1. Introduction

High-quality chemistry education is extremely important, and this requires chemistry teachers with an extensive knowledge of chemistry and a comprehensive understanding of chemistry as a science. Chemistry is a versatile and rapidly evolving science. It is a massive research field with one of the world's largest industrial sectors – the chemical industry supports over 120 million jobs worldwide [

1]. Chemical research is highly multidisciplinary, and chemistry is a key science in developing solutions to all major sustainability challenges, such as climate change, sustainable energy, clean water and a sufficient food supply for all people [

2]. Despite its high societal relevance and excellent employment opportunities, the field has a major challenge in that there is a massive shortage of skilled workforce [

3]. In other words, not enough students are studying chemistry.

The reason behind the lack of students is the result of two factors. The first issue is the lack of experienced relevance. Many scholars have reported that young people do not find chemistry interesting, or more precisely, relevant [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This affects the overall number of chemistry students, which has been a global concern for decades [

9]. Fortunately, the chemistry education research (CER) community is aware of the relevance challenge. In recent years, CER scholars have actively been developing novel evidence-based relevance-oriented learning materials as a solution to the challenge [

10,

11,

12,

13]. The second issue is the high dropout rate. In many parts of the world, more than 30% of chemistry undergraduate students fail to finish their degrees [

14,

15,

16]. Efforts to solve the dropout challenge have been made, for example, with enhanced student guidance [

17], strengthening the vocational relevance via career weeks [

18], and career-oriented inquiry-based activities [

19].

The current authors agree that it is important to support higher education chemistry studies by strengthening its vocational relevance. However, it does not solve the first challenge. According to research, an interest in science is created in childhood [

7,

20]. Therefore, we claim that the most efficient way to improve the situation is to train skilled and enthusiastic chemistry teachers. Chemistry teachers are the key stakeholders in introducing the potential of chemistry to young learners and to inspire them into chemistry careers [

21]. Therefore, high-quality chemistry teacher education (CTE) is the cornerstone of developing chemistry both as an academic and industrial field.

Future chemistry teachers are trained in tertiary education through academic study programs. The majority of chemistry teachers graduate from CTE or broader STEM teacher programs. Whatever the specific name, they are usually academic higher education degrees. Therefore, we argue that high-quality academic CTE needs to be evidence-based and research-oriented. At the University of Helsinki (Finland) we have been developing evidence-based CTE and training research-oriented chemistry teachers (ROCTs) for over 20 years [

22].

However, there is a constant need to develop and update the program because chemistry as a science is itself developing rapidly. For example, there have continuously been major advances in sustainable chemistry, modern technology, and material sciences. Future chemistry teachers need an up-to-date understanding of the field so that they can integrate contemporary science into their teaching. This is particularly important because chemistry in schools is being taught predominantly from a historical perspective [

23]. This does not seem to appeal to large numbers of learners, which leads to the main challenge in the field, namely that young people do not experience chemistry as relevant [

13]. Therefore, there is a special need to strengthen the vocational and societal relevance of chemistry education [

10,

12].

Based on this background, the aim of the article is to report on what kind of research-based development is constantly required to keep an academic higher education study program relevant and up-to-date. The aim is fulfilled by providing narrative insights by analyzing selected design-based research projects that our group has implemented in the past. We start by defining evidence-based CTE and continue by describing the characteristics of ROCTs (

Section 2). These are needed to understand the nature and requirements of evidence-based CTE. Then we introduce the applied research methodology (

Section 3) and report results (

Section 4). The article ends with conclusions and take-home messages (

Section 5).

2. Evidence-Based Chemistry Teacher Education

2.1. Definition of the Term “Evidence-Based”

We defined evidence-based CTE by reviewing several “evidence-based” educational terms and crafting a suitable concept for chemistry educational purposes. In the literature scholars have defined “evidence-based” from a content or educational research perspective. Ratcliffe et al. [

24] discuss “evidence-based practices” when they refer to the usage of educational research methods for ensuring efficient pedagogical practices. They identified the need for evidence-based teaching through focus-group interviews of educational experts, researchers, policymakers, and teachers. Toom and Husu [

25] use the term “research-based” for a similar context. They argue that a research-based orientation in tertiary teacher education is essential. It enables future teachers to engage and understand their teaching profession on a more comprehensive level. The matter is so crucial why the development of a teacher education should be based on systematic research strategy [

26].

Evidence-based practices encourage teachers to think like educational researchers. However, according to Valcke [

27], the “teacher as a researcher” analogy does not mean that the teacher professional should be an academic research position. It is more of a practice-oriented approach applying simple research settings to develop their own teaching and learning, taking an inquiry-based approach. For example, an iterative collaborative design approach could be taken to develop local level pedagogical models alongside peer teachers. The decision making could be supported with up-to-date scientific literature and researcher consultation through networks built up during university studies. The solutions developed could be validated using data gathered through observation and feedback questionnaires [

27].

In the context of CTE, the other building block of an evidence-based approach is chemical research. Therefore, in addition to the latest educational research insights, future chemistry teachers need to be able to include up-to-date chemical research in their teaching [

22]. This can often be challenging because teachers are not active chemistry researchers, and the current research topics may not be included in their studies or the latest research results will have come after their graduation [

23]. Fortunately, there are several ways of including contemporary research in the curriculum. Teachers can participate in in-service training events and courses to update their knowledge base and network [

28,

29,

30] or use recent learning materials developed by CER scholars in collaboration with researchers [

12]. For example, our research group developed laboratory activity on ionic liquids in cooperation with an organic chemistry research group from the University of Helsinki [

10].

2.2. Research-Oriented Chemistry Teacher

The aim of evidence-based CTE is to produce research-oriented chemistry teachers, i.e., ROCTs [

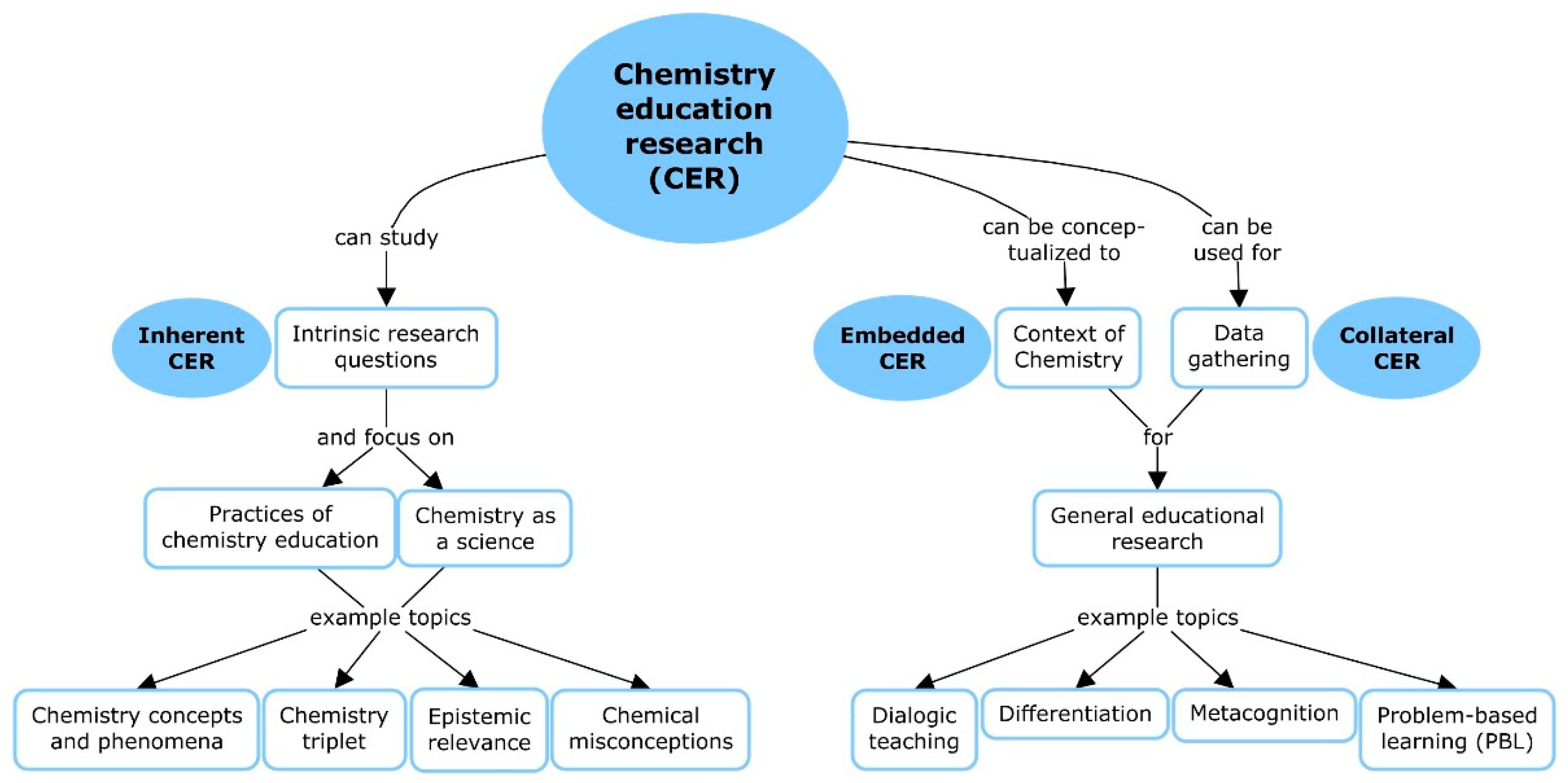

22]. It is important to realize that the research component of an ROCT is CER. According to Taber [

31], CER can be inherent, embedded or collateral (see

Figure 1). The inherent approach focuses on research questions arising from the practices of chemistry education and chemistry as a science. Embedded CER research has a general educational focus that has been conceptualized in the context of chemistry. Collateral CER is educational research where, for example, data has been collected in a chemistry learning context without subject-specific conceptual operationalization. The CER community has a strong consensus that the intrinsic approach is most important for the development of the research field [

31].

2.3. Required Knowledge Components

The ROCT’s expertise is built up from various knowledge areas. To illustrate the diversity of the required knowledge components, we use a technological pedagogical science knowledge (TPASK) framework for modelling them. TPASK is an application of a technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) framework designed especially for supporting the professional development of science teachers by integrating authentic research into the framework [

32]. TPACK is similar to TPASK, but it does not emphasize authentic science. TPACK is a general model focusing on content knowledge rather than scientific knowledge [

33].

TPASK can be visualized with a Venn diagram of technology, science, and pedagogy (see

Figure 2). The overlapping knowledge areas are technological science knowledge (TSK), technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) and pedagogical science knowledge (PSK) [

32].

By using the TPASK framework, we can illustrate the diversity of essential knowledge areas required of ROCTs:

PSK: The foundations of an ROCT’s expertise are good chemistry knowledge, excellent pedagogical skills and chemistry educational understanding of how these two are combined meaningfully [

34]. In addition, ROCTs care about their pupils’ and students’ learning. This knowledge is PSK because it combines chemistry and pedagogy [

32].

Science: ROCTs understand the nature of science (NOS) both in the context of chemistry and educational sciences. This means, e.g., that they understand how science works as an institution and how it is evaluated, how new information is produced and why, what the role of science is in society, sustainability and politics and how science is financed [

35]. This knowledge is purely science knowledge. Note that the emphasis is on science and not only content. In this regard, the TPASK framework enables a more comprehensive understanding of the required expertise than the TPACK model [

32,

33].

Pedagogy: ROCTs have curious minds and are interested in constantly learning new things [

22]. To fulfil their learning needs, ROCTs have good meta level skills, and they can evaluate continuous personal learning needs. ROCTs apply an inquiry-based approach to learning and engage with non-formal in-service learning resources and events [

29].

TSK, TPK, and Technology: Technology is integrated in everything. ROCTs need to master the usage of technology both in chemistry and education as well as in their chemistry educational interface. ROCTs follow the latest chemical, educational and chemistry educational research on both national and international levels. ROCTs are able to integrate contemporary science into the chemistry curriculum and their own teaching [

22]. From the TSK and PSK perspective, following the latest research is vital because chemistry is a data-driven rapidly developing instrumental science [

36]. Educational technology also takes huge leaps every year (see example [

37]).

TPASK: ROCTs can develop their teaching via educational research methods on a practical level and disseminate results along the appropriate channels. In the best scenario, research and development projects are conducted in collaboration with peers and members of the personal learning network [

25,

38].

2.4. Professional Identities

As mentioned, we aim to produce ROCTs that have two professional identities. We claim that chemistry teachers should consider themselves to be not only teachers but also chemists [

22]. Our previous research indicates that the current chemistry teacher education model effectively supports the development of teacher identity [

39]. However, the teacher identity is often so strong that we are currently developing the framework for specifically strengthening the chemist identity [

40].

Teachers’ professional identity, a complex construct of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that define them as educators, is crucial for teachers’ efficacy and adaptability [

41,

42]. Therefore, this is an essential issue to address in chemistry teacher education, especially from the perspective of the under-represented chemist identity. Our solution is to engage future chemistry teachers with contemporary chemical research in the CER courses offered. In this context, the location within the University of Helsinki Chemistry Department is crucial because this gives us direct access to chemistry scholars and their research groups. As members of the chemical research community, we are able to design our teaching to highlight the precise research focus of the Chemistry Department. The Department’s research areas are materials, energy, health, and environment and we approach these through our research group’s focus areas, which are sustainable chemistry and modern technology. In

Figure 3 we illustrate the interaction of different research focuses and their contribution to the ROCTs’ professional development.

We argue that engagement with contemporary science supports the relevance challenge. Learning from the latest chemical research and interacting with chemistry scholars develops future teachers’ understanding of relevance holistically. This will strengthen their chemist identity and improve their ability to include up-to-date chemical research in their teaching. Further, engaging young people more with contemporary science could be the solution to the relevance problem that the whole CER community has been seeking for over a decade [

13].

However, it should be noted that, before studying the subject, the teacher must encounter learners as people and create a good learning environment suitable for all. This is a well-known fact and applied in teacher education since the 1980’s [

34,

43]. In this regard, pedagogical skills are extremely important, even though content knowledge is the core knowledge that every chemistry teacher should master.

3. Methodology

This study is a qualitative research [

44]. We selected the qualitative approach to be able to produce in-depth descriptions of different kind of development needs that our CTE study program has had over the years. Descriptions are generated using narrative analysis used to analyse our past research projects [

45]. For the analysis we have selected different type of projects to illustrate the variance of the development needs. The examples are selected from recent projects to highlight current needs. The analysis is guided using the following research questions:

What kind of research resources and strategies are suitable for developing a CTE study program?

What kind of development needs and levels there are for ensuring the relevance of a CTE study program over time?

3.1. Narrative Analysis

Narrative analysis is a method to produce analytic accounts of narratives. Narratives are frameworks that help others to position their stories under an coherent body of knowledge [

45]. In this research we do not work with stories but on design needs, objectives or agendas. We have ensured the objectivity of the analysis by interpreting generated narratives thorough the theoretical framework presented in

Section 2. Theory-based analysis of narratives is mentioned important by Smith and Monforte in their methodological article of narrative analysis [

45].

Narrative analysis starts with deciding the data source or story [

45]. In our case we data sources are the selected research articles we published from research-based development of CTE. Next, we generated narratives by summarizing the key points of the selected research projects and reflecting them to the reviewed literature [

46].

3.2. Research Context: Current Degree Structure and Courses of the Developed CTE

In this section we describe research context including the degree structure and CER courses offered in the CTE under inspection. The aim for introducing the background is to support the validity and reliability of the qualitative research approach. This enables replication of the research design in other CTE contexts. Repeatability is an important reliability aspect for qualitative research [

44].

The CTE study program at the University of Helsinki has a standard European higher education degree structure. It comprises 300 ECTS credits, consisting of a BSc degree of 180 ECTS and an MSc degree of 120 ECTS (

Table 1). The Bachelor’s degree is planned as a three-year study track organized by the Faculty of Science. The Master’s degree is planned to take two years. It is also administered by the Faculty of Science, but a 60 ECTS portion of the MSc degree consists of pedagogical studies organized by the Faculty of Educational Sciences. Pedagogical studies include two teaching practice periods in the University of Helsinki Training Schools. Pedagogical studies are usually conducted in the fourth year. For their fifth and final year, the students return to the Faculty of Science and complete their CER Master’s thesis in the Department of Chemistry. The MSc degree includes at least 75 ECTS of CER studies, which means that at least 25% of the program is allocated to CER. This is important because CER studies are the only way to ensure a research-oriented approach in CTE.

To ensure constant engagement with CER studies, we have divided CER courses evenly through the study years. The curriculum has been iterated for over 20 years in 3 to 4-year curriculum cycles. Courses and course contents are developed and updated to match the current professional needs of chemistry teachers.

In the BSc studies we offer 5 CER courses, a thesis (6 ECTS) and seminar (1 ECTS), and a few general science education courses. At the Master’s level, there are 4 courses, a thesis (30 ECTS), and a CER research seminar (5 ECTS) (see

Table 2).

Research skills are at the core of CER expertise. We have designed a course that focuses on methodological issues as well as integrating different skills into every CER course. Research skills range from simple tasks, such as information retrieval and essay writing, to more complex skills, such as case study and design-based research (DBR). The specialized CER course is optional for Master’s students but mandatory for PhD students.

4. Results

4.1. Research Resources and Strategies (RQ1)

Because science is progressing, we need to update and re-develop our study program constantly. As mentioned, we use DBR as a research approach to ensure that development is based on research. DBR is a research-based development strategy designed to build educational artefacts such learning materials, pedagogical models and courses [

47,

48,

49]. It was originally developed in the 90’s and was initially called design experiments [

50]. Then in the last 30 years the methodology has evolved and currently DBR or educational design research (EDR) studies are a widely adopted research strategy used broadly in the educational field [

48]. We follow Edelson’s DBR model where the design process is conducted through empirical and theoretical problem analyses. The approach produces both practical artefacts that are called design solutions that can be used as platform for empirical studies to generate insights and theories [

47]. The methodology is constantly developing but it is important projects are based on authentic needs and design is decisions are validated through empirical studies and grounded to relevant theoretical framework [

51]. Recent advances in the field emphasizes the collaborative nature of the design projects, why we use a co-design model [

38,

52]. Co-design is essential because developing up-to-date courses and learning activities require expertise from multiple stakeholders such as chemistry researchers and educational experts. Also, the needs of the end users (teachers and learners) must be included in the need analysis to produce usable solutions.

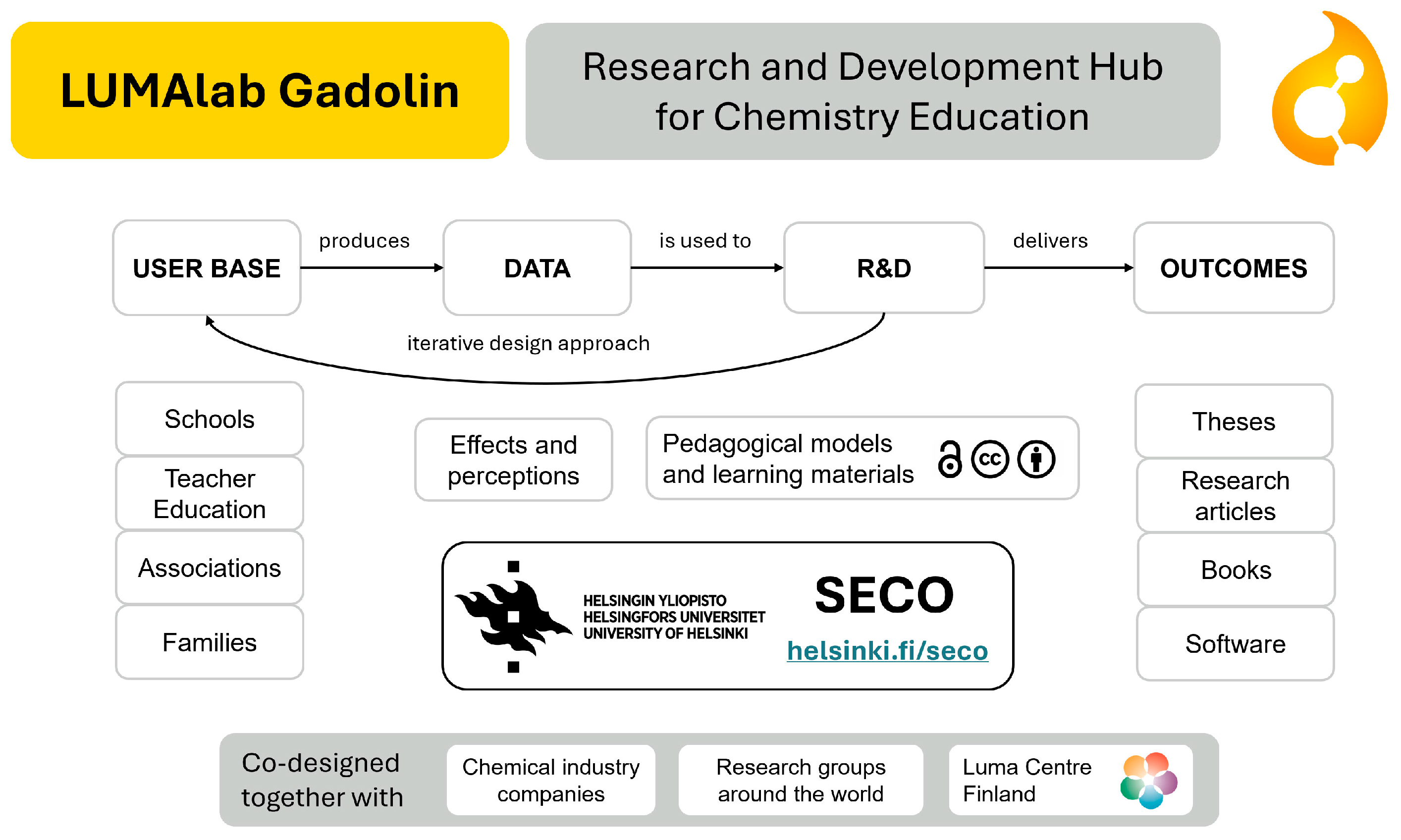

Over the years we realized that we need a research environment to conduct DBR projects efficiently. Therefore, we build a research and development (R&D) platform called LUMAlab Gadolin [

53]. It is a non-formal learning environment co-designed by our research group (SECO), research groups from the Department, chemical industry companies and LUMA Centre Finland

1 (see

Figure 4).

Our research group develops novel solutions for supporting the relevance of chemistry education. For example, we explore new technology and craft it into the chemistry educational context [

37,

55] or we develop new learning materials in collaboration with chemistry research groups [

10]. Much of the research is done with international collaboration [

11,

28,

56]. Through the DBR approach, the learning materials developed can be used to explore their effect on experienced relevance [

57]. Every year more than 4 000 learners and teachers make non-formal study visits to Gadolin and we use this for data gathering.

To support the development of research skills of ROCTs, LUMAlab Gadolin is integrated into every CTE course that we offer [

39]. Through Gadolin, future chemistry teachers learn how to teach in a laboratory and how to develop inquiry-based learning materials. This increases the professional relevance of our CTE program [

39]. During the last 15 years we have collected data for over 100 Master’s theses, 15 PhD dissertations and dozens of research articles.

4.2. Development Needs and Levels (RQ2)

Next, we answer the RQ2 by describing different levels of development needs. The levels and needs are reported via narratives that represent authentic research projects conducted in developing the CTE study program.

4.2.1. Level 1: Learning Resources for Courses

Modern technology is one focus area of our research group. In the past, we have worked with molecular modelling [

29] and microcomputer-based-laboratories [

58], but recently we have been focusing on educational cheminformatics [

56]. Since new technologies are developed and published constantly, we need to iterate technologies integrated in the courses in rapid cycles to offer up-to-date education. For example, a few years ago 3D printing was growing in the CER field. In collaboration with an analytical research group from the Department, we conducted a systematic literature review of the possibilities that it offers for chemistry education [

55]. Based on this review, we have designed learning activities that are included in one of the CER courses. LUMAlab Gadolin offers state-of-the-art laboratory equipment needed to impel the developed activities [

59]. Last yes, we made research on generative chatbot tools and designed activities that teach future chemistry teachers how to use them. TPACK models was used in grounding the activities to a suitable theoretical framework [

37].

From another perspective, we can use the guests who make study visits to Gadolin to explore the relevance of our crafted technology. For example, in one study we developed molecular modelling activities for lower-secondary education, and the pupils we studied perceived relevance after engaging with the activity. LUMAlab Gadolin enabled the collection of a quantitative sample size. This research started as a Master’s thesis and led to a full research article [

57].

4.2.2. Level 2: Pedagogical Models and Courses

Another focus area of our research group is sustainable chemistry. As an example, we describe an ongoing PhD project that aims to develop a pedagogical model of how to teach systems thinking in the context of sustainable chemistry. We started a course called “Sustainable Chemistry” that is a mandatory Bachelor’s level course offered future chemistry teachers. After a few courses, we noticed that systems thinking is one of the key competences that should be included in the course. To ensure research-based development we started a PhD project around it.

First, a PhD researcher conducted a problem analysis on how sustainability development competences are taught in universities throughout Finland [

60]. Based on the knowledge acquired, we developed a pedagogical model that was integrated into the course. The model uses authentic sustainable chemistry contexts retrieved from scholars working in the Department or in chemical industry companies. The chemists' perceptions ensured an evidence-based background [

61]. Next, the model was tested empirically in the course. We are currently working on reporting the results of the empirical phase. In this research project, LUMAlab Gadolin served as the communication platform between our research group, scholars from the Department and industry.

4.2.3. Level 3: Program and University Level Development

As described in the Research Context section 3.2, the CTE program of the University of Helsinki is conducted as a collaboration between two Faculties and four Departments. Because of multiple stakeholders participating in the teaching, it is important to ensure coherence in the study program. In this context, it means that courses and study units are designed to build upon the previous knowledge and all courses contribute to the overall objectives set for the program [

25]. In the University of Helsinki we support coherence between different Departments and Faculties through a co-design approach maintained by continuous communication and regular meetings [

38].

Through our research program we have built a strong relation between chemistry, chemistry education and pedagogy courses and the latest research conducted in these fields. Note that this model has been considered one of the explanatory factors in Finland's high PISA rankings earlier. It is crucial that STEM teachers acquire pedagogical knowledge and skills, acquire extensive knowledge of the scientific fields they teach and the nature of scientific knowledge [

62].

4.2.4. Level 4: National and International Level Development

The largest scale of the research-based development our CTE is engaged in focuses on improving the state of science education both in Finland and internationally. This also requires the largest networks and well planned co-design projects [

38]. Within Finland, we contribute to the development of STEM education as part of the national LUMA Centre Finland. The LUMA Centre actively applies for national and international funding that enable efficient project lifecycle [

54].

In addition to LUMA projects, our research group also collaborates directly with other CER groups via international R&D projects. For example, Chemical Safety in Science Education (CheSSE) is an ongoing ERASMUS+ project where we develop an educational online resource repository of chemical safety for science teachers and educational decisions makers across Europe. The repository is developed in collaboration with several universities and schools. To promote maximum dissemination materials are published in five languages (EN, FI, SL, SV and NO) [

63].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Earlier research recommends that academic study programs should base on systematic research and development [

25,

26,

64]. Also, all teaching is based on research. This means that teachers teach topics they focus on in their research, or teaching is based on current research knowledge [

26]. In chemistry teacher education, this requires current research in both chemistry and chemistry education [

49].

We agree with these recommendations. For example, in the CTE field research strategies can be designed to support the lack of relevance [

13,

65] via vocational, societal, technological or sustainable contexts [

12,

61]. Whatever is the focus, in CTE contexts it is recommended to emphasize inherent CER perspective [

31].

Often design contexts require multidisciplinary expertise. Therefore, it seems that collaborative DBR is a valid research approach to develop or update a higher education study program [

38,

52]. To summarize an answer to RQ1, we recommend that CER groups should design a systematic research program and consider building a similar research infrastructure that our LUMAlab Gadolin is for us. Onsite R&D hub offers many possibilities such as access to constant research participants [

53], and a platform to co-design and test new pedagogical inventions [

10,

37]. In addition, we can use the hub as an learning environment for teacher education and support the development of professional identities [

39].

To answer RQ2, our initial analysis indicated that we develop the CTE program at four levels simultaneously. The design perspective is shifting from internal to external as the levels rise.

- 1)

Learning Resources for Courses: BSc, MSc and small projects focus on learning activities, materials and exercises. On this level the perspective is usually internal, focusing on developing resources to be integrated into the CER courses. Note that micro-level activities should be designed to support the development of skills in argumentation and evidence-based decision-making [

26]. Especially in the learning resource development frameworks such as TPASK and TPACK are practical tools for ensuring that content knowledge, pedagogical aspects and selected technology are well aligned with each other [

32,

33,

37,

55].

- 2)

Pedagogical Models and Courses: PhD dissertations focus on developing larger learning modules or whole courses [

60,

61]. It is important to keep in mind that ROCTs need to learn academic research skills, such as qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research [

26]. Additionally, in chemistry teacher education, students must practice conducting chemistry research to learn about chemistry as a scientific discipline [

22,

35]. This is also mandatory for ROCTs.

- 3)

Program and University Level Development: Research projects can be used also at levels 1–2 but are especially needed in the CTE program and university level development. To ensure the coherence of a joint program level 3 requires faculty level collaboration inside the university.

- 4)

National and International Level Development: The fourth level is an interaction interface between the program and society. Level 4 focuses on improving science education at the national and international levels, which requires collaboration networks and external funding [

54,

63]. In general, the need for external funding starts from level 2.

See

Table 3 for the overall summary of the different DBR levels. More detailed descriptions of the approach and multiple design examples can be found from references [

38,

49].

Overall, this narrative analysis emphasizes the importance of evidence-based CTE in producing research-oriented chemistry teachers. It is necessary because a chemistry teacher is an academic professional who must be able to justify pedagogical decisions based on the latest research insights [

25,

40].

Everyone working in CTE should realize that chemistry teachers have two professional identities, i.e., they are both chemists and teachers [

22]. Given the importance of professional identities, this must be addressed in the CTE curriculum. Our suggestion is to engage future chemistry teachers with non-formal learning activities throughout their studies to maximize vocational relevance, and to foster interaction with the latest chemical research and scholars [

39]. In addition, continuous learning must be supported. To avoid the overemphasis of historical approach, chemistry teachers must be able to follow both chemical and educational research during their career [

23].

Finally, the most important point is to ensure the development of CER skills. CER is the competence that binds together the domains of chemical and educational knowledge. It is at the core of high-quality chemistry education [

31]. In our CTE program the development of CER skills is supported by integrating some skills in every CER course. According to our research and over 20 years of CTE experience, we are convinced that it is important to train research-oriented chemistry teachers. They are the key stakeholders in engaging young people in chemistry and solving the urgent challenge of relevance [

21].

In this article we described an evidence-based research-oriented chemistry teacher education model. Also, we focused on producing narrative insights into what kind of resources and R&D activities it takes to keep a CTE study program relevant in the rapidly developing world. We hope that the model can serve as a valuable example for local research-based CTE development around the world. For our program the need for further development is constant. Next, we will start a level 2 research project on what kind of CER future chemistry teachers conduct in their theses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., O.H. and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.; writing—review and editing, J.P., O.H. and M.A.; visualization, J.P.; project administration, J.P.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oxford Economics. The Global Chemical Industry: Catalyzing Growth and Addressing Our World’s Sustainability Challenges; International Council of Chemical Associations (ICCA): Washington, DC, 2019; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Fan, Y.V.; Lei, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Cao, Z. Towards Decoupling in Chemical Industry: Input Substitution Impacted by Technological Progress. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightcast. The Future Chemistry Workforce and Educational Pathways: Examining the Data behind the Changing Nature of Jobs and Skills in Chemistry; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, 2023; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Aalsvoort, J.V. Activity Theory as a Tool to Address the Problem of Chemistry’s Lack of Relevance in Secondary School Chemical Education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2004, 26, 1635–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, M.; Eilks, I. Increasing Student Motivation and the Perception of Chemistry’s Relevance in the Classroom by Learning about Tattooing from a Chemical and Societal View. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2014, 15, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N.Y.B.M.; Yueying, O. Evaluating the Relevance of the Chemistry Curriculum to the Workplace: Keeping Tertiary Education Relevant. J. Chem. Educ. 2017, 94, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J.; Dillon, J. Science Education in Europe: Critical Reflections, Report to the Nuffield Foundation; King’s College London: London, 2008; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lavonen, J.; Juuti, K.; Uitto, A.; Meisalo, V.; Byman, R. Attractiveness of Science Education in the Finnish Comprehensive School. In Research findings on young people’s perceptions of technology and science education; Technology Industries of Finland: Helsinki, 2005; pp. 5–30. ISBN 951-817-886-0. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, L.; Francis, B.; Moote, J.; Watson, E.; Henderson, M.; Holmegaard, H.; MacLeod, E. Reasons for Not/Choosing Chemistry: Why Advanced Level Chemistry Students in England Do/Not Pursue Chemistry Undergraduate Degrees. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2023, 60, 978–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernaa, J.; Kämppi, V.; Aksela, M. Supporting the Relevance of Chemistry Education through Sustainable Ionic Liquids Context: A Research-Based Design Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Jensen, L.; Rodríguez-Becerra, J.; Jorquera-Moreno, B.; Escudey, M.; Druker-Ibañez, S.; Hernández-Ramos, J.; Díaz-Arce, T.; Pernaa, J.; Aksela, M. Learning Reaction Kinetics through Sustainable Chemistry of Herbicides: A Case Study of Preservice Chemistry Teachers’ Perceptions of Problem-Based Technology Enhanced Learning. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilks, I.; Marks, R.; Stuckey, M. Socio-Scientific Issues as Contexts for Relevant Education and a Case on Tattooing in Chemistry Teaching. Educ. Quím. 2018, 29, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Relevant Chemistry Education: From Theory to Practice; Eilks, I., Hofstein, A., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, 2015; ISBN 978-94-6300-175-5. [Google Scholar]

- Heublein, U.; Schmelzer, R. Die Entwicklung der Studienabbruchquoten an den deutschen Hochschulen - Berechnungen auf Basis des Absolventenjahrgangs 2016 (Eng. The development of dropout rates at German universities - calculations based on the graduate year 2016); DZHW-Projektbericht; Deutsches Zentrum für Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsforschung (DZHW): Hannover, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Astin, A.W.; Astin, H.S. Undergraduate Science Education: The Impact of Different College Environments on the Educational Pipeline in the Sciences; Higher Education Research Institute, Graduate School of Education, University of California: Los Angeles, 1992; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Hailikari, T.K.; Nevgi, A. How to Diagnose At-Risk Students in Chemistry: The Case of Prior Knowledge Assessment. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2010, 32, 2079–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valto, P.; Nuora, P. The Role of Guidance in Student Engagement with Chemistry Studies. LUMAT Int. J. Math Sci. Technol. Educ. 2019, 7, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopegedera, A.M.R.P. STEMming the Tide: Using Career Week Activities To Recruit Future Chemists. J. Chem. Educ. 2005, 82, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.A.; Monterola, S.L.C.; Punzalan, A.E. Career-Oriented Performance Tasks: Effects on Students’ Interest in Chemistry. Asia-Pac. Forum Sci. Learn. Teach. 2013, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J.; Simon, S.; Collins, S. Attitudes towards Science: A Review of the Literature and Its Implications. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2003, 25, 1049–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avargil, S.; Shwartz-Asher, D.; Reiss, S.R.; Dori, Y.J. Professors’ Retrospective Views on Chemistry Career Choices with a Focus on Gender and Academic Stage Aspects. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 36, 101249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksela, M. Evidence-Based Teacher Education: Becoming a Lifelong Research-Oriented Chemistry Teacher? Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2010, 11, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonder, R.; Mamlok-Naaman, R. Teaching Chemistry through Contemporary Research versus Using a Historical Approach. Chem. Teach. Int. 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, M.; Bartholomew, H.; Hames, V.; Hind, A.; Leach, J.; Millar, R.; Osborne, J. Evidence-based Practice in Science Education: The Researcher–User Interface. Res. Pap. Educ. 2005, 20, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toom, A.; Husu, J. Research-Based Teacher Education Curriculum Supporting Student Teacher Learning. In Coherence in European Teacher Education; Doetjes, G., Domovic, V., Mikkilä-Erdmann, M., Zaki, K., Eds.; Springer Nature Ltd., 2024; pp. 173–188. ISBN 978-3-658-43720-6. [Google Scholar]

- Toom, A.; Kynäslahti, H.; Krokfors, L.; Jyrhämä, R.; Byman, R.; Stenberg, K.; Maaranen, K.; Kansanen, P. Experiences of a Research-Based Approach to Teacher Education: Suggestions for Future Policies. Eur. J. Educ. 2010, 45, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcke, M. “Evidence-Based Teaching, Evidence-Based Teacher Education” (Quality of Teachers and

Quality of Teacher Education). In Preparing Teachers for the 21st Century; Zhu, X., Zeichner, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 53–66. ISBN 978-3-642-36970-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Ramos, J.; Rodríguez-Becerra, J.; Cáceres-Jensen, L.; Aksela, M. Constructing a Novel E-Learning Course, Educational Computational Chemistry through Instructional Design Approach in the TPASK Framework. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksela, M.; Lundell, J. Computer-Based Molecular Modelling: Finnish School Teachers’ Experiences and Views. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2008, 9, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copriady, J.; Zulnaidi, H.; Alimin, M.; Albeta, S.W. In-Service Training and Teaching Resource Proficiency amongst Chemistry Teachers: The Mediating Role of Teacher Collaboration. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taber, K.S. Identifying Research Foci to Progress Chemistry Education as a Field. Educ. Quím. 2018, 28, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoyiannis, A. Designing and Implementing an Integrated Technological Pedagogical Science Knowledge Framework for Science Teachers Professional Development. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M.; Mishra, P. What Is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)? Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 2009, 9, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erduran, S.; Dagher, Z.R.; McDonald, C.V. Contributions of the Family Resemblance Approach to Nature of Science in Science Education. Sci. Educ. 2019, 28, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferk Savec, V. The Opportunities and Challenges for ICT in Science Education. LUMAT Int. J. Math Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 5, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernaa, J.; Ikävalko, T.; Takala, A.; Vuorio, E.; Pesonen, R.; Haatainen, O. Artificial Intelligence Chatbots in Chemical Information Seeking: Narrative Educational Insights via a SWOT Analysis. Informatics 2024, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksela, M. Towards Student-Centred Solutions and Pedagogical Innovations in Science Education through Co-Design Approach within Design-Based Research. LUMAT Int. J. Math Sci. Technol. Educ. 2019, 7, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haatainen, O.; Pernaa, J.; Pesonen, R.; Halonen, J.; Aksela, M. Supporting the Teacher Identity of Pre-Service Science Teachers through Working at a Non-Formal STEM Learning Laboratory. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erduran, S.; Kaya, E. Towards Development of Epistemic Identity in Chemistry Teacher Education. In Transforming Teacher Education Through the Epistemic Core of Chemistry; Science: Philosophy, History and Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 169–189. ISBN 978-3-030-15325-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Y.; Tripp, J.; Liu, X. Science Teacher Identity Research: A Scoping Literature Review. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2024, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijaard, D.; Meijer, P.C.; Verloop, N. Reconsidering Research on Teachers’ Professional Identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2004, 20, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, J.; Sarajärvi, A. Laadullinen tutkimus ja sisällönanalyysi; Uudistettu laitos.; Tammi: Helsinki, 2018; ISBN 978-951-31-9953-1. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.; Monforte, J. Stories, New Materialism and Pluralism: Understanding, Practising and Pushing the Boundaries of Narrative Analysis. Methods Psychol. 2020, 2, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. Writing Narrative Style Literature Reviews. Med. Writ. 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelson, D.C. Design Research: What We Learn When We Engage in Design. J. Learn. Sci. 2002, 11, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Shattuck, J. Design-Based Research A Decade of Progress in Education Research? Educ. Res. 2012, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernaa, J.; Aksela, M. Model-Based Design Research: A Practical Method for Educational Innovations. Adv. Bus.-Relat. Sci. Res. J. 2013, 4, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. Design Experiments: Theoretical and Methodological Challenges in Creating Complex Interventions in Classroom Settings. J. Learn. Sci. 1992, 2, 141–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juuti, K.; Lavonen, J. Design-Based Research in Science Education: One Step Towards Methodology. Nord. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2006, 2, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostøl, K.B.; Remmen, K.B.; Braathen, A.; Stromholt, S. Co-Designing Cross-Setting Activities in a Nationwide STEM Partnership Program – Teachers’ and Students’ Experiences. LUMAT Int. J. Math Sci. Technol. Educ. 2021, 9, 426–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

ChemistryLab Gadolin: 15 Years of Inspiring Innovations for Science Education; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, 2024; ISBN 978-952-84-0098-1.

-

LUMA Finland -Together We Are More; LUMA Centre Finland: University of Helsinki, 2020; ISBN 978-951-51-6934-1.

- Pernaa, J.; Wiedmer, S. A Systematic Review of 3D Printing in Chemistry Education – Analysis of Earlier Research and Educational Use through Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge Framework. Chem. Teach. Int. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernaa, J.; Takala, A.; Ciftci, V.; Hernández-Ramos, J.; Cáceres-Jensen, L.; Rodríguez-Becerra, J. Open-Source Software Development in Cheminformatics: A Qualitative Analysis of Rationales. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernaa, J.; Kiviluoto, O.M.O.; Aksela, M. The Relevance of Computer-Based Molecular Modeling and the Effect of Interest: A Survey of Finnish Lower-Secondary Education Pupils’ Perceptions. In Ainedidaktiikka ajassa; Routarinne, S., Heinonen, P., Kärki, T., Rönkkö, M.-L., Korkeaniemi, A., Eds.; Ainedidaktisia tutkimuksia; Turun yliopisto, Kasvatustieteiden tiedekunta, Opettajankoulutuslaitos, Rauman kampus: Rauma, 2023; pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aksela, M.K. Engaging Students for Meaningful Chemistry Learning through Microcomputer-Based Laboratory (MBL) Inquiry. Educ. Quím. EduQ 2011, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernaa, J. Possibilities and Challenges of Using Educational Cheminformatics for STEM Education: A SWOT Analysis of a Molecular Visualization Engineering Project. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, E.; Pernaa, J.; Aksela, M. Promoting Sustainable Development Competencies and Teaching in Chemistry Education at University. FMSERA J. 2021, 4, 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- Vuorio, E.; Pernaa, J.; Aksela, M. Lessons for Sustainable Science Education: A Study on Chemists’ Use of Systems Thinking across Ecological, Economic, and Social Domains. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välijärvi, J.; Kupari, P.; Linnakylä, P.; Reinikainen, P.; Sulkunen, S.; Törnroos, J.; Arffman, I. The Finnish Success in Pisa – and Some Reasons behind It : 2 Pisa 2003; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, 2007; ISBN 978-951-39-3038-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tveit, S.; Faegri, K. A New Online Resource for Chemical Safety and Green Chemistry in Science Education. Chem. Teach. Int. 2023, 5, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toom, A.; Krokfors, L.; Kynäslahti, H.; Stenberg, K.; Maaranen, K.; Jyrhämä, R.; Byman, R.; Kansanen, P. Exploring the Essential Characteristics of Research-Based Teacher Education from the Viewpoint of Teacher Educators: Annual Teacher Education Policy in Europe Network (TEPE) Conference. Proc. Second Annu. Teach. Educ. Policy Eur. Netw. TEPE Conf. 2008, 166–179. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey, M.; Hofstein, A.; Mamlok-Naaman, R.; Eilks, I. The Meaning of ‘Relevance’ in Science Education and Its Implications for the Science Curriculum. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2013, 49, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

LUMA Centre Finland is a science and math education network of Finnish universities. LUMA is an acronym referring to Finnish words science (luonnontieteet) and mathematics (matematiikka) [ 54]. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).