1. Introduction

Streptococcus suis is an important emerging zoonotic agent that causes septicemia, meningitis, endocarditis, arthritis, septicemia, meningitis, and even sudden death in humans. Although

S. suis is considered a major swine pathogen, it is increasingly isolated from a wide range of mammalian species and from birds[

1].

Streptococcus suis has spread worldwide and has caused enormous economic losses in the swine industry in recent years because it causes high morbidity and mortality[

2].

Streptococcus suis infections in humans are most often restricted to workers in close contact with pigs or swine byproducts[

3]. However, two extensive outbreaks of

S. suis serotype 2 (SS2) in humans in China in 1998 and 2005 raised serious concerns for public health, and have changed our perception of human SS2 infections as only sporadic[

1,

4]. Among all of the known strains of

S. suis, serotype 2 mainly infects swine and humans[

5]. Serotype 2 is the serotype most frequently isolated from diseased pigs in the majority of countries[

6], and most research has focused on this serotype[

5]. However, the molecular pathogenesis of

S. suis-induced infectious disease is still unclear and our understanding of it is fragmentary[

4,

7], which hampers our attempts to control the diseases caused by

S. suis[

8].

A repertoire of

S. suis virulence determinants undoubtedly plays a role in human infections because

S. suis is suggested to cause community-acquired disease[

9]. Many SS2 virulence factors have been reported, some of which are considered critical, including glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh), suilysin (Sly), Eno, and capsular polysaccharide (Cps)[

10]. For example, a deficiency of O-acetyl-homoserine sulfhydrylase (OAHS) reduces the expression of Eno, and thus, inhibits SC19-induced endothelial cell apoptosis, and ultimately alleviates the damage caused by SC19 to the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Although the virulence of SC19-ΔOahs is significantly reduced, it still induces a good immune response in mice against infection by a homologous strain[

11]. Cps not only forms the basis for serotyping but also protects the bacterium from phagocytosis[

12]. Catabolite control protein A (CcpA) is involved in metabolic gene regulation in various bacteria[

13], and is the major mediator of carbon catabolite repression (CCR), repressing gene expression in response to excess sugar during growth[

14,

15,

16]. Bacterial growth, hemolysin production, biofilm formation, and capsule expression are also influenced by CcpA depletion in other streptococci[

17,

18]. CcpA only indirectly affects certain pathogenic proteins, thus, reducing virulence[

19]. Although several virulence factors have been shown to play roles in the early stages of infection, the roles of other virulence factors remain unclear[

20]. Therefore, further investigation of the pathogenesis of known and unknown virulence factors will extend our understanding of the pathogenesis and prevent infection by this bacterium[

21].

In a previous study, we analyzed the genomic sequences of 1,634

S. suis isolates from 14 countries and classified them into nine Bayesian analysis of population structure (BAPS) groups. Among them, BAPS group 7 represented a dominant group of virulent

S. suis associated with human infections, which were most commonly sequence type 1 (ST1) and ST7 (included in clonal complex 1 [CC1]). We proposed that this cluster constituted a novel human-associated clade (HAC) that had diversified from swine

S. suis isolates. A genome-wide association study was used to identify 25 HAC-specific genes. These genes may contribute to an increased risk of human infection and could be used as markers for HAC identification[

22]. The

G22 gene, annotated as a secretory protein gene, was one of these 25 HAC-specific genes. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the

G22 protein plays a crucial role in the pathogenicity of SS2 and that its inactivation may lead to attenuation of virulence. Specifically, we propose that the G22 protein contributes to the virulence of S. suis by modulating the expression of key virulence factors and influencing host-pathogen interactions. To test this hypothesis and clarify the biological functions of the

G22 protein, we used homologous recombination to construct a gene knockout mutant, ΔG22, of SC19. Comprehensive experiments showed clear morphological changes and the attenuation of pathogenicity in the mutant strain. An RNA sequencing analysis suggested that the inactivation of

G22 resulted in the up- or downregulation of many genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism or encoding virulence-related factors. Our results provide new insights into the pathogenesis of SS2 and extend our understanding of this pathogen.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Plasmids

The S. suis strain and plasmids used in this study are available in

Table 1. In this study, we used SS2 strain SC19, one of the representative Chinese virulent strains that were isolated from a diseased pig during an outbreak in the Sichuan province of China[

23]. The SS2 strains were cultured at 37 ℃ in tryptic soy broth (TSB) or on tryptic soy agar (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) (TSA) plates containing 10% newborn bovine serum (Sijiqing Biological Engineering Materials Co. Ltd., Hangzhou, China). E. coli strains were cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB agar plates at 37 ℃. According to the requirement of antibiotics, spectinomycin (Spc, sigma, USA) were applied at the dose of 100 μg/mL for S. suis, and 50 μg/mL for E. coli. DMEM culture medium (Gibco, Invitrogen, USA) including 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco, USA) was used to culture the human laryngeal epithelial cell line (HEp-2) and Raw264.7 macrophage cell line at 37 ℃ in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. . SS2 strain SC19 was selected as the wild-type (WT) strain. Strain SC19 and the

G22-deletion mutant ∆G22 were cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB) or on tryptic soy agar (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) plates containing 10% newborn bovine serum (Sijiqing Biological Engineering Materials Co. Ltd., Hangzhou, China) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. When the pSET4s plasmid contained the spectinomycin (Spc), the concentration of Spc in the medium was 100 µg/mL.

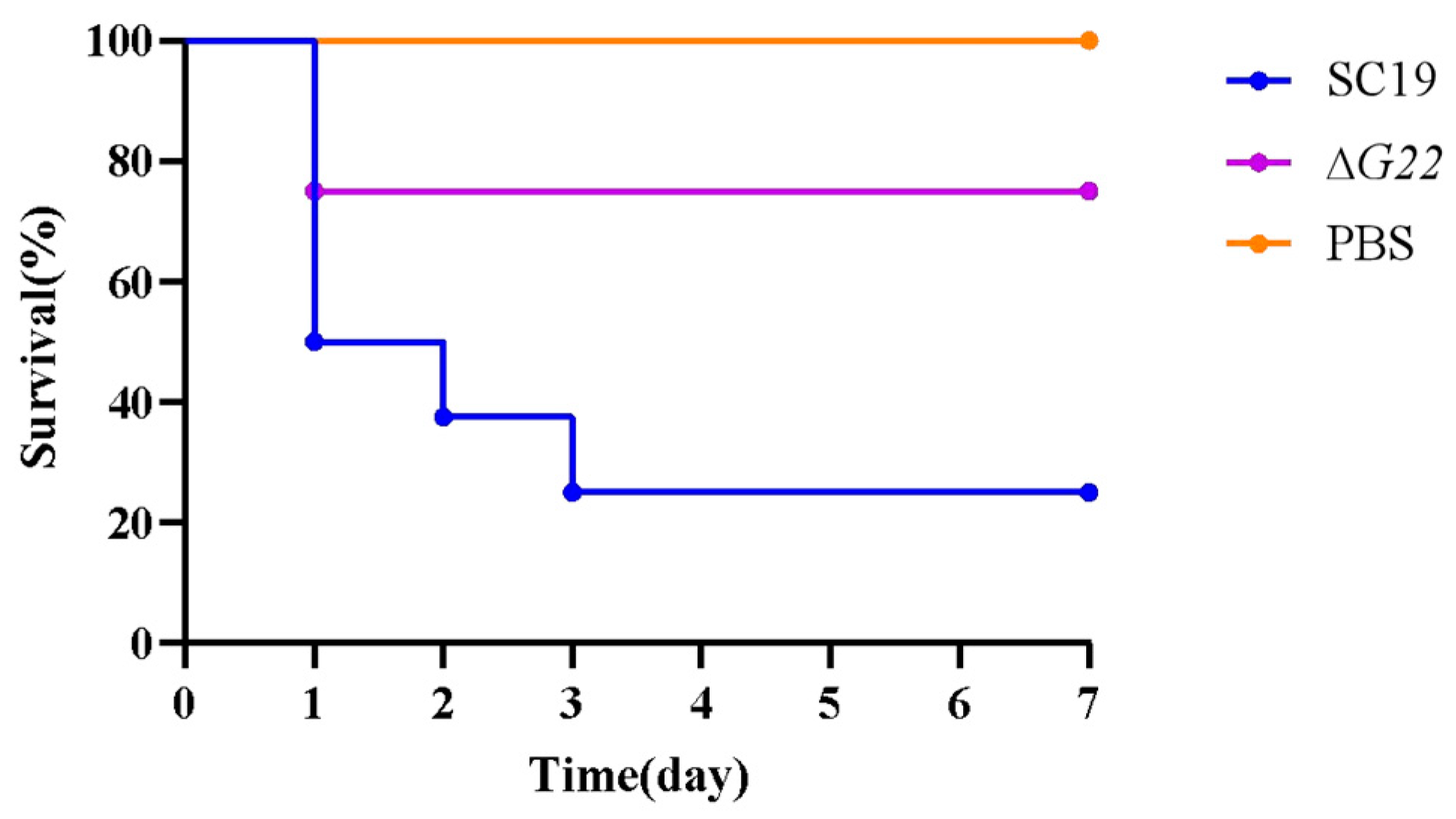

2.2. Construction of G22 Gene Knockout Strain and Complementary Strain

To create a deletion of G22 in the SC19 strains, we utilized the thermosensitive suicide vector pSET4s, derived from S. suis-E. coli[

24] .Initially, specific primers outlined in

Table 2 were employed to amplify the two flanking regions adjacent to the target gene. Subsequently, these regions were fused through overlap-extension PCR. Following purification, the resultant PCR products were treated with BamH1 and EcoRI restriction enzymes. Concurrently, the temperature-sensitive vector pSET4s was ligated with the digested PCR fragments to facilitate cloning of the desired gene. Electroporation was then utilized to introduce the recombinant vectors into competent SS2 SC19 cells. Cultivation of the transformed cells took place at 28 °C in media supplemented with Cm and Spc. We subsequently screened for vector-loss mutants, which had undergone homologous recombination via a double crossover event, replacing their wild-type (WT) allele with a genetic segment harboring the G22 deletion. Verification of the mutant cells was carried out using PCR with primer pairs W1/W2 (to differentiate between the WT and mutant based on amplicon size) and N1/N2 (to confirm the absence of G22).

For complementation purposes, the target gene along with its putative promoter sequences were amplified from the SC19 genome via PCR and cloned into the

E. coli-S. suis shuttle vector pSET2[

25], generating recombinant plasmids. These plasmids were then electroporated into the ΔG22 mutant cells. Furthermore, complementation strains (CΔG22) were selected using spectinomycin and validated by PCR. The sequences of all primers utilized in this study are detailed in

Table 2.

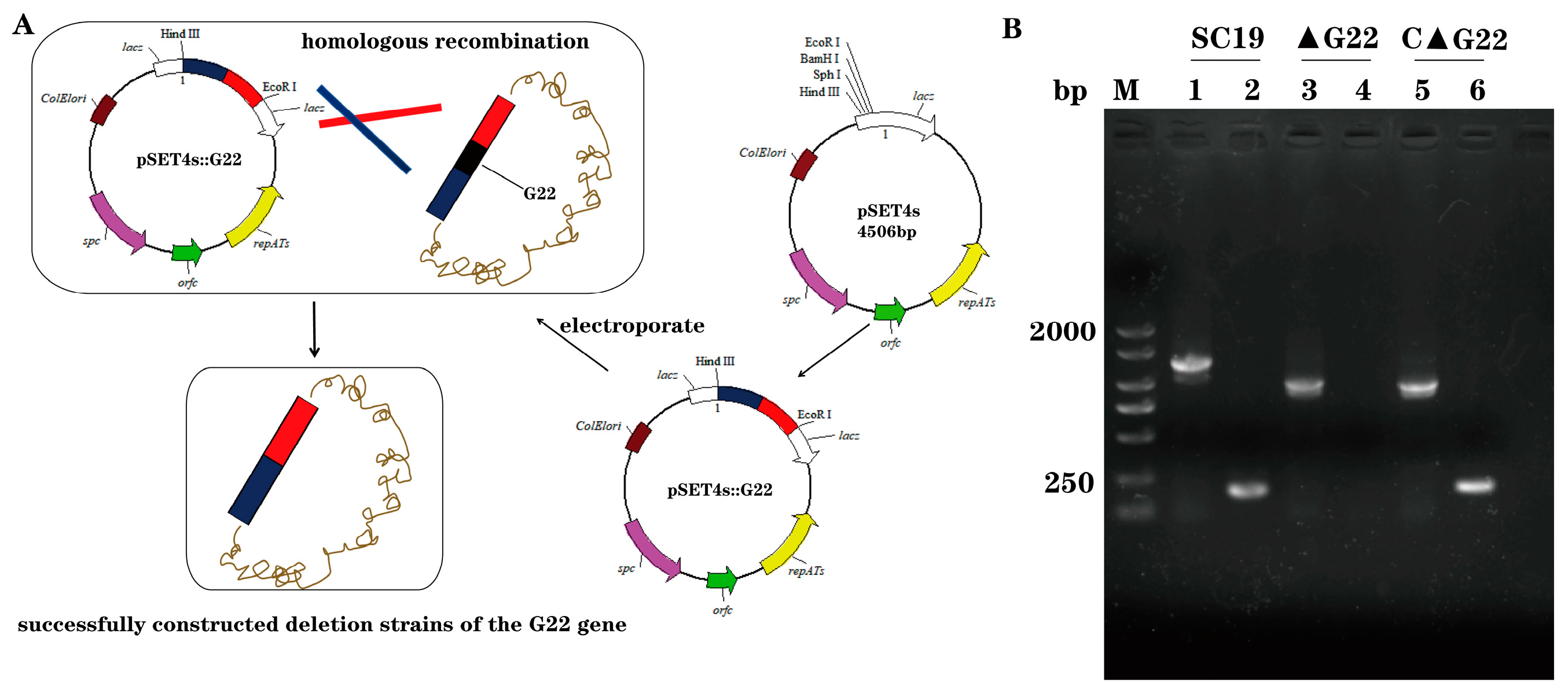

2.3. Growth characteristics and genetic stability of mutant strains

The experiment involved the separate inoculation of wild-type strain SC19, its mutant derivative ΔG22, and the complemented strain CΔG22, each diluted to a 1:100 ratio, into 100 ml aliquots of Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB). These cultures were then incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm/min. To monitor bacterial growth, optical density measurements at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600) were taken using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (Smart Spec Plus, Bio-Rad, USA) every hour for a duration of 20 hours. This experimental setup was repeated across three independent biological replicates to ensure reliability of the results.

2.4. Observation with Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses were conducted following established protocols[

26]. Cells from Streptococcus suis type 2 strains SC19, ΔG22, and CΔG22 were collected at an optical density (OD

600) of 0.6 and subsequently fixed overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Following this, the samples underwent post-fixation with 2% osmium tetroxide for two hours and were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series. The dehydrated specimens were then embedded in epoxy resin for sectioning. Ultrastructural examinations were performed using an H-7650 TEM instrument (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) to assess the morphological features of the bacterial cells.

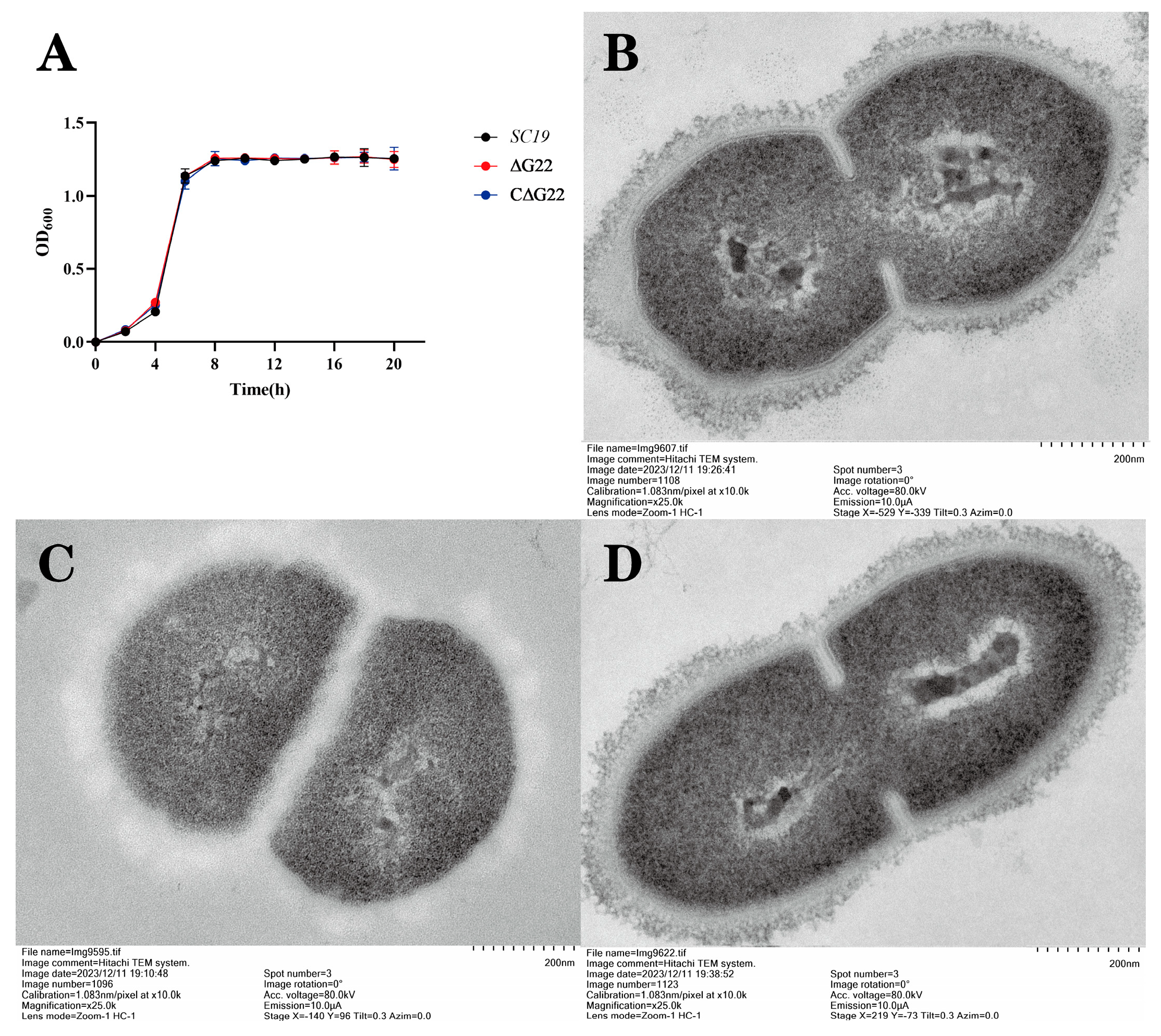

2.5. Survival Assays of SS2 in H2O2, at High Temperature, and Under Acidic Conditions

To assess stress tolerance, we executed the following methodology. Initially, bacterial suspensions of the wild-type (WT), ΔG22 mutant, and complemented CΔG22 strains were propagated and adjusted to an OD600 nm of 0.6 in TSB medium. Subsequently, 100 μL aliquots of each strain were individually subjected to various stress conditions: heat stress at temperatures of 40 °C, 41 °C, and 42 °C; acid stress mediated by acetic acid at pH 4, pH 5, and pH 6, all maintained at 37 °C; and oxidative stress induced by 10 mM H2O2 also at 37 °C. These stressed cultures were incubated for 1 hour under their respective conditions. Concurrently, untreated strains were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour, serving as negative controls. To quantify the stress-induced survival, serial dilutions of the bacterial suspensions from all conditions were plated onto TSB agar plates. The colony-forming units (CFU) counts under each stress scenario were then determined. The survival rate under a given stress was calculated as a percentage, using the formula: [(CFU under stress) / (CFU in negative control)] × 100%, adopting a previously established methodology[

27]. This experimental protocol was independently replicated three times to ensure reproducibility and statistical robustness.

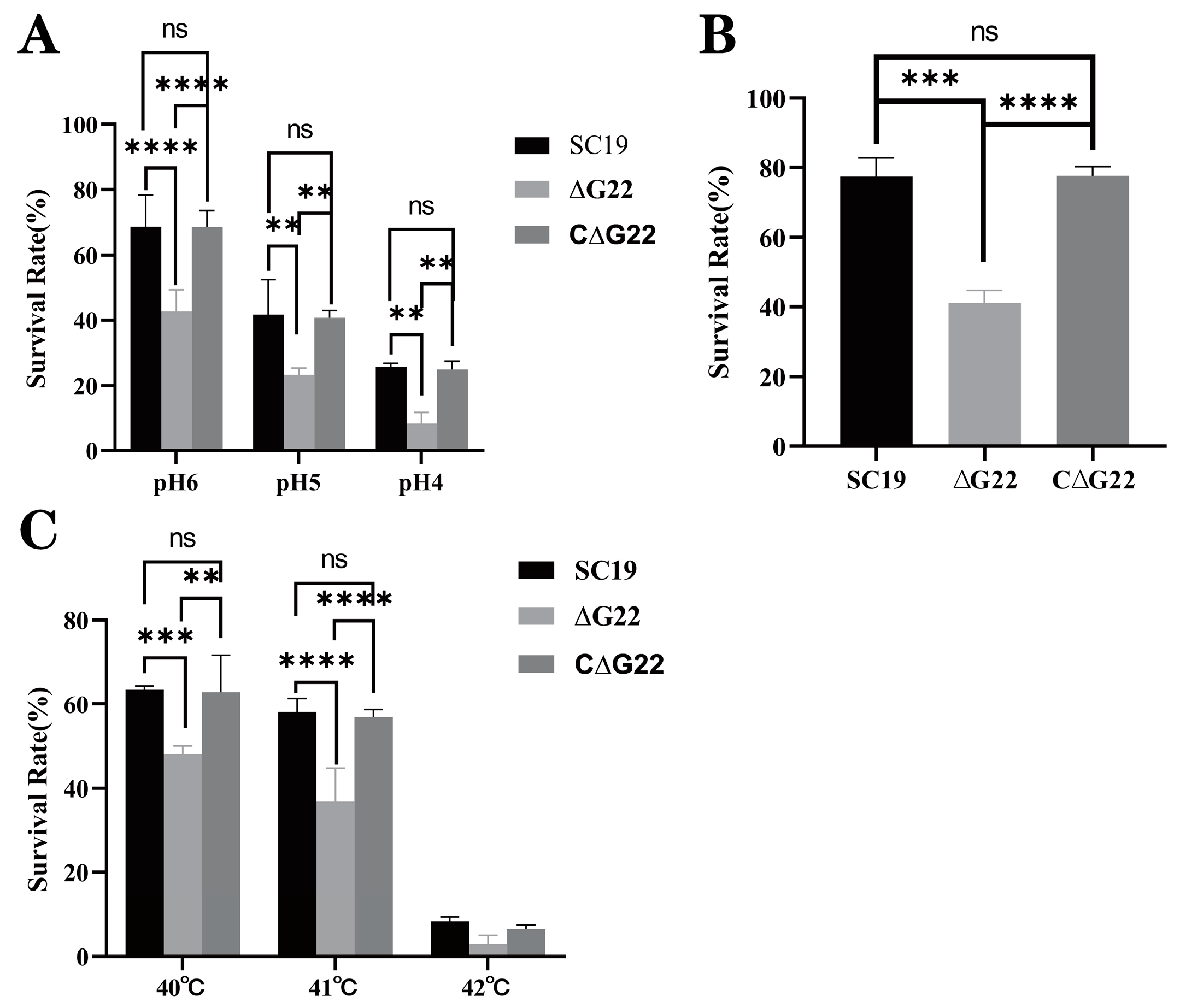

2.6. Experimental Infection of Mice

Overnight cultures of SS2 strains SC19 and ∆G22 were washed twice with PBS and suspended in PBS. Twenty-four 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were randomly divided into three groups, with eight mice in each. They were challenged with 200 µL of PBS containing 5 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU) of SC19 or ∆G22, or with 200 µL of PBS as the blank control. The infected mice were monitored daily for 7 days. The clinical symptoms and deaths were observed and recorded postinfection. Another 18 BALB/c mice were divided into three groups and injected intraperitoneally with 5 × 107 CFU per mouse, to examine the invasion and colonization capacities of SS2 strains SC19 and ∆G22. At 24 h postinfection, the infected mice were killed and brain, blood, spleen, lung, and liver samples were collected. The numbers of colonizing bacteria were measured by plating diluted samples onto TSA containing 10% newborn bovine serum. The present study was carried out in strict adherence to the ethical standards for animal experimentation set forth by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Hubei Academy of Preventive Medicine/Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The experimental protocol was meticulously reviewed and approved by the IACUC, with an assigned ethics approval number 202310190. Throughout the research, we upheld the highest standards of animal care and welfare, ensuring that all procedures were consistent with national and international guidelines on humane treatment of animals. This included the implementation of measures to alleviate pain and distress, such as appropriate use of anesthesia and analgesia, as well as the application of the 3Rs principle—Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement—to optimize scientific rigor while minimizing animal usage.

2.7. Adhesion and Invasion Assays in Caco-2 and HEp-2 Cells

We utilized human laryngeal cancer epithelial cells (HEp-2) and human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (Caco-2) to conduct adhesion and invasion assays of SS2 as described previously, with some modifications[

21]. These two cell lines had previously been used to study interactions with S. suis serotype 2 strains[

9,

28]. These cell lines were purchased from Pricella Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and Warner Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) respectively. Strains were streaked on TSA containing 10% foetal bovine serum and incubated for 16 h on 37 °C. The cultures were then used to inoculate fresh TSB containing 10% newborn bovine serum and cultured overnight. For the adhesion assay, bacterial strains were collected at mid-exponential growth phase (OD600=0.6) via centrifugation and subsequently washed twice with PBS. The bacteria were then resuspended in DMEM culture medium lacking antibiotics to achieve a concentration of 5 × 107 CFU/mL before being added to 24-well tissue culture plates containing HEp-2 and Caco-2 cells. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours. Infected cells were rinsed three times with PBS to remove unbound bacteria. The number of adherent bacteria was determined by plating serial 10-fold dilutions on TSB agar plates and incubating them at 37 °C for 12 hours to count the colonies that had formed. The invasion assay procedure was similar to that of the adhesion assay, with the exception that extracellular and surface bacteria were eliminated using streptomycin (100 ng/mL) and penicillin (100 ng/mL). Each assay was carried out in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

2.8. Anti-phagocytosis Analysis in RAW 264.7 Macrophages

To assess the intracellular survival capacity of bacteria, Murine RAW264.7 macrophages were propagated in DMEM medium fortified with 10% FBS, distributed into 24-well plates at a density of 4×10

5 cells per well, following an adapted protocol from prior literature[

29]. Prior to infection, bacterial cultures in logarithmic phase were harvested by centrifugation, rinsed twice with sterile PBS, and redispersed in fresh DMEM devoid of serum. The macrophages were subsequently challenged with these bacteria at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. Following a 2-hour co-incubation period at 37 ℃ under 5% CO

2 atmosphere, the macrophages were subjected to extensive washing with PBS and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS and antibiotics (streptomycin, 100 ng/mL; penicillin, 100 ng/mL) throughout the experimental duration. To quantify intracellular bacterial survival, infected cells were sampled 2 hours post-antibiotic treatment. After triplicate washes with sterile PBS, the macrophages were lysed using 0.02% Triton X-100 at 37℃ for 15 minutes, thereby releasing the intracellular bacteria. The resultant lysates underwent serial dilutions and were plated onto TSA agar, followed by overnight incubation at 37 ℃. Colony forming units (CFU) were enumerated to ascertain the intracellular bacterial load. To track the dynamics of bacterial survival over time relative to the initial intracellular bacterial count, a relative CFU (rCFU) metric was employed, calculated as the ratio of CFU at a given time point (x) to the CFU at the starting time point (0), adapted from the methodology described by[

30]. This experimental design incorporated three independent biological replicates, each replicated technically in triplicate to ensure robust statistical analysis.

2.9. Whole-Blood Bactericidal Assay

The survival of SS2 in whole blood was determined as described in previous studies (Feng et al., 2016). Briefly, each bacterial suspension was incubated at 37 °C for 5 h under static conditions and then centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 5 min. The pellets were suspended in PBS and the microbial concentrations adjusted to 104 CFU/mL. SC19 (100 µL) or an equal volume of ∆G22 and C∆G22 was added to 900 µL of fresh heparinized pig blood from clinically healthy pigs for 3 h at 37 °C.The initial bacterial volume was set to 100%, and the percentage of remaining bacteria was recorded at this time point (after 3 h). Each assay was performed as three independent biological replicates.

2.10. RNA Sequencing Analysis

The total RNAs of WT and ΔG22 cultures were extracted in late exponential phase with the Total RNA Isolation Kit (Shanghai Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). RNA libraries were constructed and Illumina sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq™ sequencer (Novogene, Beijing, China). The complete genomic sequence of SC19 (accession number: CP020863) was used as the reference genome against which the processed reads from each sample were aligned with Bowtie2. The DESeq R package (1.18.0) was used to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The DEGs were functionally annotated with the NCBI, ENSEMBL, Gene Ontology (GO), UniProt, and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases and a BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) alignment analysis.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.3.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Appropriate statistical tests were selected based on the nature of the data and the experimental design. For normally distributed data with equal variances, one-sample t-tests, or unpaired t-tests was used to compare differences between two groups. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way ANOVA was employed. When data did not meet the assumptions of normality or equal variances, non-parametric tests such as the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test were utilized. For in vivo virulence experiments, survival was analyzed using the LogRank test. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Streptococcus suis is a zoonotic bacterial pathogen that causes lethal infections in pigs and humans[

31]. Among all the

S. suis serotypes, SS2 is regarded as the most important and virulent zoonotic agent, and is responsible for infections in swine and humans[

7]. Therefore, clarifying the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of

S. suis is crucial for the development of novel and effective prophylactic and therapeutic strategies. Although our knowledge of the pathogenesis of

S. suis has improved in recent years, the precise involvement of most of its putative virulence factors remains poorly understood and further studies are required to clarify it[

32].

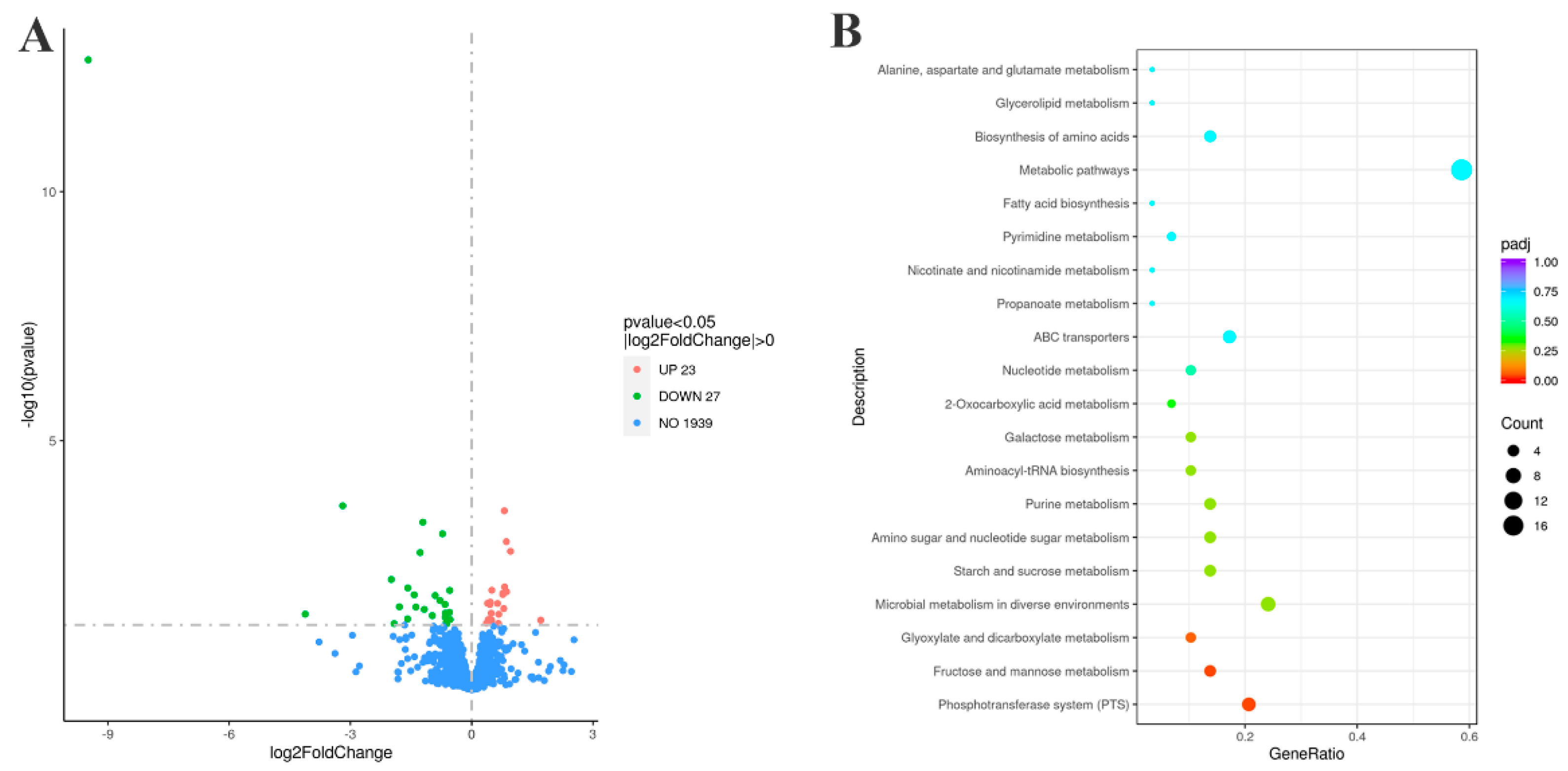

In this study, we investigated the transcriptome-level changes in SC19 in response to the deletion of

G22 to determine how

G22 regulates the high-level pathogenicity of SS2. The deletion of

G22 led to the differential expression of 50 genes, among which several encoded potential virulence-associated factors. The first was involved in the phosphotransferase system.

G22 deletion changed the expression of 14 genes in the PTS, all of which were upregulated, including the four genes

manLMN and

manO and the fructose-specific IIC component

fruA in the mannose-specific PTS. Therefore, we speculate that the deletion of

G22 promoted the phosphorylation of fructose and mannose[

33,

34,

35], thereby indirectly inhibiting the phosphorylation and transport of glucose, inhibiting the expression of virulence factors, and ultimately reducing the virulence of

S. suis SC19. The deletion of

G22 also reduced the expression of

glnA in the two-component system (TCS), which we speculate affected the accumulation of intracellular glutamine in

S. suis, weakening the expression of related virulence factors and ultimately reducing the virulence of

S. suis[

36,

37]. The third virulence-associated system affected was the quorum sensing system (QSS). The loss of

G22 reduced the expression of

lacD in the QSS, which affected the expression of the virulence factor SpeB, also weakening bacterial virulence. Therefore, we investigated whether

G22 is involved in the virulence of SS2[

21,

38] because there is sparse experimental evidence for the biological function of

G22 in SS2 pathogenicity.

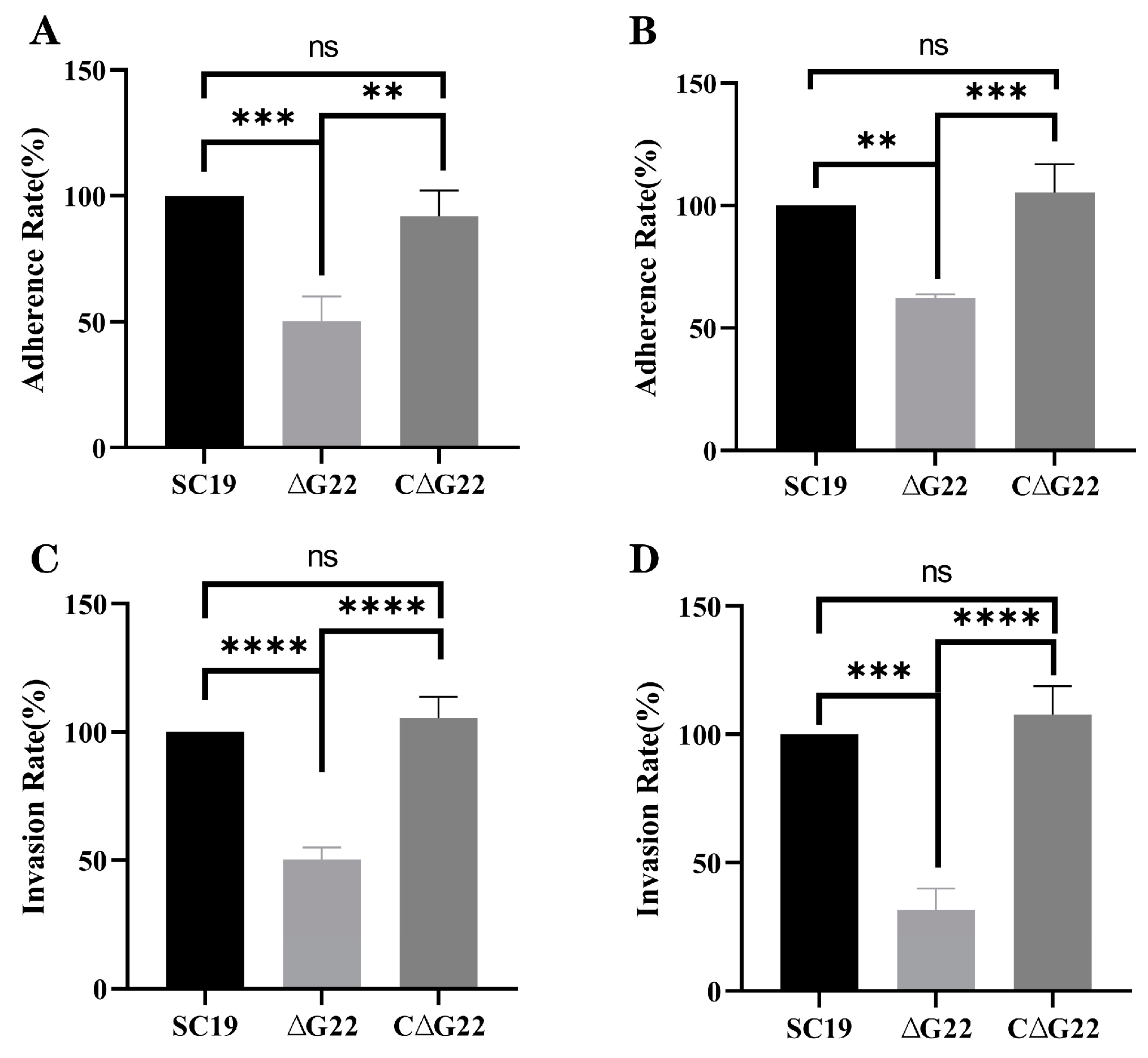

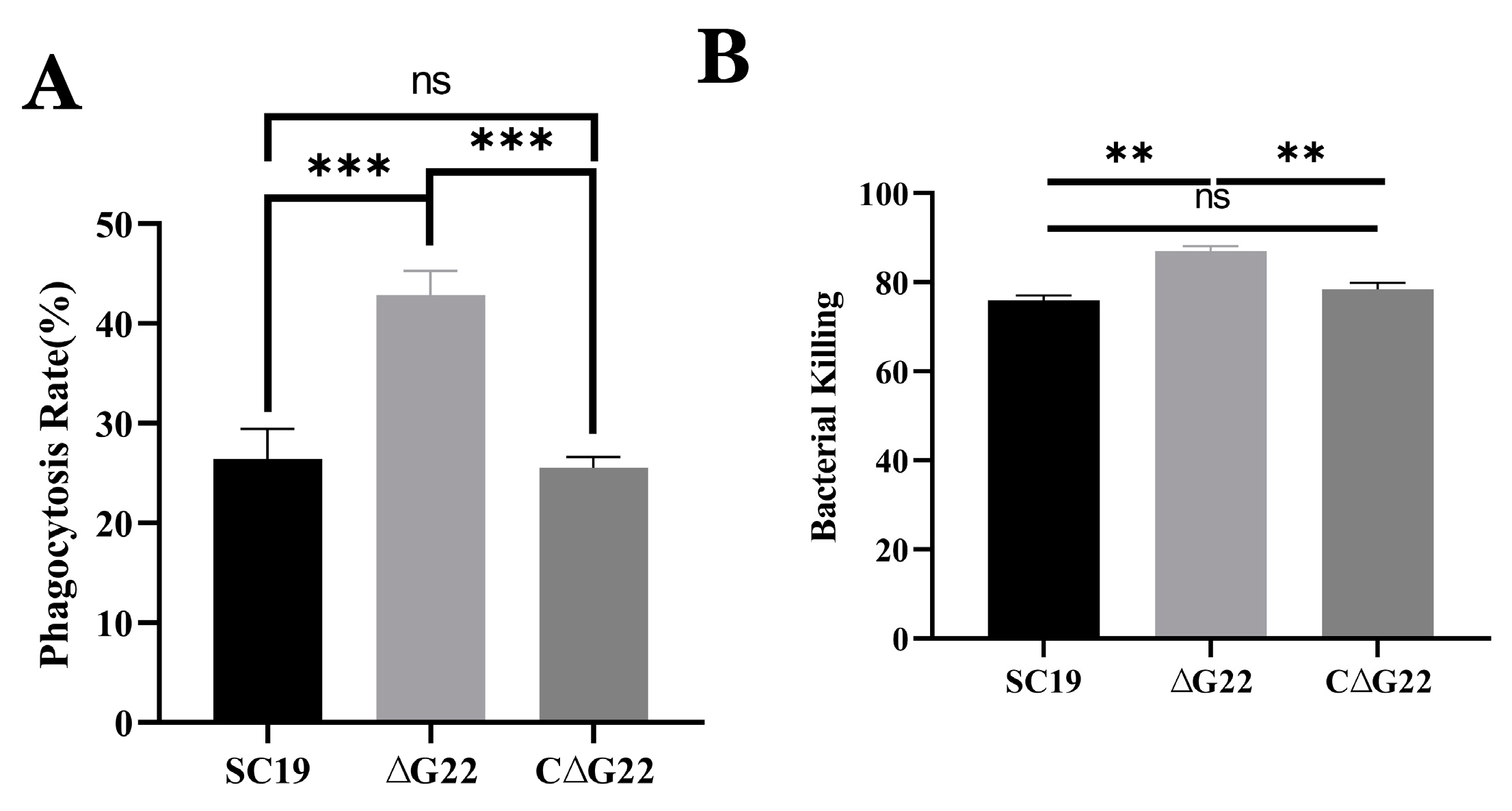

In this study, we defined the phenotypic differences between strains SC19 and ∆G22 to characterize the function of

G22 in terms of the pathogenicity of SS2, to extend our understanding of this zoonotic pathogen. Comparative growth curves showed that the deletion of the

G22 gene had no effect on bacterial growth. However, it reduced the cytotoxicity, adhesion, and invasion of SC19 in Caco-2 and Hep-2 cells, indicating that

G22 contributes to the adhesion to and invasion host cells by SS2.

G22 deletion also rendered the bacterium more easily phagocytosed by RAW 264.7 cells than SC19. In a pig blood resistance assay, ΔG22 was more vulnerable to the bactericidal effect of blood than SC19 and was less viable when exposed to pig blood. The deletion of

G22 reduced the antioxidant capacity and acid resistance of SS2. The

G22 protein mediates SS2 infection by affecting bacterial invasion, phagocytosis resistance, and virulence. This evidence suggests that

G22 is one of the multifunctional factors that play an essential role in the virulence and pathogenesis of SS2. A previous study showed that the

lacD gene is generally distributed in SS2 strains, which encodes a novel metabolism-related factor that contributes to stress tolerance, antimicrobial resistance, and virulence modulation, as moonlighting roles in SS2[

21]. As the most important virulence factor of

S. suis, Cps also prevents host phagocytes from phagocytizing and killing the bacterium[

39]. There are several similarities between

G22 and the abovementioned virulence factors. However, the pathogenesis of the

G22 virulence factor requires further investigation in future research.

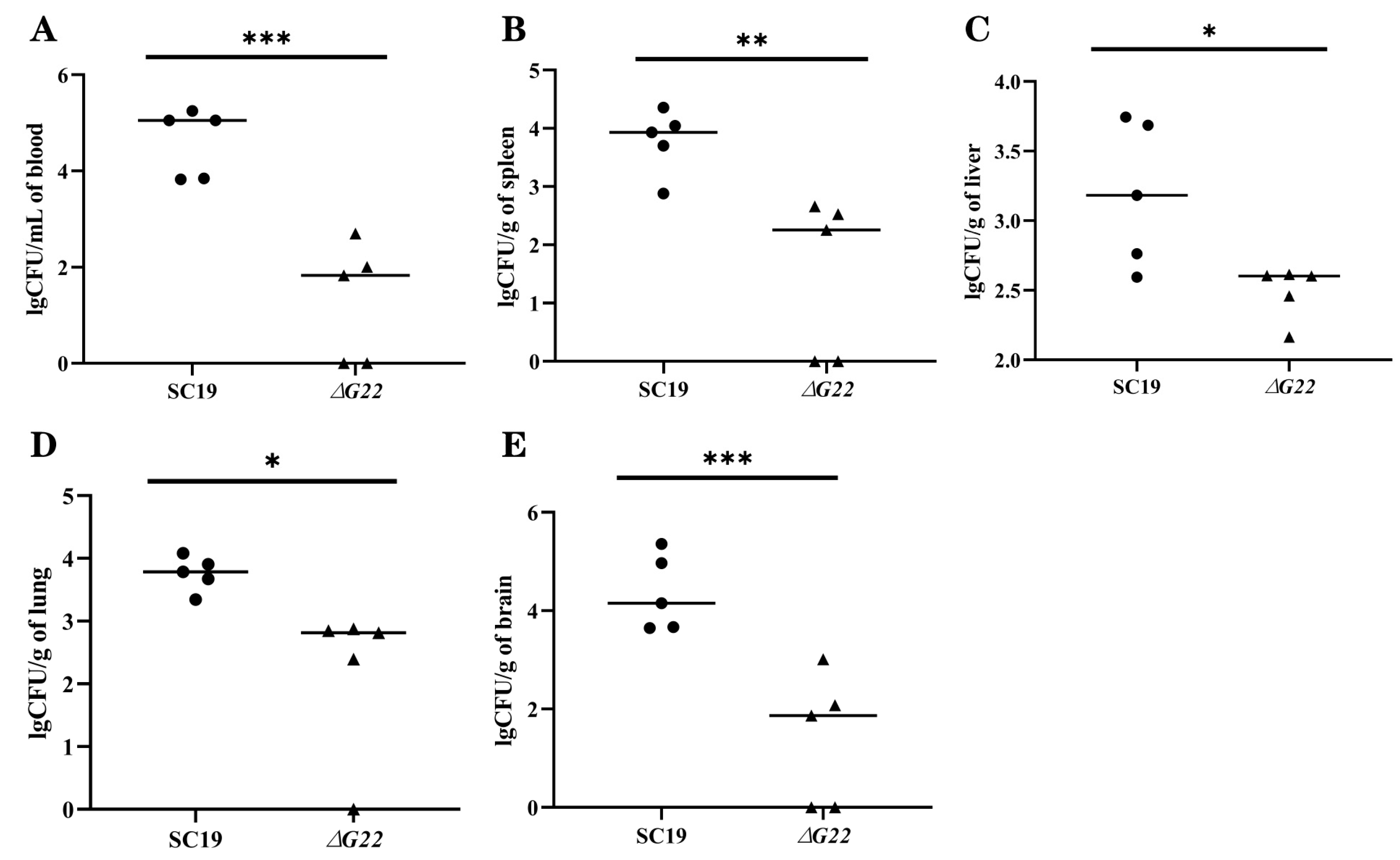

As previously reported, infected mice developed the typical clinical symptoms of

S. suis disease, including septicemia, meningitis, and septic shock, followed by clinical signs of central nervous system(CNS) dysfunction[

40]. We experimentally infected mice to evaluate the inflammatory response of animals infected with strains SC19 and ∆G22. The results indicated that the normal resistance to the bactericidal effect of blood and the BBB-damaging ability of SC19 were significantly reduced in ∆G22 and that the deletion of

G22 increased microbial clearance from the tissues of infected mice. The survival rate of strain ΔG22 in a microenvironment of H2O2-induced oxidative stress was also greatly reduced compared with that of SC19. Consistent with previous findings, the reduced tolerance of ∆G22 for oxidative stress may be an important factor in the reduced survival of the mutant in infected mouse tissues, because ∆G22 is probably less well adapted to the host environment during infection[

26]. This is consistent with our experimental finding that the BBB-damaging ability of ∆G22 was significantly reduced.

The SS2 biofilm structure is complex and may contain lipoprotein, Cps, and host-derived fibrin, although most bacterial biofilms are predominantly composed of a polysaccharide matrix. Extracellular polysaccharides can be categorized into different types based on their apparent morphology: mucin-like protein (also known as ‘mucoid’), which generally creates a resilient outer membrane that adheres to the cell surface through intermolecular hydrogen bonds and other non-covalent bonds, also known as ‘Cps’[

41]. The Cps of SS2 strains is composed of glucose, galactose, N-acetylglucosamine, rhamnose, and sialic acid, which are synthesized by the capsule synthesis clusters[

42]. Transmission electron microscopic analysis of SC19 and ∆G22 showed that ∆G22 had no typical capsular structure, but the Cps structure had become loose and its color had changed to white. This differs from previous reports, in which the capsule of the deletion mutant strain was thinner than that of the WT strain[

42,

43]. Above transcriptomic analysis showed that the deletion of

G22 altered the expression of multiple genes contributing to metabolic pathways, thus indirectly affecting the phosphorylation and transport of glucose. We speculate that this explains the processes underlying these capsule changes. However, these changes warrant further research.

In addition to the findings presented in this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, although mouse models and cell cultures were used to investigate the pathogenicity and virulence of SS2, there may still be differences between these models and natural infections in pigs or humans. Therefore, the results obtained from animal experiments and cell cultures may not fully reflect the actual situation in vivo. Secondly, the study focused on a specific virulent strain, SC19, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other strains or serotypes of S. suis. Future studies should explore the role of the G22 gene in different strains and serotypes to validate the current findings. Thirdly, the pathogenesis of S. suis infections is complex and involves multiple factors. The current study only explored the role of the G22 gene, and other genes and proteins may also play crucial roles in the virulence and pathogenesis of S. suis. Therefore, further research is needed to elucidate the entire pathogenic mechanism.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contri-butions must be provided. The following statements should be used “conceptualization, X.D. and X.C.; methodology, Y.T, S.F., and Z.L.; software, Y.T and S.F.; validation, X.C. and X.D.; for-mal analysis, Y.T and S.F.; investigation, S.F., and X.D.; resources, Y.Z. and X.D.; data curation, Y.T and S.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F.; writing—review and editing, S.F., T.Y., X.C., Z.L., Y.H., Y.F. and J.L.; visualization, Y.T, S.F., and X.D.; supervision, X.D.; project admin-istration, X.D.; funding acquisition, X.D. and X.C.”; All authors have read and agreed to the pub-lished version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Identification of G22 Gene Knockout Strain and Complementary Strain. (A) G22 knockout technology roadmap. (B) Confirmation of the ∆G22 mutant (Lane 1, 3 and 5 were amplified with the external primers W1/W2. Lane 2, 4 and 6 were amplified with the internal primers N1/N2.).

Figure 1.

Identification of G22 Gene Knockout Strain and Complementary Strain. (A) G22 knockout technology roadmap. (B) Confirmation of the ∆G22 mutant (Lane 1, 3 and 5 were amplified with the external primers W1/W2. Lane 2, 4 and 6 were amplified with the internal primers N1/N2.).

Figure 2.

(A) Growth characteristics of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22. Transmission electron micrographs of SC19(B)、∆G22(C) and C∆G22(D).

Figure 2.

(A) Growth characteristics of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22. Transmission electron micrographs of SC19(B)、∆G22(C) and C∆G22(D).

Figure 3.

Survival capacities of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 under stress imposed by acid (A), H2O2 (B), or high temperature (C). Data represent the mean±SEM from at least three independent experiments. ‘ns’,‘**’, ‘***’ and ‘****’ were indicated significant difference values as ‘P > 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001’ , respectively.

Figure 3.

Survival capacities of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 under stress imposed by acid (A), H2O2 (B), or high temperature (C). Data represent the mean±SEM from at least three independent experiments. ‘ns’,‘**’, ‘***’ and ‘****’ were indicated significant difference values as ‘P > 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001’ , respectively.

Figure 5.

Colonization of various tissues of mice by SC19 and ∆G22. (A) Bacterial burdens in the blood of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. (B) Bacterial burdens in spleen tissues of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. (C) Bacterial burdens in liver tissues of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. (D) Bacterial burdens in lung tissues of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. (E) Bacterial burdens in brain tissues of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. Data represent the mean±SEM from at least three independent experiments. ‘*’,‘**’, and ‘***’ were indicated significant difference values as ‘P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

Figure 5.

Colonization of various tissues of mice by SC19 and ∆G22. (A) Bacterial burdens in the blood of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. (B) Bacterial burdens in spleen tissues of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. (C) Bacterial burdens in liver tissues of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. (D) Bacterial burdens in lung tissues of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. (E) Bacterial burdens in brain tissues of BALB/c mice at 24 h postinfection. Data represent the mean±SEM from at least three independent experiments. ‘*’,‘**’, and ‘***’ were indicated significant difference values as ‘P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

Figure 6.

Involvement of G22 in adhesion and invasion of host cells by SS2. (A) Adherence rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in HEp-2 cells. (B) Adherence rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in Caco-2 cells. (C) Invasion rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in HEp-2 cells. (D) Invasion rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in Caco-2 cells. Data represent the mean±SEM from at least three independent experiments. ‘ns’,‘**’, ‘***’ and ‘****’ were indicated significant difference values as ‘P > 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001’ , respectively.

Figure 6.

Involvement of G22 in adhesion and invasion of host cells by SS2. (A) Adherence rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in HEp-2 cells. (B) Adherence rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in Caco-2 cells. (C) Invasion rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in HEp-2 cells. (D) Invasion rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in Caco-2 cells. Data represent the mean±SEM from at least three independent experiments. ‘ns’,‘**’, ‘***’ and ‘****’ were indicated significant difference values as ‘P > 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001’ , respectively.

Figure 7.

Effects of G22 gene deficiency on pathogenicity phenotype of SS2. (A) Phagocytic rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in Raw 264.7 cells. (B) Growth indices of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in pig blood. Data represent the mean±SEM from at least three independent experiments. ‘ns’,‘**’, and‘***’ were indicated significant difference values as ‘P > 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively.

Figure 7.

Effects of G22 gene deficiency on pathogenicity phenotype of SS2. (A) Phagocytic rates of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in Raw 264.7 cells. (B) Growth indices of SC19, ∆G22 and C∆G22 in pig blood. Data represent the mean±SEM from at least three independent experiments. ‘ns’,‘**’, and‘***’ were indicated significant difference values as ‘P > 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively.

Figure 8.

Transcriptomic profiles of strains ∆G22 and SC19. (A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes. (Upregulated genes are shown in red and downregulated genes are shown in green). (B) KEGG metabolic pathways of differentially expressed genes.

Figure 8.

Transcriptomic profiles of strains ∆G22 and SC19. (A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes. (Upregulated genes are shown in red and downregulated genes are shown in green). (B) KEGG metabolic pathways of differentially expressed genes.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or Plasmid |

Characteristics and Functions |

Sources or Reference |

| SC19 |

Virulent strain isolated from the brain of a dead pig; Serotype 2 |

Laboratory collection |

| ∆G22 |

∆G22-deletion mutant strain |

This study |

| C∆G22 |

Complemented strain of G22 ,Spc R, CmR

|

This study |

|

Escherichia coli DH5α |

Cloning host for recombinant vector |

Purchased from Shanghai Sangon Biotech Co., LTD |

| pSET4s |

Temperature-sensitive E. coli-S. suis shuttlevector ,SpcR |

Purchased from Shanghai ke Lei Biological Technology Co., LTD |

| pSET2 |

E.coli-Streptococcus shuttle Cloning vectors; SpcR

|

Laboratory collection |

| pSET4s::G22

|

A recombinant vector with the background of pSET4S, designed to ΔG22, SpcR

|

This study |

| pSET2::G22

|

pSET2 containing the G22 gene and its promoter, SpcR

|

This study |

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

| Primers |

Primers Sequence (5’-3’) |

Functions or PCR Product |

|

G22L-F |

TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCGAAGCAATCTGTCGTGGAGTTG |

Upstream fragment amplification of G22 |

|

G22L-R |

ATTACTATCCACGTTTCATTTTTGAAATATCTCC |

|

G22R-F |

AATGAAACGTGGATAGTAATTCAGTTTTG |

Downstream fragment amplification of G22

|

|

G22R-R |

CTATGACCATGATTACGCCAAGCTTCCACTGTTCTCTATCCATATG |

| W1 |

TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCGAAGCAATCTGTCGTGGAGTTG |

Outside the homologous region identification |

| W2 |

CTATGACCATGATTACGCCAAGCTTCCACTGTTCTCTATCCATATG |

| N1 |

AAGTTGGTCTGTGTGCTATGG |

Internal fragment of G22 identification |

| N2 |

TTAGAACCAGCAGCTCTCG |