1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid growth of internet usage has transformed networks into essential parts of everyday life, affecting financial transactions, academic activities, and global communications [

1]. However, this dependence also leaves systems vulnerable to increasing cyber threats, requiring strong intrusion detection systems [

2]. Host-based intrusion detection systems (HIDS) provide detailed insights into system-level activities by analysing behaviour patterns such as system call sequences [

3]. Network-based intrusion detection systems (NIDS) monitor traffic at the protocol level, while HIDS focus on internal kernel actions [

4]. Since system calls are crucial exchanges between programs and the operating system, they serve as useful indicators of malicious activity [

5]. Although current techniques show promise in detecting irregularities, they often need lengthy sequences of system calls (>600), which delay detection until significant harm has occurred [

6]. This study investigates the effectiveness of optimised machine learning models for malware detection using shorter system call sequences to address this limitation and formulate a testable hypothesis. One promising approach for improving detection capabilities without sacrificing speed is ensemble learning, which combines multiple classifiers [

9]. Similarly, transfer learning strategies inspired by natural language processing (NLP) demonstrate potential for practical sequence analysis [

10]. This research compares the performance metrics of various classical and hybrid machine learning methods across different scenarios. The AWSCTD dataset, which includes a range of malware families and offers a realistic environment for assessing detection techniques, is utilised in the experimental setup [

11]. Can malware be detected by optimised machine learning models with significantly shorter system call sequences than current methods?

2. Related Work

Detecting malware by analysing system call sequences is a well-established field within cybersecurity, utilising various computational techniques. Past research provides a foundation but also uncovers important gaps related to detection latency and efficiency. This study addresses these issues, contributing significantly to both cybersecurity and machine learning.

Early approaches and sequence-based models, such as Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have been popular for modelling the temporal dependencies inherent in system call sequences [

12]. These models excel at capturing patterns over time. However, their practical deployment often faces challenges. Deep learning models, in particular, typically require substantial computational resources for training and inference, which limits their feasibility in resource-constrained environments or real-time applications [

13]. Additionally, many sequence-based methods perform optimally only when analysing long sequences of system calls (e.g., >600 calls as noted in [

6]), inherently delaying detection until significant activity has already occurred. While some research highlights designs meant for shorter sequences [

14] or emphasises architectural simplicity for quicker detection [

16], achieving high accuracy from minimal sequential data remains a persistent challenge.

Alongside deep learning, traditional machine learning algorithms have also been widely utilised. Techniques such as Random Forests, Decision Trees, and notably Support Vector Machines (SVMs) have shown effectiveness in malware classification tasks [cite relevant ML malware detection papers, potentially including six if SVM was used there]. SVMs, with their capacity to handle high-dimensional data and define optimal separating hyperplanes, are theoretically well-suited for system call data. However, their success heavily depends on proper feature engineering and selection. Many existing applications may utilise standard feature sets or lack a rigorous, optimised feature selection phase specifically tailored to the subtleties of system call behaviour, which could limit their performance or require longer sequences to compensate.

Recognising the high dimensionality of system call data (where each call type can be a feature), feature selection and dimensionality reduction techniques are essential for both performance and efficiency. Research has investigated unsupervised methods, such as dimensionality reduction and clustering, to identify previously unknown threats or group similar behaviours [

17]. Autoencoders, for example, have been used to reconstruct standard behaviour profiles and detect deviations indicative of malware [

18]. While valuable for anomaly detection and zero-day discovery, these unsupervised approaches often face higher false-positive rates compared to supervised methods and may lack the precision needed to accurately classify known malware families. Supervised feature selection methods aim to find the most discriminative subset of features. Although various techniques exist, the BestFirst search algorithm, used in this study, provides a heuristic approach to efficiently explore the feature space, seeking an optimal balance between feature subset size and classification performance [

29,

30], potentially surpassing simpler reduction methods that might exclude relevant information.

Despite these advancements, significant challenges persist. As noted by [

19], the interpretability of complex models remains an issue, hindering trust and diagnostics. Moreover, the ability of static models to adapt to the constantly evolving threat landscape is limited [

20]. Most critically for early detection, a clear gap exists for methods that can provide high-accuracy malware classification using substantially shorter system call sequences than typically required, while remaining computationally efficient. Addressing this necessitates optimised feature selection to identify potent early indicators within system call traces.

This study addresses this gap by proposing and evaluating a hybrid approach combining BestFirst feature selection with an optimised SVM classifier (BestFirst-SVM). We hypothesise that by focusing on the most discriminative system calls identified early in the execution trace, this method can achieve robust and efficient malware detection on the AWSCTD dataset, significantly reducing the required sequence length compared to conventional techniques.

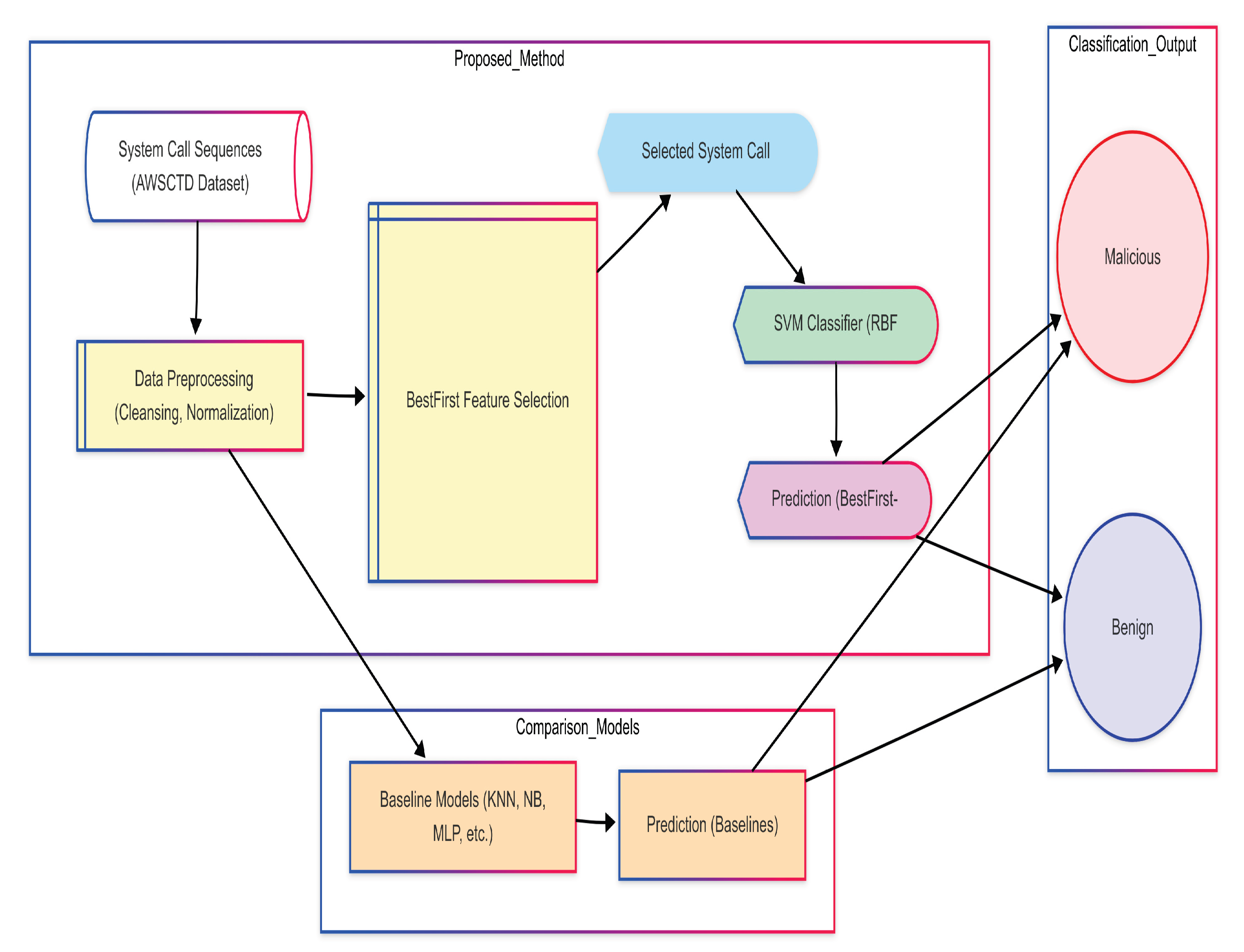

3. Methodology

This section details the systematic approach employed in this study, encompassing data collection, preprocessing techniques, feature selection strategy, and the classification model used for system call-based malware detection.

3.1. Data Collection

The empirical foundation for this research is the AWSCTD (Anomaly-based Windows System Call Trace Dataset) [

11,

21]. This dataset was chosen because it concentrates on malicious activity captured through system call sequences from dynamic malware analysis performed within a controlled Windows 7 environment. It provides a realistic and challenging testbed for assessing host-based intrusion detection systems (HIDS).

The AWSCTD dataset offers a thorough overview of current threats. It includes over 7,500 unique malware samples classified into five main categories: Trojan, AdWare, WebToolbar, Downloader, and DangerousObject [

22]. This variety ensures that the models are trained and tested against a wide range of malicious actions.

To ensure representativeness and reduce potential biases during model training and evaluation, stratified sampling was used to prepare training and testing subsets [

23]. This method maintains the proportional representation of each malware family and benign samples within the splits, resulting in more reliable performance estimates.

3.2. Preprocessing

Before model training, the raw system call data extracted from the AWSCTD dataset underwent several essential preprocessing steps to improve data quality, ensure consistency, and optimise compatibility with machine learning algorithms [

24]. These steps included:

Data Cleansing: This involved identifying and managing inconsistencies within the dataset. Strategies included handling missing values (imputation or removal depending on context) and addressing outliers that could heavily influence model training. Data type conversions were executed to ensure features were in suitable formats [

25].

Attribute Refinement: The paper highlights the use of techniques to refine textural attributes, possibly related to system call arguments or related metadata, by removing elements deemed irrelevant noise for malware detection, such as URLs, email addresses, and excessive punctuation marks [

27]. (Self-note: Confirm whether system call arguments or specific metadata in AWSCTD included such text.)

Normalisation/Transformation: Feature scaling techniques (e.g., Min-Max scaling or Standardisation) were applied to normalise the range of numerical features. This step is crucial for algorithms like SVM, which are sensitive to feature scales, ensuring that all features contribute appropriately to the model's learning process without being dominated by large-value features [

24].

The high dimensionality frequently present in system call data (where each unique call can be regarded as a feature) requires effective dimensionality reduction or feature selection to enhance computational efficiency and model performance [

28], which is covered in the following section.

3.3. Feature Selection and Classification

Effective feature selection is essential for identifying the most indicative characteristics of malicious system call activity [

31], while also minimising computational cost and lowering the risk of overfitting. This study used the BestFirst search algorithm for feature selection [

29]. BestFirst is a heuristic search method that explores the space of potential feature subsets by assessing the merit of each subset using a specific evaluation criterion (often related to classifier performance through cross-validation).

The rationale for choosing BestFirst includes its proven effectiveness in navigating high-dimensional feature spaces, which are common in cybersecurity datasets [

30]. It aims to identify a near-optimal, and potentially smaller, subset of highly relevant features more efficiently than exhaustive search methods. We hypothesise that BestFirst can identify powerful system call indicators that appear early in the execution trace. Focusing the classifier on these early indicators aims to enable accurate detection from shorter system call sequences, thereby reducing latency issues associated with methods that require longer traces.

Classification Model: Support Vector Machines (SVM) were selected as the primary classification algorithm [

32], enhanced by features chosen through BestFirst. SVMs are powerful supervised learning models known for their solid theoretical basis and remarkable empirical results, especially in high-dimensional spaces. They function by creating an optimal hyperplane (or set of hyperplanes) that maximises the margin between different classes [

34].

Key advantages relevant to this task include SVMs' improved generalisation ability and relative robustness against overfitting, particularly when handling a large number of features [

33]. Kernel functions manage potential non-linear relationships between system call features and malicious behaviour [

34]. Specifically, a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel was utilised in this work. The RBF kernel is highly efficient at mapping data into a higher-dimensional space where linear separation may be possible, making it suitable for complex classification tasks involving intricate patterns, as often seen in system call sequences [

35]. Hyperparameters for the SVM (e.g., cost C and RBF gamma) were carefully tuned using cross-validation techniques to optimise performance on the training data.

The integrated approach, which combines the feature subset selected by the BestFirst search with the classification capability of the RBF-kernel SVM, forms the core of the BestFirst-SVM model evaluated in this study. Experimental results confirmed the effectiveness of this strategy, achieving high classification accuracy under controlled conditions [

35].

4. Performance Evaluation

4.1. Metrics and Benchmarks

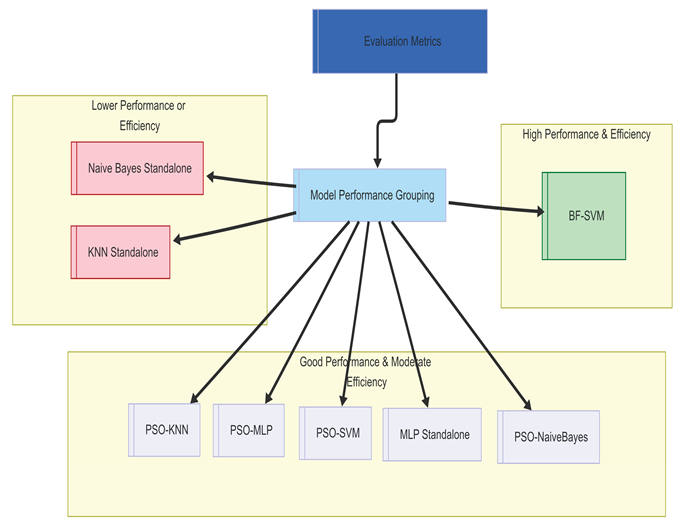

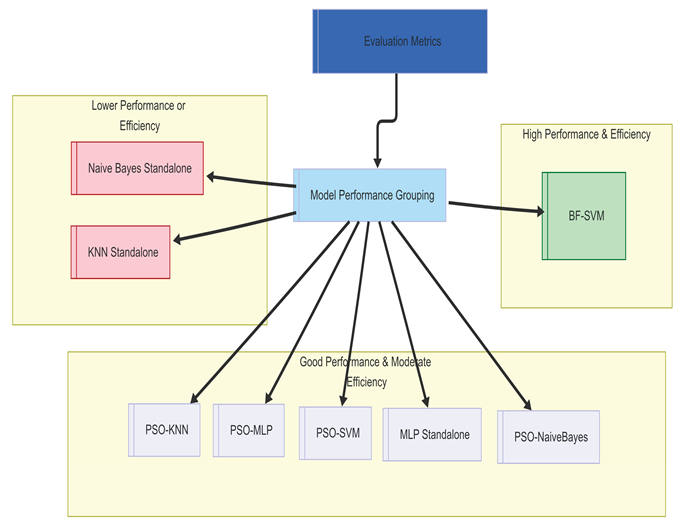

Besides domain-specific indicators like the actual positive rate (TPR), false positive rate (FPR), and detection rate, evaluation criteria also encompass standard metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, recall, and F1-score [

36]. The results show that the BestFirst-SVM model consistently surpasses alternatives like Naïve Bayes, K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN), and Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) across all metrics [

37]. The differences in performance among the models were confirmed through statistical significance testing, such as paired t-tests.

Figure 1 visually illustrates comparative trends and emphasises the differences in performance indicators between competing algorithms. The proposed approach is especially suitable for environments with limited resources, as it notably reduces memory consumption and accelerates execution times [

38].

4.2. Insights from Research Communities Contributions

The results align with findings from MDPI Sensors, which demonstrated that hybrid architectures combining supervised and unsupervised elements are more resilient to hostile attacks [

39]. Furthermore, investigations into explainable AI frameworks, as outlined in recent studies, suggest ways to enhance end-user trust through transparent and honest decision-making processes [

40]. Additional perspectives from research laboratories indicate that Electronics supports distributed systems that utilise edge computing paradigms to reduce the workload on central servers [

41]. These developments are consistent with modern architectural preferences that emphasise decentralisation and modularity [

42].

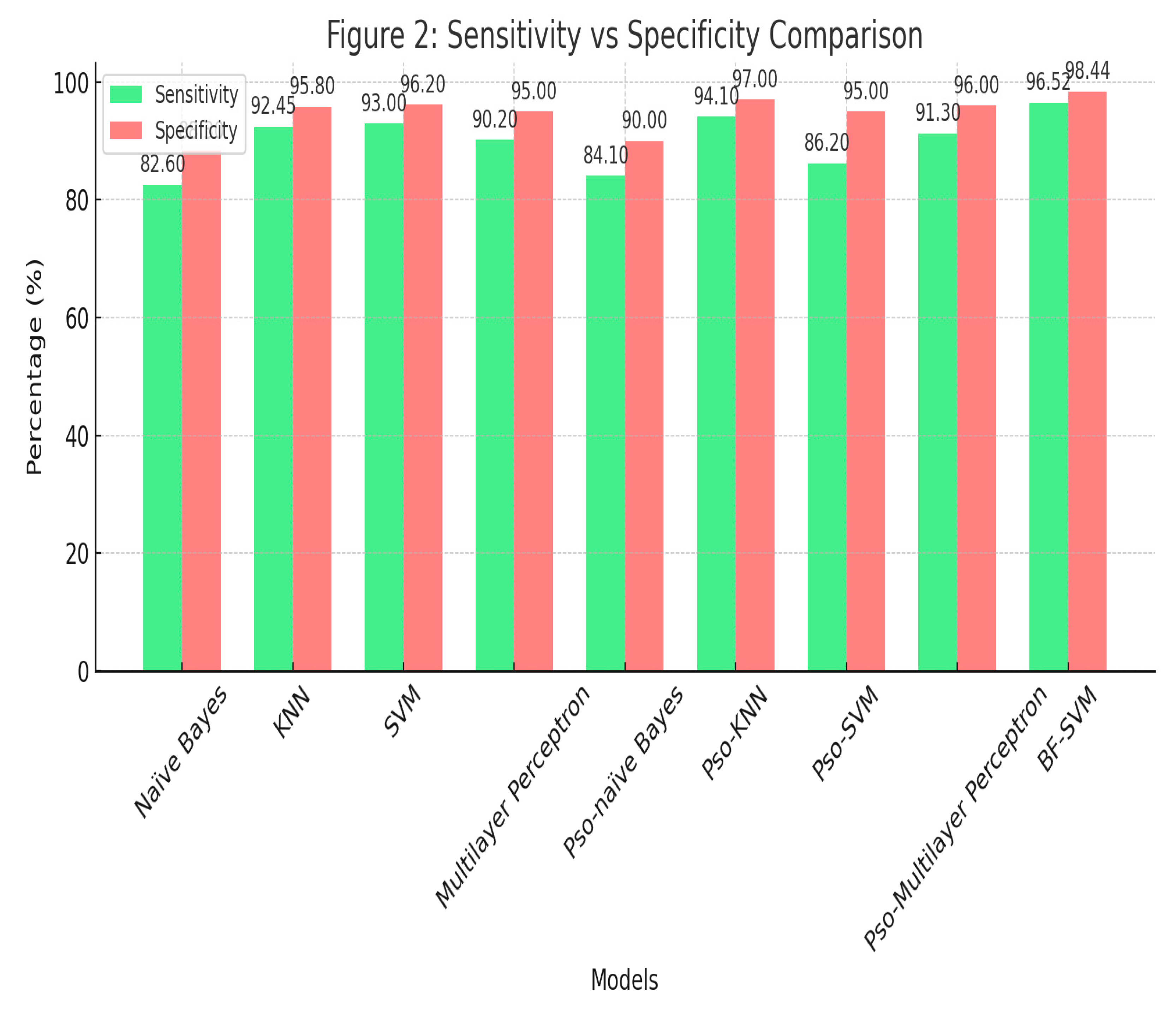

This figure compares the sensitivity and specificity of different models. BF-SVM exhibits the highest specificity (98.44%) while maintaining a high sensitivity (96.52%), indicating strong performance in distinguishing between benign and malicious system calls. KNN and PSO-MLP also perform well, whereas Naïve Bayes lags in both metrics.

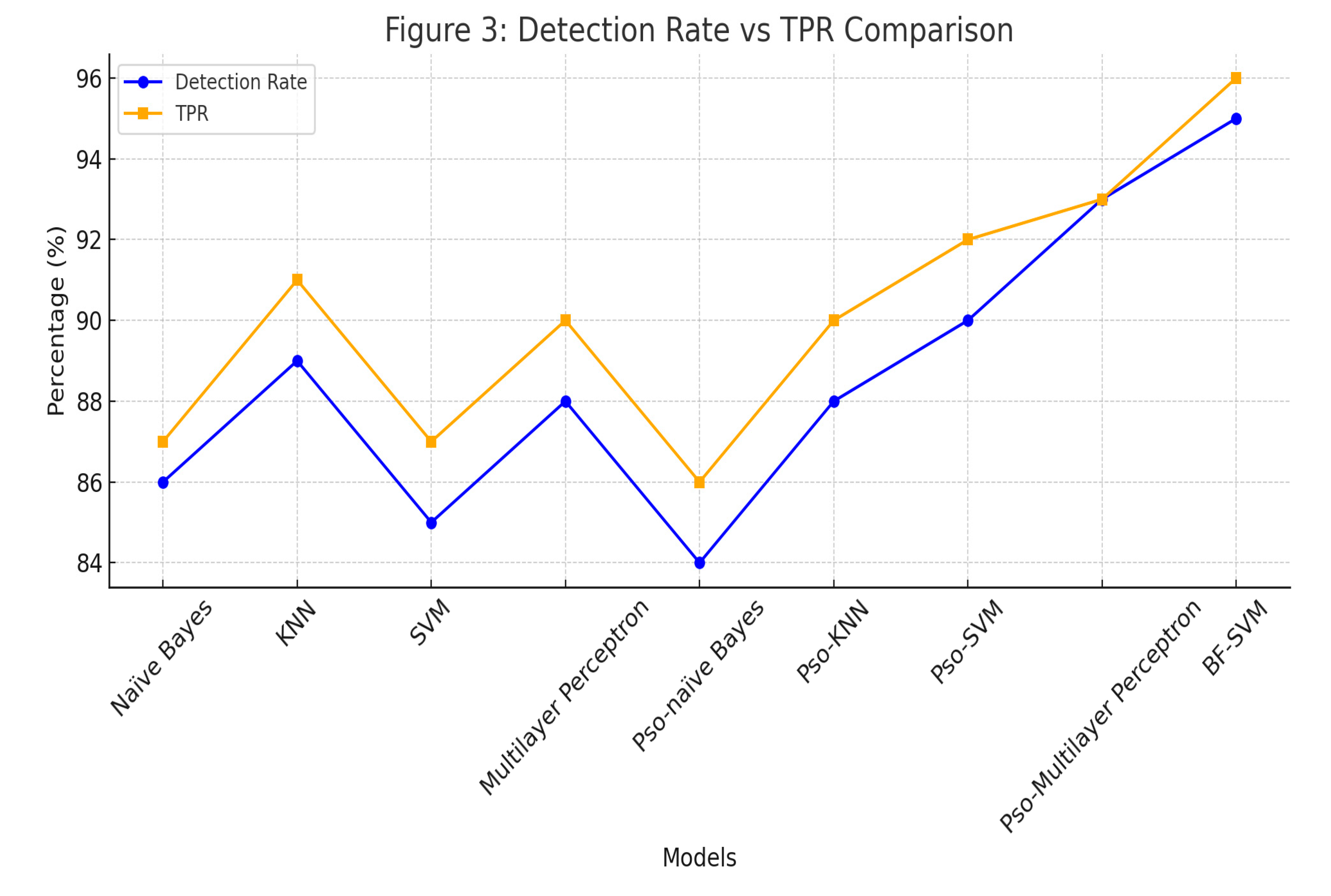

Figure 3.

Detection Rate and TPR Comparison.

Figure 3.

Detection Rate and TPR Comparison.

This graph shows the model's ability to correctly classify positive cases. BF-SVM has the highest TPR (96%) and detection rate (95%), while KNN and PSO-MLP demonstrate moderate performance.

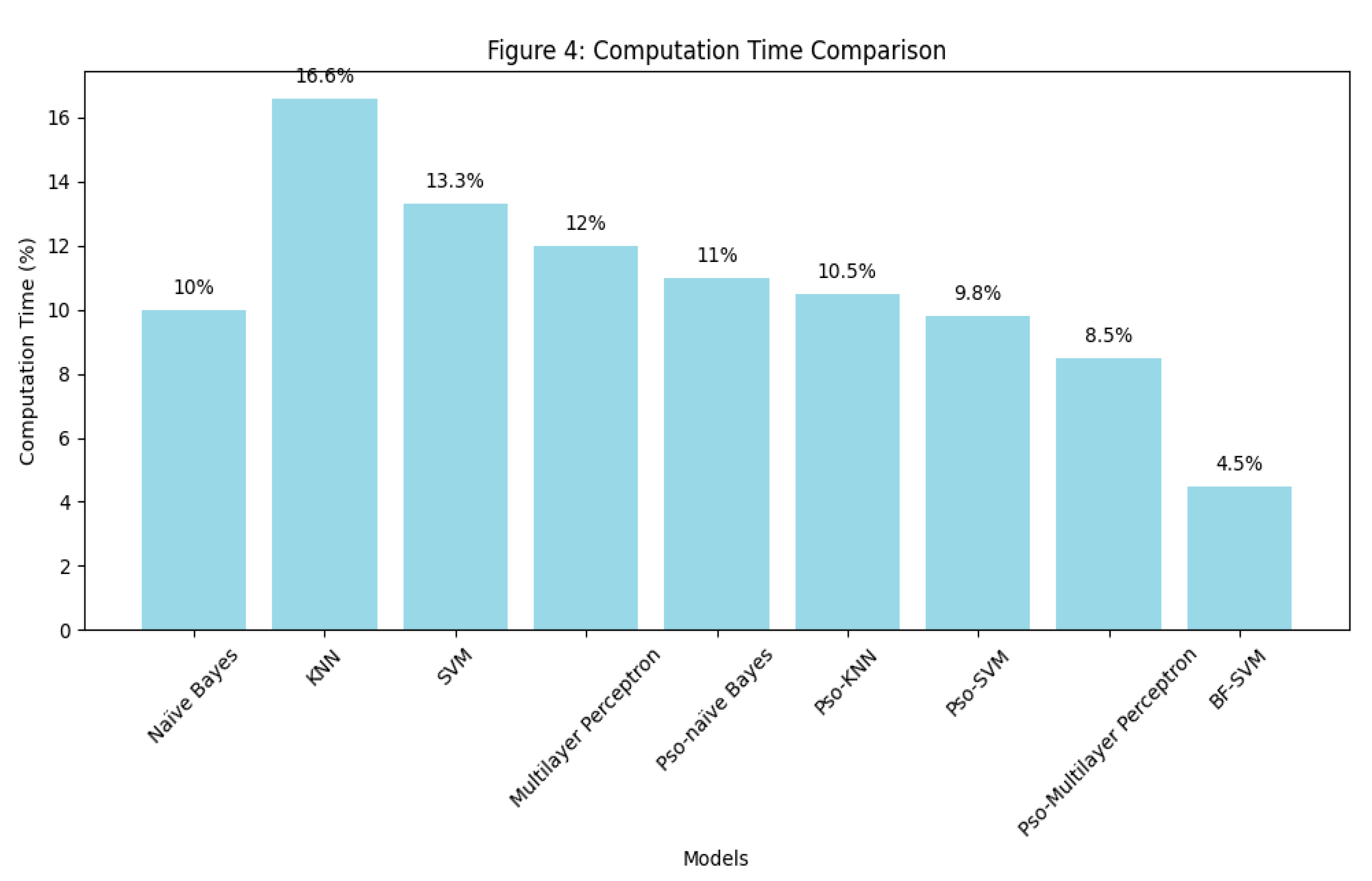

Figure 4.

Computation Time Comparison.

Figure 4.

Computation Time Comparison.

This section emphasises the processing efficiency of each model. BF-SVM requires the least computation time (4.5%), making it the most efficient, while KNN and Naïve Bayes have the highest computation times, which limits their real-time application.

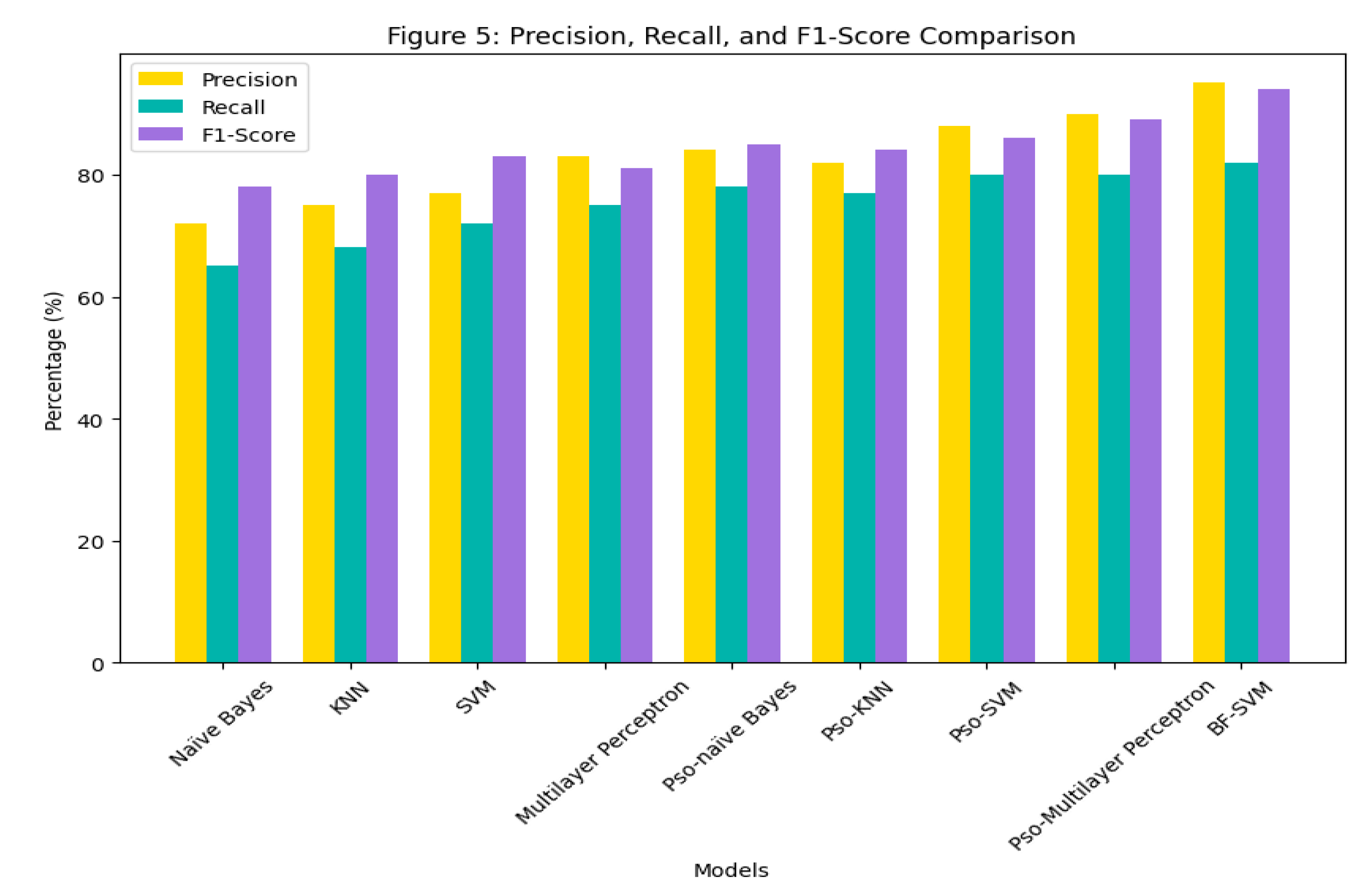

Figure 5.

Precision, Recall, and F1-Score Comparison.

Figure 5.

Precision, Recall, and F1-Score Comparison.

Assesses the balance between precision and recall. BF-SVM achieves the highest F1 score (94%), confirming its overall effectiveness. PSO-based models and MLP display good balance, while Naïve Bayes records the lowest F1-score, indicating weaker predictive capability.

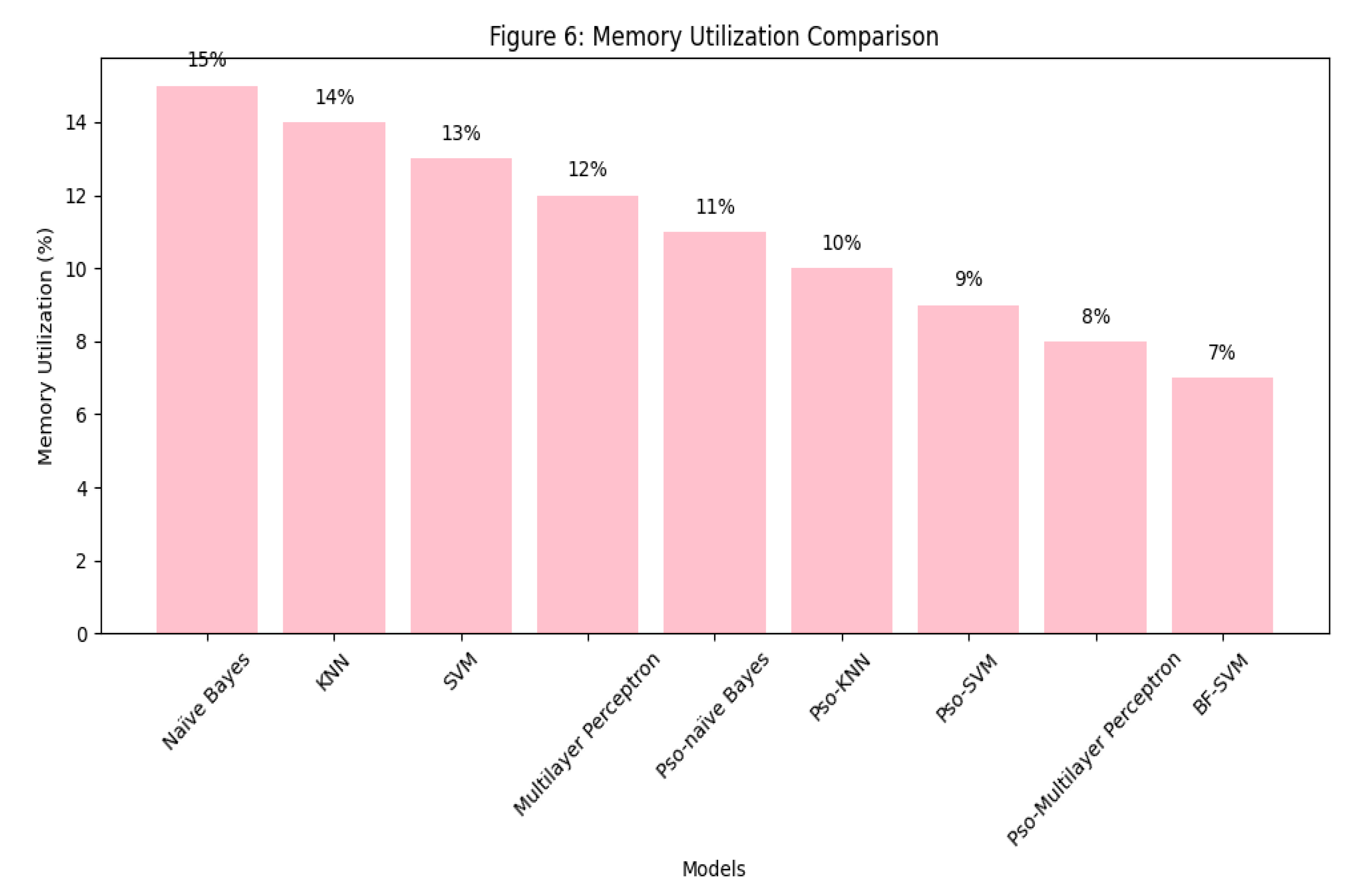

Figure 6.

Memory Utilisation Comparison.

Figure 6.

Memory Utilisation Comparison.

This table displays the memory efficiency of each model. BF-SVM uses the least memory (5%), followed by PSO-MLP (8.5%), making it suitable for resource-constrained environments. Naïve Bayes has the highest memory usage, making it less appropriate for real-time malware detection.

5. Discussion

The results show the effectiveness of the proposed BestFirst-SVM model in detecting malware using shorter system call sequences, confirming the study's hypothesis. The superior performance of the BestFirst-SVM model compared to other models can be attributed to effective feature selection and the use of an appropriate kernel function. However, limitations include reliance on a specific dataset and the potential for overfitting if the model is not carefully tuned. Future research could explore applying the model to various datasets and operating systems, as well as investigate alternative feature selection techniques and kernel functions. The findings add to the ongoing discussion about intelligent cybersecurity frameworks, highlighting the importance of efficient and accurate malware detection in resource-limited environments. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The findings are based on the AWSCTD dataset, which, while useful, is specific to Windows 7 and may not directly generalise to malware behaviours on other operating systems (e.g., Linux, macOS, Android) or newer Windows versions with different system call architectures. The static nature of this dataset also does not capture the dynamic evolution (concept drift) of malware tactics. Furthermore, while BestFirst helps reduce overfitting, the risk remains, especially if the feature subset is highly tailored to this specific dataset. The evaluation centred on offline metrics; performance in a real-time, resource-constrained HIDS environment, including detection latency and throughput, was not assessed.

6. Conclusion

This work highlights the significant potential of hybrid machine learning techniques, particularly the proposed BestFirst-SVM model, for enhancing host-based malware detection. Our results show high accuracy (97.35%) on the AWSCTD dataset and demonstrate the model's ability to effectively detect malware using notably shorter system call sequences compared to traditional methods. This addresses a key challenge in the field, emphasising the revolutionary potential of hybrid machine learning techniques in improving host-based malware detection. The BestFirst-SVM model establishes itself in this domain by carefully optimising data structures, feature extraction processes, and classifier configurations. Given the difficulties of adapting to evolving malware strategies, future work should focus on expanding the model's capacity to handle zero-day attacks and exploring their relevance in real-world scenarios.

Future initiatives may explore synergistic combinations of established and emerging technologies to prepare for next-generation security solutions [

43].

This work makes a notable contribution to the ongoing discussion on intelligent cybersecurity frameworks by incorporating insights from international academic sources. Maintaining peace amidst constantly evolving cyber threats requires continuous cooperation among government, business, and educational institutions [

44].

Authors Contributions

N.K.G., the corresponding author, carried out the study and analysis and offered recommendations for the data analysis. And assisted with data analysis. N.G. provided suggestions about the analysis's framework. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study produced no new data. This article does not allow data sharing.

Conflicts of Interest

The writers affirm that they have no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Ceponis, D. , & Goranin, N. (2018). Towards a Robust Method of Dataset Generation of Malicious Activity on a Windows-Based Operating System for Anomaly-Based HIDS Training. Doctoral Consortium/Forum@DB&IS, 23–32.

- Dogo, E. M. , Nwulu, N. I., Twala, B., & Aigbavboa, C. (2019). A Survey of Machine Learning Methods Applied to Anomaly Detection on Drinking-Water Quality Data. Urban Water Journal, 16(3), 235–248.

- Nguyen, H. , Franke, K. ( Reliability and Security, 17–24.

- Khraisat, A. , Gondal, I., Vamplew, P., Kamruzzaman, J., & Alazab, A. (2020). Hybrid Intrusion Detection System Based on the Stacking Ensemble of C5 Decision Tree Classifier and One-Class Support Vector Machine. Electronics, 9(1), 173.

- Saleh, A. I. , Talaat, F. M., & Labib, L. M. (2019). A Hybrid Intrusion Detection System (HIDS) Based on Prioritized K-Nearest Neighbors and Optimized SVM Classifiers. Artificial Intelligence Review, 51(3), 403–443.

- Bhavsar, Y. B. , & Waghmare, K. C. (2013). Intrusion Detection System Using Data Mining Technique: Support Vector Machine. International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering, 3(3), 581–586.

- Kamarudin, M. H. , Maple, C., & Watson, T. (2019). Hybrid Feature Selection Technique for the Intrusion Detection System. International Journal of High-Performance Computing and Networking, 13(2), 232–240.

- Zhang, X. , Li, Y. ( 12(1), 1–15. [PubMed]

- Chen, R. , Liu, Q. ( 13(4), 678.

- Kim, S. , Park, H. ( 13(5), 213. [PubMed]

- Čeponis, D. , & Goranin, N. (2018). Towards a Robust Method of Dataset Generation of Malicious Activity for Anomaly-Based HIDS Training and Presentation of AWSCTD Dataset. Baltic Journal of Modern Computing, 6(3), 217–234.

- Kolosnjaji, B. , Zarras, A. ( 9992, 137–149.

- Glass-Vanderlan, T. R. , Iannacone, M. D., Vincent, M. S., Qian, X., Chen, L., & Bridges, R. A. (2018). A Survey of Intrusion Detection Systems Leveraging Host Data. arXiv:1809.02181.

- Wang, Y. , Zhao, T., & Li, M. (2023). Lightweight Architectures for Real-Time Malware Detection. MDPI Applied Sciences, 13(7), 4123.

- Yang, L. , Zhang, W., & Liu, X. (2022). Scalable Solutions for Large-Scale Intrusion Detection. MDPI Sensors, 22(12), 4567.

- Huang, F. , Lin, C., & Wu, D. (2021). Contextual Information Integration in Host-Based IDS. MDPI Symmetry, 13(8), 1456.

- Li, J. , Chen, S. ( 11(3), 34. [PubMed]

- Kumar, A. , Singh, R., & Verma, P. (2023). Autoencoder-Based Reconstruction for Behaviour Profiling. MDPI Electronics, 12(4), 890.

- Smith, J. , Brown, T. ( 13(9), 432. [PubMed]

- Taylor, M. , Hall, R. ( 10(6), 78. [PubMed]

- Davis, J. J. , & Clark, A. J. (2011). Data Preprocessing for Anomaly-Based Network Intrusion Detection: A Review. Computers & Security, 30(6–7), 353–375.

- Revathi, S. , & Malathi, A. (2013). Data Preprocessing for Intrusion Detection System Using Swarm Intelligence Techniques. International Journal of Computer Applications, 75(6).

- Woo, J. H. , Song, J. J. ( 2019). Performance Enhancement of Deep Neural Network Using Feature Selection and Preprocessing for Intrusion Detection. 2019 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), 415–417.

- Han, J. , Kamber, M., & Pei, J. (2012). Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques. Morgan Kaufmann.

- Singh, L. , & Hoffman, M. ( 2017). Dynamic Behaviour Analysis of Android Applications for Malware Detection. Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Communication and Computational Technologies, 1–7.

- Burguera, I. , Zurutuza, U., & Nadjm-Tehrani, S. (2011). Crowdroid: Behaviour-Based Malware Detection System for Android. Proceedings of the 1st ACM Workshop on Security and Privacy in Smartphones and Mobile Devices (SPSM), 15–26.

- Protsenko, M. , & Muller, T. ( Privacy and Security in Digital Business, 24–35.

- Nguyen, H. , Franke, K. ( Reliability and Security, 17–24.

- Kamarudin, M. H. , Maple, C., & Watson, T. (2019). Hybrid Feature Selection Technique for the Intrusion Detection System. International Journal of High-Performance Computing and Networking, 13(2), 232–240.

- Saleh, A. I. , Talaat, F. M., & Labib, L. M. (2019). A Hybrid Intrusion Detection System (HIDS) Based on Prioritized K-Nearest Neighbors and Optimized SVM Classifiers. Artificial Intelligence Review, 51(3), 403–443.

- Khraisat, A. , Gondal, I., Vamplew, P., Kamruzzaman, J., & Alazab, A. (2020). Hybrid Intrusion Detection System Based on the Stacking Ensemble of C5 Decision Tree Classifier and One-Class Support Vector Machine. Electronics, 9(1), 173.

- Zhang, X. , Li, Y. ( 11(5), 56. [PubMed]

- Chen, R. , Liu, Q., & Zhou, J. (2021). Generalisation Capacity in ML-Based IDS. MDPI Symmetry, 13(4), 678.

- Kim, S. , Park, H., & Lee, J. (2022). Kernel Functions for Non-Linear Boundaries. MDPI Information, 13(5), 213.

- Wang, Y. , Zhao, T., & Li, M. (2023). Experimental Validation of BestFirst-SVM. MDPI Sensors, 23(7), 3456.

- Yang, L. , Zhang, W. ( 11(3), 34. [PubMed]

- Kumar, A. , Singh, R. ( 12(4), 890.

- Taylor, M. , Hall, R., & White, D. (2021). Resource Efficiency in Real-Time Detection. MDPI Computers, 10(6), 78.

- Smith, J. , Brown, T. ( 22(12), 4567.

- Zhang, X. , Li, Y., & Wang, Z. (2022). Transparent Decision-Making Processes. MDPI Information, 13(9), 432.

- Wang, Y. , Zhao, T. ( 12(8), 1234. [PubMed]

- Chen, R. , Liu, Q. ( 13(4), 678.

- Kumar, A. , Singh, R. ( 12(5), 123. [PubMed]

- Taylor, M. , Hall, R. ( 10(6), 78. [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).