1. Introduction

Violence, as defined by the World Health Organization in the World Report on Violence and Health [WRVH], encompasses “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either result in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation” [

1] [

2]. In this context, violence extends beyond physical injury to encompass instances where psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation occurs; thus, acts of omission or neglect, not solely commission, can be categorized as violent [

1].

While the terms “violence” and “abuse” are frequently used interchangeably, a distinction exists between the two. Violence may denote singular acts, whereas abuse typically denotes a prolonged pattern of behavior wherein one person seeks to exert control over another [

3].

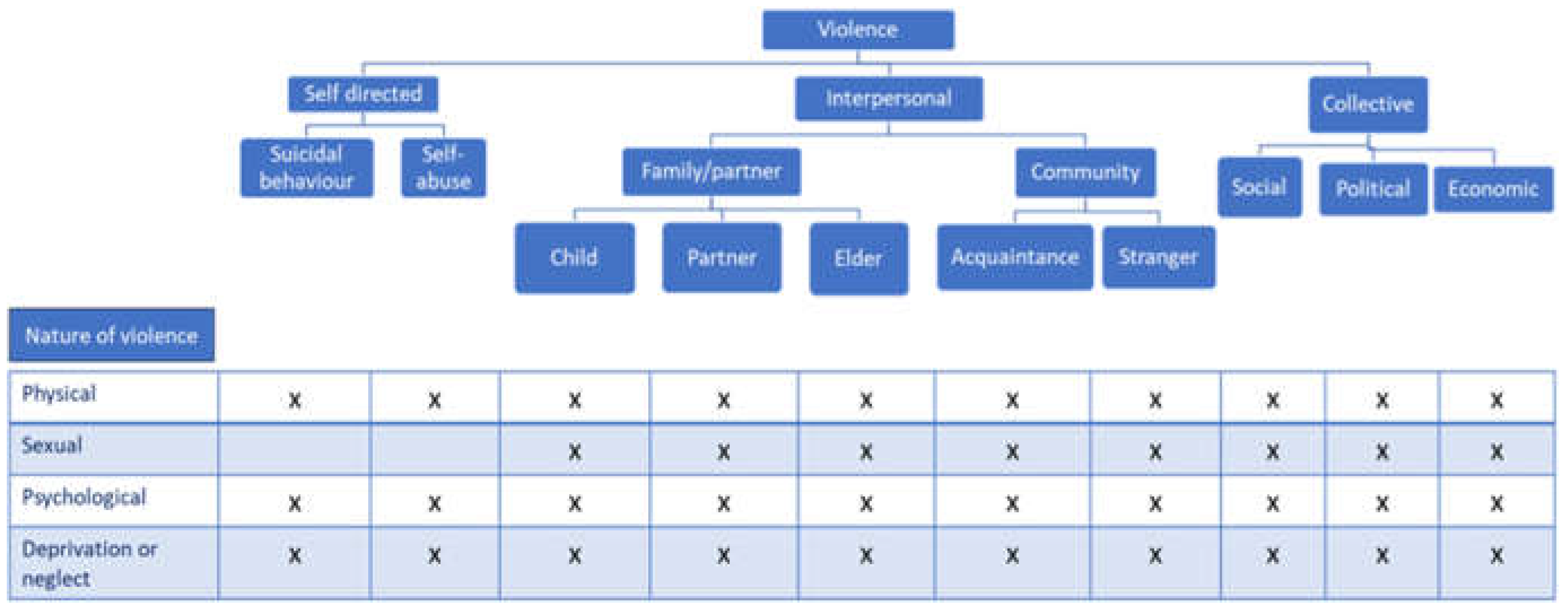

The WRVH classifies violence into three categories based on the perpetrator: self-directed, interpersonal, or collective. Furthermore, it delineates four additional categories based on the nature of violence: physical, sexual, psychological, or involving deprivation or neglect. Given the multifaceted nature of violence, various forms may co-occur, rendering them non-mutually exclusive. [

1]

Figure 1

The International Classification of Diseases [ICD] codes, used around the world to code mortality and morbidity data, include mechanism of injury codes for assault, sexual assault, neglect, abandonment, and maltreatment[

4]. These are grouped together and reported as ‘‘interpersonal violence’’[

2] [

1].

Interpersonal violence includes acts of violence and intimidation that occur between family members, between intimate partners, or between individuals, whether or not they are known to one another, and where the violence is not specifically intended to further the aims of any group or cause [

5].

Violent behavior is provoked by a complex interaction of physiological, psychological, and environmental factors. From a public health approach, an ecological model is commonly used to determine risk factors for interpersonal violence [

6]. The model considers factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels: At the individual level, gender and age are key risk factors. One ‘s age and gender are associated with a greater or lesser propensity for involvement in interpersonal violence. For example, vulnerability to interpersonal violence changes over the life cycle; youth have the highest propensity to perpetrate or be victimized by interpersonal violence, but the elderly are also vulnerable to interpersonal violence. Young men are most vulnerable as both perpetrators and victims of interpersonal violence [

7]. Alcohol or substance use is another major risk factor that influences interpersonal violence at an individual level [

1]. The interpersonal level focuses on an individual’s relationship with peers, intimate partners, and family members. The community level examines and seeks to identify settings/ locations with a high prevalence of interpersonal violence and the characteristics of these locations that increase the risk of interpersonal violence. Lastly, the societal level looks at the cultural norms, gender, and economic inequality that give rise to interpersonal violence in society [

1] [

7].

About 4400 people die every day because of intentional acts of self-directed, interpersonal, or collective violence. Many thousands more are injured or suffer other non-fatal health consequences because of being the victim or witness to acts of violence. Additionally, tens of thousands of lives are destroyed, families are shattered, and huge costs are incurred in treating victims, supporting families, repairing infrastructure, prosecuting perpetrators, or as a result of lost productivity and investment [

1]. In the 53 countries of the WHO European Region, violence kills about 160,000 people each year, and of these, around 31,000 die from interpersonal violence [

8].

Deaths are just the tip of the iceberg and for every death, there are numerous admissions to hospital and emergency departments. The clinical pyramid for all types of violence has not been properly estimated, but interpersonal violence is thought to result in at least one million injuries severe enough to warrant medical attention, resulting in high costs, and competing for already over-stretched resources [

1].

Injuries and violence are significant causes of death and the burden of disease in all countries. They are not evenly distributed across or within countries – some people are more vulnerable than others depending on the conditions in which they are born, grow, work, live and age. For instance, in general, being young, male and of low socioeconomic status all increase the risk of injury and of being a victim or perpetrator of serious physical violence [

9].

Still, to understand the population burden of exposure to violence and the sub-populations who are at elevated risk, it is important to know the prevalence and socio-demographic factors associated with exposure to interpersonal violence among both men and women [

10] [

11] [

12]

Most research on the prevalence of interpersonal violence has focused on violence against women and men’s perpetration, in part because of the greater burden of certain forms of violence for women and the greater adverse effects of violence on women’s mental and physical health [

13] [

14] [

15].

But it is also important to know the impact of other types of violence with long-term consequences for individuals and society, such as child or elder maltreatment. These types of violence often occur in the home and remain hidden because they are rarely reported to the authorities but victims can access to healthcare system to receive help.

Global policies state the urgent need to address domestic violence and abuse. This problem demands a complex inter-sectoral approach underpinned by a strong universal health system capacity to identify and tailor responses to the circumstances of affected families. The World Health Organization has identified the crucial role of an effective health system in reducing the extensive damage from violence, especially for children [

15] [

16] [

17] [

18].

General practice, antenatal clinics, community child health and emergency departments are key places for intervention for violence, as health practitioners are the major professional group to whom patients want to disclose [

19]. Only a minority of women, men and/or children exposed to violence and abuse are recognized in health care settings[

18].However, we know that patients want to be asked directly about violence by supportive practitioners, typically making multiple visits before disclosure[

19]. Unfortunately, when patients do disclose, there is evidence that health professionals often lack the essential skills and experience to respond appropriately[

17] .Much less is known about health practitioners’ capacity to identify and respond to children exposed to violence or to men who experience or use violence in their intimate relationship [

20] [

21].

Therefore, healthcare professionals in emergency departments are crucial to detect violence and provide information on the nature of an injury, how it was sustained, and when and where the incident occurred. They are the first step in healthcare system to obtain more knowledge about both the prevalence and health consequences of interpersonal violence and as consequence should have an adequate training to suspect violence[

22].

As part of adequate training, it is important to carry out surveys/registries that can provide detailed information about the victim or perpetrator when visiting emergency departments, as well as his or her background, attitudes, behaviors, and possible previous involvement in violence. Such sources can also help uncover violence that is not reported to the police or other agencies and can provide valuable information to prevent violence[

23].

Our hospital has, since 2009, an official registry to report violence or abuse when healthcare professionals suspect them. We aim to share the information collected in the registry throughout these years to expand the available knowledge and implement preventive strategies. Our aim in this article is to assess healthcare professionals’ recognition of types of interpersonal violence among patients admitted to the hospital including childhood and adulthood both, men and women, and factors associated with exposure to violence.

2. Materials and Methods

Since 2009 an internal registry of interpersonal violence is conducted in “Hospital Clinico Universitario San Carlos” (Third level hospital), located in Madrid.

As a part of usual routine practice in whole hospital departments, an approved questionnaire focus in abuse/violence, is administered to admitted patients with suspicion of interpersonal violence; the questionnaire was approved by health authorities in the hospital in 2009. The source of information for this study was the data extracted from the questionnaire since 2009 to 2022.

All admitted patients with suspicion of violence were included, there were not exclusion criteria regarding age or gender.

The questionnaire included the following variables: age, gender, age, country of birth, race, date of abuse/violence, date of medical attention, violence background, reason for consultation, specialty which attend, risk factors, vulnerability of the victim, disability, cognitive impairment, current pregnancy, psychiatric diseases, physical or psychiatric dependence, relationship with violence perpetrator, coexistence with perpetrator type of violence(physical violence, sexual violence, economic violence, negligence, chemical submission, mutilation, harassment, others or combinations of violence) previous assaults, companion, current diagnosis, emission of injuries report, taking biological samples under chain of custody, contact with health authorities, assessment by forensic doctor, social services intervention, healthcare personnel who carry out the registration, professional which attend patient, patient referral professional, judicial protection measures, protective measures in the hospital.

Descriptive analyses were assessed. The numerical variable was given a mean ± standard deviation, and the categorical variable was given a frequency. Student’s t-test, and Mann Whitney was used to compare whether the means (of quantitative variables)and a Chi-square test of proportions (of categorical variables) A p-value of 0.05 was used as a marker of statistical significance. Analyses were performed with statistical software XLSTAT version 2023.2.1413 Lumivero (2024). XLSTAT statistical and data analysis solution. New York, USA.

https://www.xlstat.com/es

3. Results

The questionnaire was completed for a total of 1284 patients suspected of suffering interpersonal violence. Most of the suspicions were attended in the emergency department (83.4%), 8.4% during hospitalization, and 8.2% in external consultations.

During this time 1600000 patients were admitted in the emergency department, and interpersonal violence was suspected in 0.06 %; in outpatient clinics (12320000 patients) the percentage of suspicions was 0.0008%, while among hospitalized patients (420000 patients) the percentage was 0.02%.

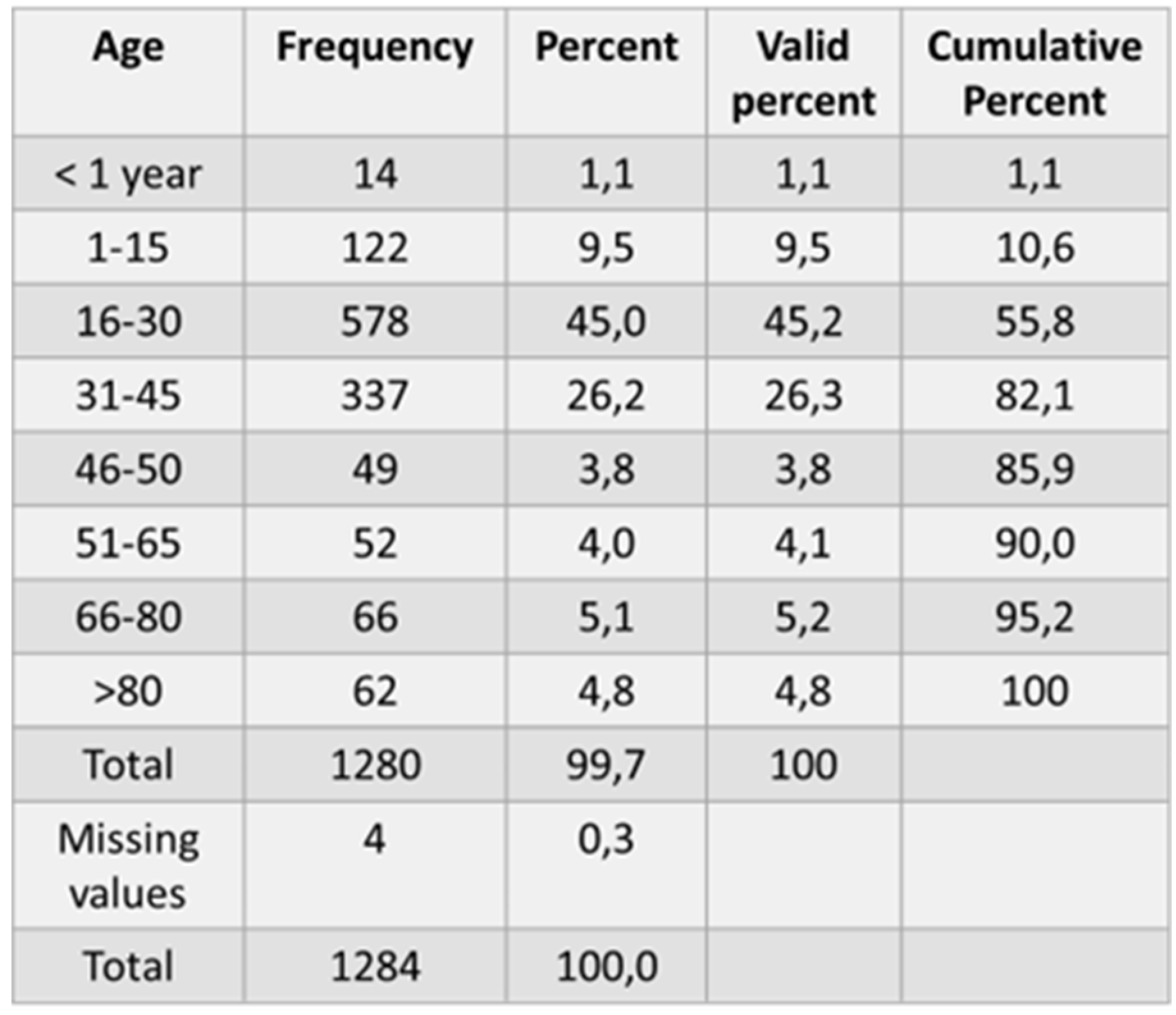

Of the total patients, 80,8% were women and 19.2% were men. The mean age was 33.19 years old (Range 0-99; SD 19.83). Subjects were stratified into groups: 13.9% <18 years old; 75.9% in the group 18-64 and 10.2% in the group ≥ 65 years old.

The distribution between each age group is shown in

Table 1. Most of the patients are in group 16-30 years old:45.2%, followed by the group 31-45 with 26.3%.

Regarding the site of birth, 62.2% (786) were Spanish, followed by patients from South America 19.7%(249) and patients from other European countries (6.2%) the remaining % includes people from other countries such as Africa (3.7%), Central America (3.5%), Antilles (2.3%), Asia (1.3%), North America (1%) and Oceania (0.2%).

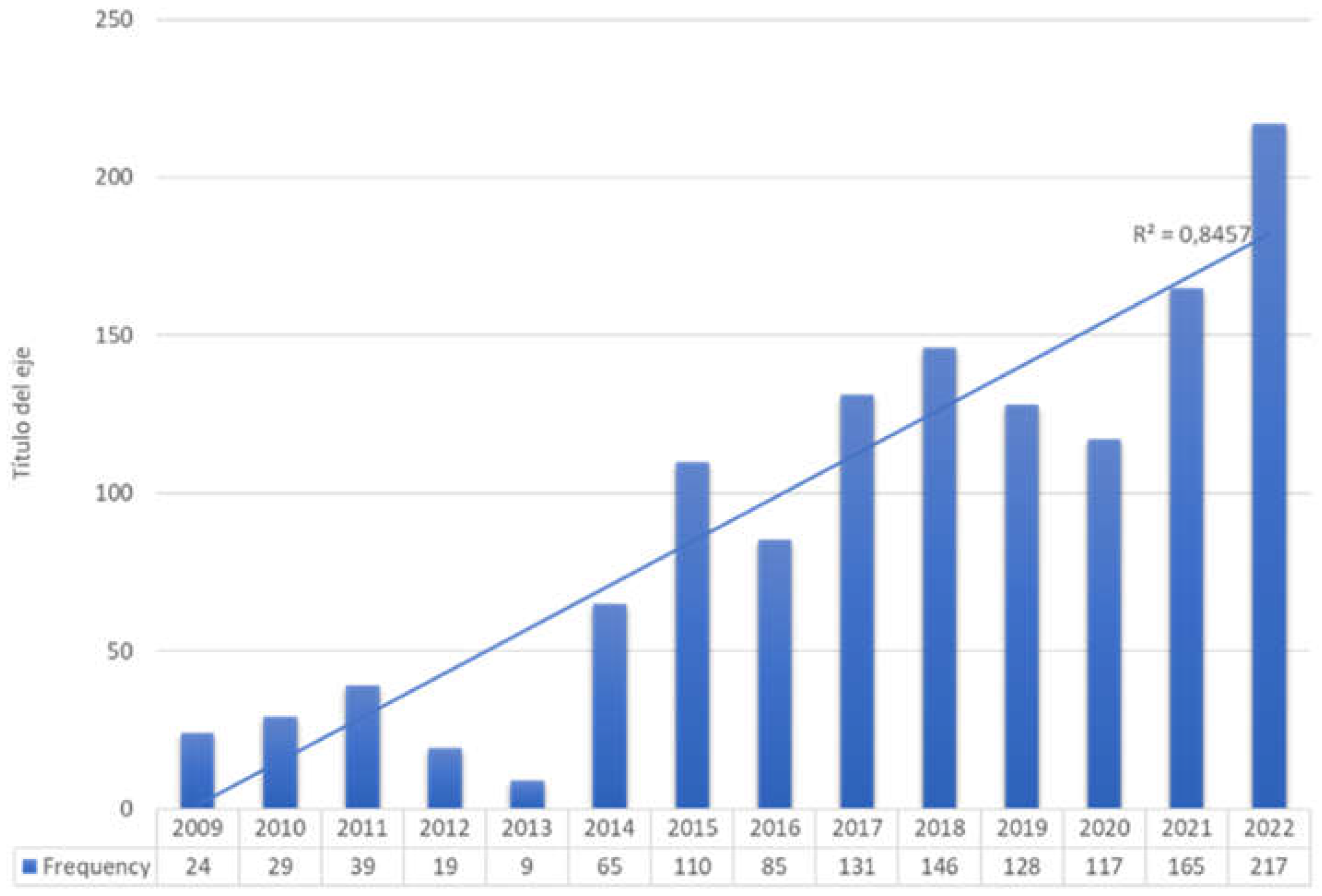

A growing number of patients suffered from violence were reported every year since 2009, showing a linear correlation (R2= 0.8457); 16.9% (217) were notified in 2022, which clearly contrast with the number in 2009: 24 patients (1.9%). Distribution among years is showed in

Figure 2

Analyzing violence risk factors as gender, we observed that most of the patients were women (80.8%), and 5.6 % (58) of them were pregnant; regarding the group of age 18,9 %(243) of patients were below 18 or over 80 years old; 10, 2% had a disability or physical dependence and 11.3% had cognitive impairment, depression or other psychiatric diseases.

In terms of the patients ‘relation with the aggressor, 568 patients (44,2 %) did not have any relationship with the perpetrator; 55.8% of patients had some relationship with the aggressor, in 25.2% of cases were their couples; 14,7 % (189) receive maltreatment by other family members; in 8.2% the perpetrators were acquaintances or friends; 6.5 % receive violence from their ex-partners and 1,2 % from their caregivers.

Surprisingly 29.4 % of patients lived with the aggressor 3.8% lived and were accompanied to the consultation by their aggressor and 66% of patients did not maintain any contact with the perpetrator.

Physicians were the health professionals who most frequently completed the registry at 47.6% (607 registries), followed by social workers at 36.6%, psychologists at 12,7 % of cases, and nurses at 3.1%. In 65.5% of cases, an injury report was issued.

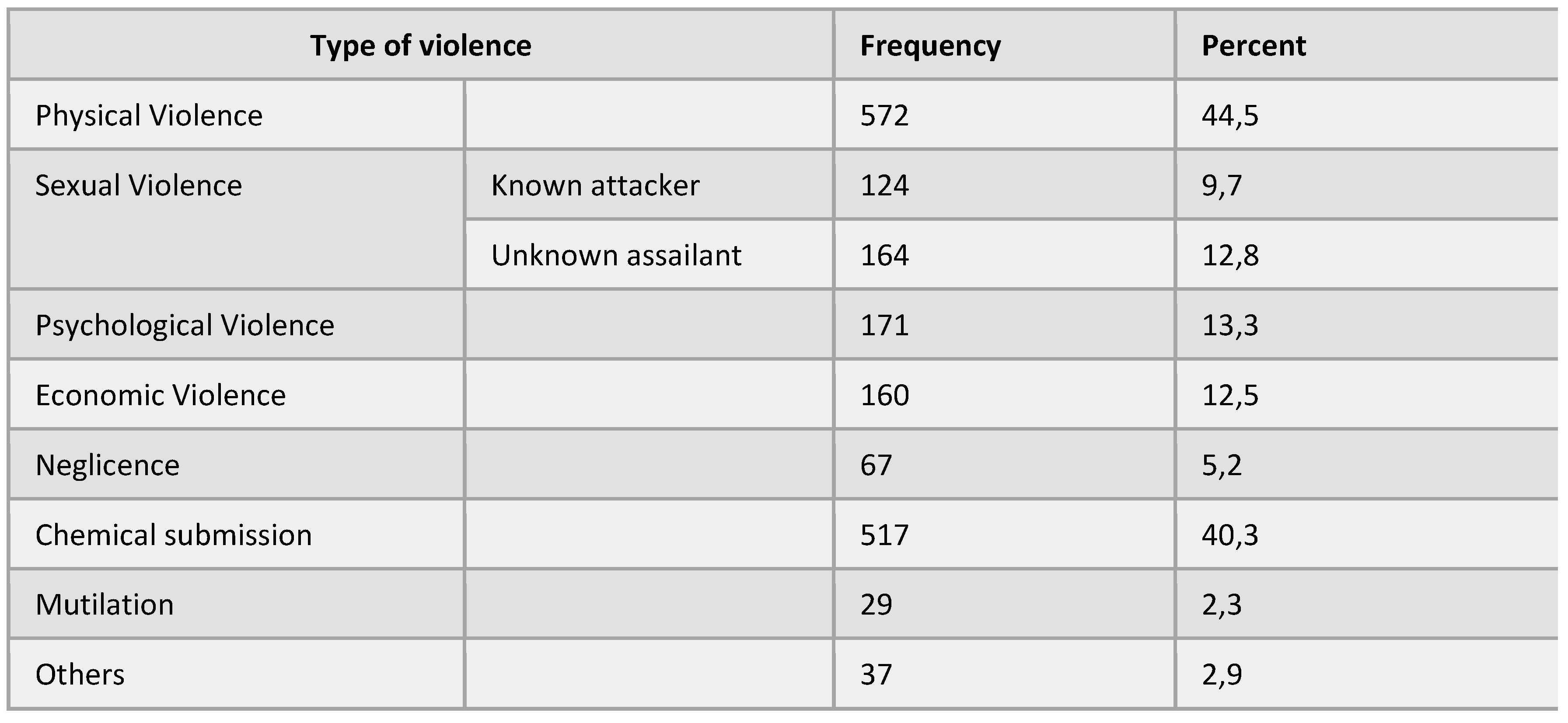

A description of types of violence is specified in

Table 2. 44.5% of victims suffered physical violence, 22,4% (288 patients) sexual violence (of whom 12,8% from an unknown person and 9.7% from a known person),13.3% suffered from psychological violence and 12.5% economic violence. Negligence was observed in 67 patients (5.2%). 517 patients (40.3%) suffered from chemical submission and 29 (2.3%) mutilation.

A combination of different types of violence was observed in 36.3% (466 patients). Of whom 382 (29.8 %) suffered 2 types of violence. The most frequent type of combination was sexual violence with chemical submission (107 patients)

4. Discussion

The study employs an approved questionnaire within our hospital aimed at detecting victims of interpersonal violence. Healthcare professionals complete it when they suspect abuse, regardless of whether it is verifiable. Unlike other studies, our questionnaire encompasses a wide range of patients collected over 13 years [2009-2022].

Comparing our results with those of other studies in the literature is challenging, since some studies that collect data from violence registries are focused only on emergency departments [

6,

24,

25,

26,

27], collect data on both victims and perpetrators [

6,

27,

28,

30] or gather data through surveys administered over short periods of time [

26] focusing on specific population groups, such as young people [

25],consequently, results may vary considerably.

Moreover, studies conducted in countries differing significantly from ours make extrapolating results challenging due to social, cultural, gender, and economic differences that contribute to interpersonal violence in society [

7].

The percentage of suspected victims of interpersonal violence across the entire hospital was 0.008%, although extrapolated to the population treated in the emergency room it rose to 0.06%. We have not found data on the percentage of suspicion in other hospitals, since there are no similar questionnaires in other similar centers in our setting.

The higher percentage of suspicion in the emergency department suggests that professionals there are better trained to identify abuse. This aligns with studies indicating that health professionals’ training increases suspicion levels [

28]. However, while literature reviews suggest that enhanced training may improve professionals’ knowledge and attitudes, evidence regarding its impact on recognizing cases is inconclusive. Further randomized and blinded studies are needed to ascertain training’s effectiveness in detecting interpersonal violence [

22].

Our results indicate that over 80% of victims were women, consistent with other studies and official agency reports [

15] [

26]. However, this differs from studies in low and middle-income countries where men are more frequently victims of aggression [

6] [

24] [

27].

The mean age of victims was 33.19 years, with the majority falling in the 16-30 age group, consistent with other studies [

27]. A systematic review estimates that the risk of violence is also high between ages 31 and 40 [

29], corroborating data on victims resulting in death in our country, which places the age between 26 and 45 years [

30]. However, these data pertain solely to female victims of domestic violence.

Most of the victims were Spanish, followed by patients coming from South America, this is consistent with the series of data on deaths caused by domestic violence offered annually by the Council of the Judiciary in Spain [

30] The socio-economic status of victims concerning nationality remains unknown, potentially influencing interpersonal violence risk. At the individual level, empirical evidence suggests a link between poverty and higher levels of interpersonal violence [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36], particularly concerning child abuse [

1]. However, this relationship is complex often compounded by economic inequality, economic hardship in areas characterized by both significant poverty and wealth serves as a stressor and, we suspect, contributes to the occurrence of violence.

Policies promoting social awareness to change norms condoning violence, particularly against women, may explain the decrease in violence numbers over time [

32,

37]. However,our data reveal a linear correlation in the number of victims of violence over the years, suggesting that prevention efforts are not yielding the expected results. the explanation for this increase could be related to greater awareness among health care professionals [

38].

In the sample, most of the aggressions came from people close to the victim, more than 30% were attacked by their partner or ex-partner and more than 30% by relatives, friends, acquaintances, or caregivers, surprisingly almost 30% of victims lived with the aggressor even in a small number of cases the perpetrator accompanied them to the medical consultation. This fact has several interpretations, the victims of interpersonal violence remain in abusive relationships due to their desire to keep their family together for fear of losing their children [

39] [

40], as well as insecurity, lack of family and social support [

39,

41] [

42] and fear of being killed [

43] [

44]. In addition to these motives is the constant intimidation and belittlement that the partners carry out, by diminishing the victim as a person, making her feel inferior [

45].

In our study, most of the questionnaires were completed by physicians, followed by social workers and psychologists, and to a lesser extent by nurses, This is in contrast to studies in other media, where the responsibility for the screening was relegated to the triage nurse [

26]. A qualitative meta-analysis analyzed physicians’ barriers to recognizing violence, The most frequent reasons were : limited time with patients, lack of privacy, lack of management support, and a health system that fails to provide adequate training, policies and response protocols, and resources and normalization of violence, only presents in certain types of women, women will lie or are not reliable [

46].

In this study we show, in

Table 2, a summary of the types of violence suffered by victims, we will not discuss them in this article, we offer the results just for information, a more detailed analysis of the data will be carried out and will be provided in a future publication.

5. Conclusions

Routine screening in a hospital of patients suspected of interpersonal violence, could increase sensitivity to the needs of those who have experienced abuse.

A routine questionnaire could increase healthcare professionals’ awareness. The level of suspicion of interpersonal violence must be increased in all hospital departments in addition to emergency rooms.

Well-trained professionals are crucial to prevent and provide safety of those who are victimized.

Injury prevention programs can then be instituted in the community with the collaborative efforts of health care providers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Andrés Santiago-Sáez, Montserrat Lazaro del Nogal Patricia Villavicencio Carrillo, María Teresa Martín Acero, Cesáreo Fernández Alonso, Raquel Lana Soto; methodology Andrés Santiago-Sáez ; software, Andrés Santiago-Sáez.; validation:Andrés Santiago-Sáez, Montserrat Lazaro del Nogal Patricia Villavicencio Carrillo, María Teresa Martín Acero, Cesáreo Fernández Alonso, Raquel Lana Soto; methodology: Andrés Santiago-Sáez; formal analysis: Andrés Santiago-Sáez; data curation, Andrés Santiago-Sáez, Montserrat Lazaro del Nogal Patricia Villavicencio Carrillo, María Teresa Martín Acero, Cesáreo Fernández Alonso, Raquel Lana Soto; methodology Andrés Santiago-Sáez ; writing—original draft preparation review and editing: Andrés Santiago-Sáez, Montserrat Lazaro del Nogal, Patricia Villavicencio Carrillo, María Teresa Martín Acero, Cesáreo Fernández Alonso, Raquel Lana Soto; supervision: Andrés Santiago-Sáez.; funding acquisition, Andrés Santiago-Sáez. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundación para la Investigación Hospital Clínico San Carlos, grant number CM 2023-3-052 and The APC was funded by Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval because data were obtained from retrospective archive and were properly anonymized.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not obtained because data were anonymized.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet Lond Engl. 2002 Oct 5;360(9339):1083–8.

- Ferris LE. World Report on Violence and Health. Can J Public Health Rev Can Santé Publique. 2002 Nov;93(6):451.

- Healthline [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 29]. What’s the Difference Between Violence and Abuse? Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/what-is-the-difference-between-violence-and-abuse.

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases.

- Davis KH, Folsom RE, Carroll FI, Cooley PC, Retzlaff LM, Weeks MF, et al. The Economic Dimensions of Interpersonal Violence. 2004 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Jan 29]; Available from: https://www.rti.org/publication/economic-dimensions-interpersonal-violence.

- Sheikh S. Characteristics of interpersonal violence in adult victims at the Adult Emergency Trauma Centre (AETC) of Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital. Malawi Med J. 2020 Mar 31;32(1):24–30. [CrossRef]

- Willman A, Makisaka M. INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE PREVENTION A Review of the Evidence and Emerging Lessons. 2010 Jun 11;

- Global Health Estimates: Life expectancy and leading causes of death and disability [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates.

- 9789240047136-eng.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/361331/9789240047136-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Simmons J, Wijma B, Swahnberg K. Lifetime co-occurrence of violence victimisation and symptoms of psychological ill health: a cross-sectional study of Swedish male and female clinical and population samples. BMC Public Health. 2015 Sep 28;15:979. [CrossRef]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):245–58.

- The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010-2012 State Report.

- Why Do Some Men Use Violence Against Women and How Can We Prevent it? | Office of Justice Programs [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/why-do-some-men-use-violence-against-women-and-how-can-we-prevent.

- Fulu E, Miedema S, Roselli T, McCook S, Chan KL, Haardörfer R, et al. Pathways between childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, and harsh parenting: findings from the UN Multi-country Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health. 2017 May;5(5):e512–22. [CrossRef]

- Global and regional estimates of violence against women [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241564625.

- Hegarty K, Glasziou P. Tackling domestic violence: is increasing referral enough? Lancet Lond Engl. 2011 Nov 19;378(9805):1760–2.

- Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241548595.

- García-Moreno C, Hegarty K, d’Oliveira AFL, Koziol-McLain J, Colombini M, Feder G. The health-systems response to violence against women. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015 Apr 18;385(9977):1567–79. [CrossRef]

- Feder GS, Hutson M, Ramsay J, Taket AR. Women exposed to intimate partner violence: expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: a meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jan 9;166(1):22–37.

- Hegarty K, McKibbin G, Hameed M, Koziol-McLain J, Feder G, Tarzia L, et al. Health practitioners’ readiness to address domestic violence and abuse: A qualitative meta-synthesis. PLoS ONE. 2020 Jun 16;15(6):e0234067. [CrossRef]

- Hegarty K, Taft A, Feder G. Violence between intimate partners: working with the whole family. BMJ. 2008 Aug 4;337:a839. [CrossRef]

- Kalra N, Hooker L, Reisenhofer S, Di Tanna GL, García-Moreno C. Training healthcare providers to respond to intimate partner violence against women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 May 31;5(5):CD012423. [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence a global public health problem. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2006 Jun;11(2):277–92.

- d’Avila S, Campos AC, Bernardino Í de M, Cavalcante GMS, Nóbrega LM da, Ferreira EF e. Characteristics of Brazilian Offenders and Victims of Interpersonal Violence: An Exploratory Study. J Interpers Violence. 2019 Nov 1;34(21–22):4459–76.

- Mollen CJ, Fein JA, Vu TN, Shofer FS, Datner EM. Characterization of Nonfatal Events and Injuries Resulting from Youth Violence in Patients Presenting to an Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003 Dec;19(6):379. [CrossRef]

- Krimm J, Heinzer MM. Domestic violence screening in the emergency department of an urban hospital. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002 Jun;94(6):484–91.

- Tingne CV, Shrigiriwar MB, Ghormade PS, Kumar NB. Quantitative analysis of injury characteristics in victims of interpersonal violence: An emergency department perspective. J Forensic Leg Med. 2014 Aug 1;26:19–23. [CrossRef]

- Lo Fo Wong S, Wester F, Mol SSL, Lagro-Janssen TLM. Increased awareness of intimate partner abuse after training: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2006 Apr;56(525):249–57.

- Fuentes JMD, Leiva PG, Casado IC. VIOLENCIA CONTRA LAS MUJERES EN EL ÁMBITO DOMÉSTICO: CONSECUENCIAS SOBRE LA SALUD PSICOSOCIAL. An Psicol Ann Psychol. 2008;24(1):115–20.

- C.G.P.J | Temas | Violencia doméstica y de género | Actividad del Observatorio | Informes de violencia doméstica y de género | Comparativa Violencia de Género-Violencia Doméstica Íntima [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 13]. Available from: https://www.poderjudicial.es/cgpj/es/Temas/Violencia-domestica-y-de-genero/Actividad-del-Observatorio/Informes-de-violencia-domestica-y-de-genero/Comparativa-Violencia-de-Genero-Violencia-Domestica-Intima.

- Asal V, Brown M. A Cross-National Exploration of the Conditions that Produce Interpersonal Violence. Polit Policy. 2010;38(2):175–92. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Heise L, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Watts C. Violence Against Women. Science. 2005 Nov 25;310(5752):1282–3.

- Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. The Lancet. 2002 Apr 20;359(9315):1423–9. [CrossRef]

- Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Campbell J. Individual and Contextual Determinants of Domestic Violence in North India. Am J Public Health. 2006 Jan;96(1):132–8. [CrossRef]

- Toward a Biopsychosocial Model of Domestic Violence | Office of Justice Programs [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/toward-biopsychosocial-model-domestic-violence.

- Simon TR, Anderson M, Thompson MP, Crosby AE, Shelley G, Sacks JJ. Attitudinal Acceptance of Intimate Partner Violence Among U.S. Adults. Violence Vict. 2001 Jan 1;16(2):115–26. [CrossRef]

- WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: summary report [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9241593512.

- Elliott L. Interpersonal Violence. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Oct;18(10):871–2.

- Guedes RN, Silva ATMC da, Coelho E de AC, Silva CC da, Freitas W de MF e. A violência conjugal sob o olhar de gênero: dominação e possibilidade de desconstrução do modelo idealizado hegemonicamente de casamento. Online Braz J Nurs Online [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2024 Feb 15]; Available from: http://www.objnursing.uff.br/index.php/nursing/article/view/j.1676-4285.2007.1103/261.

- Kelmendi K. Domestic violence against women in Kosovo: a qualitative study of women’s experiences. J Interpers Violence. 2015 Feb;30(4):680–702.

- 243016308007.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 15]. Available from: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2430/243016308007.pdf.

- Help-Seeking Behavior Among Abused Immigrant Women: A Case of Vietnamese American Women - Hoan N. Bui, 2003 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 15]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1077801202239006. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh HF, Feng JY, Shu BC. The Experiences of Taiwanese Women Who Have Experienced Domestic Violence. J Nurs Res. 2009 Sep;17(3):153. [CrossRef]

- Pereira ME, Azeredo A, Moreira D, Brandão I, Almeida F. Personality characteristics of victims of intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2020 May 1;52:101423. [CrossRef]

- Yoshihama M, Mills LG. When is the personal professional in public child welfare practice?: The influence of intimate partner and child abuse histories on workers in domestic violence cases. Child Abuse Negl. 2003 Mar 1;27(3):319–36. [CrossRef]

- Hudspeth N, Cameron J, Baloch S, Tarzia L, Hegarty K. Health practitioners’ perceptions of structural barriers to the identification of intimate partner abuse: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Jan 22;22(1):96. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).