Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Phased array antennas provide the ability to electronically steer a beam, eliminating the need for mechanical adjustments [1]. While traditionally used in military applications, there is growing interest in their adoption across various fields [1,2]. Conformal antennas, a type of phased array, are designed for installation on curved or non-flat surfaces, enabling focused radio wave radiation [1,2]. These antennas can be integrated into various applications, including aerospace, wearable technology, vehicles, and modern mobile devices [2], while also reducing traditional antenna height to support the integration and coexistence of multiple radio technologies within a compact area [1,2]. Planar arrays, composed of elements with phase shifters in a matrix, are compact and cost-effective due to mass production via printed circuit technology [1–3]. These antennas, when mounted on rigid surfaces, exhibit robustness, provide beam deflection in two planes, and offer high gain with rapid beam-switching capabilities [1,3]. However, planar antennas can experience interference between feed lines and elements, often supporting narrow bandwidths and exhibiting relatively low radiation efficiency [1,3]. Conformal antennas, which are easily mounted on curved surfaces, are particularly suited for wearable applications, spacesuits, and aerospace designs [1,2,4]. By minimizing connection length, they bring electronics closer to the antenna elements, reducing signal loss while enhancing transmission power and receiver sensitivity, especially at higher frequencies [4]. Research into 3Dprinted conformal antennas has emerged as a significant field of study [1,5]. This paper presents the mathematical analysis of both planar and conformal antennas, covering key parameters such as gain, bandwidth, radiation efficiency, and mutual coupling for planar arrays, as well as the width and length calculations for rectangular microstrip patch antennas used in conformal designs [2,6–8]. Furthermore, the role of additive manufacturing in antenna development is highlighted, emphasizing its ability to produce antennas with complex geometries thereby revolutionizing conformal antenna design [1,9].

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Planar Arrays (2D)

| Parameter | Definition | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Gain (G) | Ratio of radiated power in a given direction to that of an isotropic antenna | Defines antenna efficiency |

| Bandwidth () | Frequency range where the antenna operates efficiently | Determines multi-band capability |

| Radiation Efficiency () | Ratio of radiated power to total input power | Higher efficiency means better performance |

2.1. Mathematical Analysis of Planar Arrays

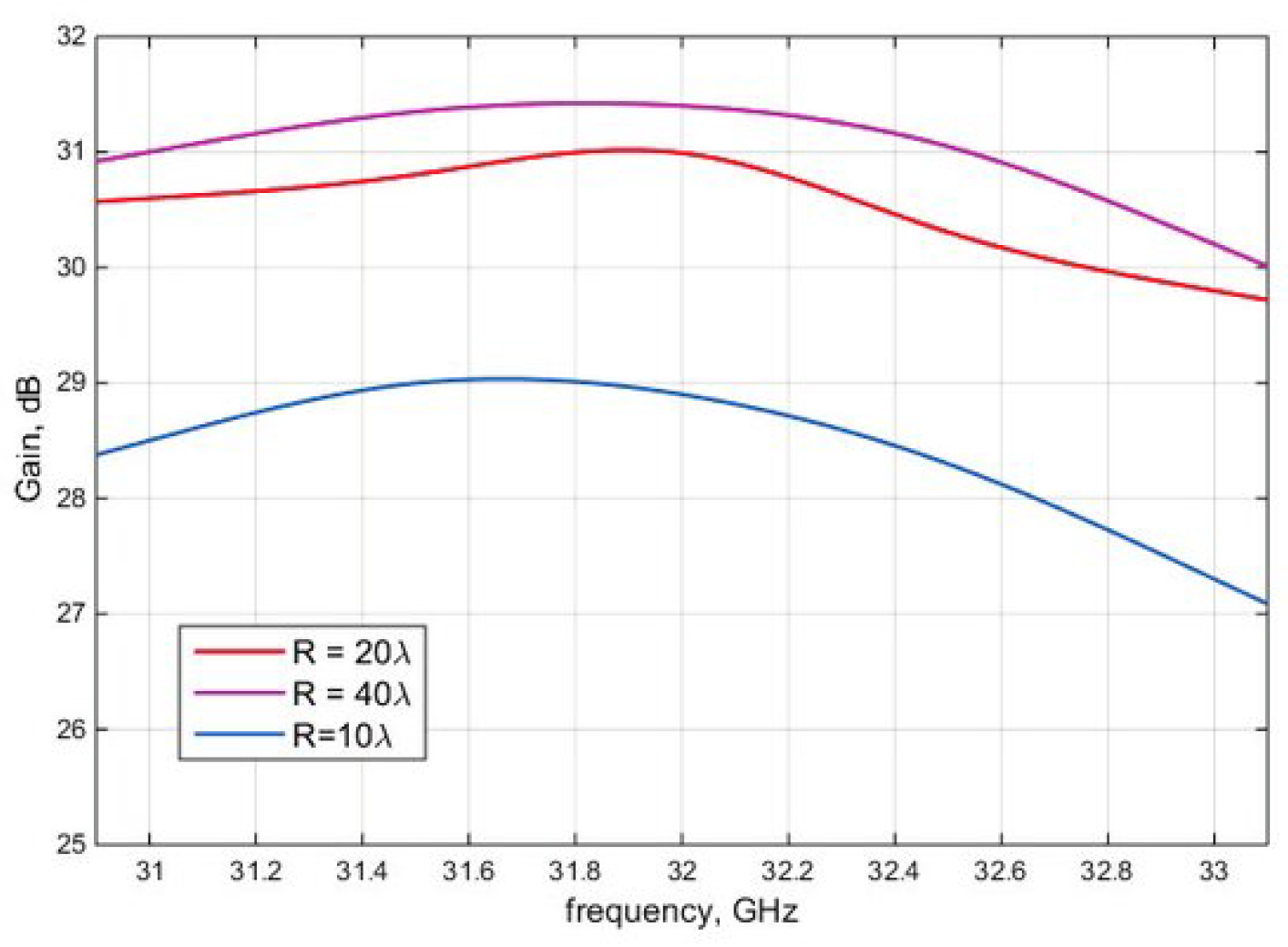

- Antenna Gain (G): The gain of an antenna can be expressed as:where Antenna gain represents the directional amplification of an antenna relative to an isotropic radiator. Higher gain ensures efficient transmission and reception of electromagnetic waves, is the radiated power density in a given direction, and is the radiated power density of an isotropic antenna [2,6].

3. Conformal Arrays (3D)

| Parameter | Planar Antennas | Conformal Antennas |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Flat Surface | Curved Surface |

| Beam Steering | Electronic | Electronic |

| Applications | Wireless, Radar | Aerospace, Vehicles |

| Manufacturing | PCB-based | 3D Printing, Flexible Materials |

3.1. Mathematical Analysis of Conformal Arrays

3.2. Experiment Suggestions for Conformal Antennas

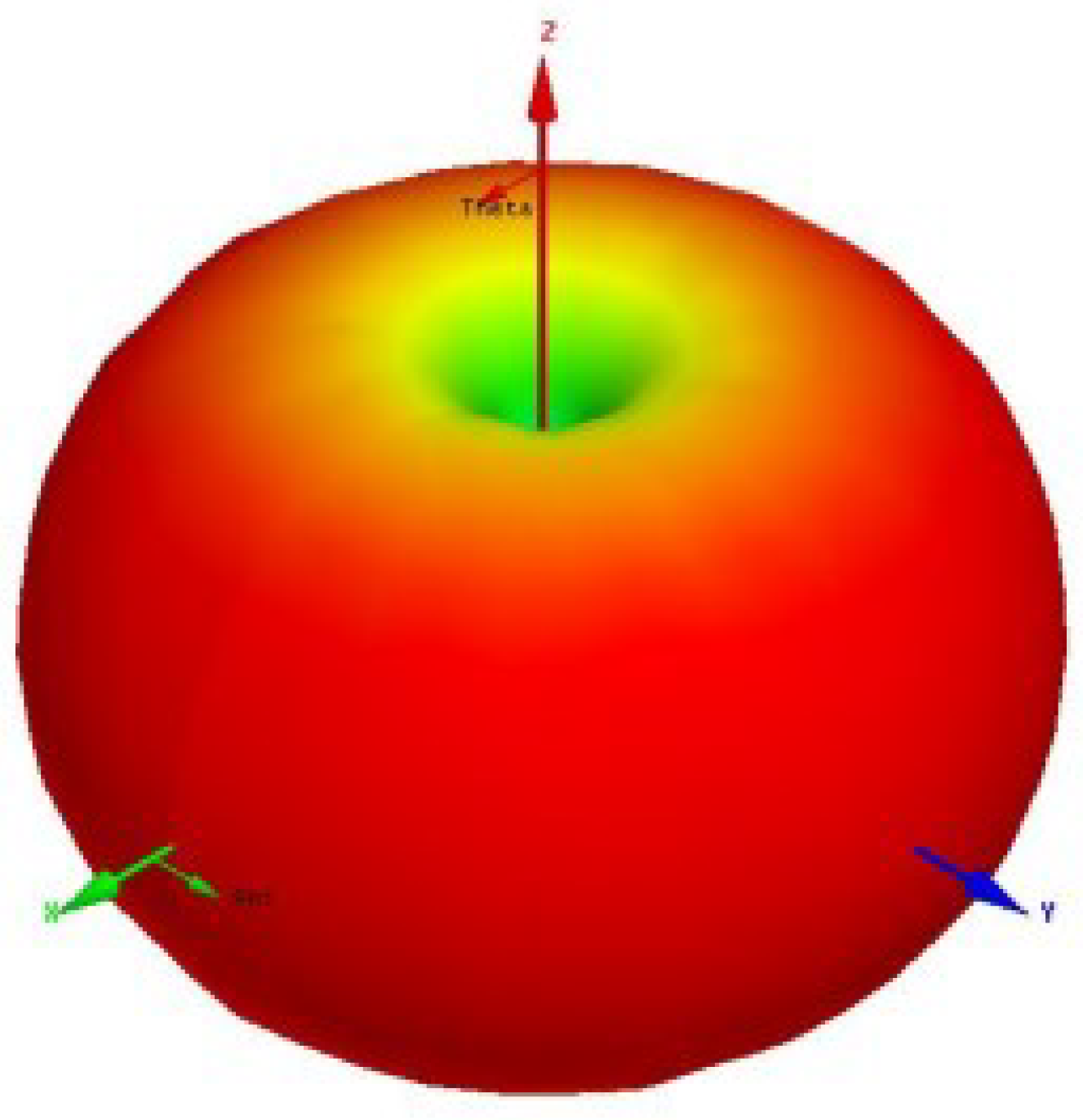

- Radiation Pattern Measurement: The radiation pattern should be measured for different curvature angles () of the conformal antenna. The results should be presented as plots of radiation power as a function of different angles [2,16]. The radiation pattern can be expressed as:where represents the radiated power as a function of azimuth () and elevation () angles [2,16].

4. Automobiles, Planes, and Ships

4.1. Integration in Automotive Applications

4.2. Aerospace and Military Applications

4.3. Mathematical Considerations

-

Radiation Efficiency ():

4.4. Future Trends and Challenges

- Material Science: Continued research in material science is essential to develop lightweight materials with high electromagnetic performance, enabling seamless integration [24].

- Regulatory Standards: As the use of conformal antennas expands, new industry standards and regulations will be necessary to prevent interference with other electronic systems and ensure safety compliance [25].

5. Additive Manufacturing

5.1. The Role of 3D Printing in Antenna Design

- Complex Geometries: 3D printing enables the fabrication of highly complex and intricate antenna structures that would be difficult or prohibitively expensive to produce using traditional methods [1,26]. This capability allows for the optimization of antenna performance for specific applications [1,26].

5.2. Applications of Additive Manufacturing in Antenna Technology

- Phased Array Antennas: 3D printing facilitates the fabrication of phased array antennas with extremely small and closely spaced elements, essential for beam steering and advanced communication systems [28].

- High-Frequency Antennas: The high precision achievable through 3D printing enables the fabrication of antennas operating at high frequencies, such as those used in 5G and satellite communication [28].

- Integrated Antennas: Additive manufacturing allows for the seamless integration of antennas with other electronic components, leading to more compact and efficient systems [29].

5.3. Mathematical Considerations in Additive Manufacturing for Antennas

- Antenna Geometry: The accuracy of 3D printing directly influences antenna geometry, which affects parameters such as resonant frequency, bandwidth, and radiation pattern [30]. Small deviations from the intended dimensions can significantly impact performance [30]. As discussed in Section III, the width and length of microstrip patch antennas must be carefully controlled during the 3D printing process to maintain accurate frequency response [2,30]. Ensuring precise control of these parameters during fabrication is critical for achieving the desired electrical characteristics [2,30].

5.4. Challenges and Future Directions

6. Conclusion

6.1. The Impact of Conformal Antennas

6.2. The Role of 3D Printing in Conformal Antenna Manufacturing

6.3. Future Work

- Material Development: New materials with enhanced electrical, mechanical, and thermal properties are needed for conformal antenna applications [11,39]. Research into materials with high conductivity, low dielectric loss, and good mechanical flexibility is critical to optimizing antenna performance and reliability [11,39].

- Advanced Design Techniques: Continued research is required to develop advanced design methodologies that fully exploit the capabilities of conformal antennas [1,2,40]. This includes the development of new algorithms and simulation tools for accurately predicting the performance of complex antenna structures [1,2,40].

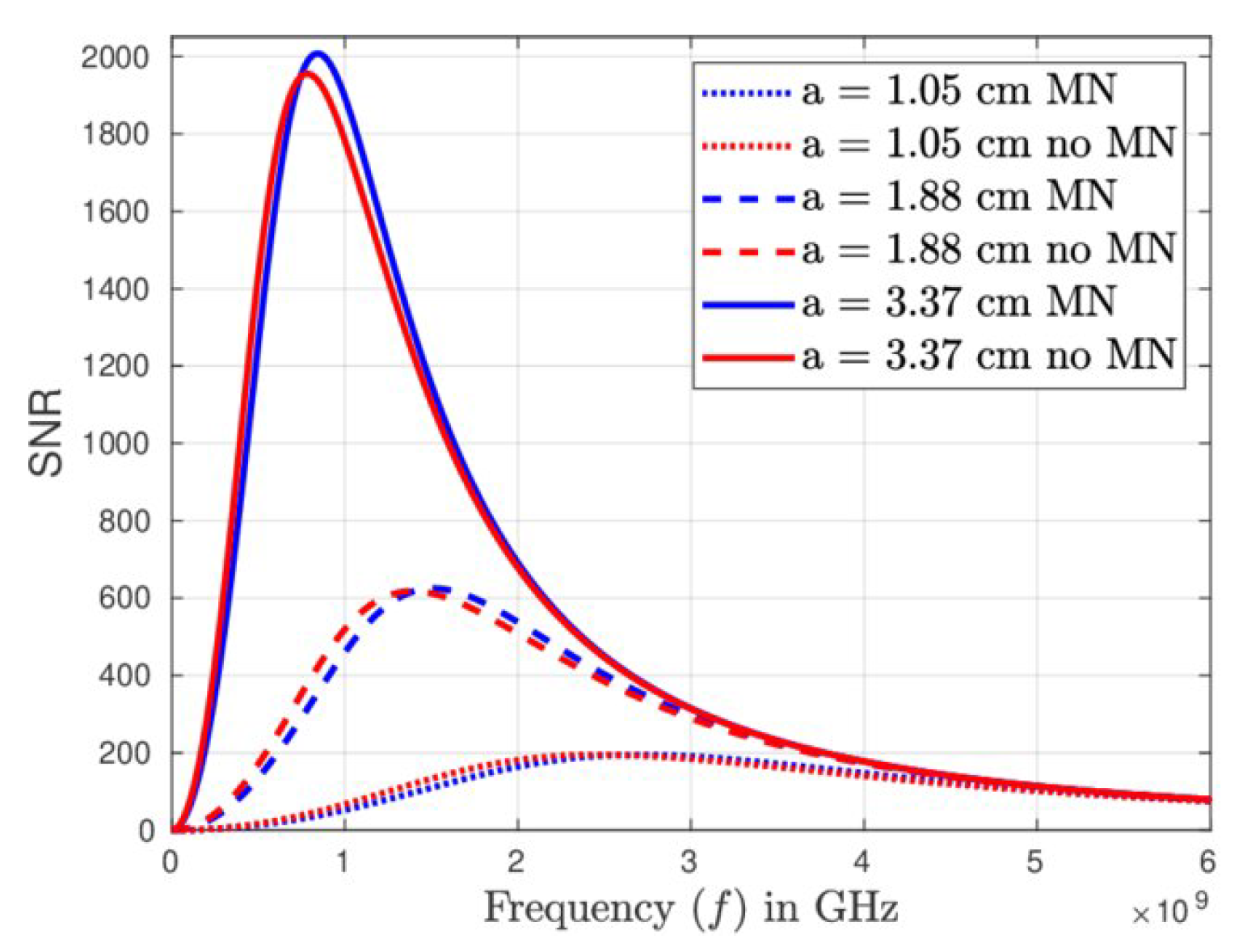

- Experimental Validation: Additional experimental data is needed to verify the performance of conformal antennas under different operating conditions [2,40]. This includes real-world testing to assess reliability and robustness [2,40]. Studies on signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) variations across different frequency bands and operational conditions are necessary [4,40]. Measurements of radiation patterns for different curvature angles will further validate theoretical models [4,40].

- Integration with Other Technologies: Research is required to explore the integration of conformal antennas with other electronic components and systems [7,41]. This includes developing new packaging techniques and integration strategies to minimize interference and optimize overall system performance [7,41].

7. Acknowledgments

8. Additional information

References

- Mailloux, R. Phased Array Antenna Handbook, 3 ed.; Artech House Publishers, 2017.

- Giannakopoulos, G. Design a 1.3 GHz Microstrip Patch Antenna for a PAL TV Signal: A Guidance on How to Design a Microstrip Patch Antenna (2D) Using Ansoft Designer, 1 ed.; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2014.

- G.Giannakopoulos. Multiband Monopole and Microstrip Patch Antennas for GSM and DCS Bands: A Guidance to Design Monopole (2D) and (3D) and Microstrip Patch Antennas by Using Ansoft HFSS, Without Experience!, 1 ed.; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2011.

- Giannakopoulos, G.; Shaikh, K. Design Multiband Monopole and Microstrip Patch Antennas using High Frequency Structure Simulator. arXiv 2024, [2412.06667].

- International, H. Smart Conformal Antenna – A Technical Challenge, 2021. Available online: https://car.harman.com/insights/blog/conformal-antenna (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Salam, A. Design of Subsurface Phased Array Antennas for Digital Agriculture Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Phased Array System & Technology (PAST), 2019, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Aslan, Y.; Puskely, J.; Janssen, J.; Geurts, M.; Roederer, A.; Yarovoy, A. Thermal-Aware Synthesis of 5G Base Station Antenna Arrays: An Overview and a Sparsity-Based Approach. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 58868–58882. [CrossRef]

- Goulding, C. Conformal Antennas and 3D Printing, 2020. Available online: https://www.fabbaloo.com/blog/2020/8/5/conformal-antennas-and-3d-printing (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Bahr, R.; Fang, Y.; Su, W.; Tehrani, B.; Palazzi, V.; Tentzeris, M. Novel Uniquely 3D Printed Intricate Voronoi and Fractal 3D Antennas. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium (IMS), 2017, pp. 1583–1586. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.; Romero, L.; Domínguez, I.; Espinosa, M.; Domínguez, M. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: An Overview about 3D Printing Methods and Future Prospects. Complexity 2019, 2019, 30. [CrossRef]

- Balanis, C.A. Antenna Theory: Analysis and Design; Wiley, 2015.

- Milligan, T.A. Modern Antenna Design; John Wiley & Sons, 2005.

- Ramamoorthy, D. Impact of Mutual Coupling among Antenna Arrays on the Performance of the Multipath Simulator System. Master’s thesis, Department of Electronics, Mathematics and Natural Sciences, 2014.

- Ha, B.; Pirinoli, P.; Beccaria, M.; Orefice, M.; Yang, F. Reflectarray Antennas Printed on Convex Surface. 09 2015. [CrossRef]

- Pozar, D.M. Microstrip Antennas: The Analysis and Design of Microstrip Antennas and Arrays; John Wiley & Sons, 2018 & Sons, 2018.

- Ali, M.; Abd-Alhameed, R. Conformal Array Antenna Theory and Design; John Wiley & Sons, 2018.

- Jain, S.; Singh, V.; Ayub, S. Design of Slotted Microstrip Antenna having high efficiency and gain. 04 2014.

- Hall, P.; Hao, Y.; Parini, C., Eds. Advanced Antenna Systems for 5G and Beyond; John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- Liu, Z.; Li, L.W., Eds. Handbook of Antenna Technologies; Springer, 2021.

- Liu, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y. Beamforming Techniques for Phased Array Antennas. IEEE Communications Magazine 2017, 55, 77–83.

- Kumar, S.; Singh, V. Advances in Phased Array Antenna Design. Progress in Electromagnetics Research 2020, 170, 125–140.

- Kim, H.; Lee, S. A Low-Cost Phased Array Antenna Design for 5G Applications. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters 2019, 18, 2589–2593.

- Gonzalez, D.G.; Smith, D.R. 3D Printed Conformal Antennas. IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine 2017, 59, 22–34.

- Thomas, J.B.; Smith, D.A. Additive Manufacturing of Antennas: A Review. Journal of Materials Science 2018, 53, 12132–12151.

- White, C.; Black, P.; Green, R. 3D Printing of High-Performance Antennas. Advanced Materials Technologies 2020, 5, 1900889.

- Brown, K.; Wilson, L. Material Selection for 3D-Printed Antennas. Additive Manufacturing 2021, 37, 101782.

- Lee, J.H.; Park, K.S. Antenna Parameter Measurement Techniques. Microwave Journal 2016, 59, 22–30.

- Patel, R.; Khan, S.; Nguyen, L. A Comparison of Different Types of Antenna Arrays. IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine 2017, 59, 22–34.

- Johnson, M.; Williams, R. Recent Advances in Antenna Design. Electronics Letters 2018, 54, 744–746.

- Johnson, S.; Williams, T. Conformal Antennas for Automotive Applications: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 9876–9897.

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, B.; Gupta, C. Integration of Conformal Antennas in Aerospace Systems. Aerospace Science and Technology 2019, 95, 105495.

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Antenna Design for IoT and Wearable Applications. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 3475–3490.

- Evans, D.; Jones, S.; Taylor, L. Antenna Systems for Satellite Communication. International Journal of Satellite Communications and Networking 2020, 38, 292–307.

- Fenn, A.J.; et al. The Development of Phased-Array Radar Technology. MIT Lincoln Laboratory Journal 2000, 10, 21–48.

- Dionigi, M.; et al. Millimeter-Wave Phased-Array Antennas. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2008, 56, 529–540. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.; Behera, S.K. A Comprehensive Study on Phased Array Antenna Technologies. Journal of Current Engineering and Technology 2017, 8, 45–58.

- Zang, J.W.; et al. Nonreciprocal Phased-Array Antennas. arXiv preprint 2019, 1911, 1–14.

- Cukierman, A.; et al. Hierarchical Sinuous-Antenna Phased Array for Millimeter Wavelengths. arXiv preprint 2018, 1801, 1–12.

- Kim, J.; et al. Physical Design and Experimental Verification of a Huygens’ Metasurface Two-Lens System for Phased-Array Scan-Angle Enhancement. arXiv preprint 2022, 2211, 1–10.

- Rocca, P.; et al. Modular Design of Hexagonal Phased Arrays Through Diamond Tiles. arXiv preprint 2021, 2102, 1–8.

- Delos, P.; et al. Phased Array Antenna Patterns—Part 1: Linear Array Beam Characteristics and Array Factor. Analog Dialogue 2020, 54, 1–7.

- Ehyaie, D. Novel Approaches to the Design of Phased Array Antennas. PhD thesis, University of Michigan, 2011.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).