Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Background: Systemic racism in Canadian healthcare is deep-rooted, generating inequities in workforce diversity and patient care. Black, racialized, and Indigenous communities encounter heightened barriers to accessing medical care and career advancement due to institutionally rooted biases. Despite Canada’s single-payer, universally accessible care, studies have documented widespread inequities in access, care, and health outcomes. The exclusion of foreign-trained healthcare professionals who benefited from the Canadian Immigration Point-Based Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS) from the labor force further entrenches inequities, mirroring systemic biases [14]. Addressing these issues is crucial for ensuring equitable healthcare delivery. Objective: This narrative review critically assesses systemic racism in Canadian healthcare, with consideration for racial inequality in patient care, career barriers for racialized healthcare professionals, and institution policies with a discriminatory intention. It identifies the structural barriers that preserve inequity and proposes policy-guided recommendations for systemic reform. Methods: This narrative review synthesizes empirical research, government reports, and case studies to examine systemic racism in Canadian healthcare. Sources were selected based on relevance, credibility, and publication within the last 15 years. Inclusion criteria focused on studies examining racial disparities in healthcare access, professional barriers, and policy interventions. Case studies were chosen based on their legal and policy significance, particularly those highlighting systemic failures leading to patient harm. Thematic analysis was used to categorize key issues, ensuring a comprehensive policy-driven discussion. Results: The review identifies three primary systemic barriers: 1. Racial biases in patient care lead to delayed treatment, misdiagnoses, and higher mortality rates among Black and Indigenous patients. 2. Institutional racism in healthcare workforce structures restricts opportunities for racialized healthcare professionals, limiting diversity in medical leadership. 3. Credentialing barriers disproportionately affect internationally trained physicians (ITPs), preventing them from contributing to Canada’s overburdened healthcare system. Case studies highlight the severe consequences of healthcare discrimination. Brian Sinclair, an Indigenous man, died after being ignored for 34 hours in a Winnipeg ER. Joyce Echaquan, an Atikamekw woman, live-streamed racist abuse from nurses before her death. These cases underscore the urgent need for systemic policy reforms to prevent further medical neglect. Conclusion: Several evidence-based policy interventions are necessary to dismantle racism in Canadian healthcare. Some of these interventions include mandatory anti-racism and cultural competency training for Healthcare professionals, the collection of race-based health data to track disparities and inform policies, and fair credentialing processes for international medical school graduates to address workforce shortages. Independent accountability and review processes must also be established to prevent medical abuse. By taking such actions, a fairer, accessible, and effective system will ensure that racialized communities receive the care they deserve. [M1]References should be numbered in order of appearance. Please rearrange all the references to appear in numerical order.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of Systemic Racism in Healthcare

Defining Systemic Racism and Its Expressions in Healthcare

Historical Injustices in Healthcare for Indigenous and Black Communities

Disparities in Access to Care, Health Outcomes, and Workforce Representation

1.2. Justification for the Review

The Urgency of Addressing Systemic Racism in Canadian Healthcare

Research Gaps in Health Disparities and Healthcare Worker Diversity

1.3. Objectives of the Review

-

Discuss Healthcare Disparities in Black and Indigenous Communities

-

Analyze Workforce Challenges for Internationally Trained Physicians (ITPs)

- o

- Examine the structural barriers preventing ITPs from practicing in Canada.

- o

- Assess the impact of credentialing discrimination on racialized professionals [23].

-

Discuss Structural Policies That Reinforce Inequities

-

Recommend Policy Solutions for a More Equitable Healthcare System

2. Conceptual Framework: Healthcare Systemic Racism

2.1. Defining Systemic Racism in Healthcare

- Institutional racism—Policies and hiring practices within health care deny racialized professionals leadership roles and limit career progression for internationally trained physicians (ITPs) [23]. Such institutional racism contributes to the absence of diversity in decision-making, further perpetuating healthcare inequities.

- Structural Racism – Healthcare inequity is a result of social determinants, including racial segregation, financial inequality, and colonization [24]. Indigenous communities face disproportionate disease burdens due to limited access to healthcare facilities, unsafe housing, and food insecurity [29].

- Interpersonal Racism – Clinicians’ unconscious racial biases impact medical encounters in a manner that tends to cause delayed diagnosis, under-treatment, and condescending behavior towards racialized patients [3]. Empirical studies confirm that Black and Indigenous patients receive a reduced level of care and have symptoms invalidated at a higher rate [22].

Empirical Evidence of Racial Bias in Healthcare

- Maternal Health – Black and Indigenous women experience disproportionately high rates of maternal mortality and complications during childbirth. Studies highlight that racialized women frequently receive lower-quality prenatal and postnatal care, contributing to increased preterm births and infant mortality [7].

- Emergency care – Incidents such as Joyce Echaquan and Brian Sinclair’s deaths expose the danger of racial bias in medical care in an emergency room setting. Sinclair, an Indigenous male, died after 34 hours of neglect in a clinic in Winnipeg, and Echaquan, an Atikamekw female, documented racist abuse at the hands of nurses prior to her demise [6]. Black and Indigenous patients have been shown to have longer waits in an emergency room and have been consistently misdiagnosed as drug-seeking and uncooperative [22].

- Physician-Patient Interactions – Racial patients have complained for a long time about not being listened to by physicians and, as a result, receiving misdiagnoses and delayed services. Black and Indigenous peoples have long-standing, persistent, and undertreated chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mental illness [16].

2.2. Intersectionality and Health Disparities Across Races

- i.

- Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Healthcare Access

- Higher Unemployment Rates – Many racialized individuals lack employer-based health benefits, restricting their access to preventive and specialized care [24].

- Lower Levels of Incomes – Racialized groups find it difficult to afford other medical treatments, including dental, eye, and prescription medication [23].

- ii.

- Gender, Race, and Healthcare Discrimination

- Medical Neglect – Black women report high levels of neglect in reproductive care, with symptoms and pain concerns not being dealt with on numerous occasions [7].

- Forced Sterilization – Aboriginal women have been forced into forced sterilization, a practice documented in the 2010s, an expression of ongoing systemic abuse of reproductive rights [6].

- Delayed Diagnoses – Women of color’s symptoms have a high likelihood of being ignored and misdiagnosed. As a result of this, Black and Indigenous women have received delayed medical attention for medical conditions like cardiovascular disease and endometriosis [29].

- iii.

- Immigrant and Foreign-Trained Physician Barriers

- Prolonged credentialing procedures – International medical graduates must undergo expensive, time-consuming accreditation procedures that delay them from commencing practice [23].

- Discriminatory Hiring Practices – Many healthcare institutions prefer Canadian-trained professionals, leaving qualified ITPs underemployed despite severe physician shortages [24].

- Limited Residency Positions—Due to a lack of enough residency positions, most ITPs cannot obtain Canadian work experience in a position to practice medicine [16].

3. Case Studies of Systemic Racism in Canadian Healthcare

3.1. The Case of Dr. Amos Akinbiyi (Saskatchewan)

Allegations of Racial Discrimination and Retaliatory Actions

Structural Barriers for Black Physicians in Canada

- Underrepresentation in medical academia and hospital leadership, limiting career advancement [29].

- Increased workplace discrimination and burnout, with Black doctors disproportionately disciplined for minor infractions compared to white physicians [23].

- Barriers to career progression and mentorship reduce Black physicians’ access to senior roles [24].

3.2. Systemic Racism in Canadian Healthcare: Joyce Echaquan and Brian Sinclair

The Case of Brian Sinclair (Manitoba)

The Case of Joyce Echaquan (Quebec)

Key Lessons from Sinclair and Echaquan’s Cases

- Implicit Bias: Healthcare providers fail to recognize their patients’ legitimate needs, assuming intoxication, homelessness, or exaggeration of symptoms.

- Medical Neglect: In both cases, essential care was delayed or withheld, leading to preventable deaths.

- Lack of Accountability: Institutional oversight mechanisms were insufficient to effectively prevent or address these incidents.

3.3. Empirical Evidence of Anti-Black Racism in Healthcare (Montreal Study)

- i.

- Patient Experiences with Racial Bias

- Minimization of pain—Black patients consistently received less pain management due to implicit biases [5].

- Longer diagnostic delays—Black patients experienced prolonged waits for necessary tests and referrals, worsening health outcomes [23].

- Stereotyping—Black patients were less likely to receive necessary medications due to unfounded assumptions about drug misuse [7].

- ii.

- Systemic Stereotyping of Black Patients in Clinical Settings

- Racial biases shape clinical judgments, particularly in pain assessment and management [29].

- Black patients receive fewer specialist referrals, leading to more severe disease progression [24].

- Discriminatory experiences deter Black individuals from seeking medical care, undermining trust in the system [22].

3.4. Barriers for Internationally Trained Physicians (ITPs) in Canada

Case of Dr. Ismelda Ramirez (Quebec)

- i.

- Key Barriers to ITP Integration

- Limited residency spots, leaving many ITPs unable to complete licensing requirements [16].

- Expensive and time-consuming credentialing disproportionately impacts racialized immigrants [23].

- ii.

- Lengthy Wait Times: A Natural Consequence of ITP Exclusion

- 6.5 million Canadians, approximately 22% of adults, have no family doctor, a February 2024 report by the OurCare Initiative discloses [17].

- Emergency department overcrowding is worsening, with record wait times lasting more than 12–24 hours [7].

- Delays in specialist care, such as cardiology, oncology, and orthopedic care, have patients waiting months for care, exacerbating overall health outcomes [29].

- iii.

- The “Brain Drain” Phenomena and Its Consequences Worldwide

- Nearly 25% of high-income nations’ (Canada, U.S., UK, Australia) doctors are immigrants trained abroad (28).

- Physician shortages in impoverished nations worsen as professionals emigrate to more affluent countries (26).

- Most ITPs moving to Canada struggle to get licensed, are employed in low-paid, non-clinical jobs, and experience brain waste rather than skill utilization (26).

Policy Suggestions for Addressing ITP Challenges

- Increase residency posts for ITPs, prioritizing applicants who have practiced overseas before.

- Streamline credentialing procedures, reducing unnecessary and expensive licensing examinations.

- Mandate anti-bias recruitment policies, offering fair employment for foreign medical graduates.

- Implement a national qualification recognition program to assess ITPs based on qualifications and not impose Canadian-specific limitations.

- Mandatory anti-racism training for healthcare providers.

- Equitable credentialing processes for ITPs.

- Race-based health data collection to track disparities.

- Independent oversight bodies to hold institutions accountable.

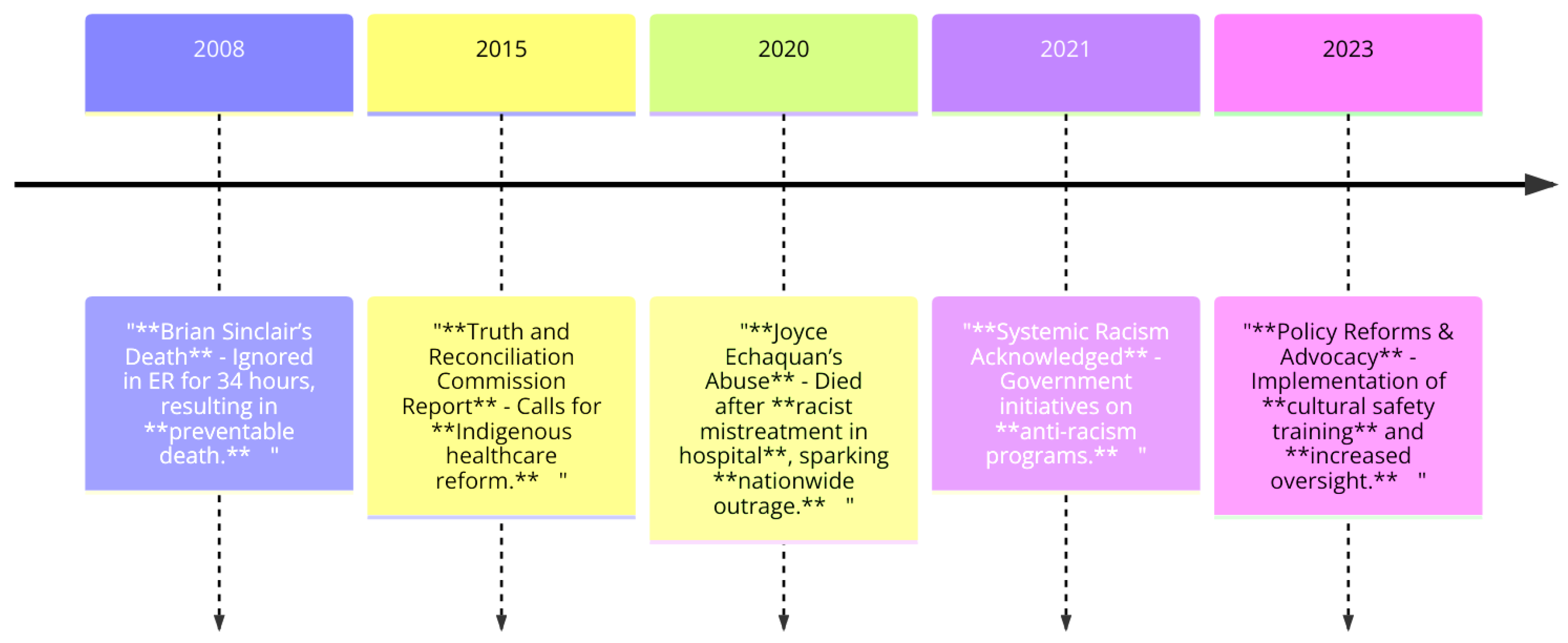

- 2008: Brian Sinclair’s death due to neglect in an emergency room after being ignored for 34 hours, marking a preventable tragedy.

- 2015: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report calls for reforms to address inequities in Indigenous healthcare.

- 2020: Joyce Echaquan’s abuse and death after racist mistreatment in a hospital sparked nationwide outrage and demands for reform.

- 2021: Systemic racism is officially acknowledged, leading to government initiatives for anti-racism programs in healthcare.

- 2023: Policy reforms and advocacy emphasize cultural safety training and increased oversight to address systemic issues.

4. Policy and Institutional Reforms

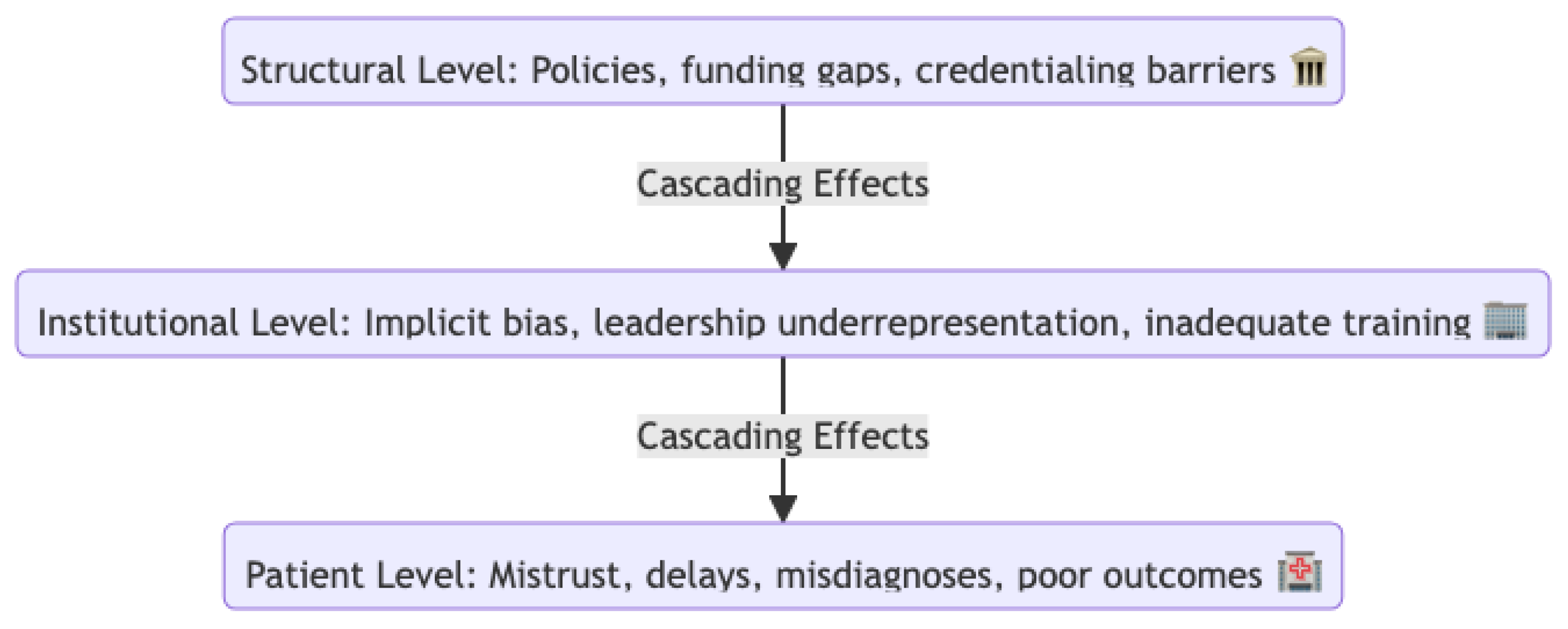

- Structural Level: At the highest level, challenges include policies, funding gaps, and credentialing barriers. These systemic issues establish the foundational inequities in healthcare infrastructure. The building icon symbolizes institutions or policy-making bodies.

- Institutional Level: Cascading from structural challenges, this level reflects the effects within organizations, such as implicit bias, underrepresentation in leadership, and inadequate training. These factors limit institutional progress toward equity. The building icon here emphasizes organizational operations.

- Patient Level: The downstream impact is experienced by patients as mistrust, delays in care, misdiagnoses, and poor health outcomes. The medical icon highlights the direct consequences of healthcare delivery.

4.1. Gaps in Canadian Healthcare Policies

Lack of Collection of Race-Based Health Data

Consequences of a Lack of Race-Based Data

- Identify and measure racial inequities in the prevalence of chronic diseases, maternal mortality, and patient outcomes [29].

- Evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for improving healthcare service equity [22].

- Develop targeted programs for health equity that address the individualized care needs of racialized communities [25].

Empirical Evidence for the Need for Race-Based Data

- Black and Indigenous maternal mortality rates are disproportionately high due to systemic racism and a lack of culturally sensitive prenatal and postnatal care [7].

- Black and Indigenous patients have historically been undertreated for pain, with explicit racial biases in clinical decision-making [29].

Insufficient Diversity in Healthcare Leadership

Structural Barriers to Leadership Diversity

- Implicit bias in hiring and promotion processes prevents racialized medical professionals from advancing into senior roles [23].

- Limited mentorship opportunities restrict career progression for Black, Indigenous, and internationally educated health professionals [7].

- Exclusion from research funding and decision-making boards perpetuates systemic inequities and hinders the development of inclusive policies [5].

Credentialing Barriers for Internationally Trained Physicians (ITPs)

Licensing Bottlenecks Violating ITPs’ Right to Practice

- Limited residency slots disproportionately favor Canadian-trained medical graduates, reducing ITPs’ chances of securing clinical placements [5].

- Practice Ready Assessment (PRA) programs—an alternative pathway for ITPs—are underfunded, inconsistently implemented across provinces, and largely inaccessible [24].

- Expensive and unnecessary licensing examinations place an undue burden on racialized immigrant doctors [23].

Discriminatory Hiring Practices

4.2. Recommendations for Systemic Reforms

- Implicit bias training for medical professionals, including physicians and nursing staff.

- Culturally safe care protocols for Black, racialized, and Indigenous communities.

- Workplace diversity training for medical schools in a bid to prevent discriminatory recruitment and career development processes.

- Enhanced racial and cultural competency in patient relations.

- Reduction in racial gaps in care, diagnoses, and pain management [22].

- Greater diversity in leadership and increased racialized clinicians in senior positions.

- Standardized racial and ethnic collection of health information in hospitals, clinics, and public health departments.

- Public reporting mandates hospitals to report racial discrepancies in care and outcomes.

- Incorporation of racial factors in national performance assessments for health.

- Enhanced data-driven policy interventions to address healthcare inequities.

- Greater transparency and accountability in medical institutions.

- Decrease in racial gaps in long-term disease prevalence, pregnancy-related maternal deaths, and access to specialist medical care [29].

- Racial disparities in health outcomes are summarized in Table 1, showing key inequities among different demographic groups.

| Demographic Group | Disparity Example | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Indigenous Patients | High rates of chronic illnesses such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases | Need for targeted chronic disease prevention programs |

| Black Canadians | Higher maternal mortality rates compared to non-racialized groups | There is an urgent need for improved maternal healthcare and anti-racism training |

| Other Racialized Groups | Increased instances of misdiagnoses and delayed treatments | Requirement for equity in diagnostic procedures and timely care |

- Expansion of Practice Ready Assessment (PRA) programs in all provinces.

- Increase in ITP-specific residency positions, reducing overreliance on Canadian-trained candidates.

- Reform licensure exams to authenticate global medical competency and eliminate excessive testing requirements [23].

- Mandatory anti-bias hiring policies in hospitals and clinics.

- Increased ITP workforce integration, overcoming physician shortages.

- Greater diversity in medical professionals, improving culturally sensitive care.

- Reducing unnecessary barriers to employment enables qualified professionals to contribute to healthcare.

- Oversee racial inequity in healthcare institutions.

- Investigate systemic racism in medical settings.

- Hold hospitals and policymakers accountable for equity-based reforms.

- Lack of audits: Without proper oversight, racial health inequities remain unchecked [27].

- Lack of accountability mechanisms: The absence of independent review bodies allows institutions to perpetuate discrimination with impunity [22].

- Underrepresentation in leadership: The lack of racialized professionals in executive roles results in policies that fail to reflect lived realities [7].

- Conducting routine audits on racial disparities in patient care, workforce composition, and clinical outcomes [24].

- Assessing whether racialized groups receive fair treatment compared to non-racialized patients [29].

- Collecting race-based health data to monitor trends in discrimination, pain management, and access to care [25].

- Establishing real-time reporting mechanisms for racial discrimination claims by medical professionals and patients [23].

- Conducting independent case reviews of medical neglect, racial profiling, and workforce discrimination [22].

- Making anti-racism training mandatory for all healthcare workers [29].

- Ensuring medical schools implement diverse recruitment and leadership promotion policies [5].

- Implementing performance metrics for culturally competent care programs [27].

- Proposing policy reforms to address systemic inequities in healthcare services [24].

- Holding hospitals accountable for preventable racial disparities in treatment and health outcomes [7].

- Discriminatory hiring: Black medical professionals continue to face barriers to employment, as seen in Dr. Amos Akinbiyi’s lawsuit against the Saskatchewan Health Authority, highlighting racial discrimination in healthcare employment [30].

- Regularly reporting racial inequities in patient care and healthcare workforce diversity [24].

- Explicit channels for professionals and patients to report racial discrimination in medical institutions [23].

- Increased monitoring of patient-provider interactions to prevent racial stereotyping, improper pain management, and diagnostic neglect [29].

- Stronger diversity mandates for medical school admissions, hiring, and promotions [5].

- Performance measures to ensure hospitals adopt equitable, culturally appropriate patient care standards [27].

- Demonstrates a clear commitment to eradicating racial inequities through independent investigations and policy enforcement [29].

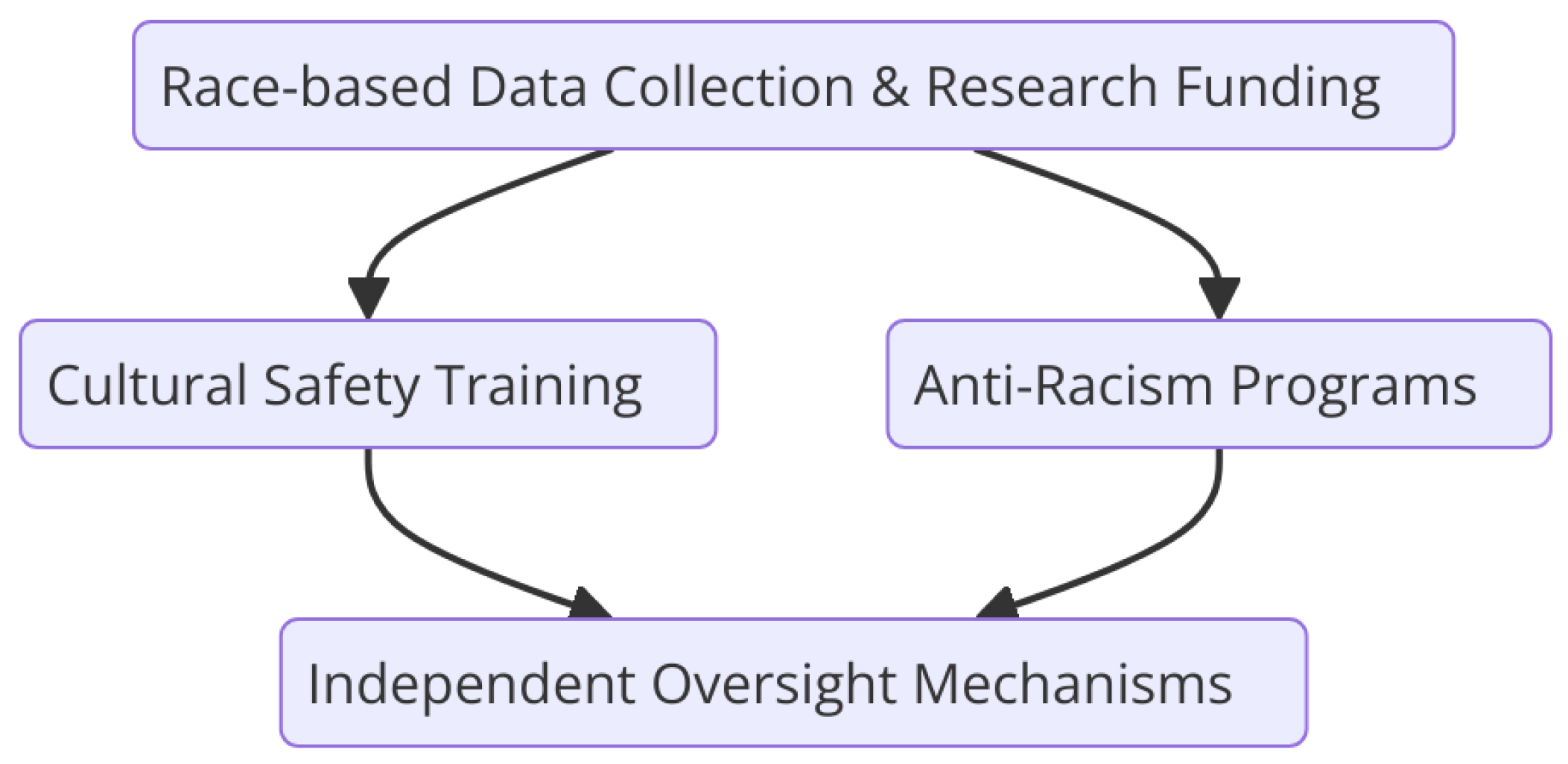

- Cultural Safety Training: Educating healthcare professionals to provide care that respects the cultural identities of patients.

- Anti-Racism Programs: Initiatives aimed at reducing biases and systemic discrimination within healthcare institutions.

5. Conclusion and Call to Action

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical Statement

Consent Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Allan B, Smylie J. First Peoples, second class treatment: The role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Wellesley Institute. 2015. Available from: https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Full-Report-FPSCT-Updated.pdf.

- Béland D, Zarzeczny A. Medical tourism and national health care systems: An institutionalist research agenda. Global Health. 2018;14(1):68. [CrossRef]

- Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough DL. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among Black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):43–52. [CrossRef]

- Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. The intergenerational effects of Indian residential schools: Implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51(3):320–38. [CrossRef]

- Boyer Y. Healing racism in Canadian health care. CMAJ. 2017;189(46):E1408–9. [CrossRef]

- British Columbia Ministry of Health. In plain sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific racism and discrimination in B.C. healthcare. 2020. Available from: https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Summary-Report.pdf.

- Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie J, et al. Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: Evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:544. [CrossRef]

- Chughtai W, Lee V. Canada has a doctor shortage, but thousands of foreign-trained physicians already here still face barriers. CBC News. 2025 Jan 17. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/international-doctors-canada-barriers-1.7428598.

- Canadian Human Rights Commission. Discussion paper on systemic racism. 2023. Available from: https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/discussion_paper_on_systemic_racism.pdf.

- College of Family Physicians of Canada. Health and health care implications of systemic racism on Indigenous peoples in Canada. 2016. Available from: https://www.cfpc.ca/en/policy-innovation/health-policy-goverment-relations/cfpc-policy-papers-position-statements/racisim-indigenous-peoples.

- DeSouza R. Wellness for all: The possibilities of cultural safety and cultural competence in New Zealand. J Res Nurs. 2008;13(2):125–35. [CrossRef]

- Devine PG, Forscher PS, Austin AJ, Cox WT. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48(6):1267–78. [CrossRef]

- Geary A. Ignored to death: Brian Sinclair’s death caused by racism, inquest inadequate, group says. CBC News. 2017 Sep 18. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/winnipeg-brian-sinclair-report-1.4295996.

- Government of Canada. Check your Express Entry score. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/immigrate-canada/express-entry/check-score.html.

- Government of Canada. Minister of National Defense Advisory Panel on Systemic Racism and Discrimination: Final report. 2022. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/dnd-mdn/documents/reports/2022/mnd-ap-final-report-7-jan-2022.pdf.

- Government of Canada. Government of Canada actions to address anti-Indigenous racism in health systems. 2023. Available from: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1611863352025/1611863375715.

- Government of Canada. Supporting Canada’s health workers by improving health workforce research, planning, and data. 2024. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2024/07/supporting-canadas-health-workers-by-improving-health-workforce-research-planning-and-data1.html.

- Kerr S, Penney L, Moewaka Barnes H, McCreanor T. Kaupapa Maori Action Research to improve heart disease services in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Ethn Health. 2009;15(1):15–31. [CrossRef]

- Loppie S, Reading C, de Leeuw S. Indigenous experiences with racism and its impacts. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. 2014. Available from: https://www.nccih.ca/634/Indigenous_Experiences_with_Racism_and_its_Impacts.nccih?id=1016.

- Loppie Reading C, Wien F. Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. 2009. Available from: https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/determinants/RPT-HealthInequalities-Reading-Wien-EN.pdf.

- Mullan F. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1810–8. [CrossRef]

- OmiSoore D. Systemic Anti-Blackness in Healthcare: What the COVID-19 Pandemic Revealed about Anti-Black Racism in Canada. HealthcarePapers. 2023;21(3):9–23. Available from: https://www.longwoods.com/content/27196/healthcarepapers/systemic-anti-blackness-in-healthcare-what-the-covid-19-pandemic-revealed-about-anti-black-racism-i.

- Phillips-Beck W, Eni R, Lavoie JG, et al. Confronting racism within the Canadian healthcare system: Systemic exclusion of First Nations from quality and consistent care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8343. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Inequalities in health of racialized adults in Canada. 2023. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/science-research-data/inequalities-health-racialized-adults-18-plus-canada.html.

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academies Press; 2003. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/read/12875/chapter/1.

- Tankwanchi AB, Ozden C, Vermund SH. Physician emigration from sub-Saharan Africa to the United States: analysis of the 2011 AMA physician masterfile. PLoS Med. 2013;10(9):e1001513. [CrossRef]

- Walker R, St. Pierre-Hansen N, Cromarty H, et al. Measuring cross-cultural patient safety: Identifying barriers and developing performance indicators. Healthc Q. 2010;13(1):64–71. [CrossRef]

- Wellesley Institute. Racialized people’s perceptions of and responses to differential health care. Regent Park Community Health Centre; 2007. Available from: https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Racialized-Perceptions-and-Responses.pdf.

- Williams KKA, Baidoobonso S, Lofters A, et al. Anti-Black racism in Canadian health care: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(3152). [CrossRef]

- Quon A. Doctor’s lawsuit against Sask. Health Authority alleges discrimination at Regina General Hospital. CBC News. 2025 Jan 31. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/sha-lawsuit-doctor-discrimination-1.7443882.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).