1. Introduction

The global burden of colorectal cancer (CRC) was estimated at over 1.9 million new cases (9.6 % of total, rank 3) and over 900 000 deaths (9.6 of total, rank 2) in 2022 making it one of the most prominent cancer diseases [

1]. Projections of increase up to 3.2 million new cases and 1.6 million deaths by 2040 [

2] highlight the necessity for prevention strategies of affecting modifiable risk factors, coupled with early detection and adequate follow up of premalignant lesions are constantly being highlighted, though with limited success. The preventive effect of screening colonoscopy is likely much stronger, and manifests much earlier than recently reported. With increasing annual incidence (1.7%) and mortality (0.5%) rates of colon, rectum and anus cancers in the young adults’ population (15-49 years of age) urge more efficient approaches and spread of health equity plans [

3].

In Serbia, the morbidity and mortality induced by colorectal, lung, stomach, breast and cervical cancers had a major impact on the population in an analyzed 5-year period (1999–2003), inducing 73,197 (19.9/1,000 population) disability adjusted life years (DALYs) in men and 60,482 (15.6/1,000) DALYs in women, annually [

4]. Analysis of trends in the cancer burden in the Balkan region in the period 1990-2019, have shown that years of life lost (YLL) rates due to CRC are forecasted to increase by 2030 [

5]. Described country-specific barriers are mostly related to lifestyles and low uptake of screening and early detection, as well as availability of treatment options. Most expenses due to CRC pertain to advance stage disease inpatient care, targeted therapies, diagnostic imaging and invasive radiology procedures [

6]. Although in line with the rise in CRC incidence, the total cost of accompanying medical services is even higher (27% increase in the period 2014 to 2017).

The aim of this study was to provide an overview of the progress in personalized medicine of CRC in Serbia, with results and insights from the Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia (IORS), the National Cancer Research Center, and to propose guidance for tackling observed challenges in the future.

2. Material and Methods

Epidemiological data was derived from official global and national cancer registries. Annual patient numbers treated at IORS were derived from electronic medical records. Diagnostic analyses were conducted using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples (FFPE), extracting DNA using either the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Manchester, UK) or the Cobas

® DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). RAS mutation detection was conducted using various in vitro diagnostics (IVD)-registered methods, including the KRAS StripAssay, TheraScreen

® K-RAS Mutation Kit on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR, TheraScreen

® KRAS RGQ PCR Kit on the Qiagen Rotor Gene Q, Cobas

® KRAS Mutation Test on the Cobas

® 4800, and AmoyDx KRAS/NRAS Mutation Detection Kit on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR or LightCycler

® 480 Instrument II. Graphical schemes were reported according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [

7].

All clinical, molecular testing and research analyses have been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia. All experiments have been performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology and Risk Factors in Serbia

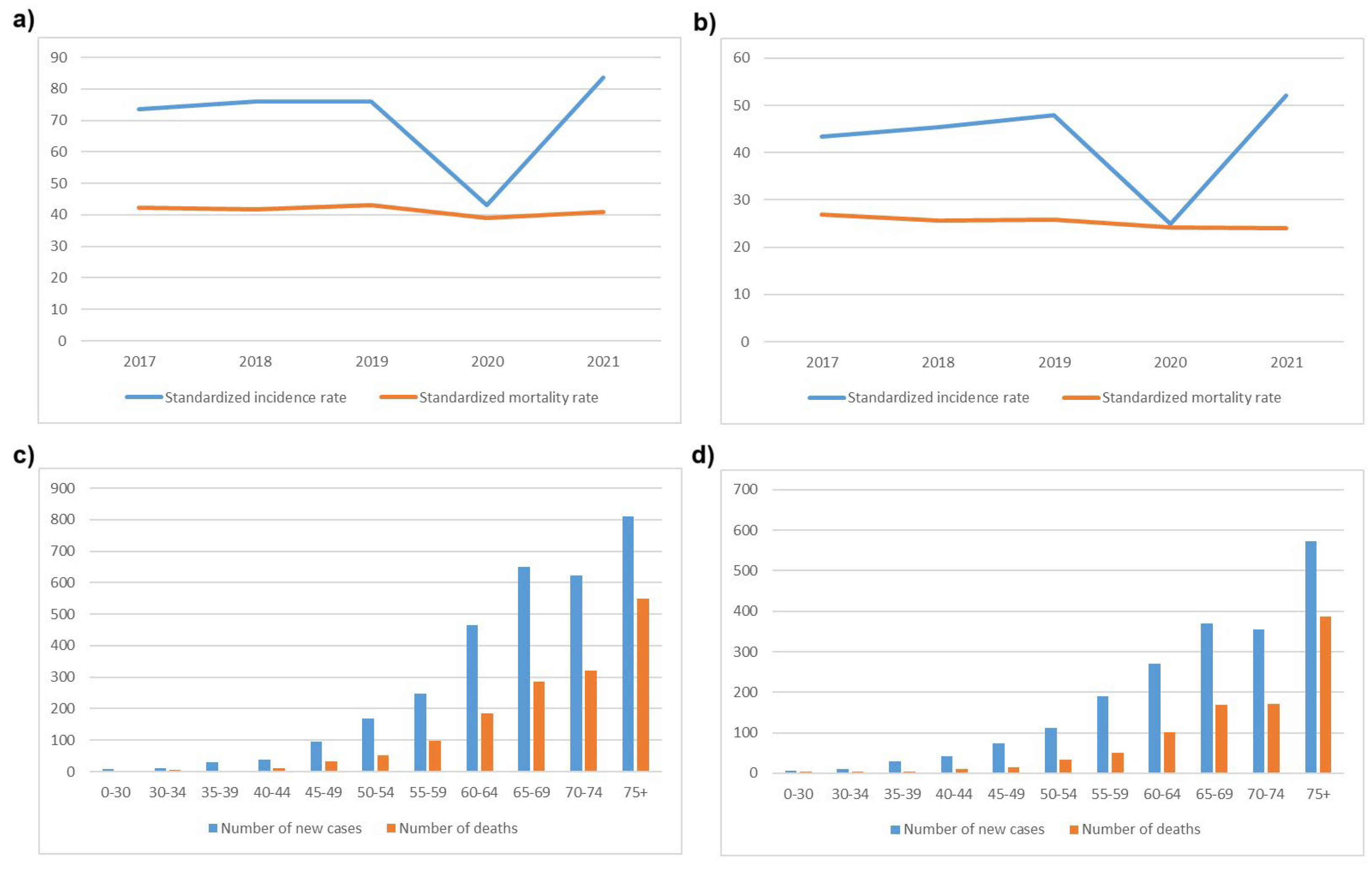

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the major public health problems in Serbia. The standardized incidence rates CRC in central Serbia have been steadily increasing, by about 0.7% per year for females and 1% per year for males in the period between 1999-2020 [

8]. According to official data from the Serbian Cancer Registry of the Institute of Public Health of Serbia “Dr Milan Jovanović Batut” in 2021, CRC was newly diagnosed in 5174 patients (2029 females, 3145 males), comprising 12.4% of all cancers, making it the second most common cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality [

9]. CRC was the second most common cancer among males (14.1 %) after lung cancer, and the third most common cancer among females (10.5%), after breast and lung cancer. Standardized incidence and mortality rates, and the number of new cases in males and females per age group in a 5-year period (2017-2021) according to official data from the Serbian Cancer Registry are presented in

Figure 1. As in other countries, incidence of young-onset CRC has been increasing over the past 10 years [

10].

In general, risk factors for CRC are divided into modifiable and non-modifiable. Modifiable risk factors are mostly connected to lifestyle, such as smoking, alcohol abuse, diet high in fat and processed foods and low in fiber, obesity, sedentary lifestyle. Non-modifiable risk factors are age, race, sex at birth, personal history of colorectal polyps or cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, personal history of irradiation of abdomen or pelvis, family history of adenomatous polyps and CRC and certain genetic syndromes [

11]. In Serbia, the combined effect of red-meat based diet and a high smoking rate have been suggested as predominant CRC risk factors although a relevant population-based study with high statistical power has not been performed.

3.2. Screening, Prevention and Early Detection Programs

Primary (avoiding risk factors and promoting protective factors) and secondary prevention (screening) of CRC have been proven to decrease CRC incidence and mortality. Organized CRC screening was implemented in Serbia in December of 2012. All individuals over the age of 50 are offered fecal occult blood test, and those with a positive finding are referred to colonoscopy. The program is carried out through the primary care physicians initially and if FOB test is positive, subjects are referred to secondary centers. The average participation rate was 52%, tests were positive in 7.2%, and out of those, 43.3% agreed to a colonoscopy. The positive predictive value was 27.1% for adenoma and 14.6% for carcinoma [

12].

3.3. Hereditary Risk Factors and Molecular Testing for Lynch Syndrome

Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC), is the most common hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, responsible for 2-3% of all CRC cases. This inherited condition significantly increases the risk of developing colorectal cancer as well as other cancers, including endometrial, ovarian, stomach, small intestine, liver, gallbladder ducts, upper urinary tract, brain, and skin cancers. The syndrome is caused by germline mutations in genes involved in DNA mismatch repair (MMR), specifically

MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and

EPCAM [

13,

14]. The risk of developing cancer varies based on both the specific gene mutation and gender. Individuals who carry mutations in the

MLH1 and

MSH2 genes have the highest penetrance, with a lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer estimated at around 50% by age 70. For those with

MSH6 and

PMS2 mutations, the risk is lower but still significant, particularly for

MSH6 carriers, who face a lifetime risk of about 30% by age 70. Additionally, the risk of endometrial cancer is notably high among carriers of MMR gene mutations, especially for those with

MLH1 and

MSH2 mutations, where the risk is estimated to be between 40-60% by age 70 [

15]. Recent studies underscore the need for colorectal cancer surveillance strategies tailored to the specific MMR gene mutations in Lynch syndrome patients. Intensive surveillance is advised for

MLH1 and

MSH2 mutation carriers, beginning at age 25 with 1-2 year intervals. However, for

MSH6 and

PMS2 carriers, starting later and extending the intervals between screenings may be more effective considering the balance between cost and timely tumor detection [

16]. According to guidelines from the European Hereditary Tumour Group (EHTG) and the European Society of Coloproctology (ESCP), the prevalence of pathogenic MMR gene carriers is estimated to be approximately one in 300, which equates to around 2.5 million people in Europe [

17].

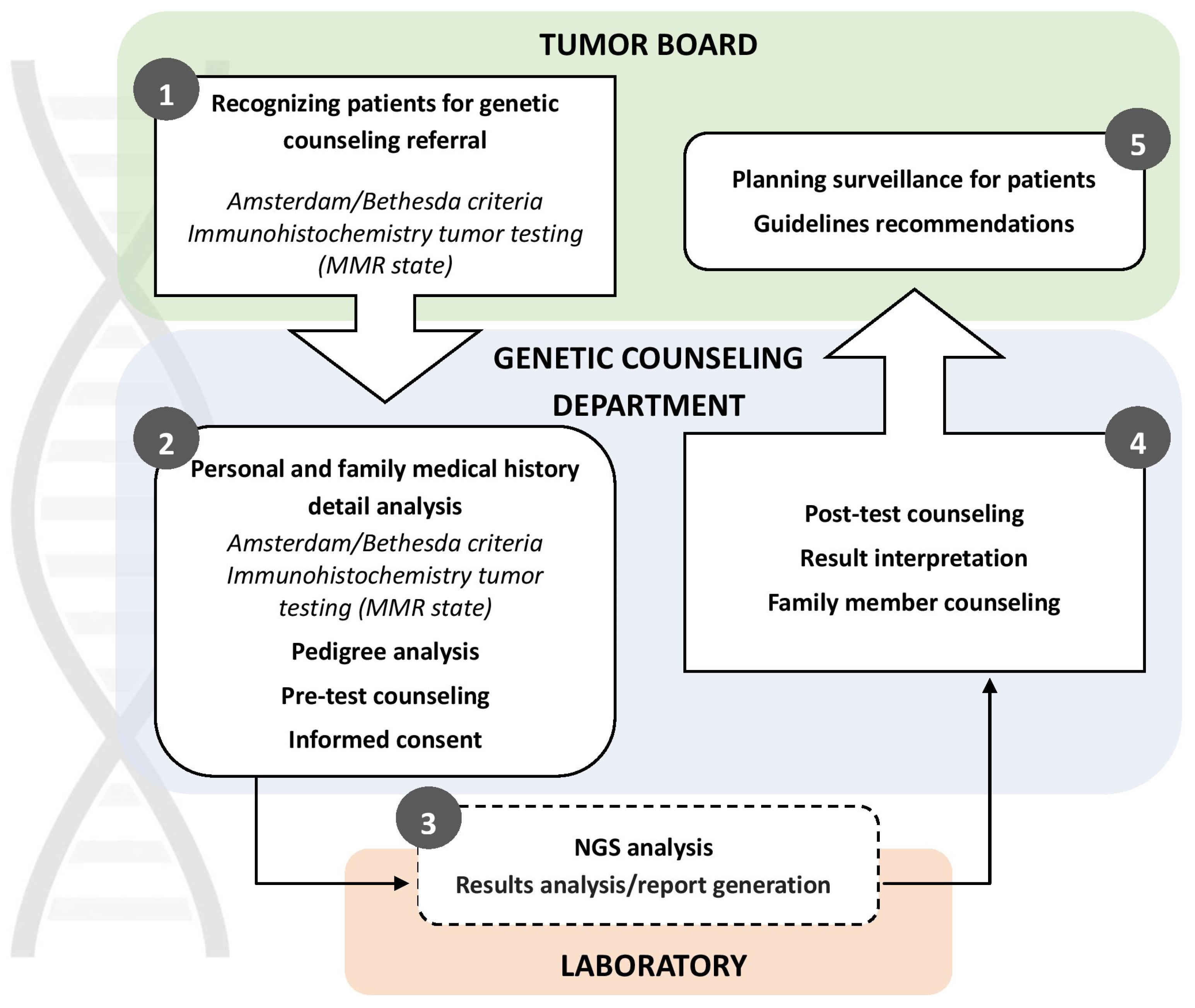

Since 2018, The Institute of Oncology and Radiology of Serbia has been conducting germline genetic testing for Lynch syndrome using Next Generation Sequencing technology (TruSight Cancer Panel, Ilumina). Patients are selected based on early-onset cancer and family history, following the Amsterdam Criteria and Bethesda Guidelines [

18]. In addition to indication of strong family history, patients are also referred for MMR germline genetic testing by tumor boards due to abnormal protein expression results identified through immunohistochemistry. Since the start of MMR germline genetic testing at IORS in 2018 through July 2024, a total of 122 individuals suspected of having HNPCC were referred to the Genetic Counseling for Hereditary Cancers Department at IORS by Serbian medical institutions. Of these, 113 met the Amsterdam/Bethesda criteria for Lynch syndrome testing, and 103 underwent testing so far. All participants provided informed consent for genetic testing, approved by the Ethics Board of IORS. NGS panel testing is funded by the Serbian Health Insurance Fund for patients who meet the criteria for genetic testing. At the time of this manuscript preparation, IORS was the only governmental institution in Serbia offering genetic counseling and testing for HNPCC.

During pre-test genetic counselling extensive personal and family histories (FH) were collected and mutation carrier probabilities (CP) were calculated using MMRpro (CaGENE 5.2 software (Cancer-Gene, Dallas, TX, available at

http://www4.utsouthwestern.edu/breasthealth/cagene), MMRPredict [

19], and PREMM [

20] prediction models. Those who did not meet the testing criteria included those with polyposis conditions, clinically diagnosed familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), or those assessed as having a very low risk of Lynch syndrome by the mentioned prediction models. Out of the 103 individuals tested, 19 (18.4%) were found to have a pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutation in one of the MMR genes. Pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations in other colorectal cancer-associated genes (

APC, CHEK2, MUTYH) were identified in 8 (7.8%) individuals, and variants of unknown significance (VUS) in genes associated with colorectal cancer (MMR genes

, APC, CHEK2) were detected in 8 (7.8%) individuals. 69 (67%) were wild type (WT) and had no genetic variants in the investigated panel. Regardless of the test results, all patients were invited for post-test genetic counselling at IORS, where further details regarding their families and potential additional testing were discussed. Afterward, patients were re-referred to their medical oncologist to discuss further treatment options (

Figure 2).

The introduction of germline MMR genetic testing at IORS represents a significant advancement in identifying individuals at risk for Lynch syndrome-associated cancers in Serbia. By implementing genetic testing and counseling services, healthcare professionals can provide personalized screening and preventive measures, potentially alleviating the burden of hereditary cancers within the population. This effort will also aid in identifying the frequency and spectrum of MMR gene mutations within this Slavic population, addressing the knowledge gap about the prevalence of Lynch syndrome genes in this part of Europe.

3.4. Diagnosis and Treatment

3.4.1. Diagnostic Considerations

Patients journey towards CRC diagnosis starts at a primary care level, which represents the first contact a person makes with health care providers (HCP) upon noticing symptoms. Here, a fecal blood test can be performed, and if positive, the patient is then referred to a secondary or tertiary center for further diagnostic procedures [

21,

22]. Overall, diagnostic capabilities in Serbia have improved, largely due to the widespread availability of endoscopic devices, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). However, the waiting time for radiologic procedures and colonoscopy is still more than 3 months in some areas, and pathology remains an issue, which in turn leads to an increase in the number of new diagnosis of CRC in advanced stages (~35% metastatic disease) [

10,

23]. The other problem is the low uptake of screening, which has been available in Serbia for the past ten years, as previously explained. There is still considerable room for improvement in the patient journey, as around half of patients experience at least a month-long delay to begin treatment [

24].

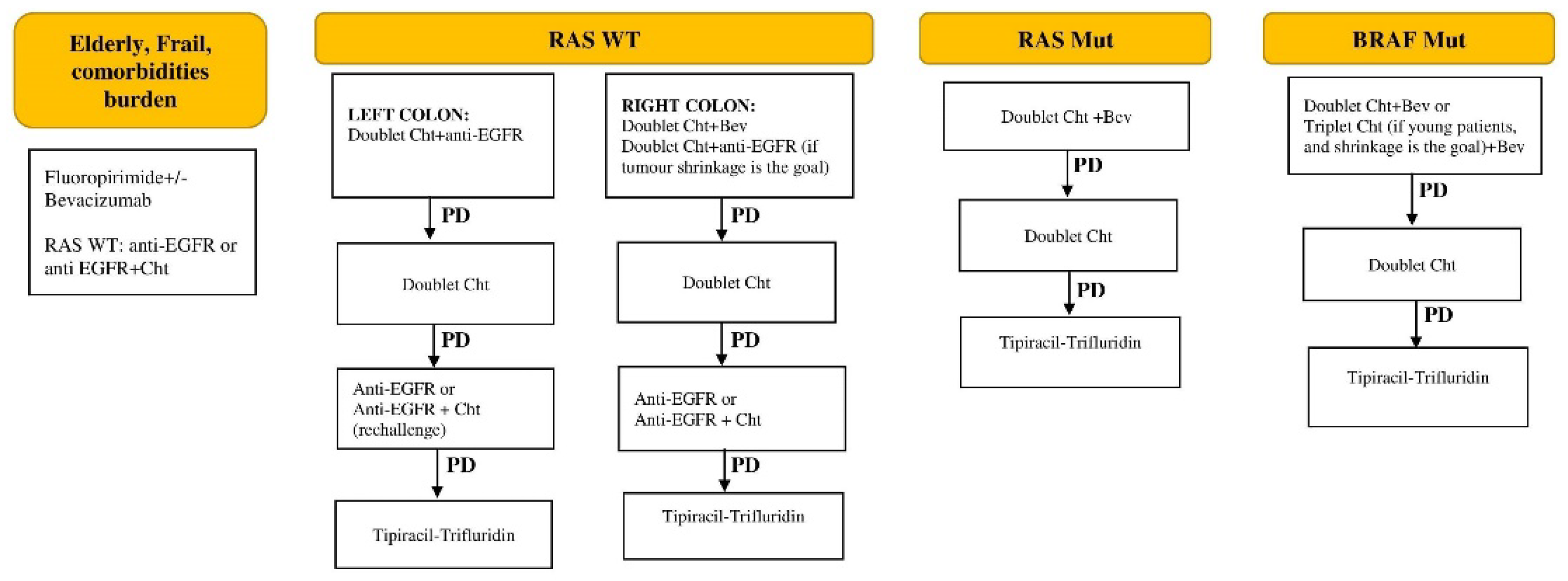

3.4.2. Systemic Therapy Approaches

The introduction of systemic therapies, including chemo, targeted, and immunotherapy, has significantly transformed the treatment landscape for advanced-stage CRC [

25]. In Serbia, systemic therapy is provided across 5 tertiary centers and around 40 general hospitals, for around 2000-3000 patients with metastatic CRC per year. At IORS, around 500 patients in various stages of disease are treated yearly. Systemic therapy has traditionally relied on doublet chemotherapy (Oxalipatin and Irinotecan-based), which were introduced in Serbia in the 2000s. Still, adjuvant use of oxaliplatin-based doublets wasn’t reimbursed until 2020. In systemic approach patient characteristics, sideness of the tumor and molecular profile are crucial factors in treatment decision-making process. The identification of RAS and BRAF mutations has become crucial in determining the most appropriate systemic treatments. Serbia is a country with long standing drug availability problems. Targeted therapies (Bevacizumab, Cetuximab, Panitumumab) became reimbursed as first-line treatments in 2022, after years of third-line and limited first-line use. By 2010, only 20% of patients received targeted therapy as a first-line treatment [

10]. Calculated 5-year overall survival in Serbian patients with CRC is going from 6.5% (95%CI) up to 14% in young-onset CRC (95%CI) [

10,

23].

The current management protocol of stage IV unresectable CRC in Serbia is presented in

Figure 3.

Progress in the availability of drugs has been slow, hindered by the limited list of reimbursed medications covered by health insurance. A recent addition is Tipiracil-Trifluridine, available from May 2024, for third-line and beyond treatment. Checkpoint inhibitors (CPI) are still not reimbursed for patients with MSI-high colorectal cancer, nor are other EMA and FDA-approved drugs (Regorafenib, Aflibercept, Encorafenib). On the other hand, an area that has seen significant improvement over the past two decades is supportive care, which is nowadays an integral part of treatment in Serbia, especially at IORS, and is offered upfront, during the active treatment and as end-of-life care.

3.4.3. Radiation Approaches

Radiotherapy plays an important role in the multidisciplinary treatment of colorectal cancer, particularly for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC). Since the establishment of the radiation oncology residency program in Serbia in 2011, significant progress has been made in training and educating professionals in this field. To further enhance the skills of radiotherapy technicians, a Master’s program for radiation therapists was introduced in 2022. Additionally, residency programs for medical physicists, established in 2013, have contributed to the overall improvement in the quality of radiotherapy services.

There are eight radiotherapy centers in Serbia equipped with modern linear accelerators (LINACs), employing three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT), volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT), intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), and respiratory gating. One center is equipped with a Gamma Knife for stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases. Image guidance, including cone-beam CT, is available across all centers for treatment delivery.

The Institute of Oncology and Radiology of Serbia has a long tradition in the treatment of LARC dating back to the early 1990s and was part of the EORTC 22921 study [

26], which laid the foundation for the introduction of the neoadjuvant approach in LARC treatment. Each year, approximately 150 patients with CRC undergo radiotherapy at IORS. Most CRC patients requiring radiotherapy have LARC and are treated with long course neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT). Modern treatment protocols in Serbia now involve precise disease staging through MRI as part of the initial evaluation process, as well as novel radiotherapy planning in accordance with international guidelines [

27]. Advanced radiotherapy techniques, such as VMAT and IMRT, are widely used. The typical radiotherapy doses range from 50.4 Gy to 54 Gy, applied using either sequential or simultaneous boost techniques in a long-course regimen.

For high-risk patients (clinical T4a/T4b stage, presence of extramural vascular invasion (EMVI), clinical N2 stage, involved circumferential resection margin (CRM), or enlarged lateral lymph nodes), total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT) is often employed. Additional cycles of chemotherapy may be administered before CRT (induction approach) or between the completion of CRT and surgery (consolidation approach) [

28,

29]. The consolidation approach is usually applied for distally located high-risk rectal cancers, while for larger, more proximally located tumors, we prioritize the induction approach. Routine clinical response assessment is performed 6-8 weeks after the completion of neoadjuvant treatment, using pelvic MRI, rigid proctoscopy, and digital rectal examination. For patients exhibiting a complete clinical response (cCR) after initial treatment, particularly those with distally located tumors, a ‘watch-and-wait’ approach is now a viable option in Serbia. The neoadjuvant CRT strategy is also utilized in treating local disease recurrence following surgery. For metastatic colorectal cancer, conventional radiotherapy and stereotactic techniques are applied, particularly for metastases to the brain, bone, and liver, in conjunction with advanced systemic therapies.

3.4.4. Surgical Approaches

Although advanced surgical approaches are available at IORS, challenges in the treatment of CRC include late diagnosis of the disease, which can limit the effectiveness of surgical procedures. The decision on any type of treatment is made in a multidisciplinary manner, taking into account the disease and patient characteristics, and in accordance with relevant clinical practice guidelines [

30]. Standard surgical techniques include resection of the affected part of the colon or rectum with removal of locoregional lymph nodes. Around 350 such surgeries are performed annually at the Clinic for Oncological Surgery of IORS. Most surgeries are performed minimally invasively, laparoscopically, which reduces postoperative complications and accelerates the recovery of patients. State-of the-art surgical methods are also routinely done, such as HIPEC, liver and lung resection. In addition to radical surgeries, palliative surgery is also performed in order to alleviate the symptoms of the disease and improve the quality of life of patients.

Recently, the Serbian National Training Programme for minimally invasive colorectal surgery (LapSerb) was introduced with the aim to implement laparoscopic colorectal surgery across Serbia. Until 2023, 1456 laparoscopic colectomies were performed by 24 certified surgeons and the program included knowledge exchange, workshops, live surgeries and competency-based assessment of unedited recordings. LapSerb was successfully and safely established across the country with comparable and acceptable short-term clinical outcomes (overall mortality of 1.1% and R0 resections achieved in 97.8% of malignant colectomies) [

31].

3.4.5. Diagnostic Molecular Testing

The Pharmacogenomics Service was established at IORS within the Laboratory for Molecular Genetics in 2008. This service was developed in response to the introduction of anti-EGFR mAbs, first cetuximab (Erbitux

®, ImClone/Merck/Bristol-Myers-Squibb), and then panitumumab (Vectibix

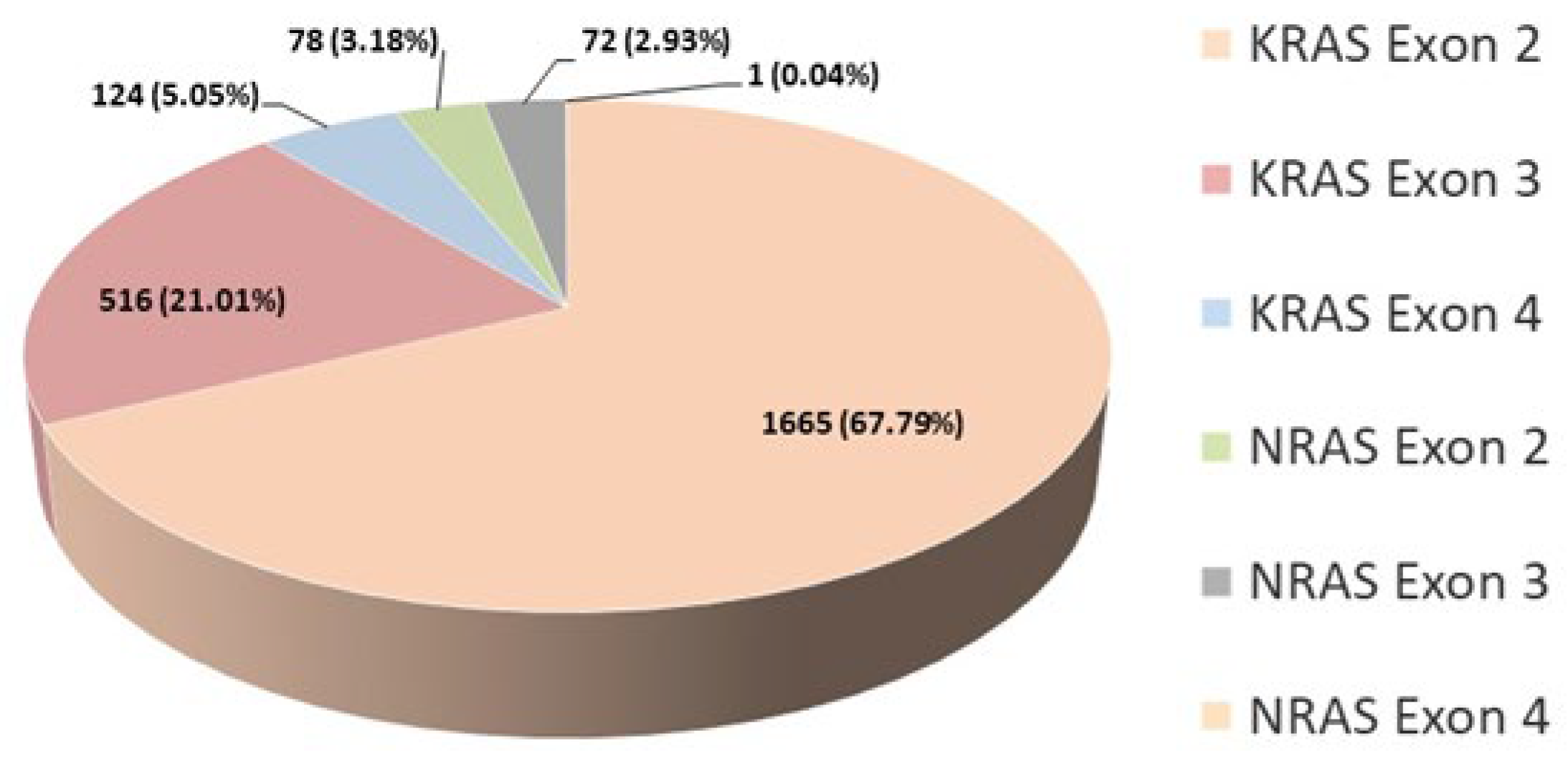

®, Amgen), as the solution for personalized oncology treatment needs. The task of the service was to fully follow the main principle of pharmacogenetics, which is to determine the optimal drug and dosage for each patient based on genetic characteristics. Until June 2024, a total of 6369 patients underwent testing for somatic mutations in the

KRAS and/or

NRAS genes. The individuals tested included 3993 males and 2366 females, with a median age of 65. In 0.16% of patients, the analysis was unsuccessful due to the inadequate quality of the isolated DNA material. Patient characteristics and mutation distribution are shown in

Table 1.

The recommendations for testing have changed over time as knowledge about the effectiveness of these agents has spread, following the world and European guidelines. Initially, only mutations in exon 2 of the

KRAS gene were analyzed [

32]. From 2013, the scope of analysis expanded to include exons 2, 3, and 4 of the

KRAS and

NRAS genes in IORS analyses. Today, testing for status

KRAS and

NRAS exons 2, 3, and 4 and

BRAF mutations is recommended in all patients at the time of mCRC diagnosis, while

RAS testing is mandatory before treatment with anti-EGFR mAbs [

33].

According to our findings, 50.43% of all tested patients exhibited a mutation in the

KRAS or

NRAS gene confirming literature data. The percentage of detected mutations per exon is shown for 2456 patients (

Figure 4). The analysis for these patients was consistently conducted using the same kit (AmoyDx

® KRAS/NRAS Mutations Detection Kit), covering all three exons in both genes. As we expected, the highest percentage of mutations was detected in exon 2 of the

KRAS gene. The total percentage of patients carrying a mutation in the

NRAS gene is 6.15%, which corresponds to literature data (

Figure 4).

At IORS, 304 patients with mCRC have been tested so far for mutations in the

BRAF gene. Out of these, 29 patients, or 9.54%, were found to have a mutation, in agreement with literature data showing that 8 to 12% of mCRC patients have a

BRAF mutation V600E [

34]. Currently, this testing is conducted in our country only for patients with

RAS wild-type status upon the specific request of the clinicians. Literature data suggests that 30% to 40% of patients have a mutation in the

KRAS gene, while up to 10% of patients have a mutation in the

NRAS gene. Together, this amounts to 50%, and according to recent research, this may be as high as 60% [

35,

36].

Since 2008, the annual number of patients with mCRC who have been tested on IORS has steadily increased until 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The global situation has impacted the healthcare system in Serbia, resulting in a decrease in the number of patients visiting doctors for reasons other than COVID-19 infection, which in turn affected the work of the Pharmacogenomics Service [

37].

Starting in 2022, there was a greater than expected increase in the number of patients undergoing testing, due to the decision by the Republic Health Insurance Fund of Serbia to approve the use of anti-EGFR mAbs as a first-line treatment for mCRC. The previous protocol limited the use of anti-EGFR mAbs to third-line treatment. In part, this increase is due to the decrease in the number of patients who visited IORS during the COVID-19 pandemic (

Figure 5) which correlates well with the detected decrease of incidence of CRC in 2020 (

Figure 1a).

All these analyses were conducted using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples (FFPE), extracting DNA using either the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Manchester, UK) or the Cobas

® DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

RAS mutation detection was conducted using various methods, including the KRAS StripAssay, TheraScreen

® K-RAS Mutation Kit on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR, TheraScreen

® KRAS RGQ PCR Kit on the Qiagen Rotor Gene Q, Cobas

® KRAS Mutation Test on the Cobas

® 4800, and AmoyDx KRAS/NRAS Mutation Detection Kit on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR or LightCycler

® 480 Instrument II [

38].

4. Liquid Biopsy Applications

Liquid biopsies are in the limelight as a minimally-invasive source of biological material able to provide information to the clinicians on the molecular composition of both the primary tumor and metastases at every stage of the clinical care pathway [

39]. Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA), although containing scarce amounts of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), can be used to identify mutations and small insertions and deletions, copy-number alterations, methylation profiles, fragment size profiles or nucleosome-protected fragments reflective of the tissue of origin [

40]. Circulating tumor cells, exosomes, tumor educated platelets and circulating RNAs have also shown promise as cancer biomarkers.

The concentration of cfDNA in blood plasma is generally positively correlated with the tumor stage, however due to high technical variation related to methods used in the pre-analytical stages (blood processing, transport, storage, cfDNA extraction) and high inter-individual physiological variation (anatomycal site of the tumor, comorbidieties, ongoing therapy, inflamation, presence of caxexia, etc.), it is not a reliable biomarker. Targeted LB assays are more specific and sufficiently sensitive to detect cancer biomarkers. Several assays based on quantitative or digital PCR or NGS can be used to detect variants to direct systemic therapies in a tumor-informed or tumor-agnostic manner. Genes recommended by the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group for testing in LBs when tumor tissue is unavaliabe or for time-critical applications, include

BRAF (for V600E mutation),

NTRK 1/2/3 fusions,

KRAS/NRAS mutations (exon 2,3,4),

ERBB2 amplification,

EGFR-ECD (for mutations in the extracellular domain S492, G465, S464, V441), along with MSI-H and TMB score [

41]. In the context of therapy selection, several clinical trials are including ctDNA to inform the decision of anti-EGFR rechallenge. The CHRONOS trial has demonstrated a clinical advantage of anti-EGFR rechallenge in patients who have no evidence of

RAS, EGFR-ECD, and

BRAF mutations in ctDNA prior to rechallenge [

42]. Thus far, NGS-based assay FoundationOne Liquid CDx (Foundation Medicine, Inc.) testing a panel of genes is the only cfDNA assay that had received pre-market approval from FDA in 2023 (Premarket Approval (PMA) (fda.gov)) for the detection of BRAF V600E alteration in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) from blood plasma (List of Cleared or Approved Companion Diagnostic Devices (In Vitro and Imaging Tools) | FDA).

Emerging applications include using methylation profiles or fragmentomics. DNA methylation based LB assays approved by the FDA for early detection of CRC are Epi proColon

® (Epigenomics AG, Berlin, Germany) and RealTime mS9 CRC Assay (Abbott Laboratories Chicago, IL, USA) to detect

SEPT9 promoter methylation, and Cologuard

® (Exact Sciences Co., Madison, WI, USA) that targets methylation changes at

BMP3 and

NDRG4 promoters and seven, point mutations in the

KRAS gene [

43]. Ongoing trials are examining the clinical utility of methylation-based multi-cancer early detection strategies. However, according to 2024. NCCN Guidelines for colon and for rectal cancer, there is not sufficient level of evidence to recommend individual genes or multi-gene testing using ctDNA assays, outside clinical trials. Similarly, at present, molecular diagnostics from liquid biopsies in CRC is not implemented as the standard-of-care at the IORS. Pilot clinical programs and scientific projects are being considered for 2025.

Nevertheless, at IORS we are engaged in several avenues of translational research using liquid biopsies. Ongoing collection of plasma and FFPE tumor material is organized within the framework of the EU Horizon STEPUPIORS project with the aim of establishing the first rectal cancer biobank in Serbia to facilitate ongoing and future translational research. The TRACEPIGEN project funded by the national Science Fund of Serbia implemented a longitudinal study prospectively collecting plasma samples from patients with advanced CRC during systemic therapy, aimed to gain understanding of the genetic and epigenetic evolution of colorectal cancer.

4.1. Significance of Extracellular Vesicles Research in CRC

Extracellular vesicles (EV) enable intercellular communication, and the most studied types are small EVs, up to 120 nm in diameter, often called “exosomes” [

44]. While studying the composition of EVs and monitoring glycosylation patterns, various vesicular non-coding RNAs, proteins, metabolites have shown potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in CRC [

45,

46,

47]. The therapeutic potential of small EVs is under investigation as they might be used as carriers of various non-coding RNAs and chemotherapeutics thanks to their unique properties (size, stability in circulation, encapsulated content, ability to pass through the membrane) [

44,

48].

In Serbia, an EV-related scientific community has emerged in 2022, with the formation of the Serbian Society for Extracellular vesicles. First studies on EVs in CRC are under way within the framework of the STEPUPIORS Horizon Europe project, evaluating their potential in profiling the response to neoadjuvant CRT in LARC from sequential plasma samples of IORS patients. Studies involving their use as diagnostic and therapeutic assets are still lacking.

5. Omics Analyses

5.1. Transcriptomics, Genomics and Proteomics

The establishment of the whole genome sequencing (WGS) method led to the discovery of driver mutations and genes in CRC. Single nucleotide variances (SNVs), structural variances (SVs), copy number alterations (CNAs), and small insertion-deletions (indels) are the most common genetic variations discovered in CRC [

49]. It was shown that genomic landscapes could be used in addition to clinicopathological features, enabling a more precise definition of the disease subgroup, a personalized approach to treatment, and early diagnosis [

50]. Genomic studies highlighted mutations that correlate with disease progression, invasiveness, and CRC pathogenesis [

51]. Transcriptome analysis, improved understanding of the transcriptional activity of CRC enabling classification of CRC into prognostic subtypes (CRPSs) [

52]. A multi-omics approach enables high-throughput insight into the colorectal cancer molecular profile [

53].

Tumor mutations showed correlation with transcriptomic profile, indicating differences in gene expression pattern between various subtypes of CRC as well as normal and CRC tissue. The state-of-the-art CRC gene expression pattern is Consensus Molecular Subtypes (CMS), which is used for the classification of tumors. CRC prognostic subtypes (CRPSs) predict overall survival (OS), regression-free survival (RFS), and survival after recurrence [

52]. Single-cell RNAseq enabled immune landscape profiling of different tumor regions and their association with CRC patient prognosis [

54]. Furthermore, the development of proteomics allowed phenotypic profiling and discovering protein level prognostic biomarkers of disease, thus enabling personalized management of CRC [

55]. High-throughput proteomic analysis conducted on rectal cancer tissue in our population indicated high predictive potential of treatment response by highlighting proteins encoded by genes

SMPDL3A, PCTP, LGMN, SYNJ2, NHLRC3, GLB1, and

RAB43 as markers of unfavorable response and

RPA2, SARNP, PCBP2, SF3B2, HNRNPF, RBBP4, MAGOHB, DUT, ERG28, and

BUB3 of favorable response [

56]. Genomic and transcriptomic studies conducted in the Serbian science community mainly focus on single gene analysis to improve clinical diagnostic and patient monitoring. Some of the many published results include detection of

KRAS and

BRAF mutations in Serbian population [

32,

57,

58] and development of less invasive assay for detection of those mutations by using ddPCR [

59]. The discovery of predictive biomarkers on mRNA level by using in silico methods indicated the importance of inflammatory response in treatment outcome while

IDO1 gene expression level shown to have predictive potential [

60]. Detection of SNPs using cost-effective methods in MTHFR gene highlighted their role in CRC risk [

61]. Serum level of circulating miR-93-5p for patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer and liver metastases shown to be a prognostic factor for early disease recurrence[

62]. Analysis of transcript

CD81-215, SMAD4-209, SMAD4-213, and

SMAD7 3′UTR variants indicated their importance in CRC and malignant transformation [

63,

64,

65].

5.2. Radiomics

The term “radiomics” was first introduced over a decade ago [

66] marking the fusion of radiology with omics sciences. As imaging technologies advanced and image resolution improved, it became obvious that medical images contain far more information than what was being utilized in routine clinical practice. This insight, along with the rise of big data analytics and machine learning, paved the way for the development of radiomics. The strength of radiomics lies in its ability to perform unselective computational texture analysis, revealing hidden prognostic information that remains unexploited by visual or computational evaluations targeting specific structures. Radiomics is a rapidly evolving field in medical imaging that involves extracting a very large number of first-, second- and higher-order quantitative statistical texture features from medical images, such as CT, MRI or PET scans. These data are then combined with other patient data and are mined with sophisticated machine learning (ML) bioinformatics tools to develop models, mostly to prognosticate binary endpoints such as therapy response or disease outcome. This approach enables personalized medicine, thus improving patient survival [

67].

The comprehensiveness of the radiomics analysis is its major advantage because radiomics analyses outperform more traditional fractal and texture analyses. which calculate only several features [

68]. However, the use of a large number of features is also a drawback of radiomics, because high dimensionality can cause overfitting, where the model becomes too complex and performs well on training data but poorly on new, unseen data. Additionally, high dimensionality can obscure the most relevant features, making it difficult to derive meaningful insights from the data. To address this problem, feature selection methods like the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) are employed to reduce the number of features included in the final model. Subsequently, machine learning classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), random forests, or neural networks are utilized to perform the classification against a binary outcome. By combining feature selection methods with machine learning algorithms, radiomics can overcome the challenges of high dimensionality, leading to more accurate and generalizable predictive models.

Radiomics technology is gaining traction in Serbia, with four studies listed on PubMed, all originating from our laboratory. Radiomics has been applied as a tool to enhance the prediction of chemoradiotherapy response of rectal cancer [

69], breast cancer metastasis [

70], chemotherapy response of osteosarcoma [

71] and radiotherapy response of meningioma [

72]. A unique approach was undertaken in breast cancer prognosis, where radiomics analysis traditionally used in 3D scans was applied to 2D histopathology slides, to assess tumor heterogeneity at the histological level [

70].

The study on LARC patients aimed to develop a machine learning model that integrates radiomics from pretreatment MRI 3D T2W contrast sequence scans with traditional clinical parameters (CP) to predict the response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT). Tumor characteristics were evaluated by calculating 1,862 radiomics features, with feature selection performed using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and multivariate regression. The models demonstrated a moderately advantageous impact of increased dimensionality, with low- and high-dimensional models, including 93 and 1862 radiomics features, respectively, achieving predictive AUCs of 0.86 and 0.90. Both models that included radiomics features outperformed the CP-only model (AUC = 0.80), which served as the benchmark for predictive performance without radiomics. These findings suggest that combining MRI radiomics with clinical features could serve as an improved predictor of nCRT response in LARC, aiding clinicians in personalizing treatment [

69].

5.3. Metabolomics

Metabolomics represents the status of all metabolites (small molecule intermediates or end products of metabolic processes) within the body and is highly correlated to disease phenotype. It can provide clinically useful biomarkers for diagnostics and patient stratification in CRC. Patient metabolomics profiles can distinguish healthy controls from CRC patients, categorize different stages of disease, and predict early or late onset disease [

73]. Also, it is helpful in the discovery of new therapeutic targets and monitoring the activity of therapeutics. Holowatyj et al. revealed that early and late-onset CRC metabolic profiles significantly differ, with further metabolic dysregulation occurring in late-onset patients [

74]. Metabolomic studies of Geijson et al. and Liu et al. compared metabolomics profiles of different stages of CRC and showed that several metabolites were differentially regulated in specific stages of CRC [

75,

76]. Many studies indicate the potential of metabolomic studies for screening purposes identifying potentially important metabolic features associated with CRC risk [

77,

78].

In Serbia, metabolomics studies are still underutilized in clinical CRC practice but represent a promising tool for identifying CRC biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity. Within the framework of the STEPUPIORS Horizon Europe project, the first retrospective and prospective metabolomics studies are under way to profile the response to neoadjuvant CRT in LARC from sequential liquid biopsy samples of patients undergoing treatment at IORS. The first results are expected in 2025.

5.4. Fragmentomics

The analysis of fragmentation patterns in cell-free DNA (cfDNA), referred to as fragmentomics, has proven to be a useful approach for extracting information from liquid biopsies without requiring mutational data [

79]. Tumour tissue releases DNA (ctDNA) that is different in size compared to healthy cells, which also displays both genetic and epigenetic changes derived from its originating cells, including fragment endpoints, specific motifs and nucleosome characteristics. Concerning CRC, a few fragmentomics-based assay models have been proposed, which managed to distinguish CRC patients from healthy controls, enabling early-stage diagnosis, risk detection and broad patient benefits [

80,

81]. As it represents an emerging field in research of cancer biomarkers, early cancer detection and diagnosis, the first fragmentomics study is under way to profile the response to neoadjuvant CRT in LARC from sequential liquid biopsy samples of patients undergoing treatment at IORS within the STEPUPIORS Horizon Europe project.

6. Discussion

Although significant improvements in CRC management have occurred globally in recent years, the high incidence of young-onset CRC and the growing elderly population due to a rise in life expectancy require a strategic approach leading to population-based systemic solutions as seen in some European countries [

82]. Similar to global trends, in Serbia there are many challenges, along with prompting issues of counseling, genetic, and fertility nature in young adults which are currently without proper systemic care at the national level. All these issues induced responses from the Serbian medical and scientific community in accelerating programs for prevention and earlier detection, increasing the availability of treatment options and modern techniques as well as scientific research focused on our population. The ongoing efforts include a global approach towards decreasing the inequity in cancer research which can lead to better treatment strategies and steer societal impact in countries with limited research and health resources, as Serbia. This might only be addressed by progressing beyond descriptions of cancer outcome differences towards a systematic, non-profit, long-term strategic initiatives and active collaborations among all relevant cancer stakeholders and existing social structures, with a focus on improving equitable access to care, improving clinical research, addressing structural barriers, and increasing awareness that results in measurable and timely action toward achieving for all. This is in line with relevant global initiatives as the ones recently launched by ESMO and ASCO [

83,

84]. Studies focusing on utilization patterns and medical cost in oncology are needed in Serbia and the Balkan region, in order to advance evidence-based policy changes with adequate return on investments.

7. Specific Challenges and Future Perspectives

Key challenges for reducing CRC incidence and mortality in Serbia remain to be addressed in the coming years:

- specific national diet high in fat and processed foods and low in fiber

- high incidence of obesity and sedentary lifestyle

- low uptake of national screening/increase awareness on the benefits of prevention and early detection

- improve diagnostic techniques and increase availability of medical equipment

- improve drug availability and reimbursement

- improve minimally invasive surgical techniques and postoperative follow-up

- introduce liquid-biopsy based molecular diagnostic approaches and follow-up

- strengthen national heath technology analysis approaches

- provide continuous training for health care workers and

- increase the number of scientific projects and funding dedicated to CRC research through interdisciplinary collaborative efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., N.N. and J.S.; methodology, M.C., N.N., M.M., A.D., A.K., M.T., M.R., A.S., L.P., M.DjC., A.Dj., M.V., V.S., J.K., V.K. and J.S.; validation, M.C., N.N., S.N., S.SR., R.J. and J.S.; formal analysis, M.C., N.N., M.M., A.D., A.K., M.T., M.R., A.S., L.P., M.DjC., A.Dj., M.V., V.S., J.K., V.K. and J.S.; investigation, M.C., N.N., M.M., A.D., A.K., M.T., M.R., A.S., L.P., M.DjC., A.Dj., M.V., V.S., J.K., V.K. and J.S.; resources, M.C., A.K. R.J. and J.S.; data curation, M.C., N.N., M.M., A.D., A.K., M.T., M.R., A.S., L.P., M.DjC., A.Dj., M.V., V.S., J.K., V.K. and J.S..; writing—original draft preparation, M.C., N.N., M.M., A.D., A.K., M.T., M.R., A.S., L.P., M.DjC., A.Dj., M.V., V.S., J.K., V.K., and J.S.; writing—review and editing, M.C., N.N., M.M., A.D., A.K., M.T., M.R., A.S., L.P., M.DjC., A.Dj., M.V., V.S., J.K., V.K., S.N., S.SR., R.J. and J.S.; supervision, M.C., S.N., S.S.R., A.K., R.J. and J.S.; project administration, M.C., A.Dj and J.S.; funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Horizon Europe STEPUPIORS Project (HORIZON-WIDERA-2021-ACCESS-03, European Commission, Agreement No. 101079217) and the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Agreement No. 451-03-66/2024-03/ 200043).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All clinical, molecular testing and research analyses have been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia. All experiments have been performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/) with the dataset identifier PXD040451. The radiomics data are openly available in Zenodo, at doi: 10.5281/zenodo.8379940. Other data are not publicly available due to ethics restrictions as their containing information might compromise the privacy of patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the PROMIS TRACEPIGEN Project (Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, No. 6060876).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Colorectal Cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and Mortality Estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilic, M.; Ilic, I. Cancer Mortality in Serbia, 1991--2015: An Age-Period-Cohort and Joinpoint Regression Analysis. Cancer Commun. 2018, 38, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlajinac, H.; Šipetić-Grujičić, S.; Janković, S.; Marinković, J.; Kocev, N.; Marković-Denić, L.; Bjegović, V. Burden of Cancer in Serbia. Croat. Med. J. 2010, 47, 843–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, J.; Stamenkovic, Z.; Stevanovic, A.; Terzic, N.; Kissimova-Skarbek, K.; Tozija, F.; Mechili, E.A.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Terzic-Supic, Z.; Vasic, M.; et al. The Burden of Breast, Cervical, and Colon and Rectum Cancer in the Balkan Countries, 1990-2019 and Forecast to 2030. Arch. Public Health 2023, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekic, B.; Dragojevic-Simic, V.; Jakovljevic, M.; Pilipovic, F.; Simic, R.; Zivic, R.; Radovanovic, D.; Rancic, N. Medical Cost of Colorectal Cancer Services in Serbia Between 2014 and 2017: National Data Report. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, A.; Mitrašinović, P.; Mićanović, D.; Grujičić, S.; Originalni, R. Trends in Morbidity and Mortality of Colorectal Cancer in Men and Women of Central Serbia during the Period 1999-2020. Zdr. zaštita 2023, 52, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Public Health of Serbia “Dr Milan Jovanović Batut” Malignant Tumors in Serbia 2021_Serbian Cancer Registry; 2021.

- Nikolic, N.; Spasic, J.; Stanic, N.; Nikolic, V.; Radosavljevic, D. Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer in Serbia: Tertiary Cancer Center Experience. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshandel, G.; Ghasemi-Kebria, F.; Malekzadeh, R. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Cancers 2024, Vol. 16, Page 1530 2024, 16, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scepanovic, M.; Jovanovic, O.; Keber, D.; Jovanovic, I.; Miljus, D.; Nikolic, G.; Kovacevic, B.; Pavlovic, A.; Dugalic, P.; Nagorni, A.; et al. Faecal Occult Blood Screening for Colorectal Cancer in Serbia: A Pilot Study. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 26, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roht, L.; Laidre, P.; Tooming, M.; Tõnisson, N.; Nõukas, M.; Nurm, M.; Roomere, H.; Rekker, K.; Toome, K.; Fjodorova, O.; et al. The Prevalence and Molecular Landscape of Lynch Syndrome in the Affected and General Population. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Ghazaleh, N.; Kaushik, V.; Gorelik, A.; Jenkins, M.; Macrae, F. Worldwide Prevalence of Lynch Syndrome in Patients with Colorectal Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Valentin, M.; Sampson, J.R.; Seppälä, T.T.; ten Broeke, S.W.; Plazzer, J.P.; Nakken, S.; Engel, C.; Aretz, S.; Jenkins, M.A.; Sunde, L.; et al. Cancer Risks by Gene, Age, and Gender in 6350 Carriers of Pathogenic Mismatch Repair Variants: Findings from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.J.; Caruana, M.; McLoughlin, K.; Killen, J.; Simms, K.; Taylor, N.; Frayling, I.M.; Coupé, V.M.H.; Boussioutas, A.; Trainer, A.H.; et al. The Predicted Effect and Cost-Effectiveness of Tailoring Colonoscopic Surveillance According to Mismatch Repair Gene in Patients with Lynch Syndrome. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 1831–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppälä, T.T.; Latchford, A.; Negoi, I.; Sampaio Soares, A.; Jimenez-Rodriguez, R.; Evans, D.G.; Ryan, N.; Crosbie, E.J.; Dominguez-Valentin, M.; Burn, J.; et al. European Guidelines from the EHTG and ESCP for Lynch Syndrome: An Updated Third Edition of the Mallorca Guidelines Based on Gene and Gender. Br. J. Surg. 2021, 108, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, L.R.; Johnson, V.; Cummings, C.; Fisher, S.; Risby, P.; Eftekhar Sadat, A.T.; Cranston, T.; Izatt, L.; Sasieni, P.; Hodgson, S. V.; et al. Refining the Amsterdam Criteria and Bethesda Guidelines: Testing Algorithms for the Prediction of Mismatch Repair Mutation Status in the Familial Cancer Clinic. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4934–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnetson, R.A.; Tenesa, A.; Farrington, S.M.; Nicholl, I.D.; Cetnarskyj, R.; Porteous, M.E.; Campbell, H.; Dunlop, M.G. Identification and Survival of Carriers of Mutations in DNA Mismatch-Repair Genes in Colon Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2751–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastrinos, F.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Mercado, R.; Balmaña, J.; Holter, S.; Gallinger, S.; Siegmund, K.D.; Church, J.M.; Jenkins, M.A.; Lindor, N.M.; et al. The PREMM(1,2,6) Model Predicts Risk of MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 Germline Mutations Based on Cancer History. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 73–81.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argilés, G.; Tabernero, J.; Labianca, R.; Hochhauser, D.; Salazar, R.; Iveson, T.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Quirke, P.; Yoshino, T.; Taieb, J.; et al. Localised Colon Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagtegaal, I.D.; Odze, R.D.; Klimstra, D.; Paradis, V.; Rugge, M.; Schirmacher, P.; Washington, K.M.; Carneiro, F.; Cree, I.A. The 2019 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Histopathology 2020, 76, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolic, N.; Radosavljevic, D.; Gavrilovic, D.; Nikolic, V.; Stanic, N.; Spasic, J.; Cacev, T.; Castellvi-Bel, S.; Cavic, M.; Jankovic, G. Prognostic Factors for Post-Recurrence Survival in Stage II and III Colorectal Carcinoma Patients. Medicina (B. Aires). 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maravic, Z.; Rawicka, I.; Benedict, A.; Wyrwicz, L.; Horvath, A.; Fotaki, V.; Carrato, A.; Borras, J.M.; Ruiz-Casado, A.; Petrányi, A.; et al. A European Survey on the Insights of Patients Living with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The Patient Journey before, during and after Diagnosis - an Eastern European Perspective. ESMO open 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alese, O.B.; Wu, C.; Chapin, W.J.; Ulanja, M.B.; Zheng-Lin, B.; Amankwah, M.; Eads, J. Update on Emerging Therapies for Advanced Colorectal Cancer. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. book. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Annu. Meet. 2023, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosset, J.F.; Calais, G.; Mineur, L.; Maingon, P.; Stojanovic-Rundic, S.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Bardet, E.; Beny, A.; Ollier, J.C.; Bolla, M.; et al. Fluorouracil-Based Adjuvant Chemotherapy after Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy in Rectal Cancer: Long-Term Results of the EORTC 22921 Randomised Study. Lancet. Oncol. 2014, 15, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, V.; Gambacorta, M.A.; Barbaro, B.; Chiloiro, G.; Coco, C.; Das, P.; Fanfani, F.; Joye, I.; Kachnic, L.; Maingon, P.; et al. International Consensus Guidelines on Clinical Target Volume Delineation in Rectal Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2016, 120, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T.; Bosset, J.F.; Etienne, P.L.; Rio, E.; François, É.; Mesgouez-Nebout, N.; Vendrely, V.; Artignan, X.; Bouché, O.; Gargot, D.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX and Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy for Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer (UNICANCER-PRODIGE 23): A Multicentre, Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet. Oncol. 2021, 22, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadoer, R.R.; Dijkstra, E.A.; van Etten, B.; Marijnen, C.A.M.; Putter, H.; Kranenbarg, E.M.K.; Roodvoets, A.G.H.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Blomqvist, L.K.; et al. Short-Course Radiotherapy Followed by Chemotherapy before Total Mesorectal Excision (TME) versus Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy, TME, and Optional Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer (RAPIDO): A Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet. Oncol. 2021, 22, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucarini, A.; Garbarino, G.M.; Orlandi, P.; Garofalo, E.; Bragaglia, L.; Laracca, G.G.; Canali, G.; Pecoraro, A.; Mercantini, P. From “Cure” to “Care”: The Role of the MultiDisciplinary Team on Colorectal Cancer Patients’ Satisfaction and Oncological Outcomes. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljan, C.; Gendia, A.; Rehman, M.U.R.; Blagoje, D.; Mladen, J.; Igor, K.; Nebojsa, S.; Aleksandar, G.; Zlatibor, L.; Ahmed, J.; et al. Serbian National Training Programme for Minimally Invasive Colorectal Surgery (LapSerb): Short-Term Clinical Outcomes of over 1400 Colorectal Resections. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 2943–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, K.; Malisic, E.; Cavic, M.; Krivokuca, A.; Dobricic, J.; Jankovic, R. KRAS and BRAF Mutations in Serbian Patients with Colorectal Cancer. J. BUON. 2012, 17, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Roselló, S.; Arnold, D.; Normanno, N.; Taïeb, J.; Seligmann, J.; De Baere, T.; Osterlund, P.; Yoshino, T.; et al. Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up ☆. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saoudi González, N.; Ros, J.; Baraibar, I.; Salvà, F.; Rodríguez-Castells, M.; Alcaraz, A.; García, A.; Tabernero, J.; Élez, E. Cetuximab as a Key Partner in Personalized Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesti, T.; Rebersek, M.; Ocvirk, J. The Five-Year KRAS, NRAS and BRAF Analysis Results and Treatment Patterns in Daily Clinical Practice in Slovenia in 1st Line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal (MCRC) Patients with RAS Wild-Type Tumour (WtRAS) – A Real- Life Data Report 2013–2018. Radiol. Oncol. 2023, 57, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, D.; Dobre, M.; Panaitescu, E.; Bîrlă, R.; Iosif, C.; Hoara, P.; Caragui, A.; Boeriu, M.; Constantinoiu, S.; Ardeleanu, C. Prognostic Significance of KRAS Gene Mutations in Colorectal Cancer - Preliminary Study. J. Med. Life 2014, 7, 581. [Google Scholar]

- Cavic, M.; Krivokuca, A.; Boljevic, I.; Spasic, J.; Mihajlovic, M.; Pavlovic, M.; Damjanovic, A.; Radosavljevic, D.; Jankovic, R. Exploring the Real-World Effect of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic on the Molecular Diagnostics for Cancer Patients and High-Risk Individuals. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 21, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavic, M.; Krivokuca, A.; Boljevic, I.; Brotto, K.; Jovanovic, K.; Tanic, M.; Filipovic, L.; Zec, M.; Malisic, E.; Jankovic, R.; et al. Pharmacogenetics in Cancer Therapy - 8 Years of Experience at the Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia. J. BUON. 2016, 21, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Song, P.; Wu, L.R.; Yan, Y.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Chu, T.; Kwong, L.N.; Patel, A.A.; Zhang, D.Y. Limitations and Opportunities of Technologies for the Analysis of Cell-Free DNA in Cancer Diagnostics. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022 63 2022, 6, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pardo, M.; Makarem, M.; Li, J.J.N.; Kelly, D.; Leighl, N.B. Integrating Circulating-Free DNA (CfDNA) Analysis into Clinical Practice: Opportunities and Challenges. Br. J. Cancer 2022 1274 2022, 127, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.; Attard, G.; Bidard, F.C.; Curigliano, G.; De Mattos-Arruda, L.; Diehn, M.; Italiano, A.; Lindberg, J.; Merker, J.D.; Montagut, C.; et al. ESMO Recommendations on the Use of Circulating Tumour DNA Assays for Patients with Cancer: A Report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 750–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagut, C.; Argilés, G.; Ciardiello, F.; Poulsen, T.T.; Dienstmann, R.; Kragh, M.; Kopetz, S.; Lindsted, T.; Ding, C.; Vidal, J.; et al. Efficacy of Sym004 in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer With Acquired Resistance to Anti-EGFR Therapy and Molecularly Selected by Circulating Tumor DNA Analyses: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taryma-Leśniak, O.; Sokolowska, K.E.; Wojdacz, T.K. Current Status of Development of Methylation Biomarkers for in Vitro Diagnostic IVD Applications. Clin. Epigenetics 2020, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotelevets, L.; Chastre, E. Extracellular Vesicles in Colorectal Cancer: From Tumor Growth and Metastasis to Biomarkers and Nanomedications. Cancers 2023, Vol. 15, Page 1107 2023, 15, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eylem, C.C.; Yilmaz, M.; Derkus, B.; Nemutlu, E.; Camci, C.B.; Yilmaz, E.; Turkoglu, M.A.; Aytac, B.; Ozyurt, N.; Emregul, E. Untargeted Multi-Omic Analysis of Colorectal Cancer-Specific Exosomes Reveals Joint Pathways of Colorectal Cancer in Both Clinical Samples and Cell Culture. Cancer Lett. 2020, 469, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, L.; Bu, F.; Meng, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, L.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, S. Circulating Small Extracellular Vesicle RNA Profiling for the Detection of T1a Stage Colorectal Cancer and Precancerous Advanced Adenoma. Elife 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fang, Y.; Dai, S.; Jiang, K.; Shen, L.; Zhao, J.; Huang, K.; Zhou, X.; Ding, K. Characterization and Proteomic Analysis of Plasma-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Patients. Cell. Oncol. (Dordrecht, Netherlands) 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Yu, C.; Johann Helwig, E.; Li, Y. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Colorectal Cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, A.J.; Gruber, A.J.; Kinnersley, B.; Chubb, D.; Frangou, A.; Caravagna, G.; Noyvert, B.; Lakatos, E.; Wood, H.M.; Thorn, S.; et al. The Genomic Landscape of 2,023 Colorectal Cancers. Nat. 2024 6338028 2024, 633, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Kendrick, C.D.; Ramanathan, R.K.; Graham, R.P.; Kossick, K.F.; Boardman, L.A.; Barrett, M.T. Genomic Landscape of Diploid and Aneuploid Microsatellite Stable Early Onset Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Reports 2024 141 2024, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.C.; Bodmer, W.F. Genomic Landscape of Colorectal Carcinogenesis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 148, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.; Li, F.; Wu, M.; Luo, T.; Hammarström, K.; Torell, E.; Ljuslinder, I.; Mezheyeuski, A.; Edqvist, P.-H.; Löfgren-Burström, A.; et al. Prognostic Genome and Transcriptome Signatures in Colorectal Cancers. Nat. 2024 6338028 2024, 633, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, S.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, D.; Meng, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Fang, L. Multi-Omic Profiling Reveals Associations between the Gut Microbiome, Host Genome and Transcriptome in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.; Fu, G.; Huang, M.; Kao, X.; Zhu, J.; Dai, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Chu, X.; et al. ScRNA-Seq of Colorectal Cancer Shows Regional Immune Atlas with the Function of CD20+ B Cells. Cancer Lett. 2024, 584, 216664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Ma, F.; Jiang, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Tan, S.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Z.; et al. Proteomic Characterization of the Colorectal Cancer Response to Chemoradiation and Targeted Therapies Reveals Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Cell reports. Med. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, A.; Samiotaki, M.; Lygirou, V.; Marinkovic, M.; Nikolic, V.; Stojanovic-Rundic, S.; Jankovic, R.; Vlahou, A.; Panayotou, G.; Fijneman, R.J.A.; et al. Data-Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry Analysis of FFPE Rectal Cancer Samples Offers In-Depth Proteomics Characterization of the Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotto, K.; Malisic, E.; Cavic, M.; Krivokuca, A.; Jankovic, R. The Usability of Allele-Specific PCR and Reverse-Hybridization Assays for KRAS Genotyping in Serbian Colorectal Cancer Patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajnović, M.; Marković, B.; Knežević-Ušaj, S.; Nikolić, I.; Stanojević, M.; Nikolić, V.; Šiljić, M.; Jovanović Ćupić, S.; Dimitrijević, B. Locally Advanced Rectal Cancers with Simultaneous Occurrence of KRAS Mutation and High VEGF Expression Show Invasive Characteristics. Pathol. - Res. Pract. 2016, 212, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmrzljak, U.P.; Košir, R.; Krivokapić, Z.; Radojković, D.; Nikolić, A. Detection of Somatic Mutations with DdPCR from Liquid Biopsy of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Genes 2021, Vol. 12, Page 289 2021, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinkovic, M.; Stojanovic-Rundic, S.; Stanojevic, A.; Ostojic, M.; Gavrilovic, D.; Jankovic, R.; Maksimovic, N.; Stroggilos, R.; Zoidakis, J.; Castellví-Bel, S.; et al. Exploring Novel Genetic and Hematological Predictors of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1245594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, A.; Spasic, J.; Marinkovic, M.; Stojanovic-Rundic, S.; Jankovic, R.; Djuric, A.; Zoidakis, J.; Fijneman, R.J.A.; Castellvi-Bel, S.; Cavic, M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase Polymorphic Variants C677T and A1298C in Rectal Cancer in Slavic Population: Significance for Cancer Risk and Response to Chemoradiotherapy. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1299599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despotović, J.; Bogdanović, A.; Dragičević, S.; Galun, D.; Krivokapić, Z.; Nikolić, A. Prognostic Potential of Circulating MiR-93-5p in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases. Neoplasma 2022, 69, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosic, J.; Miladinov, M.; Dragicevic, S.; Eric, K.; Bogdanovic, A.; Krivokapic, Z.; Nikolic, A. Genetic Analysis and Allele-Specific Expression of SMAD7 3′UTR Variants in Human Colorectal Cancer Reveal a Novel Somatic Variant Exhibiting Allelic Imbalance. Gene 2023, 859, 147217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babic, T.; Ugrin, M.; Jeremic, S.; Kojic, M.; Dinic, J.; Djeri, B.B.; Zoidakis, J.; Nikolic, A. Dysregulation of Transcripts SMAD4-209 and SMAD4-213 and Their Respective Promoters in Colon Cancer Cell Lines. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 5118–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanovic, E.; Babic, T.; Dragicevic, S.; Kmezic, S.; Nikolic, A. Transcript CD81-215 May Be a Long Noncoding RNA of Stromal Origin with Tumor-Promoting Role in Colon Cancer. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2023, 41, 1503–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; Rios-Velazquez, E.; Leijenaar, R.; Carvalho, S.; Van Stiphout, R.G.P.M.; Granton, P.; Zegers, C.M.L.; Gillies, R.; Boellard, R.; Dekker, A.; et al. Radiomics: Extracting More Information from Medical Images Using Advanced Feature Analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Schabath, M.B. Radiomics Improves Cancer Screening and Early Detection. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2020, 29, 2556–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djuričić, G.J.; Radulovic, M.; Sopta, J.P.; Nikitović, M.; Milošević, N.T. Fractal and Gray Level Cooccurrence Matrix Computational Analysis of Primary Osteosarcoma Magnetic Resonance Images Predicts the Chemotherapy Response. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinkovic, M.; Stojanovic-Rundic, S.; Stanojevic, A.; Tomasevic, A.; Jankovic, R.; Zoidakis, J.; Castellví-Bel, S.; Fijneman, R.J.A.; Cavic, M.; Radulovic, M. Performance and Dimensionality of Pretreatment MRI Radiomics in Rectal Carcinoma Chemoradiotherapy Prediction. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulović, M.; Li, X.; Djuričić, G.J.; Milovanović, J.; Todorović Raković, N.; Vujasinović, T.; Banovac, D.; Kanjer, K. Bridging Histopathology and Radiomics Toward Prognosis of Metastasis in Early Breast Cancer. Microsc. Microanal. 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuričić, G.J.; Ahammer, H.; Rajković, S.; Kovač, J.D.; Milošević, Z.; Sopta, J.P.; Radulovic, M. Directionally Sensitive Fractal Radiomics Compatible With Irregularly Shaped Magnetic Resonance Tumor Regions of Interest: Association With Osteosarcoma Chemoresistance. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2023, 57, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckter, H.; Radulovic, M.; Trivodaliev, K.; Vranes, V.; Joaquin, J.; Hernandez, W.; Mota, A.; Bido, J.; Hernandez, G.; Rivera, D.; et al. MRI Radiomics in the Prediction of the Volumetric Response in Meningiomas after Gamma Knife Radiosurgery. J. Neurooncol. 2022, 159, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, A.; Choueiry, F.; Jin, N.; Mo, X.; Zhu, J. The Application of Metabolomics in Recent Colorectal Cancer Studies: A State-of-the-Art Review. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holowatyj, A.N.; Gigic, B.; Herpel, E.; Scalbert, A.; Schneider, M.; Ulrich, C.M.; Achaintre, D.; Brezina, S.; van Duijnhoven, F.J.B.; Gsur, A.; et al. Distinct Molecular Phenotype of Sporadic Colorectal Cancers Among Young Patients Based on Multi-Omics Analysis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geijsen, A.J.M.R.; van Roekel, E.H.; van Duijnhoven, F.J.B.; Achaintre, D.; Bachleitner-Hofmann, T.; Baierl, A.; Bergmann, M.M.; Boehm, J.; Bours, M.J.L.; Brenner, H.; et al. Plasma Metabolites Associated with Colorectal Cancer Stage: Findings from an International Consortium. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Peng, F.; Yu, J.; Tan, Z.; Rao, T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Peng, J. LC-MS-Based Lipid Profile in Colorectal Cancer Patients: TAGs Are the Main Disturbed Lipid Markers of Colorectal Cancer Progression. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 411, 5079–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troisi, J.; Tafuro, M.; Lombardi, M.; Scala, G.; Richards, S.M.; Symes, S.J.K.; Ascierto, P.A.; Delrio, P.; Tatangelo, F.; Buonerba, C.; et al. A Metabolomics-Based Screening Proposal for Colorectal Cancer. Metabolites 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidman, L.; Zheng, R.; Bodén, S.; Ribbenstedt, A.; Gunter, M.J.; Palmqvist, R.; Harlid, S.; Brunius, C.; Van Guelpen, B. Untargeted Plasma Metabolomics and Risk of Colorectal Cancer-an Analysis Nested within a Large-Scale Prospective Cohort. Cancer Metab. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdenrieder, S.; Bronkhorst, A.; Ding, S.C.; Dennis Lo, Y.M. Cell-Free DNA Fragmentomics in Liquid Biopsy. Diagnostics 2022, Vol. 12, Page 978 2022, 12, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, N.; Wu, X.; Tang, W.; Bao, H.; Si, C.; Shao, P.; Li, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, D.; et al. Multi-Dimensional Fragmentomics Enables Early and Accurate Detection of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, S.; Leal, A.; Phallen, J.; Fiksel, J.; Adleff, V.; Bruhm, D.C.; Jensen, S.Ø.; Medina, J.E.; Hruban, C.; White, J.R.; et al. Genome-Wide Cell-Free DNA Fragmentation in Patients with Cancer. Nature 2019, 570, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisse, P.H.A.; de Klaver, W.; van Wifferen, F.; van Maaren-Meijer, F.G.; van Ingen, H.E.; Meiqari, L.; Huitink, I.; Bierkens, M.; Lemmens, M.; Greuter, M.J.E.; et al. The Multitarget Faecal Immunochemical Test for Improving Stool-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Programmes: A Dutch Population-Based, Paired-Design, Intervention Study. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.I.; Lopez, A.M.; Blackstock, W.; Reeder-Hayes, K.; Allyn Moushey, E.; Phillips, J.; Tap, W. Cancer Disparities and Health Equity: A Policy Statement From the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcellini, A.; Dal Mas, F.; Paoloni, P.; Loap, P.; Cobianchi, L.; Locati, L.; Rodríguez-Luna, M.R.; Orlandi, E. Please Mind the Gap—about Equity and Access to Care in Oncology. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).