Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Work

1.2. Contributions

- Integration of Dual Analysis Techniques: This paper has centralised both the analysis of shared code and shared attributes. The two perspectives on malware connections are established through code comparison using the Jaccard Index and attribute comparison using MinHash. By integrating both file reusability and attribute similarity, it evaluates them more efficiently.

- Advanced Visualization Techniques: This work employs advanced visualization techniques, utilizing Graphviz, to create intricate malware instructional structures. Graphviz’s use of nodes and edges, along with the manipulation of some nodes’ size and colour, enhances the interpretability of the output. This type of visualization surpasses conventional methods by offering a more interactive approach to displaying malware relationships.

- Scalable Similarity Measures: This paper employs the MinHash algorithm to approximate the Jaccard Index at a lower computational cost. This approach helps to make similarity measures more scalable so that analyses based on the malware data will not become unduly large.

- Practical and Dynamic Data Collection: This paper uses public repositories on GitHub to gather up-to-date and diverse malware samples. Also, the ability to watch over these samples with a Shelve database and its query capabilities presents a viable idea of operating with datasets in evolution.

- Comprehensive Malware Detection Framework: This is a detailed and useful framework that merges code and attribute analysis methods. The combination of the two methods improves malware detection, accomplishment, and classification, unlike integrated systems that do not optimally integrate the two methods.

2. Related Theory

2.1. Static Analysis

2.2. Dynamic Analysis

2.3. Jaccard Index

- Parameter Choices: The Jaccard Index compares corresponding sets from malware code, such as extracted strings or byte sequences. Another major factor to be considered is the size of the set – big sets might give more precise values of similarity measures, and, conversely, little sets might give comparisons of a more general type. The string-matching level, such as or , determines when two malware samples are considered equivalent.

- The Jaccard Index is selected as the natural measure as it is for binary or categorical data sets, which is common when analyzing malware where features are present or not presented, for example, API calls. It provides a straightforward yet effective method for assessing the intensity and similarity of two sets, based on the ratio of the intersection set to the union set.

- Handling Different Types of Malwares: The Jaccard Index is utilized to compare two sets of features, like strings or API calls, extracted out of two malware samples. The binary categorization of these features enables the Jaccard Index to measure the similarity between two malware samples in terms of their defining features, even in cases where the malware’s code has undergone mutations or obfuscation.

- Parameter Choices: In SAA, Jaccard Similarity is adopted to address the similarity of sets of attributes for instance API calls. The set size (number of attributes) manages to play a decisive part since a larger set yields a denser comparison. A similarity of is generally used to filter out true positives with fewer chances to involve false positive forms.

- The Jaccard index effectively measures the degree of similarity between two features, such as the type of API call or the system behaviour of two malware specimens and predicts the degree of similarity between these specimens. This makes it particularly suitable for SAA, where we juxtapose sets of attributes that define malware.

- Handling Different Types of Malwares: To the author of SAA, Jaccard is suitable to use because of the capability to measure its overlap, which is important when comparing the behavioral or functional similarity between the samples where they belong to different families or contain polymorphism.

2.4. MinHash Algorithm

- Parameter Choices: MinHash is selected because it provides a fast way for approximating set similarities. The important factor in this case is the number of hash functions employed to create the MinHash signatures. A larger number of hash functions leads to the improved accuracy of the similarity estimation, but it also increases the computational load. In this case, a moderate number of hash functions is chosen to meet the requirements of desired precision and response time (50-100 hash functions).

- The MinHash algorithm has been found most effective, especially with large data sets and obscured malware examples. In general, malware code obfuscation, or polymorphism, makes its identification and matching toward the deployment strings problematic and variant sensitive. MinHash provides an approximate method that calculates the probability of association between sets of strings or code snippets, without the need for direct matching.

- Handling Different Types of Malwares: SCA reveals that the structure of a malware code can change due to obfuscation, mutation, or polymorphism. MinHash resolves these different data strings by focusing on similar subsets of features, such as API function names or system calls, enabling it to identify similarities in mutated malware, even when the code has undergone numerous transformations.

- Parameter Choices: In SAA, MinHash is used in a similar manner to approximate the overall similarity of sets of attributes associated with different malware (such as API calls, file access, or network traffic, for example). The primary measure used in SAA assesses the relevance by determining the number of hash functions used, typically between 50 and 100, to ensure efficient and accurate computation in similar instance detection.

- MinHash is incorporated into SAA due to its ability to compare large vectors of malware attributes, which may be concealed or transformed. Below is an example of behaviors that a malware sample can display, demonstrating how MinHash can assist in developing a practical, scalable method for analyzing the similarities between these behaviors, while acknowledging that each sample need not be identical.

- Handling Different Types of Malwares: In SAA, features such as file behaviour, system calls, or net operation may be examined. This allows MinHash to calculate the similarity of these attributes across various malware samples, irrespective of their formats, styles, or obfuscations.

2.5. Graphviz

2.6. Limitations of Present Approaches

- MinHash: It is efficient for detecting shared code fragments but struggles to analyze attribute-level similarities.

- Jaccard Index: It measures the similarity of attributes successfully but requires appropriate adaptation towards malware datasets.

- Visualization methods are important but do not use a holistic approach of both coding and attribute assessment.

3. Methodology

3.1. Shared Code Analysis

- Data Collection: In this paper, malware samples from multiple GitHub repositories, which contain several executable files. GitHub Choice does, however, present a selection of malware samples, both from different families and their derivatives.

- Feature Extraction: Extracts the mentioned textual features from each malware sample by invoking the terminal command “strings”, which outputs all unique strings present in the given sample. This utility extracts printable characters from binary files and groups them into sets. This paper derives these characters from the strings and analyze them to compare the similarities between them.

-

MinHash Algorithm: The MinHash algorithm is used to calculate the Jaccard Index similarity between two distinct clusters. It generates MinHash signatures and sketches of the malware samples’ attributes. The MinHash technique involves:

- To create minimum hashing signatures, the attributes are hashed using several hash functions.

- The system generates MinHashes and then merges them into sketches, which the database utilizes for similar queries.

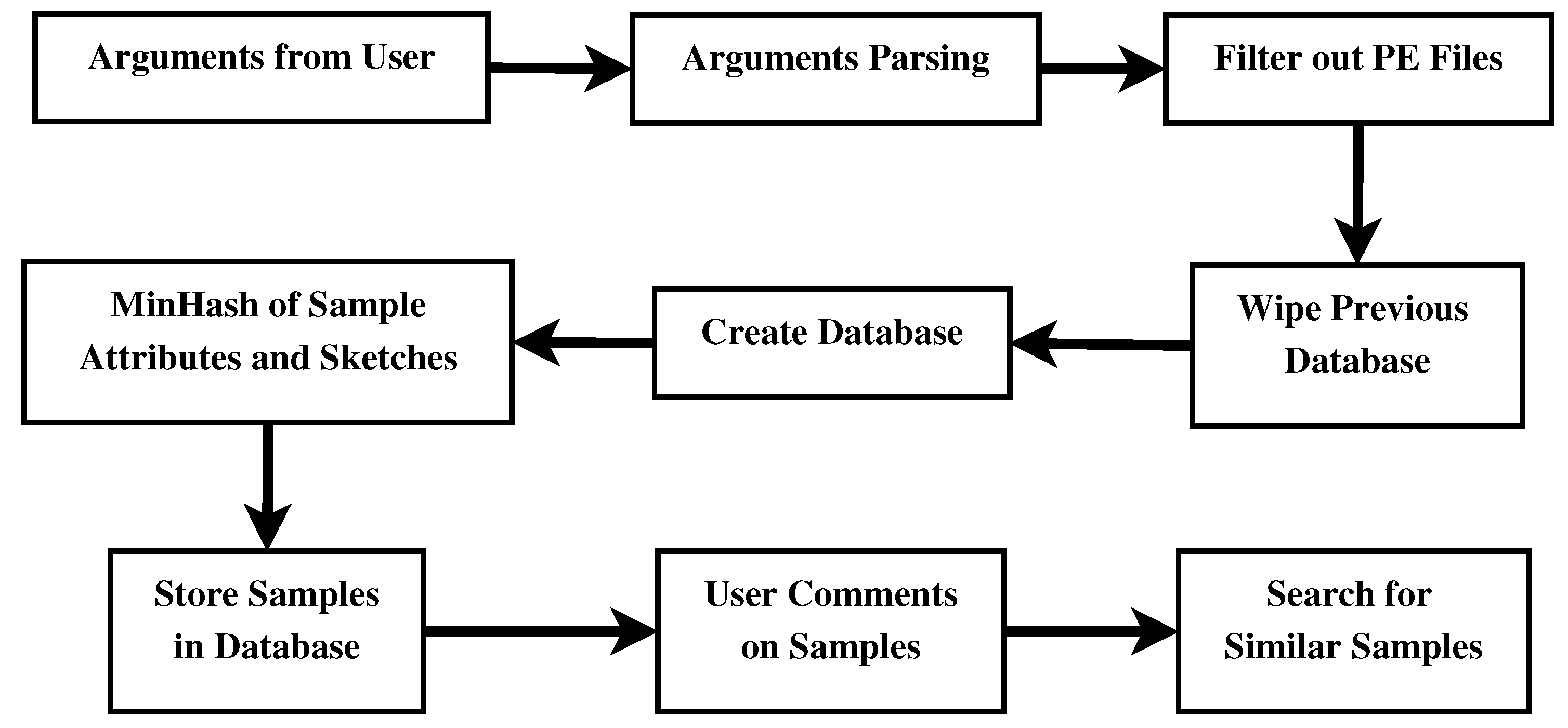

- Arguments from User: It enters the script, reading command-line arguments, and input from the user.

- Arguments Parsing: It parses a command-line argument to determine the path for malware-associated files, the database operations to be performed, and the search parameters to be utilized. It allows one to set it up to run different processes depending on the intended use.

- Filter out PE Files: It ensures the analysis of only Windows Portable Executable (PE) files with the correct header signature, while discarding the relevant files.

- Wipe Previous Database: If necessary, the script erases the existing database to eliminate the impact of previous data on the analysis.

- Create Database: The microcontroller provides a new data base in which to store all historical details about each sample of malware, as well as its attributes and hash values.

- MinHash of Sample Attributes and Sketches: This creates MinHashes and sketches of the malware attributes to try and find other samples that are like a given one.

- Store Samples in Database: The database stores the analysis results and characteristics of malware samples, enabling effective indexing and subsequent use.

- User Comments on Samples: A user can also make comments on specific malware samples and thereby contribute to the database’s development in terms of more observations or experiences.

- Search for Similar Samples: Using MinHashes and sketches, users can specifically locate a given file and categorize it as malware or not, resulting in similarity scores plus comments.

3.2. Shared Attribute Analysis

- Data Collection and Storage: Collection of SCA samples of malware and describe the characteristics of this type of file and then save these attributes in a database along with Jaccard Index and the sketch.

-

Jaccard Index Calculation: The Jaccard Index to gauge how similar the extracted string set is to other malware samples. The most used metrics in Jaccard-based analysis are the size of intersection and the size of union, which measure the similarity between two sets [16].The formula is given by (1) as,A and B represent sets of extracted strings from two distinct malware samples. Therefore, the resulting index ranges from zero to one, a value of zero indicates that cannot compare the two sets under consideration, while a value of one indicates that they are identical [17].

- Database Management: A Shelve database is used to store samples of malware, Jaccard and sketches of the samples. It also enables query search and comparison of samples, as well as ways to store and manage Jaccard and sketches.

-

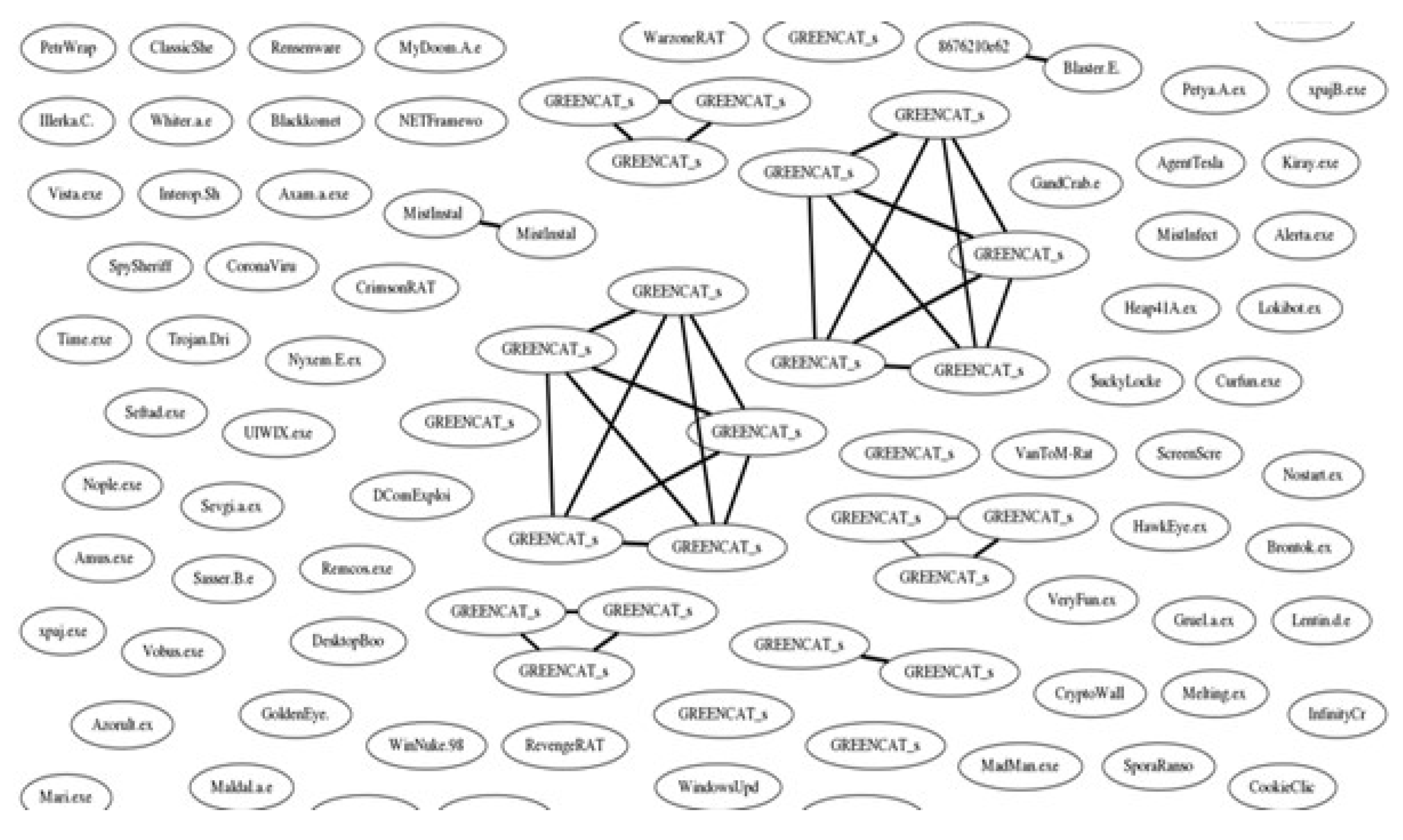

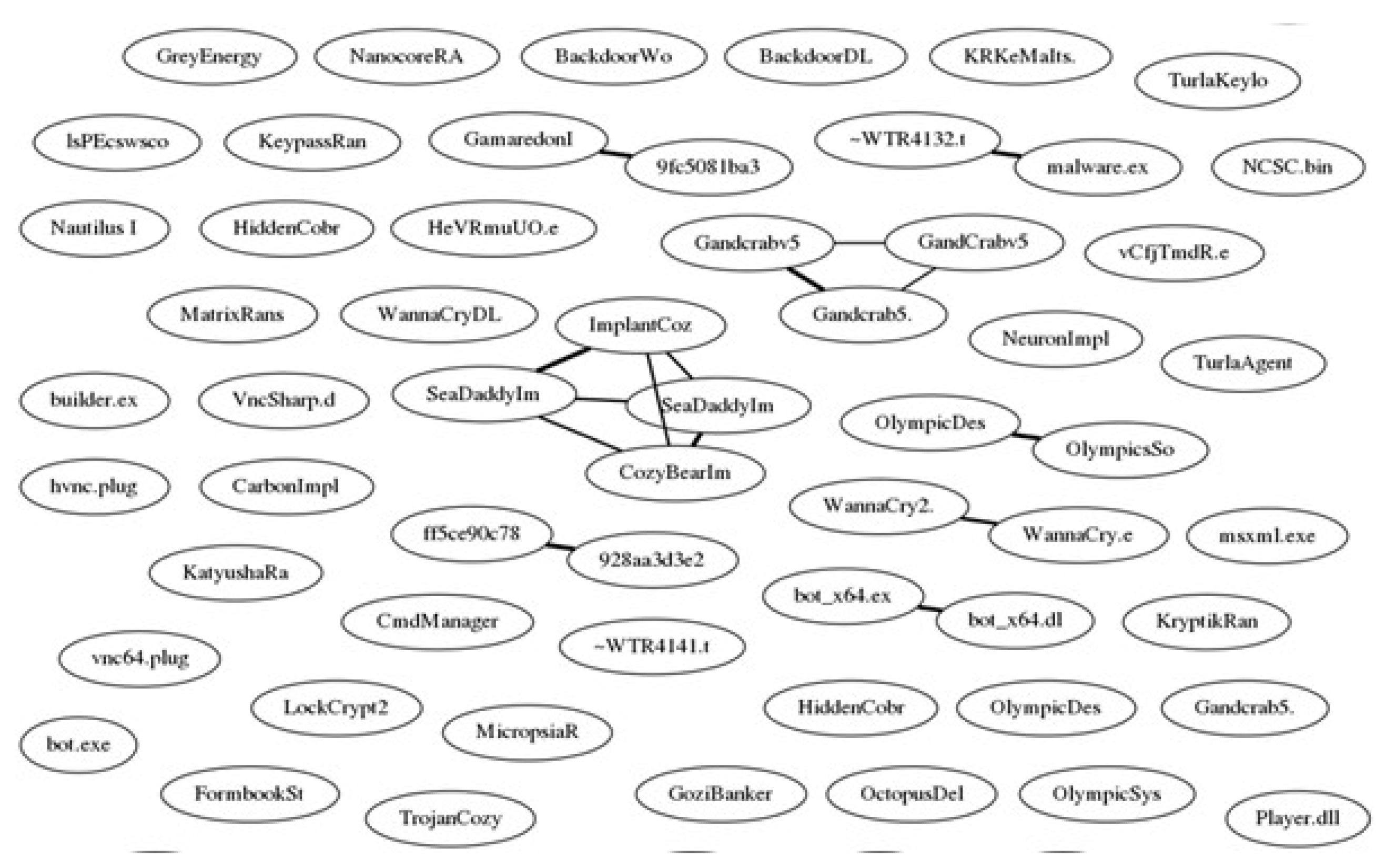

Visualization: The Graphviz tool represents the similarity relationships of malware samples as a graph. They serve as a model for malicious software, where nodes represent samples and edges signify their similarity. They share the visualization output in the form of a PNG image.The specific visualizations created with the help of NetworkX and Graphviz in the current study provide a simple representation of the similarities between the malware samples; the nodes in the figure correspond to the malware samples, and the edges represent their similarities in terms of the attributes, such as the API calls. These visualizations are useful in illustrating the relationships between samples, but they lach the depth required for the instrumentation and categorization of malware for practical applications.

- Limited Analytical Insight: The current graphs primarily highlight the structural connections between various malware samples, without delving into the underlying nature of these relationships. These issues arise when investigating numerous malware program examples, as centrality measures and community detection exceed the capabilities of the available data space.

- Improvement Through Advanced Graph Techniques: Subsequent implementations of the methodology could use community detection algorithms, such as the Louvain method or modularity optimization to isolate clusters of associated malware types. This would empower analysts to make befitting categorization of malware into categories depending on their behavior or functionality. Another way this could be beneficial is by providing more insightful and useful data for decision-making.

- Incorporating Dynamic Attributes: Including dynamic attributes into graphical representations could be a major enhancement. For instance, the escalation of the threat could refer to characteristics like the mutation of the malware, the evolvement of the usage of API calls, or just the alteration of the obfuscation methods that could be traced and illustrated following the evolution of a particular family of the malware. This would assist in gaining insight on malware trends and what new threats are out there that cannot be recognized using the static signature way.

- Interactive Visualization: The graphs could be further enriched with interactivity, where people could explore specific samples of malware, examine and look at detailed descriptions of samples, and consider the selective parameters that would help in calculating the similarities between the samples. More specific search effects, such as mouse-over effects, similarity thresholds, or interactive clustering, would make it easier for analysts to work with the data and make good real-life decisions.

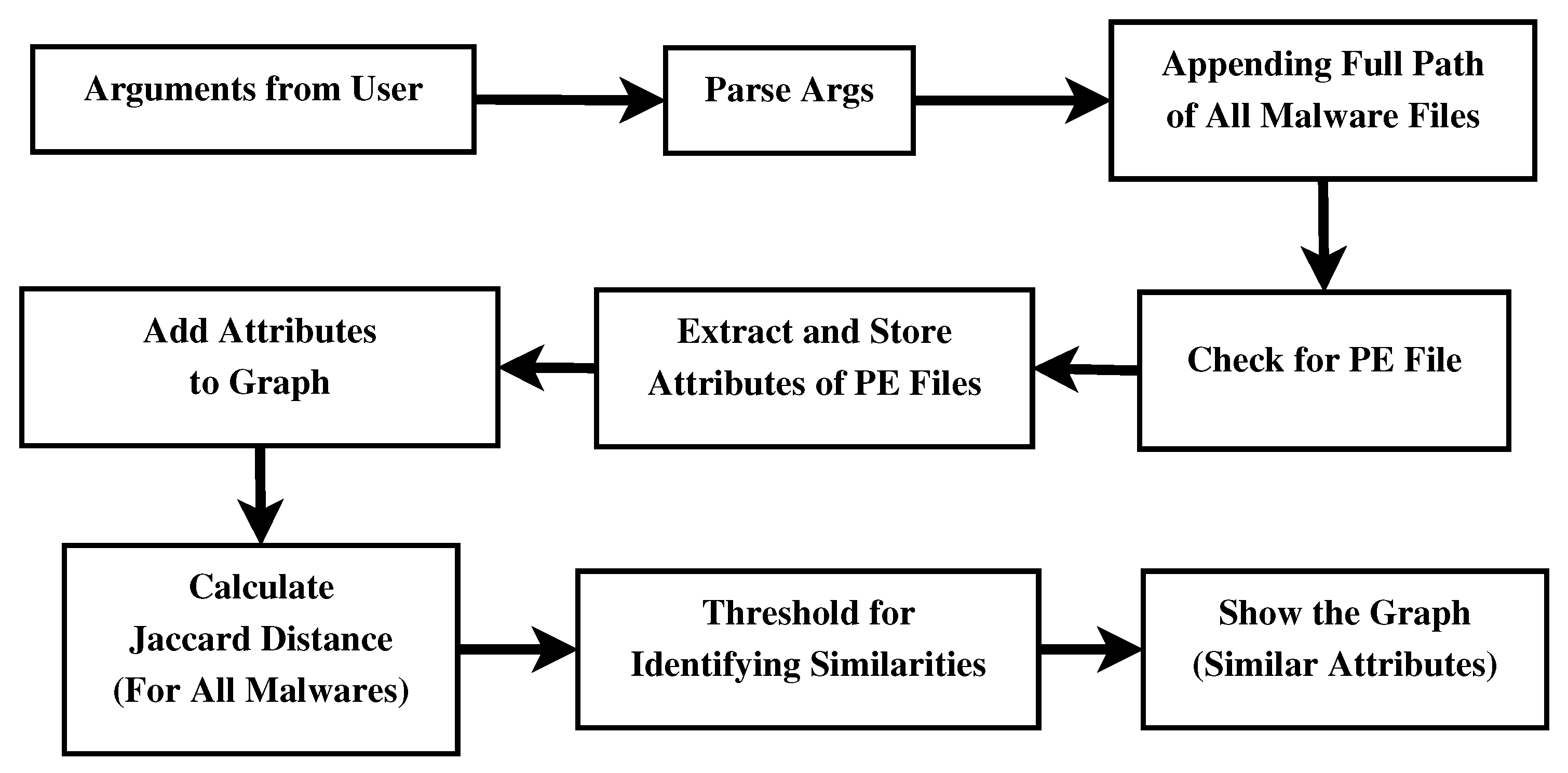

- Arguments from User: The script begins with defining command-line arguments, which may be typed in by a user. These arguments include the directory containing the malware files, the output file for the similarity graph, and the passed similarity threshold between the files.

- Parse Args: They serve to create a script at the command line level and to specify the executive parameters of the task. This means that in source code, only the input and output paths and other features, such as the similarity threshold, remain at the site.

- Appending Full Path of All Malware Files: The script reads and stores in the list the full path of all the malware that exists in the directory mentioned. This guarantees the scanning and subsequent analysis of all files within a directory.

- Check for PE File: To eliminate every non-Windows PE file, the script validates every file using the PE header signature “MZ.” The script only applies additional steps to files with PE headers, ignoring those in other formats.

- Extract and Store Attributes of PE Files: The script extracts strings (attributes of PE files) from each PE file, using a utility string as a guide. Every malware sample in the database has all these attributes gathered and preserved; the combination of strings from all the PE files constitutes this large dataset.

- Add Attributes to Graph: The system generates a similarity graph of attributes based on the features extracted from the sample data. The system relates the graph to the malware samples, awarding points based on the similarity of attributes between two samples.

- Calculate the Jaccard Distance: This tool proves useful when analyzing the three relationships between the attribute sets of different types of malwares. The tool’s purpose is to determine the degree of similarity between the two samples in terms of the characteristics under comparison.

- Threshold for Identifying Similarities: It includes a similarity ratio that determines which malware samples are more similar or belong to the same group. When the Jaccard distance between two samples increases, it indicates a high degree of similarity between them, leading to the creation of an edge in the graph.

- Show the Graph: Lastly, the script computes the similarity graph on the provided corpus, using a tool such as Graphviz. The node data models indicate the sizes of the malicious samples, while the edges illustrate the relationships between the samples and their attributes. The following graph illustrates some of the interrelationships between the different types of malware samples.

3.3. Integration of SCA and SAA

- Complementary Strengths: SCA focuses on the identification of structural similarities concerning detected reusable code fragments of functions and other similar features using MinHash and Jaccard indexes. SAA centres around such similarities in context and behavior as API calls, string patterns, and dependency relations. Integration carries the positive aspects of both techniques and relates the structural and behavioral characteristics of the samples to reveal more profound connections between the malwares.

- Resistance to Obfuscation: Any form of obfuscation, like polymorphism or encryption, often renders dynamic analysis ineffective. Nevertheless, integrating SAA results in the capability of the framework to detect the higher-level behavioral patterns of the subjects and their ability to evade such methods. It is also two-tiered to give cross-checks so that the detection mechanism is immune to manipulation strategies.

- Unified Visualization: The framework utilizes graphing tools, specifically Graphviz, to present relationships based on structural and behavioral analysis. In these visualisations, the nodes are the malware samples, and the edges point to related content found among these samples. The integration makes it possible to detect a malware family, the relationship between different variants, and even similarities between several different families.

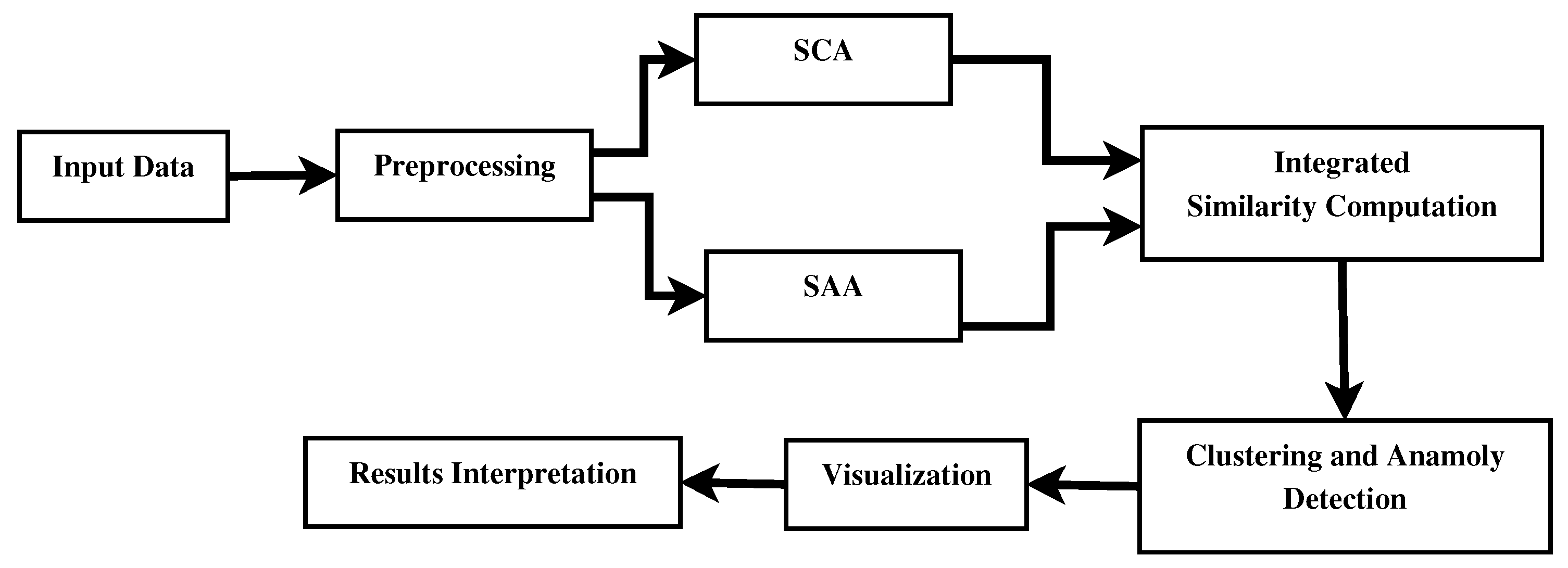

- Data Input Collection: Malware samples include code snippets, attribute metadata like file size and API calls, and description of functionality.

- Preprocessing: Such cleaning and normalization of gathered data are done using tokenizing the code, getting features from metadata, thus making data suitable for further analysis.

-

Dual-Analytical Framework:

- Shared Code Analysis (SCA): MinHash will find structural similarities in code. This would enable very effective detection of shared code fragments in different malware samples.

- Shared Attribute Analysis (SAA): Employ Jaccard Index to impose again, similarity properties this time onto meta-information: file sizes, use of API.

- Integrated Similarity Computation: It combines SCA and SAA scores, which give a unified score regarding the similarity between two samples. The score incorporates the structural and attribute-related characteristics of malware samples.

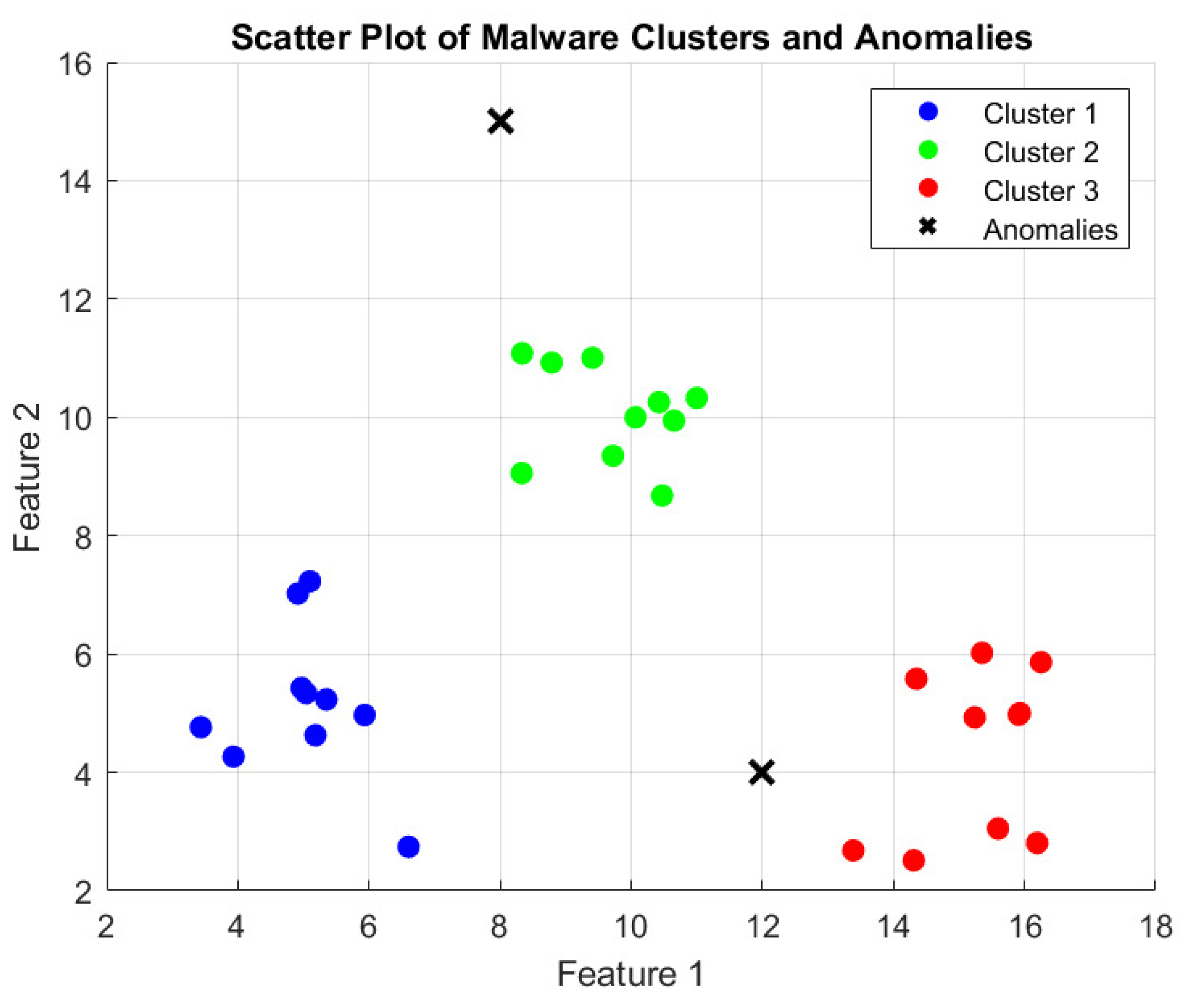

- Clustering and Anomaly Detection: The malware samples are identified as groups of clusters representing malware families, while anomalies representing outliers are marked for future analysis according to the similarity scores.

-

Visualization:

- Scatter Plots: Show groups of malware and outliers.

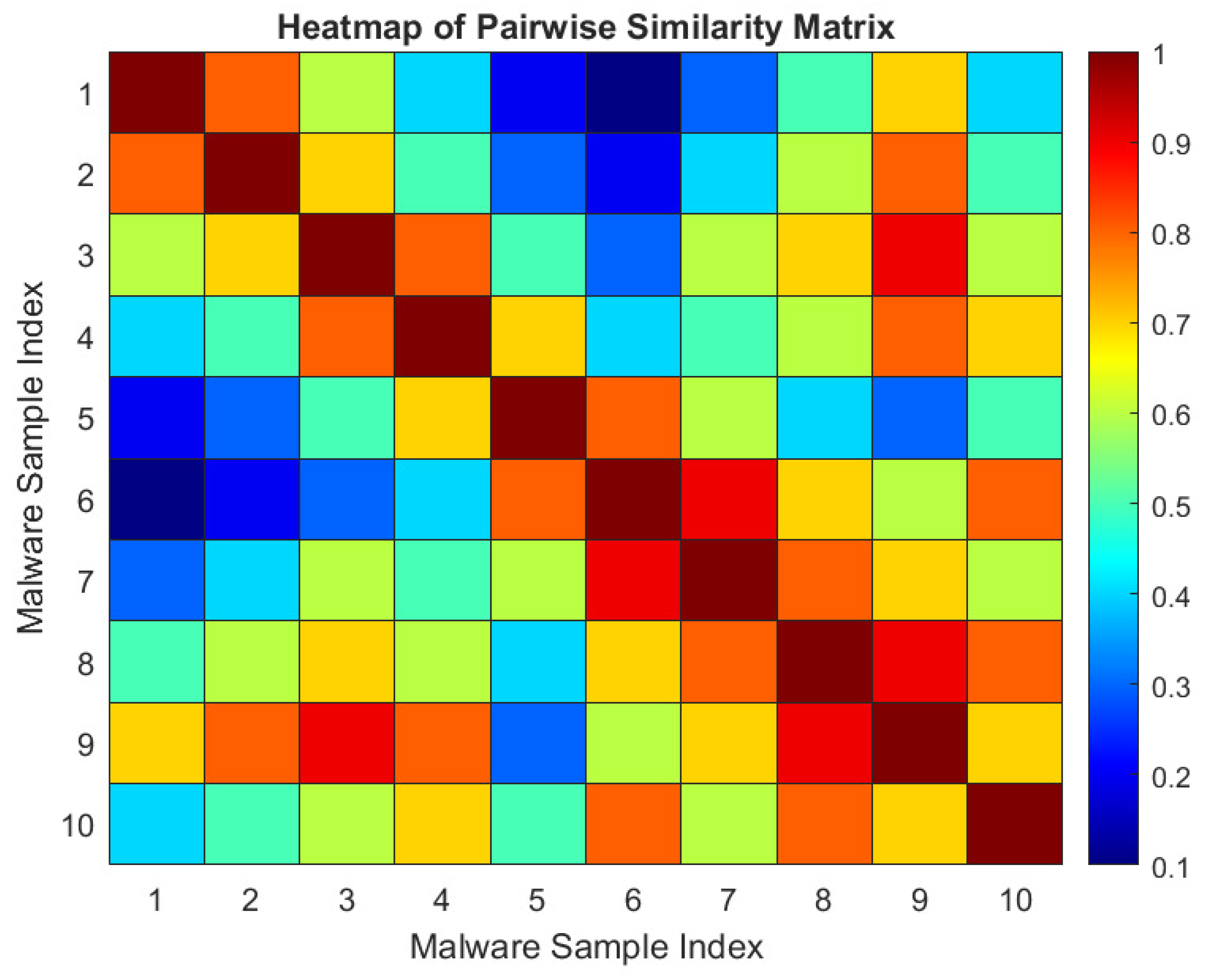

- Heatmaps: It all shows the pairwise relationships of malware samples for an overall view regarding distribution similarity.

- Results Interpretation: Analyzing results to derive actionable intelligence for malware family relationships and patterns with possible threats.

3.4. Threshold Strategies for Effective Malware Detection in SCA and SAA

-

Threshold Choice for Similarity Measurement: In SCA and SAA, similarity thresholds are crucial to identifying between which malware samples are similar. These thresholds are set scientifically and tested empirically to classify the samples of malwares into the right family or variant within families if exist.The commonly used thresholds are:

- -

- 0.6 for all-over relationships for different types of malwares.

- -

- 0.7 is the best test characteristic, offering a better trade-off between false positives and false negatives.

- -

- 0.8 for fine-grained clustering, both within families and within families for similar types of malwares in the case of a large number of similar and similar malwares.

-

Justification for Threshold Selection: The values used for these thresholds have been determined empirically using the discussed equations with the help of the malware samples belonging to various families. Such values, such as 0.7, are said to conform to clustering precision and avoid a high likelihood of mis-grouping contacts.

- -

- Threshold of 0.6: The threshold of 0.6 provides a more general mapping of relationships between various kinds within malware types, making it suitable for detecting families that appear similar at a high level of abstraction but differ significantly at a low level of malware code or behavior.

- -

- Threshold of 0.7: This threshold is optimal for most malware families, as it ensures a true positive rate equal to the recall, while simultaneously minimizing false positives. It forwards consistently without over-learning, which makes it ideal for identifying new samples, which are variants of a basic malware type.

- -

- Threshold of 0.8: The threshold of 0.8 is utilized for other malware types that belong to the same family. This threshold is perfect when you wish to cluster very similar malware samples which only differ slightly.

-

Effectiveness Across Different Malware Families:

- -

- Polymorphic Malware: Over time, the executable’s parts or entire form may change, complicating the classification of such samples. Even when the input matrix is transformed through functions such as MinHash and Jaccard Index, which remove any sense of position related to value occurrence, applying the framework with a coefficient of 0.7 ensures that he polymorphic variants belonging to a particular family are clustered appropriately.

- -

- Cross-Family Detection: We set a similarity of 0 at 0.6 for similar samples from different malware families that may exhibit similar behavior (e.g., spyware or ransomware with a similar function), even though their code may differ.

-

Impact on Robustness: The thresholds play a crucial role in ensuring the robustness of the framework, especially when dealing with:

- -

- Polymorphism: The capability of the malware to evolve in terms of structure but not in terms of its primary function.

- -

- Obfuscation: This is a common practice used by malware programs worldwide to mask their true functions with deceptive ones. They emphasize that even when the code of two variants of a given malware differs substantially, a threshold like 0.7 still allows the framework to identify similarities between obfuscated malware samples.

3.5. Evaluation and Comparison with Existing Tools

- The current evaluation is based on malware samples gathered from GitHub repositories, providing the first clue about how the proposed methodology should work to identify similarities and classify new attachments by family. However, the limited sample size and lack of diversity in malware types hinder the current analysis, making it challenging to apply. This is because there is not enough research on the approach’s resilience and flexibility against various threats.

- In future studies, they need to extend the evaluation protocol to more commonly used malware datasets such as the CICIDS dataset or any other dataset with benchmarked files. This would enable a comparison of the proposed methodology with other malware analysis tools, like VirusTotal, YARA, and signature-based systems, and therefore a systematic comparison of the strengths and limitations.

- The proposed approach is more powerful than the conventional signature-based methods in one aspect, particularly in detecting new or modified URLs belonging to the same group or different from the predefined fingerprint signature. This is especially important for polymorphic or obfuscated malware, which is beyond the capabilities of signature-based detection immune systems.

- Future comparisons should incorporate a greater number of malware sample representatives to enhance accuracy. Apart from evaluating the effectiveness of the methodology, we should also consider other factors like accuracy, false positive and false negative rates, and the duration of the analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Shared Code Analysis Results

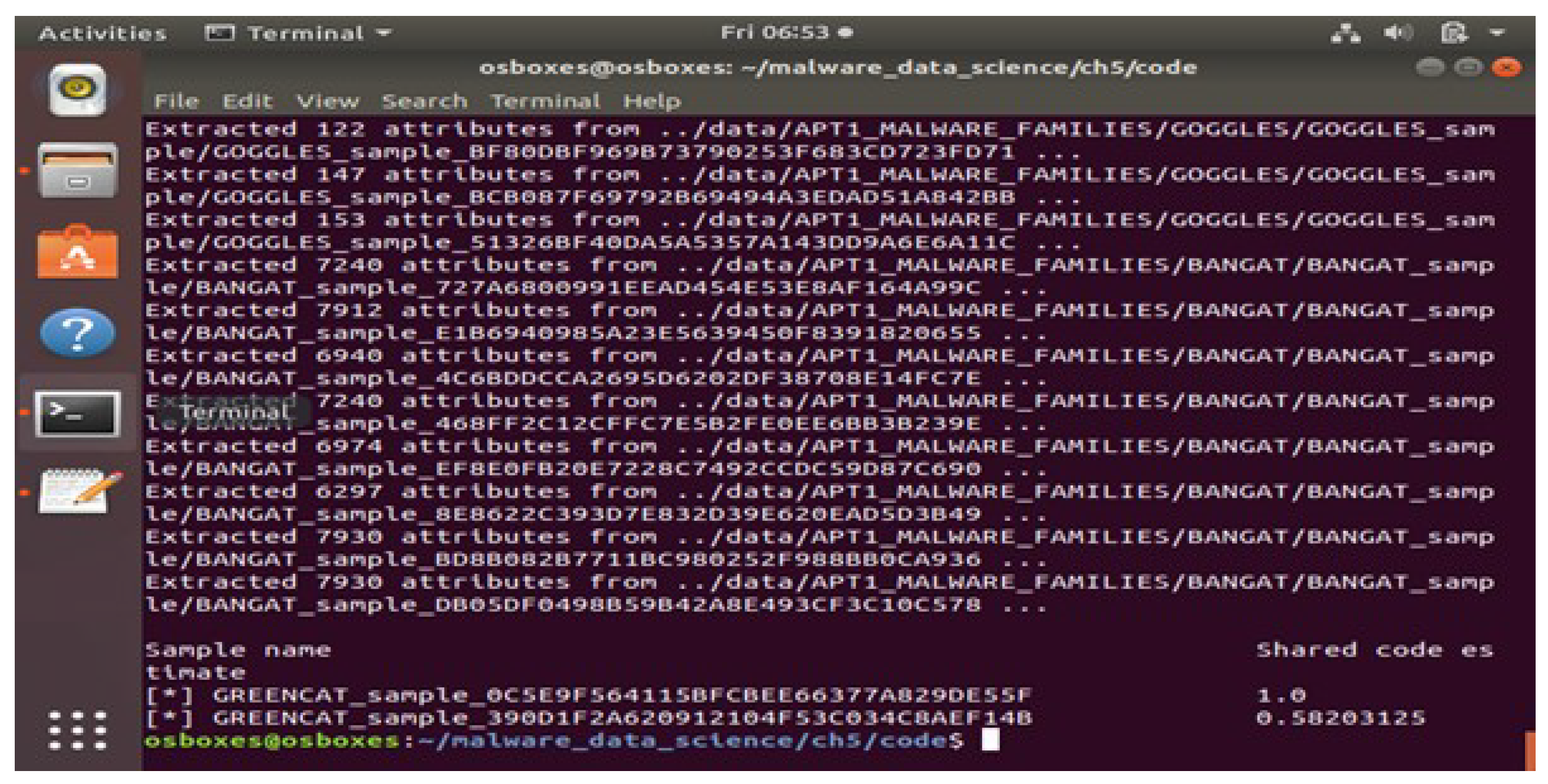

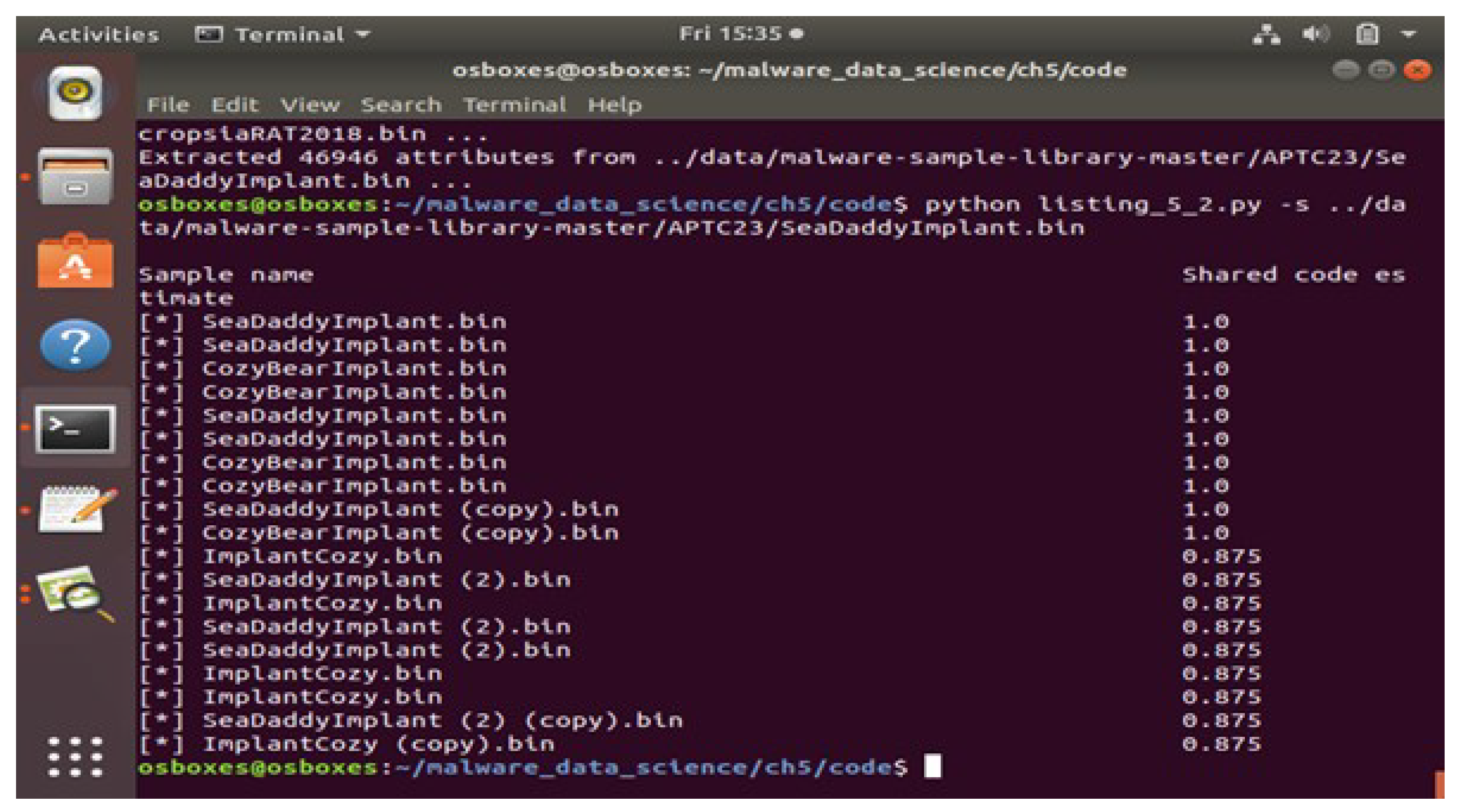

-

python listing_5_2.py- l ../data/Malware_samplesThis command reads all the malware samples in the folder and analyse the code share between the samples.

-

ii. python listing_5_2.py -s ../data/Malware_samplesThis command gives the output in the form of a number which is in between 0 and 1, this implies the percentage of code shared between samples.

4.2. Shared Attribute Analysis Results

- In this paper, coloured and sized the nodes in the graph visualisation based on the calculated similarity scores between them. Bigger nodes with darker colours depict similar samples.

- Small and dense groups of nodes suggest clusters of similar malware samples, where each node is more like nodes in the middle of the cluster.

- Samples with high density (i.e., many edges) are also likely to belong to the same malware family or contain a significant amount of the same code or parameters.

-

python listing_5_1.py ../data/ output.dot fdp -Tpng -o output.png output.dotThe above command listing _5_1.py is the python code for shared attribute analysis which is implemented by giving the path of the Malware samples folder. Here the dot file is converted into PNG image file.

4.3. Visualization of Malware Clusters and Anomalies

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benchadi, D.Y.M.; Batalo, B.; Fukui, K. Efficient malware analysis using subspace-based methods on representative image patterns. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 102492–102507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, H.; Wang, L.; Lv, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Sun, D. DMalNet: Dynamic malware analysis based on API feature engineering and graph learning. Comput. Secur. 2022, 122, 102872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamany, B.; Elsayed, M.S.; Jurcut, A.D.; Abdelbaki, N.; Azer, M.A. A holistic approach to ransomware classification: Leveraging static and dynamic analysis with visualization. Information 2024, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, E.M.; Krisiloff, D.; Coull, S.; Olszewski, D.; Raff, E.; Holt, J. Efficient malware analysis using metric embeddings. Digit. Threats Res. Pract. 2024, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, A.; Gupta, B.B.; Panigrahi, P.K. A comprehensive survey on machine learning approaches for malware detection in IoT-based enterprise information systems. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2023, 17, 2023764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cui, W.; Geng, S.; Bo, B.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, W. A malware detection method of code texture visualization based on an improved faster RCNN combining transfer learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 166630–166641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Yao, C. Malware detection by exploiting deep learning over binary programs. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); IEEE, 2021; pp. 9068–9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, K.; Uda, R. Fast Preprocessing by Suffix Arrays for Managing Byte n-grams to Detect Malware Subspecies by Machine Learning. J. Inf. Process. 2024, 32, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, M.; Sethuraman, S.C. A comprehensive survey on deep learning-based malware detection techniques. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 47, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreopoulos, W.B. Malware detection with sequence-based machine learning and deep learning. Malware Anal. Using Artif. Intell. Deep Learn. 2021, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judy, S.; Khilar, R. Detection and Classification of Malware for Cyber Security using Machine Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2023 Eighth International Conference on Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (ICONSTEM), IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Lad, S.S.; Adamuthe, A.C. Improved deep learning model for static PE files malware detection and classification. Int. J. Comput. Netw. Inf. Secur. 2022, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, M.A. Machine learning techniques for malware detection with challenges and future directions. Int. J. Commun. Netw. Inf. Secur. 2021, 13, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Luo, S.; Pan, L. Byte-Level Function-Associated Method for Malware Detection. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2023, 46, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostock, M.; Heer, J. Protovis: A graphical toolkit for visualization. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2009, 15, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabasakal, İ.; Soyuer, H. A Jaccard similarity-based model to match stakeholders for collaboration in an industry-driven portal. Proceedings 2021, 74, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, B.P.; Shahnawaz, M.; Mohapatra, D.P.; et al. NLP-Driven Malware Classification: A Jaccard Similarity Approach. Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Information Technology, Electronics and Intelligent Communication Systems (ICITEICS) 2024, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Maniriho, P.; Mahmood, A.N.; Chowdhury, M.J.M. A study on malicious software behaviour analysis and detection techniques: Taxonomy, current trends and challenges. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 130, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.; Nguyen, V.H.; Shone, N. Using deep graph learning to improve dynamic analysis-based malware detection in PE files. J. Comput. Virol. Hack. Tech. 2024, 20, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S. Improved consistent sampling, weighted minhash and l1 sketching. Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining 2010, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).