1. Introduction

In the rapidly evolving domain of cybersecurity, the threat landscape is continuously changing, necessitating advanced methods for malware detection. Traditional signature-based detection techniques are struggling to keep pace with the ingenious evasion tactics employed by modern malware, such as polymorphism and metamorphism. This paper endeavors to bridge the gap between the increasing sophistication of malware threats and the current capabilities of detection methodologies. We focus on leveraging Machine Learning (ML) techniques, which show promise in adapting dynamically to evolving malware tactics.

Our research begins by outlining the current cybersecurity threats and the limitations of traditional detection methods. We then introduce a comprehensive taxonomy of ML-based malware detection models, categorizing them into supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning approaches. Each category is examined for its suitability in identifying known and unknown malware types, with a particular emphasis on Supervised Learning methods like Decision Trees, Random Forests, and Neural Networks, as well as Unsupervised Learning techniques such as Clustering and Anomaly Detection.

The core of our study involves a thorough evaluation of these ML algorithms across multiple datasets, assessing their accuracy in detecting malicious code. This paper not only presents a detailed evaluation of various ML techniques in the context of malware detection but also highlights their strengths and limitations in different cybersecurity scenarios. Additionally, we discuss the inherent security concerns associated with implementing ML in malware detection systems, including their susceptibility to adversarial attacks, where malware is deliberately designed to deceive these models. Finally, we address the practical challenges encountered when integrating ML models into real-world cybersecurity infrastructures, focusing on aspects such as scalability and resilience against adversarial attacks. Through this study, we contribute to the ongoing discourse in the field of cybersecurity, offering a forward-looking perspective on the potential of ML to enhance digital defenses against a dynamic and challenging threat landscape.

2. Literature Review

As we dive into the vast field of malware detection, particularly in the context of polymorphic malware and the application of machine learning techniques, we need to discuss current research in detection methods. This literature review aims to explore and generalize key findings and methodologies from existing research, thereby laying a foundation for our study. The focus will be on studies that have addressed the challenges posed by sophisticated malware types, especially polymorphic variants, and the evolution of detection techniques from traditional methods to advanced ML-based approaches.

Using static analysis, Akhtar and Feng were able to generate supervised learning models with over 95% accuracy and under 4% False Positive Rate [

11]. These performance results can be seen in

Table 1. While this approach leads to a higher detection rate, malware authors are becoming more sophisticated with their attacks, having the ability to obfuscate their code. This obfuscation can lead to lower accuracy if the model is not aware of the changes.

Verkerken, D’hooge, et. Al proposed an unsupervised learning method, using four algorithms on two realistic data sets [

12]. While the one-class SVM algorithm performed the best on the individual datasets, achieving an AUROC score of .9705 and .9402, these scores decreased by 30.45% and 25.63% respectively, when the inter-dataset evaluation was introduced [

13].

We see these performance values in

Table 2. This points to the models having limited generalization strength without specific measures or adaptations. Despite the drop in performance, all algorithms still outperformed a random classifier, suggesting a degree of generalization. The one-class SVM showed the least decline in performance. The authors emphasize the importance of focusing on improving model generalization over achieving marginal gains on individual datasets.

The robustness of a machine learning model against adversarial attacks is one of the key focuses in using these models for malware detection. Chen and Bourlai performed experiments regarding the feature modification in malware and how detection compared to baseline [

5].

Table 3 shows the difference in False Negative Rates compared to the maximum evasion cost, δmax, or the cost of manipulating the subset of features in the malware samples. At a δmax = 22, the average number of API calls changed is 12, or approximately 10% of extracted API calls [

14]. This led to a False Negative Rate of almost 70%. Extrapolating to a δmax of 55 led to a False Negative Rate of almost 98%.

Kreuk, Barak, et al. formulated an adversarial example to bypass machine learning models based on modifying bytes in the embedded space Z [

11]. These bytes will be reconstructed to X, preserving the original function of the program but causing the model to predict the file as benign.

“Data: A binary file x, target label y, conv size c

k ← c + (c − len(x) mod c) // k is the payload size

xpayload ∼ U(0, N − 1)k

zpayload, z, ˜zpayload ← M(xpayload), M(x), zpayload

˜znew ← [z; ˜zpayload]

while gθ (˜znew) > 0.5 do

˜zpayload ← ˜zpayload−· sign

(

∇z ¯`∗(˜znew, ˜y; θ)

)

˜znew ← [z; ˜zpayload]

end

for i ← 0 to len(x) do

˜xnew

i ← arg minj d(˜znew

i , Mj )

end

Kruczkowski and Szynkiewicz proposed using Support Vector Machine as a Machine Learning model for malware detection[

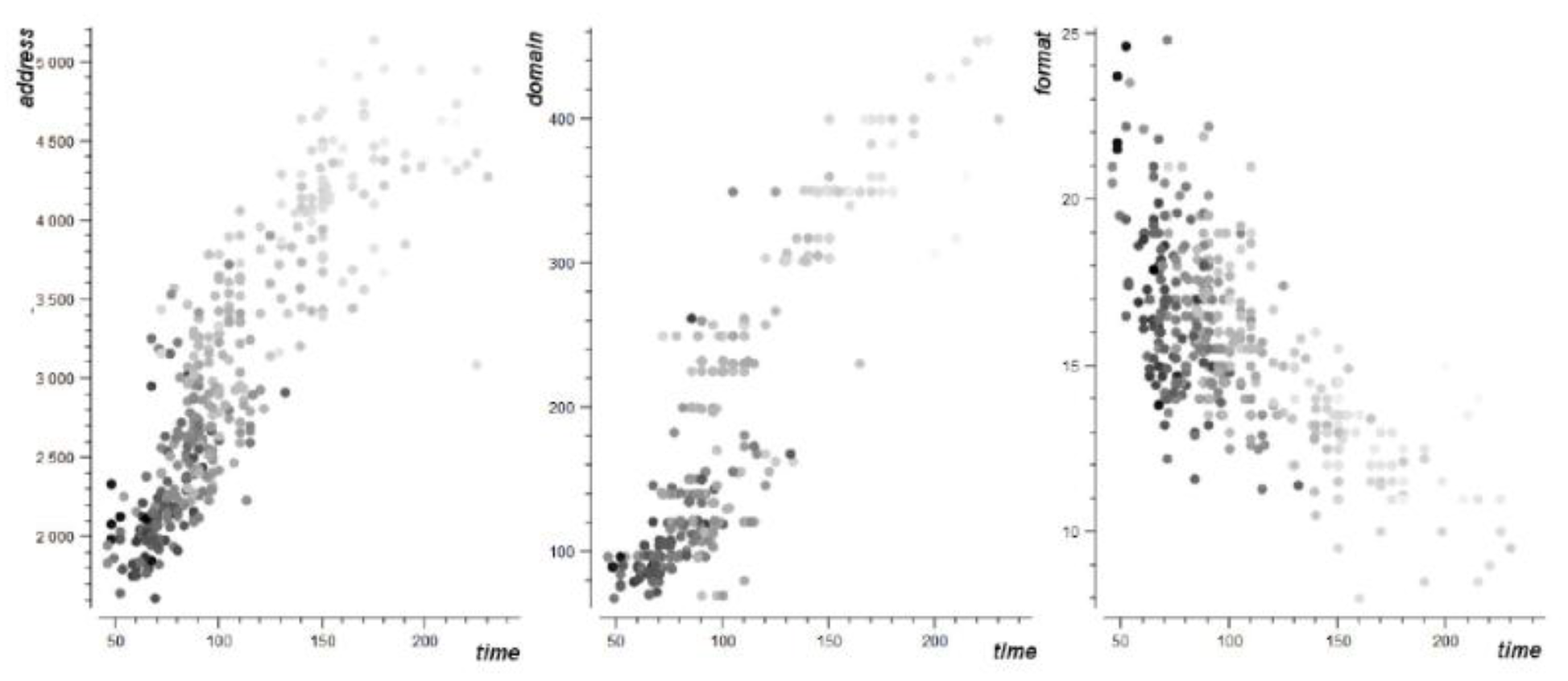

12]. They classified their malware data into two classes: a training set and a test set. Their formula used the time and data the malware sample was added to the N6 database, the domain of the malware, the format of the malware, and the IP address of the malware [

12]. They determined that the correlation between the domain and format of the malware versus the time it was added to the database was positive, while the correlation between the IP address and the time it was added to the database was negative[

12]. Reviewing their research proved contrary to their conclusion. As seen in

Figure 1, their plot showed that the correlation between address and time was positive, while the correlation between format and time was negative. This conclusion may have caused further inconclusion with their findings that SVM as a model for malware detection has a high accuracy in classifying malware.

Finally, Dang, Troia, and Stamp use multiple Long-Short Term Memory based models for predicting and classifying malware[

19]. They used LSTM without embedding, LSTM with Embedding, BiLSTM with Embedding, and BiLSTM with Embedding and CNN as their models for experimentation. To create a feature set, they used the opcode of each file[

13]. They sorted these opcodes and used the 30 most frequent opcodes as their classifier. Their greatest accuracy was 94.32% with a small number of unique families to classify using the biLSTM model with embedding and CNN. As the number of families grew with each model, the accuracy of their model decreased. Their final determination is that combining multiple layers of a LSTM model along with CNN can improve accuracy, with the possibility of greater accuracy using different embedding algorithms[

13].

3. Traditional Malware Detection

Malware, or malicious software, is a software threat that actors use to attempt to gain access to or inflict harm upon a system or network. Malware comes in many forms, including viruses, worms, ransomware, and more. From 2019 to 2020, malware attacks against companies increased 358% and ransomware attacks increased 435% [

1]. Not only do these attacks cause damage to the systems and networks of the companies, but there are also monetary damages that come with these attacks. In 2019, Equifax, Inc. agreed to pay

$575 million in a settlement with the Federal Trade Commission, with the potential for that amount to increase to

$700 million. This was due to Equifax failing to update a vulnerable package in their web portal, allowing attackers to move throughout the network and gain access to customer data [

2]. In total, Equifax spent over

$1.4 billion dollars on cleanup, including upgrades to security infrastructure. In 2021, Colonial Pipeline was hit with a ransomware attack, forcing the company to shut down over 5,000 miles of oil pipelines to limit the damage caused by this attack. Attackers gained access to the systems from a legacy VPN network and spread their malware throughout the system. In the end, Colonial Pipeline paid

$5 million in bitcoin to the Russian cybercriminal group DarkSide to regain control and bring the pipeline back online [

3].

Traditionally, malware is detected by one of two methods, Signature-based detection or Heuristic-Based detection [

4]. Signature-based detection, commonly employed by antivirus software, involves scanning files for specific signatures. Known malware typically has a unique hash or byte sequence that is contained in the antivirus signature database. This database is regularly updated by cybersecurity experts and organizations to include new malware signatures as they are identified. Anti-virus software or other security solutions scan files, executables, and data streams on a system or network for these signatures. If a piece of code in a file matches a signature in the database, it is flagged as malware. This method is highly effective against known malware types. It can quickly and efficiently identify and neutralize threats for which signatures already exist, making it a reliable tool in standard cybersecurity protocols. This can fall short when facing zero-day attacks since signature-based detection is inherently reactive and cannot identify new, unknown malware until a signature has been created and added to the database. It can also be defeated by code obfuscation, when malware authors alter the appearance of their malware without changing its behavior. Finally, this method is more resource intensive, as the database of malware signatures needs to be constantly maintained and updated as new malware is analyzed and signatures are generated for these new pieces of software. Despite its limitations, signature-based detection remains a fundamental component of many cybersecurity strategies, particularly as a first line of defense against known threats. As malware evolves and becomes more sophisticated, the effectiveness of signature-based detection alone diminishes. This has led to the integration of more advanced techniques, such as heuristic and behavior-based detection, to complement signature-based methods.

Heuristic-Based detection is a more dynamic approach to malware detection compared to the traditional signature-based method. It focuses on identifying potentially harmful software by examining the behavior and characteristics of files, rather than relying solely on known malware signatures. Heuristic-based detection analyzes the behavior of programs. It examines how a file behaves when executed, looking for suspicious activities such as unauthorized network connections, attempts to modify system files, or replicate itself, which are common traits of malware. Heuristic-based detection acts in two phases, learning and monitoring. In the learning phase, the heuristic algorithm learns what normal and abnormal behaviors are. This can involve analyzing known malware to understand malicious patterns or monitoring normal operations to establish a baseline of safe behavior. In the monitoring phase, the system monitors new files and programs against the established patterns. If a file exhibits behavior that is significantly different from the norm or matches known malicious patterns, it is flagged as potentially dangerous. There are several techniques for Heuristic-Based detection, but the main focus is on Static and Dynamic detection [

7]. Static Heuristics analyzes the code of a program without executing it, looking for patterns or instructions commonly found in malware. Dynamic Heuristics executes the code in a controlled environment, or sandbox, to observe the behavior of the malware. These indicators are then fed into a detection system to passively scan for malicious activity. Heuristic-based detection can identify new, previously unknown types of malwares as well as adapt to new threats quickly, since it does not depend on a database of known malware to act. This comes with limitations though. Heuristic-Based detection is all dependent on behavior analysis. Legitimate programs can be flagged as malicious due to unusual behavior, leading to an increase in false positives. Malware authors can also implement evasion techniques, mimicking benign behavior, or halting malicious activities when a sandbox environment is detected. Heuristic-based detection is increasingly important in the current landscape of rapidly evolving cyber threats. It is often used in combination with signature-based detection and other methods to provide a more comprehensive defense.

While traditional malware detection methods, such as signature-based and heuristic-based techniques, have been fundamental in identifying and mitigating cyber threats, their effectiveness is increasingly challenged by the sophisticated and evolving nature of modern malware. The limitations inherent in these methods, such as their inability to detect zero-day threats efficiently, high rates of false positives in heuristic approaches, and the constant need for updates in signature-based systems, underscore the need for more advanced and adaptive solutions in malware detection.

This evolving landscape of cyber threats necessitates a change in thinking in our approach to malware detection. As we grapple with the limitations of traditional methods, the focus is now shifting towards more dynamic and intelligent techniques capable of adapting to the ever-changing characteristics of malware. This is where Machine Learning (ML) comes into play. ML offers a promising alternative by leveraging the power of data-driven algorithms to learn from and adapt to new threats in ways that traditional methods cannot.

4. Machine Learning Malware Detection

Machine Learning-based malware detection represents a significant advancement in the field of cybersecurity. Unlike traditional methods that rely on predefined rules and signatures, ML algorithms are designed to learn and evolve, gaining the ability to identify malicious activity based on patterns and anomalies in data. This section dives into how ML is revolutionizing malware detection, discussing various ML techniques, their implementation, and their effectiveness against sophisticated cyber threats. From supervised learning models that classify data based on labeled examples to unsupervised learning that detects anomalies without prior knowledge, ML is setting a new benchmark in the fight against malware.

Supervised Learning is a branch of Machine Learning where the algorithm learns from labeled training data, allowing it to make predictions or decisions [

9]. This approach is instrumental in cybersecurity, especially in malware detection, where it is used to classify data as either benign or malicious based on known characteristics. Supervised Learning requires a dataset that is already labeled. This means having a set of files or network activities that are known to be either safe or malicious. Relevant characteristics of the data are identified and used for training the model. In malware detection, features might include file size, type, behavior patterns, and network traffic characteristics. Various algorithms can be used when working with Supervised Learning, including Decision Trees, Random Forests, and Neural Networks. With sufficient and quality training data, Supervised Learning can achieve high accuracy in detecting known types of malwares. The biggest challenge is the dependency on large volumes of accurately labeled training data, which can be difficult and expensive.

Unsupervised Learning, on the other hand, operates without the need for labeled data, making it particularly valuable in environments where obtaining labeled examples is challenging or impractical [

10]. In cybersecurity, this approach is used to detect malware that may not be identifiable through traditional methods. Unsupervised Learning algorithms analyze and cluster unlabeled data based on patterns or similarities, without prior knowledge of the outcomes or categories. Clustering involves grouping similar data points together, using k-means or hierarchical clustering, while anomaly detection focuses on identifying data points that deviate significantly from the majority of the data. Unsupervised Learning is adept at identifying zero-day threats or malware variants. It does this by detecting anomalies or unusual patterns in network traffic, system logs, or file characteristics, which could indicate the presence of malware. Unsupervised Learning models can also continuously adapt to the changing patterns of normal activity, maintaining their effectiveness even as the nature of network traffic or system use evolves. While Unsupervised Learning has a significant advantage in that it can learn from unlabeled data, it can lead to a higher likelihood of false positives and negatives, as the lack of labeled data can lead to less precise predictions. The lack of labeled data also leads to an increased complexity in interpreting results, as there are no labels or categories for reference. Despite this, Unsupervised Learning excels at early detection of new malware attacks, leading to protection against zero-day threats.

As we have seen, both Supervised and Unsupervised Learning offer unique advantages in the realm of cybersecurity, particularly in detecting new and sophisticated malware threats. However, the effectiveness of these learning models relies on the quality and nature of the data they are trained and operated on. This brings us to a pivotal discussion on the role of data in shaping the efficacy of Machine Learning models in malware detection. What algorithm performs the greatest when detecting malware and what algorithm is most robust when faced with adversarial examples.

5. Research Method and Results

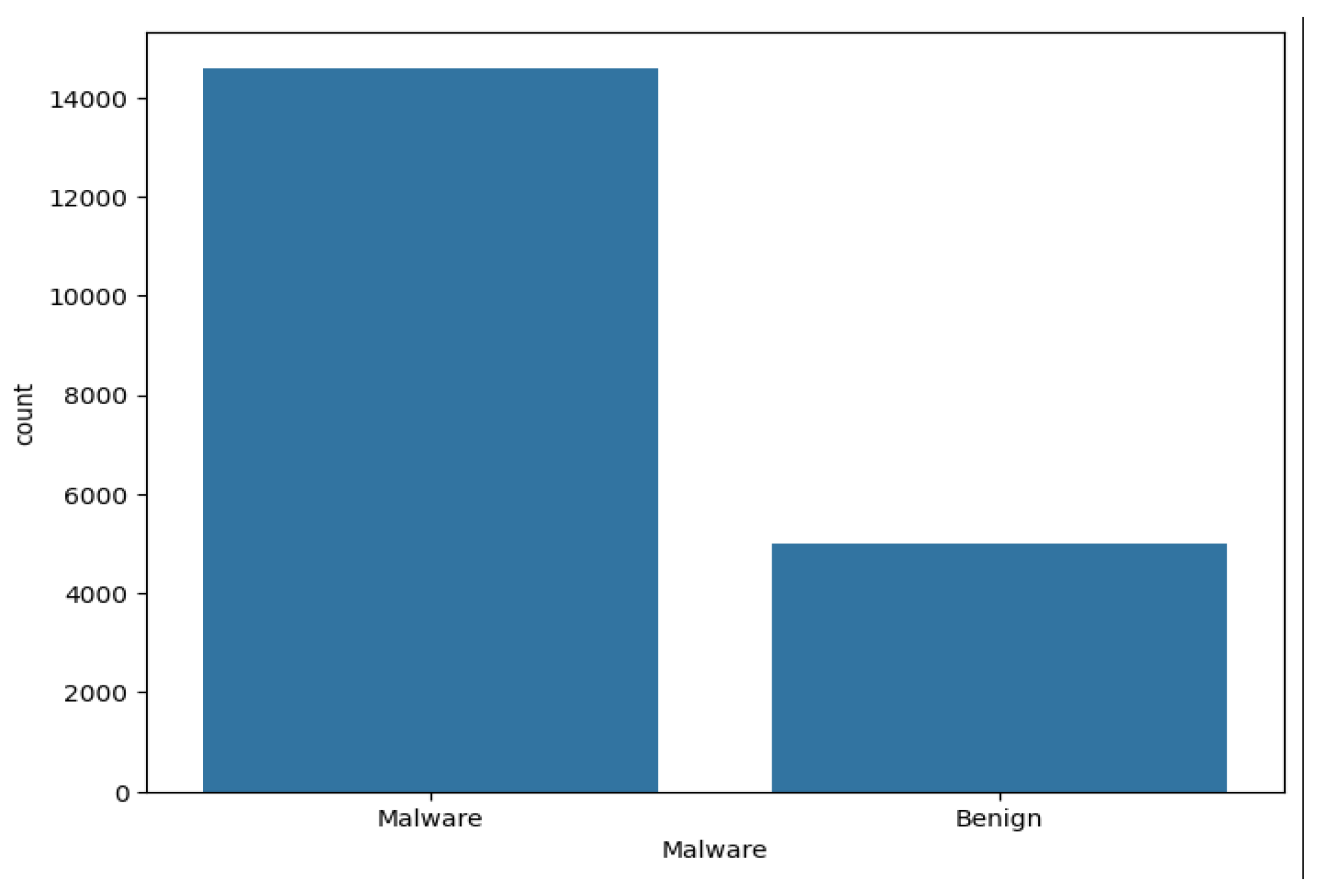

We begin with a benign and malicious dataset from Kaggle [

6]. This dataset contains 19611 entries, 14599 malicious and 5012 benign. We can see this graph breakdown in

Figure 2.

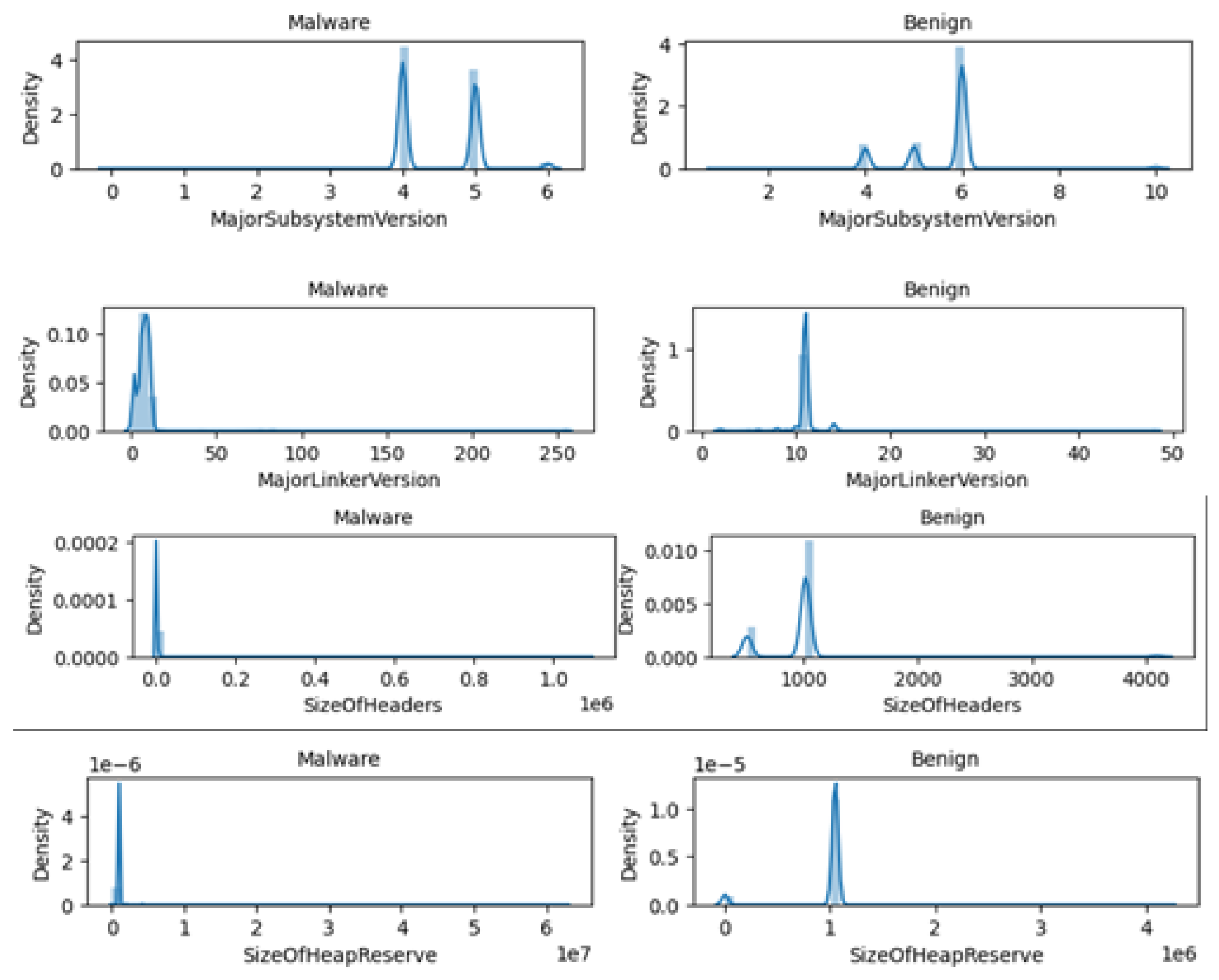

We then use the “seaborn” module in python[

15]. This module contains prebuilt functions to help us parse our data and create plots to determine what feature sets we should use to make predictions. As we see in

Figure 3, some of the features we can make predictions on are “MajorSubsystemVersion”, “MajorLinkerVersion”, “SizeOfHeaders”, “and “SizeOfHeapReserve”.

We can now use the “sklearn” module in python to break down our data set and train our Machine Learning model[

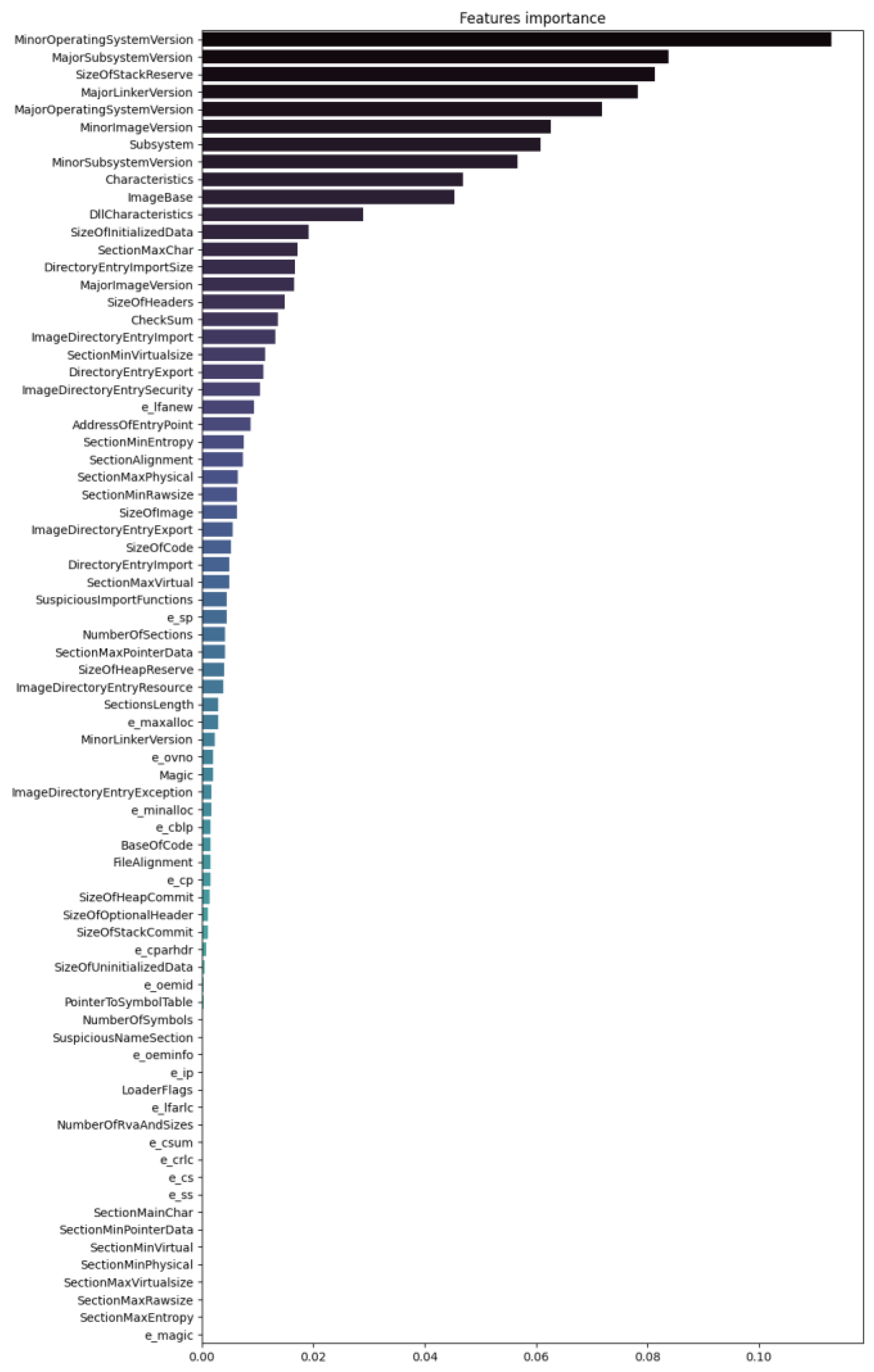

13]. Using the Random Forest Classifier, we train the model on 20% of our data. We train it on all columns except for “Name”, “Machine”, “TimeDateStamp”, and “Malware”. We then test that data against the “Malware” column to determine precision. We can see in

Table 4, our Random Forest Classifier has an accuracy of 99% in identifying Benign and Malicious software.

We can also use the “Feature_importances_” function in “sklearn” to determine how our model ranked the features it learned on. As we can see in

Figure 4, the model gave the most importance to “MinorOperatingSystemVersion”, “MajorSubsystemVersion”, “SizeofStackReserve”, and “MajorLinkerVersion”. While some of the features are ones we used in our prediction, the model favored others.

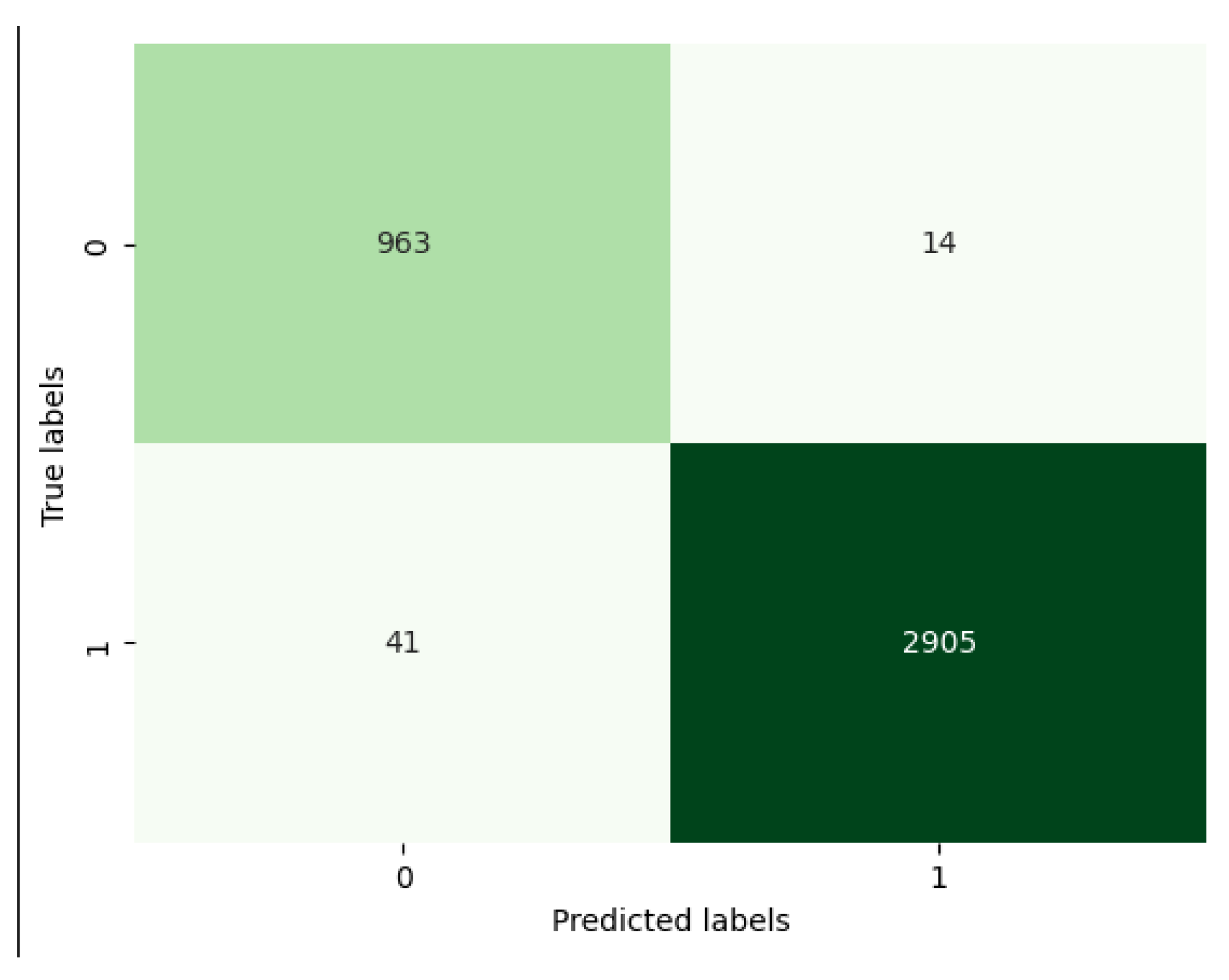

Lastly, we have the prediction labels. As we can see in

Figure 5, the model predicted 2905 inputs as malicious that were actually malicious, 963 inputs as benign that were truly benign, 41 as benign that were actually malicious, and 14 that were predicted as malicious that were truly benign.

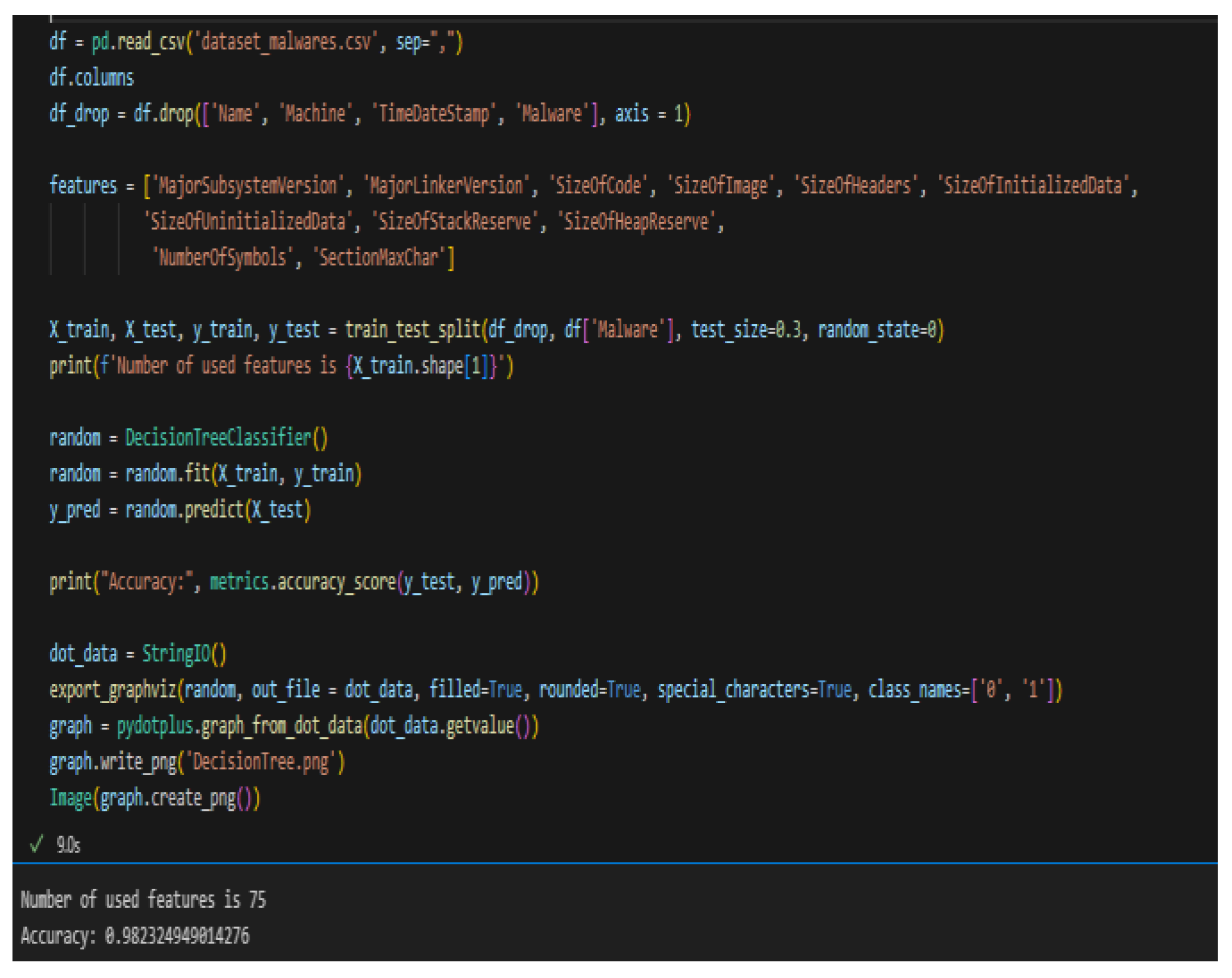

We then take the same dataset and use decision tree learning[

14]. The same “sklearn” module also has prebuilt models for Decision Tree Classifiers. Using the same columns for training and test data, the DT model was trained on 30% of the dataset. As we see in

Figure 6, our model makes a prediction with 98% certainty against 75 features.

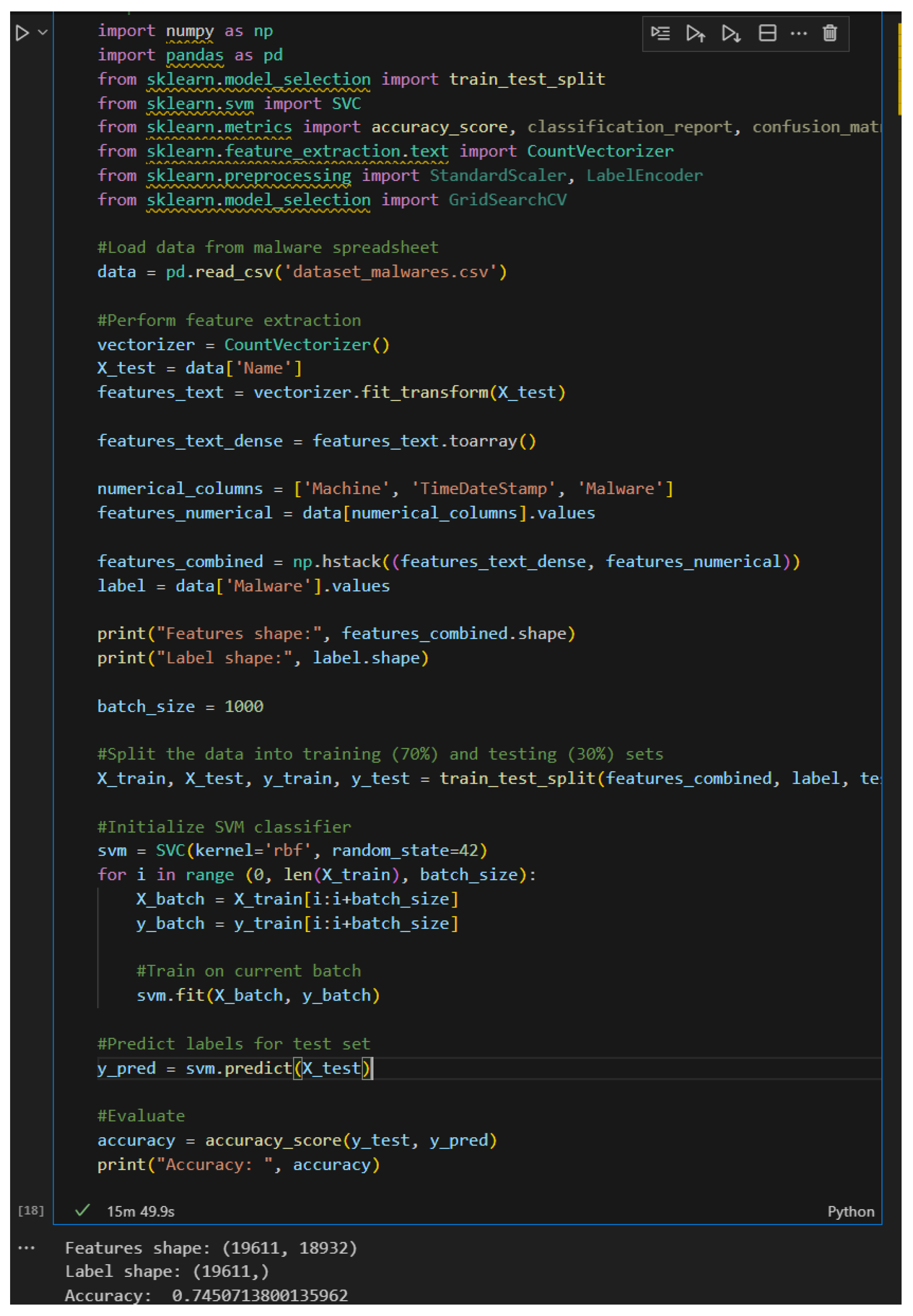

We now take the Support Vector Machine classifier as our model and train it on the same dataset [

14]. We will be using Name, Machine, TimeDateStamp, and Malware as the features. 70% of the data will be used for training and 30% of the data will be the test set. As we see in

Figure 7, this model has an accuracy of 74.5%.

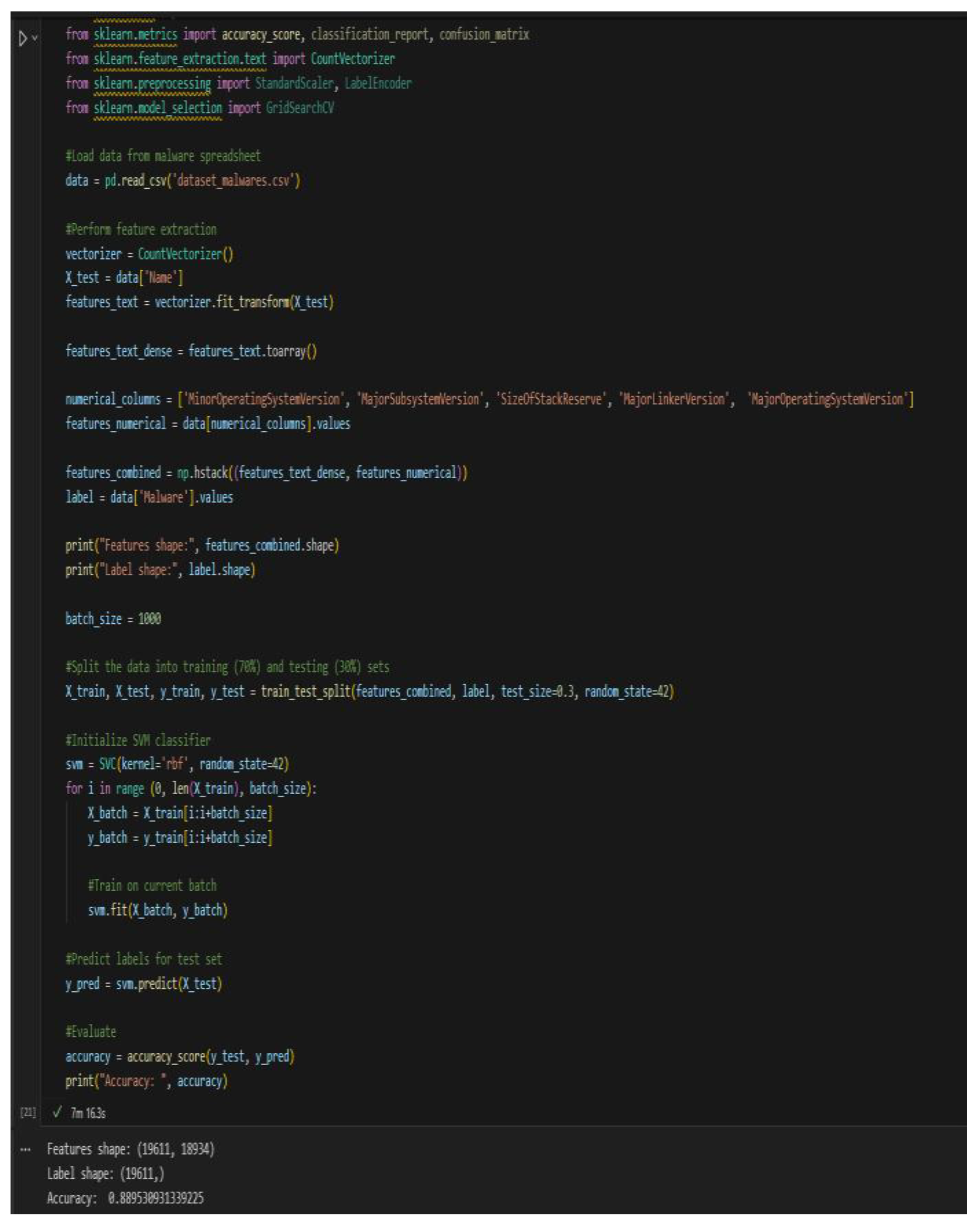

To increase the accuracy of the model, we should be using different columns as the feature set. Looking back at our Random Forest model and the features it listed as most important, we change the features column to use ‘MinorOperatingSystemVersion’, ‘MajorSubsystemVersion, ‘SizeOfStackReserve’, ‘MajorLinkerVersion’, and ‘MajorOperatingSystemVersion’. After running this new code, we see the results in

Figure 8. Not only do we reduce the time it takes to test to 7 minutes, but we also increase the accuracy to 88.9%.

We want to continue to increase the accuracy of the model, so we include more columns for the model to consider. The final features we use for testing are 'MinorOperatingSystemVersion', 'MajorSubsystemVersion', 'SizeOfStackReserve', 'MajorLinkerVersion', 'MajorOperatingSystemVersion', 'SizeOfCode', 'SizeOfImage', 'SizeOfHeaders', 'SizeOfInitializedData', 'SizeOfUninitializedData','SizeOfHeapReserve', 'NumberOfSymbols', and 'SectionMaxChar'. These results are visible in

Figure 9. Using these features, not only does the time climb back up to 15 minutes to run the model, but it also drops the accuracy to 79.3%. We see that the best combination of features to use is in

Figure 8.

The results show that having more features does not improve the accuracy of the model. It was more detrimental to the accuracy and the running time of the model to have more features than choosing the proper features for the model to use. Even so, the Random Forest model was more accurate than the SVM model.

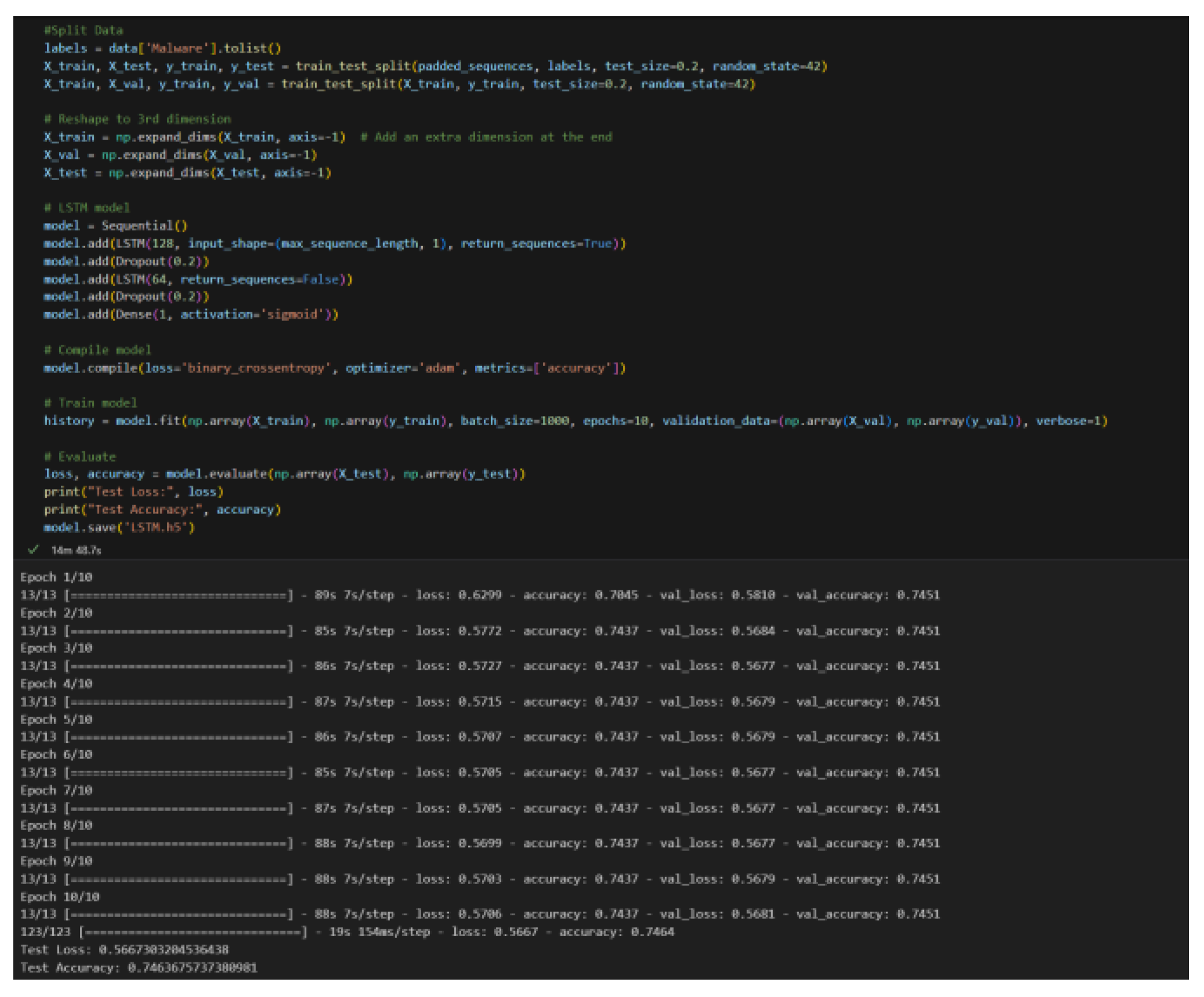

Finaly, we created a Long Short-Term Memory model [

14]. This model is capable of learning long-term dependencies and is used for sequential data analysis, including malware detection. We used the same features as before, “MajorSubsystemVersion’, ‘MajorLinkerVersion’, ‘SizeOfHeaders’, and ‘SizeOfHeapReserve’. As seen in

Figure 10, we see an accuracy of 74.6% and a runtime of 15 minutes.

In our experiment, we showed the accuracy of three machine learning models: Random Forest, Decision Tree, , Support Vector Machine classifier and Long Short-Term Memory. Random Forest had an accuracy of 99%, Decision Tree had an accuracy of 98%, the best accuracy we could get from SVM was 88.9%, and LSTM had an accuracy of 74.6%. This poses the question of complete model accuracy. Are the Random Forest and Decision Tree models that much more accurate than the SVM and LSTM models? Could there be an issue with overfitting causing extensive loss in the model? There is also the possibility that the final two models are too complex for our dataset, causing a decrease in accuracy.

6. Future Work

While our experiment touched on portions of Supervised Machine Learning, we were not able to move on to unsupervised learning due to a lack of knowledge in the implementation of unsupervised modules. Additionally, we were unable to test our models with datasets that had been altered due to adversarial machine learning efforts. Future efforts would involve evolving datasets and other machine learning modules to compare the accuracy and false positive rates. Examples of these future research trends are listed in [15-91].

7. Conclusions

Machine Learning is an ever-growing area of importance in cybersecurity. There is a veritable arms race between malware authors trying to evade detection and machine learning algorithms evolution to be able to adapt to malware obfuscation. Our research covered the traditional malware detection methods, machine learning model algorithms, and some experimentation into malware detection using supervised learning models. The results underscore the potential of ML in cybersecurity, particularly in adapting to and mitigating sophisticated cyber threats. However, they also point to the need for ongoing research, particularly in improving the generalization strength of ML models and enhancing their resistance to adversarial attacks. Future work will focus on expanding the scope to include unsupervised learning approaches and testing models against datasets altered by adversarial machine learning efforts. This continuous evolution in ML methodologies is essential for staying ahead in the ever-changing landscape of cyber threats and ensuring robust digital defenses.

References

- Hartford, "10 Common types of malware attacks and how to prevent them," TechTarget, December 2021. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/searchsecurity/tip/10-common-types-of-malware-attacks-and-how-to-prevent-them.

- J. Fruhlinger, "Equifax data breach FAQ: What happened, who was affected, what was the impact?," CSO, 12 February 2020. Available online: https://www.csoonline.com/article/567833/equifax-data-breach-faq-what-happened-who-was-affected-what-was-the-impact.html.

- C. Wilkie, "Colonial Pipeline paid $5 million ransom one day after cyberattack, CEO tells Senate," CNBC, 8 June 2021. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/06/08/colonial-pipeline-ceo-testifies-on-first-hours-of-ransomware-attack.html.

- Z. Bazrafshan, H. Hashemi, S. M. H. Fard and A. Hamzeh, "A survey on heuristic malware detection techniques," The 5th Conference on Information and Knowledge Technology, Shiraz, Iran, 2013, pp. 113-120. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Ye, Y., & Bourlai, T. (2017). Adversarial Machine Learning in Malware Detection: Arms Race between Evasion Attack and Defense. 2017 European Intelligence and Security Informatics Conference (EISIC). [CrossRef]

- “Benign & Malicious PE Files,”. www.kaggle.com. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/amauricio/pe-files-malwares.

- J. Bergeron, M. Debbabi, J. Desharnais, M. M. Erhioui, and N. Tawbi, “Static detection of malicious code in executable programs.” Int. J. of Req. Eng., 2001.

- M. S. Akhtar and T. Feng, " Malware Analysis and Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms," Symmetry, p. 2304, 2022.

- V. Nasteski, "An Overview of the Supervised Machine Learning Methods," Horizons, pp. 51-62, 2017.

- Verkerken, M., D’hooge, L., Wauters, T. et al. Towards Model Generalization for Intrusion Detection: Unsupervised Machine Learning Techniques. J Netw Syst Manage 30, 12 (2022). [CrossRef]

-

Kreuk, F., Barak, A., Aviv-Reuven, S., Baruch, M., Pinkas, B., & Keshet, J. (2018). Deceiving End-to-End Deep Learning Malware Detectors using Adversarial Examples. arXiv: Learning.

- Kruczkowski, M., & Szynkiewicz, E. N. (2014). Support Vector Machine for Malware Analysis and Classification. 2014 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Joint Conferences on Web Intelligence (WI) and Intelligent Agent Technologies (IAT). [CrossRef]

- D. Dang, F. Di Troia and M. Stamp, "Malware Classification Using Long Short-Term Memory Models," 2021.

- Pedregosa et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python, p. 2825-2830, 2011.

- Waskom, M. L., (2021). seaborn: statistical data visualization. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(60), 3021. [CrossRef]

- Basma Aboelkasem, Quantum Computing Integration in 5G Network and Autonomous Vehicle Systems. October 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kholidy, H.A. Dynamic network slicing orchestration in open 5G networks using multi-criteria decision making and secure federated learning techniques. Cluster Comput 28, 237 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kholidy, Hisham A. "A Novel Blockchain Approach for Continuously Authenticating UAVs to Achieve Zero Trust Principles in 5G-Enabled UAVs." In Nordic e-Infrastructure Collaboration Conference, pp. 1-16. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy, A. Berrouachedi, E. Benkhelifa and R. Jaziri, "Enhancing Security in 5G Networks: A Hybrid Machine Learning Approach for Attack Classification," 2023 20th ACS/IEEE International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), Giza, Egypt, 2023, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy et al., "Secure the 5G and Beyond Networks with Zero Trust and Access Control Systems for Cloud Native Architectures," 2023 20th ACS/IEEE International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), Giza, Egypt, 2023, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- A. Boualem, A. Berrouachedi, M. Ayaida, H. Kholidy and E. Benkhelifa, "A New Hybrid Cipher based on Prime Numbers Generation Complexity: Application in Securing 5G Networks," 2023 20th ACS/IEEE International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), Giza, Egypt, 2023, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Abushgra, H. A. Kholidy, A. Berrouachedi and R. Jaziri, "Innovative Routing Solutions: Centralized Hypercube Routing Among Multiple Clusters in 5G Networks," 2023 20th ACS/IEEE International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), Giza, Egypt, 2023, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy, "A Smart Network Slicing Provisioning Framework for 5G-based IoT Networks," 2023 10th International Conference on Internet of Things: Systems, Management and Security (IOTSMS), San Antonio, TX, USA, 2023, pp. 104-110. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Khalil, M. A. Rahman and H. A. Kholidy, "FAKEY: Fake Hashed Key Attack on Payment Channel Networks," 2023 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS), Orlando, FL, USA, 2023, pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, Fabrizio Baiardi, A. Azab, "A Data-Driven Semi-Global Alignment Technique for Masquerade Detection in Stand-Alone and Cloud Computing Systems", is Submitted in ", granted on January 2019, US 20170019419 A1. https://ppubs.uspto.gov/api/patents/html/20170019419?source=US-PGPUB&requestToken=eyJzdWIiOiJkMjkzNzViZS1mZDY2LTQ5Y2ItOTNkZi1jMTk5NDY0MjQyMTkiLCJ2ZXIiOiI5Y2Y5NTQwMS04MjcyLTRjNjItOTVkNC01NzQ2NDA2ZTA1NTciLCJleHAiOjB9.

- Kholidy; Hesham AbdElazim Ismail Mohamed, “Accelerating Stream Cipher Operations using Single and Grid Systems”, US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), April 2012, US 20120089829 A1. https://ppubs.uspto.gov/api/patents/html/20120089829?source=US-PGPUB&requestToken=eyJzdWIiOiJkMjkzNzViZS1mZDY2LTQ5Y2ItOTNkZi1jMTk5NDY0MjQyMTkiLCJ2ZXIiOiI5Y2Y5NTQwMS04MjcyLTRjNjItOTVkNC01NzQ2NDA2ZTA1NTciLCJleHAiOjB9.

- Hisham Kholidy, “Multi-Layer Attack Graph Analysis in the 5G Edge Network Using a Dynamic Hexagonal Fuzzy Method”, Sensors 2022, 22, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hisham Kholidy, “Detecting impersonation attacks in cloud computing environments using a centric user profiling approach”, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 117, issue 17, Pages 299-320, ISSN 0167-739X, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2020.12.009, April 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hisham Kholidy, “Autonomous Mitigation of Cyber Risks in Cyber-Physical Systems”, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 115, February 2021, Pages 171-187, ISSN 0167-739X. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, “An Intelligent Swarm based Prediction Approach for Predicting Cloud Computing User Resource Needs”, the Computer Communications Journal, Feb 2020. https://authors.elsevier.com/tracking/article/details.do?aid=6085&jid=COMCOM&surname=Kholidy. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, “Correlation Based Sequence Alignment Models for Detecting Masquerades in Cloud Computing”, IET Information Security Journal, DOI: 10.1049/iet-ifs.2019.0409, Sept. 2019. https://digital- library.theiet.org/content/journals/10.1049/iet-ifs.2019.0409. [CrossRef]

- I. Elgarhy, M. M. Badr, M. Mahmoud, M. M. Fouda, M. Alsabaan and Hisham A. Kholidy, "Clustering and Ensemble Based Approach For Securing Electricity Theft Detectors Against Evasion Attacks", in IEEE Access, January 2023. [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi TJ, Rahman AU, Alkahtani HK, Hisham A. Kholidy “Enhancing Object Detection for VIPs Using YOLOv4_Resnet101 and Text-to-Speech Conversion Model”, Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2023; 7(8):77. [CrossRef]

- Alkhowaiter, M.; Hisham A. Kholidy.; Alyami, M.A.; Alghamdi, A.; Zou, C, “Adversarial-Aware Deep Learning System Based on a Secondary Classical Machine Learning Verification Approach”. Sensors 2023, 23, 6287. [CrossRef]

- A Jakaria, M. Rahman, M. Asif, A. Khalil, Hisham Kholidy, M. Anderson, S. Drager, "Trajectory Synthesis for a UAV Swarm Based on Resilient Data Collection Objectives," in IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, Abdelkarim Erradi, “VHDRA: A Vertical and Horizontal Dataset Reduction Approach for Cyber-Physical Power-Aware Intrusion Detection Systems”, SECURITY AND COMMUNICATION NETWORKS Journal, March 7, 2019. vol. 2019, 15 pages. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, Abdelkarim Erradi, Sherif Abdelwahed, Fabrizio Baiardi, "A risk mitigation approach for autonomous cloud intrusion response system", in Journal of Computing, Springer, June 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, Fabrizio Baiardi, Salim Hariri, “DDSGA: A Data-Driven Semi- Global Alignment Approach for Detecting Masquerade Attacks”, in IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hisham Kholidy, H. Hassan, A. M. Sarhan, A. Erradi, and S. Abdelwahed, “QoS Optimization for Cloud Service Composition Based on Economic Model,” Internet of Things. User-Centric IoT, pp. 355–366, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Atta-ur Rahman, Maqsood Mahmud, Tahir Iqbal, Hisham Kholidy, Linah Saraireh, et al “Network anomaly detection in 5G networks”, The Mathematical Modelling of Engineering Problems journal, April 2022, Volume 9, Issue 2, Pages 397-404. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A Kholidy., et al. “A Survey Study For the 5G Emerging Technologies", Acta Scientific Computer Sciences 5.4 (2023): 63-70. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, Fabrizio Baiardi, Salim Hariri, Esraa M. ElHariri, Ahmed M. Youssouf, and Sahar A. Shehata, “A Hierarchical Cloud Intrusion Detection System: Design and Evaluation”, in International Journal on Cloud Computing: Services and Architecture (IJCCSA), November 2012.

- Hisham A. Kholidy, Alghathbar Khaled s., “Adapting and accelerating the Stream Cipher Algorithm RC4 using Ultra Gridsec and HIMAN and use it to secure HIMAN Data”, Journal of Information Assurance and Security (JIAS), vol. 4 (2009)/ issue 4,pp 274,tot.pag 283, 2009. http://www.mirlabs.org/jias/vol4-issue6.html. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, “Towards A Scalable Symmetric Key Cryptographic Scheme: Performance Evaluation and Security Analysis”, IEEE International Conference on Computer Applications & Information Security (ICCAIS), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, May 1-3, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, "A Study for Access Control Flow Analysis With a Proposed Job Analyzer Component based on Stack Inspection Methodology", the 2010 10th International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications (ISDA), pp 1442-1447, Cairo, Egypt, vol. IEEE Catalog: CFP10394-CDR, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hisham Kholidy, “HIMAN-GP: A grid engine portal for controlling access to HIMAN grid middleware with performance evaluation using processes algebra,” 2010 2nd International Conference on Computer Technology and Development, pp. 163–168, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. Bohn, A. Battou, B. Choi, R. Chaparadza, S. Song, T. Zhang, T. Choi, Hisham Kholidy, M. Park, S. Go, “NIST Multi-Domain Knowledge Planes for Service Federation for 5G & Beyond Public Working Group: Applications to Federated Autonomic/Autonomous Networking”, in the IEEE Future Networks World Forum (FNWF), 13–15 November 2023 // Baltimore, MD, USA. [CrossRef]

- I. Elgarhy, A. El-toukhy, M. Badr, M. Mahmoud, M. Fouda, M. Alsabaan, Hisham A. Kholidy, “Secured Cluster-Based Electricity Theft Detectors Against Blackbox Evasion Attacks”, in the IEEE 21st Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), 6-9 January 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Zouzou, E. Benkhelifa, Hisham A. Kholidy and D. W. Dyke, "Multi-Context-aware Trust Management framework in Social Internet of Things (MCTM-SIoT)," 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Communication, Networking and Services (ICCNS), Valencia, Spain, 19-22 June 2023, pp. 99-104. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy et al., “Toward Zero Trust Security IN 5G Open Architecture Network Slices,” MILCOM 2022 - 2022 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), pp. 577–582, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy, A. Karam, J. H. Reed, and Y. Elazzazi, “An Experimental 5G Testbed for Secure Network Slicing Evaluation,” 2022 IEEE Future Networks World Forum (FNWF), pp. 131–138, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy and R. Kamaludeen, “An Innovative Hashgraph-based Federated Learning Approach for Multi Domain 5G Network Protection,” 2022 IEEE Future Networks World Forum (FNWF), pp. 139–146, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy and S. Hariri, “Toward An Experimental Federated 6G Testbed: A Federated Leaning Approach,” 2022 IEEE/ACS 19th International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), pp. 1–6, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hisham Kholidy, Andrew Karam, James L. Sidoran, Mohammad A. Rahman, "5G Core Security in Edge Networks: A Vulnerability Assessment Approach", the 26th IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (The 26th IEEE ISCC), Athens, Greece, September 5-8, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. I. Haque, M. Ashiqur Rahman, D. Chen, Hisham Kholidy, "BIoTA: Control-Aware Attack Analytics for Building Internet of Things," 2021 18th Annual IEEE International Conference on Sensing, Communication, and Networking (IEEE SECON), 2021, pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- S. SH. Haytamy, H. A. Kholidy, and F. A. Omara, “ICSD: Integrated Cloud Services Dataset,” Services – SERVICES 2018, pp. 18–30, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy et al., “Attacks detection in SCADA systems using an improved non-nested generalized exemplars algorithm,” 2017 12th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES), pp. 607–612, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Iannucci, H. A. Kholidy, A. D. Ghimire, R. Jia, S. Abdelwahed, and I. Banicescu, “A Comparison of Graph-Based Synthetic Data Generators for Benchmarking Next-Generation Intrusion Detection Systems,” 2017 IEEE International Conference on Cluster Computing (CLUSTER), pp. 278–289, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Q. Chen, H. A. Kholidy, S. Abdelwahed, and J. Hamilton, “Towards Realizing a Distributed Event and Intrusion Detection System,” Future Network Systems and Security, pp. 70–83, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy and A. Erradi, “A cost-aware model for risk mitigation in Cloud computing systems,” 2015 IEEE/ACS 12th International Conference of Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), pp. 1–7, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy, A. Erradi, and S. Abdelwahed, “Attack Prediction Models for Cloud Intrusion Detection Systems,” 2014 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Modelling and Simulation, pp. 270–275, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy, A. M. Yousof, A. Erradi, S. Abdelwahed, and H. A. Ali, “A Finite Context Intrusion Prediction Model for Cloud Systems with a Probabilistic Suffix Tree,” 2014 European Modelling Symposium, pp. 526–531, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kholidy, A. Erradi, S. Abdelwahed, A. M. Yousof, and H. A. Ali, “Online risk assessment and prediction models for Autonomic Cloud Intrusion srevention systems,” 2014 IEEE/ACS 11th International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), pp. 715–722, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, A. Erradi, S. Abdelwahed, and A. Azab, “A Finite State Hidden Markov Model for Predicting Multistage Attacks in Cloud Systems,” 2014 IEEE 12th International Conference on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, pp. 14–19, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, A. Erradi, S. Abdelwahed, and F. Baiardi, “HA-CIDS: A Hierarchical and Autonomous IDS for Cloud Systems,” 2013 Fifth International Conference on Computational Intelligence, Communication Systems and Networks, pp. 179–184, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, A. Erradi, S. Abdelwahed, and F. Baiardi, “HA-CIDS: A Hierarchical and Autonomous IDS for Cloud Systems,” 2013 Fifth International Conference on Computational Intelligence, Communication Systems and Networks, pp. 179–184, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy and F. Baiardi, “CIDD: A Cloud Intrusion Detection Dataset for Cloud Computing and Masquerade Attacks,” 2012 Ninth International Conference on Information Technology - New Generations, pp. 397–402, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy and F. Baiardi, “CIDS: A Framework for Intrusion Detection in Cloud Systems,” 2012 Ninth International Conference on Information Technology - New Generations, pp. 379–385, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy and N. Chatterjee, “Towards developing an Arabic word alignment annotation tool with some Arabic alignment guidelines,” 2010 10th International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications, pp. 778–783, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hisham A. Kholidy, K. S. Alghathbar, “A New Accelerated RC4 Scheme Using “Ultra Gridsec” and “HIMAN” and use this Scheme to Secure “HIMAN” Data” 2009 Fifth International Conference on Information Assurance and Security, pp. 617–622, 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Azab and Hisham. A. Kholidy, “An adaptive decentralized scheduling mechanism for peer-to-peer Desktop Grids,” 2008 International Conference on Computer Engineering & Systems, pp. 364–371, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Arshad, Patel Tirth, Hisham Kholidy, “Deception Technology: A Method to Reduce the Attack Exposure Time of a SCADA System”. https://dspace.sunyconnect.suny.edu/handle/1951/70148.

- Akshay Bhoite, Diwash Basnet, Hisham Kholidy, “Risk Evaluation for Campus Area Network”. https://dspace.sunyconnect.suny.edu/handle/1951/70162.

- Malkoc, M., & Kholidy, H. A. (2023). 5G Network Slicing: Analysis of Multiple Machine Learning Classifiers. ArXiv. /abs/2310.01747.

- Fathy M. Mustafa, Hisham A. Kholidy, Ahmed F. Sayed et al. Distributed Backward Pumped Raman Amplifier Gain Enhancement: New Approaches, 06 April 2023, available at Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.M., Kholidy, H.A., Sayed, A.F. et al. Backward pumped distributed Raman amplifier: enhanced gain. Opt Quant Electron 55, 772 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Boualem, Adda & Fouchal, Hacène & Ayaida, Marwane & Kholidy, Hisham. (2024). Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases using Nano Sensors Network in Nanofluids. [CrossRef]

- Grippo, T., & Kholidy, H. A. (2022). Detecting Forged Kerberos Tickets in an Active Directory Environment. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, D., & Kholidy, H. A. (2022). An Analysis of Honeypots and their Impact as a Cyber Deception Tactic. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Kholidy, H. A., & Abuzamak, M. (2022). 5G Network Management, Orchestration, and Architecture: A Practical Study of the MonB5G project. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Abuzamak, M., & Kholidy, H. (2022). UAV Based 5G Network: A Practical Survey Study. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Kholidy, H. A., Rahman, M. A., Karam, A., & Akhtar, Z. (2022). Secure Spectrum and Resource Sharing for 5G Networks using a Blockchain-based Decentralized Trusted Computing Platform. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Kholidy, H. A. (2021). State Compression and Quantitative Assessment Model for Assessing Security Risks in the Oil and Gas Transmission Systems. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.14137. [CrossRef]

- Kholidy, H. A. (2021). A Triangular Fuzzy based Multicriteria Decision Making Approach for Assessing Security Risks in 5G Networks. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Haque, N. I., Rahman, M. A., Chen, D., & Kholidy, H. (2021). BIoTA Control-Aware Attack Analytics for Building Internet of Things. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Kholidy, H. A. (2020). Cloud-SCADA Penetrate: Practical Implementation for Hacking Cloud Computing and Critical SCADA Systems. Department of Computer and Network Security, College of Engineering, SUNY Polytechnic Institute.

- S. Hamadache, E. Benkhelifa, Hisham Kholidy, P. Kathiravelu, and B. B. Gupta, “Leveraging SDN for Real World Windfarm Process Automation Architectures,” 2023 Tenth International Conference on Software Defined Systems (SDS), pp. 115–120, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Zouzou, M. Shahawy, E. Benkhelifa, and Hisham Kholidy, “SIoTSim: Simulator for Social Internet of Things,” 2023 10th International Conference on Internet of Things: Systems, Management and Security (IOTSMS), pp. 149–155, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Boualem, C. De Runz, Hisham Kholidy, A. Bengheni, D. Taibi, and M. Ayaida, “A New Classification of Target Coverage Models in WSNs, Survey and Algorithms and Future Directions,” Proceedings of Ninth International Congress on Information and Communication Technology, pp. 249–261, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Andrew Fox, Hisham Kholidy, Ibrahim Almazyad, “Current 5G Federation Trends: A Literature Review”, November 2023. [CrossRef]

- Boualem, A., Fouchal, H., Ayaida, M., Hisham Kholidy. Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases using Nano Sensors Network in Nanofluids. BioNanoSci. 15, 394 (2025). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).