Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

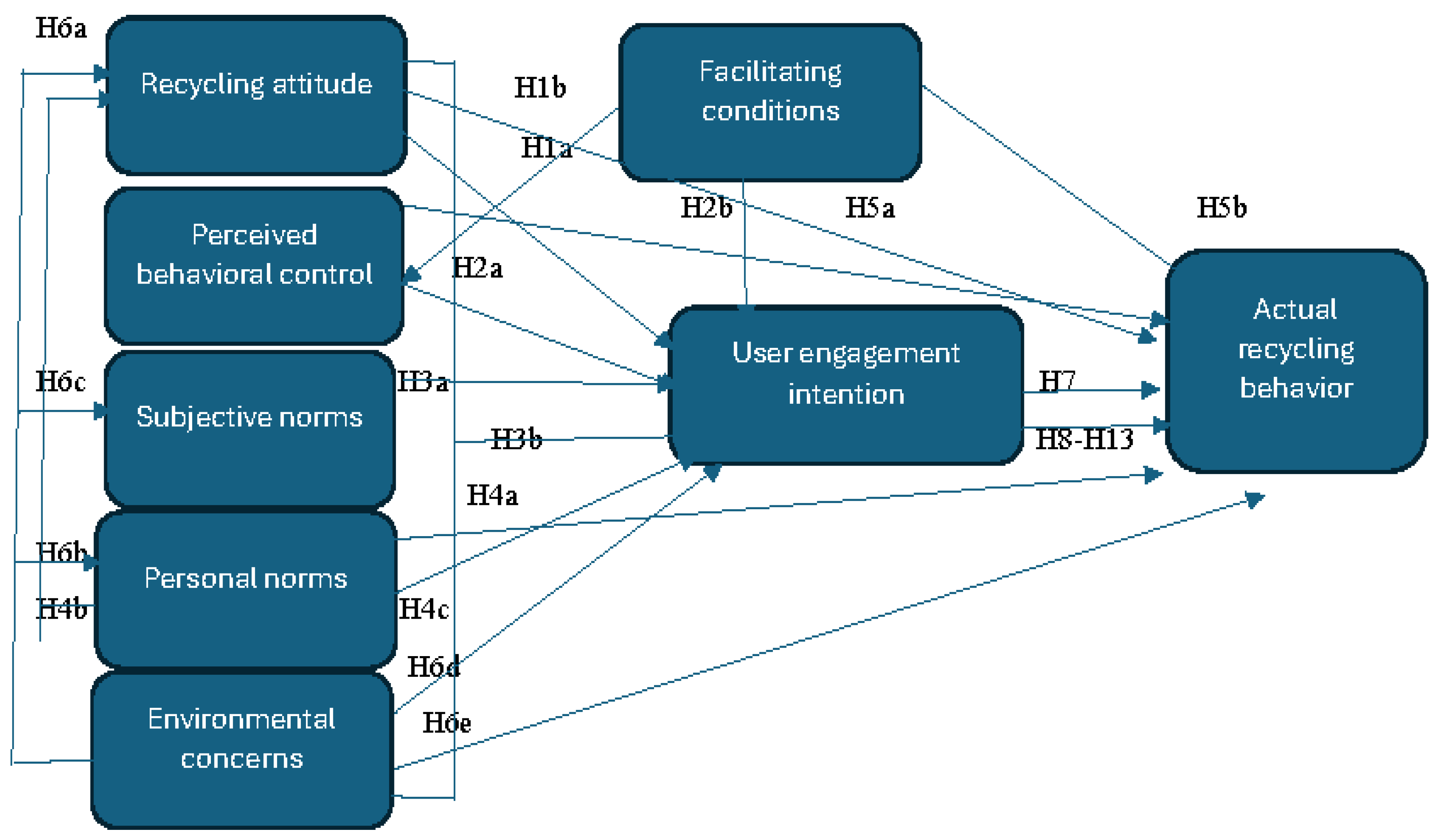

2.1. The Extended Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

2.2. Recycling Engagement

2.2.1. Recycling Attitude (RA) and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.2. Perceived Behavioral Control [PBC] and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.3. Subjective Norms [SN] and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.4. Personal Norms (PN) and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.5. Facilitating Conditions (FC) and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.6. Environmental Concerns (EC) and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.7. Recycling User Engagement and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Target Population

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

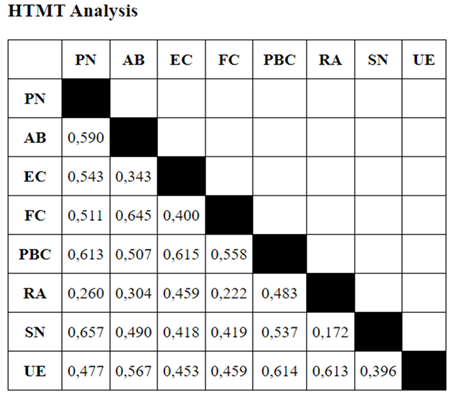

4.1. Validity and Reliability

| Construct | Item | Factor loadings | Cronbach’s alpha | Composite reliability | Average variance extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | RA 1 | 0.863 | 0.847 | 0.859 | 0.671 |

| RA 1 | 0.701 | ||||

| RA 1 | 0.788 | ||||

| PBC | PBC 1 | 0.782 | 0.835 | 0.842 | 0.576 |

| PBC 2 | 0.760 | ||||

| PBC 3 | 0.776 | ||||

| PBC 4 | 0.844 | ||||

| SN | SN 1 | 0.845 | 0.833 | 0.877 | 0.725 |

| SN 2 | 0.777 | ||||

| SN 3 | 0.873 | ||||

| PN | PN 1 | 0.797 | 0.825 | 0.829 | 0.619 |

| PN 2 | 0.695 | ||||

| PN 3 | 0.779 | ||||

| EC | EC 1 | 0.867 | 0.890 | 0.894 | 0.738 |

| EC 2 | 0.807 | ||||

| EC 3 | 0.856 | ||||

| FC | FC 1 | 0.810 | 0.876 | 0.835 | 0.630 |

| FC 2 | 0.657 | ||||

| FC 3 | 0.792 | ||||

| I | I 1 | 0.864 | 0.902 | 0.906 | 0.763 |

| I 2 | 0.827 | ||||

| I 3 | 0.885 | ||||

| ARB | ARB 1 | 0.600 | 0.758 | 0.770 | 0.532 |

| ARB 2 | 0.781 | ||||

| ARB 3 | 0.635 |

|

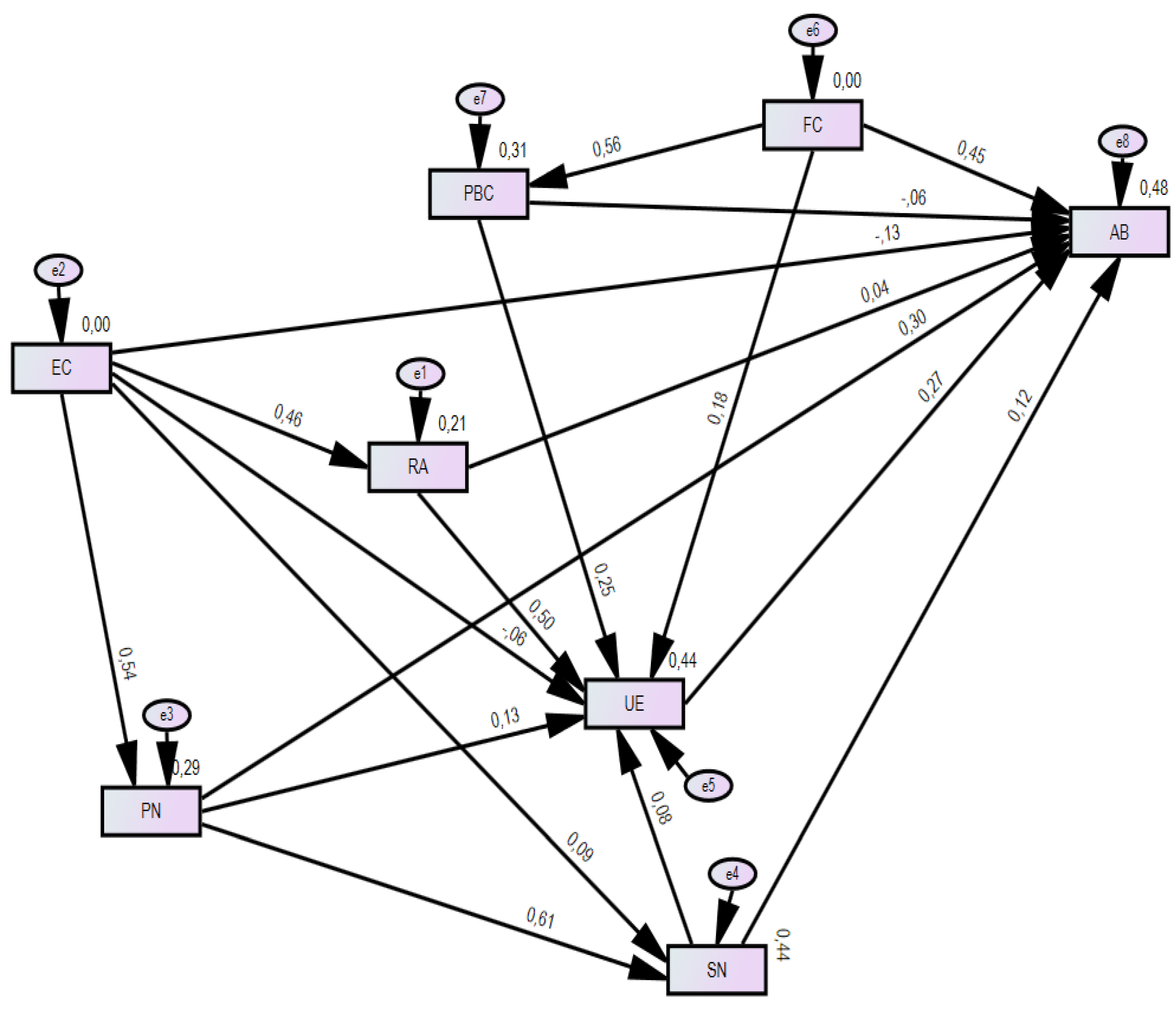

4.2. Hypothesis Testing: Direct Relationships

4.3. Hypotheses Testing: Indirect Relationships

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusion

6.1. Theoretical Recommendations

6.2. Practical Recommendations

6.3. Limitation and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thoo, A.C.; Tee, S.J.; Huam, H.T.; Mas’od, A. Determinants of recycling behavior in higher education institution. Social Responsibility Journal 2022, 18, 1660–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Marketing Association. People recycle more when they know what recyclable waste becomes. 2019. Available online: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/05/190516103712.htm [accessed 3 December 2024].

- Department of Environmental Affairs. State of Waste Report South Africa. 2018. Available online: http://sawic.environment.gov.za/?menu=346 [accessed 30 August 2024].

- Xia, Z.; Gu, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Liu, F.; Wen, X.; Tian, X.; Zhang, C. Do behavioral interventions enhance waste recycling practices? Evidence from an extended meta-analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 385, 135695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, W. Applying the theory of planned behavior to recycling behavior in South Africa. Recycling 2018, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotto, A.; Spagnolli, A. Psychological strategies to promote household recycling: a systematic review with meta-analysis of validated field interventions. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2017, 51, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froestad, J. Environmental health problems in Hout Bay: The challenge of generalising trust in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 2005, 31, 333–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.K.; Yongsheng, Z.; Jun, D. Municipal solid waste management challenges in developing countries: Kenyan case study. Waste Management 2006, 26, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, B.; Hansen, I.L.; Oosthuizen, M. Experiences with and the viability of a recycling pilot project in a Cape Town township. Development Southern Africa 2019, 36, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.E. Attitudes and practices of households toward waste management and recycling in Nelson Mandela Bay. Journal of Contemporary Management 2020, 17, 573–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, C. Assessment of barriers preventing recycling practices among bars and eateries in central South Africa. Dissertation, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kamleitner, B.; Thürridl, C.; Martin, B.A. Cinderella story: How past identity salience boosts demand for repurposed products. Journal of Marketing 2019, 83, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishami, S.; Shirali, A.; Sharples, N.; Kartal, G.E.; Macintyre, L.; Doustdar, O. Textile Recycling and Recovery: An eco-friendly perspective on textile and garment industries challenges. Textile Research Journal 2024, 94, 2815–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Asamoah, A.N.; Nketiah, E.; Obuobi, B.; Adjei, M.; Cudjoe, D.; Zhu, B. Reducing waste management challenges: empirical assessment of waste sorting intention among corporate employees in Ghana. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2023, 72, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, N.; Lada, S.; Chekima, B.; Abdul Adis, A.A. Exploring determinants shaping recycling behavior using an extended theory of planned behavior model: An empirical study of households in Sabah, Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. A Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergura, D.T.; Zerbini, C.; Luceri, B.; Palladino, R. Investigating sustainable consumption behaviors: a bibliometric analysis. British Food Journal 2023, 125, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, A.; Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O. Towards a circular economy: Implications for emission reduction and environmental sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 2023, 32, 1951–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Nenkov, G.Y.; Gonzales, G.E. Knowing what it makes: How product transformation salience increases recycling. Journal of Marketing 2019, 83, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Addar, W.; Orghemmi, C.; Takaffoli, M. Overview of factors influencing consumer engagement with plastic recycling. WIREs Energy Environ 2023, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, B.T.; Mollenkopf, D.A.; Wang, Y. Remanufacturing for the circular economy: An examination of consumer switching behavior. Business Strategy and the Environment 2017, 26, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunka, A.D.; Linder, M.; Habibi, S. Determinants of consumer demand for circular economy products. A case for reuse and remanufacturing for sustainable development. Business Strategy and the Environment 2021, 30, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.L.; Hopkinson, P.G.; Tidridge, G. Val creation from circular economy-led closed loop supply chains: A case study of fast-moving consumer goods. Production Planning and Control: The Management of Operations 2018, 29, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Badejo, A.; Carlini, J.; France, C.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Knox, K.; Pentecost, R.; Perkins, H.; Thaichon, P.; Sarker, T.; Wright, O. Predicting intention to recycle on the basis of the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 2019, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vilkaite-Vaitone, N.; Jeseviciute-Ufartiene, L. Predicting textile recycling through the lens of the theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiyane, E.; Schoeman, T. Recycling Behavior of Students at a Tertiary Institution in South Africa. 18th Johannesburg International Conference on Science, Engineering, Technology & Waste Management (SETWM-20), Johannesburg, South Africa, Nov. 16-17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Danson, G.; Hancocks, J. Attitude and practices of consumers towards recycling of household waste in Mandela. Bay. Dissertation, Nelson Mandela University, Gqeberha, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pewa, M.K.P. Household waste management in a South African township. Thesis, University of Hull, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schwan, A. Recycling: Why do South Africans care so little about it. 2023. Available online at: https://www.thesouthafrican.com/news/www-thesouthafrican-news-recycling-is-not-on-our-minds-03-may-2023/ [accessed 4 February 2024].

- Haywood, L.K.; Kapwata, T.; Oelofse, S.; Breetzke, G.; Wright, C.Y. Waste Disposal Practices in Low-Income Settlements of South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polasi, T.; Matinise, S.; Oelofse, S. South African municipal waste management systems: challenges and solutions. The International Environmental Technology Centre (IETC). 2020. Available online at: file:///C:/Users/makhikm/Downloads/SAM%20(3).pdf [accessed 24 February 2024].

- Erst, M.; Addar, W.; Orghemmi, C.; TakaffoliTakaffoli, M. Overview of factors influencing consumer engagement with plastic recycling. WIREs Energy Environment 2023, 12, e493. [Google Scholar]

- Helmefalk, M.; Palmquist, A.; Rosenlund, J. Understanding the mechanisms of household and stakeholder engagement in a recycling ecosystem: The SDL perspective. Waste Management 2023, 160, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, P. Cities of Gold, Townships of Coal: Essays on South Africa's New Urban Crisis; Africa World Press: Trenton, New Jersey, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens, U.; Donaldson, R.; Rule, J.; Bäh, J. Townships in South African cities: Literature review and research perspectives. Habitat International 2013, 39, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, T.; Barnes, J.M.; Pieper, C.H. Contribution of water pollution from inadequate sanitation and housing quality to diarrheal disease in low-cost housing settlements of Cape Town, South Africa. American Journal of Public Health 2011, 101, e4–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M. Campus sustainability: An integrated model of college students’ recycling behavior on campus. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2019, 20, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Liu, P. Exploring waste separation using an extended theory of planned behavior: A comparison between adults and children. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15, 1337969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Mai, L.H.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Nguyen, T.M.L.; Nguyen, T.P.L. The factors affecting Vietnamese people’s sustainable tourism intention: an empirical study with extended the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Foresight Journal 2023, 25, 844–860.aly. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.; Galati, A.; Schifani, G.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Migliore, G. Culinary tourism experiences in agri-tourism destinations and sustainable consumption: understanding Italian tourists’ motivations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Meng, B.; Kim, W. Emerging bicycle tourism and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2016, 25, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Ye, J. Determinants of consumers’ apparel recycling behavior intention using the extended norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior: an empirical study from China. Environment, Developent & Sustainability 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Qin, S.; Gou, Z.; Yi, M. Can green building promote pro-environmental behaviors? The psychological model and design strategy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; McDonald, S.; Korobilis-Magas, E.; Osobajo, O.A.; Awuzie, B.O. Reframing recycling behavior through consumers’ perceptions: An exploratory investigation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Business Research 2023, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; Tang, W. Virtual brand community engagement practices: a refined typology and model. Journal of Services Marketing 2017, 31, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, C.R.; Kaikati, A.M. Consumers’ use of brands to reflect their actual and ideal selves on Facebook. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2012, 29, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langaro, D.; Rita, P.; Salgiro, M. Do social networking sites contribute for building brands? Evaluating the impact of users' participation on brand awareness and brand attitude. Journal of Marketing Communications 2018, 24, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L. Social media engagement: a model of antecedents and relational outcomes. Journal of Marketing Management 2017, 33, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Bairrada, C.; Peres, F. Brand communities’ relational outcomes, through brand love. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2019, 28, 154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Baldus, B.J.; Voorhees, C.; Calantone, R. Online brand community engagement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research 2019, 68, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: a social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2015, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, B.J.; Malthouse, E.C.; Schaedel, U. An experimental study of the relationship between online engagement and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2009, 23, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenraam, A.W.; Eelen, J.; van Lin, A.; Verlegh, P.W.J. A consumer-based taxonomy of digital customer engagement practices. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2018, 44, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Juri´c, B.; Ili´C, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E.; Alexander, M. Role of customer engagement behavior in val co-creation: a service system perspective. Journal of Service Research 17, 247–261. [CrossRef]

- Knickmeyer, D. Social factors influencing household waste separation: A literature review on good practices to improve the recycling performance of urban areas. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 245, 118605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldero, J. The prediction of household recycling of newspapers: The role of attitudes, intentions, and situational factors. Journal of Applied Soc. Psychology 1995, 25, 440–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Habibi, M.R.; Richard, M. To be or not to be in social media: How brand loyalty is affected by social media? International Journal of Information Management 2013, 33, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Guan, Y. A joint use of energy evaluation, carbon footprint and economic analysis for sustainability assessment of grain system in China during 2000–2015. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2018, 17, 2822–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Tan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Tao, Y.; Qian, Y. Investigation on decision-making mechanism of residents’ household solid waste classification and recycling behaviors. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2019, 140, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Yang, W.; Shen, X. A comparison study of ‘motivation–intention–behavior’ model on household solid waste sorting in China and Singapore. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 211, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gozet, B. Food waste matters: A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 182, 978e991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, A.; Sciandra, M.R.; Inman, J. The effects of content characteristics on consumer engagement with branded social media content on Facebook. Marketing Science Institute Working Paper Series, Report No. 15-110. 2015.

- Woodard, R.; Rossouw, A. Increasing recycling through effective resident engagement at multiple occupancy housing developments: The waste its mine its your project. ISWA 2015 World Congress Antwerp; 2015; pp. 450–460. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassan, H.; Kwakwa, P.A.; Owusu-Sekyere, E. Households’ source separation behavior and solid waste disposal options in Ghana’s Millennium City. Journal of Environ. Management 2020, 259, 110055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Ahmad, A.; Madsen, D.Ø.; Sohail, S.S. Sustainable behavior with respect to managing e-wastes: factors influencing e-waste management among young consumers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstad, S.P.; Tobolova, M.; Nayum, A.; Klöckner, C.A. Understanding the mechanisms behind changing people’s recycling behavior at work by applying a comprehensive action determination model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.R.; Nielsen, J.M. Recycling as altruistic behavior: Normative and behavioral strategies to expand participation in a community recycling program. Environment and Behavior 1991, 23, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, F.; Daud, D.; Weng-Wai, C.; Jiram, W.R.A. Waste separation at source behavior among Malaysian households: the theory of planned behavior with moral norm. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 271, 122025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbir, M.; Raziuddin Taufiq, R.; Nomi, M. Consumers’ reverse exchange behavior and e-waste recycling to promote sustainable post-consumption behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2023, 35, 2484–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Zeidi, I.M.; Emamjomeh, M.M.; Asefzadeh, S.; Pearson, H. Household waste behaviors among a community sample in Iran: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Waste Management 2014, 34, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.; Bishop, B.A. Moral basis for recycling: extending the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2013, 36, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Cheung, R.; Shen, G.Q. Recycling attitude and behavior in university campus: a case study in Hong Kong. Facilities 2012, 30, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Ge, J. What affects consumers’ intention to recycle retired EV batteries in China? Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 359, 132065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Exploring young adults’ e-waste recycling behavior using an extended theory of planned behavior model: a cross-cultural study. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2019, 141, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A. Understanding consumers’ behavior intentions towards dealing with the plastic waste: perspective of a developing country. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 142, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A. Antecedents to green buying behavior: a study on consumers in an emerging economy. Mark. Intell. Plan 2015, 33, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmentally friendly activities. Tour Manag 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-T.; Huang, M.-H.; Cheng, B.-Y.; Chiu, R.-J.; Chiang, Y.-T.; Hsu, C.-W.; Ng, E. Applying a comprehensive action determination model to examine the recycling behavior of Taipei city residents. Sustainability 2021, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamrezai, S.; Aliabadi, V.; Ataei, P. Understanding the pro-environmental behavior among green poultry farmers: application of behavioral theories. Environ. Dev. Sustain 2021, 23, 16100–16118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S. Information publicity and resident’s waste separation behavior: an empirical study based on the norm activation model. Waste Management 2019, 87, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Moser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: a new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. Journal of Consumer Market 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D. Predicting household PM2.5-reduction behavior in Chinese urban areas: an integrative model of theory of planned behavior and norm activation theory. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 145, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.F.; Malesios, C. Extending the theory of planned behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Cai, L.; Yn, K.F.; Wang, X. Exploring consumers’ usage intention of reusable express packaging: An extended norm activation model. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2023, 72, 103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhan, W. How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. Journal Cleaner Production 2018, 172, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. One model to predict them all: predicting energy behaviors with the norm activation model. Energy Res. Social Sci. 2015, 6, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.; Lally, P.; Rebar, A.L. Does habit weaken the relationship between intention and behavior? Revisiting the habit-intention interaction hypothesis. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2020, 14, e12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.-Y.; Rahim, M.A. Socio-behavioral study of home computer users’ intention to practice security. 2005, pp. 234–247. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1132&context=pacis2005 [accessed 10 November 2024].

- Ibrahim, A.; Knox, K.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Arli, D. Segmenting a water use market: theory of interpersonal behavior insights. Social Marketing Quarterly 2018, 24, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Huang, R.; Jo, M.S.; Karakas, F.; Sarig¨ollü, E. From single use to multi-use: study of consumers’ behavior toward consumption of reusable containers. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 193, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J. Triandis’ Theory of Interpersonal Behavior in understanding software piracy behavior in the South African context. Master’s thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, WIReDSpace. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, N.; Rosenthal, S.; Sörqvist, P.; Barthel, S. Internal and external factors' influence on recycling: Insights from a laboratory experiment with observed behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 699410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bervell, B.; Kumar, J.A.; Arkorful, V.; Agyapong, E.M.; Osman, S. Remodelling the role of facilitating conditions for Google Classroom acceptance: A revision of UTAUT2. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2021, 38, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.S.; Abdullah, S.H.; Abd Manaf, L.; Sharaai, A.H.; Nabegu, A.B. Examining the moderating role of perceived lack of facilitating conditions on household recycling intention in Kano, Nigeria. Recycling 2024, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, R.; Sarabhai, S. Extrinsic motivators driving adults purchase intention on mobile apps: The mediating role of self-efficacy and facilitating conditions. Journal of Marketing Communications 2024, online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Y-k Kim, S.; Kim, M.-s.; Choi, J.-g. Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Business Research 2014, 67, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.; Jones, R. Environmental Concern: Conceptual and Measurement Isss. In Handbook of environmental sociology; Dunlap, R., Michelson, W., Eds.; Greenwood: London, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. Journal of Business Research 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D.; Yang, S.; Fu, Y. Predicting consumers’ intention to adopt hybrid electric vehicles: using an extended version of the theory of planned behavior model. Transportation 2016, 43, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklic, M.K.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Zabkar, V. The interplay of past consumption, attitudes and personal norms in organic food buying. Appetite 2019, 137, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotyza, P.; Cabelkova, I.; Pierański, B.; Malec, K.; Borusiak, B.; Smutka, L.; Nagy, S.; Gawel, A.; Bernardo López Lluch, D.; Kis, K.; Gál, J.; Gálová, J.; Mravcová, A.; Knezevic, B.; Hlaváček, M. The predictive power of environmental concern perceived behavioral control and social norms in shaping pro-environmental intentions: a multicountry study. Front. Ecol. Evol 2024, 12, 1289139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusiak, B.; Szymkowiak, A.; Horska, E.; Raszka, N.; Żelichowska, E. Towards building sustainable consumption: A study of second-hand buying intentions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M. Effects of environmental concerns and green knowledge on green product consumptions with an emphasis on mediating role of perceived behavioral control, perceived val, attitude, and subjective norm. International Transaction Journal of Engineering, Management, and Applied Sciences & Technologies 2019, 10, 651–661. [Google Scholar]

- Cilliers, J.O. High inventory levels: The raison d’être of township retailers. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 2018, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, M.V. Perceptions of informal local traders on the influence of emerging markets: Umlazi and Kwa-Mashu townships. Master’s dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmeni, Z.Z.; Madyira, D.M. A review of the current municipal solid waste management practices in Johannesburg City townships. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 35, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, A.A.; Shakantu, W. The health and environmental impact of plastic waste disposal in South African townships: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A. The robustness of maximum likelihood estimation in structural equation models. In Structural modelling by example; Cuttance, P., Ecob, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 1987; pp. 160–188. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.A. Study on millennial purchase intention of green products in India: Applying extended theory of planned behavior model. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business 2019, 20, 322–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The recycling of solid wastes: Personal vals, val orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhai, J. Understanding waste management behavior among university students in China: Environmental knowledge, personal norms, and the theory of planned behavior. Frontier Psychology 2022, 12, 771723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbelstein, T.; Lochner, C. Factors influencing purchase intention for recycled products: A comparative analysis of Germany and South Africa. Sustainable Development 2023, 31, 2256–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriyadi, S.B.; Puspitasari, R. Consumer intentions to reduce food waste in all-you-can-eat restaurants based on personal norm activation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Lee, J. Household waste separation intention and the importance of public policy. International Trade, Politics and Development 2020, 4, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Theory of Planned Behavior Approach to Understand the Purchasing Behavior for Environmentally Sustainable Products. Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad-380 015, W.P. No. 2012-12-08. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling; Guilford Press: New York, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th edition.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing research: An applied orientation, 7th edition; Pearson Education: England, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufiq, K.M.R.; Vaithianathan, S.A. A fresh look at understanding green consumer behavior among young urban indian consumers through the lens of theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 183, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Tarafder, T.; Pearson, D.; Henryks, J. Intention-behavior gap and perceived behavioral control-behavior gap in theory of planned behavior: moderating roles of communication, satisfaction and trust in organic food consumption. Food Quality and Preference 2020, 81, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Badgaiyan, A.J. Towards improved understanding of reverse logistics -examining mediating role of return intention. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2016, 107, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .Largo-Wight, E.; Bian, H.; Lange, L. An empirical test of an expanded version of the theory of planned behavior in predicting recycling behavior on campus. American Journal of Health Education 2012, 43, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Val | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 275 | 66,9% |

| Female | 136 | 33,1% | |

| Total | 411 | 100,0% | |

| Age | 18–24 years | 116 | 28,2% |

| 25–29 years | 111 | 27,0% | |

| 30–40 years | 145 | 35,3% | |

| 41–50 years | 28 | 6,8% | |

| 51-59 | 7 | 1,7% | |

| 60+ | 4 | 1,0% | |

| Total | 411 | 100,0% | |

| Marital status | Married | 96 | 23,4% |

| Unmarried | 315 | 76,6% | |

| Total | 411 | 100,0% | |

| Level of education | Did not complete high school | 11 | 2,7% |

| Completed Grade 12/matric | 154 | 37,5% | |

| Completed short courses | 25 | 6,1% | |

| Post-school qualification – diploma or certificate | 119 | 29,0% | |

| Post-school qualification – degree | 102 | 24,8% | |

| Total | 411 | 100,0% | |

| Income | R0 - R2,500 [$132] | 103 | 25,1% |

| R2,501 [$132] - R5,000 [$264] | 69 | 16,8% | |

| R5,001 [$264] - R7,500 [$397] | 68 | 16,5% | |

| R7,501 [397] - R12,500 [$661] | 64 | 15,6% | |

| R12,501 [$661] - R20,000 [$1058] | 65 | 15,8% | |

| More than R20,000 [$1058] | 42 | 10,2% | |

| Total | 411 | 100,0% |

| Indices | CMIN | df | CMIN/df | GFI | NFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Val(UE)s | 509.49 | 247 | 2.063 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.051 | 0.046 |

| Hypotheses | Standard beta coefficient | S.E. | t-values | p-values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | 0.499 | 0.073 | 6.836 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H1b | 0,177 | 0.073 | 2.565 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H2a | 0.253 | 0.080 | 3.163 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H2b | 0.004 | 0.080 | 0.044 | 0.986 | Rejected |

| H3a | 0.076 | 0.052 | 1.462 | 0.143 | Rejected |

| H3b | 0.142 | 0.057 | 2.491 | 0.013 | Supported |

| H4a | 0.181 | 0.060 | 3.017 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H4b | 0.609 | 0.050 | 12.180 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H4c | 0.421 | 0.060 | 6.379 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5a | 0.318 | 0.066 | 4.818 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H5b | 0.496 | 0.066 | 7.515 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H5c | 0.557 | 0.045 | 12.378 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6a | 0.462 | 0.067 | 6.896 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6b | 0.542 | 0.050 | 10.840 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6c | 0.418 | 0.058 | 7.207 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6d | 0.278 | 0.088 | 3.159 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6e | 0.115 | 0.063 | 1.825 | 0.056 | Supported |

| H7 | 0.274 | 0.068 | 4.029 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Path | Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect | S.E. | t-val | p-val | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H8: RA → I → AB | 0.203 | 0.047 | 0.156 | 0.049 | 3.184 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H9: PBC → I → AB | 0.005 | -0.073 | 0.078 | 0.030 | 2.600 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H10: SN → I → AB | 0.119 | 0.102 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 1.385 | 0.104 | Rejected |

| H11: PN → I → AB | 0.382 | 0.270 | 0.033 | 0.017 | 1.941 | 0.007 | Supported |

| H12: FC → I → AB | 0.434 | 0.390 | 0.042 | 0.018 | 2.333 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H13: EC → I → AB | 0.185 | -0.133 | -0.016 | 0.022 | -0.727 | 0.364 | Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).