Since the dramatic therapeutic effects of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors with activating alterations of the

EGFR gene were first reported in 2004 [

1], numerous driver gene variants have been identified as therapeutic targets in non-small cell lung cancer, particularly in adenocarcinoma [

2,

3,

4]. In lung adenocarcinoma, driver gene variants occur mutually exclusively [

5]. According to National Cancer Center (NCC) Japan, most mutations in this country involve

EGFR and

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene (KRAS), whereas other mutations are less common [

5]. In clinical practice for lung cancer, the routine search for driver gene mutations has become standard with tests such as the Amoy Dx

® lung cancer multi-gene PCR panel and Oncomine Dx Target Test.

However, routine pathological examination based primarily on hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining has not typically led to identifying driver gene mutations, with some exceptions, such as

ALK fusion lung cancer [

2,

6]

We report a case of lung adenocarcinoma in which MET exon 14 skipping and KRAS mutations were suggested as potential driver gene mutations based on HE staining, thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1; clone: 8G7G3/1) immunohistochemical staining, and other clinical pathological findings.

During a routine health check, a 76-year-old nonsmoking Japanese woman was identified as having an abnormal shadow in her chest. CEA was elevated at 7.6 ng/mL. A subsequent computed tomography scan revealed a nodular lesion in segment 3 of the right upper lobe (

Figure 1). A bronchoscopy conducted at our respiratory medicine department confirmed a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma. Further evaluation classified the cancer as cT1cN0M0, cStage IA3 (TNM, UICC 8th edition), leading to performance of a right upper lobectomy. Macroscopically, the right upper lobectomy specimen weighing 110 g was submitted for pathologic examination (

Figure 2). The tumor appeared lobulated with a solid milky white appearance, accompanied by areas of carbon deposition, and measured 19 × 15 × 10 mm. Notably, it exhibited features of pleural invasion. Microscopically, the tumor displayed a proliferation pattern consistent with adenocarcinoma, comprising 50% acinar pattern, 30% papillary pattern, and 20% lepidic pattern (

Figure 3a, b). Invasion of the pleura was observed, and the tumor was spread through the surrounding air spaces (

Figure 3c). An intrapulmonary micrometastasis was also identified near the primary lesion. Numerous hyaline globules (HGs) termed thanatosomes were noted with some containing nuclear dust (

Figure 3d). Nuclear pleomorphism was prominent (

Figure 3e), and some tumor cells showed scattered cytoplasmic clearing (

Figure 3f). HGs revealed periodic acid-Schiff reactivity with diastase resistance and fuchsinophilia in Masson’s trichrome stain (

Figure 4a, b). HGs were also strongly stained blue-black with Mallory’s PTAH stain (

Figure 4c). Immunohistochemically, the HGs were positive for cleaved caspase-3 (

Figure 5a). The adenocarcinoma cells were heterogeneously positive for TTF1 (clone: 8G7G3/1) (

Figure 3f, inset). There was no metastatic disease in the lymph nodes. The pathological staging was pT3N0M0; pStage IIB (TNM, UICC 8th edition). The patient’s postoperative course has been satisfactory. We ordered the Amoy Dx

® lung cancer multi-gene PCR panel for further analysis. Genetic testing revealed a positive result for

KRAS G12D/S and a negative result for

MET exon 14 skipping.

KRAS is a G protein associated with the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway. Gene alteration in the

KRAS gene (chromosome 12p12.1) leads to a constitutively activated GTP-bound state, which is thought to drive the proliferation of cancer cells [

7]. It is known that the frequency of driver gene mutations in lung adenocarcinoma differs between the USA and Japan. According to NCC Japan, the frequency of

KRAS mutations was 9.7% among 319 Japanese cases of lung adenocarcinoma, making it the second most common driver gene mutation after

EGFR [

5].

KRAS mutations are observed in various types of adenocarcinomas, including HNF4α-positive mucinous adenocarcinoma, TTF1-positive terminal respiratory unit type adenocarcinoma, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition type non-terminal respiratory unit type adenocarcinoma [

8,

9]. The

KRAS G12C mutation is associated with poor prognosis in pulmonary adenocarcinoma of stages I to III [

10]. It is the most common

KRAS mutation in 13–16% of pulmonary adenocarcinoma cases in Western populations [

10,

11]. In contrast, among Asian populations, it is observed in approximately 4% of lung cancer cases, with a higher frequency specifically in pulmonary adenocarcinoma, and is correlated with smoking [

12]. Recently, sotorasib (AMG 510) has been reported to induce tumor shrinkage in patients with lung cancer harboring

KRAS G12C mutations [

10,

13]. In our case, detailed investigations concluded that the lung adenocarcinoma was due to a

KRAS gene alteration.

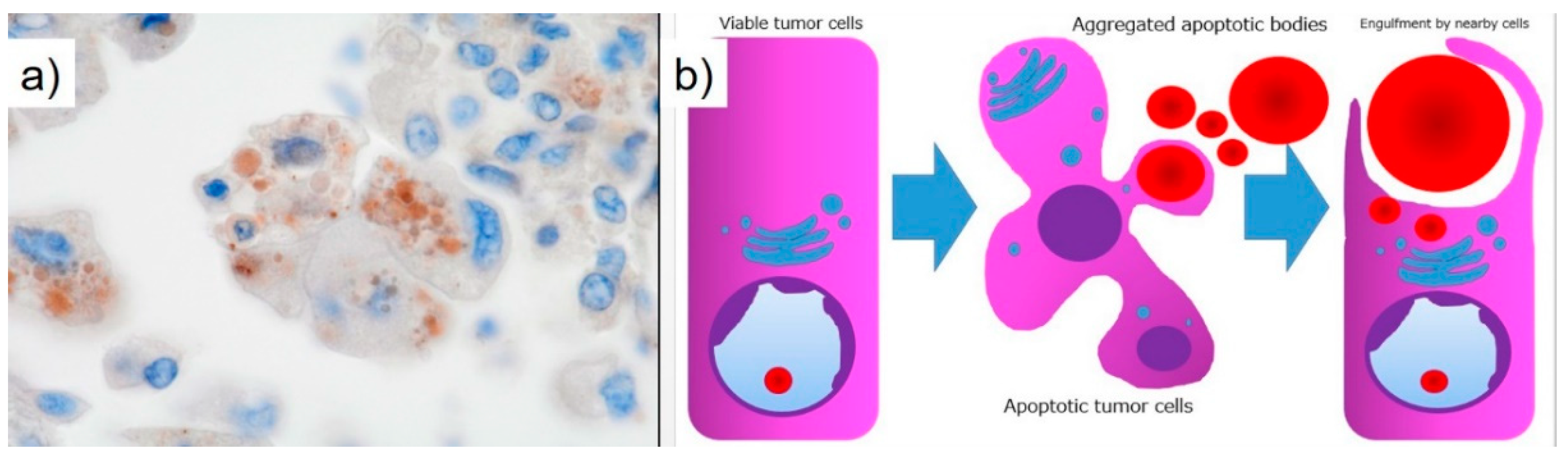

Thanatosomes, first proposed in 2000, were initially categorized as apoptosis-associated bodies (

Figure 5b) [

14] and can be associated with both tumor and non-tumor lesions. We reported instances in which not all thanatosomes were apoptosis-related bodies [

15]. Thanatosomes reveal periodic acid-Schiff reactivity with diastase resistance, fuchsinophilia with Masson’s trichrome stain, and dark blue-black color with Mallory’s PTAH stain, as shown in

Figure 4 [

14,

15].

Hayashi et al. reported that thanatosomes (HGs) were shown in 10.7%, nuclear pleomorphism in 13.1%, and clear cell features in 8.2% of

KRAS-mutant pulmonary adenocarcinomas [

16]. Thanatosomes, nuclear pleomorphism, and clear cell features were also observed in the present case (

Figure 3). Hayashi et al. stated that thanatosomes associated with lung cancer are indeed apoptosis-related bodies [

16]. We utilizing cleaved caspase-3 as an immunohistochemical marker for apoptosis also showed that thanatosomes are clearly apoptosis-associated bodies (

Figure 5a) [

15]. Cleaved caspase-3, an activated caspase-3, is an excellent and reproducible immunohistochemical marker for apoptosis. The biochemical pathways of apoptosis are controlled by caspases (cysteine aspartate-specific proteases), which cleave and activate various intracellular proteins. Cleaved caspase-3 functions as a kind of control tower for apoptosis: it cleaves poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, cytokeratin 18, vimentin, actin, and other intracytoplasmic proteins. Cleaved caspase-3 has been applied to detect apoptotic neoplastic cells in paraffin sections [

14]. Histological findings in the present case revealed the presence of nuclear dust within some of the thanatosomes (

Figure 3d), supporting this conclusion.

To our knowledge, the present case report is the first in which one notable morphological feature is the presence of thanatosomes in

KRAS-mutant pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Building on the findings of Hayashi et al. [

16], we propose that the three pathological findings of thanatosomes, nuclear pleomorphism, and cytoplasmic clearing are associated with

MET exon 14 skipping and

KRAS gene alterations in most but not all cases [

16]. Pathologists observing these three histological features in lung adenocarcinoma specimens may consider conveying this information to clinicians, given the high prevalence of

KRAS mutations in such cases.

Research on medical applications of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has advanced significantly in recent years. It is anticipated that standard implementations of AI in pathology will not be far off. Multiple studies have shown that using convolutional neural networks makes it possible to predict the presence of various driver gene mutations solely from HE-stained images [

17,

18]. By continuing to compare HE-stained specimen images with driver gene mutations, as illustrated in this case report, we can incorporate these insights into AI systems. This could improve the accuracy in detecting driver gene mutations from HE-stained images, potentially shortening the turnaround time from specimen collection to the reporting of genetic test results to patients.

This study has one major limitation: it is a single case report from a single institution in Japan. Additional clinicopathological analyses, including multicenter studies, are needed to definitively determine the cause and pathophysiology of this condition. Therefore, reports from other countries, cultures, and hospitals are awaited.

In conclusion, the authors conducted a detailed analysis of tissue diagnosis centered on HE-stained specimens that allowed us to estimate driver gene mutations in this study. Specifically, we identified three histological features as particularly important: HGs, nuclear pleomorphism, and cytoplasmic clearing. HGs are associated with apoptosis and suggest apoptotic activity in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Moving forward, we aim to utilize routine HE-stained tissue images to estimate various driver gene mutations as a contribution to improving the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and T.H.; Validation, M.T.; Investigation, M.T.; Resources, Y.I. and R.F.; Data Curation, M.T. and K.T.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.T.; Writing – Review and Editing, M.U., J.K., and T.H.; Supervision, M.U., J.K., and T.H.; Project Administration, M.T., Y.I., and R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975) and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shimada General Medical Center (protocol code: R6-6; date of approval: November 07, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the subject included in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Naoki Ooishi, Mr. Takayoshi Hirota, Mr. Kuniaki Muramatsu, Mr. Mizuki Naruse, and Ms. Chinatsu Tsuchiya (Division of Pathology and Oral Pathology, Shimada General Medical Center, Shimada, Shizuoka, Japan) for helpful technical support with the immunohistochemical staining; Dr. Hiroto Ishiki (Department of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital, Tsukiji, Chuo-ku, Tokyo, Japan) for valuable advice in preparing for a poster session at the 115th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Pathology in Sapporo in 2026; and Prof. Hiroko Tina Tajima (St. Marianna University School of Medicine, Kawasaki, Kanagawa, Japan) for kindly reviewing and editing the English manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EGFR |

epidermal growth factor receptor |

| KRAS |

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene |

| HG |

hyaline globule |

| TTF |

thyroid transcription factor |

| AI |

artificial intelligence |

| NCC |

National Cancer Center |

References

- Lynch, T.J.; Bell, D.W.; Sordella, R.; Gurubhagaratula, S.; Okimoto, R.A.; Brannigan, B.W.; Harris, P.L.; Haserlat, S.M.; Supko, J.G.; Haluska, F.G.; et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inamura, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Togashi, Y.; Hatano, S.; Ninomiya, H.; Motoi, N.; Mun, M.Y.; Sakao, Y.; Okumura, S.; Nakagawa, K.; et al. EML-ALK lung cancers are characterized by rare other mutations, a TTF-1 lineage, an acinar histology, and young onset. Mod. Pathol. 2009, 22, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, A.; Kohno, T.; Tsuta, K.; Wakai, S.; Arai, Y.; Shimada, Y.; Asamura, H.; Furuta, K.; Shibata, T.; Tsuda, H. ROS1-rearranged lung cancer: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 15 surgical cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 37, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshizawa, A.; Sumiyoshi, S.; Sonobe, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Fujimoto, M.; Kawakami, F.; Tsuruyama, T.; Travis, W.D.; Date, H.; Haga, H. Validation of the IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma classification for prognosis and association with EGFR and KRAS gene mutations: analysis of 440 Japanese patients. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2013, 8, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, M.; Shiraishi, K.; Kunitoh, H.; Takenoshita, S.; Yokota, J.; Kohno, T. Gene aberrations for precision medicine against lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyata-Morita, K.; Morita, S.; Matsutani, N.; Kondo, F.; Soejima, Y.; Sawabe, M. Frequent appearance of club cell (Clara cell)-like cells as a histological marker for ALK-positive lung adenocarcinoma. Pathol. Int. 2019, 69, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haigis, K.M. KRAS alleles: The devil is in the detail. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, K.; Tomizawa, K.; Mitsudomi, T. Biological and clinical significance of KRAS mutations in lung cancer: an oncogenic driver contrasting with EGFR mutation. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010, 29, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, D.; Ishikawa, S.; Oguni, S.; Aburatani, H.; Fukayama, M.; Niki, T. Co-activation of epidermal growth factor receptor and c-MET defines a distinct subset of lung adenocarcinomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 2191–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canon, J.; Rex, K.; Saiki, A.Y.; Mohr, C.; Cooke, K.; Bagal, D.; Gaida, K; Holt, T.; Knutson, C.G.; Koppada, N.; et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2019, 575, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014, 511, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loong, H.H.F.; Du, N.; Cheng, C.; Lin, H.; Guo, J.; Lin, G.; Li, M.; Jiang, T.; Shi, Z.; Cui, Y.; et al. KRAS G12C mutations in Asia: a landscape analysis of 11,951 Chinese tumor samples. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, T.K.H.; Skoulids, F.; Kerr, K.M.; Ahn, M.J.; Kapp, J.R.; Soares, F.A.; Yatabe, Y. KRAS G12C in advanced NSCLC: Prevalence, co-mutations, and testing. Lung Cancer 2023, 184, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadimitriou, J.C.; Drachenberg, C.B.; Brenner, D.S.; Newkirk, C.; Trump, B.F.; Silverberg, S.G. “Thanatosomes”: a unifying morphogenetic concept for tumor hyaline globules related to apoptosis. Hum. Pathol. 2000, 31, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachibana, M.; Koreyasu, R.; Kamimura, K.; Tsutsumi, Y. Pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with hyaline globules (thanatosomes): report of two cases. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2021, 14, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, T.; Kohsaka, S.; Takamochi, K.; Kishikawa, S.; Ikarashi, D.; Sano, K.; Hara, K.; Onagi, H.; Suehara, Y.; Takahashi, F.; et al. Histological characteristics of lung adenocarcinoma with uncommon actionable alterations: special emphasis on MET exon 14 skipping alterations. Histopathology 2021, 78, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Jung, A.W.; Torne, R.V.; Gonzalez, S.; Vöhringer, H.; Shmatko, A.; Yates, L.R.; Jimenez-Linan, M.; Moore, L.; Gerstung, M. Pan-cancer computational histopathology reveals mutations, tumor composition and prognosis Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 800–810. [Google Scholar]

- Kather, J.N.; Heij, L.R.; Grabsch, H.I.; Loeffler, C.; Echle, A.; Muti, H.S.; Krause, J.; Niehues, J.M.; Sommer, K.A.J.; Bankhead, P.; et al. Pan-cancer image-based detection of clinically actionable genetic alterations. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).