Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

3. Results

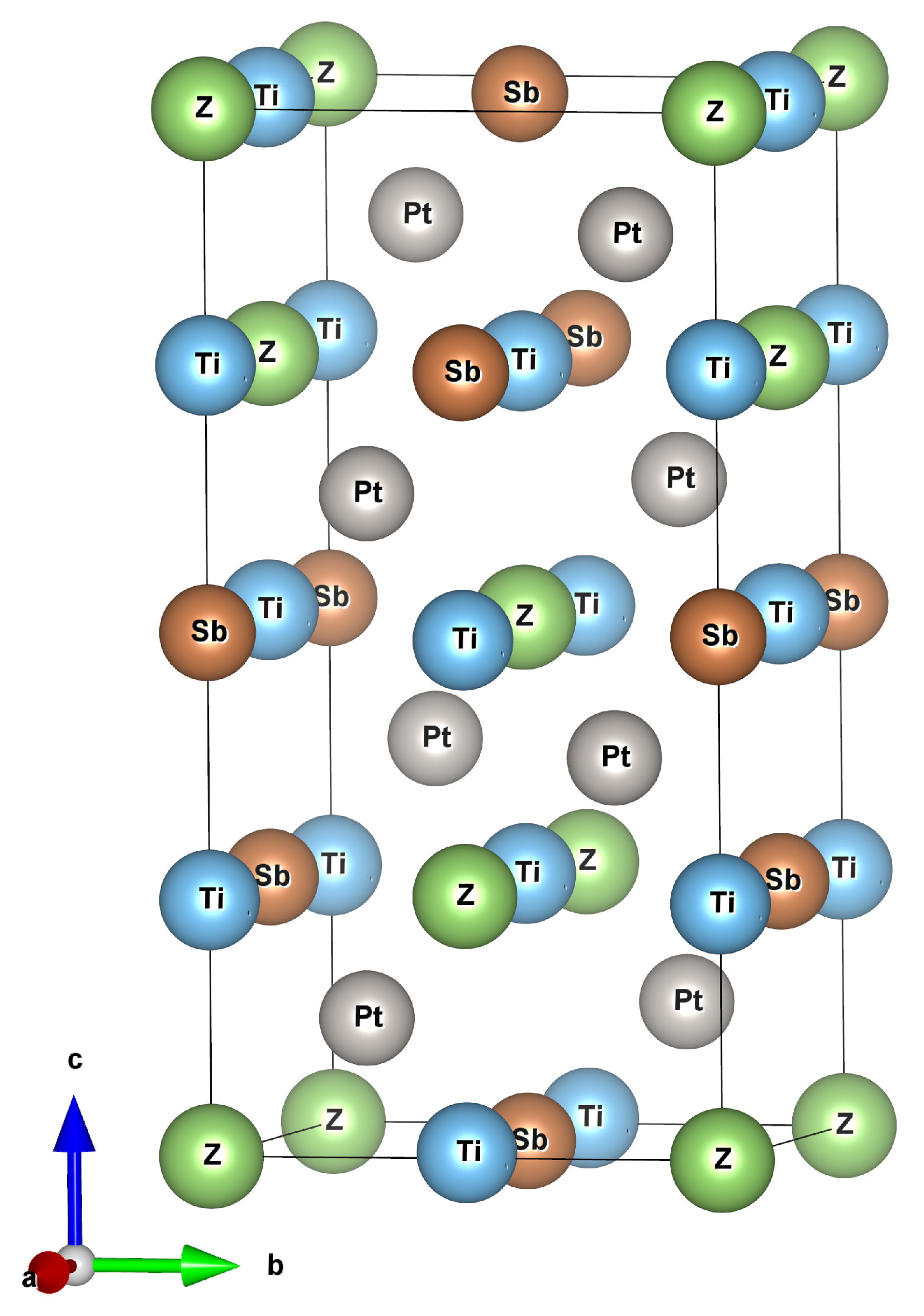

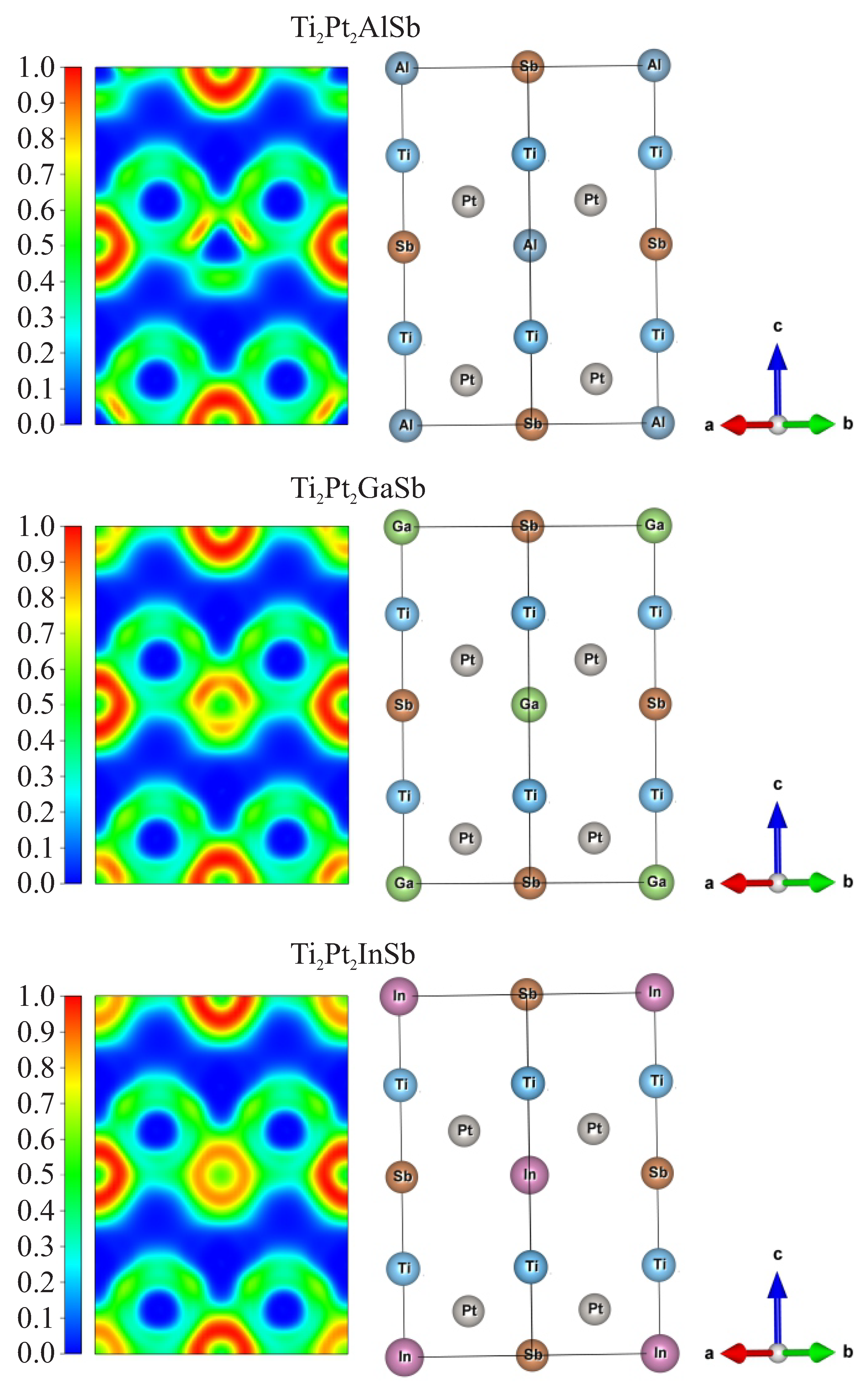

3.1. Structural Properties

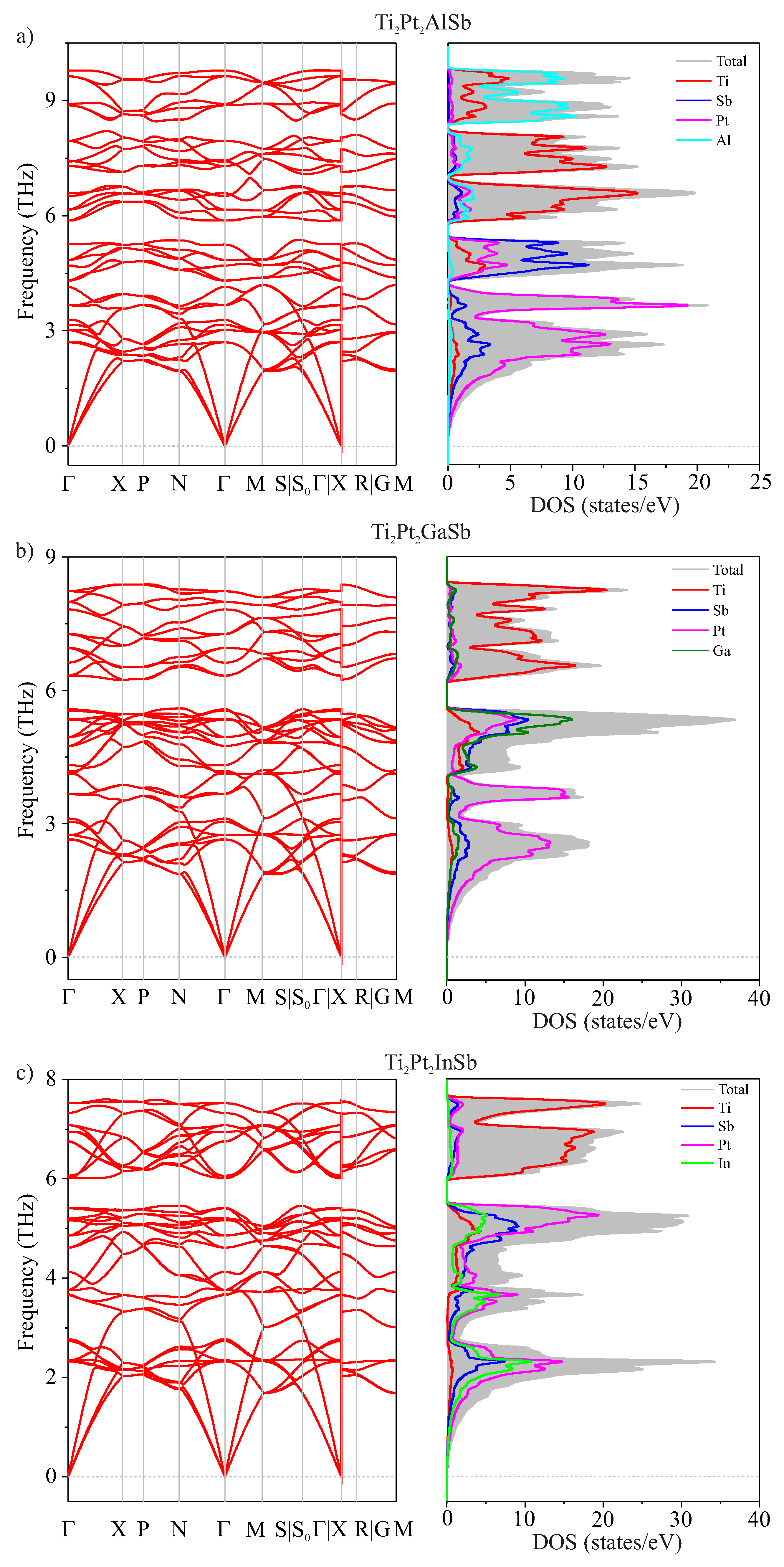

3.2. Vibrational Properties

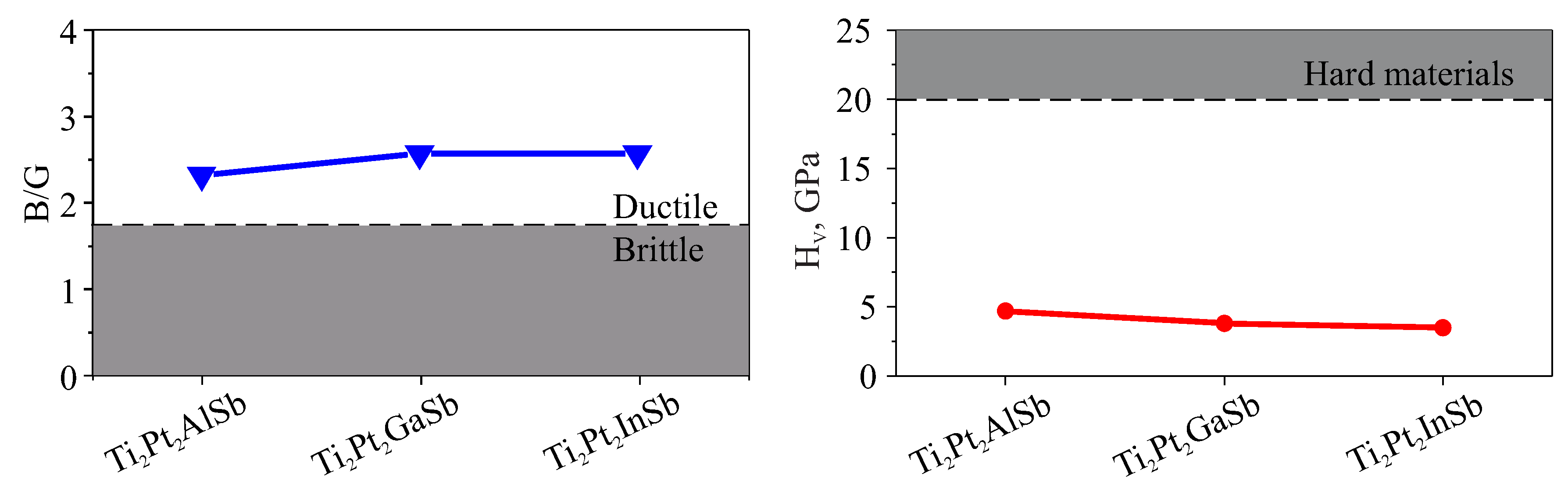

3.3. Elastic Properties

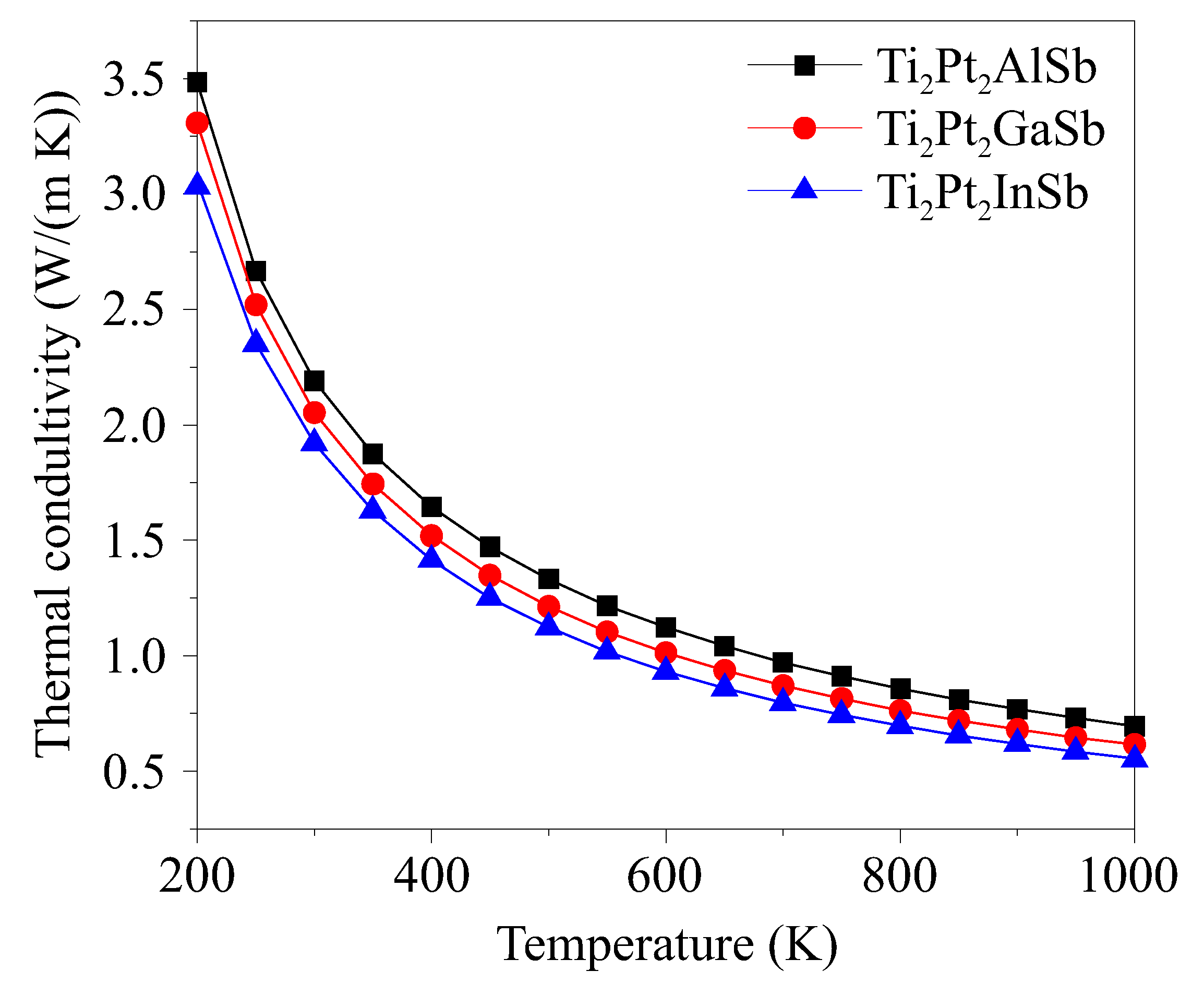

3.4. Thermal Conductivity

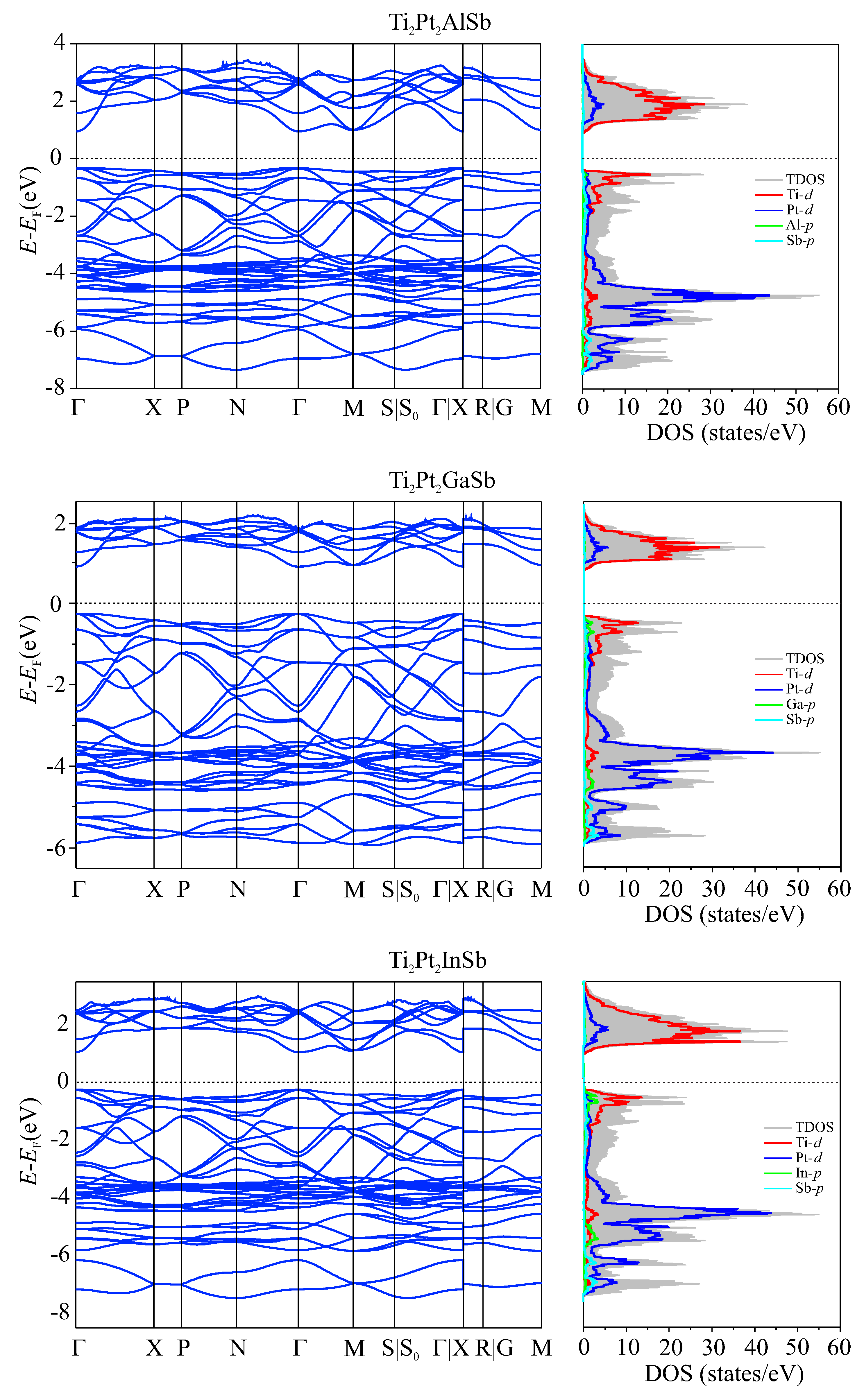

3.5. Electronic Properties

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Webster, P.J. Heusler alloys. Contemp. Phys. 1969, 10, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, S.; Yang, K.; Meyers, M.A. Heusler alloys: Past, properties, new alloys, and prospects. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 132, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elphick, K.; Frost, W.; Samiepour, M.; Kubota, T.; Takanashi, K.; Sukegawa, H.; Mitani, S.; Hirohata, A. Heusler alloys for spintronic devices: Review on recent development and future perspectives. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2021, 22, 235–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogl, G.; Grytsiv, A.; Gürth, M.; Tavassoli, A.; Ebner, C.; Wünschek, A.; Puchegger, S.; Soprunyuk, V.; Schranz, W.; Bauer, E.; et al. Mechanical properties of half-Heusler alloys. Acta Mater. 2016, 107, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuova, A.; Merali, N.; Abuova, F.; Khovaylo, V.; Sagatov, N.; Inerbaev, T. Electronic properties and chemical bonding in V2FeSi and Fe2VSi Heusler alloys. Crystals 2022, 12, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuova, F.; Inerbaev, T.; Abuova, A.; Merali, N.; Soltanbek, N.; Kaptagay, G.; Seredina, M.; Khovaylo, V. Structural, electronic, and magnetic properties of Mn2Co1-xVXZ (Z = Ga, Al) Heusler alloys: An insight from DFT study. Magnetochemistry 2021, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, F.; Graf, T.; Chadov, S.; Balke, B.; Felser, C. Half-Heusler compounds: Novel materials for energy and spintronic applications. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2012, 27, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangirbergen, A.; Amangeldi, N.; Revankar, S.T.; Yergaliuly, G. A review of irradiation-induced hardening in FeCrAl alloy systems for accident-tolerant fuel cladding. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 429, 113659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Wood, M.; Xia, Y.; Wolverton, C.; Snyder, G.J. Double half-Heuslers. Joule 2019, 3, 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeier, W.G.; Schmitt, J.; Hautier, G.; Aydemir, U.; Gibbs, Z.M.; Felser, C.; Snyder, G.J. Engineering half-Heusler thermoelectric materials using Zintl chemistry. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rached, Y.; Caid, M.; Merabet, M.; Benalia, S.; Rached, H.; Djoudi, L.; Mokhtari, M.; Rached, D. A comprehensive computational investigations on the physical properties of TiXSb (X: Ru, Pt) half-Heusler alloys and Ti2RuPtSb2 double half-Heusler. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2022, 122, e26875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R.; Park, T.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.-S.; Jo, S.; Lee, K.H. Enhanced Thermoelectric Properties of Ti2FeNiSb2 Double Half-Heusler Compound by Sn Doping. Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research 2022, 3, 2100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; El-Khouly, A.; Elsehly, E.M.; Almutib, E.N.; Elshamndy, S.K.; Serhiienko, I.; Argunov, E.V.; Sedegov, A.; Karpenkov, D.; Pashkova, D. Transport and thermoelectric properties of melt spinning synthesized M2FeNiSb2 (M= Ti, Hf) double half-Heusler alloys. Materials Research Bulletin 2023, 164, 112246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charifi, Z.; Baaziz, H.; Uğur, Ş.; Uğur, G. Prediction of the electronic structure, optical and vibrational properties of ScXCo2Sb2 (X= V, Nb, Ta) double half-Heusler alloys: a theoretical study. Indian Journal of Physics 2023, 97, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudjelal, M.; Bouhadjer, K.; Matougui, M.; Bentata, S.; Srivastata, V.; Bin-Omran, S.; Khenata, R. Ab initio prediction of the structural, optoelectronic, and thermoelectric properties of double half-Heusler (DHH) ScXRh2Bi2 (X= Nb, Ta) alloys DFT study results. Indian Journal of Physics 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhtiche, M.; Matougui, M.; Houari, M.; Bouadjemi, B.; Lantri, T.; Boudjelal, M.; Bentata, S. Predictive study of the new double half-Heusler compounds Hf2FeNiSb2, Nb2Co2GaSb, and ScNbCo2Sb2, promising candidates for thermoelectric applications. Indian J. Phys. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaf, M.; Righi, H.; Rached, H.; Rached, D.; Beddiaf, R. Ab initio study of the properties of Ti2PdFe (Ru) Sb2 double half-Heusler semiconducting alloys. Journal of Electronic Materials 2023, 52, 6514–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhadjer, K.; Boudjelal, M.; Matougui, M.; Bentata, S.; Lantri, T.; Batouche, M.; Seddik, T.; Khenata, R.; Bouadjemi, B.; Bin Omran, S.; et al. Structural, optoelectronic, thermodynamic and thermoelectric properties of double half-Heusler (DHH) Ti2FeNiSb2 and Ti2Ni2InSb compounds: A TB-mBJ study. Chin. J. Phys. 2023, 85, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.; Wu, B. Electronic structure, magnetism and disorder effect in double half-Heusler alloy Mn2FeCoSi2. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 555, 169367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douinat, O.; Boucherdoud, A.; Seghier, A.; Houari, M.; Mesbah, S.; Lantri, T.; Bestani, B. Theoretical investigation of the physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of Zr2XBiNi2 (X: Al, Ga) double half-Heusler alloys. Journal of Materials Research 2023, 38, 4509–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berarma, K.; Essaoud, S.S.; Al Azar, S.; Al-Reyahi, A.Y.; Mousa, A.A.; Mufleh, A. Computational characterization of structural, optoelectronic, and thermoelectric properties of some double half-Heusler alloys X2FeY′Sb2 (X: Hf, Zr; Y′: Ni, Pd). Phase Transitions 2023, 96, 806–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surucu, G.; Isik, M.; Candan, A.; Wang, X.; Gullu, H.H. Investigation of structural, electronic, magnetic, and lattice dynamical properties for XCoBi (X: Ti, Zr, Hf) half-Heusler compounds. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2020, 587, 412146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yang, C.-L.; Wang, M.-S.; Ma, X.-G.; Yi, Y.-G. Effect of M elements (M = Ti, Zr, and Hf) on thermoelectric performance of the half-Heusler compounds MCoBi. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2019, 52, 255501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; He, R.; Mao, J.; Zhu, Q.; Li, C.; Sun, J.; Ren, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Z.; et al. Discovery of ZrCoBi based half-Heuslers with high thermoelectric conversion efficiency. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radouan, D.; Besbes, A.; Bestani, B. Investigation on electronic and thermoelectric properties of (P, As, Sb) doped ZrCoBi. East Eur. J. Phys. 2021, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996, 6, 15–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togo, A.; Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 2015, 108, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Oganov, A.R. AICON: A program for calculating thermal conductivity quickly and accurately. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2020, 251, 107074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Xia, K.; Hegde, V.I.; Aydemir, U.; Kocevski, V.; Zhu, T.; Wolverton, C.; Snyder, G.J. A valence balanced rule for discovery of 18-electron half-Heuslers with defects. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1480–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Huang, K. Dynamical Theory of Crystal Lattices; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, W. Lehrbuch der Kristallphysik (Textbook of crystal physics). BG Teubner, Leipzig und Berlin 1928.

- Reuss, A.J.Z. Calculation of the flow limits of mixed crystals on the basis of the plasticity of monocrystals. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 1929, 9, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. The elastic behaviour of a crystalline aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. A 1952, 65, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. Elastic properties of reinforced solids: some theoretical principles. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1963, 11, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, L.; Long, J. First-principles investigation of the elastic, Vickers hardness, and thermodynamic properties of Al–Cu intermetallic compounds. Superlattices Microstruct. 2015, 79, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantsevich, I.N. Elastic constants and elastic moduli of metals and insulators. Reference Book; Naukova Dumka: 1982.

- Ranganathan, S.I.; Ostoja-Starzewski, M. Universal elastic anisotropy index. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 055504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Niu, S.; Oganov, A.R. Simple and accurate model of fracture toughness of solids. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 125, 06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, M.E.; Brown, L.D.; Marcus, H.L. Elastic constants versus melting temperature in metals. Scr. Metall. 1984, 18, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasmahapatra, A.; Daga, L.E.; Karttunen, A.J.; Maschio, L.; Casassa, S. Key role of defects in thermoelectric performance of TiMSn (M= Ni, Pd, and Pt) half-Heusler alloys. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 14997–15006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Dong, Z.; Gao, M.; Luo, J.; Yang, J. Screening of half-Heuslers with temperature-induced band convergence and enhanced thermoelectric properties. arXiv Prepr. 2024, arXiv:2407.00433.

- Gautier, R.; Zhang, X.; Hu, L.; Yu, L.; Lin, Y.; Sunde, T.O.L.; Chon, D.; Poeppelmeier, K.R.; Zunger, A. Prediction and accelerated laboratory discovery of previously unknown 18-electron ABX compounds. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukau, Aliaksandr V and Vydrov, Oleg A and Izmaylov, Artur F and Scuseria, Gustavo E. Influence of the exchange screening parameter on the performance of screened hybrid functionals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2006, 125.

| Compounds | Ti2Pt2AlSb | Ti2Pt2GaSb | Ti2Pt2InSb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice | a = b | 6.120 | 6.121 | 5.905 |

| parameter | c | 12.228 | 12.216 | 11.826 |

| Coordinates | x | y | z | |

| Atoms | Ti | 0 | 0.5 | 0.495 |

| Pt | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.625 | |

| Al/Ga/In | 0 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |

| Sb | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | |

| Mulliken symbol | Activity | , THz | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti2Pt2AlSb | Ti2Pt2GaSb | Ti2Pt2InSb | ||

| E | Raman, IR | 2.700 | 2.644 | 2.322 |

| E | Raman,IR | 3.023 | 2.750 | 2.322 |

| Raman | 3.158 | 3.049 | 2.768 | |

| Raman, IR | 3.287 | 3.116 | 2.732 | |

| Silent | 3.666 | 3.672 | 3.671 | |

| Raman | 3.678 | 3.674 | 3.658 | |

| Silent | 4.147 | 4.192 | 4.125 | |

| E | Raman,IR | 4.312 | 4.127 | 3.759 |

| Raman | 4.704 | 4.318 | 3.763 | |

| E | Raman,IR | 4.848 | 4.749 | 4.615 |

| Raman, IR | 5.251 | 5.358 | 5.163 | |

| E | Raman,IR | 5.874 | 4.949 | 4.862 |

| E | Raman,IR | 6.162 | 5.334 | 5.198 |

| Raman, IR | 6.512 | 5.544 | 5.411 | |

| Raman | 6.587 | 5.572 | 5.406 | |

| E | Raman,IR | 7.295 | 6.330 | 6.010 |

| Raman | 7.414 | 7.269 | 6.750 | |

| Silent | 7.433 | 7.265 | 6.756 | |

| E | Raman,IR | 7.952 | 6.953 | 6.946 |

| E | Raman,IR | 8.874 | 7.991 | 7.079 |

| Raman, IR | 8.914 | 6.625 | 6.059 | |

| E | Raman,IR | 9.634 | 8.231 | 7.323 |

| Raman | 9.783 | 7.824 | 7.523 | |

| Compounds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti2Pt2AlSb | 199.6 | 111.5 | 108.6 | 196.5 | 69.1 | 68 |

| Ti2Pt2GaSb | 194.2 | 115.2 | 113.5 | 191.7 | 66.9 | 66.9 |

| Ti2Pt2InSb | 191.3 | 106.6 | 106.9 | 188.8 | 58.6 | 59 |

| Compounds | B | G | E | B/G | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti2Pt2AlSb | 139 | 58 | 152 | 0.318 | 2.4 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 0.01 | 2.26 | 1248 |

| Ti2Pt2GaSb | 140 | 54 | 144 | 0.329 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 2.4 | 0.01 | 3.25 | 1224 |

| Ti2Pt2InSb | 135 | 51 | 136 | 0.331 | 2.6 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 0.01 | 1.38 | 1211 |

| TiPtSn | 146 | 57 | 150 | 0.329 | 2.5 | 4.7 | – | 0.00 | 1.72 | – |

| Compounds | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti2Pt2AlSb | 2.67 | 4847 | 2505 | 2911 | this study |

| Ti2Pt2GaSb | 2.52 | 4653 | 2349 | 2732 | this study |

| Ti2Pt2InSb | 2.35 | 4523 | 2273 | 2661 | this study |

| TiPtSn | 9.2 | 4553 | 2569 | 2924 | [43] |

| Compounds | Ti | Pt | Z | Sb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti2Pt2AlSb | +1.99 | -3.59 | +3 | +0.20 |

| Ti2Pt2GaSb | +1.98 | -3.62 | +3 | +0.28 |

| Ti2Pt2InSb | +1.94 | -3.63 | +3 | +0.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).