Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

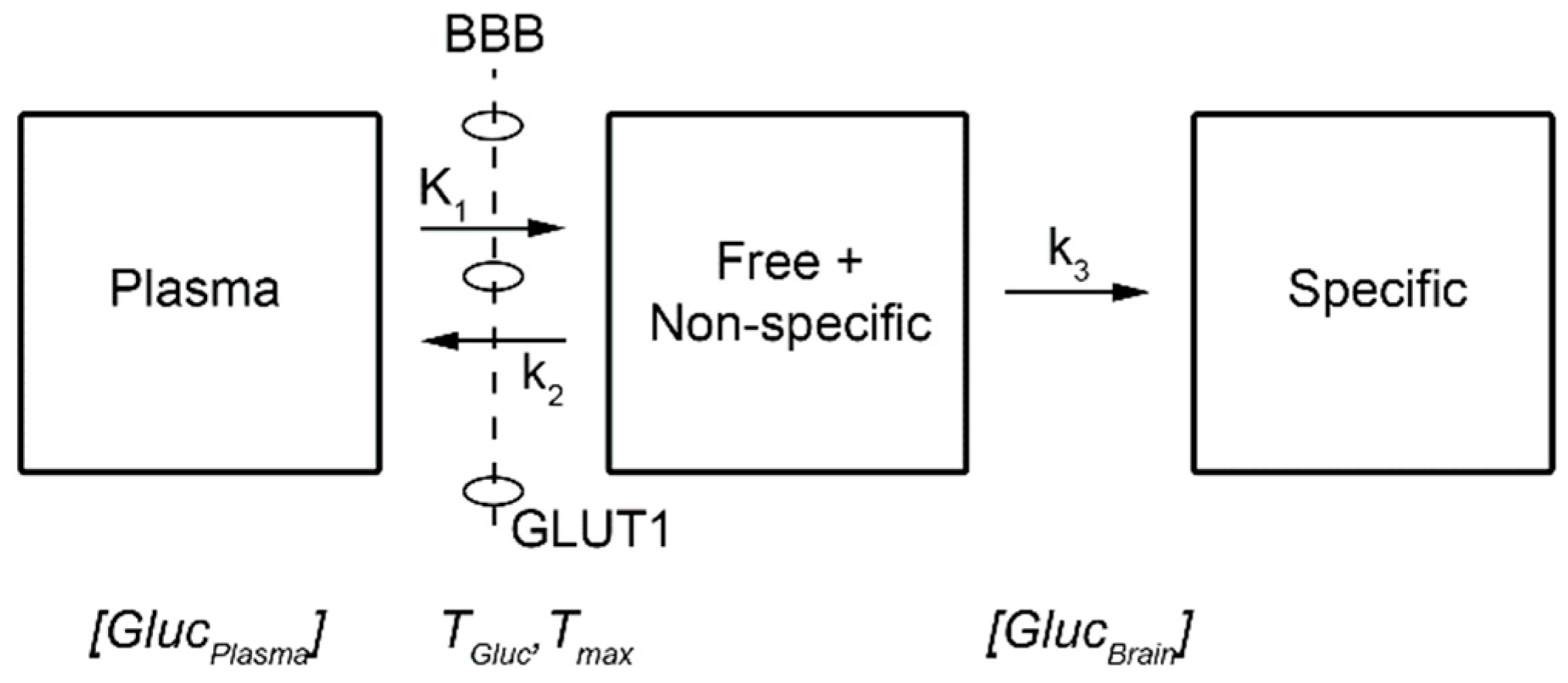

Basal Glucose Metabolism in the Human Brain

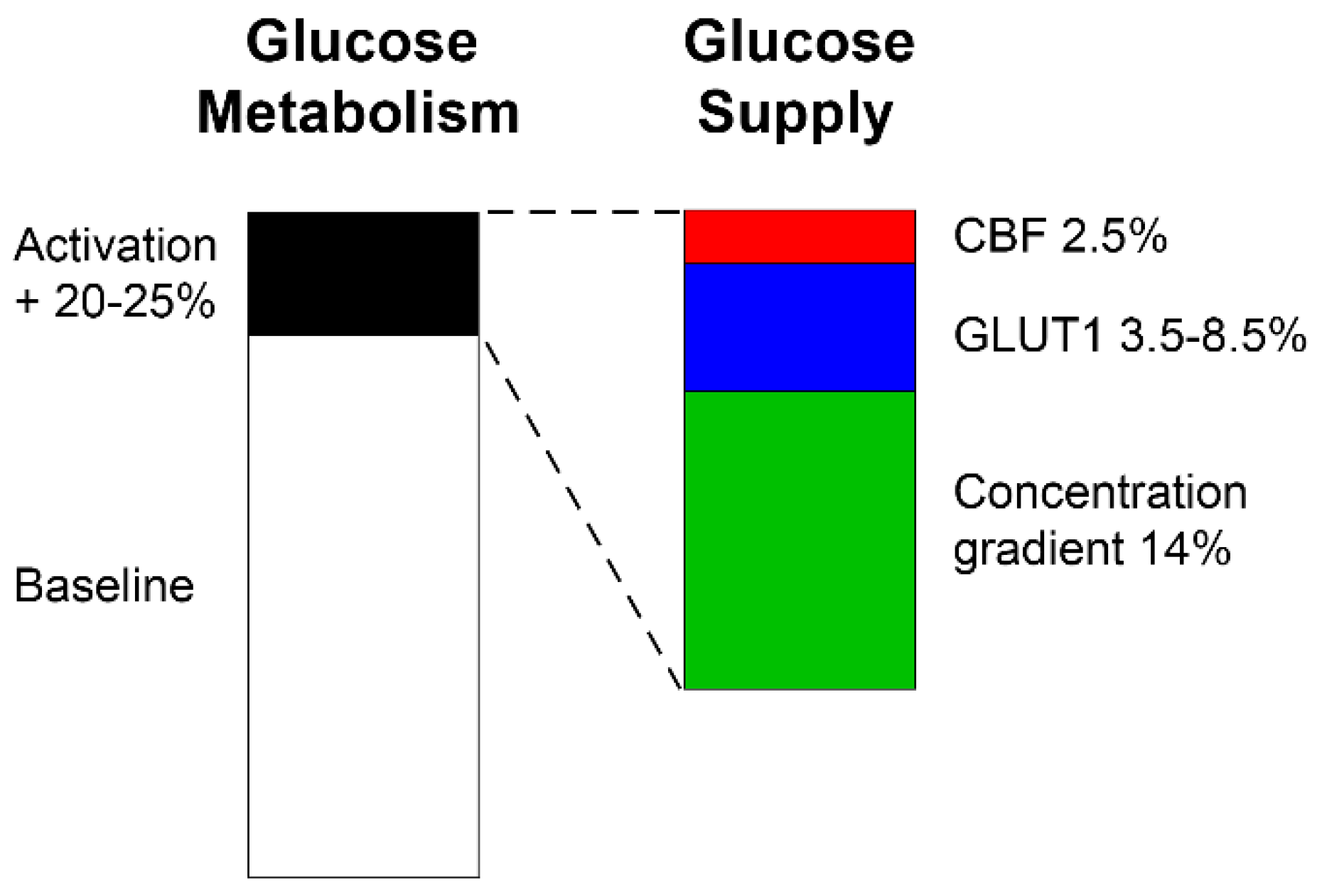

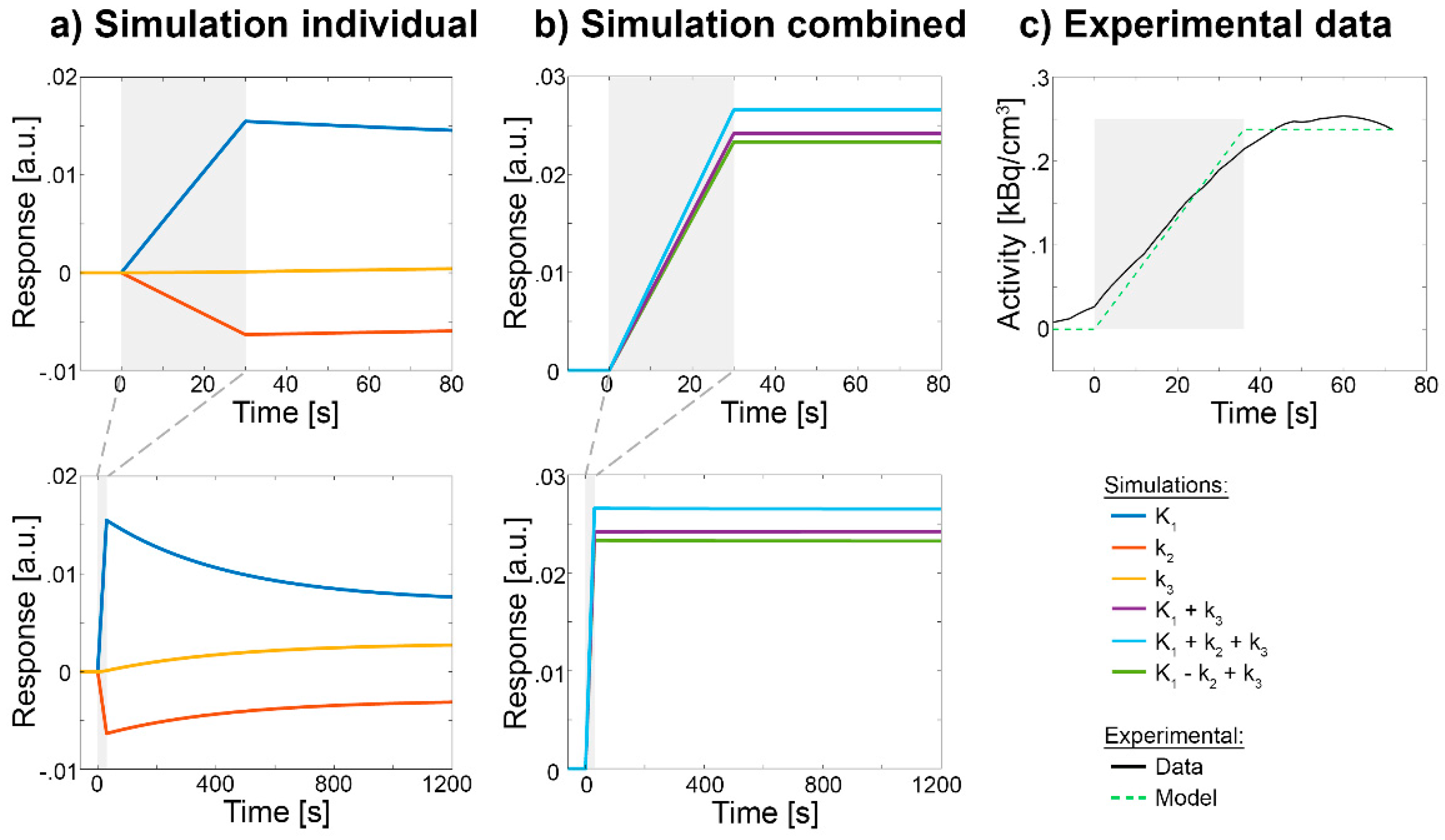

Stimulation-Specific Changes in [18F]FDG

- Cerebral blood flow (CBF)

- Glucose concentration gradient

- Intrinsic properties of GLUT1

- Number of GLUT1

Resting-State Dynamics of [18F]FDG

- Moment-to-moment fluctuations in [18F]FDG

Limitations, Outlook and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Data and Code Availability

References

- Wadsak W, Mitterhauser M. Basics and principles of radiopharmaceuticals for PET/CT. Eur J Radiol. Mar 2010;73(3):461-469. [CrossRef]

- Buerkle A, Weber WA. Imaging of tumor glucose utilization with positron emission tomography. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2008-12-01 2008;27(4):545-554. [CrossRef]

- Guedj E, Varrone A, Boellaard R, et al. EANM procedure guidelines for brain PET imaging using [(18)F]FDG, version 3. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. Jan 2022;49(2):632-651. [CrossRef]

- Villien M, Wey HY, Mandeville JB, et al. Dynamic functional imaging of brain glucose utilization using fPET-FDG. Neuroimage. Oct 15 2014;100:192-199.

- Hahn A, Gryglewski G, Nics L, et al. Quantification of Task-Specific Glucose Metabolism with Constant Infusion of 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med. Dec 2016;57(12):1933-1940. [CrossRef]

- Jamadar SD, Ward PG, Li S, et al. Simultaneous task-based BOLD-fMRI and [18-F] FDG functional PET for measurement of neuronal metabolism in the human visual cortex. Neuroimage. Apr 1 2019;189:258-266.

- Rischka L, Gryglewski G, Pfaff S, et al. Reduced task durations in functional PET imaging with [(18)F]FDG approaching that of functional MRI. Neuroimage. Jun 30 2018;181:323-330. [CrossRef]

- Hahn A, Reed MB, Vraka C, et al. High-temporal resolution functional PET/MRI reveals coupling between human metabolic and hemodynamic brain response. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. Dec 6 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dienel GA. Brain Glucose Metabolism: Integration of Energetics with Function. Physiol Rev. Jan 1 2019;99(1):949-1045. [CrossRef]

- Jamadar S, Behler A, Deery H, Breakspear PM. The metabolic costs of cognition. 2024-07-22 2024. [CrossRef]

- Simpson IA, Carruthers A, Vannucci SJ. Supply and Demand in Cerebral Energy Metabolism: The Role of Nutrient Transporters. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2007-11-01 2007;27(11):1766-1791. [CrossRef]

- Patching SG. Glucose Transporters at the Blood-Brain Barrier: Function, Regulation and Gateways for Drug Delivery. Molecular Neurobiology. 2017-03-01 2017;54(2):1046-1077. [CrossRef]

- Koepsell H. Glucose transporters in brain in health and disease. Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology. 2020-09-01 2020;472(9):1299-1343. [CrossRef]

- Leybaert L. Neurobarrier coupling in the brain: a partner of neurovascular and neurometabolic coupling? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Jan 2005;25(1):2-16.

- Rothman DL, Dienel GA, Behar KL, et al. Glucose sparing by glycogenolysis (GSG) determines the relationship between brain metabolism and neurotransmission. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. May 2022;42(5):844-860. [CrossRef]

- Barros LF, Porras OH, Bittner CX. Why glucose transport in the brain matters for PET. Trends in Neurosciences. 2005-03-01 2005;28(3):117-119. [CrossRef]

- Leybaert L, De Bock M, Van Moorhem M, Decrock E, De Vuyst E. Neurobarrier coupling in the brain: Adjusting glucose entry with demand. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2007 2007;85(15):3213-3220.

- Barros LF, Bittner CX, Loaiza A, Porras OH. A quantitative overview of glucose dynamics in the gliovascular unit. Glia. Sep 2007;55(12):1222-1237. [CrossRef]

- Furler SM, Jenkins AB, Storlien LH, Kraegen EW. In vivo location of the rate-limiting step of hexose uptake in muscle and brain tissue of rats. Am J Physiol. Sep 1991;261(3 Pt 1):E337-347. [CrossRef]

- Robinson PJ, Rapoport SI. Glucose transport and metabolism in the brain. Am J Physiol. Jan 1986;250(1 Pt 2):R127-136. [CrossRef]

- Gruetter R, Novotny EJ, Boulware SD, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. 1H NMR studies of glucose transport in the human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. May 1996;16(3):427-438. [CrossRef]

- Dienel GA, Cruz NF. Contributions of glycogen to astrocytic energetics during brain activation. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2015-02-01 2015;30(1):281-298. [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson DR, Gardiner NJ. Glucose neurotoxicity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008-01 2008;9(1):36-45.

- Godbersen GM, Falb P, Klug S, et al. Non-invasive assessment of stimulation-specific changes in cerebral glucose metabolism with functional PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. Jul 2024;51(8):2283-2292. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Wilson GS. Rapid Changes in Local Extracellular Rat Brain Glucose Observed with an In Vivo Glucose Sensor. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997 1997;68(4):1745-1752. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Novotny EJ, Zhu XH, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. Localized 1H NMR measurement of glucose consumption in the human brain during visual stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Nov 1 1993;90(21):9896-9900. [CrossRef]

- Fox PT, Raichle ME, Mintun MA, Dence C. Nonoxidative glucose consumption during focal physiologic neural activity. Science. Jul 22 1988;241(4864):462-464. [CrossRef]

- Fang J, Ohba H, Hashimoto F, Tsukada H, Chen F, Liu H. Imaging mitochondrial complex I activation during a vibrotactile stimulation: A PET study using [(18)F]BCPP-EF in the conscious monkey brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Dec 2020;40(12):2521-2532. [CrossRef]

- Kessler RM. Imaging methods for evaluating brain function in man. Neurobiol Aging. May-Jun 2003;24 Suppl 1:S21-35; discussion S37-29.

- Mintun MA, Lundstrom BN, Snyder AZ, Vlassenko AG, Shulman GL, Raichle ME. Blood flow and oxygen delivery to human brain during functional activity: theoretical modeling and experimental data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jun 5 2001;98(12):6859-6864. [CrossRef]

- Fox PT, Raichle ME. Focal physiological uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism during somatosensory stimulation in human subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Feb 1986;83(4):1140-1144. [CrossRef]

- Li B, Freeman RD. Neurometabolic coupling between neural activity, glucose, and lactate in activated visual cortex. J Neurochem. Nov 2015;135(4):742-754. [CrossRef]

- Roche R, Salazar P, Martin M, Marcano F, Gonzalez-Mora JL. Simultaneous measurements of glucose, oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin in exposed rat cortex. J Neurosci Methods. Nov 15 2011;202(2):192-198. [CrossRef]

- Mann K, Deny S, Ganguli S, Clandinin TR. Coupling of activity, metabolism and behaviour across the Drosophila brain. Nature. May 2021;593(7858):244-248. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins RA, Mans AM, Davis DW, Hibbard LS, Lu DM. Glucose availability to individual cerebral structures is correlated to glucose metabolism. J Neurochem. Apr 1983;40(4):1013-1018. [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves RJ, Planas AM, Cremer JE, Cunningham VJ. Studies on the relationship between cerebral glucose transport and phosphorylation using 2-deoxyglucose. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Dec 1986;6(6):708-716. [CrossRef]

- Phelps ME, Kuhl DE, Mazziota JC. Metabolic mapping of the brain's response to visual stimulation: studies in humans. Science. Mar 27 1981;211(4489):1445-1448.

- Vlassenko AG, Rundle MM, Mintun MA. Human brain glucose metabolism may evolve during activation: findings from a modified FDG PET paradigm. Neuroimage. Dec 2006;33(4):1036-1041. [CrossRef]

- Mishra A, Reynolds JP, Chen Y, Gourine AV, Rusakov DA, Attwell D. Astrocytes mediate neurovascular signaling to capillary pericytes but not to arterioles. Nat Neurosci. Dec 2016;19(12):1619-1627. [CrossRef]

- Kleinfeld D, Mitra PP, Helmchen F, Denk W. Fluctuations and stimulus-induced changes in blood flow observed in individual capillaries in layers 2 through 4 of rat neocortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998-12-22 1998;95(26):15741-15746. [CrossRef]

- Vogel J, Kuschinsky W. Decreased Heterogeneity of Capillary Plasma Flow in the Rat Whisker-Barrel Cortex during Functional Hyperemia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 1996-11-01 1996;16(6):1300-1306. [CrossRef]

- Akgören N, Lauritzen M. Functional recruitment of red blood cells to rat brain microcirculation accompanying increased neuronal activity in cerebellar cortex. NeuroReport. November 8, 1999 1999;10(16):3257. [CrossRef]

- Barros LF, San Martín A, Ruminot I, et al. Near-critical GLUT1 and Neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2017 2017;95(11):2267-2274. [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch SG, Holm S, Pedersen HS, et al. The (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose lumped constant determined in human brain from extraction fractions of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose and glucose. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Aug 2001;21(8):995-1002. [CrossRef]

- Fellows LK, Boutelle MG, Fillenz M. Extracellular brain glucose levels reflect local neuronal activity: a microdialysis study in awake, freely moving rats. J Neurochem. Dec 1992;59(6):2141-2147. [CrossRef]

- McNay EC, Fries TM, Gold PE. Decreases in rat extracellular hippocampal glucose concentration associated with cognitive demand during a spatial task. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Mar 14 2000;97(6):2881-2885. [CrossRef]

- Barnes K, Ingram JC, Bennett MDM, Stewart GW, Baldwin SA. Methyl-beta-cyclodextrin stimulates glucose uptake in Clone 9 cells: a possible role for lipid rafts. Biochem J. 2004-03-01 2004;378(2):343-351. [CrossRef]

- Caliceti C, Zambonin L, Prata C, et al. Effect of plasma membrane cholesterol depletion on glucose transport regulation in leukemia cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41246. [CrossRef]

- Park M-S. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Human Glucose Transporter GLUT1. PLOS ONE. 28.04.2015 2015;10(4):e0125361.

- Mitrovic D, McComas SE, Alleva C, Bonaccorsi M, Drew D, Delemotte L. Reconstructing the transport cycle in the sugar porter superfamily using coevolution-powered machine learning. eLife. 2023-07-05 2023;12:e84805. [CrossRef]

- Hamrahian AH, Zhang J-Z, Elkhairi FS, Prasad R, Ismail-Beigi F. Activation of Glut1 Glucose Transporter in Response to Inhibition of Oxidative Phosphorylation: Role of Sites of Mitochondrial Inhibition and Mechanism of Glut1 Activation. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1999-08-15 1999;368(2):375-379.

- Barnes K, Ingram JC, Porras OH, et al. Activation of GLUT1 by metabolic and osmotic stress: potential involvement of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Journal of Cell Science. 2002-06-01 2002;115(11):2433-2442. [CrossRef]

- Mercado CL, Loeb JN, Ismail-Beigi F. Enhanced glucose transport in response to inhibition of respiration in Clone 9 cells. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 1989-07 1989;257(1):C19-C28. [CrossRef]

- Yan Q, Lu Y, Zhou L, et al. Mechanistic insights into GLUT1 activation and clustering revealed by super-resolution imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2018-07-03 2018;115(27):7033-7038. [CrossRef]

- Loaiza A, Porras OH, Barros LF. Glutamate Triggers Rapid Glucose Transport Stimulation in Astrocytes as Evidenced by Real-Time Confocal Microscopy. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003/08/13 2003;23(19):7337-7342. [CrossRef]

- Cornford EM, Nguyen EV, Landaw EM. Acute upregulation of blood-brain barrier glucose transporter activity in seizures. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2000-09 2000;279(3):H1346-H1354. [CrossRef]

- Shetty M, Loeb JN, Vikstrom K, Ismail-Beigi F. Rapid activation of GLUT-1 glucose transporter following inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation in clone 9 cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993-08-01 1993;268(23):17225-17232. [CrossRef]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(4):537-541. [CrossRef]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(27):9673-9678. [CrossRef]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2007;8(9):700-711.

- Margulies DS, Ghosh SS, Goulas A, et al. Situating the default-mode network along a principal gradient of macroscale cortical organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Nov 1 2016;113(44):12574-12579. [CrossRef]

- Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, et al. Correspondence of the brain's functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Aug 4 2009;106(31):13040-13045.

- Horwitz B, Duara R, Rapoport SI. Intercorrelations of glucose metabolic rates between brain regions: application to healthy males in a state of reduced sensory input. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Dec 1984;4(4):484-499. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh AR, Grady CL, Ungerleider LG, Haxby JV, Rapoport SI, Horwitz B. Network analysis of cortical visual pathways mapped with PET. J Neurosci. Feb 1994;14(2):655-666. [CrossRef]

- Reed M, Cocchi L, Knudsen G, et al. Connecting the Dots: Approaching a Standardized Nomenclature for Molecular Connectivity Combining Data and Literature. bioRxiv. 2024:2024.2005.2010.593490.

- Jamadar SD, Ward PGD, Liang EX, Orchard ER, Chen Z, Egan GF. Metabolic and Hemodynamic Resting-State Connectivity of the Human Brain: A High-Temporal Resolution Simultaneous BOLD-fMRI and FDG-fPET Multimodality Study. Cereb Cortex. May 10 2021;31(6):2855-2867.

- Sala A, Lizarraga A, Caminiti SP, et al. Brain connectomics: time for a molecular imaging perspective? Trends Cogn Sci. Apr 2023;27(4):353-366.

- Hahn A, Reed MB, Milz C, Falb P, Murgaš M, Lanzenberger R. A Unified Approach for Identifying PET-based Neuronal Activation and Molecular Connectivity with the functional PET toolbox. BioRxiv. 2024.

- Reed MB, Ponce de Leon M, Vraka C, et al. Whole-body metabolic connectivity framework with functional PET. Neuroimage. May 1 2023;271:120030. [CrossRef]

- Raichle ME. The restless brain. Brain Connect. 2011;1(1):3-12.

- Hu Y, Wilson GS. A Temporary Local Energy Pool Coupled to Neuronal Activity: Fluctuations of Extracellular Lactate Levels in Rat Brain Monitored with Rapid-Response Enzyme-Based Sensor. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997 1997;69(4):1484-1490. [CrossRef]

- Dienel GA. Lack of appropriate stoichiometry: Strong evidence against an energetically important astrocyte–neuron lactate shuttle in brain. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2017 2017;95(11):2103-2125. [CrossRef]

- Winkler EA, Nishida Y, Sagare AP, et al. GLUT1 reductions exacerbate Alzheimer's disease vasculo-neuronal dysfunction and degeneration. Nature Neuroscience. 2015-04 2015;18(4):521-530.

- Erickson MA, Banks WA. Blood–Brain Barrier Dysfunction as a Cause and Consequence of Alzheimer's Disease. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2013-10-01 2013;33(10):1500-1513.

- Szablewski L. Glucose Transporters in Brain: In Health and in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2017-01-01 2017;55(4):1307-1320. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Lachance BB, Mattson MP, Jia X. Glucose metabolic crosstalk and regulation in brain function and diseases. Progress in Neurobiology. 2021-09-01 2021;204:102089. [CrossRef]

- Kahl KG, Georgi K, Bleich S, et al. Altered DNA methylation of glucose transporter 1 and glucose transporter 4 in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2016-05-01 2016;76:66-73. [CrossRef]

- Cunnane SC, Trushina E, Morland C, et al. Brain energy rescue: an emerging therapeutic concept for neurodegenerative disorders of ageing. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2020-09 2020;19(9):609-633. [CrossRef]

- Hahn A, Reed MB, Pichler V, et al. Functional dynamics of dopamine synthesis during monetary reward and punishment processing. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41(11):2973-2985. [CrossRef]

- Hahn A, Reed MB, Murgas M, et al. Dynamics of human serotonin synthesis differentially link to reward anticipation and feedback. Mol Psychiatry. Aug 23 2024. [CrossRef]

- del Amo EM, Urtti A, Yliperttula M. Pharmacokinetic role of L-type amino acid transporters LAT1 and LAT2. Eur J Pharm Sci. Oct 2 2008;35(3):161-174. [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza R. Transport of Amino Acids Across the Blood-Brain Barrier. Frontiers in physiology. 2020;11:973. [CrossRef]

- Muzik O, Chugani DC, Chakraborty P, Mangner T, Chugani HT. Analysis of [C-11]alpha-methyl-tryptophan kinetics for the estimation of serotonin synthesis rate in vivo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Jun 1997;17(6):659-669. [CrossRef]

- Delescluse J, Simonnet MM, Ziegler AB, et al. A LAT1-Like Amino Acid Transporter Regulates Neuronal Activity in the Drosophila Mushroom Bodies. Cells. Aug 13 2024;13(16). [CrossRef]

- Hery F, Simonnet G, Bourgoin S, et al. Effect of nerve activity on the in vivo release of [3H]serotonin continuously formed from L-[3H]tryptophan in the caudate nucleus of the cat. Brain Res. Jun 22 1979;169(2):317-334. [CrossRef]

- Hamon M, Bourgoin S, Artaud F, Glowinski J. The role of intraneuronal 5-HT and of tryptophan hydroxylase activation in the control of 5-HT synthesis in rat brain slices incubated in K+-enriched medium. J Neurochem. Nov 1979;33(5):1031-1042.

- Morgenroth VH, 3rd, Boadle-Biber M, Roth RH. Tyrosine hydroxylase: activation by nerve stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Nov 1974;71(11):4283-4287.

- Neff NH, Hadjiconstantinou M. Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase modulation and Parkinson's disease. Prog Brain Res. 1995;106:91-97.

- Silberbauer L, Reed M, Murgas M, et al. Assessment of cerebral glucose metabolism and blood flow following acute citalopram challenge. Neuroscience Applied. 2022/01/01/ 2022;1:100682. [CrossRef]

- Duarte JM, Gruetter R. Characterization of cerebral glucose dynamics in vivo with a four-state conformational model of transport at the blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem. May 2012;121(3):396-406. [CrossRef]

- Gruetter R, Ugurbil K, Seaquist ER. Steady-state cerebral glucose concentrations and transport in the human brain. J Neurochem. Jan 1998;70(1):397-408. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham VJ, Hargreaves RJ, Pelling D, Moorhouse SR. Regional blood-brain glucose transfer in the rat: a novel double-membrane kinetic analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Jun 1986;6(3):305-314. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).