3.2. ERP Component Analysis

3.2.1. N1 Component

(1) Average N1 Amplitude

A three-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted on the mean amplitude of the N1 component, with emotional motivational intensity (high vs. low), emotional motivational direction (approach vs. avoidance), and 12 electrode positions (e.g., F3, Fz, F4, etc.) as within-subject factors. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of emotional motivational intensity on N1 amplitude, F(1,59) = 6.643, p < 0.05, η²= 0.231, indicating that this factor plays a crucial role in early perceptual processing and the allocation of attentional resources. Specifically, low emotional motivational intensity elicited a more pronounced (more negative) N1 amplitude compared to high intensity conditions.

In contrast, the main effect of emotional motivational direction on N1 amplitude was not significant, F(1,59) = 4.034, p > 0.05, η²= 0.175, suggesting that early neural responses may be less sensitive to the direction of motivational cues at this stage.

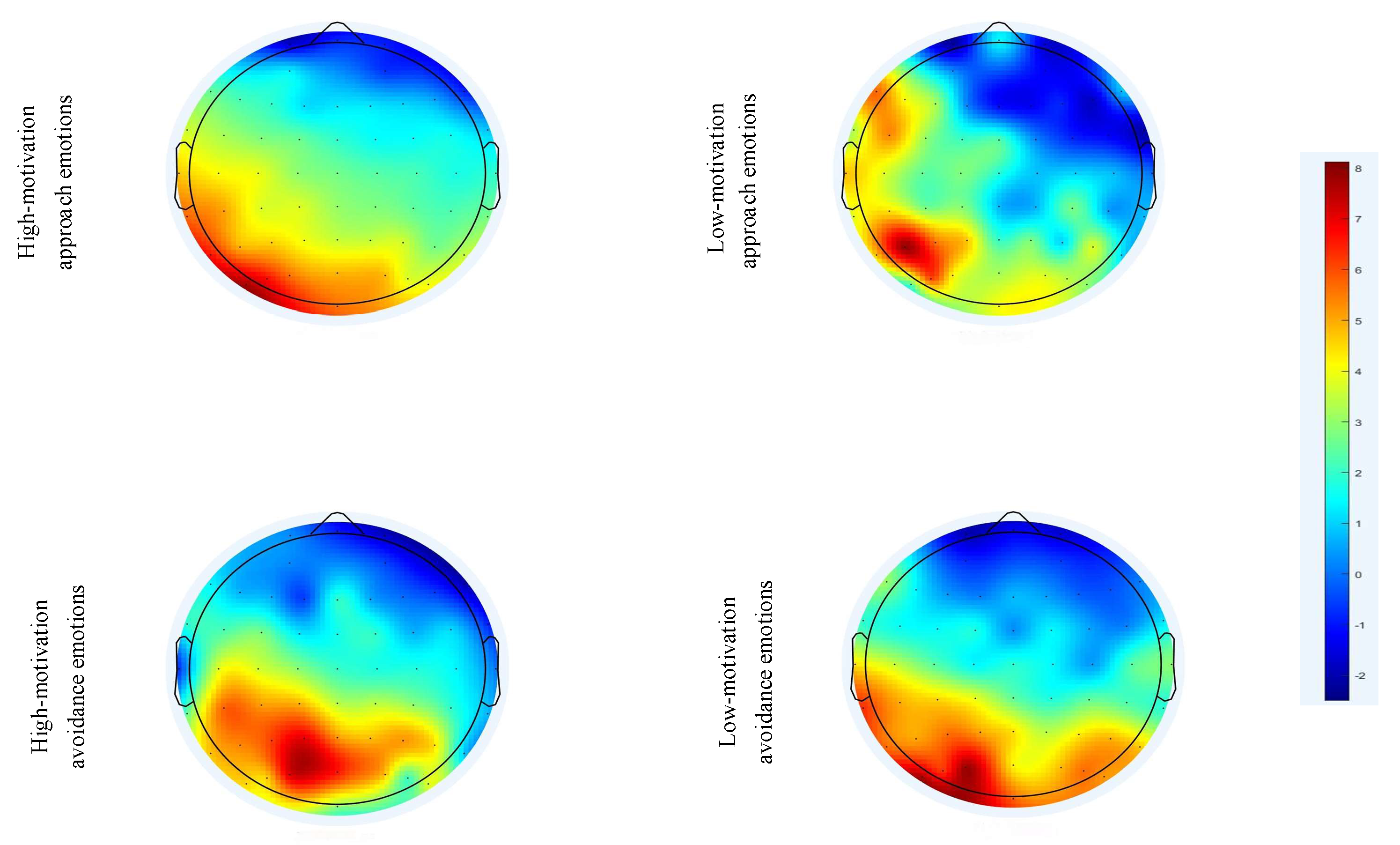

A significant main effect of electrode position was also observed, F(2.849,168.051) = 7.503, p < 0.05, η²= 0.723. Post-hoc tests indicated significant differences in N1 amplitude across various brain regions, with particularly pronounced activation in the right prefrontal area (see

Figure 4). Under high motivational intensity, brain activity was concentrated in the frontal and parietal lobes and exhibited smaller negative amplitudes; under low motivational intensity, the activity was more dispersed, with larger negative amplitudes. Notably, the right frontal electrodes (F4, C4, FC4) showed significant N1 amplitude changes under all conditions.

No significant interactions were found between emotional motivational intensity and direction, electrode position (p > 0.05), nor was the three-way interaction significant (p > 0.05).

In summary, emotional motivational intensity significantly affects the amplitude of the N1 wave, with low intensity eliciting a more negative amplitude—indicative of increased attentional resource allocation. The direction of emotional motivation did not have a significant impact on N1 amplitude, and no significant interaction with electrode position was observed. These findings suggest that, at the early stages of attention, neural responses may not differ substantially based on the motivational direction, warranting further research into the underlying neural response mechanisms across different emotional states.

(2)N1 latency period

A three-way repeated measures ANOVA on N1 latency revealed that both emotional motivational intensity and emotional motivational direction significantly influenced N1 latency. Specifically, the results were F(1,59) = 8.213, p < 0.05, η²= 0.129 for intensity and F(1,59) = 7.431, p < 0.05, η²= 0.117 for direction. These findings indicate that variations in both the intensity and direction of emotional motivation significantly affect N1 latency during the early attention processing stage, reflecting differences in the underlying neural mechanisms.

Furthermore, a significant interaction between emotional motivational intensity and direction was observed, F(1,59) = 18.991, p < 0.05,η²= 0.250. In contrast, the interaction between emotional motivational direction and electrode location (F(5.419,319.663) = 0.639, p > 0.05,η²= 0.027), the interaction between emotional motivational intensity and electrode location (F(5.228,308.094) = 0.552, p > 0.05,η²= 0.022), and the three-way interaction among intensity, direction, and electrode location (F(5.187,305.975) = 0.318, p > 0.05,η²= 0.012) were not significant.

In summary, the significant interaction between emotional motivational intensity and direction on N1 latency underscores the complex effects of emotional motivation on attentional resource allocation and processing. However, no significant differences were observed across electrode locations, and the spatial distribution of the interaction between intensity and direction did not reach significance.

3.2.2. P2 Component

(1) Average P2 Amplitude

A three-way repeated measures ANOVA on the average amplitude of the P2 component revealed that the main effect of emotional motivational direction was not significant (F(1,59) = 2.735, p > 0.05). This finding may be attributed to the fact that the P2 component primarily reflects the allocation of attentional resources rather than being directly influenced by emotional motivational direction.

The main effect of emotional motivational intensity on the P2 amplitude was significant, F(1,59) = 3.821, p < 0.05, with the P2 amplitude being significantly higher under high motivational intensity emotions than under low motivational intensity emotions, indicating that high motivational intensity emotions require more cognitive resources.

The main effect of emotional motivational intensity on the P2 amplitude was statistically significant, F(1,59) = 3.821, p < 0.05. Specifically, high motivational intensity emotions elicited significantly higher P2 amplitudes than low motivational intensity emotions, suggesting that high motivational intensity requires a greater allocation of cognitive resources.

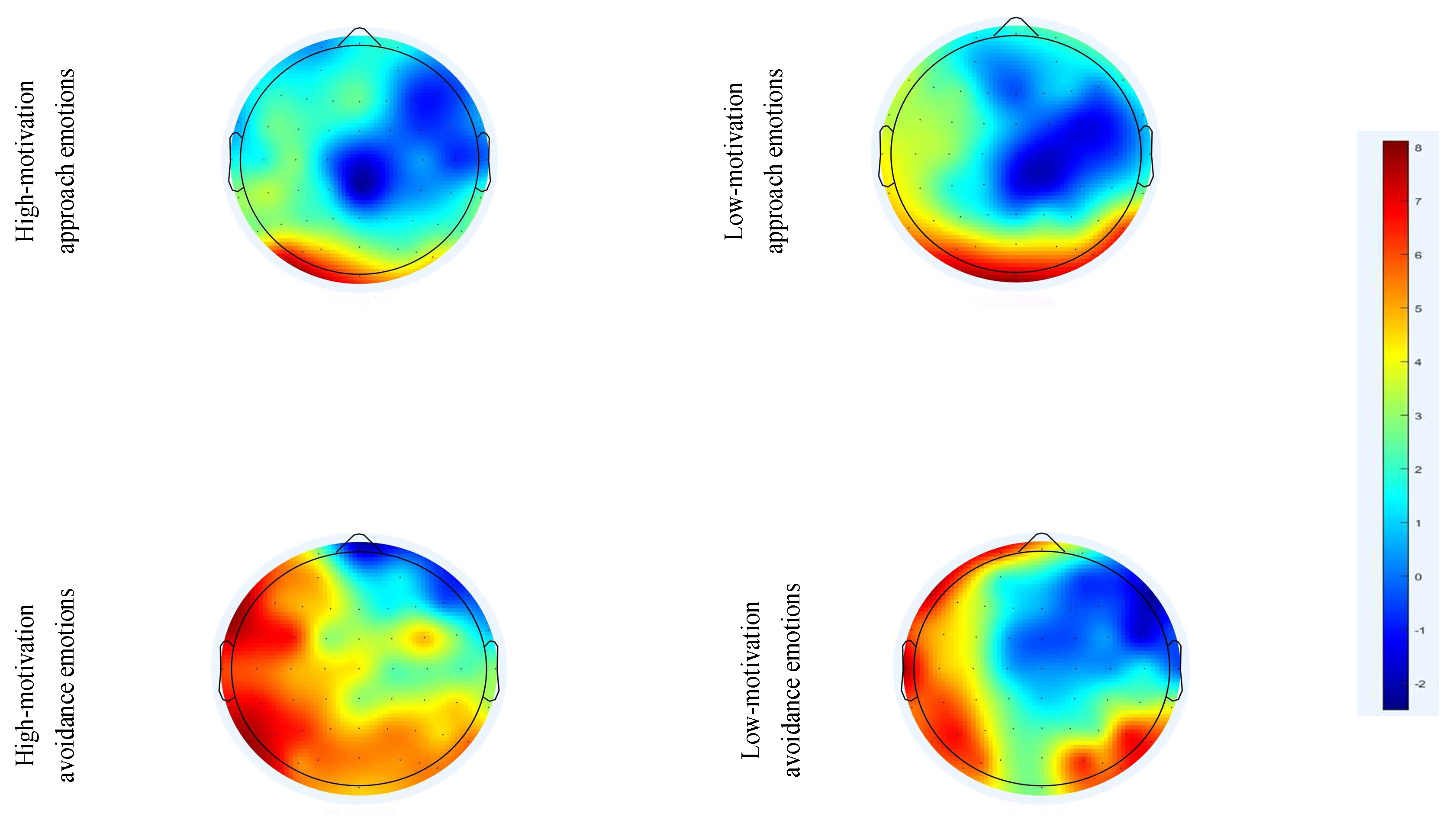

Figure 5.

Brain topography of P2 component.

Figure 5.

Brain topography of P2 component.

In summary, emotional motivational intensity significantly affects the P2 amplitude, but the interactions with other factors were not significant.

(2) P2 Latency

A three-factor repeated measures ANOVA on P2 latency was conducted with emotional motivational intensity(high vs. low), emotional motivational direction (approach vs. avoidance), and electrode position as within-subject factors.

The analysis revealed a significant main effect of emotional motivational intensity, F(1,59) = 5.123, p < 0.05,η²= 0.162. Specifically, high motivational intensity emotions elicited significantly longer P2 latencies than low motivational intensity emotions, which is consistent with the cognitive resource allocation theory that posits stronger emotions require more cognitive resources, thereby delaying processing.

In contrast, the main effect of emotional motivational direction was not significant, F(1,59) = 1.137, p > 0.05,η² = 0.041, suggesting that the influence of approach versus avoidance on P2 latency is relatively weak. Additionally, a significant main effect of electrode position was found, F(3.456,203.728) = 4.012, p < 0.05,η²= 0.721, indicating that P2 latency was most pronounced at electrode positions over the central parietal area, underscoring the key role of these regions in processing emotional information.

No significant interaction effects were observed among emotional motivational intensity, direction, and electrode position, implying that their individual effects on P2 latency are largely independent. Consequently, future studies should prioritize examining the independent contributions of these factors rather than their interactions when investigating the P2 component.

3.2.3. N2 Component

(1) N2 Average Amplitude

A three-factor repeated measures ANOVA was conducted on the average amplitude of the N2 component to examine the effects of emotional motivational direction, intensity, and electrode site. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of emotional motivational direction, F(1,59) = 3.284, p < 0.05, indicating that the N2 amplitude elicited under approach motivation was significantly lower (i.e., more negative) than that under avoidance motivation. This suggests that approach motivation is associated with a stronger neural response during early attentional processing. In contrast, the main effect of emotional motivational intensity was not significant, F(1,59) = 2.591, p > 0.05, indicating that motivational intensity has a relatively minor impact on the N2 amplitude.

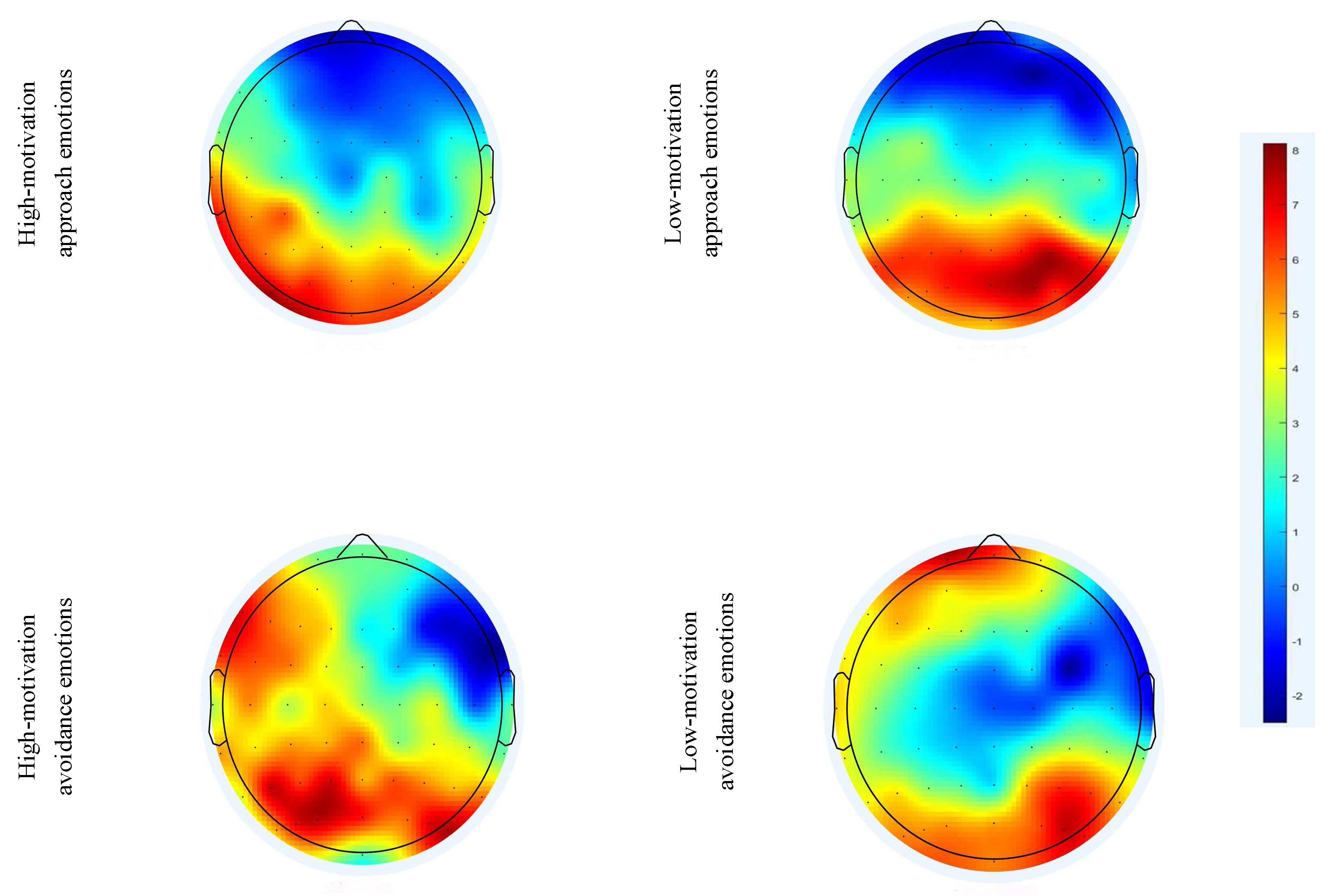

The main effect of electrode position was significant, F(3.174,203.728) = 4.762, p < 0.05,η²= 0.814, indicating that there are significant differences in the distribution of the N2 component across various brain regions, as illustrated in

Figure 6. Specifically, the N2 amplitude was most pronounced in the right frontal area (F4, FC4, C4), consistent with previous research that highlights the key role of the right frontal region in processing emotional and motivational information. Additionally, the interaction effects between emotional motivational intensity, motivational direction, and electrode position were not significant (p > 0.05).

In summary, while emotional motivational direction significantly influenced the N2 amplitude when considered independently, its effect did not remain significant in interaction with other factors. Therefore, when investigating the N2 component, research should primarily focus on the independent effects of variables such as emotional motivational direction rather than on their interactions.

(2) N2 Latency

A three-factor repeated measures ANOVA on the N2 component latency revealed a significant main effect of emotional motivational direction, F(1,59) = 4.205, p < 0.05, η² = 0.158. Post-hoc tests indicated that the latency for emotions induced by avoidance motivation (314.849 ± 3.731 ms) was significantly longer than that for approach motivation (309.397 ± 3.898 ms). This suggests that miners require additional time for initial information processing when encountering avoidance emotions, which aligns with evolutionary psychology theories proposing that individuals allocate extra cognitive resources to process potential threats to ensure survival.

The main effect of emotional motivational intensity was not significant (F(1,59) = 0.065, p > 0.05), indicating that N2 latency is predominantly influenced by the direction of motivation rather than its intensity. In contrast, the main effect of electrode position was significant, F(4.703,276.487) = 7.795, p < 0.01,η²= 0.262. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the N2 latency was longest in the right frontal lobe area (specifically at FCz, C4, and FC3), underscoring the key role of this region in emotional processing.

The interaction effects between emotional motivational direction and intensity, as well as with electrode position, were not significant (p>0.05), and the three-way interaction was also not significant (p>0.05). Therefore, when studying the N2 component, the focus should be on the independent influence of emotional motivational direction rather than on its interaction effects.

3.2.4. P300 Component

(1) P300 Average Amplitude

A three-factor repeated measures ANOVA on the average amplitude of the P300 component revealed a significant main effect of emotional motivational direction, F(1,59) = 3.147, p<0.05,η²= 0.122. Specifically, avoidance-motivated emotions elicited higher P300 amplitudes than approach-motivated emotions, suggesting that individuals allocate more attentional resources to cope with potential threats under avoidance motivation.

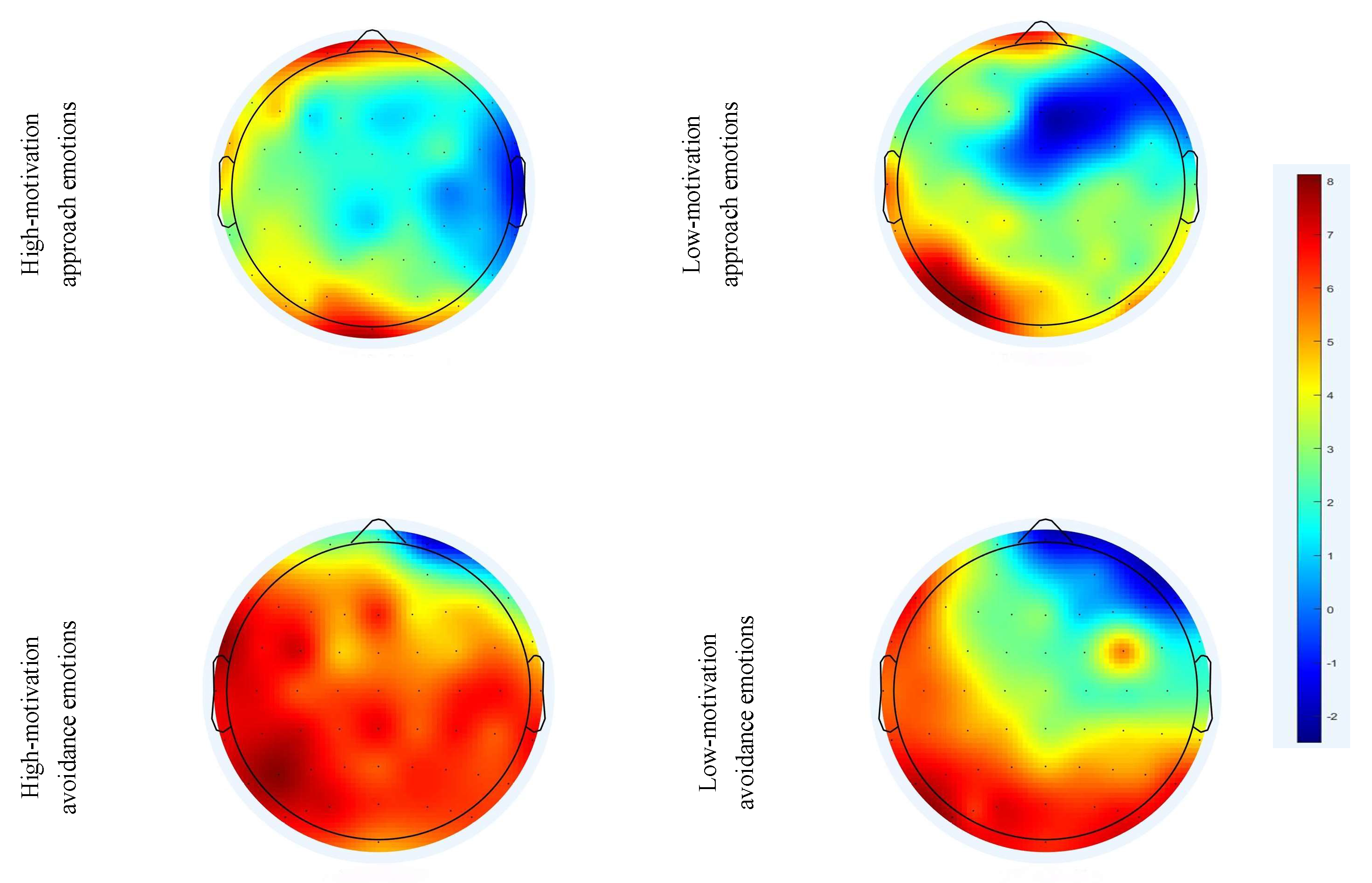

The main effect of emotional motivational intensity was not significant, F(1,59) = 1.459, p>0.05. As illustrated in

Figure 7, topographic map analysis revealed that the P300 amplitude was most prominently activated in the right frontal brain region (F4, FC4, Fz). This finding is consistent with related studies, suggesting that this region plays a crucial role in the allocation of attentional resources and the processing of emotional information.

The main effect of electrode position was significant, F(3.032, 178.298) = 7.503, p < 0.05, η² = 0.255, with the strongest P300 amplitude activation observed in the right frontal area. Interaction analyses revealed that the interactions between emotional motivational intensity and motivational direction, as well as between these factors and electrode position, were not significant (p>0.05).

In summary, emotional motivational direction and electrode position have a significant impact on the P300 amplitude, but their interaction is not significant, thus more attention should be paid to the effects of independent factors.

(2) P300 Latency

A three-factor repeated measures ANOVA on the latency of the P300 component revealed a significant main effect of emotional motivational direction, F(1,59) = 2.517, p < 0.05,η²=0.231.Specifically,the P300 latency was significantly longer for avoidance-motivated emotions than for approach-motivated emotions. This suggests that individuals require more time to process emotional information when in an avoidance state, reflecting a delayed response to potential threats or negative stimuli.

The main effect of emotional motivational intensity was not significant, F(1,59) = 0.022, p>0.05, suggesting that motivational intensity has a minimal impact on P300 latency. This may be because the P300 component primarily reflects processes related to attention resource allocation and memory updating, which are not directly modulated by the intensity of motivation.

The main effect of electrode position was significant, F(5.487, 325.712) = 7.145, p < 0.01,η²=0.238. Notably, the P300 latency was longest in the right frontal brain area (specifically at electrodes FCz, C4, and FC3), indicating that this region plays a crucial role in the allocation of emotional and attentional resources.

Interaction analyses revealed that the interactions between emotional motivational intensity and motivational direction, as well as between these factors and electrode position, were not significant (p > 0.05). Therefore, although emotional motivational direction and electrode position independently affect P300 latency, their combined effects are not significant. Future research should thus focus on the independent contributions of these factors.

3.2.5. LPP Components

(1) Average Amplitude of the LPP

A three-factor repeated measures ANOVA on the average amplitude of the LPP component revealed a significant main effect of emotional motivational direction, F(1,59) = 4.329, p<0.05,η²= 0.132. Specifically, the LPP amplitude elicited by avoidance-motivated emotions was significantly higher than that elicited by approach-motivated emotions. This finding suggests that under avoidance emotional motivation, individuals allocate more attentional resources to processing emotional information, thereby eliciting a stronger emotional response.

The main effect of emotional motivational intensity was not significant, F(1,59) = 2.437, p > 0.05, suggesting that motivational intensity exerts a relatively minor influence on the LPP amplitude. This indicates that motivational intensity primarily affects the sustained processing stage of emotional stimuli rather than the immediate attentional allocation.

The main effect of electrode position was significant, F(2.042, 118.498) = 7.912, p < 0.01,η²= 0.263. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the LPP amplitude was most pronounced in the right frontal brain area (as indicated by electrodes F3, FC3, and FCz), suggesting that this region plays a key role in emotional processing and the allocation of attentional resources.

Interaction analyses revealed that the interactions between emotional motivational intensity, motivational direction, and electrode position were not significant (p > 0.05). Therefore, the focus should be on independently analyzing the main effects of emotional motivational direction and electrode position, rather than on their interactions.

(2) Latency of LPP

A three-factor repeated measures ANOVA was conducted on the average amplitude of the LPP component. The results revealed a significant main effect of emotional motivational direction, F(1,59) = 4.329, p < 0.05, η² = 0.132, with avoidance-motivated emotions eliciting a significantly higher LPP amplitude than approach-motivated emotions. This finding suggests that under avoidance emotional motivation, individuals allocate more attentional resources to processing emotional information, resulting in a stronger emotional response.

In contrast, the main effect of emotional motivational intensity was not significant, F(1,59) = 2.437, p > 0.05, indicating that motivational intensity has a relatively minor impact on the LPP amplitude and primarily affects the sustained processing stage of emotional stimuli.

Additionally, the main effect of electrode position was significant, F(2.042,118.498) = 7.912, p < 0.01, η² = 0.263, with the strongest LPP amplitude observed in the right frontal brain area (specifically at F3, FC3, and FCz). This suggests that the right frontal region plays a key role in emotional processing and the allocation of attentional resources.

Interaction analyses showed that the interactions between emotional motivational intensity and motivational direction, as well as with electrode position, were not significant (p > 0.05). Therefore, the focus should be on independently analyzing the main effects of emotional motivational direction and electrode position rather than on their interactions.