clinical and Research Developmental Studies (Approval No. 11/20.12.2024).

2.2. Method

The samples were processed by a team of highly trained technicians and assistants and subsequently examined by experienced pathologists specializing in this field.

Tissue samples (biopsies, or surgical tumoral resections) collected from patients with colorectal malignancies were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin.

To detect KRAS/NRAS mutations, NTRK alterations, and MSI status, the Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) system was employed using the Verti™ 96-Well Thermal Cycler, following the instructions outlined in the protocol . Steps of real-time PCR for the qualitative detection:

Denaturation: The reaction mixture is heated to 94 degrees Celsius, where the DNA is denatured into two strands (26)

Primer Annealing: The temperature is lowered to 50-70 degrees Celsius, during which the primers bind to complementary sequences at the ends of the two strands (26).

DNA Elongation: At a temperature of 72 degrees Celsius, the thermostable polymerase synthesizes the DNA amplicon [

26].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All data were introduced in Microsoft Office Excel 2016, and the results were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 26 (SPSS 26). The data were organized into ordinal or nominal variables. The obtained results were evaluated using chi-square tests, Pearson coefficients, and Eta coefficients. A p-value of less than 0.005 was considered statistically significant, with a 95% confidence interval.

3. Results

3.1. Clinico-Pathological Aspects of Patients with Colorectal Cancer

We analyzed a cohort of 120 patients, from western, northwestern, and central regions of Romania, with sporadic cases from other areas of the country. The prevalence of colorectal cancer was higher among males, accounting 66.7% cases, compared to females, who represented 33.3% (Tabel 1). Regarding the age of onset, the majority of cases were observed in the 71–80-year age group (35%), closely followed by the 61–70-year age group (Tabel I). Rectal tumors were the most frequently encountered, 42.5%, followed by tumors in the right colon (cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon) and left colon (splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon) which were equally distributed (27.5%) (Tabel I). Histologically, all cases were adenocarcinomas. In terms of tumor grading, the majority were moderately differentiated (G2), representing more than three-quarters of all cases (80.8%). Another important parameter assessed was the disease stage (Tabel I). Unfortunately, the majority of cases were stage IV, representing almost two-thirds of all included patients.

Table 1.

Clinico-pathological aspects of the patients with CRC.

Table 1.

Clinico-pathological aspects of the patients with CRC.

| Clinico-pathological aspects of patients with CRC |

Number (percentage %) |

Gender:

Male

Female |

80 (66.7%)

40 (33.3%) |

Age by decade:

30-40

41-50

51-60

61-70

71-80

81-90 |

4 (3.3%)

11 (9.2%)

17 (14.2%)

39 (32.5%)

42(35%)

7 (5.8%) |

Localization:

Right colon

Left colon

Rectum

Metastasis (with occult primary tumor) |

33 (27.5%)

33 (27.5%)

51 (42.5%)

3 (2.5%) |

Tumor grading:

G1

G2

G3

G4 |

7 (5.8%)

97 (80.8%)

15 (12.5%)

1 (0.8%) |

Stage:

I

II

III

IV |

0

4 (3.3%)

40 (33.3%)

76 (63.3%) |

3.2. KRAS, NRAS Mutations and MMR Status in the Studied Patient Cohort

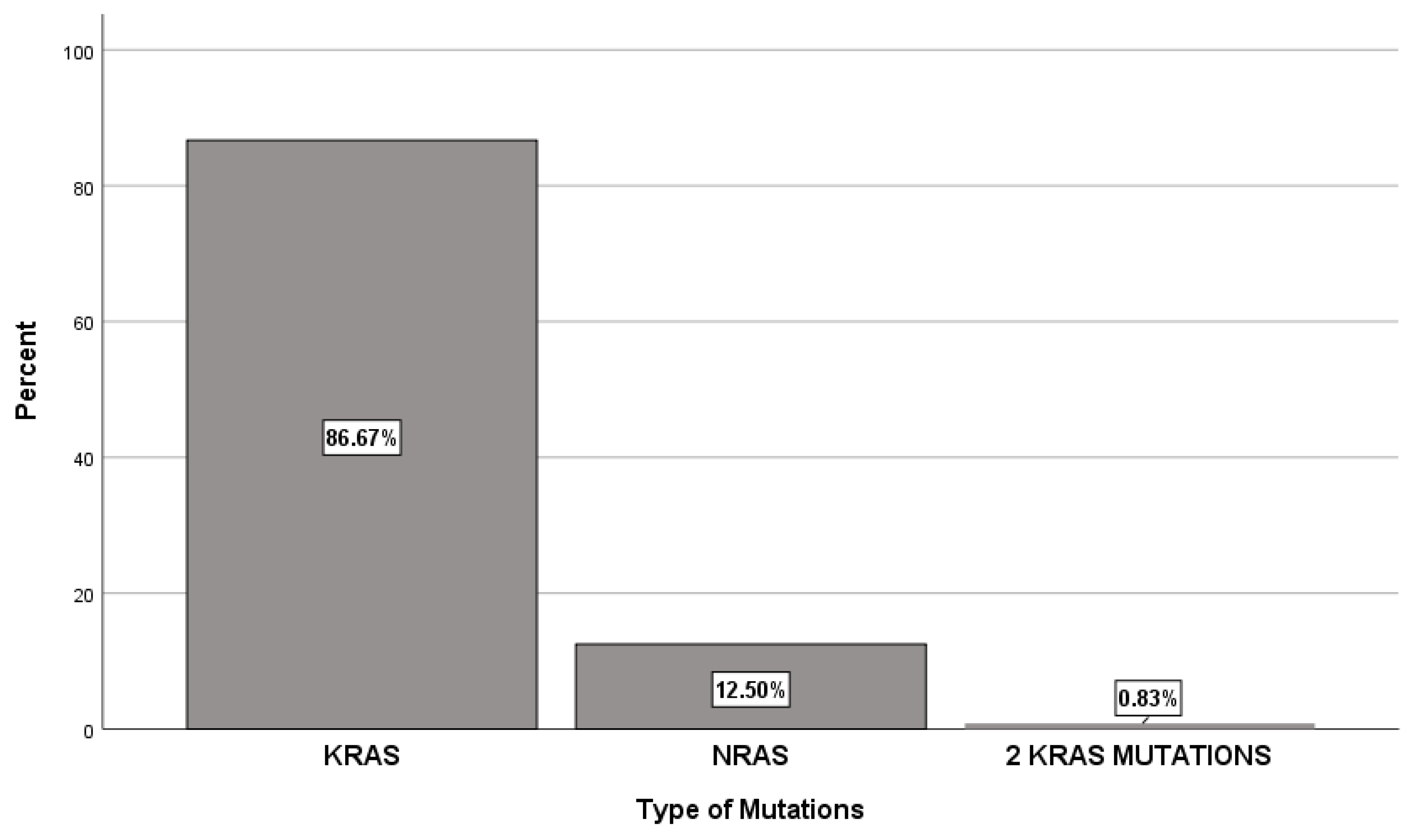

Among the 120 patients studied, the majority (86.7%) had KRAS mutations, whereas NRAS mutations were identified in only 12.5% from the cases. Additionally, one patient exhibited two KRAS mutations (

Figure 1). The most common KRAS activating mutation was c.35G>A (Gly12Asp), observed in 29.2% of cases and exon 2 was the most affected, in 75% of cases (

Table 2 and

Table 3). For the NRAS gene, the c.181C>A (Gln61Lys) mutation was observed in 3.3% of patients with exon 3 being the most commonly affected in 6.7% of cases (

Table 2 and

Table 3). As for gender distribution, KRAS mutations were more prevalent in males (59.2%) compared to females (27.5%). In contrast NRAS mutations showed a nearly equal gender distribution, with 6.7% male and 5.8% female (

Table 4). KRAS mutations were most frequently observed in the 71–80 age group, while NRAS mutations were most common in the 61–70 age group. Rectal cancer was the most prevalent tumor location associated with KRAS mutations in 34.17% and NRAS mutations in 8.3%. Stage IV disease was the most prevalent, occurring in 52.6% of patients with KRAS mutations and 10% of those with NRAS mutations. Moderately differentiated (G2) tumors were the most common, accounting for 69.2% of cases in patients with KRAS mutations and 10.8% in patients with NRAS mutations (

Table 4).

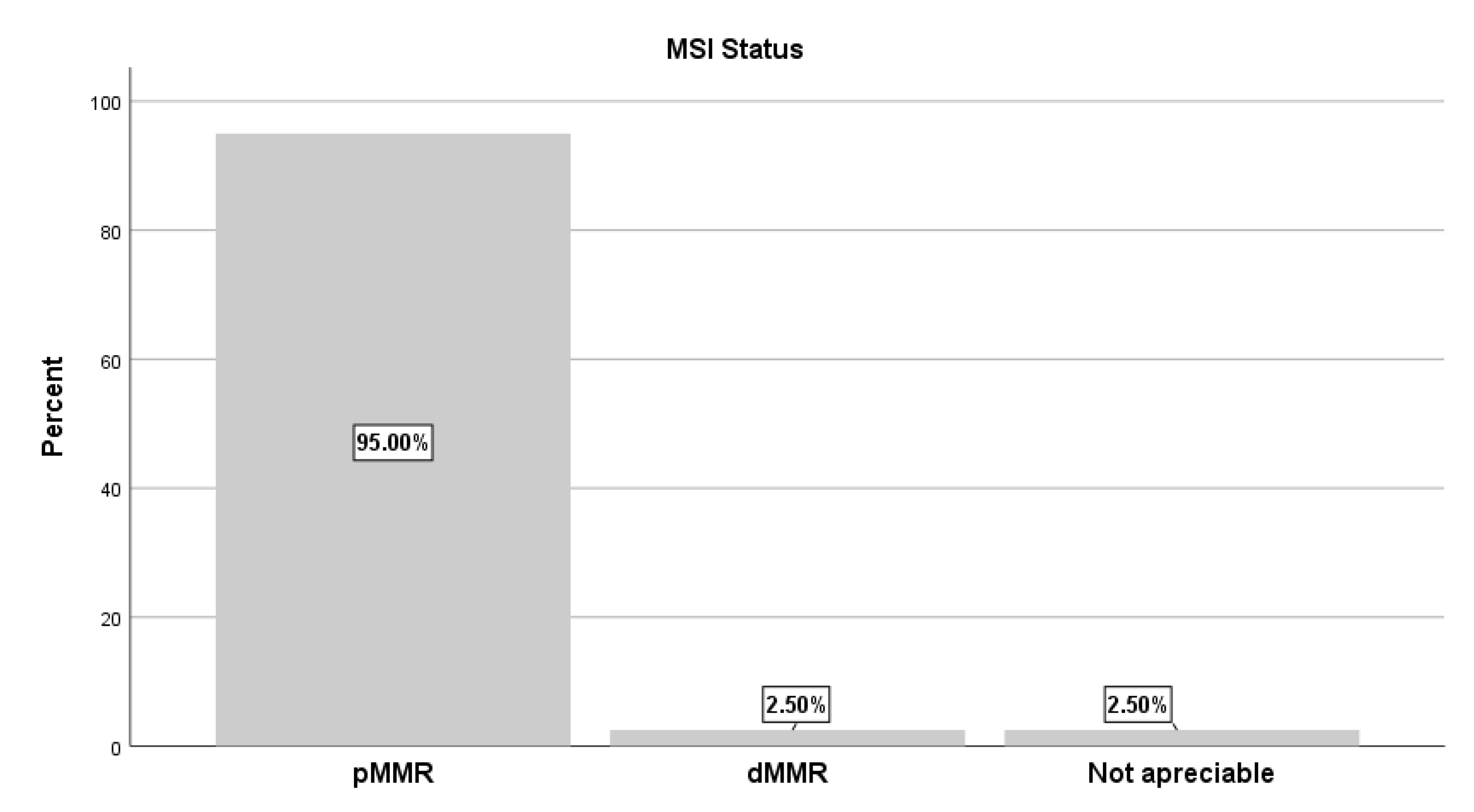

Regarding MMR/MSI status, pMMR/MSS was observed in 95% of all cases, coexisting with KRAS or NRAS mutations. In contrast, only 2.5% exhibited dMMR/MSI-H, while in another 2.5% MSI status could not be determined (

Table 4). Among patients with MSS status, male patients accounted for 62.5% compared to 32.5% for female patients. The 71–80 age group had the highest incidence, (

Table 4). Regarding tumor localization, rectal tumors were most frequently associated with stable MSI status, identified in more than one-third of all cases. At the time of MSS assessment, the disease was predominantly stage IV, followed by stage III. Moderately differentiated tumors were the most commonly observed 75.8% (

Table 4).

For deficient MMR/MSI-H status, all cases were observed in male patients (2.5%). Regarding age distribution, the majority (1.7%) were in the 51–60-year age group (

Table 4). In terms of tumor localization, one case each was identified in the right colon, left colon, and with an occult primary site. All dMMR/MSI-H cases were diagnosed in stage IV (2.5%) and all tumors were moderately differentiated (G2, 2.5%) (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Colorectal cancer is a heterogeneous oncological pathology, with a very high distribution among population in our country as well as worldwide. The diverse mechanisms underlying the disease’s development, particularly genetic alterations, have led to the identification of biomarkers with diagnostic and prognostic significance, including KRAS, NRAS mutations and MSI status [

18,

27,

28,

29].

All 262 patients included in our study were diagnosed by the pathologists with adenocarcinoma. Of these, 39.7% patients had KRAS mutation, 5.7% of patients had NRAS mutations and 0.4% had a dual KRAS mutation. Comparing our findings to the specialized literature shows agreement regarding the proportion of KRAS and NRAS mutations. KRAS mutations are reported in 35–45% of colorectal cancer cases, while NRAS mutations occur in 1–6% of cases [

6,

17,

19,

27,

29,

30]. Of the 262 patients, 251 individuals (95.8%) exhibited an MSI-stable/MSS/pMMR status and deficient MMR status was identified in 11 individuals (4.2%). This prevalence is notably lower compared to data reported in the literature, where deficient MMR occurs more frequently, especially in European population (5–24%), Caucasian Americans of European descent (8–20%), African Americans (12–45%), and Egyptians (37%). In contrast, populations from Asian countries, particularly China and Japan, show lower incidence rates, ranging from 3.8% to 10% [

18,

29,

31,

32]. Considering the dMMR/MSS distribution among our patients, we observed a notably lower incidence compared to other European countries. However, it remains relatively similar to the incidence reported in Asian populations. This suggests significant ethnic diversity and genetic variability within our population, influenced by lifestyle and dietary factors. Additionally, variations in detection methodologies, including equipment and technical protocols, may contribute to differences in determining MMR status.

This research is the first of its kind in Romania to examine the association between the morphopathological characteristics of colorectal cancers and KRAS or NRAS mutations, in combination with MSI status.

4.1. Colorectal Cancer and KRAS Mutation

Regarding the activating mutation within the KRAS gene, the most frequently observed variant was c.35G>A (Gly12Asp), identified in 29.2%, followed by c.38G>A (Gly13Asp), detected in 17.5%. Both mutations were located within exon 2. These findings are consistent with the data reported in the literature, where studies from both European and Asian populations have confirmed the same mutation localization [

6,

29,

31,

33]. This consistency suggests that the global distribution of populations does not significantly influence this characteristic.

Our research revealed a clear male predominance among colorectal cancers with KRAS mutations, with 59.2% of cases in males compared to 27.5% in females. This aligns with the well-established observation that colorectal cancer incidence is higher in males [

1,

5,

8].

While colorectal cancer is known to be more prevalent after the age of 50, with many studies across Europe, Asia, and even Africa reporting a median age of onset around 65 years, our study noted an older age distribution [

18,

29,

31,

34,

35]. The largest group of patients (29.2%) was in the 71–80 year age range, followed closely by the 61–70 year group, which represented 25.8% of patients.

When analyzing tumor localization, our findings revealed a higher prevalence of rectal cancers associated with KRAS mutations, compared to left-sided colon cancers and right-sided colon cancers. Existing studies show variability. For example, Kawazoe et al. reported a notable association between KRAS mutations and rectal cancers, El Agy et al. documented KRAS mutations in left-sided colon cancers, while Zhang et al. highlighted their presence in right-sided colon cancers [

36,

37,

38]. These findings reflect the heterogeneous nature of KRAS-associated colorectal cancer localization patterns.

More than a half of all patients included in this study were identified with stage IV adenocarcinoma. Previous studies have not demonstrated a statistically significant correlation, only one study did highlight that older patients are more frequently diagnosed with stage IV [

18].

Moderately differentiated colorectal cancer (G2) was the most frequently observed tumor grade in our study population (69.2%). While many studies have not shown a statistically significant correlation, Bisht et al. found that G2 tumors are associated with KRAS mutation [

27].

4.2. Colorectal Cancer and NRAS Mutation

Mutations in the NRAS gene are extremely rare, and limited data are available in the scientific literature [

34,

38,

39,

40,

41]. In our study, the most frequent activating mutation identified was c.181C>A Gln61Lys in exon 3, observed in 3.3% of patients. While the study conducted by Jauhri et al. noted a higher prevalence of this mutation in females, our cohort showed minimal difference between the sexes, with males slightly more affected (6.7%) compared to females (5.8%) [

41].

Our study reveals that the most of the malignancies occurred in the colorectal region, with NRAS mutation observed in 8.3% of rectal cancers, 2.5% in left colon cancers, and 1.7% in right colon cancers. The findings from Jauhri et al. report a similar distribution of NRAS mutations across tumor sites, with the activating mutation located at codon 61 (41).

The majority of patients with NRAS mutation in our study were in 61–70 age group, (6.7%), followed by 71–80 age group, (5%.) This suggests that NRAS mutations may occur at an earlier age compared to KRAS mutations.

4.3. Colorectal Cancer with KRAS or NRAS Mutation and MSI Status

Regarding MSI status associated with either KRAS or NRAS mutations, our cohort included 43.5% of patients with MSS/pMMR, 1.15% of patients with dMMR/MSI-H , and 1.15% of patients with an uninterpretable MSI/MMR status. All patients were diagnosed by the pathologists with colorectal adenocarcinoma.

Age distribution among patients with MSI-S status showed that the majority were in the 71–80 years age group (33.3%,) followed by 61–70 years age group, (30.8%). In contrast, the MSI-H mutations were observed most frequently in 51–60-year age group (7%). Only 0.8% of cases exhibited this MSI-H status in the 61–70-year age group. The study conducted by Wang et al. found a higher incidence of MSI-H in younger patients compared to those with MSS, while Niu et al. reported a higher prevalence of MSI-H in older patients, though their analysis which was limited to individuals with stage III colorectal cancer [

22,

42].

In our analysis, we identified that among patients with pMMR status, almost two-thirds (

62.5%) were male and less than one third females. Conversely, alterations in dMMR status were observed exclusively in male patients, represent 2.5%. Existing studies have generally reported a higher incidence of dMMR status among female patients, regardless of geographic region, including studies conducted in Africa and Asia, though statistical significance has not always been demonstrated [

18,

22,

42]. Furthermore, there is limited information in the literature regarding the relationship between KRAS mutations and dMMR status in colorectal cancer.

Regarding the localization of colorectal tumors with KRAS or NRAS mutations and MSI status, a significant proportion were identified as rectal cancers, (41.62%), followed by right-sided colon cancers (26.6%), left-sided colon cancers (24.98%), and occult tumors among patients with MSS (1.66%). In contrast, among patients with MSI-H status, right-sided colon cancer, left-sided colon cancer, and occult tumors were each observed in equal percentages (0.8%), with no cases of rectal cancer reported. The significant statistical result (p = 0.015), suggests a potential predisposition for rectal cancers with KRAS or NRAS mutations in the context of MSS status. Our findings indicate that MSI-H status is more frequently associated with colon tumors. However, studies examining the coexistence of KRAS or NRAS mutations with MSI status in colorectal cancer remain limited. Available evidence suggests that MSI-H status is predominantly associated with right-sided colon cancers, while MSS is more prevalent in left-sided colon and rectal cancers as observed in the study by Niu et al [

22]. Moreover, Kaseem et al. identified three cases of rectal cancer with KRAS mutations and MSI-H status in their investigation of the Egyptian population, although these findings did not reach statistical significance [

18].

The majority of cases in our MSI-H group were diagnosed with stage IV (59.2%), followed by stage III (32.5%) and stage II (3.3%) All cases in the MSI-H group were classified as stage IV disease. These findings align with existing literature, which suggests that MSI-H status is correlate with advanced stages of the disease [

18,

42,

43]. However, it is important to note that the number of MSI-H patients included in our study is relatively small, limiting these observations. Nonetheless, research conducted by Formica et al. highlights the increased aggressiveness of tumors with MSI-H status, which can be observed from early-stage disease to advanced metastatic progression [

40,

44].

Although literature often correlates MSI-H status with poorly differentiated tumor grading, all cases in our cohort were classified as moderately differentiated (G2). Similarly, most MSS tumors were also moderately differentiated, representing 75.8% of cases [

22].

Giving the high frequency of KRAS mutations and the substantial number of MSS cases, we evaluated the potential statistical relevance between these two factors. Our statistical analysis yielded a significant result (p=0.0001). Despite this, studies supporting this association remain scarce and typically lack statistical significance [

18,

45]. A meta-analysis by Ashktorab et al., showed a higher incidence of colorectal cancers with MSS status and KRAS mutation in the African-American population compared to the Caucasian population [

43]. However, other investigations suggest that the combination of KRAS mutations and MSS status is linked to greater tumor aggressiveness, poorer prognosis, and lower overall survival rates compared to MSS tumors without KRAS mutations [

30,

44,

46,

47]. This observation supports the hypothesis that KRAS mutations in conjunction with pMMR/MSS status may represent a distinct molecular subtype of colorectal cancer with unique clinical and pathological features [

30]. In their study, Li et al. demonstrated that KRAS activation plays a key role in tumor cell invasion and metastasis in pMMR/MSS tumors [

48].

The limitations of our study include the inability to track the prognosis and survival outcomes of patients from various hospitals, cities, counties, and regions across the country. Additionally, another limitation is the relatively small number of colorectal cancer cases with KRAS or NRAS mutations in association with MSI-H status.

5. Conclusions

Our study, the only one conducted in Romania and among the few globally, provides a comprehensive analysis of the association between rectal malignancies and the presence of KRAS mutations alongside pMMR/MSS status. This finding supports the hypothesis that KRAS mutations, in combination with pMMR status, may define a distinct molecular subtype of colorectal cancer with unique clinical and pathological characteristics. Further research into the relationship between KRAS mutations and pMMR status is essential to better understand its potential impact on tumor biology, therapeutic response, and survival outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization O.P, R.A and O.B.; methodology, R.A, L.A; formal analysis, A.C and O. C writing—original draft preparation, R.A, L.A, A.C., O.C.; writing—review and editing, O.B., O.P.; supervision, O.P., O.B.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Oradea, Oradea, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Resident Laboratory (nr. 11/20.12.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

The study was retrospective, used archived material, and required no further procedures.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study can be made available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MAPK |

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| mTOR |

Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| CpG |

Cytosine-phosphate-guanine |

EGFR

KRAS |

Epidermal growth factor receptor

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| NRAS |

Neuroblastoma rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| MMR |

Mismatch repair |

| MSI |

Microsatellite instability |

| MSI-H |

Microsatellite Instability-High |

| MSI-L |

Microsatellite Instability-Low |

| MSS |

Microsatellite Stable |

| dMMR |

Deficient mismatch repair |

| pMMR |

Proficient mismatch repair |

| CRC |

Colorectal cancer |

| |

|

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/colorectal-cancer (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Cancer-plan.ro. Available online: https://cancer-plan.ro/copac-cancerul-colorectal-peste-13-din-totalul-cancerelor-in-romania/ (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- NCCN Colon Cancer Colon Cancer. NCCN Harmon. Guidel. Sub-Saharan Africa - Colon Cancer 2018, Version 2., 1–5.

- Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Roselló, S.; Arnold, D.; Normanno, N.; Taïeb, J.; Seligmann, J.; De Baere, T.; Osterlund, P.; Yoshino, T.; et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up ☆. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GLOBOCAN. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/41-colorectum-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Brinzan, C.S.; Aschie, M.; Cozaru, G.C.; Deacu, M.; Dumitru, E.; Burlacu, I.; Mitroi, A. KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and AKT1 signatures in colorectal cancer patients in south-eastern Romania. Med. (United States) 2022, 101, E30979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argilés, G.; Tabernero, J.; Labianca, R.; Hochhauser, D.; Salazar, R.; Iveson, T.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Quirke, P.; Yoshino, T.; Taieb, J.; et al. Localised colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshandel, G.; Ghasemi-Kebria, F.; Malekzadeh, R. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/cancer-statistics/colorectal-cancer-statistics/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Abrudan, R.; Abrudan, L.; Pop, O.; Zaha, D.C. A Rare Case of an Occult Primary Tumor With a Profile of Colon Cancer and Synchronous Metastasis in the Lung, Liver, Bone, and Cerebellum: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2023, 15, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufill, J.A. Colorectal cancer: Evidence for distinct genetic categories based on proximal or distal tumor location. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990, 113, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Cho, M.S.; Kim, N.K. Difference between right-sided and left-sided colorectal cancers: from embryology to molecular subtype. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2018, 18, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papilian, Victor, prof univ dr Ion Albu, prof univ. dr. A.V. Anatomia omului Vol II Splanhnologia, 12th ed.; ALL: București, 2010.

- Sawicki, T.; Ruszkowska, M.; Danielewicz, A. Factors, Development, Symptoms and Diagnosis. Mdpi 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Benedix, F.; Kube, R.; Meyer, F.; Schmidt, U.; Gastinger, I.; Lippert, H. Comparison of 17,641 patients with right- and left-sided colon cancer: Differences in epidemiology, perioperative course, histology, and survival. Dis. Colon Rectum 2010, 53, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccini, A.; Marshall, J.L.; Salem, M.E. Molecular Variances Between Right- and Left-sided Colon Cancers. Curr. Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2018, 14, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, E.; Kuzu, M.A.; Öztuna, D.; Işik, Ö.; Canda, A.E.; Balik, E.; Erkasap, S.; Yoldaş, T.; Akyol, C.; Demirbaş, S.; et al. Fall of another myth for colon cancer: Duration of symptoms does not differ between right- or left-sided colon cancers. Turkish J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 30, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökmen, İ.; Taştekin, E.; Demir, N.; Özcan, E.; Akgül, F.; Hacıoğlu, M.B.; Erdoğan, B.; Topaloğlu, S.; Çiçin, İ. Molecular Pattern and Clinical Implications of KRAS/NRAS and BRAF Mutations in Colorectal Cancer. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 7803–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, N.M.; Emera, G.; Kassem, H.A.; Medhat, N.; Nagdy, B.; Tareq, M.; Moneim, R.A.; Abdulla, M.; El Metenawy, W.H. Clinicopathological features of Egyptian colorectal cancer patients regarding somatic genetic mutations especially in KRAS gene and microsatellite instability status: a pilot study. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Fan, W.; Li, J.; Wu, G.; Wu, H. KRAS/NRAS Mutations Associated with Distant Metastasis and BRAF/PIK3CA Mutations Associated with Poor Tumor Differentiation in Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, Volume 16, 4109–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, D. Mutation patterns and prognostic analysis of BRAF / KRAS / PIK3CA in colorectal cancer. 2022, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Mulet-margalef, N.; Linares, J.; Badia-ramentol, J.; Jimeno, M.; Monte, C.S.; Manzano, L.; Calon, A. dMMR / MSI-H Colorectal Cancer Landscape. 2023, 1–17.

- Niu, W.; Wang, G.; Feng, J.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Shan, B. Correlation between microsatellite instability and RAS gene mutation and stage III colorectal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demes, M.; Scheil-Bertram, S.; Bartsch, H.; Fisseler-Eckhoff, A. Signature of microsatellite instability, KRAS and BRAF gene mutations in German patients with locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma before and after neoadjuvant 5-FU radiochemotherapy. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2013, 4, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.X.; Su, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Du, Y.Y.; Gao, Y.J.; Li, W.L.; Hu, W.Q.; Zhao, J. Oncological characteristics, treatments and prognostic outcomes in MMR-deficient colorectal cancer. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, A.; Pedraza, R.; Kennecke, H. Developments in Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy for the Management of Deficient Mismatch Repair (dMMR) Rectal Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 3672–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimrat Khehra; Inderbir S. Padda; Cathi J. Swift. Polymerase chain reaction. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589663/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Bisht, S.; Ahmad, F.; Sawaimoon, S.; Bhatia, S.; Das, B.R. Molecular spectrum of KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA gene mutation: determination of frequency, distribution pattern in Indian colorectal carcinoma. Med. Oncol. 2014, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizee, M.I.; Talib, N.L.A.; Hamdan, A.H.B.; Abdullah, N.Z.B.; Rahimi, B.A.; Haidary, A.M.; Saadaat, R.; Hanifi, A.N. Concordance between immunohistochemistry and MSI analysis for detection of MMR/MSI status in colorectal cancer patients. Diagnostic Pathol. 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S.Y.; Tan, L.X.; Liu, X.Z.; Yang, L.J.; Li, N.N.; Feng, Q.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, D.B.; Zhou, L.X.; et al. KRAS, NRAS, BRAF signatures, and MMR status in colorectal cancer patients in North China. Med. (United States) 2023, 102, E33115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Yan, W.Y.; Xie, L.; Lei, C.; Mi, Y.; Li, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, B.R.; Qian, X.P. Coexistence of MSI with KRAS mutation is associated with worse prognosis in colorectal cancer. Med. (United States) 2016, 95, e5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sougklakos, I.; Athanasiadis, E.; Boukovinas, I.; Karamouzis, M.; Koutras, A.; Papakotoulas, P.; Latsou, D.; Hatzikou, M.; Stamuli, E.; Balasopoulos, A.; et al. Treatment pathways and associated costs of metastatic colorectal cancer in Greece. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2022, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Ding, H.; Sun, S.; Luan, Z.; Liu, G.; Li, Z. Incidence and detection of high microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer in a Chinese population: A meta-analysis. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2020, 11, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Li, B.T.; O’Reilly, E.M. Targeting KRAS in cancer. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 969–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaferi, Z.; Pirestani, M.; Arefian, E.; Gojani, G.; Kavousinasab, N.; Karimi, P.; Deilami, A.; Abrehdari-Tafreshi, Z. Exploring the Relationship Between KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF Mutations and Clinical Characteristics in Iranian Colorectal Cancer Patients. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2024, 55, 1134–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.L.; Li, Q.X.; Ma, Z.P.; Shi, Y.; Ma, Y.Q.; Li, X.X.; Cui, W.L.; Zhang, W. Association between clinicopathological fessociationtures and survival in patients with primary and paired metastatic colorectal cancer and KRAS mutation. Onco. Targets. Ther. 2017, 10, 2645–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agy, F. El; Bardai, S. el; Otmani, I. El; Benbrahim, Z.; Karim, I.M.H.; Mazaz, K.; Benjelloun, E.B.; Ousadden, A.; Abkari, M. El; Ibrahimi, S.A.; et al. Mutation status and prognostic value of KRAS and NRAS mutations in Moroccan colon cancer patients: A first report. PLoS One 2021, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawazoe, A.; Shitara, K.; Fukuoka, S.; Kuboki, Y.; Bando, H.; Okamoto, W.; Kojima, T.; Fuse, N.; Yamanaka, T.; Doi, T.; et al. A retrospective observational study of clinicopathological features of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in Japanese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, J.; Yang, Y.; Lu, J.; Gao, J.; Lu, T.; Sun, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Molecular spectrum of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in Chinese colorectal cancer patients: Analysis of 1,110 cases. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negru, S.; Papadopoulou, E.; Apessos, A.; Stanculeanu, D.L.; Ciuleanu, E.; Volovat, C.; Croitoru, A.; Kakolyris, S.; Aravantinos, G.; Ziras, N.; et al. KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutations in Greek and Romanian patients with colorectal cancer: A cohort study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlandi, E.; Giuffrida, M.; Trubini, S.; Luzietti, E.; Ambroggi, M.; Anselmi, E.; Capelli, P.; Romboli, A. Unraveling the Interplay of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and Micro-Satellite Instability in Non-Metastatic Colon Cancer: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauhri, M.; Bhatnagar, A.; Gupta, S.; Manasa, B.P.; Minhas, S.; Shokeen, Y.; Aggarwal, S. Prevalence and coexistence of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, NRAS, TP53, and APC mutations in Indian colorectal cancer patients: Next-generation sequencing–based cohort study. Tumor Biol. 2017, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, R.; Han, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, L.; Gu, Y. Epidemiological and clinicopathological features of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF mutations and MSI in Chinese patients with stage I-III colorectal cancer. Med. (United States) 2024, 103, E37693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashktorab, H.; Ahuja, S.; Kannan, L.; Llor, X.; Nathan, E.; Xicola, R.M.; Laiyemo, A.O.; Carethers, J.M.; Brim, H.; Nouraie, M. A meta-analysis of MSI frequency and race in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 34546–34557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, V.; Sera, F.; Cremolini, C.; Riondino, S.; Morelli, C.; Arkenau, H.T.; Roselli, M. KRAS and BRAF Mutations in Stage II and III Colon Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Lin, J.K.; Lin, T.C.; Chen, W.S.; Yang, S.H.; Wang, H.S.; Lan, Y.T.; Jiang, J.K.; Yang, M.H.; Chang, S.C. The prognostic role of microsatellite instability, codon-specific KRAS, and BRAF mutations in colon cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 110, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cuba, E.M.V.; Snaebjornsson, P.; Heideman, D.A.M.; Van Grieken, N.C.T.; Bosch, L.J.W.; Fijneman, R.J.A.; Belt, E.; Bril, H.; Stockmann, H.B.A.C.; Hooijberg, E.; et al. Prognostic value of BRAF and KRAS mutation status in stage II and III microsatellite instable colon cancers. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, J.; Cecchini, M.; Sheth, A.; Stein, S.; Lacy, J.; Kim, H.S. Microsatellite instability and KRAS mutation in stage IV colorectal cancer: Prevalence, geographic discrepancies, and outcomes fromthenational cancer database. JNCCN J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhi, W.; Zou, S.; Qiu, T.; Ling, Y.; Shan, L.; Shi, S.; Ying, J. Distinct clinicopathological patterns of mismatch repair status in colorectal cancer stratified by KRAS mutations. PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).