Introduction

What are these needs? The new data can provide an analytical tool to answer that question. To use that tool, however, we must first define the newly emerging human needs of the different areas and their relation to each other. Human needs may be studied from many different perspectives, since our current understanding of human irrationality today not only accepts as fact the possibility of cognitive biases, fallacies, and delusions influencing human decisions and needs, but also recognizes the value of individual self-awareness of human irrationality, associated needs, and decision making that we might call ’irrational.’[

1] Also, various conscious human needs cannot be called rational or irrational, so here we will rather call them ’neutral’ or ’ambivalent.’ It is also important to take into account the impact of changes in the hierarchy of human needs from generation to generation throughout the lives of individuals, their ancestors, and the impact of this on their descendants. For a correct understanding, it is also important to remember that the presented names of areas of human needs are taken here only for description and do not describe the nature of their benefit or harm, which is usually used in a completely different meaning and context.

Genetic Determination

The fact that the psychological and social problems of a person throughout their life are determined by the ancestors of that person, through genetical information transmitted to an individual today, is not a subject of doubt.[

2,

3,

4] However, no previous research has attempted to go beyond the study of individual negative or positive loyalty to certain conditions. Furthermore, no single study examined the influence of loyalty on unfilled or overfilled needs transferred to the individual, in contrast to studies of a person’s loyalty to poverty or wealth, or a person’s happiness or unhappiness.[

5,

6,

7] This study attempts to go even further and assume that the individual’s hierarchical order of needs is also genetically determined by the intentions and needs of their own ancestors. And this, of course, can be logically indicated by the data from the same kind of studies.[

8,

9,

10] Since numerous psycho-medical practices and studies also indicate that when an individuals found that they were identified with their relatives, they often got rid of not only troubles and anxiety, but also excessive needs or apathy as well.[

11,

12,

13] This clearly demonstrates that an individual can also inherit the needs and intentions from ancestors, as well as overfilled ones. As is known from the basics of epigenetics, the genome of an individual throughout a person’s life is also subject to numerous changes that the person’s descendants can also inherit, thus enclosing the whole circle.

The New Dynamic Model of Motivation and Human Needs

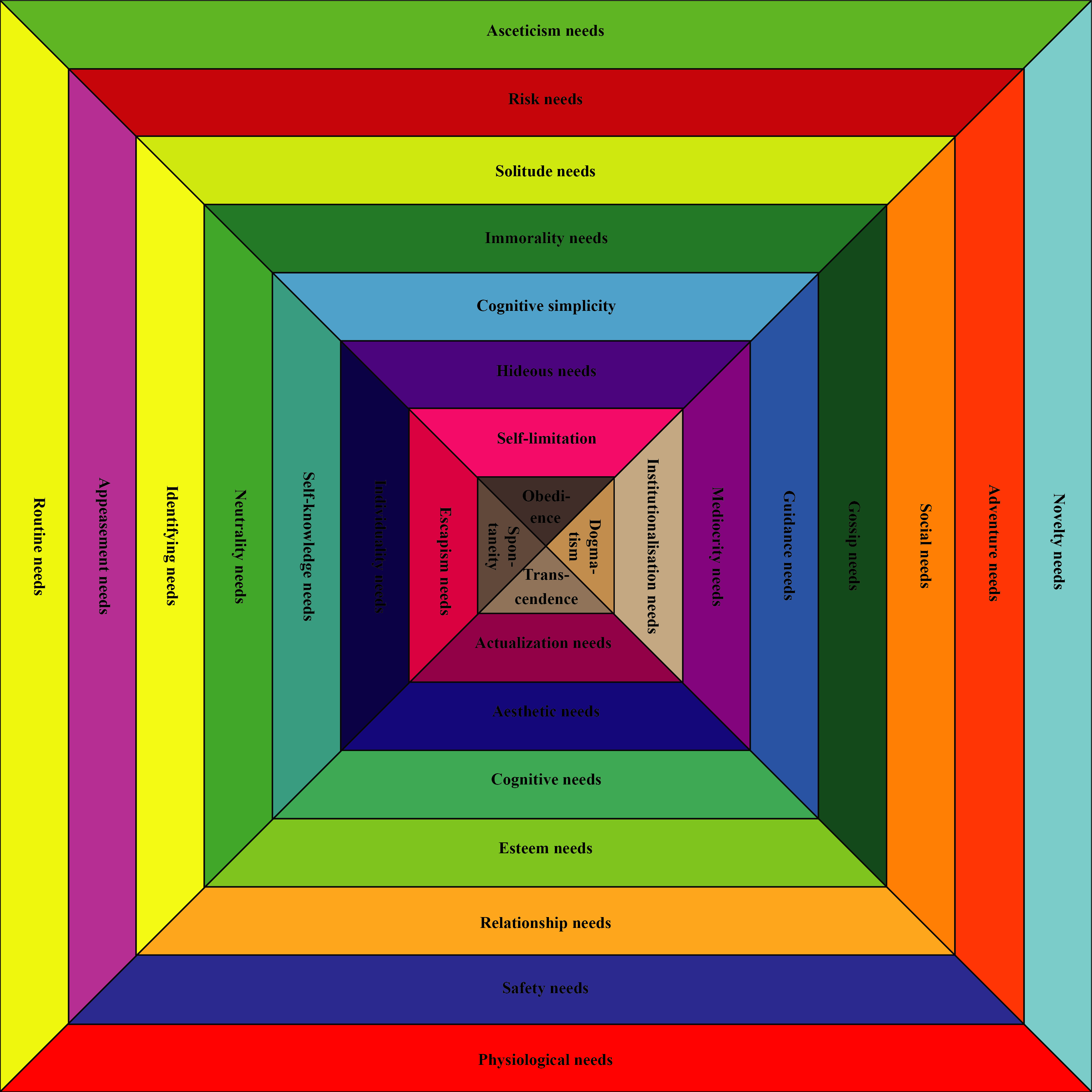

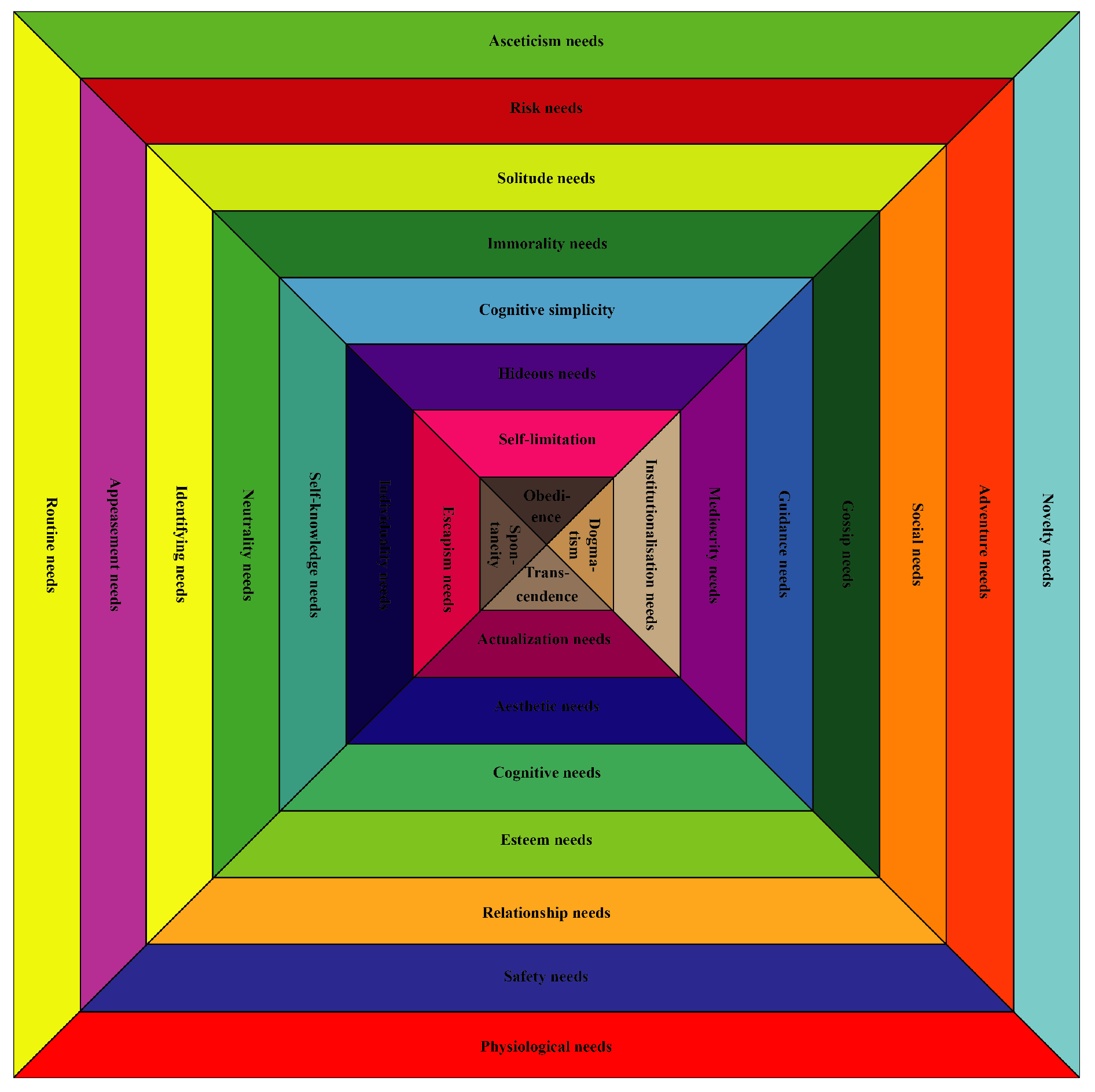

The model of motivation and human needs given, created for the sake of this study, was further exhibited by the 4 areas of human needs, each consisting of 8 needs, relatively associated with that area, thus creating the 32 human needs in total.

Figure 1.

The new dynamic model of motivation and human needs

Figure 1.

The new dynamic model of motivation and human needs

Rational Needs

This area of the presented human motivational and needs model consists of the original Maslow’s Hierarchy of 8 Needs, taken here, of course, in its more contemporary, but conceptually unchanged form.[

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] This model was taken here as a basis due to its time-tested nature and the absence of any incompleteness in relation to this area. Being a generally accepted model of motivation, it was also able to fill this area of human needs without any shortcomings in the new model created for the purposes of this study. This hybrid model not only reached the desired justice with the subject of study, but also enabled a distinct direction and perspective toward understanding human motivation and needs. This was achieved without compromising the thoroughness and integrity embedded in Maslow’s original hierarchy.[

19]

Irrational Needs

This area is based on a compilation of the opposites to 8 human needs, listed in a newer iteration of the Maslow’s model, taken here as a basis. This area consists of human needs, which we had called here ’irrational.’

Asketism Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for minimalistic life, self-discipline, and avoiding all forms of indulgence. Although there is no specific study that demonstrates a human need for asketism, there is a growing body of research that suggests that living with fewer possessions and prioritizing simplicity can have a positive impact on well-being and quality of life. Which may also indicate the existence of such needs. For example, a study published in the Journal of Consumer Research found that people who focus on material possessions experience lower levels of happiness and life satisfaction compared to those who prioritize personal growth and relationships.[

20] Another study published in the Journal of Positive Psychology found that people who practice minimalism experience higher levels of gratitude and life satisfaction.[

21] Other studies have also shown that practicing mindfulness can lead to better emotional regulation, reduced stress and anxiety, and increased well-being.[

22] Additionally, research has found that engaging in acts of self-discipline can increase feelings of self-efficacy and self-esteem.[

23] Although these findings do not directly address asceticism, they do suggest that practicing minimalism can have positive effects on mental and emotional well-being, which can also indirectly confirm the existence of the corresponding human need.

Risk Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for risky actions and activities. Although humans do have a need for safety and security, there is also evidence to suggest that we have a need for risk and challenge. In fact, some research has shown that taking calculated risks and facing challenges can actually enhance our well-being and satisfaction in life. For example, a study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that people who engage in activities that involve risk and challenge experience higher levels of flow, a psychological state characterized by heightened focus, engagement, and enjoyment.[

24] Another study published in the Journal of Positive Psychology found that people who pursue goals that are challenging and meaningful experience greater levels of well-being and life satisfaction compared to those who pursue easier, less meaningful goals.[

25] So these studies can clearly demonstrate that while it is important to be mindful of our need for safety and security, it is also important to recognize our need for risk and challenge in order to live a fulfilling and meaningful life.

Solitude Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for solitude. There is a growing body of research that highlights the importance of solitude and the human need for it. Here, only a few studies are taken here as an example to demonstrate the benefits of solitude and its importance for human beings. This study explores the role of solitude in promoting self-awareness, creativity, and personal growth.[

26] This study examines the relationship between solitude and psychological well-being, and finds that solitude can have a positive impact on mental health.[

27] This study investigates the effects of solitude on cognitive and emotional well-being, and finds that solitude can improve cognitive performance and reduce stress.[

28] This study explores the neural mechanisms underlying the human need for solitude, and finds that solitude can have a positive impact on brain function and well-being.[

29] This study examines the cultural and historical context of solitude, and argues that solitude is essential for living a fulfilling and meaningful life.[

30] This study explores the paradox of solitude, and argues that being alone can be beneficial for mental health and well-being.[

31] This study examines the relationship between solitude and creativity, and finds that solitude can be an essential component of the creative process.[

32] This study investigates the relationship between solitude and mental health and finds that solitude can have a positive impact on mental health and well being.[

33] These studies clearly demonstrate that solitude is not only a natural human need, but also a valuable resource to promote self-awareness, creativity, and well-being.

Immorality Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for immoral actions and activities, or, the ones that society or an individual personally considers (imagines) a like. While humans do have social and esteem needs, there is also evidence to suggest that we have a need for immoral and asocial actions. There is plenty of research that highlights the importance of immorality and the human need for it. And here only a few studies are taken here as an example to demonstrate its importance for human beings. Such as the article published in the journal Psychoanalytic Psychology, which challenges readers to rethink their assumptions about human morality and the nature of immoral behavior, and provides valuable insights into the psychological and social factors that contribute to moral hypocrisy while exploring the concept of moral hypocrisy and its implications for our understanding of human morality.[

34] In which the author, as well, examines the structure and meaning of moral hypocrisy, arguing that it is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that can arise from a variety of psychological and social factors. In this article the author also explores the psychological and social factors that contribute to moral hypocrisy, such as the desire for social approval, the fear of punishment, and the influence of social norms. It argues that moral hypocrisy can be both harmful and adaptive, depending on the context in which it occurs. Finally there is discussion of the implication of its findings for our understanding of human morality, suggesting that moral hypocrisy is a common and natural aspect of human behavior. It argues that by acknowledging and understanding the complexities of moral hypocrisy, we can better understand the nature of human morality and develop more effective strategies for promoting moral behavior. Or this article, which explores the question of why individuals might choose to act immorally, despite the potential negative consequences.[

35] Where an author argues that there are several reasons why individuals might choose to act immorally, including the desire to gain power or status, the desire to avoid punishment, and the belief that morality is subjective and relative. This article also examines the idea that immoral behavior can be justified by the desire to achieve a greater good, such as the greater happiness of oneself or others. He argues that this justification is flawed, as it ignores the harm that immoral behavior can cause to others and the fact that there are often alternative, moral ways to achieve the same goals. Overall, the article provides a nuanced and thought-provoking exploration of the reasons why individuals might choose to act immorally, and challenges readers to consider the implications of their actions for themselves and others. Lastly this article examines the idea that immoral actions can be rational, as argued by philosopher Michael Smith. An author also argues that Smith’s view is problematic because it implies that individuals can act immorally without being irrational, which could lead to a moral relativism that undermines the notion of objective moral standards. Overall, it provides a thought-provoking critique of Smith’s view and contributes to the ongoing debate about the nature of morality and rationality. These studies demonstrate that immorality is not only a natural human need, but also an important factor in human decisions and lives.[

36] Which also clearly demonstrates how important is finding safe ways to fulfill such needs, safe and harmless both for an individual and for others.[

37]

Cognitive Simplicity

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for oversimplification. There is a growing body of research that shows that thinking that requires less effort and is simpler is preferable for human to more complex thinking patterns, even when its accuracy is strongly discounted. This may also indicate the existence of such needs. There are only a few studies taken here, which clearly confirm this. Such as this article[

38] This study found that people prefer simpler cognitive structures, such as categorical thinking, over more complex ones, even when the complex structure is more accurate. The authors suggest that this preference is due to the cognitive effort required to process complex information. Another study, which today is already called a classic, found that people tend to prefer simpler options over more complex ones, even when the simpler option is not the best choice. The authors suggest that this is because simpler options are easier to process and require less cognitive effort.[

39] One study examines the problem of cognitive load in the education process and demonstrates that cognitive load, or the amount of mental effort required to complete a task, can have a significant impact on learning.[

40] When cognitive load is too high, learners may experience cognitive overload and be less likely to retain information. However, when the cognitive load is manageable, learners are more likely to engage in deep learning strategies and retain information more effectively. One research even demonstrates the benefits of simplicity in thinking.[

41] This study found that people who use cognitive simplification techniques, such as categorization and labeling, experience cognitive benefits, including improved memory and problem-solving abilities. The authors suggest that these techniques can help individuals to better manage complex information and make more effective decisions. So, despite the shortcomings of this need and the cognitive distortions associated with it, we must still consider its importance in people’s lives, sometimes even positive ones.

Hideous Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for hideous things, or the ones that society or an individual personally considers a like. Although humans do have a need for arts and aesthetics, there is also evidence to suggest that we have a need for something that is aesthetically ugly, hideous, or disgusting. In fact, some research has shown that opposed or previously observed disgust can actually enhance our enjoyment from various art forms, such as abstract and grotesque. One article examines that disgust comes in many varieties, including the humorous, the horrid, and the tragic. The responses it generates can be strong or subtle, but few are actually pleasant.[

42] Other studies have laid out the circumstances under which disgust can be actually experienced as pleasant.[

43] Although disgust itself is not a positive emotion, its influence intensifies other emotions experienced by a person. This may be a good explanation of the need to seek out something disgusting - in this case we are seeing a phenomenon of the same kind as an increased sense of security and well-being after exposure to fictional horror.[

44,

45]

Self-Limitation

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for ’the comfort zone’, or, state that an individual personally considers as such. Plenty of research has shown that humans have an inherent desire for a comfortable and predictable environment, which is essential for our well-being and stress management. Studies have demonstrated that exposure to novel or challenging situations can activate the body’s stress response and that individuals tend to seek out situations that are within their comfort zone to avoid feelings of anxiety or discomfort. Such as studies related to hikikomori phenomenon.[

46,

47,

48,

49] However, there are the obvious negative consequences of the lack of a comfortable predictable environment for the individual and the positive ones in satisfying this need.[

50,

51] So, despite the existence of extreme cases associated with this need, the importance of finding a balance between its sufficient and excessive realization for well-being in an individual’s life itself becomes obvious.

Obedience

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for subordination, or state, actions, and activities that an individual personally considers a like. While humans do have an inherent need to seek transcendence, there is also evidence to suggest that we have a need for obedience and subordination. In fact, some research has shown that participating in subordinate activity can actually overwhelm the participant’s own sense of morality. Such as this classical study, which examined the related dangers of subordination.[

52]Or a research that highlighted that obedience should not be understood as requiring direct orders from an authority figure.[

53] As well, there are studies examining conditions at which subordination can be beneficial.[

54,

55,

56] Or a study examining its relation to other animals.[

57] These studies demonstrate that the need for subordination or transfer the choice or will of an individual to the will of another is obvious. Even if the subordination can be beneficial under certain conditions, when the boundaries set by individuals are not overcome, it is also important to remember about one’s own morality and evaluation about these acts and not participate in dangerous and harmful subordination.

Ambivalent Needs

To date, a great deal of evidence has been accumulated indicating that people have needs and motives that cannot be attributed to the previous two areas, due to their opportunistic origin and consequent results, highly dependent on circumstances and capable of being quite unexpected even for the individual.[

58,

59,

60] This area consists of human needs, which we called here ’ambivalent.’

Novelty Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for anything new. According to research, humans have an inherent desire for new experiences and stimuli, which can be linked to the release of dopamine in the brain. This desire for novelty can manifest itself in various ways, such as looking for new hobbies, traveling, or trying new foods. There are numerous studies that support this idea and here only a few of them are taken, for example, including a study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology that found that people are more likely to engage in novel activities when they feel a sense of boredom.[

61] Another study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin found that people who are more open to new experiences tend to be more creative and have a greater sense of well-being.[

62] Other studies have already tested the need for novelty as a potential need in the theory of basic psychological needs, having already come to affirmative conclusions on this matter before.[

63,

64] This shows that the validity of this statement had already been clearly demonstrated even before the time of this writing.

Adventure Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for adventures, or for the actions, activities and such events, or state of the things that an individual personally considers as such. Despite the sufficient lexical and essentially clear definition for this need, it is very difficult to find evidence of its existence separately from situations of realization of the needs for risk or novelty at the same time. However, the guideline here can be the individual’s sense of dare and courage, sometimes against self, and positive expectations in the upcoming experience, significantly exceeding risks expected. In either case, there is plenty of research showing that humans have a desire for novelty, excitement, and challenge that can be satisfied through adventure. This desire, as well, is thought to be linked to the release of dopamine in the brain. Here are a few examples of studies that demonstrate human need for adventure. Such as a study examining the paradoxical notion of ‘the adventure’ which is sold as a predictable, managed experience-commodity.[

65] Or a study which found that people experience pleasure and enjoyment when engaging in adventurous activities. [

66] One study found that people who engage in adventurous activities, such as hiking or rock climbing, experience a sense of flow, which is a state of complete absorption and engagement in an activity. The study suggests that this sense of flow is linked to increased happiness and well-being.[

67] These studies suggest that humans have an inherent need for adventure. So, despite the problems with defining the boundaries of this need, its very presence becomes obvious.

Social Responsibility

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for events and activities related to a person’s society and social responsibility, or for the actions, activities and events that an individual personally considers a like. According to research, humans have an inherent desire to contribute to the greater good and have a positive impact on society. Here are only a few examples of studies that highlight the importance of social responsibility. Such as this study, which found that people are motivated to engage in prosocial behavior, such as volunteering or donating to charity, because it enhances their sense of self-worth and provides a sense of purpose.[

68] Another study found that consumers are more likely to support companies that are socially responsible and have a positive impact on society.[

69] One study found that employees who work for companies with a strong culture of social responsibility are more motivated and have higher job satisfaction.[

70] Finally, this study found that companies that incorporate social responsibility into their organizational identity are more likely to attract and retain top talent.[

71] These studies demonstrate the importance of social responsibility for individuals and organizations, and highlight the positive impact it can have on motivation, job satisfaction, and organizational success, clearly showing the corresponding need.

Gossip Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for gossip or for conversations of the kind that an individual personally considers a like. While gossip is often viewed as a negative behavior, research suggests that it serves several important social functions and is a fundamental aspect of human communication. Here are a few examples of studies that highlight the importance of gossip. One study found that gossip serves an important social function by allowing individuals to share information about others and maintain social norms.[

72] Another one identified several functions of gossip, including the sharing of information, the establishment of social norms, and the maintenance of social relationships.[

73] Another study found that gossip can be used as a means of social control, allowing individuals to influence the behavior of others and maintain social order.[

74] There is also research examining the psychological aspect of gossip.[

75] This study found that gossip is often used as a way to establish and maintain social relationships, and those individuals who engage in gossip are more likely to have larger social networks. These studies suggest that gossip is an important aspect of human communication and serves several social functions. While excessive or malicious gossip can be harmful, it is clear that gossip and the need for it play a significant role in human social behavior.

Guidance Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for guidance. Humans have an inherent need for guidance and direction, and this need is evident throughout our lives. Here are only a few examples of studies that highlight the importance of guidance. One study highlights that guidance is essential for children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development. It showed that children who receive guidance from parents, teachers, and other adults are more likely to develop positive outcomes such as academic achievement, social competence, and emotional well-being.[

76] Another study demonstrates that guidance can have a positive impact on student learning outcomes. The study showed that students who received guidance from teachers were more likely to engage in deep learning strategies, such as critical thinking and problem solving, and were more likely to achieve academic success.[

77] There is also a study that demonstrates that guidance is essential for employee success on the job. The study showed that employees who receive guidance from supervisors and mentors are more likely to have higher job satisfaction, better performance, and greater career advancement.[

78] Finally, there is a study demonstrating that humans have a fundamental psychological need for guidance. The study showed that individuals who feel a lack of guidance or direction in their lives are more likely to experience anxiety, stress, and other negative emotions.[

79] These studies demonstrate the importance of guidance in human development, learning, and success. Guidance provides people with the direction, support, and feedback they need to achieve their goals and reach their full potential, clearly showing the corresponding need.

Mediocrity Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need to conform to own notion of mediocrity in such ways as wealth, lifestyle, appearance and behavior, or inconspicuous state. While there may not be specific studies that directly demonstrate a human need for mediocrity, there is research on the importance of social comparison and the impact of perceived average on self-esteem. However, it is important to note that it can also be influenced by cultural and societal factors, and may not be easily applicable. However, the guideline here can be the individual’s desire to be socially inconspicuous, observing socially related norms. One study suggests that people tend to compare themselves with others and use social norms as a reference point for their own abilities and achievements[

80] This can lead to a desire to conform to the perceived average and not stand out and be inconspicuous. Another research also suggest that people tend to evaluate their own appearance in relation to others and strive for a sense of normalcy or averageness, rather than exceptionalism or uniqueness.[

81] Additionally, studies on body image and self-esteem has shown that people are more likely to feel

positive about themselves when they perceive their appearance as average or typical, rather than

deviating significantly from the norm.[

82,

83] While these studies do not directly address mediocrity,

they do suggest that practicing inconspicuousness or typical appearance in a person's behavior can

have a positive impact on mental and emotional well-being, which can also indirectly confirm the

existence of corresponding human need.

Institutionalization Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual's need to conform to institutions associated with

this individual, manifested in ways such as the person's wealth, appearance, and behavior, or, for

state, or things that an individual personally considers a like. Although there may not be specific

studies that directly demonstrate the human need for institutionalization, there is research on the

importance of social structure and the desire for order and stability in human behavior. Studies suggest

that people tend to seek out institutions and social hierarchies as a way to make sense of the world

and their place within it.[

84,

85] Additionally, research on social identity theory and the psychology

of groups has shown that people derive a sense of belonging and selfesteem from their membership

in groups and institutions, and that this can lead to a desire to maintain and reinforce these social

structures.[

86,

87] While the se studies do not directly address institutionalization, they do suggest that

conforming to institutions associated with this individual have a significant impact on mental and

emotional wellbeing, which can also indirectly confirm the existence of corresponding human need.

Dogmatism

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for an ’overvalued (supervalued) idea’, or for a thing, concept, thought, imagining, belief, or an ideas that an individual personally considers as such. There is a great deal of research on the psychology of beliefs and the factors that influence them. Many studies suggest that people tend to hold beliefs that are consistent with their existing values and experiences, as well as that they may be resistant to information that challenges these beliefs. Additionally, research on social influence and group dynamics has shown that people are often influenced by the beliefs and behaviors of those around them and that this can lead to the adoption of dogmatic beliefs.[

88] One study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that people are more likely to accept and remember information that confirms their preexisting beliefs, rather than information that contradicts them.[

89] Another study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology found that people are more likely to engage in motivated reasoning when their beliefs are challenged, leading to the overvaluation of their existing beliefs.[

90] Also, there is research on the human tendency to overvalue certain ideas or beliefs. One study showed that people tend to seek out information that confirms their existing beliefs and values, and discount information that contradicts them, which can lead to the overvaluation of certain ideas or beliefs, even when they are not supported by evidence.[

91] These studies demonstrate that dogmatism with the meaning taken here is an important factor in human decisions and lives, clearly demonstrating the corresponding need.

Neutral Needs

This area is based on research data obtained from various studies that indicate that people have needs and motives that were not previously considered as such due to their neutral and noninterventional nature.[

92,

93,

94] This area consists of human needs, which we call here ’neutral.’

Routine Needs

With the meaning taken here is the individual’s need for ’everyday life’ and routine, such a way of life, or for actions and activities or the state of things that an individual personally considers as such. There is a wealth of research that suggests humans have a fundamental need for routine and structure in their lives. Here are only a few studies that are taken here in order to demonstrate this. Such as this study.[

95] Which found that people have a basic psychological need for structure and order in their lives, and that this need is fulfilled by having routines and rituals. Another study found that having a daily routine can provide a sense of stability and predictability, which can be especially important during times of stress or uncertainty.[

96] One research also found that having a routine can help reduce stress and anxiety and can improve general mental health and well-being.[

97] Furthermore, a study found that having a routine can provide a sense of control and agency, which can be important for our well-being and happiness.[

98] These studies demonstrate the importance of routine in human lives, clearly demonstrating the corresponding need.

Appeasement Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for an appeasement and quietly in life. There is a wealth of research that shows that humans have a fundamental need for appeasement, which also manifests itself in acts of appeasing or calming another person or group in order to avoid conflict or negative consequences. Since the number of studies related to the passive form of this need is too large, and in these cases its action is difficult to separate from the action of other needs, such as safety and physiological (silence) needs, we will consider some studies that demonstrate this need in action. Such as research, which found that people are motivated to appease others in order to avoid conflict and maintain relationship harmony, even if it means sacrificing their own needs and desires. [

99] One study found that people are more likely to appease others when they feel threatened or attacked, to reduce perceived danger and restore peace.[

100] Other research highlighted that appeasement is a common strategy used in social interactions to avoid conflict and maintain relationships.[

101] These studies demonstrate the importance of appeasement in human lives, clearly demonstrating the corresponding need.

Identifying Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need to identify with the likable character or another subject and mentally placing an individual into the same situation in the work of fiction or in real life, in this need, it is also highly interesting that it extends not only to identify with a fictional character, but also to any person, object or subject, considered alive by the individual. Although there is not much study on human need for identifying, examining this phenomenon in general and from the point of view that the individual specifically assumes the feelings experienced by another subject, often only to likable one, and does not directly experience the same, some research highlights on the psychological benefits of identifying with others, such as increased social connection. One study published in the journal Personality and Individual Differences found that people who identified with a character in a story were more likely to exhibit empathetic behavior towards others.[

102] Another study examines empathy for animals.[

103] Also, one research has found that comprehending characters in a narrative fiction appears to parallel the comprehension of peers in the actual world, while the comprehension expository nonfiction shares no such parallels. Therefore, frequent fiction readers can boost or maintain their social skills, unlike frequent nonfiction readers.[

104] Lastly, one study found that when readers or viewers can relate to the characters in a story, they become invested in their journey and are more likely to enjoy the story. This can be achieved through well-developed, relatable characters.[

105] So, despite the difficulty in defining the boundaries of this need in relation to reality or fiction, its very existence becomes obvious.

Neutrality Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need to remain neutral to something or someone, as well as for events, ideas and concepts related. However, it is important to note that neutrality does not mean the absence of all personal opinions or beliefs, but rather the ability to set aside one’s own biases and perspectives to listen to and consider other’s viewpoints. While there is not any specific studies demonstrating a human need for neutrality, some research highlights the importance of setting boundaries and maintaining a sense of detachment in various contexts. For instance, studies have shown that setting boundaries can help individuals maintain their well-being and avoid burnout.[

106,

107] Additionally, some studies have found that practicing detachment can improve decision-making and increase emotional regulation.[

108,

109] However, it is important to note that indifference can be harmful if it leads to a lack of empathy or compassion for others. And a balanced approach that prioritizes setting boundaries while still being open to the needs of others could be more beneficial.[

110] While these findings do not directly address neutrality, they do suggest that setting boundaries and remaining neutral can have positive effects on mental and emotional well-being, which can also indirectly confirm the existence of corresponding human needs.

Self-Knowledge

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for self-knowledge, or for the actions, activities, and events that an individual personally considers related to it. There is a significant body of research that highlights the importance of self-knowledge and its impact on human well-being. And there are only a few taken here to demonstrate the human need for self-knowledge. Such as a study, which found that self-knowledge is positively correlated with life satisfaction and happiness.[

111] Another study found that people are motivated to seek self-knowledge to better understand themselves and improve their lives.[

112] A research found that self-reflection can lead to increased self-awareness, self-acceptance, and self-improvement.[

113] Also, there is a study that found that self-awareness is a key predictor of success in both personal and professional contexts.[

114] Lastly, there is a study that highlights that self-knowledge can improve decision making by helping individuals to better understand their own preferences and biases.[

115] These studies demonstrate that self-knowledge is an essential aspect of human well-being and can have a positive impact on our lives. Satisfying the corresponding need by better understanding ourselves allows us to make better decisions, improve our relationships, set, and achieve our goals.

Individuality Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for personalization, individualization, customization, or uniqueness, manifested in the ways such as the individual’s preferences, choices, appearance, overall style, traits and behavior. There is a great deal of research that highlights the importance of this need and its impact on human well-being. This study found that people have a fundamental psychological need for autonomy, which is the desire to be self-directed and make decisions based on their own preferences and values.[

116] It also found that when people feel their sense of uniqueness is threatened, they can experience negative results, such as decreased motivation and well-being. Another research found that consumers place a high value on individuality and uniqueness in their purchasing decisions and also found that consumers are more likely to engage in conspicuous consumption, or the purchase of luxury goods and services, when they feel that their individuality is being recognized and respected.[

117] Another study found that individuals have a strong desire for personalization, which is the tailoring of products and services to meet their unique needs and preferences. The study also found that personalization can lead to increased customer satisfaction, loyalty, and willingness to pay a premium for products and services.[

118] Some studies found that personalization can have a positive impact on consumer attitudes and behavior, such as greater purchasing intent and loyalty. The study also found that personalization can lead to a sense of ownership and possession, which can increase the perceived value of the product or service.[

119] Lastly there is a study which concludes that personalization can lead to desirable outcomes such as reducing choice overload. However, personalized digital environments without transparency and without the option for users to play an active role in the personalization process can pose a danger to their well-being.[

120] These studies demonstrate the human need for personalization or individualization and the importance of it in consumer behavior. By understanding and addressing this need, businesses can increase customer satisfaction, loyalty, and ultimately their bottom line.

Escapism Needs

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for the seek of distraction and relief from unpleasant realities or a person’s society, especially by seeking sport and entertainment or engaging in fantasy, or the actions and activities, things and events that an individual personally considers a like. There are many studies that suggest that humans have an innate desire for escapism as a coping mechanism for stress, anxiety, and other negative emotions. An example is a study that found that people often engage in escapist behaviors when they feel overwhelmed or stressed.[

121] Or this article, which explores the concept of escapism in the context of digital games. The author argues that digital games can serve as a form of escapism for players, allowing them to temporarily forget about their problems and immerse themselves in a virtual world.[

122] However, it is important to note that excessive escapism can be detrimental to mental health, so it is essential to find a balance, even if the importance and presence of the corresponding need becomes obvious.

Spontaneity

With the meaning taken here as the individual’s need for spontaneous actions and activities, such events and things, or, for the actions and activities, events and things that an individual personally considers a like. These studies suggest that spontaneity is an important aspect of human psychology and that it plays a role in our overall well-being and personal growth. One study found that people have a fundamental psychological need for spontaneity and that this need is distinct from other psychological needs such as the need for structure and predictability, as well as its special relationship to creativity.[

123] Another study found that people who engage in spontaneous activities experience a range of positive outcomes such as increased creativity.[

124] Lastly, one study found that while spontaneity can have positive effects, lack of it can also lead to negative outcomes, such as increased levels of stress and depression.[

125] These studies demonstrate that spontaneity is not only a natural human need, but also an important factor in the quality of human lives.

The Way of Normalization

During the writing of this study, it became obvious that a separate section should be devoted to this topic. The current data related to this section confirm previous predictions about the normalization of human needs due to improvement of the conditions for their implementation, which is exactly what Maslow himself once pointed out. It has long been noted that in one form or another there is an independent natural model of human motivation. This also does not cause contradictions in the fact that the desire for it may be different for each person or that our assumptions about it may not fully correspond to reality. However, the very existence of this alleged model to this day does not raise any doubts. In addition, related studies have shown the regular coincidence of the hierarchy of human needs in individuals in cases of their complete satisfaction within the individuals or cases especially close to that state. There is implicative evidence showing that paradigmatic shifts occur leading to a transformative state from lower-order to higher-order needs. According to the hierarchy of needs, it becomes more discernible to perceive the nurturing effect of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation mechanisms used to achieve long-lasting happiness and well-being.[

126] This, of course, logically indicates that the desire for and a better life normalize the hierarchy of human needs to the standard.[

127]

Conclusion

The research presented was an attempt to provide a better unification of human needs, how they are determined by ancestors, and the connection of all this with the future of a person’s own descendants. Using an interdisciplinary approach that draws on recent discoveries of epigenetics and psychology, it has shed light on the rewarding and sometimes confusing behaviors that stem from these influential factors. This model expands understanding of concepts ranging from cognitive biases intertwined with genetic predisposition to perceptions of environmental factors mediated by embedded genetic code. Representing not only life-affirming needs, but also all the needs that have manifested themselves to date, taken regardless of their benefit or harm. The newly created model of motivation considers the rational, irrational, neutral, and ambivalent areas of human needs in connection with their coevolution and possible normalization throughout the life of each individual.

Discussion

Moving forward with related research, a special focus will be on understanding the shift patterns related to these needs. In addition to addressing thematic interdependencies, the model can provide valuable insights into probable changes that could accumulate as a result of progressive evolution. A transitional pathway, dependent on satisfying needs, is perceived to act as a catalyst to shape future manifestations of these needs.

Notes

The hierarchical order of the human needs presented may not be completely right, which creates a scope for criticism and possible improvement. As well as the names of the human needs and their areas given in the current article may not be the most suitable. Therefore, they also may be renamed by more suitable descriptive terms in the near foreseeable future.

It is also worth remembering that there is the possibility of as yet undiscovered or unmanifested human needs and associated motives that are not listed here and may become apparent in the future. It is not news to anyone that the entire culture of humankind is much younger than its origins, and various hidden properties of humans may not have been able to manifest themselves until now.

Funding

No funding has been received.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

Conflicts of Interest

Author declares that he has no competing interests.

References

- Cusimano, C.; Lombrozo, T. People recognize and condone their own morally motivated reasoning. Cognition 2023, 234, 105379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glausiusz, J. Searching chromosomes for the legacy of trauma. Nature 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, C.E.; Loehlin, J.C. Environmental influences that may precede fertilization: a first examination of the prezygotic hypothesis from maternal age influences on twins. Behavior genetics 1998, 28, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bergh PhD, B. The influence of maternal emotions during pregnancy on fetal and neonatal behavior. Journal of Prenatal & Perinatal Psychology & Health 1990, 5, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Bale, T.L. Epigenetic and transgenerational reprogramming of brain development. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2015, 16, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, B. The wisdom of your cells. How Your Beliefs Control your Biology 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Portin, P. The birth and development of the DNA theory of inheritance: sixty years since the discovery of the structure of DNA. Journal of genetics 2014, 93, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, A. Holocaust survivors pass the genetic damage of their trauma on to their children, researchers find. Mail Online 2015, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, C.; Binder, E.B. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: Review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene–environment interactions, and epigenetics. Experimental neurology 2012, 233, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R.; Daskalakis, N.P.; Bierer, L.M.; Bader, H.N.; Klengel, T.; Holsboer, F.; Binder, E.B. Holocaust exposure induced intergenerational effects on FKBP5 methylation. Biological psychiatry 2016, 80, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, E.J. Epigenetic mechanisms of depression. JAMA psychiatry 2014, 71, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, S.L. The Unsayable: The Hidden Language of Trauma. Psychiatric Services 2007, 58, 1382–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doidge, N. The brain’s way of healing: stories of remarkable recoveries and discoveries; Penguin UK, 2015.

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychological review 1943, 50, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A Dynamic Theory of Human Motivation. 1958.

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of metamotivation: The biological rooting of the value-life. Journal of humanistic psychology 1967, 7, 93–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.; Lewis, K. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Salenger Incorporated 1987, 14, 987–990. [Google Scholar]

- Koltko-Rivera, M.E. Rediscovering the later version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification. Review of general psychology 2006, 10, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noltemeyer, A.; Bush, K.; Patton, J.; Bergen, D. The relationship among deficiency needs and growth needs: An empirical investigation of Maslow’s theory. Children and Youth Services Review 2012, 34, 1862–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, J.E.; Rindfleisch, A. Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer research 2002, 29, 348–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, J.N.; Hodge, A.S.; Zhang, H.; Van Tongeren, D.R.; Davis, D.E. Minimalism, voluntary simplicity, and well-being: A systematic review of the empirical literature. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2023, 18, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: The foundation of agency. Control of human behavior, mental processes, and consciousness: Essays in honor of the 60th birthday of August Flammer 2000, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Privette, G. Peak experience, peak performance, and flow: A comparative analysis of positive human experiences. Journal of personality and social psychology 1983, 45, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Kashdan, T.B. The unbearable lightness of meaning: Well-being and unstable meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2013, 8, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, J.; Park, M.S.A. “It’s Allowed Me to Be a Lot Kinder to Myself”: Exploration of the Self-Transformative Properties of Solitude During COVID-19 Lockdowns. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2023, p. 00221678231157796.

- Coplan, R.J.; Bowker, J.C.; Nelson, L.J. Alone again: Revisiting psychological perspectives on solitude. The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone 2021, pp. 1–15.

- Long, C.R.; Averill, J.R. Solitude: An exploration of benefits of being alone. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 2003, 33, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, A.J.; Schaefer, S.M. Affective Neuroscience of Loneliness: Potential Mechanisms underlying the Association between Perceived Social Isolation, Health, and Well-Being. Journal of psychiatry and brain science 2022, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor, S. The art of solitude; Yale University Press, 2020.

- Weinstein, N.; Vuorre, M.; Adams, M.; Nguyen, T.v. Balance between solitude and socializing: everyday solitude time both benefits and harms well-being. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 21160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafo, D. Alone Together: Solitude and the Creative Encounter in Art and Psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Dialogues - PSYCHOANAL DIALOGUES 2012, 22, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.B.; Gibson, H.B. The benefits of solitude. Loneliness in Later Life 2000, pp. 91–108.

- Naso, R.C. Immoral actions in otherwise moral individuals: Interrogating the structure and meaning of moral hypocrisy. Psychoanalytic psychology 2006, 23, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiman, C. Why be immoral? Ethical theory and moral practice 2010, 13, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gert, J. Michael Smith and the rationality of immoral action. The Journal of Ethics 2008, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, S. Violent video games and aggression: stimulation or catharsis or both? Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2021, 24, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.G.; Valenti, J.; Keil, F.C. Simplicity and complexity preferences in causal explanation: An opponent heuristic account. Cognitive psychology 2019, 113, 101222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive psychology 1973, 5, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.; Ayres, P. Cognitive load theory: A broader view on the role of memory in learning and education. Educational Psychology Review 2014, 26, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, C.R. Cognitive simplification processes in strategic decision-making. Strategic management journal 1984, 5, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsmeyer, C. Disgust and Aesthetics. Philosophy Compass 2012, 7, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohminger, N. The Hedonics of Disgust. 2013.

- Martin, G.N. (Why) Do You Like Scary Movies? A Review of the Empirical Research on Psychological Responses to Horror Films. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittrup, S. Why Do We Enjoy Scary Movies? Leviathan: Interdisciplinary Journal in English 2022, p. 11–30. [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.A.; Kanba, S.; Teo, A.R. Hikikomori: Multidimensional understanding, assessment, and future international perspectives. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2019, 73, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, A.R. A New Form of Social Withdrawal in Japan: a Review of Hikikomori. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2010, 56, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ángeles Malagón-Amor.; Córcoles-Martínez, D.; Martín-López, L.M.; Pérez-Solà, V. Hikikomori in Spain: A descriptive study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2015, 61, 475–483. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tateno, M.; Park, T.W.; Kato, T.; Umene-Nakano, W.; Saito, T. Hikikomori as a possible clinical term in psychiatry: A questionnaire survey. BMC psychiatry 2012, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, L.M.; Davis, E.P.; Luby, J.L.; Baram, T.Z.; Sandman, C.A. A predictable home environment may protect child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurobiology of Stress 2021, 14, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favre, M.R.; La Mendola, D.; Meystre, J.; Christodoulou, D.; Cochrane, M.J.; Markram, H.; Markram, K. Predictable enriched environment prevents development of hyper-emotionality in the VPA rat model of autism. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, S. The perils of obedience. Harper’s Magazine 1973, 247, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, S. Obedience without orders: Expanding social psychology’s conception of ‘obedience’. British Journal of Social Psychology 2019, 58, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrecque, F.; Potz, A.; Larouche, É.; Joyal, C.C. What is so appealing about being spanked, flogged, dominated, or restrained? Answers from practitioners of sexual masochism/submission. The Journal of Sex Research 2021, 58, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, H. Obedience. New Blackfriars 1984, 65, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, C.; Byers, E. Positive and Negative Cognitions of Sexual Submission: Relationship to Sexual Violence. Archives of sexual behavior 2006, 35, 483–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappeler, P.M.; Mass, V.; Port, M. Even adult sex ratios in lemurs: Potential costs and benefits of subordinate males in Verreaux’s sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi) in the Kirindy Forest CFPF, Madagascar. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2009, 140, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sincoff, J.B. The psychological characteristics of ambivalent people. Clinical psychology review 1990, 10, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.M.; Zanna, M.P. The conflicted individual: Personality-based and domain specific antecedents of ambivalent social attitudes. Journal of personality 1995, 63, 259–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfaillie, K. Punitive needs, society and public opinion: An explorative study of ambivalent attitudes to punishment and criminal justice. In Resisting Punitiveness in Europe?; Routledge, 2013; pp. 238–259.

- Gasper, K.; Middlewood, B.L. Approaching novel thoughts: Understanding why elation and boredom promote associative thought more than distress and relaxation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2014, 52, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, K.M.; Rietzschel, E.F.; Van Yperen, N.W. Stimulated by novelty? The role of psychological needs and perceived creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2018, 44, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Cutre, D.; Romero-Elías, M.; Jiménez-Loaisa, A.; Beltrán-Carrillo, V.J.; Hagger, M.S. Testing the need for novelty as a candidate need in basic psychological needs theory. Motivation and Emotion 2020, 44, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, L.; Milyavskaya, M. Novelty–variety as a candidate basic psychological need: New evidence across three studies. Motivation and Emotion 2020, 44, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, P. Confecting adventure and playing with meaning: The adventure commodification continuum. Journal of sport & tourism 2006, 11, 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Pomfret, G.; Sand, M.; May, C. Conceptualising the power of outdoor adventure activities for subjective well-being: A systematic literature review. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2023, 42, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell Jr, R.G.; et al. Mountain experience: The psychology and sociology of adventure. Mountain experience: the psychology and sociology of adventure. 1983.

- Geng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, C.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, S. Volunteering, charitable donation, and psychological well-being of college students in China. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 12, 790528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility: A consumer psychology perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology 2016, 10, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Scullion, H. The effect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on employee motivation: A cross-national study. Economics and Business Review 2013, 13, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorour, M.K.; Boadu, M.; Soobaroyen, T. The role of corporate social responsibility in organisational identity communication, co-creation and orientation. Journal of Business Ethics 2021, 173, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, R.I. Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Review of general psychology 2004, 8, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F. In praise of gossip: The organizational functions and practical applications of rumours in the workplace. Journal of Human Resources Management Research 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, B.; Khalsa, S.; Ecklund, E.H. Gossip as social control: Informal sanctions on ethical violations in scientific workplaces. Social Problems 2016, 63, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, J.B.; Subrin, M. The psychology of gossip. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 1963, 11, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, K.; Swargiary, K. Development and Guidance of Children; 2023.

- Hui, E.K. A guidance curriculum for student development: A qualitative study. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 2003, 25, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R. Guidance in the workplace. Taking Issue. Debates in Guidance and Counselling in Learning 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Krumboltz, J.D.; Becker-Haven, J.F.; Burnett, K.F. Counseling psychology. Annual Review of Psychology 1979, 30, 555–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suls, J.; Wheeler, L. Social comparison theory. Handbook of theories of social psychology 2012, 1, 460–482. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanowicz, J.C. The culture of mediocrity. Minerva 2013, 51, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F.; Smolak, L. Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention; Guilford press, 2011.

- Groesz, L.M.; Levine, M.P.; Murnen, S.K. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of eating disorders 2002, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. The elementary forms of religious life. In Social theory re-wired; Routledge, 2016; pp. 52–67.

- Tönnies, F. Studien zu Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft; Springer-Verlag, 2012.

- Davis, J.E. Identity and social change; Routledge, 2017.

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual review of sociology 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. science 1974, 185, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, C.G.; Ross, L.; Lepper, M.R. Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of personality and social psychology 1979, 37, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappin, B.M.; Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Rethinking the link between cognitive sophistication and politically motivated reasoning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 2021, 150, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunda, Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological bulletin 1990, 108, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, D.P. On contested concepts: humanitarianism, human rights, and the notion of neutrality. Journal of Human Rights 2013, 12, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringelheim, J. State Religious Neutrality as a Common European Standard? Reappraising the European Court of Human Rights Approach. Oxford Journal of Law and Religion 2017, 6, 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, K.T.; Riley, E.P. Beyond neutrality: The human–primate interface during the habituation process. International Journal of Primatology 2018, 39, 852–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzelman, S.J.; King, L.A. Routines and meaning in life. Personality and social psychology bulletin 2019, 45, 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatras, J.W.; Israel, A.C.; Sokolowski, K.L.; Ryan, J. First things first: Family activities and routines, time management and attention. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 2016, 47, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koome, F.; Hocking, C.; Sutton, D. Why routines matter: The nature and meaning of family routines in the context of adolescent mental illness. Journal of Occupational Science 2012, 19, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.B., Routine Matters: Narratives of Everyday Life in Families. In Social Conceptions of Time: Structure and Process in Work and Everyday Life; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, 2002; pp. 179–194. [CrossRef]

- Impett, E.A.; Javam, L.; Le, B.M.; ASYABI-ESHGHI, B.; Kogan, A. The joys of genuine giving: Approach and avoidance sacrifice motivation and authenticity. Personal Relationships 2013, 20, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Potegal, M. Appeasement and reconciliation: Introduction to an Aggressive Behavior special issue. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression 1997, 23, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Young, R.C.; Buswell, B.N. Appeasement in human emotion, social practice, and personality. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression 1997, 23, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.R. Transportation into a story increases empathy, prosocial behavior, and perceptual bias toward fearful expressions. Personality and individual differences 2012, 52, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Khalil, K.A.; Wharton, J. Empathy for animals: A review of the existing literature. Curator: The Museum Journal 2018, 61, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, R.A.; Oatley, K.; Hirsh, J.; Dela Paz, J.; Peterson, J.B. Bookworms versus nerds: Exposure to fiction versus non-fiction, divergent associations with social ability, and the simulation of fictional social worlds. Journal of research in personality 2006, 40, 694–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, P.E.; Brewer, W.F. Development of story liking: Character identification, suspense, and outcome resolution. Developmental Psychology 1984, 20, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R. Setting boundaries; Macmillan Publishers Aus., 2021.

- Rutherford, A.; Harmon, D.; Werfel, J.; Gard-Murray, A.S.; Bar-Yam, S.; Gros, A.; Xulvi-Brunet, R.; Bar-Yam, Y. Good fences: The importance of setting boundaries for peaceful coexistence. PloS one 2014, 9, e95660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Psychological detachment from work during leisure time: The benefits of mentally disengaging from work. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2012, 21, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Veer, P. The power of detachment: Disciplines of body and mind in the Ramanandi Order. American ethnologist 1989, 16, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottke, A. Setting Boundaries® with Your Aging Parents: Finding Balance Between Burnout and Respect; Harvest House Publishers, 2010.

- Imani, M.; Karimi, J.; Behbahani, M.; Omidi, A. Role of mindfulness, psychological flexibility and integrative self-knowledge on psychological well-being among the university students. Feyz Journal of Kashan University of Medical Sciences 2017, 21, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler, B. Self-knowledge; Routledge, 2010.

- Sharil, W.N.E.H.; Majid, F.A. Reflecting to Benefit: A Study on Trainee Teachers’ Self-Reflection. International Journal of Learning 2010, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, C.; Hayes, L.A. Self-efficacy and self-awareness: moral insights to increased leader effectiveness. Journal of Management Development 2016, 35, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.; Hussin, N.; Shonubi, O.A.; Ghazali, S.R.; Talib, M.A. Career decision-making competence, self-knowledge, and occupational exploration: a model for university students. Journal of Technical Education and Training 2018, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Legault, L. Need for Autonomy, The. In Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences; Springer, 2020; pp. 3118–3120.

- Tifferet, S.; Herstein, R. The effect of individualism on private brand perception: a cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2010, 27, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Nah, F.F.H.; Siau, K. An experimental study on ubiquitous commerce adoption: Impact of personalization and privacy concerns. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2008, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.Y.; Bodoff, D. The effects of Web personalization on user attitude and behavior. MIS quarterly 2014, 38, 497–A10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutmacher, F.; Appel, M. The Psychology of Personalization in Digital Environments: From Motivation to Well-Being–A Theoretical Integration. Review of General Psychology 2023, 27, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Escapism; JHU Press, 1998.

- Calleja, G. Digital games and escapism. Games and Culture 2010, 5, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.L. Theory of Spontaneity-Creativity. Sociometry 1955, 18, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, R.; Lemieux, A.F.; Chen, C. Spontaneity and creativity in highly practised performance. In Musical creativity; Psychology Press, 2006; pp. 216–234.

- Testoni, I.; Wieser, M.; Armenti, A.; Ronconi, L.; Guglielmin, M.; Cottone, P.; Zamperini, A. Spontaneity as predictive factor for well-being. Zeitschrift für Psychodrama und Soziometrie 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. Normal family processes; Guilford Press New York, 1982.

- Gapp, K.; Bohacek, J.; Grossmann, J.; Brunner, A.M.; Manuella, F.; Nanni, P.; Mansuy, I.M. Potential of environmental enrichment to prevent transgenerational effects of paternal trauma. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 2749–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).