Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Survey Measures

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

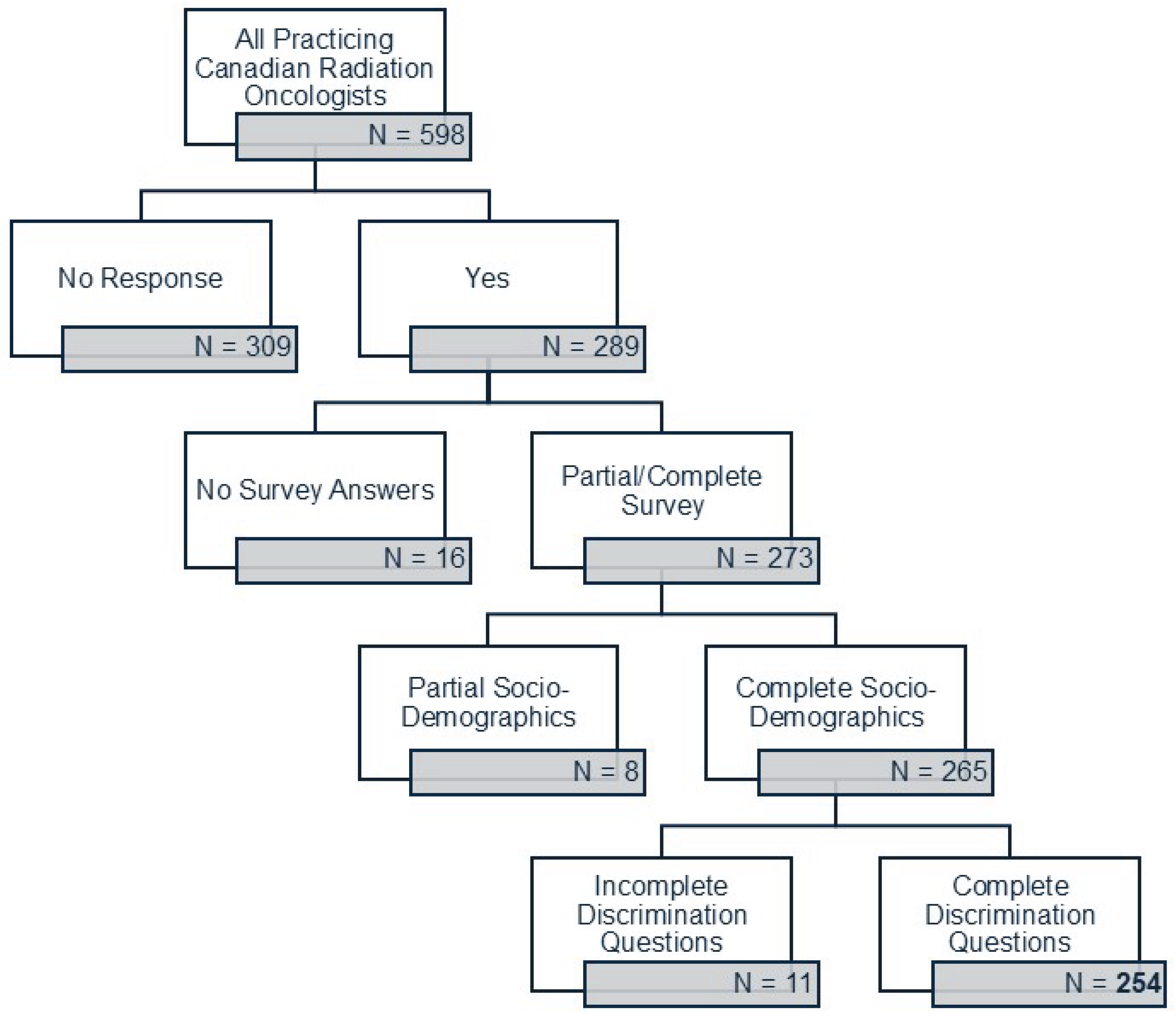

3.1. Survey Response

3.2. Demographics

3.3. Career Satisfaction and Mentorship

3.4. Workplace Culture and Experiences of Discrimination or Harassment

4. Discussion

| Question | Select Summarized and Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| What should oncology departments do to address mistreatment or harassment? | (i) training/education: “Better training with easily accessible resources. Publicize them to make them known to everyone. “Open discussions at the department meetings. Educational workshops. Form special committees.” (ii) having clear institutional policies on how to report mistreatment (anonymously or via a structured complaint pathway): “Have open in-person conversations led by leadership to clarify expectations, policies and procedures, and have a forum to confidentially report mistreatment/harassment to for victims and an avenue for understanding options for formal reporting.” “A standardized / easy to access / anonymous reporting method is needed. There should be an independent process/body to administrate this to reduce bias.” (iii) having meaningful and measured corrective measures or repercussions to mistreatment: “Incidents should be fully investigated and sorted out and a clear message of no tolerance for any form of mistreatment or harassment should be in place.” “We need more than investigation of just the incident. There needs to be an assessment of the work environment to determine if this is an isolated behaviour or whether more widespread issues exist. Mistreatment and harassment should not be tolerated in any form.” (iv) creating safe environments where reporting mistreatment or harassment is encouraged: “Explore the cultural factors that are leading to the issues and be willing to significantly disrupt culture that is perpetuating these factors. There needs to be a way to report incidents in a confidential and safe manner.” “Need more diversity in leadership. Most leaders are one gender and appear the same, we need to hire people from multiple backgrounds that represent all ROs to be leaders/administration.” |

| What should oncology departments do to advance equity diversity and inclusion (EDI) in the workplace? | (i) advancement supports for underrepresented persons in RO to achieve leadership positions: “Support leadership training for underrepresented faculty and trainee members.” “Stop looking for a certain archetype as this creates a selection bias. We need to clear policies for promotion to hire people in leadership positions with different skills and backgrounds.” (ii) mandatory and comprehensive EDI education and training: “There needs to be in-person mandatory presentations to learn what EDI is and how it may manifest, clear training on policies and institutional goals related to EDI, with discussion around how to mitigate barriers to EDI goals.” “We need to educate ourselves on best practices and make conscious efforts to advance and seek expertise to improve EDI training.” |

|

What should oncology departments do to make faculty hiring practices more equitable? |

(i) transparent, inclusive, and equitable hiring practices: “We need better diversity in hiring practices, and teaching on why this is valuable. Departments need to make this a priority and openly discuss how they are taking the lead on improving recruitment processes and mitigating unconscious biases.” “There needs to be formal processes and hiring practices, informed by EDI experts, that supports the development of a diverse work force and decrease barriers for those who are underrepresented with inclusive language.” (ii) ensuring that hiring committees are diverse themselves: “Committees should be composed of a diverse group of individuals to make hiring decisions. Members should have mandatory training on hiring policies and best practices.” “Follow established university hiring practices that already focus on EDI and fairness and seek advice from hospital/university affiliates to ensure that the committee and department hiring is open to equity and diversity and hiring members are from diverse backgrounds.” (iii) hiring candidates externally/from a different training background: “There should be an external review of any hire that confirms that a job posting was publicly available with specific considerations as to whether potential hires external to the department were given due consideration. The hiring of our own trainees can perpetuate the retention of a stagnant culture, which is reinforced when we are disrupted by an external hire (i.e., the culture conflict often makes everyone wish the hire was internal, when in fact the disruption of group think was a positive). |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K. M. Winkfield and D. Gabeau, “Why Workforce Diversity in Oncology Matters,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys., vol. 85, no. 4, pp. 900–901, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Germino et al., “Tailored Mentorship for the Underrepresented and Allies in Radiation Oncology: The Association of Residents in Radiation Oncology Equity and Inclusion Subcommittee Mentorship Experience,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., vol. 116, no. 2, pp. 368–374, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Filut, M. Alvarez, and M. Carnes, “Discrimination Toward Physicians of Color: A Systematic Review,” J. Natl. Med. Assoc., vol. 112, no. 2, pp. 117–140, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Ruzycki, P. Roach, J. Holroyd-Leduc, C. Barnabe, and S. B. Ahmed, “Experiences and Perceptions of Racism and Sexism Among Alberta Physicians: Quantitative Results and Framework Analysis of a Cross-Sectional Survey,” J. Gen. Intern. Med., vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 165–175, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. N. Dyrbye et al., “Physicians’ Experiences With Mistreatment and Discrimination by Patients, Families, and Visitors and Association With Burnout,” JAMA Netw. Open, vol. 5, no. 5, p. e2213080, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gasnier et al., “Establishing a benchmark of diversity, equity, inclusion and workforce engagement in radiation oncology in Europe – An ESTRO collaborative project,” Radiother. Oncol., vol. 171, pp. 198–204, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Aldosary et al., “A First Look at Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion of Canadian Medical Physicists: Results From the 2021 COMP EDI Climate Survey,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys., vol. 116, no. 2, pp. 305–313, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Lightfoote et al., “Improving Diversity, Inclusion, and Representation in Radiology and Radiation Oncology Part 1: Why These Matter,” J. Am. Coll. Radiol. JACR, vol. 11, no. 7, p. 673, 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Gomez and P. Bernet, “Diversity improves performance and outcomes,” J. Natl. Med. Assoc., vol. 111, no. 4, pp. 383–392, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Swartz, A.-G. S. Palermo, S. K. Masur, and J. A. Aberg, “The Science and Value of Diversity: Closing the Gaps in Our Understanding of Inclusion and Diversity,” J. Infect. Dis., vol. 220, no. Suppl 2, pp. S33–S41, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Takeshita et al., “Association of Racial/Ethnic and Gender Concordance Between Patients and Physicians With Patient Experience Ratings,” JAMA Netw. Open, vol. 3, no. 11, p. e2024583, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Haque et al., “Cancer mortality rates by racial and ethnic groups in the United States, 2018-2020,” JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst., vol. 115, no. 7, pp. 822–830, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Gilligan, P. S. Wang, R. Levin, P. W. Kantoff, and J. Avorn, “Racial differences in screening for prostate cancer in the elderly,” Arch. Intern. Med., vol. 164, no. 17, pp. 1858–1864, Sep. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Dehal, A. Abbas, and S. Johna, “Racial disparities in clinical presentation, surgical treatment and in-hospital outcomes of women with breast cancer: analysis of nationwide inpatient sample database,” Breast Cancer Res. Treat., vol. 139, no. 2, pp. 561–569, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Ginsburg et al., “A population-based study of ethnicity and breast cancer stage at diagnosis in Ontario,” Curr. Oncol., vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 97–104, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- of Medicine, Unequal Treatment Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington: National Academies Press, 2002.

- F. C. Stanford, “The Importance of Diversity and Inclusion in the Healthcare Workforce,” J. Natl. Med. Assoc., vol. 112, no. 3, pp. 247–249, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Winkfield, C. R. Flowers, and E. P. Mitchell, “Making the Case for Improving Oncology Workforce Diversity,” Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book, no. 37, pp. 18–22, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Wang, E. H. Dibble, I. C. Gibbs, E. Rubin, and J. R. Parikh, “The 2021 ACR/Radiology Business Management Association Workforce Survey: Diversity in Radiology,” J. Am. Coll. Radiol. JACR, vol. 20, no. 12, pp. 1269–1276, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “Does the AAMC’s Definition of ‘Underrepresented in Medicine’ Promote Justice and Inclusivity?,” AMA J. Ethics, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. E960-964, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Allen et al., “Understanding Equity, Diversity and Inclusion within Canadian Radiation Oncology: Experiences of Residents and Fellows,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., vol. 120, no. 2, Supplement, pp. e2–e3, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Government of Canada, “Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population.” Accessed: Aug. 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E.

- “Scott’s Medical Database metadata | CIHI.” Accessed: Aug. 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/scotts-medical-database-metadata.

- “Supply, Distribution and Migration of Physicians in Canada, 2022 — Methodology Notes”.

- K. Kwok, N. Samson, C. M. Doll, L. Barbera, and S. K. Loewen, “Representation of Women in Canadian Radiation Oncology Trainees and Radiation Oncologists: Progress or Regress?,” Adv. Radiat. Oncol., vol. 7, no. 6, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Loewen et al., “National Trends and Dynamic Responses in the Canadian Radiation Oncology Workforce From 1990 to 2018,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys., vol. 105, no. 1, pp. 31–41, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pickel and N. Sivachandran, “Gender trends in Canadian medicine and surgery: the past 30 years,” BMC Med. Educ., vol. 24, no. 1, p. 100, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Chapman, W.-T. Hwang, and C. Deville, “Diversity based on race, ethnicity, and sex, of the US radiation oncology physician workforce,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys., vol. 85, no. 4, pp. 912–918, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Suzuki et al., “Gender Equity and Workplace Mistreatment in Oncology: Results From a Survey by the Brazilian Society of Clinical Oncology,” JCO Glob. Oncol., no. 11, p. e2400323, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- “Black medical students accepted to class of 2024 are largest contingent in Canadian history,” The Varsity. Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://thevarsity.ca/2020/06/24/black-medical-students-accepted-to-class-of-2024-are-largest-contingent-in-canadian-history/.

- S. C. Government of Canada, “More than half of Canada’s Black population calls Ontario home.” Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/441-more-half-canadas-black-population-calls-ontario-home.

- K. R. G. Hendrickson et al., “2021 AAPM Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Climate Survey Executive Summary,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys., vol. 116, no. 2, pp. 295–304, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M.-A. Valfort, “Do anti-discrimination policies work?,” IZA World Labor, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Tankard and E. L. Paluck, “The Effect of a Supreme Court Decision Regarding Gay Marriage on Social Norms and Personal Attitudes,” Psychol. Sci., vol. 28, no. 9, pp. 1334–1344, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Broockman and J. Kalla, “Durably reducing transphobia: A field experiment on door-to-door canvassing,” Science, vol. 352, no. 6282, pp. 220–224, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Narayan, “The limits of using grievance procedures to combat workplace discrimination,” Ind. Relat. J. Econ. Soc., vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 26–42, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. C. Paradis et al., “Gender-Based Discrimination and Sexual Harassment in Medical Physics,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys., vol. 116, no. 2, pp. 314–327, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Chary, M. O. Fofana, and H. S. Kohli, “Racial Discrimination from Patients: Institutional Strategies to Establish Respectful Emergency Department Environments,” West. J. Emerg. Med., vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 898–902, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

| Demographic category (number of respondents) | Demographic characteristic | Survey – RO data | 2022 CIHI data - RO population1 | 2021 Census data2 | Significance/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender Identity (267) |

Man Woman |

168 (63%) 99 (37%) |

380 (64%) 218 (36%) |

12.9m (48%) 13.8m (52%) |

|

|

Age (273) |

25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+ |

15 (5%) 107 (39%) 82 (30%) 47 (17%) 22 (8%) |

- |

4.4m (22%) 4.4m (22%) 4.0m (20%) 3.3m (16%) .95m (4%) |

Census data only included for working persons, not the general population |

|

Sexual Orientation (Multiselect, 261) |

Heterosexual Gay Bisexual Asexual Queer Pansexual Questioning |

246 (94%) 10 (4%) 4 (2%) 1 (<1%) 0 0 0 |

- | - | |

|

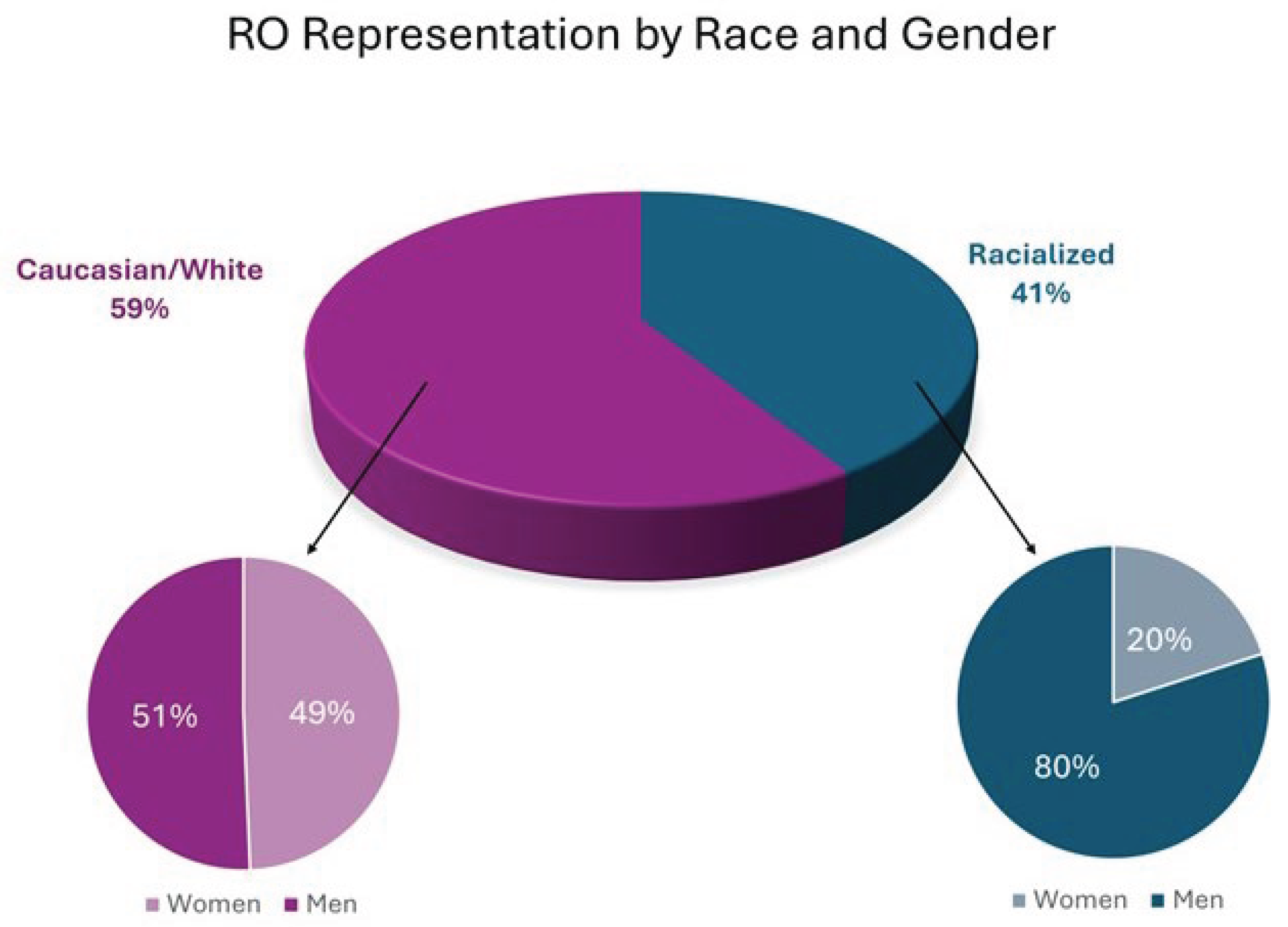

Race/Ethnicity (Multiselect, 255) |

Caucasian/White Racialized Group Chinese South Asian4 Black Southeast Asian5 First Nations Pooled Others |

150 (59%) 105 (41%) 39 (15%) 31 (12%) 5 (2%) 4 (1%) 1 (<1%) 25 (10%) |

- |

25m (70%) 9.6m (27%) 1.7m (5%) 2.5m (7%) 1.5m (4%) 1.3m (4%) 1.8m (5%) 2.5m (7%) |

|

| Race and Gender – Subset Analysis | Caucasian Overall Caucasian Male RO Caucasian Female RO |

150 (59%) 76 (51%) 74 (49%) |

- |

25m (70%) 9.6m (27%) |

Chi-squared for Caucasian women vs racialized women = 22.7, p<0.001 |

| Racialized Overall Racialized Male RO Racialized Female RO |

105 (41%) 84 (80%) 21 (20%) |

||||

|

Religion (Multiselect, 264) |

Christianity Atheist/No religion Hinduism Islam Spiritual Judaism Buddhism Sikhism Other |

107 (41%) 106 (40%) 12 (5%) 11 (4%) 11 (4%) 11 (4%) 3 (1%) 1 (<1%) 2 (<1%) |

- |

19.3m (53%) 12.6m (34%) .83m (2%) 1.7m (5%) 80k (<1%) .36m (1%) .34m (1%) .77m (2%) 229k (<1%) |

|

|

Are you identifiable as a member of a religion? (262) |

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no Not sure |

17 (6%) 23 (9%) 75 (29%) 133 (51%) 14 (5%) |

- |

- |

|

|

What religion would people assume you belong to? (Multiselect, 252) |

Christianity Hinduism Buddhism Islam Judaism Confucianism Sikhism Atheist/Agnostic |

159 (63%) 20 (8%) 19 (8%) 19 (8%) 18 (7%) 8 (3%) 5 (2%) 3 (1%) |

- |

- |

|

|

Geography (265) |

Ontario Manitoba and West Quebec Maritimes |

95 (36%) 85 (32%) 68 (26%) 17 (6%) |

233 (39%) 179 (30%) 143 (24%) 43 (7%) |

10.3m (38%) 8.4m (31%) 6.2m (23%) 2.0m (8%) |

|

|

Citizenship Status (265) |

Canadian *By birth *By immigration PR Work Visa |

255 (96%) 178 (67%) 77 (29%) 6 (2%) 4 (1%) |

- |

33.1m (91%) 27m (74%) 6.1m (17%) - - |

|

|

Marital Status (267) |

Married/Domestic Single Widowed Divorced/Separated |

228 (85%) 26 (10%) 4 (1%) 9 (3%) |

- |

4.9m (57%) 3.7m (43%) - - |

|

|

How many dependents do you have? (273) |

0 1 2 3+ |

78 (29%) 42 (15%) 79 (29%) 74 (27%) |

- | - | |

|

Primary language (264) |

English French Another language |

157 (59%) 54 (20%) 53 (20%) |

- | 27.8m (76%) 8m (22%) .67m (2%) |

|

|

Degrees earned (Multiselect, 273) |

MD Masters PhD MBA JD |

273 (100%) 89 (33%) 32 (12%) 10 (4%) 2 (1%) |

- | - | |

|

Where MD was obtained (273) |

Canada International |

220 (81%) 53 (19%) |

454 (76%) 144 (24%) |

- |

|

|

Residency Training Location (273) |

Canada Elsewhere |

239 (88%) 34 (12%) |

- |

- |

|

|

Years of Practice (273) |

<5 6-10 11-15 16-20 21-25 26+ |

41 (15%) 58 (21%) 66 (24%) 24 (9%) 37 (14%) 47 (17%) |

- | - | |

|

Academic Rank (273) |

Assistant Professor Associate Full Professor Lecturer No Appointment |

110 (40%) 81 (30%) 41 (15%) 25 (9%) 16 (6%) |

- | - | |

|

How large is your practice group? (273) |

1-5 6-10 11-20 21-30 30+ |

16 (6%) 41 (15%) 113 (41%) 68 (25%) 35 (13%) |

- | - | |

|

Do parents have a degree(s)? (273) |

One Both Neither No answer |

57 (21%) 117 (43%) 94 (34%) 5 (2%) |

- | - | |

|

Income when growing up (235) |

$150,000 + $100,000-$150,000 $50,000-$100,000 $25,000-$50,000 < $25,000 I don’t know No answer |

54 (23%) 38 (16%) 76 (32%) 28 (12%) 21 (9%) 3 (1%) 15 (6%) |

- | - | |

|

How many peer-reviewed publications have you been an author on? (260) |

<5 5-10 10-25 25-50 50-100 >100 |

59 (23%) 49 (19%) 52 (20%) 40 (15%) 26 (10%) 34 (13%) |

- | - | |

|

Do you view yourself as having a disability? (270) |

Yes No Prefer not to answer |

10 (4%) 256 (95%) 4 (1%) |

- | 27%3 73% N/A |

|

|

What is your disability? (multi-select, 16) |

Deaf/hearing Mobility/physical Mental health Autism Cognitive Chronic illness Speech Other |

3 (19%) 3 (19%) 3 (19%) 2 (13%) 1 (6%) 1 (6%) 1 (6%) 2 (13%) |

- | - |

| Question (Number of Respondents) | Study Sample | Significance/Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

"All in all, I feel satisfied with my job” (248) |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree nor disagree Agree Strongly agree |

14 (6%) 16 (6%) 31 (13%) 114 (46%) 73 (29%) |

|

|

"All in all, I feel satisfied with my job” – Subset Analysis by gender of those picking “Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” (30, percentage is of overall gender) |

Male Female |

22 (13%) 8 (8%) |

Chi-squared comparing gender vs satisfaction = 1.745, p=0.18 |

|

"All in all, I feel satisfied with my job” – Subset Analysis by race of those picking “Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” (30, percentage is of overall race) |

Caucasian/White Racialized |

12 (8%) 18 (17%) |

Chi-squared comparing race vs satisfaction = 4.563, p<0.03 |

|

How often have you thought about moving to a different institution? (262) |

Never Once or twice Sometimes Often Very often |

51 (19%) 83 (32%) 87 (33%) 23 (9%) 18 (7%) |

|

|

How often have you felt regret about deciding to become a physician? (262) |

Never Once or twice Sometimes Often Very often |

131 (50%) 50 (19%) 57 (22%) 16 (6%) 8 (3%) |

|

|

A formal mentorship program exists within my department (260) |

Yes No |

107 (41%) 153 (59%) |

|

|

I currently act as a mentor to a trainee(s) and/or colleague(s) (260) |

Yes, trainee(s) Yes, colleague(s) Yes, trainee(s) and colleague(s) No |

62 (24%) 22 (8%) 35 (13%) 143 (55%) |

|

|

I currently have at least one mentor (258) |

Yes No |

64 (25%) 194 (75%) |

|

|

I currently have at least one mentor – Subset Analysis by gender for “No” responses (194, percentage is of overall gender) |

Male Female |

123 (73%) 71 (72%) |

|

|

I currently have at least one mentor – Subset Analysis by race for “No” responses (194, percentage is of overall race) |

Caucasian/White Racialized |

115 (77%) 79 (75%) |

|

|

It is important I have a mentor with similar demographic characteristics to me (260) |

Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree nor disagree Agree Strongly agree |

33 (13%) 65 (25%) 116 (45%) 40 (15%) 6 (2%) |

|

| Question (Number of Respondents) | Study Sample | Significance/Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Thinking about the past year, how would you rate the culture of respect in your department? (263) |

Excellent Very good Good Adequate Poor Very Poor |

59 (22%) 87 (33%) 54 (21%) 33 (13%) 20 (8%) 10 (4%) |

|

|

How often did you feel that you experienced discrimination in the past 5 years while working as a radiation oncologist? (252) |

Never Once 2 - 4 times 5 - 10 times Regularly/ongoing basis |

146 (58%) 8 (3%) 54 (21%) 25 (10%) 19 (8%) |

|

|

In the past 5 years as an RO on what basis have you felt discriminated upon? (Multiselect, 201) |

Gender Race/ethnicity Age Pregnancy / caregiving National origin Marital status Level of education Political view Disability Religion Language Sexual orientation Socioeconomic status Lack of research interest Seniority IMG status Caring for elderly parents Travelling during Covid Lack of children Medical specialty |

52 (26%) 41 (20%) 31 (15%) 19 (9%) 13 (6%) 8 (4%) 7 (3%) 6 (3%) 4 (2%) 4 (2%) 5 (2%) 3 (1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) |

|

|

What was the role of the person(s) who discriminated against you? (Multiselect, 183) |

Faculty member Patient / Patient’s family Staff (administrative, non-faculty) Other allied health professional Nurse Resident / Clinical Fellow Funding agencies |

58 (32%) 58 (32%) 25 (14%) 19 (10%) 16 (9%) 6 (3%) 1 (<1%) |

|

|

Was the person who discriminated against you someone in a position to directly affect your academic, and/or professional opportunities? (251) |

Yes No Not sure Does not apply No answer |

48 (19%) 52 (21%) 7 (3%) 138 (55%) 6 (2%) |

|

|

If you experienced harassment/discrimination perpetrated by a patient/family at any time during your career, on what basis did they discriminate against you? (Multiselect, 120) |

Race/ethnicity Gender Age National origin Other Sexual orientation Disability Religion |

43 (36%) 29 (24%) 27 (23%) 10 (8%) 8 (7%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) |

Chi-squared comparing sources of discrimination by gender = 39.2, p<0.0001 |

|

Women and Reported Discrimination Reasons - Subset Analysis (Multiselect, 52) |

Gender Age Pregnancy/Caregiver Responsibilities Race/ethnicity Marital Status Other |

44 (85%) 24 (46%) 14 (27%) 12 (23%) 7 (13%) 5 (10%) |

|

|

Men and Reported Discrimination Reasons - Subset Analysis (Multiselect, 47) |

Race/ethnicity Age Gender Childcare/Caregiver Responsibilities Marital Status Other |

30 (64%) 9 (19%) 7 (15%) 4 (8.5%) 1 (2%) 14 (30%) |

|

| Ethnicity and Reporting at Least One Type of Discrimination - Subset Analysis | White Racialized |

44/149 (30%) 67/111 (60%) |

Chi-squared = 24.713, p<0.001 |

|

"I understand how to and feel comfortable reporting harassment incidents at my workplace“ (252) |

Strongly disagree Somewhat disagree Neither agree/disagree Somewhat agree Strongly agree |

39 (15%) 75 (30%) 44 (17%) 66 (26%) 28 (11%) |

|

|

I have training regarding sexual harassment (multiselect, 276) |

No training In person Online module Review of institutional policy |

68 (25%) 10 (4%) 149 (54%) 49 (18%) |

|

|

I have training regarding racism (multiselect, 266) |

No training In person Online module Review of institutional policy |

82 (31%) 9 (3%) 127 (48%) 48 (18%) |

|

|

I have training regarding LGBTQ2+ peoples (multiselect, 271) |

No training In person Online Review of institutional policy |

119 (44%) 10 (4%) 95 (35%) 47 (17%) |

|

|

I have training regarding Aboriginal/Indigenous health (multiselect, 286) |

No training In person Online module Review of institutional policy |

50 (17%) 26 (9%) 164 (57%) 46 (16%) |

|

|

I have training regarding learner mistreatment (multiselect, 278) |

No training In person Online module Review of institutional policy |

99 (36%) 23 (8%) 105 (38%) 51 (18%) |

|

|

I have training regarding equity, diversity and inclusion (multiselect, 282) |

No training In person Online module Review of institutional policy |

69 (24%) 18 (6%) 145 (51%) 50 (18%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).