Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Structural formulae |  |

| Molecular formulae | C16H18ClN3S |

| IUPAC systemic name | [7-(Dimethylamino)phenothiazin-3-ylidene]-dimethylazanium chloride |

| Synonyms | Aizen methylene blue; Basic blue 9 (8CI); Calcozine blue ZF; Chromosmon; C.I. 52 015; Methylthionine chloride; Methylthioninium chloride; Phenothiazine5-ium,3,7-bis, (dimethylamino)-, chloride; Swiss blue; Tetramethylene blue; Tetramethyl thionine chloride |

| Relative molecular mass | 319.85 a.m.u. |

| Description | Dark green crystals or crystalline powder with bronze lustre, odourless, stable in air, deep blue solution in water or alcohol, forms double salts |

| Density | 1.0 g/mL at 20 °C |

| Solubility | 43.6 g/L in water at 25 °C; also soluble in ethanol |

| pKa | 3.14 to 3.851 |

| Vapour pressure | 1.30 × 10−7 mm Hg at 25 °C |

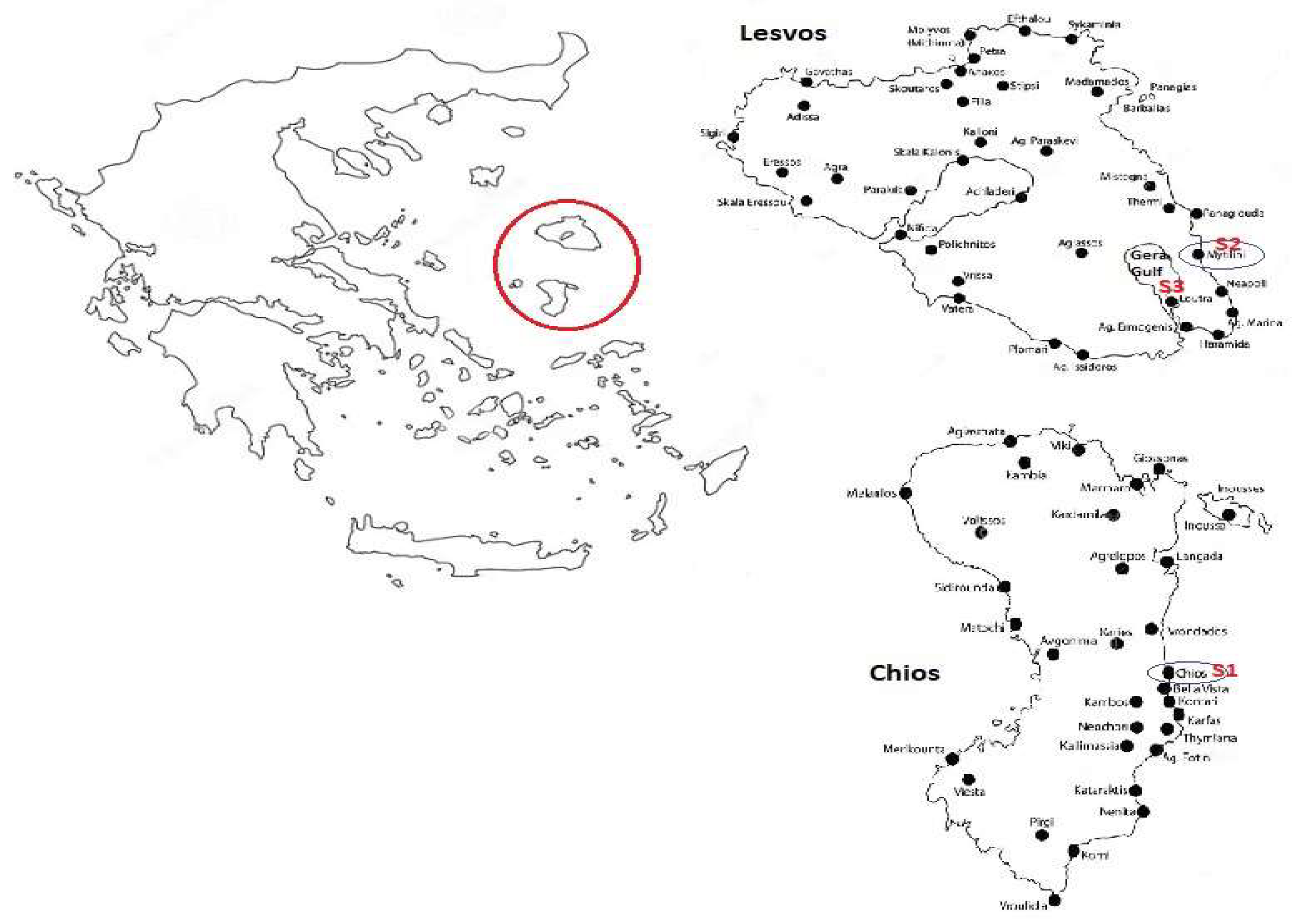

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Adsorption studies

2.2. Desorption studies

3. Results and Discussion

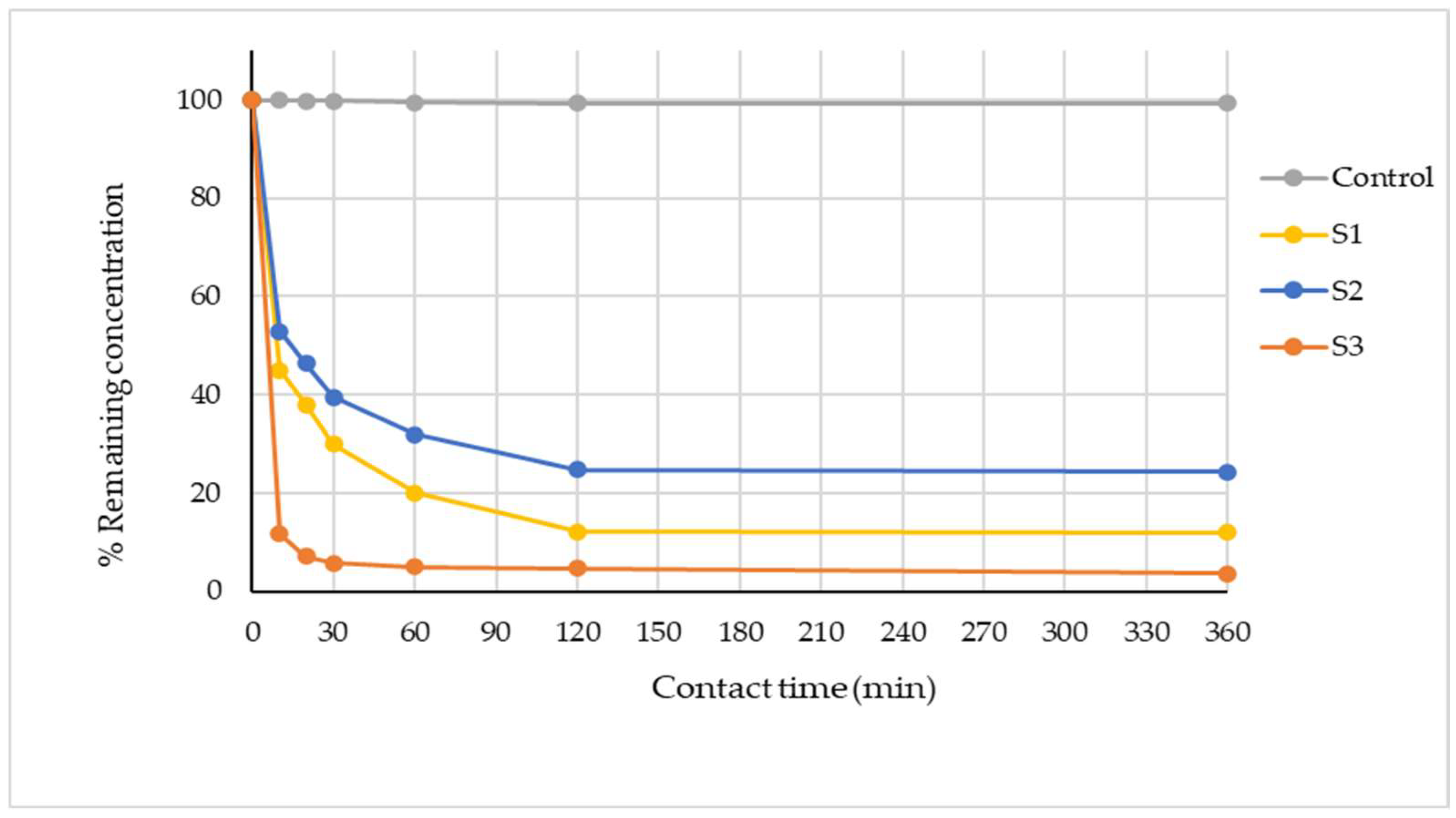

3.1. Adsorption of methylene blue dye onto marine sediments

3.1.1. Effect of contact time

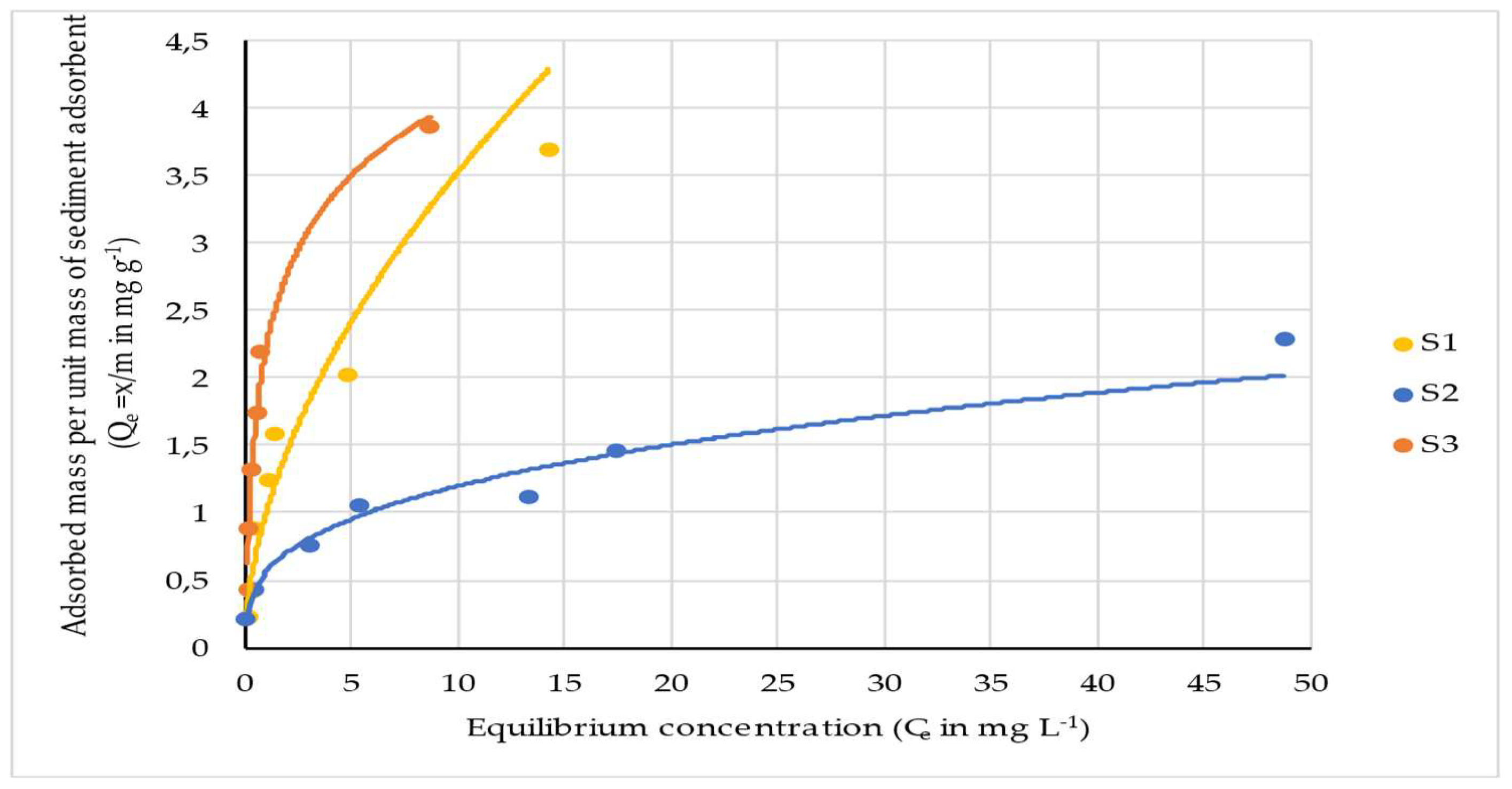

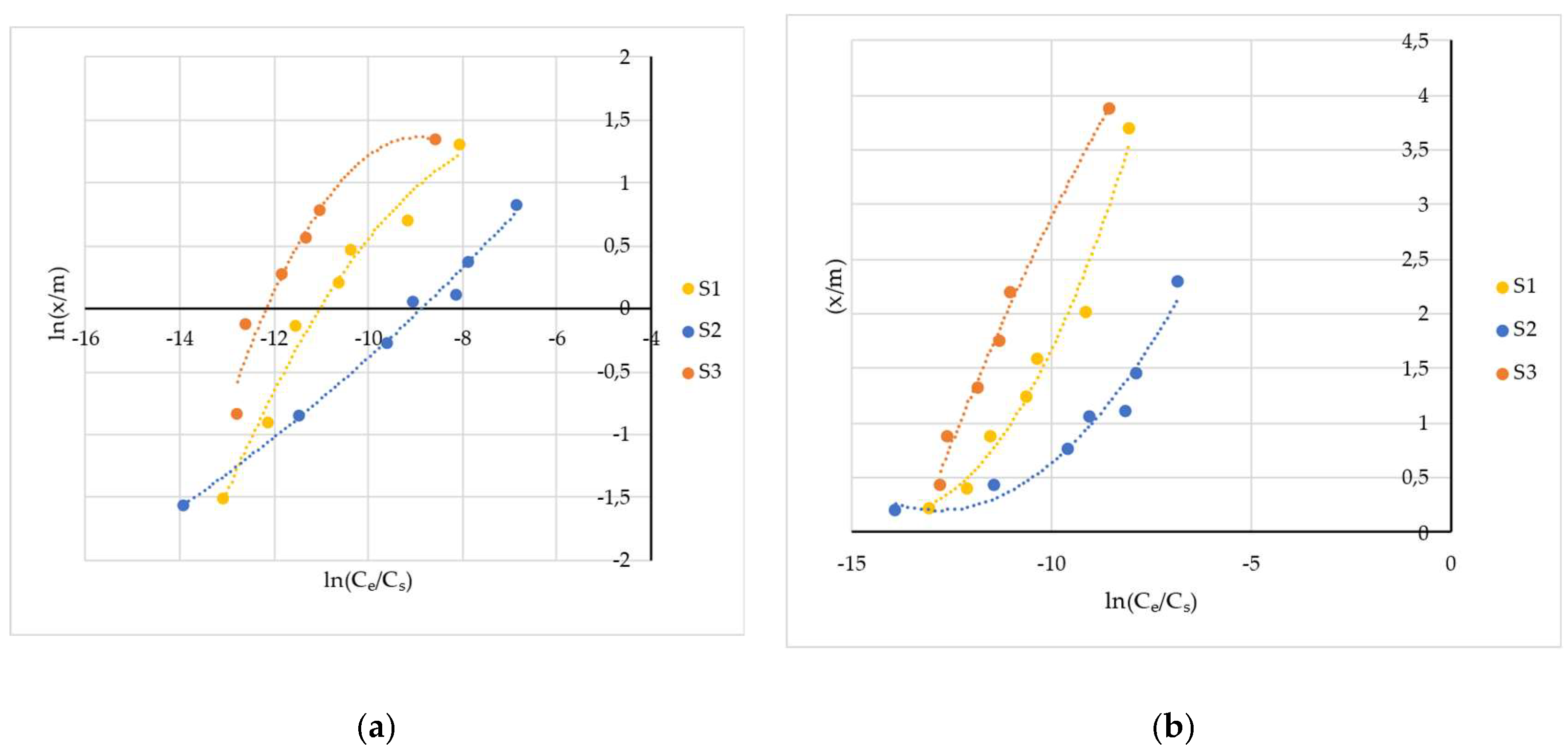

3.1.2. Adsorption isotherms

3.1.3. Kinetics of adsortion

3.1.4. Affinity of studied marine sediments with the MB dye

3.1.5. Mass balances

3.2. Adsorption of methylene blue dye onto seagrass biomass of Posidonia oceanica species

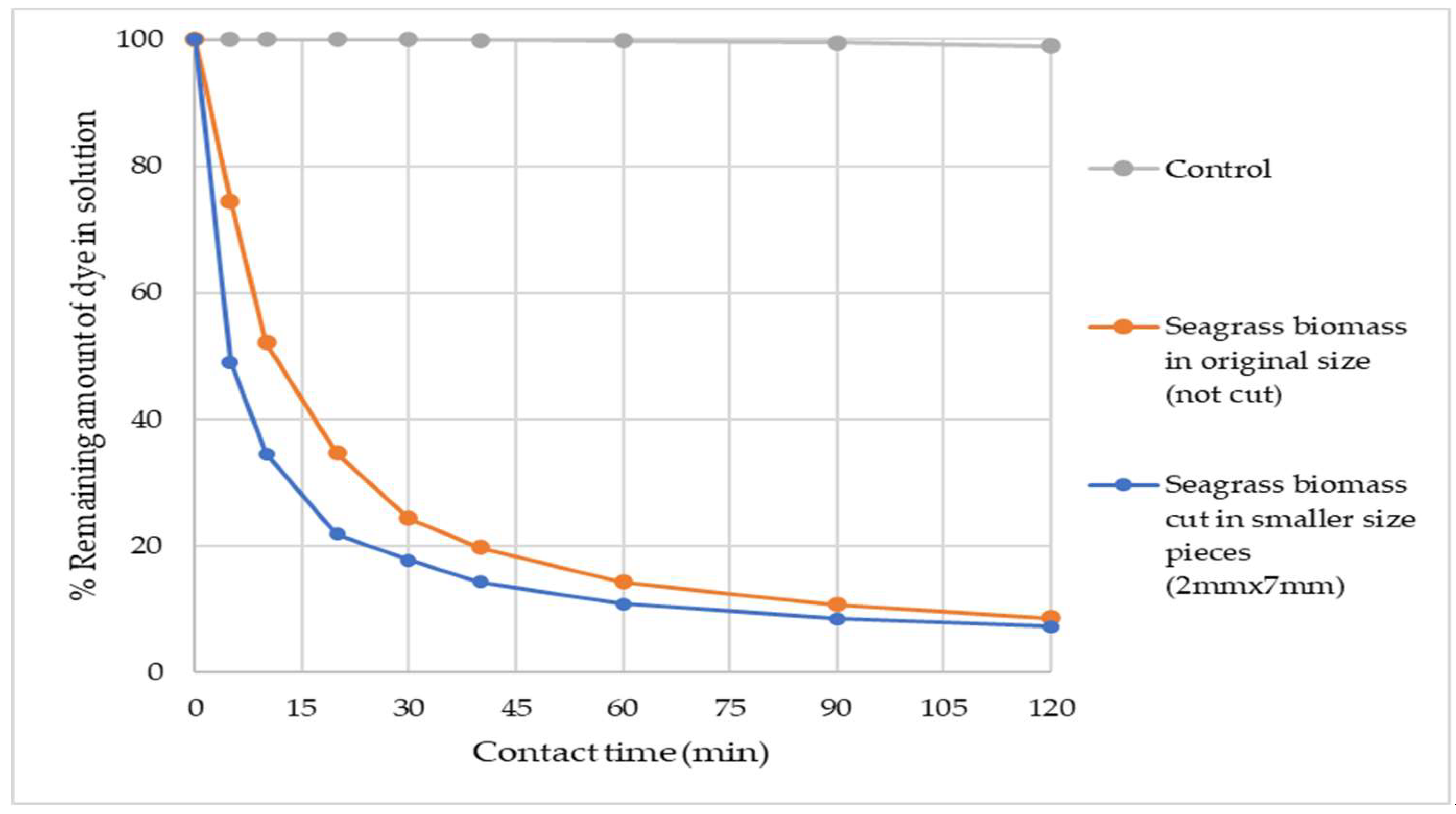

3.2.1. Effect of contact time

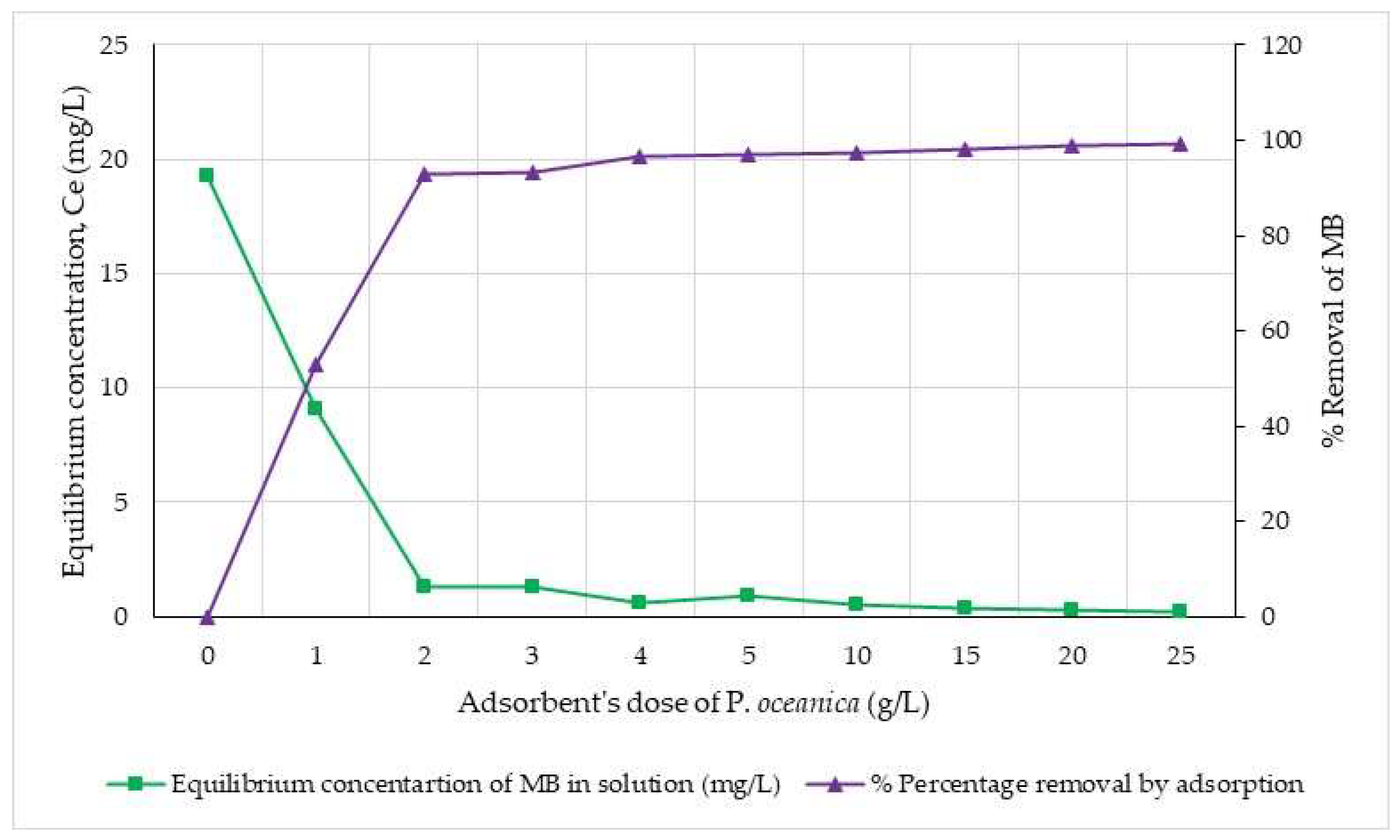

3.2.2. Effect of adsorbent’s dose

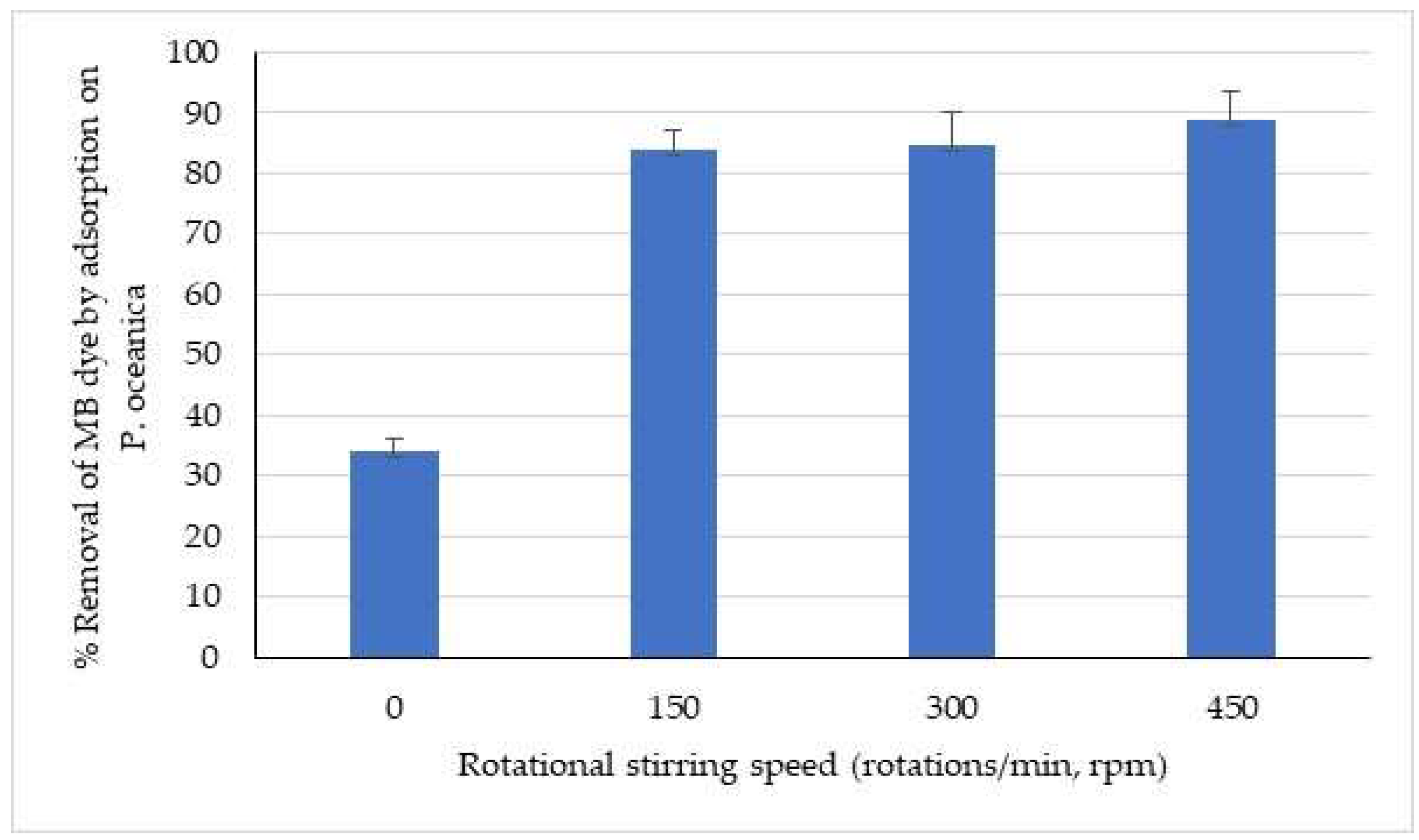

3.2.3. Effect of mechanical rotational stirring speed

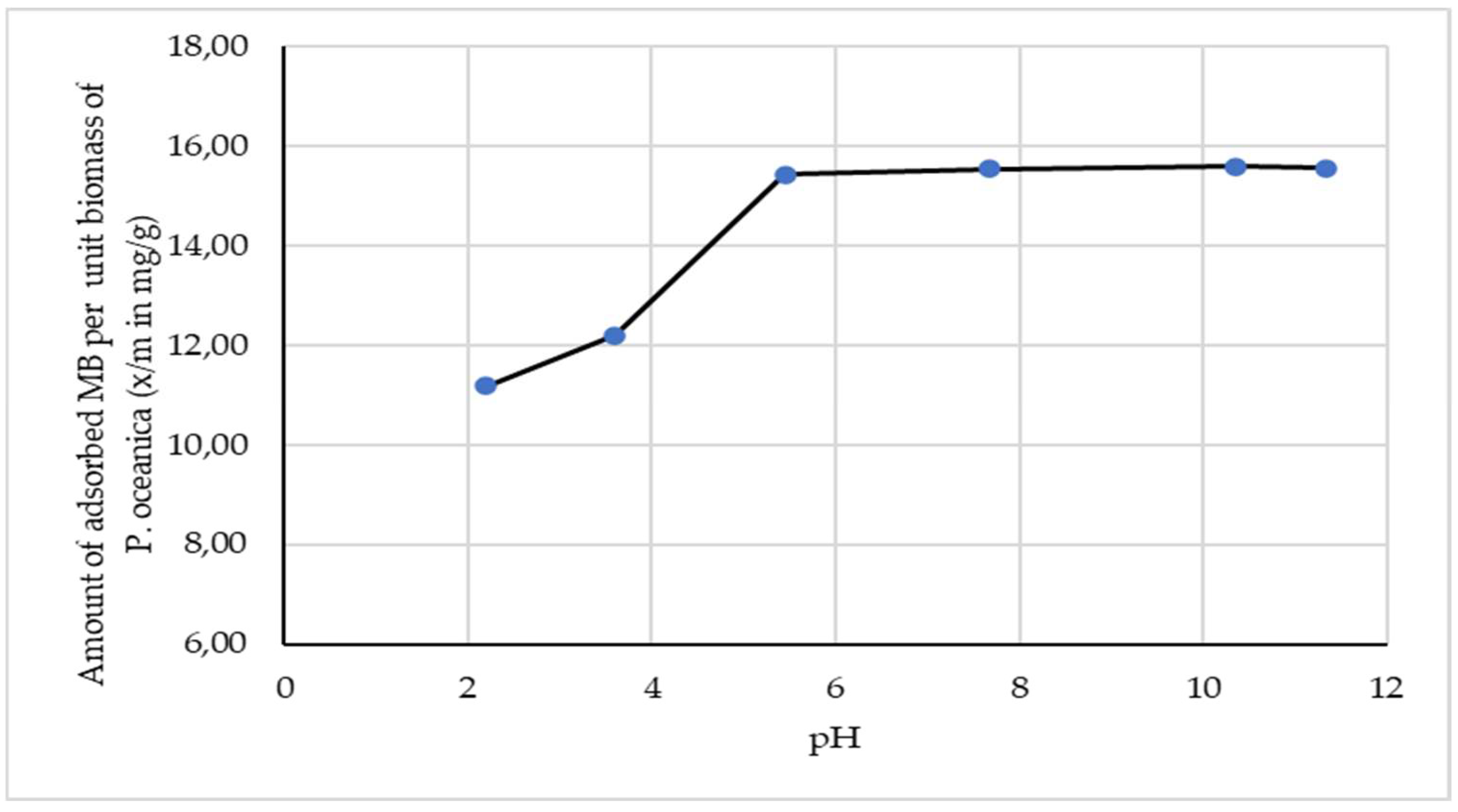

3.2.4. Effect of pH

3.2.5. Adsortion isotherms

3.2.6. Adsorption kinetic modelling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BOD | Biological Oxygen Demand |

| Ce | Equilibrium concentration of methylene blue in the solution (in mg L-1) |

| Ci | Initial concentration of methylene blue in the solution (in mg L-1) |

| Cs | Solubility or saturation concentration (in mg L-1) |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| DO | Dissolved oxygen |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| KF | Freundlich’s isotherm constant (in mg1–1/n g−1 L1/n ) or L mg-1) |

| KH | Henry’s isotherm constant (in L g-1) |

| KL | Langmuir’s isotherm constant (in L mg-1) |

| KOM | Normalized sorption coefficients per 1g of organic matter |

| m | Mass of dry adsorbent (in g) |

| MB | Methylene Blue |

| n | Freundlich exponent related to adsorption intensity (dimensionless) |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Guideline |

| OM | Organic matter |

| pH | Negative logarithm (base 10) of hydrogen ion concentration |

| pKa | Negative logarithm (base 10) of the acid dissociation constant |

| q | Amount of methylene blue adsorbed per unit of mass of dry adsorbent (in mg g-1) |

| qmax | Maximum (monolayer) adsorption capacity of the adsorbent substrate (in mg g-1) |

| R | Universal gas constant (equal to 1.986 cal K-1 mol-1 or 8.314 J K-1 mol-1) |

| R2 | Squared regression correlation coefficient |

| T | Absolute temperature (in K degrees) |

| V | Solution volume (in L) |

| WPWS | Wine-Processing Waste Sludge |

| ΔG | Change in Gibbs free energy (in cal mol-1 or J mol-1) |

| ΔH | Change in enthalpy (in cal mol-1 or J mol-1) |

| ΔS | Change in entropy (in cal mol-1 or J mol-1) |

| θ | Temperature (in oC degrees) |

References

- Chakravarty, P.; Bauddh, K.; Kumar, M. (2015). Remediation of Dyes from Aquatic Ecosystems by Biosorption Method Using Algae. In: Algae and Environmental Sustainability. Developments in Applied Phycology; Singh, B., Bauddh, K., Bux, F., Eds.; Publisher: Springer, New Delhi, 2015; Volume 7, pp. 97–106. [CrossRef]

- Blacksmith Institute Annual Report: 2012 report: the top ten sources by global burden of disease. Available online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blacksmith_Institute#2012_report:_The_Top_Ten_Sources_by_Global_Burden_of_Disease (accessed on 5/2/2025).

- Bouras, H.D.; Isik, Z.; Arikan, E.B.; Yeddou, A.R.; Bouras, N.; Chergui, A.; Favier, L.; Amrane, A.; Dizge, N. Biosorption characteristics of methylene blue dye by two fungal biomasses. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2020, Volume 78, pp.365–381. [CrossRef]

- Koroglu, E.O.; Yoruklu, H.C.; Demir, A.; Ozkaya, B. Chapter 3.9 - Scale-Up and Commercialization Issues of the MFCs: Challenges and Implications. In Biomass, Biofuels and Biochemicals, Microbial Electrochemical Technology, Venkata Mohan, S., Sunita Varjani, Ashok Pandey, Eds; Elsevier, 2019, pp. 565-583. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-64052-9.00023-6 (accessed on 15/1/2025). [CrossRef]

- Alves de Lima, R.O.; Bazo, A.P.; Salvadori, D.M.F.; Rech, C.M.; de Oliveira Palma, D., Umbuzeiro, G.A. Mutagenic and carcinogenic potential of a textile azo dye processing plant effluent that impacts a drinking water source. Mut. Res./Gen. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2007, Volume 626, pp.53–60. [CrossRef]

- Oplatowska, M.; Donnelly, R.F.; Majithiya, R.J.; Kennedy, D.G.; Elliott, C.T. The potential for human exposure, direct and indirect, to the suspected carcinogenic triphenylmethane dye Brilliant Green from green paper towels. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, Volume 49, pp.1870–1876. [CrossRef]

- Chia, M.A.; Musa, R.I. Effect of indigo dye effluent on the growth, biomass production and phenotype plasticity of Scenedesmus quadricauda (Chlorococcales). An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2014, Volume 86(1), pp. 419–428.

- Ratna, R.; Padhi, B.S. Pollution due to synthetic dyes toxicity & carcinogenicity studies and remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, Volume 3(3), pp. 940-955.

- Suteu, D.; Zaharia, C.; Bilba, D.; Muresan, A.; Muresan, R.; Popescu, A. Decolorization wastewaters from the textile industry – physical methods, chemical methods. Ind .Text. 2009, Volume 60, pp.254–263.

- Zaharia,C.; Suteu ,D. Textile organic dyes – characteristics, polluting effects and separation/elimination procedures from industrial effluents – a critical overview. In: Organic pollutants ten years after the Stockholm Convention – Environmental and analytical update, 1st ed., Puzyn, T., Mostrag-Szlichtyng A., Eds.; Publisher: InTech, Croatia, 2012, pp 55–86.

- Punzi, M.; Anbalagan, A.; Aragão Börner, R.; Svensson, B.M.; Jonstrup, M.; Mattiasson, B. Degradation of a textile azo dye using biological treatment followed by photo-Fenton oxidation: evaluation of toxicity and microbial community structure. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, Volume 270, pp.290–299. [CrossRef]

- Yagub, M.T.; Sen, T.K.; Afroze, S.; Ang, H.M. Dye and its removal from aqueous solution by adsorption: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, Volume 209, pp. 172-184. [CrossRef]

- Vagi, M.C.; Leventelli M.; Petsas, A.S. Adsorption-desorption of methylene blue dye onto marine sediments: Kinetics and equilibrium studies. In Proceedings of 18th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, Athens, Greece, (30 August to 2 September 2023).

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Zekker, I.; Zhang, B.; Hendi, A.H.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, S.; Zada, N.; Ahmad, H.; Shah, L.A.; et al. Review on Methylene Blue: Its Properties, Uses, Toxicity and Photodegradation. Water, 2022, Volume 14, Article ID 242. [CrossRef]

- Rafatullah, M.; Sulaiman, O.; Hashim, R.; Ahmad, A. Adsorption of methylene blue on low-cost adsorbents: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, Volume 177, pp. 70–80. [CrossRef]

- Santoso, E.; Ediati, R.; Kusumawati, Y.; Bahruji, H.; Sulistiono, D.O.; Prasetyoko, D. Review on recent advances of carbon based adsorbent for methylene blue removal from waste water. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, Volume 16, Article ID 100233. [CrossRef]

- Mashkoor, F.; Nasar, A. Magsorbents: Potential candidates in wastewater treatment technology—A review on the removal of methylene blue dye. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, Volume 500, Article ID 166408. [CrossRef]

- Zamel, D.; Khan, A.U. Bacterial immobilization on cellulose acetate based nanofibers for methylene blue removal from wastewater: Mini-review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, Volume 131, Article ID 108766. [CrossRef]

- Dra, A.; Tanji, Κ.; Arrahli, A.; Iboustaten, Ε.Μ.; Gaidoumi, A. Ε.; Kherchafi, A.; Chaouni Benabdallah, A.; Kherbeche ,A. Valorization of Oued Sebou Natural Sediments (Fez-Morocco Area) as Adsorbent of Methylene Blue Dye: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Study. Sci. World J. 2020, Volume 2020, Article ID 2187129. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L-F.; Wang, H.-H.; Lin, K.-Y.; Kuo, J.-Y.; Wang, M.-K.; Liu, C.-C. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution using sediment obtained from a canal in an industrial park. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, Volume 78(3-4), pp. 556-570. [CrossRef]

- Global Chemical Network (ChemNet). Available online: https://www.chemnet.com (accessed on 15/1/2025).

- National Toxicology Program (NTP). Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of methylene blue trihydrate (Cas No. 7220–79–3) in F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice (gavage studies). Natl Toxicol Program Tech Rep Ser. 2008 May; 540, 1–224. PMID:18685714. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18685714/ (accessed on 15/1/2025).

- PubChem Open Chemistry Database at the National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information. Methylene blue. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 15/1/2025).

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjiareff method for determining soil organic matter and a proposed modification of chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, Volume 37, pp. 29-38.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Test No. 106: Adsorption-Desorption Using a Batch Equilibrium Method. In OECD Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals, Section 1. OECD Publishing, Paris. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264069602-en (accessed on 15/1/2025). [CrossRef]

- Vagi, M.C.; Petsas, A.S.; Kostopoulou, M.N.; Lekkas, T.D. Adsorption and desorption processes of the organophosphorus pesticides, dimethoate and fenthion, onto three Greek agricultural soils. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2010, Volume 90(3-6), pp. 369-389. [CrossRef]

- Ncibi, M.C.; Mahjoub, B.; Ben Hamissa, A.M.; Ben Mansour, R.; Seffen, M. Biosorption of textile metal-complexed dye from aqueous medium using Posidonia oceanica (L.) leaf sheaths: Mathematical modelling. Desalination 2009, Volume 243, pp. 109-121. [CrossRef]

- Ncibi, M.C.; Ben Hamissa, A.M.; Fathallah, A.; Kortas, M.H.; Baklouti, T.; Mahjoub, B.; Seffen, M. Biosorptive uptake of methylene blue using Mediterranean green alga Enteromorpha spp. J. Haz. Mat. 2009, Volume 170 (2-3), pp. 1050-1055. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hossain, M.F.; Duan, C.; Lu, J.; Tsang, Y.F.; Islam, M.S.; Zhou, Y. Isotherm models for adsorption of heavy metals from water - A review. Chemosphere. 2022, Volume 307, Part 1, Article ID 135545. [CrossRef]

- Vagi, M.C. Hydrolysis and adsorption study of selected organophosphorus pesticides in aquatic and soil systems. Εvaluation of their toxicity on marine algae. phD Thesis, University of the Aegean, Department of Environment, School of Environment, Mytilene, Lesvos, 2007. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10442/hedi/17779(accessed on 6/2/2025) (in Greek, 355 pages).

- Kannan, N.; Sundaram, M.M. Kinetics and mechanism of removal of methylene blue by adsorption on various carbons—A comparative study. Dyes Pigments 2001, Volume 51, pp. 25–40.

- Ncibi, M.C.; Mahjoub, B.; Seffen, M. Kinetic and equilibrium studies of methylene blue biosorption by Posidonia oceanica (L.) fibres. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, Volume 139(2), pp. 280–285. [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918,40 (9), pp. 1361–1403.

- Kaewsarn, P.; Yu, Q. Cadmium removal from aqueous solutions by pretreated biomass of marine algae Padina sp. Environ. Pollut. 2001, Volume 112, pp. 209–213.

- Rashid, J.;Tehreem, F.; Rehman, A.; Kumar, R.. Synthesis using natural functionalization of activated carbon frompumpkin peels for decolourization of aqueous methylene blue. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, Volume 671, pp. 369–376.

- Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y. Adsorption of methylene blue by coal-based activated carbon in high-salt wastewater. Water, 2022, Volume 14(21), Article ID 3576. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, S. Adsorption of methylene blue in water onto activated carbon by surfactant modification. Water, 2020, Volume 12(2), Article ID 587. [CrossRef]

- Waranusantigul, P.; Pokethitiyook, P.; Kruatrachue, M.; Upatham, E.S. Kinetics of basic dye (methylene blue) biosorption by giant duckweed (Spirodela polyrrhiza). Environ. Pollut. 2003, Volume 125, pp. 385–392.

- El Sikaily, A.; Khaled, A.; El Nemr, A.; Abdelwahab, O. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution by marine green alga Ulva lactuca. Chem. Ecol. 2006, Volume 22(2), pp. 149–57.

- Caparkaya, D.; Cavas, L. Biosorption of methylene blue by a brown alga Cystoseira barbatula Kutzing. Acta Chim. Slov. 2008, Volume 55, pp. 547–553.

- El Atouani, S.; Belattmania, Z.; Reani, A.; Tahiri, S.; Aarfane, A.; Bentiss, F.; Zrid, R.; Sabour, B. Brown seaweed Sargassum muticum as low-cost biosorbent of Methylene blue. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2019, Volume 13, pp. 131–142.

- Bouzikri, S.; Ouasfi, N.; Benzidia, N.; Salhi, A.; Bakkas, S.; Khamliche, L. Marine alga “Bifurcaria bifurcata”: Biosorption of Reactive Blue 19 and methylene blue from aqueous solutions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, Volume 27, pp. 33636–33648. [CrossRef]

- Lebron, Y.A.R.; Moreira, V.R.; Santos, L.V.S. Studies on dye biosorption enhancement by chemically modified Fucus vesiculosus, Spirulina maxima and Chlorella pyrenoidosa algae. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, Volume 240, Article ID 118197.

- Pathak, V.V., Kothari, R., Chopra, A.K., Singh, D.P. (2015). Experimental and kinetic studies for phycoremediation and dye removal by Chlorella pyrenoidosa from textile wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, Volume 163, pp. 270-277.

- Santaeufemia, S.; Abalde, J.; Torres, E. Efficient removal of dyes from seawater using as biosorbent the dead and living biomass of the microalga Phaeodactylum tricornutum: equilibrium and kinetics studies. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, Volume 33, pp. 3071–3090. [CrossRef]

- Marungrueng, K.; Pavasant, P. High performance biosorbent (Caulerpa lentillifera) for basic dye removal. Biores. Technol. 2007, Volume 98(8), pp. 1567–1572.

- Rubin, E.; Rodriquez, P.; Herrero, R.; Cremades, J.; Barbara, I.; Sastre de Vicente, M.E. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions using as biosorbent Sargassum muticum: an invasive macroalga in Europe. J. Chem. Technol.Biotechn. 2005, Volume 80(3), pp. 291–298. [CrossRef]

- Vilar, V.J.P.; Botelho, C.; Boaventura, R.A.R. Methylene blue adsorption by algal biomass-based materials: biosorbents characterization and process behaviour. J. Hazard. Mat. 2007, Volume 147(1), pp. 120–132. [CrossRef]

- Dra A., Tanji Κ., Arrahli A., Iboustaten Ε.Μ., Gaidoumi A. Ε., Kherchafi A., Chaouni Benabdallah A., Kherbeche A., (2020). Valorization of Oued Sebou Natural Sediments (Fez-Morocco Area) as Adsorbent of Methylene Blue Dye: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Study. Sci. World J. 2020, Volume 2020, Article ID 2187129. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Li, Y.S.; Chen, Y.M.; Li, H.H.; Wang, M.K. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution using wine-processing waste sludge. Wat. Sci. Technol. 2012, Volume 65 (12), pp. 2191–2199. [CrossRef]

| Sediment sample | Textural analysis (%) | Organic matter content (%)1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 63-2000 μm | <63μm | ||

| S1 | 98.32 | 1.68 | 2.94 |

| S2 | 93.76 | 6.24 | 1.70 |

| S3 | 65.46 | 34.54 | 5.38 |

| S1 | S2 | S3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co (mg L-1) |

Ce (mg L-1) |

q (mg g-1) |

Co (mg L-1) |

Ce (mg L-1) |

q (mg g-1) |

Co (mg L-1) |

Ce (mg L-1) |

q (mg g-1) |

| 5 | 0,10 | 0,22 | 5 | 0,04 | 0,21 | 10 | 0,13 | 0,44 |

| 10 | 0,25 | 0,41 | 10 | 0,49 | 0,43 | 20 | 0,15 | 0,88 |

| 20 | 0,45 | 0,88 | 20 | 3,07 | 0,76 | 30 | 0,33 | 1,32 |

| 30 | 1,11 | 1,24 | 30 | 5,36 | 1,06 | 40 | 0,56 | 1,75 |

| 40 | 1,45 | 1,59 | 40 | 13,37 | 1,11 | 50 | 0,75 | 2,20 |

| 50 | 4,86 | 2,02 | 50 | 17,35 | 1,46 | 100 | 8,66 | 3,87 |

| 100 | 14,25 | 3,70 | 100 | 48,76 | 2,29 | |||

| Freundlich Isotherm Model | |||

| Parameter (units) |

S1 sediment sample |

S2 sediment sample |

S3 sediment sample |

| KF (L mg−1) | 1.0049 | 0.5623 | 1.8576 |

| n | 1.8315 | 3.0414 | 2.2267 |

| R2 | 0.9659 | 0.9644 | 0.9004 |

| Langmuir Isotherm Model | |||

| Parameter (units) |

S1 sediment sample |

S2 sediment sample |

S3 sediment sample |

|

qmax (mg g-1) |

2.5907 | 0.9827 | 6.7981 |

| KL (L mg-1) | 6.2246 | 6.1419 | 30.6359 |

| R2 | 0.9829 | 0.8884 | 0.8487 |

| HenryIsotherm Model | |||

| Parameter (units) |

S1 sediment sample |

S2 sediment sample |

S3 sediment sample |

| KH (L g-1) | 0.2897 | 0.0553 | 0.4837 |

| R2 | 0.8474 | 0.8399 | 0.6949 |

| Sediment sample | KOM |

ΔG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (cal mol-1) | (J mol-1) | ||

| S1 | 34,1803 | -2.062,07 | -8.627,70 |

| S2 | 33,0765 | -2.042,91 | -8.547,53 |

| S3 | 34,5279 | -2.067,98 | -8.652,42 |

| Sediment Sample | Loading Level (mg g-1) |

(%) Adsorbed | (%) Free or not adsorbed | (%) Desorbed1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.225 | 98.06 | 1.94 | 0.09 (0.09) |

| 0.45 | 97.49 | 2.51 | 0.21 (0.22) | |

| 0.9 | 97.75 | 2.25 | 0.22 (0.22) | |

| 1.35 | 96.28 | 3.72 | 0.54 (0.56) | |

| 1.8 | 96.38 | 3.62 | 0.48 (0.50) | |

| 2.25 | 90.28 | 9.72 | 1.02 (1.13) | |

| 4.5 | 85.75 | 14.25 | 1.62 (1.89) | |

| S2 | 0.225 | 99.17 | 0.83 | 0.09 (0.09) |

| 0.45 | 95.15 | 4.85 | 0.14 (0.14) | |

| 0.9 | 84.65 | 15.35 | 0.11 (0.13) | |

| 1.35 | 82.13 | 17.87 | 0.23 (0.28) | |

| 1.8 | 66.58 | 33.42 | 0.16 (0.25) | |

| 2.25 | 65.30 | 34.70 | 0.21 (0.32) | |

| 4.5 | 51.24 | 48.76 | 0.38 (0.73) | |

| S3 | 0.225 | 99.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 (0.00) |

| 0.45 | 98.72 | 1.28 | 0.01 (0.01) | |

| 0.9 | 99.24 | 0.76 | 0.09 (0.09) | |

| 1.35 | 98.91 | 1.09 | 0.15 (0.15) | |

| 1.8 | 98.61 | 1.39 | 0.17 (0.17) | |

| 2.25 | 98.51 | 1.49 | 0.19 (0.19) | |

| 4.5 | 91.34 | 8.66 | 0.68 (0.74) |

| Seagrass biomass of P. oceanica in original size (not cut) | Seagrass biomass of P. oceanica cut into smaller size pieces (2mm width x 7mm length) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co (mg L-1) |

Ce (mg L-1) |

% Removal |

Qe (mg g-1) |

Co (mg L-1) |

Ce (mg L-1) |

% Removal |

Qe (mg g-1) |

| 10 | 0,58 | 94,21 | 4,61 | 10 | 0,42 | 95,85 | 4,70 |

| 20 | 1,92 | 90,39 | 9,13 | 20 | 1,85 | 90,76 | 9,21 |

| 30 | 2,45 | 91,50 | 13,89 | 30 | 2,13 | 92,90 | 13,55 |

| 40 | 3,33 | 91,68 | 19,84 | 40 | 2,59 | 93,52 | 20,29 |

| 50 | 3,22 | 93,56 | 22,71 | 50 | 5,10 | 89,80 | 21,77 |

| Freundlich Isotherm Model | ||

| Parameter (units) | Seagrass biomass of P. oceanica in original size (not cut) | Seagrass biomass of P. oceanica cut into smaller size pieces (2mm width x 7mm length) |

| KF (L mg-1) | 0.1357 | 0.0593 |

| n | 0.9424 | 0.7247 |

| R2 | 0.9194 | 0.7777 |

| Langmuir Isotherm Model | ||

| Parameter (units) | Seagrass biomass of P. oceanica in original size (not cut) | Seagrass biomass of P. oceanica cut into smaller size pieces (2mm width x 7mm length) |

|

qmax (mg g-1) |

13.245 | 17.857 |

| KL (L mg-1) | 0.0095 | 0.0008 |

| R2 | 0.9131 | 0.9606 |

| HenryIsotherm Model | ||

| Parameter (units) | Seagrass biomass of P. oceanica in original size (not cut) | Seagrass biomass of P. oceanica cut into smaller size pieces (2mm width x 7mm length) |

| KH (L g-1) | 0.1444 | 0.2073 |

| R2 | 0.9241 | 0.7735 |

| Adsorbent Material | Maximum adsorption capacity qmax (in mg g-1) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Posidonia oceanica | 13.24-17.86 | Present Study |

| Posidonia oceanica | 5.56 | [32] |

| Enteromorpha spp. | 274 | [28] |

| Spirodela polyrrhiza | 144.93 | [38] |

| Ulva lactuca | 40.2 | [39] |

| Cystoseira barbatula | 38.61 | [40] |

| Sargassum muticum | 191.38 | [41] |

| Bifurcaria bifurcata | 2,744.5 | [42] |

| Fucus vesiculosus | 698.477 | [43] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | 20.8-21.3 | [44] |

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | 18.5-18.9 | [45] |

| Caulerpa lentillifera | 417 | [46] |

| Sargassum muticum | 279.2 | [47] |

| Algae Gelidium | 171 | [48] |

| Algal waste | 104 | [48] |

| Composite material with polyacrylonitrile | 74 | [48] |

| Marine sediment (collected from unpolluted coastal areas of Chios, North Aegean, Greece) | 0.9827 | Present Study |

| Marine sediment (collected from unpolluted coastal areas of Mytilene, Lesvos, North Aegean, Greece) | 2.5907 | Present Study |

| Marine sediment (collected from a marine aquaculture industry, Selonda, Gera’s Golf, Lesvos North Aegean, Greece) | 6.7981 | Present Study |

| Sediment obtained from a canal in an industrial park (Ekman dredge, Taipei City, Taiwan) | 56,0 | [20] |

| River sediment (Sebou River, Morocco) | 3,24 | [49] |

| Wine-processing waste sludge | 285.7 | [50] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).