Introduction

Occupational violence in paramedicine is increasingly recognized as a growing and complex - yet underreported [1-3] - problem, creating the potential for significant harm [4-6]. There is now abundant research indicating that paramedics are regularly exposed to violence [1-4,7-11], experience high rates of physical injuries - often surpassing injury rates for other public safety personnel, like firefighters [

12] - and that exposure to violence has significant impacts on mental health, job satisfaction and well-being among paramedics [5,7,11,13-15]. Given high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder [

16], burnout [

17,

18], depression and anxiety [

16,

19] among paramedics, exposure to violence has the potential to compound an existing mental health crisis in the profession [

20] and worsen the workforce shortages being experienced within healthcare more broadly [

21,

22].

There is, then, a pressing need to develop strategies that both identify and mitigate the risk of violence during 9-1-1 calls, but any meaningful effort at risk mitigation must be informed by accurate event-level data about violent encounters. Unfortunately, there is widespread recognition that violent encounters are chronically underreported, with only the most serious (i.e., those resulting in significant physical injuries) documented through formal incident reporting processes [1-3]. The reasons for this are multifaceted, but commonly include administrative barriers, such as overly onerous incident reporting processes [

7], underpinned by an organizational culture that considers violence “part of the job” [

23] and not worth reporting. In a 2014 study of paramedics from two Canadian provinces, Bigham and colleagues found that paramedics rarely reported incidents of violence to police or service leadership teams and lacked culturally acceptable reporting pathways [

7]. Among other things, Bigham et al. suggested that reporting might be improved if paramedics were involved in the development of purpose-built incident reporting processes [

7].

The External Violence Incident Report

As part of a broader workplace violence prevention program within a paramedic service, our team developed a new, streamlined violence reporting process. The External Violence Incident Report (EVIR) is a purpose-built incident report developed in consultation with paramedics to gather quantitative and qualitative data about violence, including the type (e.g., verbal abuse, physical assault) and source (e.g., patient, bystander) of violence during 9-1-1 calls. Additional details are provided below.

In contrast to survey methods [4,7,24-26] or injury database searches [

12,

27,

28] that have been the mainstay of research on violence against paramedics, the collection of event-level data about violent encounters as part of routine clinical and administrative documentation allows for more granular epidemiological study of the problem. This is particularly important in developing upstream risk stratification strategies. Therefore, leveraging this novel incident reporting process, our objective was to identify types of 9-1-1 calls that are associated with an increased risk of violence against paramedics.

Materials and Methods

Overview

We conducted this study as part of a larger research program on violence against paramedics, and we detailed our overall approach in an earlier publication [

29]. For this study, we retrospectively reviewed electronic Patient Care Records (ePCRs) and External Violence Incident Reports (EVIRs) filed over a two-year period since the launch of the new reporting process in a single paramedic service in Ontario, Canada. Using logistic regression analyses, our objectives were to identify covariates in ePCR data that are associated with an increased risk of any violence and (as a subgroup) of a physical or sexual assault on a paramedic.

Setting and Context

This research is situated in the Regional Municipality of Peel in Ontario, Canada. Peel Regional Paramedic Services (PRPS) is the sole provider of land ambulance and paramedic services to the municipalities of Brampton, Mississauga, and Caledon, collectively encompassing the Region of Peel. The paramedic service is publicly funded, provincially regulated, and separate from police and fire services. PRPS serves a population of approximately 1.3 million residents across a mixed urban/suburban geography of 1,200km2 with a complement of approximately 750 Primary and Advanced Care Paramedics who respond to an average of 130,000 emergency calls per year - collectively making the service the second largest in the Province of Ontario by staffing and call volume.

The introduction of the new reporting process occurred alongside a suite of initiatives as part of a larger workplace violence prevention program. This included (among other things), new policies and procedures, patient restraint equipment, and a public position statement of ‘zero tolerance’ for violence against paramedics.

Data Collection

We described the development of the EVIR in an earlier publication [

30]. Briefly, the development phase involved an extensive stakeholder consultation, gap analysis, and pilot testing process. The result was an incident report built to gather comprehensive quantitative and qualitative information about violent encounters with the public during 9-1-1 calls. The report primarily makes use of drop-down menu selection questions to gather information about the type (e.g., verbal abuse, threats, sexual harassment, or physical or sexual assault), circumstances (e.g., alcohol or drug intoxication, mental health crisis, or cognitive impairment), and source (e.g., patient, family member, bystander, etc.) of violence, with one free-text box in which paramedics can type a detailed narrative description of the violent encounter. The form is embedded within the ePCR software. Provincial documentation standards require paramedics to complete an ePCR after each 9-1-1 call and additionally mandate the completion of incident reports in unusual circumstances, such as situations that involve a risk to the patient or paramedic. The EVIR constitutes an incident report under these standards and the software reminds paramedics to complete an EVIR when filing an ePCR if they experienced any form of violence during the call. The EVIR in its entirety is available as supplementary material in

Figure S1.

The ePCRs, meanwhile, gather administrative and clinical data about the call and the treatment provided to patients. For this study, we were interested in the following fields from all ePCRs filed during the study period: dispatch priority (e.g., urgent, non-urgent), location type code (e.g., residence, street/intersection, etc.), primary presenting problem code (e.g., altered level of consciousness, shortness of breath, etc.), patient acuity via the Canadian Triage Acuity Scale (CTAS) [

31], patient age and sex, and all call event times (e.g., call received, crew notified, etc.). When an EVIR is filed, these data points are automatically pulled from the corresponding ePCR into the body text of the violence report. The ePCR software incorporates compliance rules for documentation that minimize missing data by making most fields mandatory, depending on the 9-1-1 call type; in practical terms this afforded a very low (i.e., near zero) rate of missing information.

Our data collection window spanned a two-year period from February 1, 2021 (when the reporting process was launched) through January 31, 2023. We abstracted the administrative data points described above from all ePCRs filed during the study window and all fields from the EVIR where one was filed for a particular service call. Although not primarily intended for research, the EVIR includes a passive consent process where the documenting paramedic can opt out of having a particular report used for research purposes by ticking a box; in these cases, the reports were excluded.

Measures and Outcomes

Our list of covariates included the day of week, time of day, dispatch priority code, call location code, primary presenting problem code, patient acuity level, and patient gender and age. Paramedics in our service normally work 12-hour day or night shifts, with additional staff scheduled during ‘peak’ demand periods; however, for our analysis we defined three non-overlapping 8-hour buckets: day (0600-1359 hours), afternoon (1400-2159 hours), and overnight (2200-0559 hours) shifts, respectively. Several of the covariates are multi-level categorical variables, including the call location code (26 levels; e.g., residence, street, restaurant) and primary presenting problem code (55 levels; e.g., cardiac arrest, shortness of breath, unconscious).

Our primary outcome was whether an EVIR was filed for a particular 9-1-1 call (‘any violence’), with physical or sexual assault on a paramedic (‘any assault’) as our secondary outcome.

Analysis

We used descriptive and summary statistics to report on the characteristics of the data, including the types of violence reports included in the study. Using complete case analysis, we used logistic regression to estimate the probability of our primary and secondary outcomes using the covariates described above, as these are characteristics of 9-1-1 calls that are generally available to the paramedics at the point of dispatch.

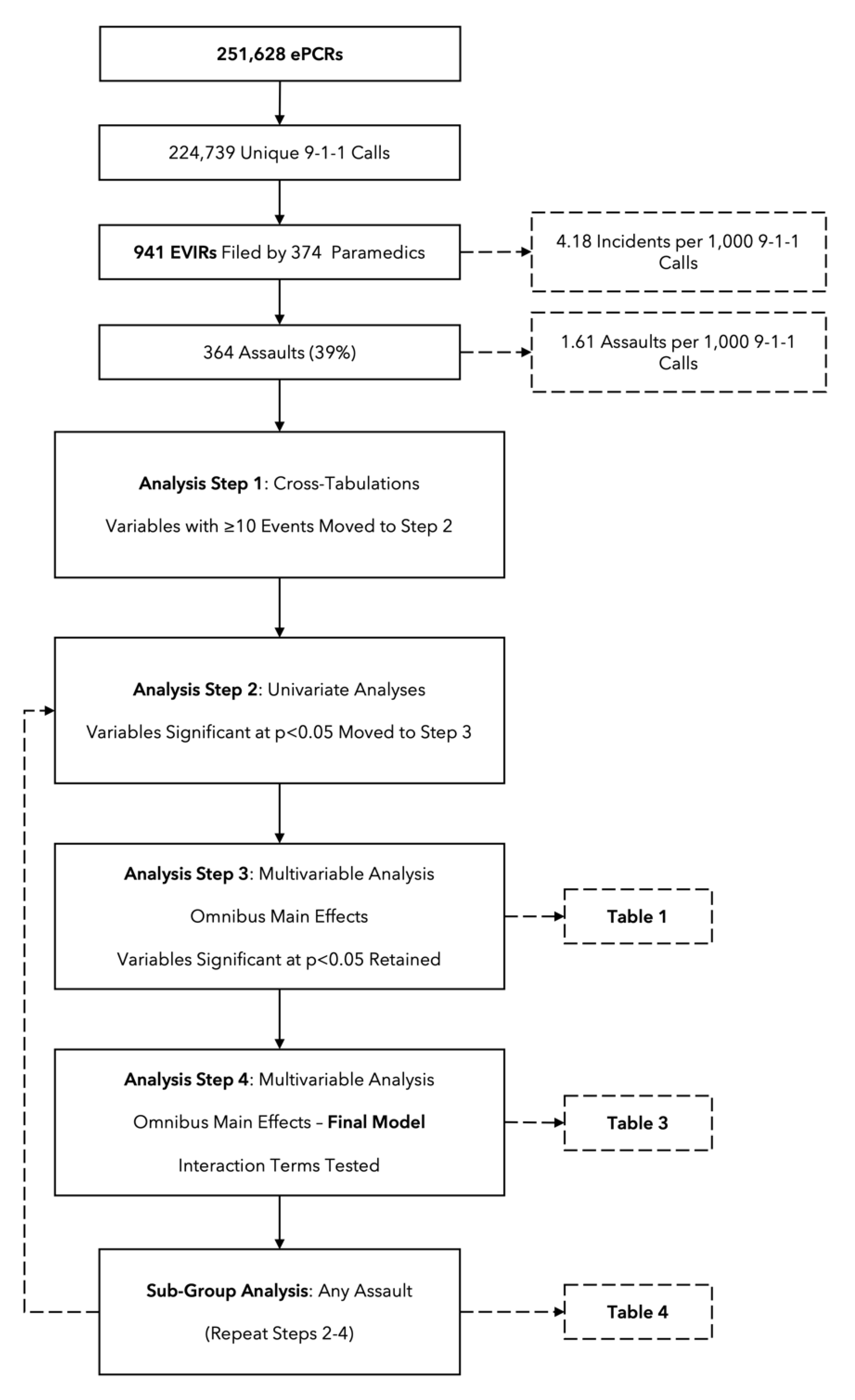

An overview of our analytical approach is provided in

Figure 1. Because of the large number of variables (and levels of variables) included in the analysis, our approach to modeling involved several iterative steps to first reduce the number of covariates that would be included in the final models. First, we ran cross-tabulations on each covariate to identify the number of EVIRs associated with the variable and each of its levels (where applicable); covariates with observed frequencies of at least 10 events were retained for inclusion. Next, and where applicable, we grouped similar variable levels together (e.g., ‘apartment/condo’ and ‘house’ was reclassified as ‘private residence’); in this manner, ‘call location code’ was reduced from 26 levels to 7 in a new composite ‘high risk call location’ variable. Primary presenting problem was similarly reduced from 56 levels to 8 in a new ‘high risk problem’ variable. We did this to improve model stability while preserving statistical power. A step-by-step accounting of this reclassification process is offered as supplementary material in

Table S1.

With variable reclassifications complete, we ran univariate analyses to test the association between each new variable and our primary outcome (‘any violence’). Covariates or levels of categorical variables that did not reach significance at p<0.05 were dropped. Significant covariates were then entered as a group into a new model to test the main effects. Again, covariates or levels of categorical variables that did not retain significance at p<0.05 at this stage were dropped. Finally, we constructed interaction terms of significant covariates that had plausibility for presenting an increased risk of violence and introduced these terms individually into our adjusted model. This process was repeated for our secondary outcome of any physical or sexual assault.

The principal assumptions of concern for this analysis were collinearity and overfitting; our approach was intended to minimize both risks by collapsing related variables and filtering covariates through a robust selection process. Only cases with complete data for the variable of interest were used. In constructing our models, our interest was in the significance of the individual covariates rather than the predictive capacity of the model as a whole. Our threshold for significance of the individual covariates was a p-value less than 5% and 95% confidence intervals that excluded the null.

Results

Overview

Over the two-year study period, the paramedic service generated a total of 251,628 ePCRs. After excluding duplicate forms filed for the same incident, this left 224,739 unique 9-1-1 calls for analysis, with 941 EVIRs filed by 374 paramedics for an overall rate of violence of 4.18 incidents per 1,000 9-1-1 calls. Of the reports, 39% (n=364) documented some form of physical or sexual assault, either alone or in combination with other forms of violence, yielding a rate of 1.61 assaults per 1,000 calls. In total, 81 incidents resulted in a paramedic being physically harmed during the encounter.

The majority (n= 697;74%) of the violence occurred at the emergency scene and patients were cited as the perpetrator in 83% of cases (n=781). Alcohol or drugs (n=461; 49%) or mental health concerns (n=317; 37%) were frequently listed as contributing circumstances. The reports were fairly uniformly distributed across days of the week, with the lowest proportion (12%) on Monday and the highest (16%) on Tuesday and no statistically significant differences between days (p=0.618). The highest proportion of reports (47%) was filed during the afternoon shift.

Univariate Analyses

In our univariate analyses, dispatch priority (urgent), location code (residence, store, long-term care home, hotel, street, or restaurant), shift (afternoon and overnight), and several primary presenting problems (e.g., intoxication, mental health, trauma, chest pain, and altered mental status) were all individually associated with an increased risk of any violence. Compared to ‘non-urgent’ acuity (CTAS 5), patients requiring resuscitation (CTAS 1; Odds Ratio [OR] 1.64, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.02-2.66) or emergent care (CTAS 2; OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.41-2.88) were associated with an increased risk of violence, while ‘urgent’ (CTAS 3) or ‘less urgent’ (CTAS 4) acuity levels were not; this variable was reclassified into a ‘High Acuity’ (CTAS 1 or 2) variable.

Parameters for age brackets were constructed using Statistics Canada Life Cycle Groupings, with seniors (aged 65+) as the reference category. All levels were significantly associated with the risk of violence, with elevated risks among youth and working aged patients. These variables were entered into an omnibus main effects multivariable model (analysis step 3) for filtering (

Table 1).

While patient sex was not significantly associated with the risk of violence on its own, when stratified by life cycle grouping, an effect emerged suggesting that 9-1-1 calls involving young and working aged men were associated with an increased risk of violence (

Table 2). These parameters were reclassified into a 3-level composite patient demographic variable for inclusion in adjusted models.

Adjusted Models

After entering the variables as described above into an omnibus main effects model, dispatch priority (urgent: OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.80-1.06), as well as some levels of the location variable (store: OR 1.32, 95% CI 0.92-1.88; and long-term care home: OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.90-1.96) and primary problem variable (chest pain: OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.85-1.72) were no longer significant at the p<0.05 threshold. These covariates were dropped.

Introducing an interaction term for call location by primary presenting problem yielded no covariates significant at p<0.05 and resulted in some levels of the location code losing significance in the more complicated model. The same was true for introducing a term for shift by call location; in both cases, the terms were dropped. However, introducing a term for high acuity by primary presenting problem indicated that patients with a CTAS score of 1 or 2 with a primary presenting problem related to mental health (‘behavioral/psychiatric problem’ per the ACR code) were associated with an increased risk of violence (OR 3.54, 95% CI 2.47-5.08). Importantly, the directionality of this effect is questionable, given that triage guidelines score violent patients with mental health concerns higher. The term was not significant for other variable levels. The final model is presented in

Table 3.

Secondary Outcome: Any Assault

We repeated this process for our secondary outcome of any physical or sexual assault, beginning first with the covariates identified during our univariate analyses as associated with an increased risk of any violence (

Table 1 and

Table 2) entered into an omnibus main effects model, call location (long-term care home), primary problem code (intoxication, mental health, trauma/injury, and altered mental status), and high acuity (as described above) were significantly associated with an increased risk of an assault on a paramedic, while younger age strata were associated with lower risks. Because of the smaller number of events, we did not test for interaction effects between covariates in our secondary outcome analysis. The details of variables included in the final model are presented in

Table 4.

Discussion

Our objective in this study was to identify characteristics of 9-1-1 calls that are associated with an increased risk of violence and, more specifically, with an increased risk of physical or sexual assault on a paramedic. We found that calls occurring in public locations (e.g., hotel, street, restaurant/bar), during afternoon or overnight shifts, or involving young or working age males presented an increased risk of all forms of violence. The risk, however, appeared to be largely driven by the primary presenting problem, particularly for problem codes related to substance use - such as alcohol or drug (including opioid) intoxication - and mental health-related concerns. In our adjusted models, the odds ratios for these two broad areas of concern were large, particularly for our secondary outcome of any assault. These findings have important implications for research and policy.

First, and from a research perspective, the rates of violence we observed are lower than have been found in a recent study involving 15 Emergency Medical Services (EMS) agencies in the Midwest United States [

9]. Using a checkbox reporting process embedded in the ePCR, McGuire and colleagues recorded 8.6 violent encounters per 1,000 9-1-1 calls and 3.7 assaults per 1,000 9-1-1 calls [

9] - rates approximately double those in our study. One plausible explanation for the difference is the administrative burden associated with the respective reporting processes. In our study, the paramedics completed a full incident report with several drop-down menu selection questions, in addition to free text fields. The ePCR software prompts the paramedics to complete the report if they experienced violence during the call but the report itself is not mandatory. In McGuire’s study, however, the reporting process involved a single mandatory question on the ePCR [

9]. Given pervasive underreporting [

7,

9,

23], reducing the administrative burden to document violent encounters appears to be important. Merging the two approaches such that every ePCR has a mandatory filtering question about violence could be useful, with affirmative responses then generating a more detailed - but streamlined - incident report.

Second, like our study, McGuire’s recent work also pointed to 9-1-1 calls involving male patients, alcohol or drug use, and emotional distress, behavioral, or psychological problems as presenting an increased risk of violence [

9]. Similarly, a recent study by Kim and colleagues of two US EMS agencies demonstrated that violent 9-1-1 calls were most commonly associated with psychiatric-related presenting problems [

32]. In our data, calls where the primary presenting problem was related to mental health or substance use concerns accounted for approximately 7% of the overall call volume but were listed as the primary problem in 60% of documented assaults. Meanwhile, sudden cardiac arrest - around which most modern paramedic services are optimized - accounted for less than 1% of calls during the study period. This underscores a well-documented imbalance between paramedic service delivery and community need [

33,

34] but suggests the misalignment problem may be contributing to an elevated risk of occupational violence.

Recent qualitative research has begun to shed light on the potential safety implications - for both providers and patients - of this misalignment problem. For example, Drew and colleagues identified that resource, legislative, and training constraints mean Australian paramedics are often ill-prepared to respond to calls involving mental health problems, creating tension at the scene that can escalate into violence [

35]. Similarly, work by Ford-Jones and Bolster underscored that entry-to-practice training, practice guidelines, and policy documents often prime paramedics to expect violent behavior from patients accessing 9-1-1 for mental health or substance use concerns [36-38]. Combined with a lack of suitable treatment and disposition pathways and specialist clinicians, the result, again, is that paramedics lack the ability to safely engage with patients with mental health concerns, creating an increased risk for violence against the paramedics and sub-optimal care for patients [

38]. Finally, a recent scoping review by Bolster and colleagues on the evolving paramedic role in the opioid crisis underscored the need for paramedic services to provide culturally competent, holistic patient care for people who use drugs [

36].

Taken together, the extant research suggests that (1) 9-1-1 calls involving mental health and substance use are highly prevalent [

36,

38,

39]; (2) gaps in paramedic training, clinical practice guidelines, and regulatory frameworks mean paramedics are both individually and organizationally ill-prepared to respond to these call types [

35,

37,

38]; and (3) the resulting misalignment in service delivery poses legitimate safety risks to paramedics [

9,

32], in addition to contributing to poor outcomes for patients [

38]. One promising solution is the development of specialized interdisciplinary teams tasked specifically with responding to mental health and substance use crises in the community. Although within the context of 9-1-1 response these teams are commonly deployed using police infrastructure, there is early work on new frameworks for such teams to develop within Ontario paramedic services [

40]. Similarly, a recent study examined the impact of a new alternative treatment and disposition pathways for paramedics for patients with mental health concerns [

39]. In the initial evaluation, as many as 1 in 3 patients with mental health concerns were eligible to be transported to a specialized mental health crisis centre, resulting in a 50% reduction in ambulance offload delay times, with 96% of paramedics rating the program favorably [

39].

While these programs can reasonably be expected to improve service delivery for patients accessing paramedic services for mental health-related concerns and may mitigate at least some of the violence risk associated with these encounters, occupational violence against paramedics is a complex problem, requiring a multimodal response. Recent studies have proposed body armour for paramedics [

10], body-worn and in-vehicle cameras [

41], address hazard flagging [

42], and high-fidelity simulation training [

43] as potential solutions, albeit with mixed results. Ultimately, the research in this area is still developing and additional studies are needed. One promising intervention is a new 3-question violence risk assessment tool developed specifically for use by paramedics. In its derivation phase, the Aggressive Behavior Risk Assessment Tool for Emergency Medical Services (ABRAT-EMS) had a positive predictive value of 34% for identifying potentially violent EMS patients and a negative predictive value of 99% for patients below the “high” risk threshold [

32]. This suggests the checklist has potential as a short, point-of-contact violence screening tool. Replicating these findings in other services and adapting these or similar tools for upstream risk assessment during 9-1-1 call-taking is an important avenue for further research.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted within the context of certain limitations. First, as with any retrospective study, the validity of our findings hinges on the quality of the documentation, which can be inconsistent across providers. Second, and on a related note, earlier research has highlighted that occupational violence in healthcare is chronically underreported [

44]. This not only means our estimates might be conservative, but also introduces the potential for selection bias in the events that the paramedics feel warrant documenting - potentially inflating the relative risks associated with certain call types. Third, the covariates used in our modelling are not always available to the paramedic at the point of call assignment. Ideally, the analysis would have leveraged dispatch triaging tools that classify 9-1-1 calls into predetermined categories; however, the call prioritization software changed midway during our study. Future research should examine whether certain dispatch classifications are associated with an increased risk of violence. This would allow for easier and earlier risk mitigation before crews are dispatched to potentially violent scenes. Finally, we made no effort to validate the veracity of the paramedics’ claims of violence documented in the reports, although we have no reason to doubt them.

Conclusion

Out of every 1,000 9-1-1 calls, more than four resulted in a documented incident of violence against the responding paramedics. Calls occurring during afternoon or overnight hours, at non-residential locations, involving young or working-aged men, and for problems of altered mental status and - especially - mental health or substance use were associated with an increased risk of violence, particularly physical assault. In concert with related research, our findings point to an urgent need for paramedic services to consider new approaches to responding to mental health-related calls, in addition to broader violence risk identification and mitigation strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: The External Violence Incident Report; Table S1: Step-by-step accounting of variable reclassification and analysis procedures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.; Methodology, J.M. and E.A.D.; Software, M.J..; Validation, J.M.; Formal Analysis, J.M..; Investigation, J.M., A.B., and E.A.D.; Resources, M.J..; Data Curation, J.M.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, J.M..; Writing – Review & Editing, J.M., M.J., A.B., and E.A.D.; Visualization, N/A.; Supervision, N/A.; Project Administration, M.J.; Funding Acquisition, J.M., M.J., and E.A.D.”

Funding

This study was principally funded by the Region of Peel, Department of Health Services, Division of Paramedic Services. Additional grant funding came from the University of Windsor.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (protocol number 44162, May 3, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in this study using a passive consent mechanism embedded in the External Violence Incident Report wherein paramedics who do not want a specific EVIR used for research purposes could check a box. This opt-out consent strategy was approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board as satisfying the requirement for informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study may be made available to interested researchers on a case-by-case basis, subject to institutional review board approval and a negotiated data sharing agreement with suitable privacy and data security protections.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to paramedics of the Region of Peel for documenting their experiences with workplace violence in support of this research. We also wish to express our gratitude and appreciation to the following individuals for their support and assistance during this study: Michelle Chen and Claudia Mititelu of the Region of Peel’s Strategic Policy and Performance division and Peter Dundas, Brian Gibson, Tom Kukolic, Daniel Mia, Faith Bisram, Jennifer Chadder, Rene Nand, and Cory Tkatch who, at various points in time during the study, were/are members of the executive paramedic leadership team.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors J.M. and M.J., are employed by the Region of Peel.

References

- Maguire, B.J.; O’Meara, P.; O’Neill, B.J.; Brightwell, R. Violence against emergency medical services personnel: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Ind Med 2018, 61, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, B.J.; O’Neill, B.J. Emergency Medical Service Personnel’s Risk From Violence While Serving the Community. Am J Public Health 2017, 107, 1770–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.M.; Davis, A.L.; Shepler, L.J.; Moore-Merrell, L.; Troup, W.J.; Allen, J.A.; Taylor, J.A. A Systematic Review of Workplace Violence Against Emergency Medical Services Responders. New Solut 2020, 29, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, B.J.; Browne, M.; O’Neill, B.J.; Dealy, M.T.; Clare, D.; O’Meara, P. International Survey of Violence Against EMS Personnel: Physical Violence Report. Prehospital and disaster medicine 2018, 33, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olschowka, N.; Möckel, L. Aggression and violence against paramedics and the impact on mental health: A survey study. Journal of Emergency Medicine, Trauma and Acute Care 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Murray, R.; Binzer, M.; Robert Borse, C.; Davis, A.; Gallogly, V.; Ghanbari, R.; Diane McKinsey, L.; Chief David Picone, B.; Gary Wingrove, P. EMERG-ing data: Multi-city surveillance of workplace violence against EMS responders. Journal of Safety Research 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bigham, B.; Jensen, J.L.; Tavares, W.; Drennan, I.; Saleem, H.; Dainty, K.N.; Munro, G. Paramedic self-reported exposure to violence in the emergency medical services (EMS) workplace: A mixed-methods cross sectional survey. Prehospital Emergency Care 2014, 18, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mausz, J.; Johnston, M.; Arseneau-Bruneau, D.; Batt, A.M.; Donnelly, E.A. Prevalence and Characteristics of Violence against Paramedics in a Single Canadian Site. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, S.S.; Bellolio, F.; Buck, B.J.; Liedl, C.P.; Stuhr, D.D.; Mullan, A.F.; Buffum, M.R.; Clements, C.M. Workplace Violence Against Emergency Medical Services (EMS): A Prospective 12-Month Cohort Study Evaluating Prevalence and Risk Factors Within a Large, Multistate EMS Agency. Prehospital Emergency Care 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, S.S.; Bellolio, F.; Sztajnkrycer, M.D.; Sveen, M.J.; Liedl, C.P.; Mullan, A.F.; Clements, C.M. Use of Body Armor by EMS Clinicians, Workplace Violence, and Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Care. JAMA Netw Open 2025, 8, e2456528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schosler, B.; Bang, F.S.; Mikkelsen, S. The extent of physical and psychological workplace violence experienced by prehospital personnel in Denmark: a survey. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2024, 32, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, B.J.; Al Amiry, A.; O’Neill, B.J. Occupational Injuries and Illnesses among Paramedicine Clinicians: Analyses of US Department of Labor Data (2010 - 2020). Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 2023, 38, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, S.S.; Lampman, M.A.; Smith, O.A.; Clements, C.M. Impact of Workplace Violence Against Emergency Medical Services (EMS). Prehospital Emergency Care 2025, 29, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setlack, J.; Brais, N.; Keough, M.; Johnson, E.A. Workplace violence and psychopathology in paramedics and firefighters: Mediated by posttraumatic cognitions. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science 2021, 53, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viking, M.; Hugelius, K.; Kurland, L. Experiences of exposure to workplace violence among ambulance personnel. International Emergency Nursing 2022, 65, 101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Duranceau, S.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; MacPhee, R.; Groll, D.; et al. Mental disorder symptoms among public safety personnel in Canada. Can J Psychiatry 2018, 63, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, M.; Abrahams, R.; Thyer, L.; Simpson, P. Review article: Prevalence of burnout in paramedics: A systematic review of prevalence studies. Emergency medicine Australasia 2020, 32, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, R.P.; Bower, J.K.; Cash, R.E.; Panchal, A.R.; Rodriguez, S.A.; Olivo-Marston, S.E. Association of Burnout with Workforce-Reducing Factors among EMS Professionals. Prehospital Emergency Care 2018, 22, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; El-Gabalawy, R.; Sareen, J.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Anxiety-related psychopathology and chronic pain comorbidity among public safety personnel. J Anxiety Disord 2018, 55, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, E.; Wagner, S.L.; Schmidt, G.; Harder, H. Emergency Response Services Suicide: A Crisis in Canada?

. Journal of Loss and Trauma 2017, 22, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Eddelbuettel, J.C.P.; Eisenberg, M.D. Job Flows Into and Out of Health Care Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Health Forum 2024, 5, e234964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, Y.R.; Lin, Y.P.; Griffiths, P.; Yong, K.K.; Seah, B.; Liaw, S.Y. A global overview of healthcare workers’ turnover intention amid COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with future directions. Hum Resour Health 2022, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mausz, J.; Johnston, M.; Donnelly, E.A. The role of organizational culture in normalizing paramedic exposure to violence. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 2021, 14, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, M.; McKenna, L. Paramedic student exposure to workplace violence during clinical placements - A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Pract 2017, 22, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, D.; Reifferscheid, F.; Kerner, T.; Dressler, J.L.; Stuhr, M.; Wenderoth, S.; Petrowski, K. Association between the experience of violence and burnout among paramedics. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2021, 94, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, M.A.; Crowe, R.P.; Bentley, M.A.; Levine, R. A National Description of Violence toward Emergency Medical Services Personnel. Prehospital Emergency Care 2016, 20, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, B.J.; Hunting, K.L.; Smith, G.S.; Levick, N.R. Occupational fatalities in emergency medical services: a hidden crisis. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2002, 40, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, B.J.; Smith, S. Injuries and fatalities among emergency medical technicians and paramedics in the United States. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 2013, 28, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mausz, J.; Donnelly, E.A. Violence Against Paramedics: Protocol for Evaluating 2 Years of Reports Through a Novel, Point-of-Event Reporting Process. JMIR Res Protoc 2023, 12, e37636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mausz, J.; Johnston, M.; Donnelly, E. Development of a reporting process for violence against paramedics. Canadian Paramedicine 2021, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Park, E.; Nagarajan, M.; Grafstein, E. Patient prioritization in emergency department triage systems: An empirical study of Canadian triage and acuity scale (CTAS). Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 2017, 24, 713–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Dunn, K.; Youells, C.; Whitmore, G.; McComack, A.; Dievendorf, E.; Bell, C.; Burnett, S.J.; Kim, S.; Clemency, B. Aggressive Behavior Risk Assessment Tool for Emergency Medical Services. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2025, 6, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strum, R.P.; Tavares, W.; Worster, A.; Griffith, L.E.; Costa, A.P. Identifying patient characteristics associated with potentially redirectable paramedic transported emergency department visits in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e054625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, W.; Kaas-Mason, S.; Spearen, C.; Kedzierski, N.; Watts, J.; Moran, P.; Leyenaar, M.S. Redesigning paramedicine systems in Canada with “IMPACC”. Paramedicine 2024. [CrossRef]

- Drew, P.; Devenish, S.; Tippett, V. Paramedic occupational violence: A qualitative examination of aggressive behaviour during out-of-hospital care. Paramedicine 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolster, J.; Armour, R.; O’Toole, M.; Lysko, M.; Batt, A.M. The paramedic role in caring for people who use illicit and controlled drugs: A scoping review. Paramedicine 2023, 20, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolster, J.L.; Batt, A.M. An Analysis of Drug Use-Related Curriculum Documents for Paramedic Students in British Columbia. Cureus 2023, 15, e48515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford-Jones, P.C. Enhancing Safety and Mitigating Violence on Prehospital Mental Health Calls: For the Care Providers and Care Recipients. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health 2023, 42, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, P.; Ford-Jones, P.; Carter, D.; Duhaney, P.; Adam, S.; Pomeroy, D.; Thompson, S. Examining an Alternate Care Pathway for Mental Health and Addiction Prehospital Emergencies in Ontario, Canada: A Critical Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford-Jones, P.; Thompson, S.; Pomeroy, D.; Duhaney, P.; Adam, S.; Gebremikael, L.; Carter, D.; Iheanacho, C.; Meijer, P. An Integrated Crisis Care Framework: A Community-Informed Approach; Humber Polytechnic: Ontario, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bruton, L.; Johnson, H.; MacKey, L.; Farok, A.; Thyer, L.; Simpson, P.M. The impact of body-worn cameras on the incidence of occupational violence towards paramedics: a systematic review. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 2022, 14, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mausz, J.; Piquette, D.; Bradford, R.; Johnston, M.; Batt, A.M.; Donnelly, E. Hazard flagging as a risk mitigation strategy for violence against emergency medical services. Healthcare 2024, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.G., Jr.; DeLuca, M.B.; Crowe, R.P.; Cash, R.E.; Rivard, M.K.; Williams, J.G.; Panchal, A.R.; Cabanas, J.G. Emergency medical services professional behaviors with violent encounters: A prospective study using standardized simulated scenarios. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2022, 3, e12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirico, F.; Afolabi, A.A.; Ilesanmi, O.S.; Nucera, G.; Ferrari, G.; Szarpak, L.; Yildirim, M.; Magnavita, N. Workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Health and Social Sciences 2022, 7, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).