Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model

2.2. Molecular Dynamics

2.3. Force Calculations

2.4. Methods of Investigation

3. Results

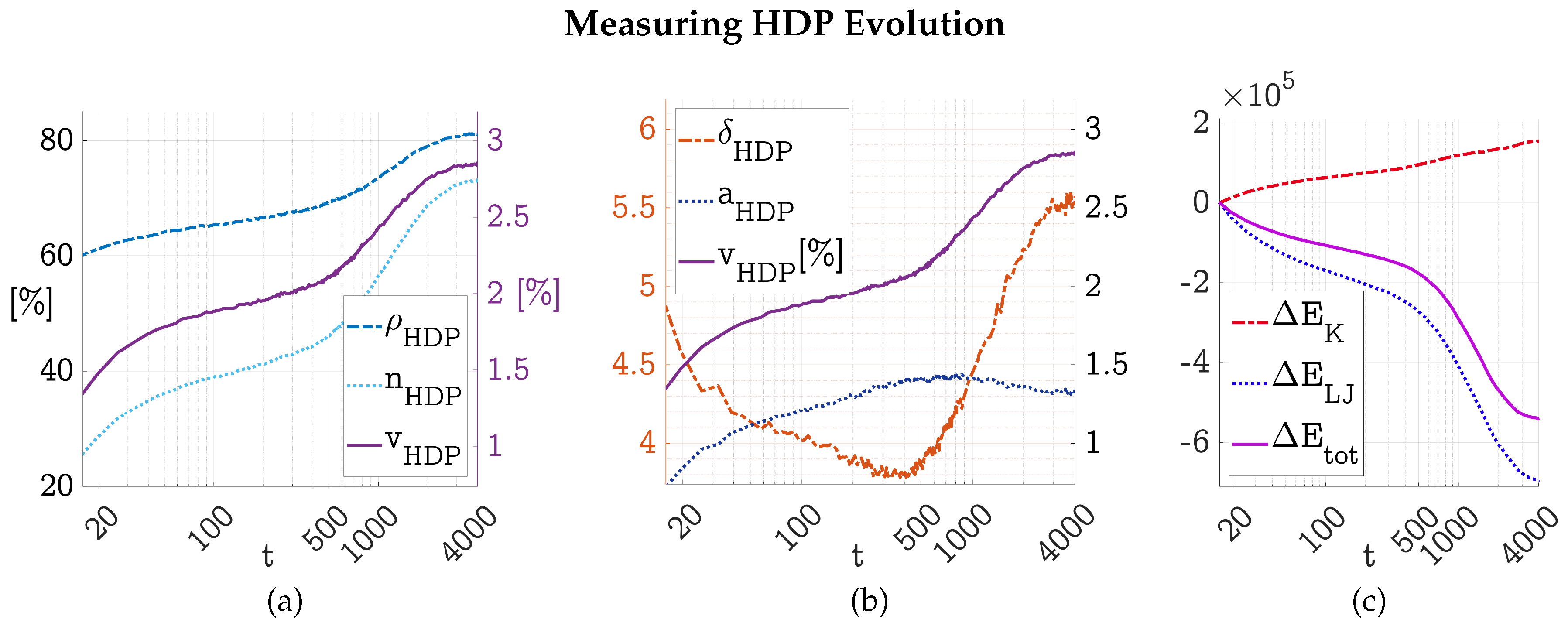

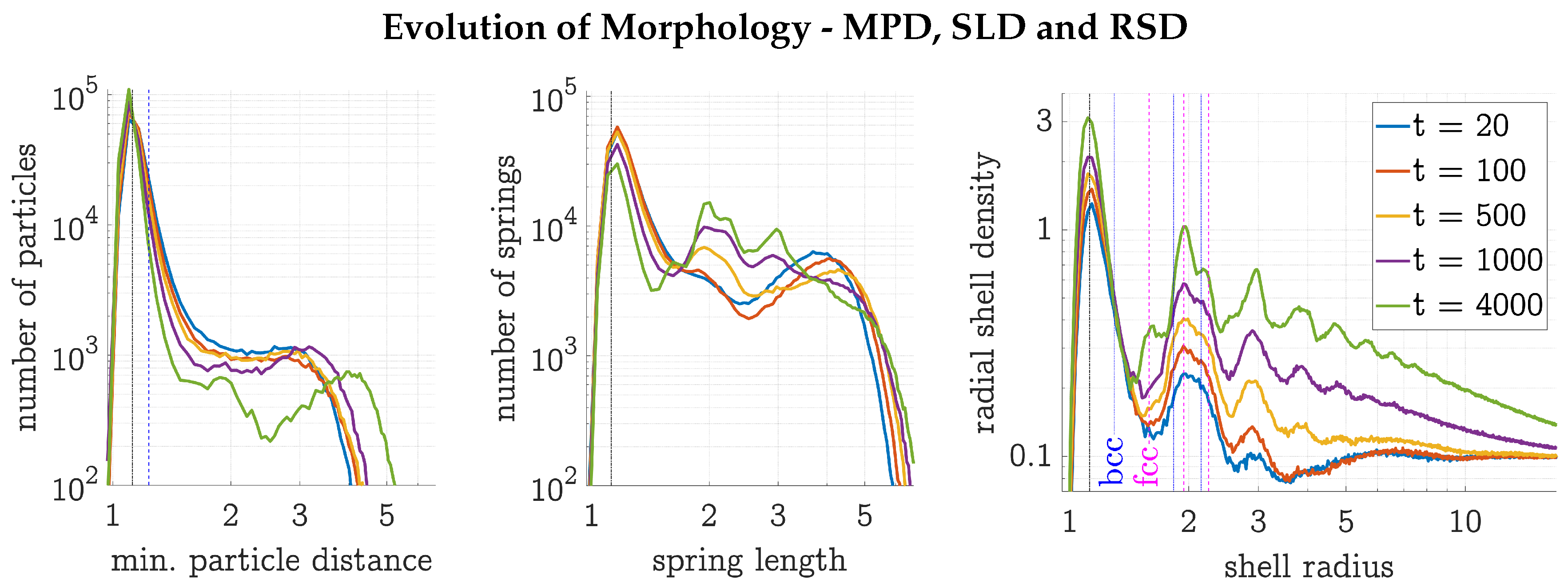

3.1. Evolution of a HDP Network

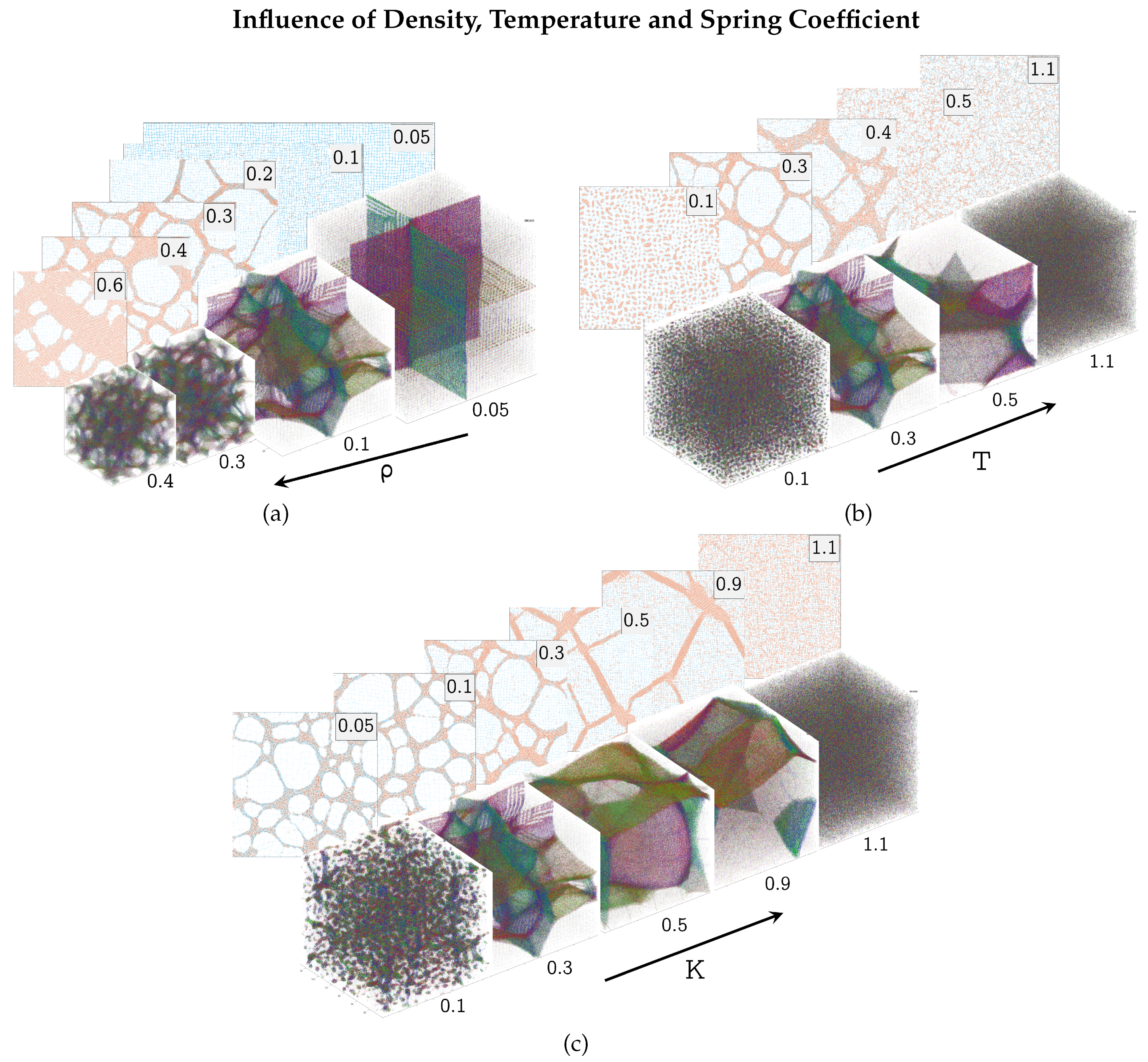

3.2. Parameter Variations

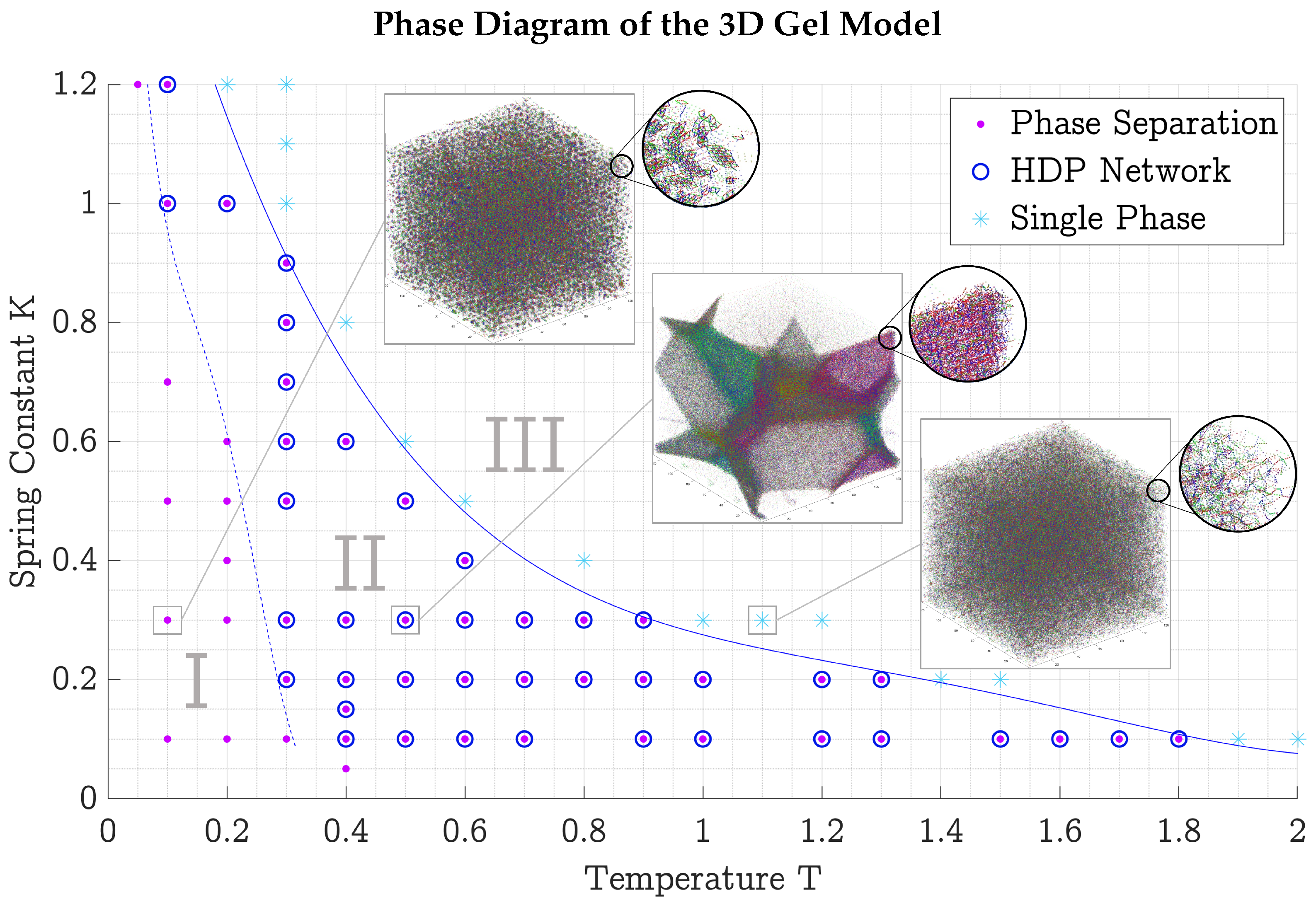

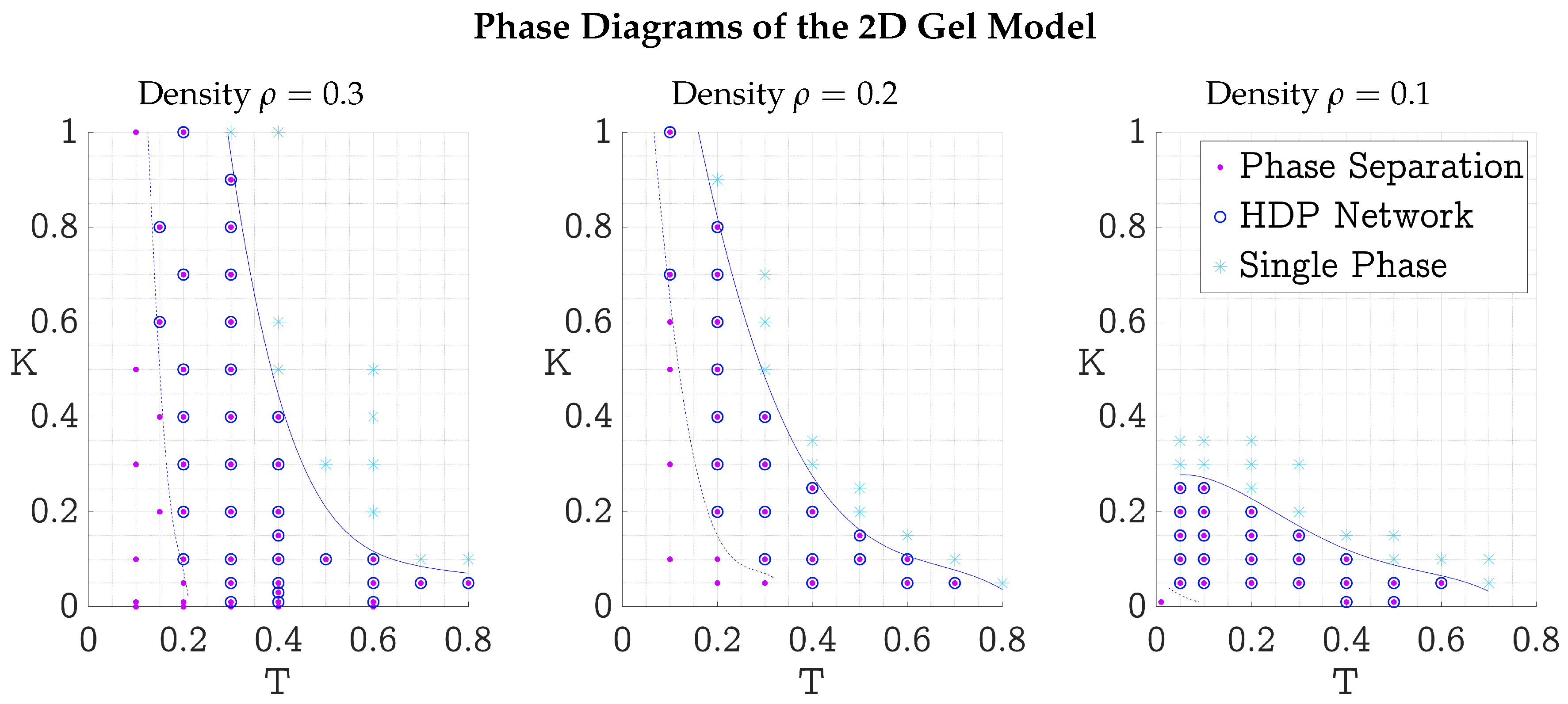

3.3. Phase Diagrams

4. Discussion

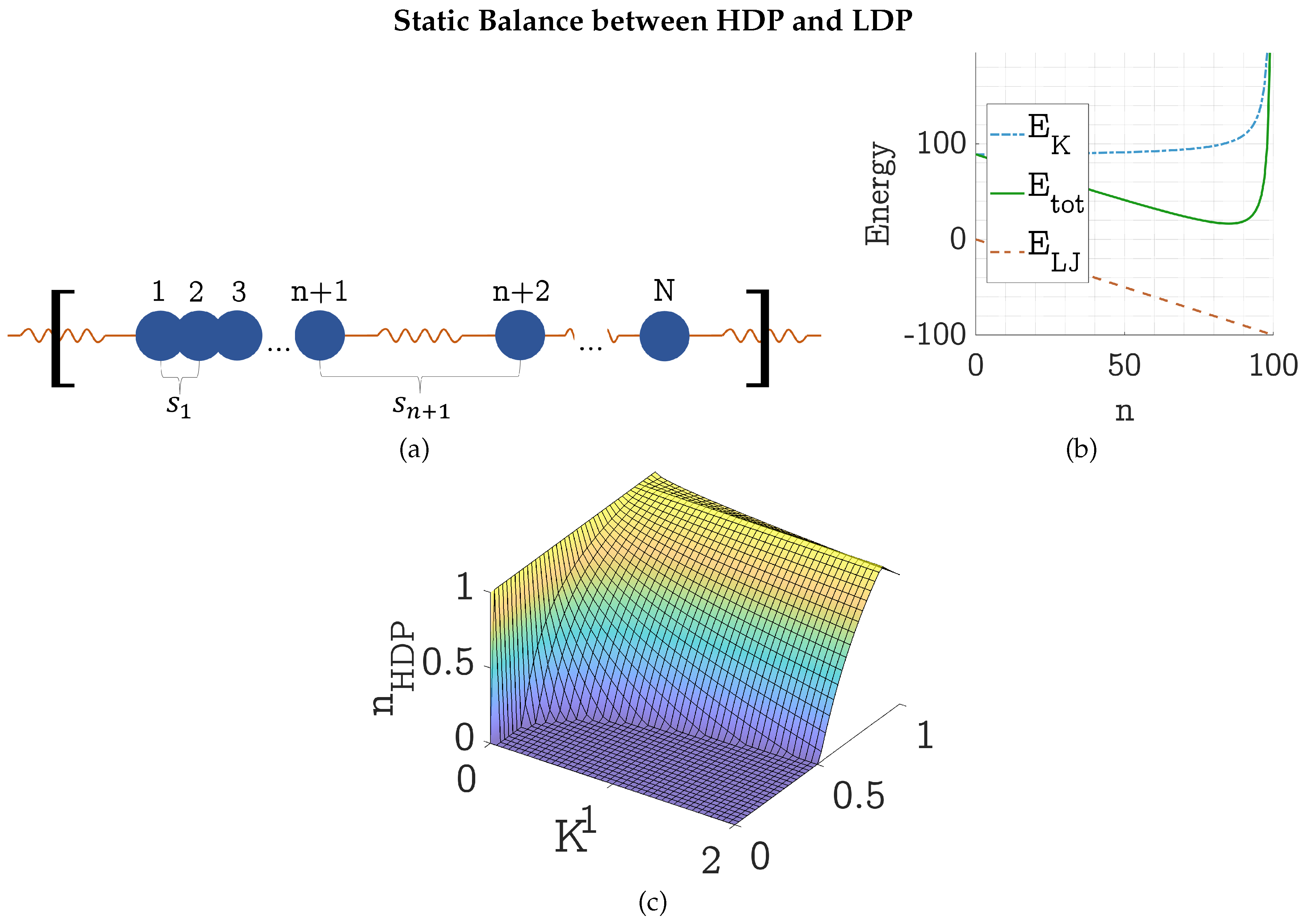

4.1. Static Energy Balance between HDP and LDP

4.2. Formation and Dissolution of HDP

4.3. Future Works

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Peleg, O.; Kröger, M.; Hecht, I.; Rabin, Y. Filamentous networks in phase-separating two-dimensional gels. Europhys. Lett. (EPL) 2007, 77, 58007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O.; Kröger, M.; Rabin, Y. Model of Microphase Separation in Two-Dimensional Gels. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 3267–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Tirado, M.; Castro, L.; Guéguen, A.; Mecerreyes, D. Iongel Soft Solid Electrolytes Based on [DEME][TFSI] Ionic Liquid for Low Polarization Lithium-O2 Batteries. Batteries & Supercaps, p. e202200049. Available online: https://chemistry-europe.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/batt.202200049. [CrossRef]

- Chotsuwan, C.; Boonrungsiman, S.; Chokanarojwong, T.; Dongbang, S. Mesoporous soft solid electrolyte-based quaternary ammonium salt. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2017, 21, 3011–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, K.; Liu, L.; Sharma, P. Theory of soft solid electrolytes: Overall properties of composite electrolytes, effect of deformation and microstructural design for enhanced ionic conductivity. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 2022, 158, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.L.; Yin, Z.N. Finite Inelastic Deformations of Compressible Soft Solids with the Mullins Effect. In Advanced Methods of Continuum Mechanics for Materials and Structures; Naumenko, K., Aßmus, M., Eds.; Springer, Singapore: Singapore, 2016; pp. 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekimoto, K.; Suematsu, N.; Kawasaki, K. Spongelike domain structure in a two-dimensional model gel undergoing volume-phase transition. Phys. Rev. A 1989, 39, 4912–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peleg, O.; Kröger, M.; Rabin, Y. Effect of network topology on phase separation in two-dimensional Lennard-Jones networks. Phys. Rev. E 2009, 79, 040401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.P.; Aktulga, H.M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D.S.; Brown, W.M.; Crozier, P.S.; in ’t Veld, P.J.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S.G.; Nguyen, T.D.; et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Comm. 2022, 271, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, A.J.; Kofke, D.A. Comprehensive high-precision high-accuracy equation of state and coexistence properties for classical Lennard-Jones crystals and low-temperature fluid phases. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2018, 149, 204508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, S.; Staubach, J.; Hasse, H. Review and comparison of equations of state for the Lennard-Jones fluid. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2020, 523, 112772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezanson, J.; Edelman, A.; Karpinski, S.; Shah, V.B. Julia: A fresh approach to numerical computing. SIAM review 2017, 59, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinet, G.; Searby, G.; Stauffer, D. Fire propagation in a 2-D random medium. Journal De Physique 1986, 47, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, D.; Aharony, A. Introduction To Percolation Theory: Second Edition; Taylor & Francis, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Fransson, S.; Peleg, O.; Lorén, N.; Kröger, A.H.M. Modeling and confocal microscopy of biopolymer mixtures in confined geometries. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 2713–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaberova, Z.; Karpushkin, E.; Nevoralová, M.; Vetrík, M.; Šlouf, M.; Dušková-Smrčková, M. Microscopic Structure of Swollen Hydrogels by Scanning Electron and Light Microscopies: Artifacts and Reality. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagmann, K.; Bunk, C.; Böhme, F.; von Klitzing, R. Amphiphilic Polymer Conetwork Gel Films Based on Tetra-Poly(ethylene Glycol) and Tetra-Poly(ϵ-Caprolactone). Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damaschin, R.P.; Lazar, M.M.; Ghiorghita, C.A.; Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Volf, I.; Dinu, M.V. Stabilization of Picea abies Spruce Bark Extracts within Ice-Templated Porous Dextran Hydrogels. Polymers 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimic-Misic, K.; Imani, M.; Gasik, M. Effects of Hydroxyapatite Additions on Alginate Gelation Kinetics During Cross-Linking. Polymers 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cengiz, I.F.; Oliveira, J.M.; Reis, R.L. Micro-CT – a digital 3D microstructural voyage into scaffolds: a systematic review of the reported methods and results. Biomaterials Research 2018, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).