1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies and the leading cause of cancer-related death in the digestive system. Most CRCs arise through the chromosomal instability (CIN) pathway, typically initiated by inactivation of the APC gene, characterized by loss of tumor suppressor genes, activation of oncogenes, and widespread genetic alterations. A less frequent pathway (10–15%), referred to as the mutator phenotype or microsatellite instability (MSI) pathway, results from mutations in genes encoding DNA mismatch repair (MMR) proteins. This leads to the accumulation of numerous genetic errors. The majority of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancers (HNPCC) and a proportion of sporadic CRCs (10–15%) exhibit MSI, a molecular hallmark useful for detection. [

1,

2]

CRC tumors harboring

BRAF mutations and/or high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) represent clinically and pathologically distinct subgroups with different prognoses.[

3,

4,

5] Approximately 2%–15% of CRCs exhibit

BRAF mutations, with the

V600E mutation (c.1799T>A, p.Val600Glu) being the most prevalent.[

6,

7] MSI-H is observed in about 12%–15% of all CRCs and around 4% of metastatic CRCs. MSI-H status alone has generally been associated with a more favorable prognosis, as these tumors are typically diagnosed at earlier stages and are more likely to respond to immunotherapy, particularly to immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis.[

8]

Furthermore, the presence of the

BRAF V600E mutation has been associated with tumors located predominantly in the right colon, poor differentiation, and a higher prevalence among female patients.[

7] This mutation has also been specifically correlated with methylation of the MLH1 gene promoter, a common mechanism in sporadic MSI-H tumors.[

9,

10]

The status of

BRAF and MSI has been significantly linked to metastatic dissemination patterns and prognosis in CRC patients.

BRAF mutations, particularly in microsatellite-stable (MSS) tumors, have been associated with worse outcomes, including decreased overall survival, disease-specific survival, and progression-free survival.[

11] Accurate assessment of

BRAF and MSI status is therefore crucial not only for prognostic stratification but also for guiding therapeutic decision-making in CRC.[

7] While the presence of

BRAF mutations predicts a limited response to certain targeted therapies—such as cetuximab and panitumumab—efficacy can be improved when combined with anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies. A combination of encorafenib, cetuximab, and binimetinib has shown significantly prolonged overall survival and higher response rates compared to standard therapy in patients with metastatic CRC harboring

BRAF V600 mutations.[

12]

Likewise, MSI-H status has emerged as a key factor indicating reduced benefit from conventional chemotherapy, particularly in stage II and III tumors, which show limited response to adjuvant 5-FU-based regimens.[

13]

MSI status can be determined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or immunohistochemistry (IHC) to assess MMR protein expression. Detection of

BRAF mutations—typically the

V600E variant—can be performed using real-time PCR-based kits and, to a lesser extent, by Sanger sequencing or IHC with specific antibodies. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has been proposed as a comprehensive tool for genomic profiling, enabling simultaneous detection of multiple gene mutations, including

BRAF, as well as assessment of MSI status and tumor mutational burden (TMB).[

14]

Despite increasing knowledge of the roles of BRAF and MSI in CRC, challenges remain in interpreting results and integrating this information into optimal clinical practice, particularly with regard to metastatic patterns and therapeutic responsiveness.

NGS has proven to be a valuable tool for the molecular diagnosis and treatment planning of CRC, especially in patients with MSI or deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) protein expression. Its advantages include providing a comprehensive overview of the tumor’s molecular profile, identifying patients unlikely to benefit from chemotherapy, selecting those who are likely to respond to immunotherapy, enabling earlier access to targeted therapies (currently approved for advanced or metastatic stages), and enhancing overall prognostic accuracy. By facilitating more personalized and effective treatment from the early stages, the upfront use of NGS has the potential to improve overall outcomes in CRC patients.[

15,

16]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design

An observational, retrospective, and cross-sectional study was conducted on patients diagnosed with sporadic colorectal cancer (sCRC). Mutations in the KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF genes, as well as microsatellite instability (MSI), were analyzed using next-generation sequencing (NGS). Additionally, NGS results were compared with conventional techniques, such as real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry, using pseudoanonymized cases diagnosed in Spain and provided by the pathology laboratory Analiza.

2.2. Population and Case Selection

A total of 648 cases with histologically confirmed colon adenocarcinoma were retrospectively and cross-sectionally reviewed. Among them, 166 cases had partial molecular data available, and 42 cases were ultimately included in the final analysis, as they contained all molecular markers relevant to this study.

Case selection was conducted in two phases. Initially, patients diagnosed between January 1, 2024, and May 31, 2024, were screened using broader inclusion criteria. Subsequently, the retrospective search was extended up to February 5, 2025, including cases diagnosed from January 1, 2022, onwards, applying stricter criteria to obtain a more homogeneous cohort with complete molecular profiles.

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of sporadic colorectal cancer.

Availability of complete sequencing data for KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and MSI.

Sufficient tumor tissue for molecular analysis.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Cases of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome at the time of diagnosis.

Patients lacking complete information regarding the genes studied or MSI status.

Inadequate or degraded samples unsuitable for molecular testing.

2.3. Molecular Analysis Procedures

2.3.1. DNA Extraction

Tumor DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples using standardized commercial kits (QIAamp DSP FFPE Tissue Kit, Qiagen). DNA concentration and purity were assessed by fluorometric quantification.

2.3.2 Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) with Action OncoKitDx® Panel

The Action OncoKitDx panel (Health in Code Group, Spain) is designed to analyze genetic alterations across 59 genes relevant to solid tumor development. The panel detects point mutations (substitutions, deletions, insertions), copy number variations, and rearrangements, all of which have diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic significance, including potential as druggable targets or predictive biomarkers for approved or investigational targeted therapies. It also includes MSI analysis, relevant in the context of immunotherapy, and pharmacogenetic profiling of variants associated with chemotherapy toxicity or efficacy.

The Action OncoKitDx panel allows full exon sequencing of KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF genes. MSI is assessed through a panel of 110 microsatellite regions. A minimum of 99 evaluable markers is required, and classification is based on the percentage of unstable markers as follows: high MSI (31–100%, MSI-H), low MSI (21–30%, MSI-L), microsatellite stable (0–17%, MSS), and inconclusive results (18–20%)

The panel is prepared using an automated workflow with the Magnis Dx NGS Prep System (Agilent). After DNA extraction, samples undergo enzymatic fragmentation and enrichment of target regions via hybridization with capture probes using SureSelectXT HS technology, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. High-throughput NGS is performed on the NextSeq 550 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, US) using paired-end sequencing (2 × 75 bp) by cyclic reversible termination chemistry. This allows detection of point mutations and larger sequence alterations in the targeted genes.

Bioinformatic analysis is performed using a dedicated pipeline through the Data Genomics platform (www.datagenomics.es). It includes alignment of reads to the reference genome (GRCh37/hg19), quality filtering, and variant calling. Variant nomenclature follows the guidelines of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS; www.hgvs.org).

Analytical validation and clinical utility of the Action OncoKitDx panel have been established (Martínez-Fernández et al. J Pers Med 2021; 11:360. doi:10.3390/jpm11050360). Both the panel and the Data Genomics software are CE-IVD certified.

According to the manufacturer, the panel can detect alterations present at a minimum allele frequency of 5%. Detection may be compromised if sequencing depth is below 200×. To achieve this detection threshold, a minimum tumor cellularity of 30% is recommended, along with input DNA quantity between 50–200 ng and a DNA Integrity Number (DIN) >3. For MSI interpretation, the recommended tumor cellularity is also ≥30%. Samples with lower cellularity or suboptimal DNA quality may still be analyzed, though with reduced sensitivity and specificity.

2.3.3. Determination of Microsatellite Instability (MSI)

MSI status was assessed using two complementary techniques:

NGS, as described above, using the Action OncoKitDx panel.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC), by evaluating the expression of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) proteins MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.

2.3.4. IHC Interpretation Criteria for MMR Protein Expression

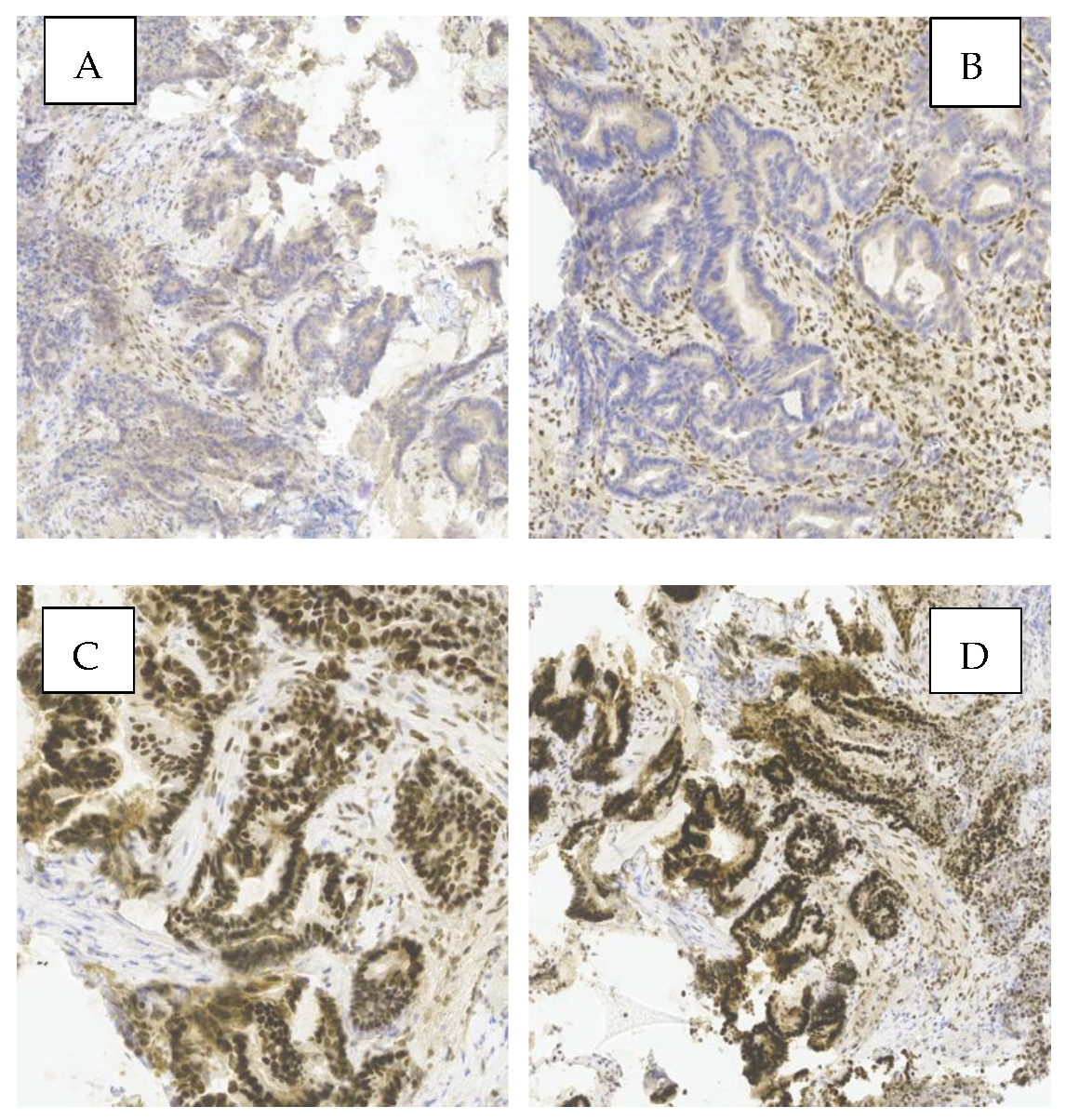

Figure 1 shows a representative example of MMR protein expression in one of the analyzed tumors. Loss of nuclear expression of PMS2 and MLH1 (images A and B), along with preserved expression of MSH2 and MSH6 (images C and D), indicates a deficient MMR (dMMR) phenotype. This pattern suggests probable MLH1 inactivation, commonly due to promoter hypermethylation or gene mutation.

Simultaneous loss of MLH1 and PMS2 typically reflects MLH1 inactivation, since PMS2 stability and expression depend on MLH1—frequently observed in sporadic MSI tumors without BRAF mutation. In contrast, isolated PMS2 loss may indicate Lynch syndrome.

Images A and B show absence of nuclear staining for PMS2 and MLH1 in tumor cells, while images C and D display strong nuclear staining for MSH2 and MSH6, consistent with preserved expression.

Immunohistochemical evaluation of MMR proteins in sporadic CRC is a fundamental diagnostic tool. These findings underscore the clinical value of IHC in identifying MMR system deficiencies, with implications for prognosis and eligibility for targeted therapies.

Nuclear staining in tumor cells was interpreted as positive expression of the corresponding marker. Cases with preserved expression of all four proteins were classified as proficient MMR (pMMR), whereas loss of expression of at least one protein was classified as deficient MMR (dMMR).

2.3.5. Real-Time PCR: Idylla KRAS Mutation Test and Idylla NRAS-BRAF Mutation Test

KRAS mutation analysis was performed using the Idylla™ KRAS Mutation Test kit and the Idylla™ platform (Biocartis). This is an in vitro diagnostic assay that enables qualitative detection of 21 mutations in codons 12, 13, 59, 61, 117, and 146 of the KRAS gene through a fully automated process that integrates target region amplification and real-time PCR-based detection.

The analysis of NRAS and BRAF mutations was conducted using the Idylla™ NRAS-BRAF Mutation Test kit and the Idylla™ platform (Biocartis). This in vitro diagnostic test allows for qualitative detection of 18 mutations in codons 12, 13, 59, 61, 117, and 146 of the NRAS gene, as well as 5 mutations in codon 600 of the BRAF gene, through an automated process involving target amplification and real-time PCR detection.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted to determine the frequency of mutations in KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF, as well as the presence of microsatellite instability (MSI). To assess associations between gene mutations and MSI status, the following statistical methods were used:

Chi-square test (χ²) and Fisher’s exact test, depending on data distribution.

Calculation of odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Jamovi software.

2.5. Artificial Inteligence

In order to optimize the presentation of the results, artificial intelligence tools (ChatGPT, OpenAI) were employed to structure a table that clearly and accurately represented the findings from the descriptive analysis previously performed by the author. Additionally, these tools were used to support the interpretation and synthesis of the results obtained from the comparative analysis, once the statistical processing of the data had been completed.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Study

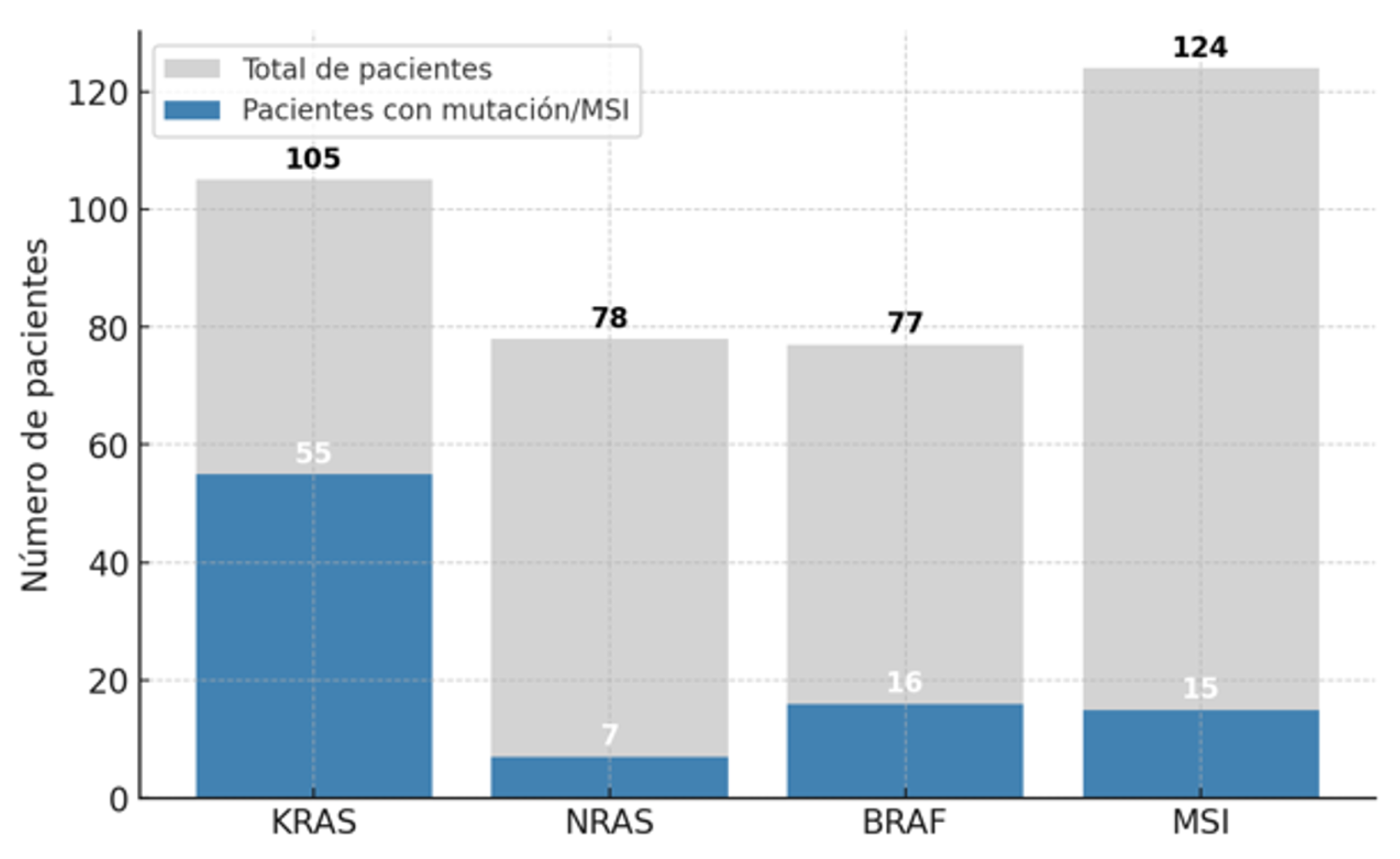

A descriptive analysis (n = 166;

Figure 2) of mutational frequency in sporadic colorectal cancer was conducted to explore the prognostic implications of

KRAS mutations and the

BRAF V600E mutation. Patients with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) or with tumors located in the middle or lower rectum were excluded. The mutational frequency was analyzed in cases for which at least partial molecular data were available. A larger number of patients had individual MSI testing results compared to the other molecular markers, with

KRAS testing being the next most frequent.

A descriptive statistical analysis was performed on 166 colorectal cancer (CRC) tumors. A high prevalence of KRAS mutations was observed (52.4%), highlighting its major role in colorectal tumorigenesis and its relevance in resistance to anti-EGFR therapies. The NRAS gene showed a low mutation rate (8.9%), consistent with its lower prevalence reported in the literature compared to KRAS. BRAF mutations were present in 22.1% of cases, a slightly higher proportion than typically described, potentially indicating a subgroup of patients with distinct clinical features, such as a greater association with MSI. Microsatellite instability was detected in 12.1% of tumors, a frequency consistent with expectations for sporadic colorectal cancer.

3.2 Comparative Study

However, the comparative analysis was conducted on those patients who met all the inclusion criteria, evaluating the association between each gene and the presence or absence of microsatellite instability.

3.2.1. KRAS and MSI Association

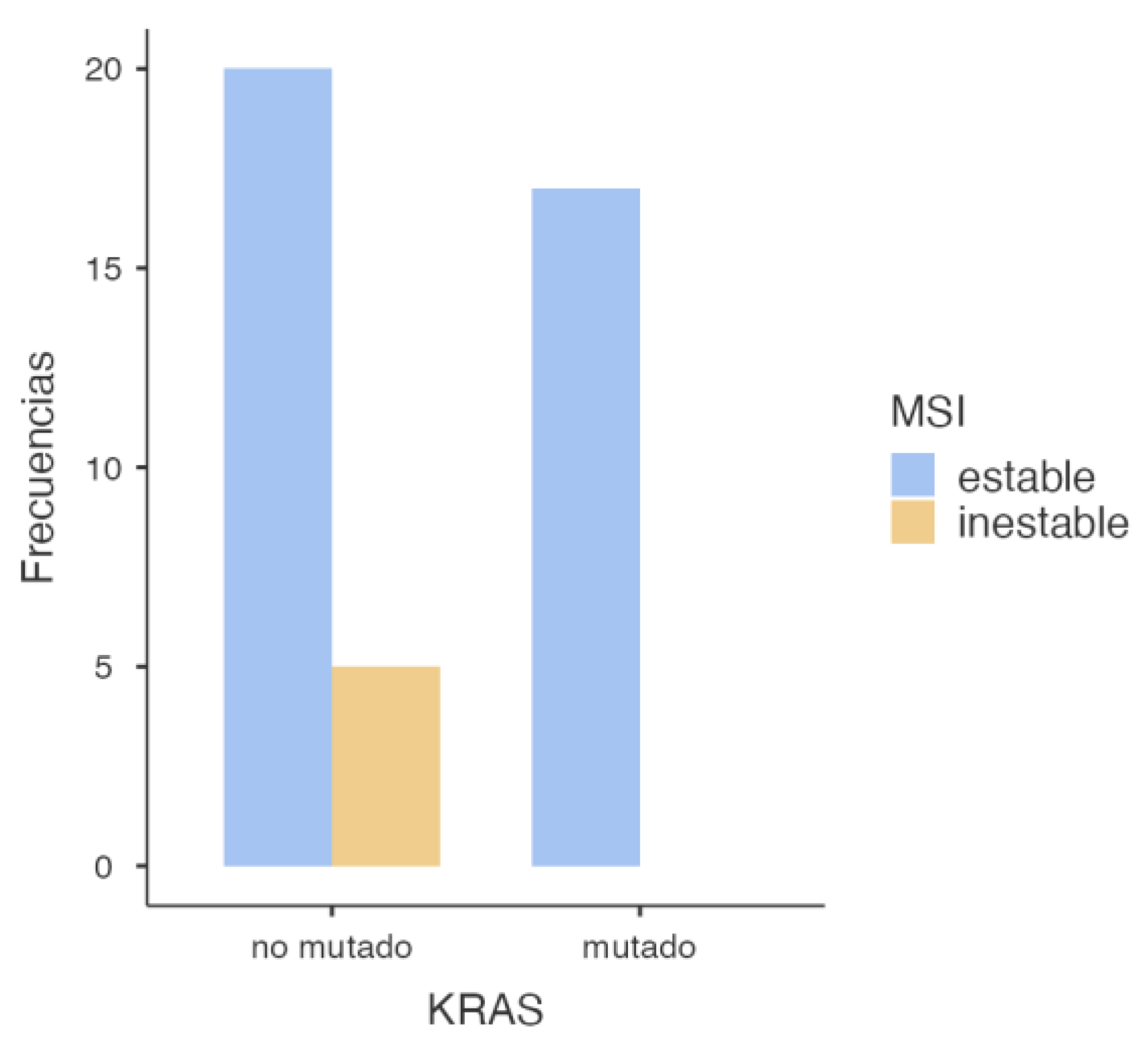

First, the association between

KRAS mutation and MSI status was assessed, yielding the following findings (

Figure 3).

The statistical analysis performed (

Table 1) revealed a significant association between KRAS mutations and microsatellite stability, with a p-value of 0.049 in the chi-square test. This suggests that tumors harboring

KRAS mutations are less likely to exhibit microsatellite instability (MSI). However, when applying Fisher’s exact test—more appropriate in contingency tables with small sample sizes—the p-value was 0.070. Although close to the conventional threshold of significance, this result does not allow for a definitive conclusion, and the observed association may be due to chance (

Table 2). Regarding the odds ratio analysis, an OR of 0.106 (95% CI: 0.00549–2.06) was observed, suggesting a lower probability of MSI in

KRAS-mutated tumors. Nevertheless, the wide confidence interval crossing the null value indicates substantial uncertainty and a non-conclusive association (

Table 3).

3.2.2. NRAS and MSI Association

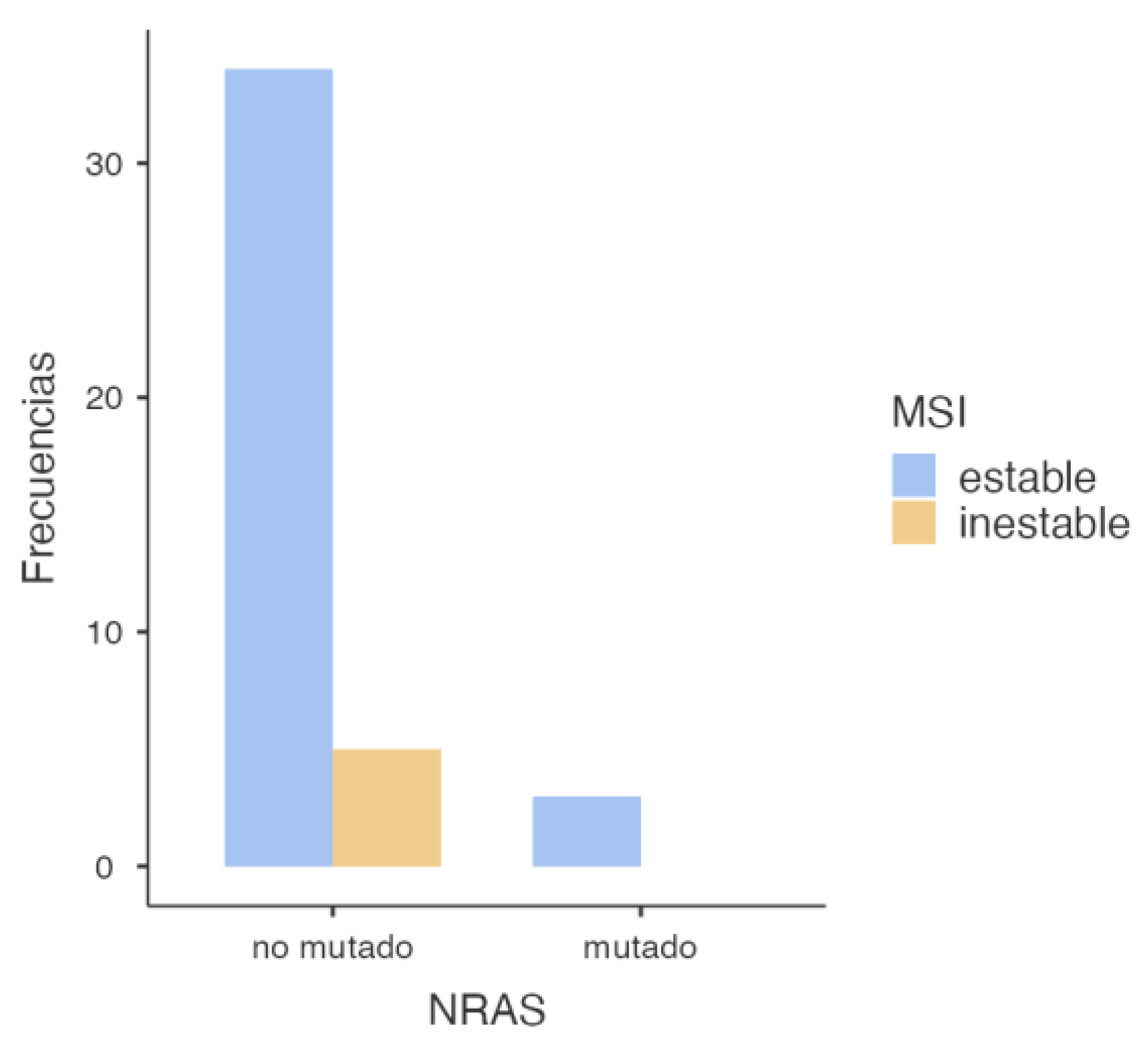

To evaluate the potential association between

NRAS mutations and mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency, a similar statistical analysis was conducted, yielding the following results (

Figure 4).

The chi-square test results for the association between

NRAS mutation status and microsatellite stability (

Table 4) showed no statistical significance, with a p-value of 0.509, far above the standard significance threshold (p < 0.05), precluding rejection of the null hypothesis. This implies no association between

NRAS mutation and microsatellite status. Supporting this finding, Fisher’s exact test yielded a p-value of 1.000, further reinforcing the absence of a statistically significant relationship (

Table 5). Moreover, the odds ratio was 0.896 (95% CI: 0.0405–19.8), a value very close to 1, indicating no appreciable association. The wide confidence interval that includes the null value again highlights the lack of statistical power and potential for random variation (

Table 6).

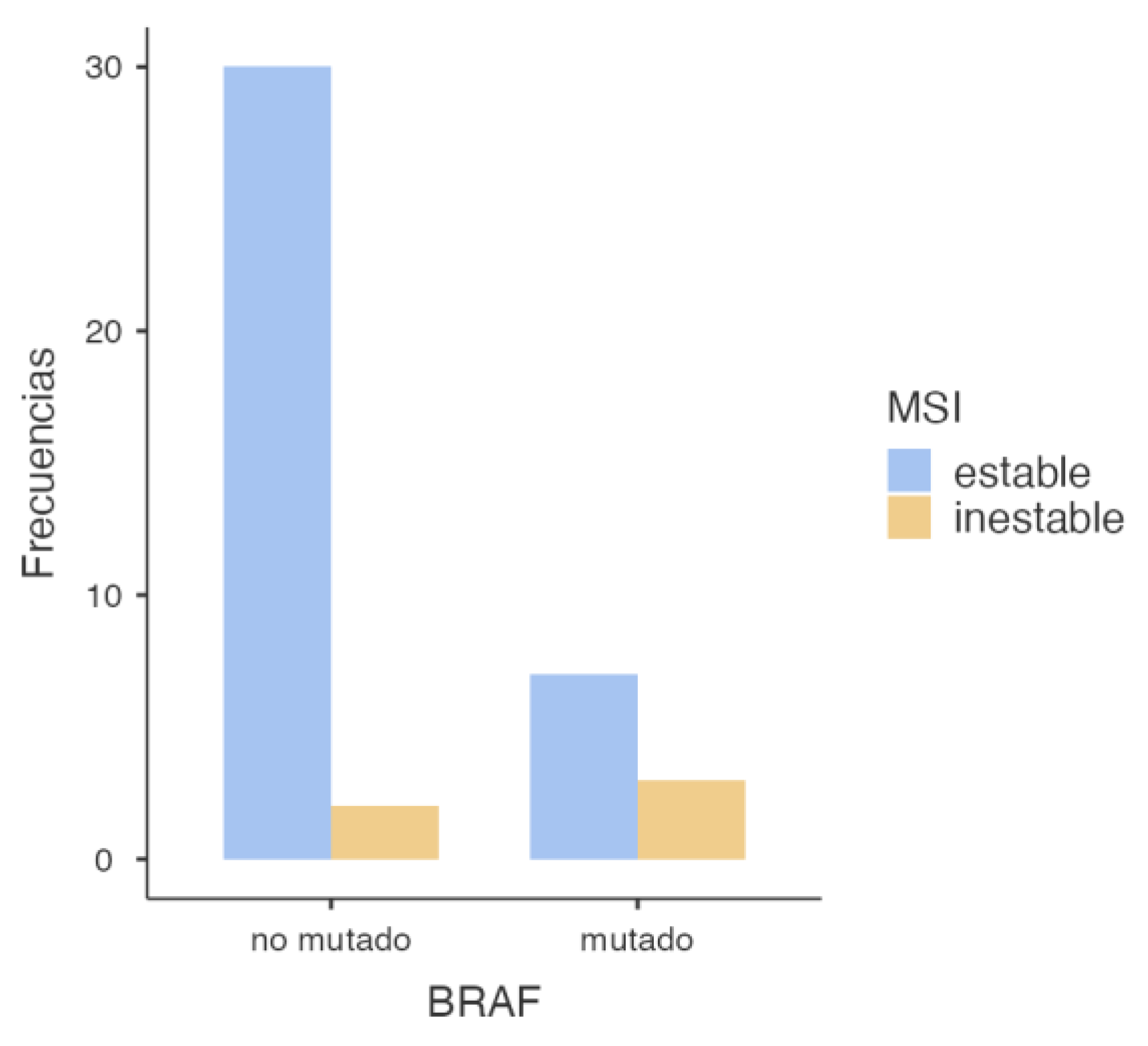

3.2.3. BRAF and MSI Association

Subsequently, the association between

BRAF mutation (specifically the V600E variant) and MSI status was assessed, and the following results were obtained (

Table 7 and

Figure 5).

The chi-square test showed a statistically significant association between BRAF mutations and MSI (p = 0.043), indicating that tumors harboring BRAF mutations are more likely to exhibit microsatellite instability. This suggests a potential biomarker role for BRAF in identifying MSI-positive tumors. However, Fisher’s exact test yielded a p-value of 0.078, which—although below 0.1—does not meet the conventional statistical significance threshold of 0.05 (Table 8). The odds ratio was 6.43 (95% CI: 0.897–46.1), suggesting a strong association between BRAF mutations and MSI. However, the wide confidence interval crossing 1 indicates a high degree of uncertainty, limiting the robustness of the conclusion. Nevertheless, the elevated OR suggests a potentially relevant trend that warrants confirmation in larger cohorts (Table 9).

Table 8.

Chi-Square Test Results

Table 8.

Chi-Square Test Results

| |

Value |

Gl |

p |

| X2

|

4.10 |

1 |

0.043 |

| Fisher’s Exact Test p-value |

|

|

0.078 |

| N |

42 |

|

|

Table 8.

Comparative Measures

Table 8.

Comparative Measures

| |

|

95% Confidence Intervals |

| |

Value |

Lower |

Upper |

| Odds Ratio |

6.43 |

0.897 |

46.1 |

| Relative Risk |

1.341

|

0.884 |

2.03 |

4. Discussion

Our findings support the role of KRAS as the most prevalent mutation in sporadic colorectal cancer (sCRC), particularly associated with microsatellite-stable (MSS) tumors, while BRAF-mutated tumors show a higher frequency of MSI, consistent with their recognized clinical relevance. The low frequency of NRAS mutations aligns with previous studies and does not appear to be associated with MSI.

The most relevant findings include a high prevalence of KRAS mutations (52.4%), a substantial proportion of BRAF V600E mutations (20.8%), and a low NRAS mutation rate (8.9%), consistent with previous literature. MSI was identified in 12.1% of cases, aligning with expected values in the context of sporadic colorectal cancer.

From a statistical perspective, a significant association was observed between KRAS mutations and MSS status (p = 0.049), suggesting that KRAS-mutated tumors tend to have a functional mismatch repair (MMR) system. This finding is consistent with previous studies linking KRAS mutations with MSS tumors and distinct molecular profiles from MSI phenotypes. Conversely, a significant association was identified between BRAF V600E mutations and MSI (p = 0.043), reinforcing BRAF’s role as a molecular marker of this tumor subtype. However, the small sample size and wide confidence intervals—such as the OR of 6.43 (95% CI: 0.897–46.1)—require cautious interpretation and further validation in larger studies. No significant association was found between NRAS mutations and MSI status (p = 0.509). The OR close to 1 (0.896) and the wide confidence interval crossing the null value suggest that NRAS mutations likely do not play a relevant role in the genomic instability of these tumors.

These findings are consistent with the results reported by Ye et al. (2015), who described a higher prevalence of KRAS mutations in MSS tumors, supporting the hypothesis that KRAS mutations are associated with a functional MMR system. Additionally, the low frequency of NRAS mutations in our cohort is in line with the same study, highlighting a more limited role for this gene in the tumorigenesis of sporadic colorectal cancer. The association between BRAF V600E mutations and the MSI phenotype has been widely reported in the literature. Specifically, studies by Birgisson et al. (2015) and Fan et al. (2021) demonstrated a strong association between BRAF mutations and MSI-positive tumors, in agreement with our findings. Moreover, Rasuck et al. (2012) emphasized the role of BRAF V600E in the context of genomic instability and MMR epigenetic alterations, underlining its value as a molecular and prognostic biomarker.

Despite the clinical and biological relevance of these findings, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the small sample size—particularly in the subgroup with complete molecular and MSI data (n = 42)—limits the statistical power of the analyses and affects the robustness of the detected associations. This is reflected in the Fisher's exact test results and the wide confidence intervals observed, indicating substantial variability in the estimates.

Additionally, the retrospective, single-center design may introduce selection bias. The lack of comprehensive clinical data in some cases—such as tumor stage, specific anatomical location, or treatment details—precluded a more detailed patient characterization and hindered the analysis of potential correlations between molecular profile and clinical behavior.

According to our decision model for gene testing, next-generation sequencing (NGS) proved to be superior to single-gene analysis techniques (real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry). Including additional relevant biomarkers—such as PIK3CA, NTRK alterations, or MMR-related epigenetic changes—could further refine the molecular profiling of tumors and enhance clinical decision-making in the 42 patients studied (

Figure 6).

Therefore, future studies should aim to expand the patient cohort through a prospective, multicenter design that integrates clinical, molecular, and outcome variables. Validation in independent populations would enhance the generalizability and applicability of these findings, laying the groundwork for a more personalized approach in the management of sporadic colorectal cancer.

5. Conclusions

Based on these data, we conclude that initial molecular analysis using comprehensive NGS panels is more efficient, saving time, tissue, and costs compared to stepwise single-gene testing. Moreover, this approach allows for more accurate molecular classification and facilitates the selection of targeted therapies and immunotherapy. In the absence of upfront NGS availability, we suggest starting with KRAS analysis, followed by BRAF and MSI testing in KRAS wild-type cases, thus promoting an efficient molecular classification strategy for CRC.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to my supervisor, Dr. Javier Azúa Romeo, whose guidance and dedication were essential throughout the development of this work. I would also like to thank the team at the laboratory Analiza, for their collaboration and support in the molecular analysis procedures and data interpretation. Lastly, I thank my peers and loved ones for their emotional support and encouragement during this process.

Author Contributions

The contribution of all authors was proportional and equitable, with no differences among them. The specific contribution of each is detailed below. Marta Rada Rodríguez: conceptualization, study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript drafting. Dr. Javier Azúa Romeo: technical supervision, pathological interpretation, and validation of findings. Bárbara Angulo Biedma: support in molecular analysis procedures and critical manuscript review. Irene Rodríguez Pérez: molecular data management and verification, assistance with biostatistical interpretation, and manuscript review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRC |

Colorectal Cancer |

| SCRC |

Sporadic Colorectal Cancer |

| MSI |

Microsatellite Inestability |

| MSS |

Microsatellite Stability |

| MMR |

Mismatch Repair |

| NGS |

Next Generation Sequencing |

| IHC |

Inmunohistochemical |

References

- Keshinro A, Ganesh K, Vanderbilt C, Firat C, Kim JK, Chen CT, et al. Characteristics of Mismatch Repair-Deficient Colon Cancer in Relation to Mismatch Repair Protein Loss, Hypermethylation Silencing, and Constitutional and Biallelic Somatic Mismatch Repair Gene Pathogenic Variants. Dis Colon Rectum. 2023;66(4):549–58.

- Orlandi E, Giuffrida M, Trubini S, Luzietti E, Ambroggi M, Anselmi E, et al. Unraveling the Interplay of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and Micro-Satellite Instability in Non-Metastatic Colon Cancer: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics. 2024;14(10). [CrossRef]

- Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, Liao X, Yamauchi M, Nishihara R, et al. Microsatellite instability and braf mutation testing in colorectal cancer prognostication. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(15):1151–6. [CrossRef]

- Birgisson H, Edlund K, Wallin U, Påhlman L, Kultima HG, Mayrhofer M, et al. Microsatellite instability and mutations in BRAF and KRAS are significant predictors of disseminated disease in colon cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez M, Monteagudo F, Rodríguez M, García G. Marcadores inmunohistoquímicos de inestabilidad microsatelital para latipificación del cáncer colorrectal. Aspectos claves para la interpretaciónpor el patólogo. 2022;23(4). Available from: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5149-2450.

- Fan JZ, Wang GF, Cheng X Bin, Dong ZH, Chen X, Deng YJ, et al. Relationship between mismatch repair protein, RAS, BRAF, PIK3CA gene expression and clinicopathological characteristics in elderly colorectal cancer patients. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(11):2458–68.

- Remonatto G, Ferreira Salles Pilar E, De-Paris F, Schaefer PG, Kliemann LM. Integrated molecular profiling of RAS, BRAF mutations, and mismatch repair status in advanced colorectal carcinoma: insights from gender and tumor laterality. J Gastrointest Oncol [Internet]. 2024 Aug 31;15(4):1580–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39279928. [CrossRef]

- Sinicrope FA. Evaluating the Combination of Microsatellite Instability and Mutation in BRAF as Prognostic Factors for Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(3):391–4. [CrossRef]

- Salem ME, Bodor JN, Puccini A, Xiu J, Goldberg RM, Grothey A, et al. Relationship between MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6 gene-specific alterations and tumor mutational burden in 1057 microsatellite instability-high solid tumors. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(10):2948–56.

- Parsons MT, Buchanan DD, Thompson B, Young JP, Spurdle AB. Correlation of tumour BRAF mutations and MLH1 methylation with germline mismatch repair (MMR) gene mutation status: a literature review assessing utility of tumour features for MMR variant classification. J Med Genet [Internet]. 2012 Mar;49(3):151–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22368298. [CrossRef]

- Bläker H, Alwers E, Arnold A, Herpel E, Tagscherer KE, Roth W, et al. The Association Between Mutations in BRAF and Colorectal Cancer-Specific Survival Depends on Microsatellite Status and Tumor Stage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2019 Feb;17(3):455-462.e6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29660527. [CrossRef]

- Kopetz S, Grothey A, Yaeger R, Van Cutsem E, Desai J, Yoshino T, et al. Encorafenib, Binimetinib, and Cetuximab in BRAF V600E-Mutated Colorectal Cancer. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2019 Oct 24;381(17):1632–43. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31566309.

- Ye JX, Liu Y, Qin Y, Zhong HH, Yi WN, Shi XY. KRAS and BRAF gene mutations and DNA mismatch repair status in Chinese colorectal carcinoma patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(5):1595–605.

- Rencuzogullari A, Bisgin A, Erdogan KE, Gumus S, Yalav O, Boga I, et al. Site specific genetic differences in colorectal cancer via Next-Generation-Sequencing using a multigene panel. Ann Ital Chir [Internet]. 2023;94:605–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38131395.

- Ashish S, Raj M. Importance of Early Next-Generation Sequencing in Microsatellite Unstable Colon Cancer With a High Tumor Mutation Burden. Cureus. 2022;2022(3):4–8. [CrossRef]

- Hernando-Calvo A, Nguyen P, Bedard PL, Chan KKW, Saleh RR, Weymann D, et al. Impact on costs and outcomes of multi-gene panel testing for advanced solid malignancies: a cost-consequence analysis using linked administrative data. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;69:1–12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).