Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

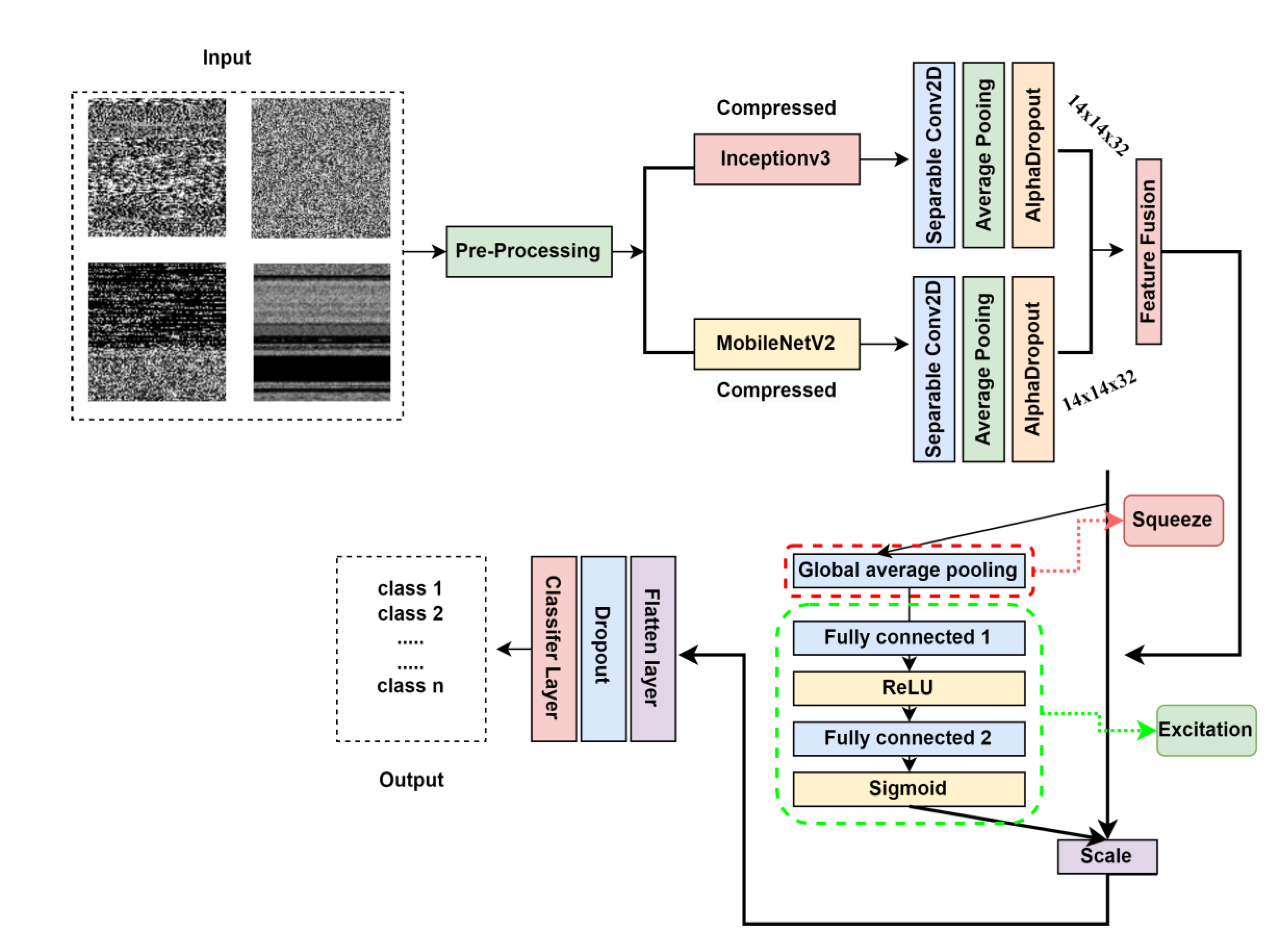

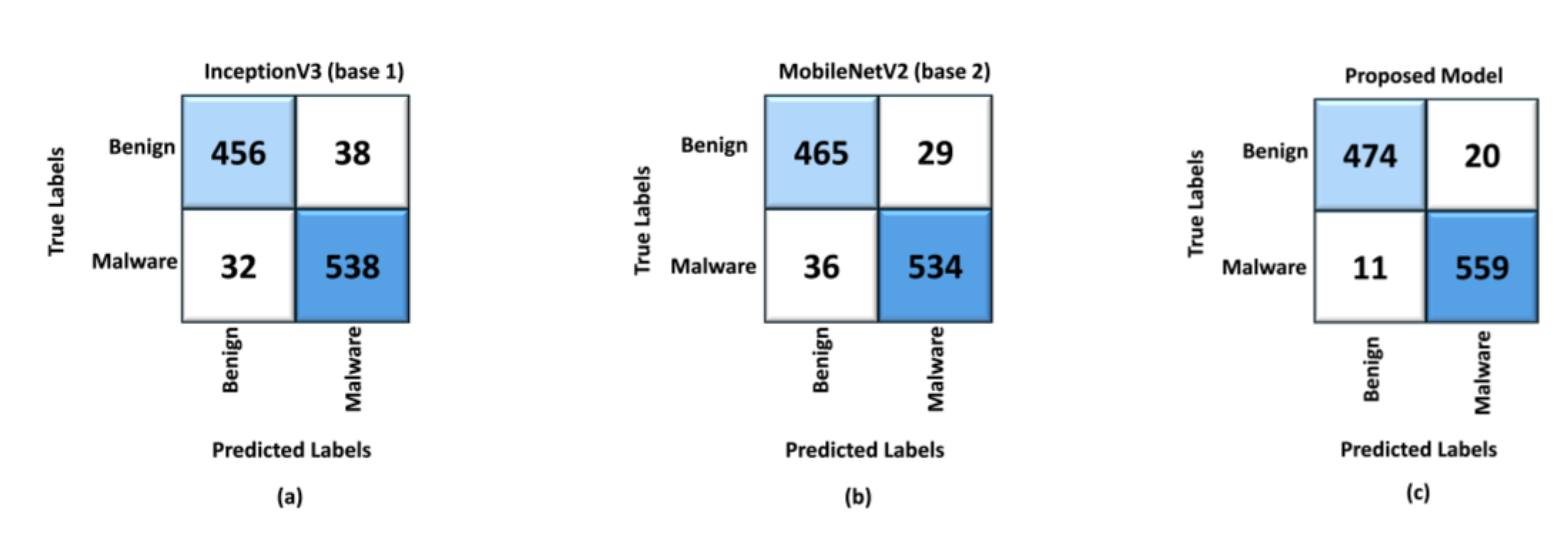

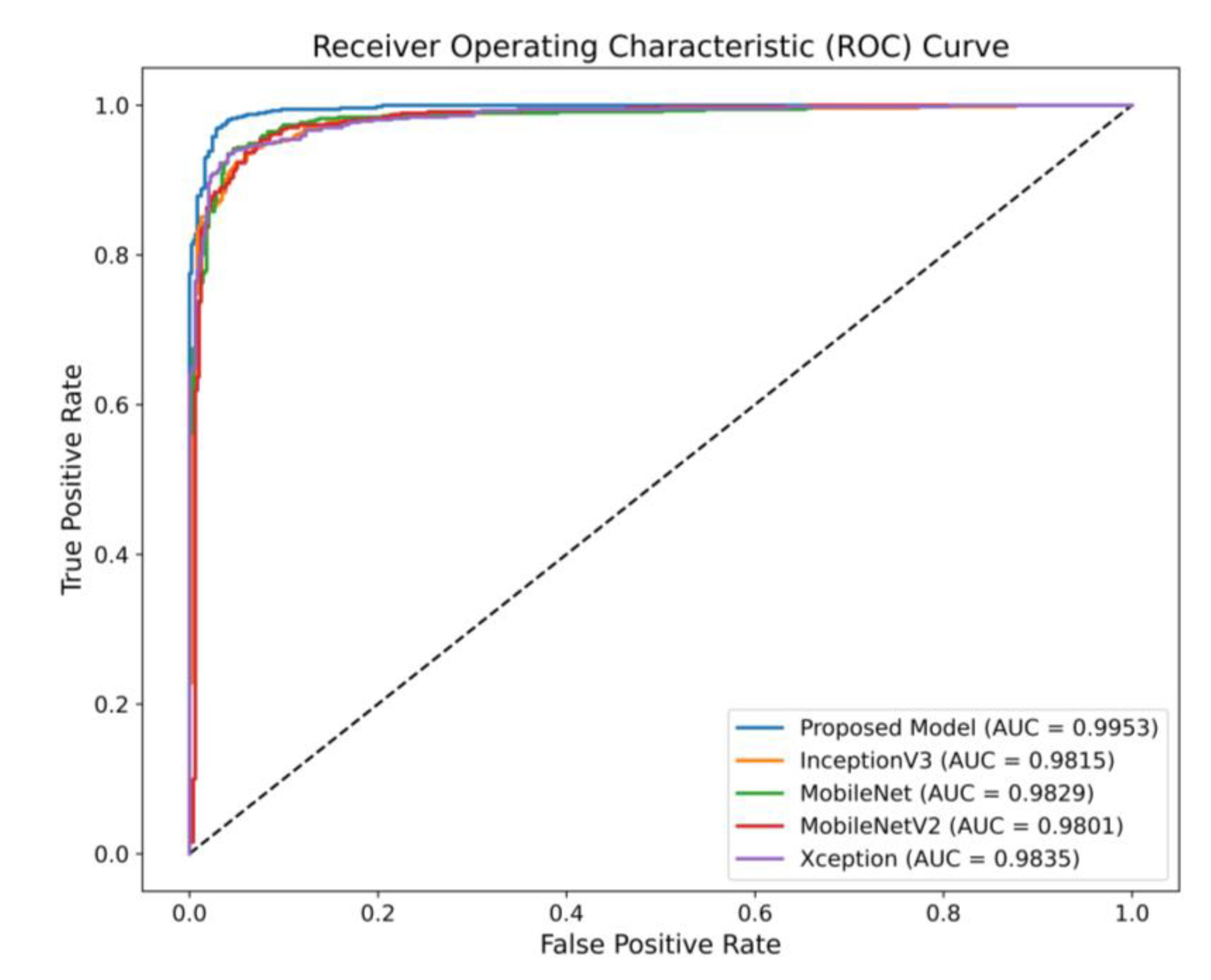

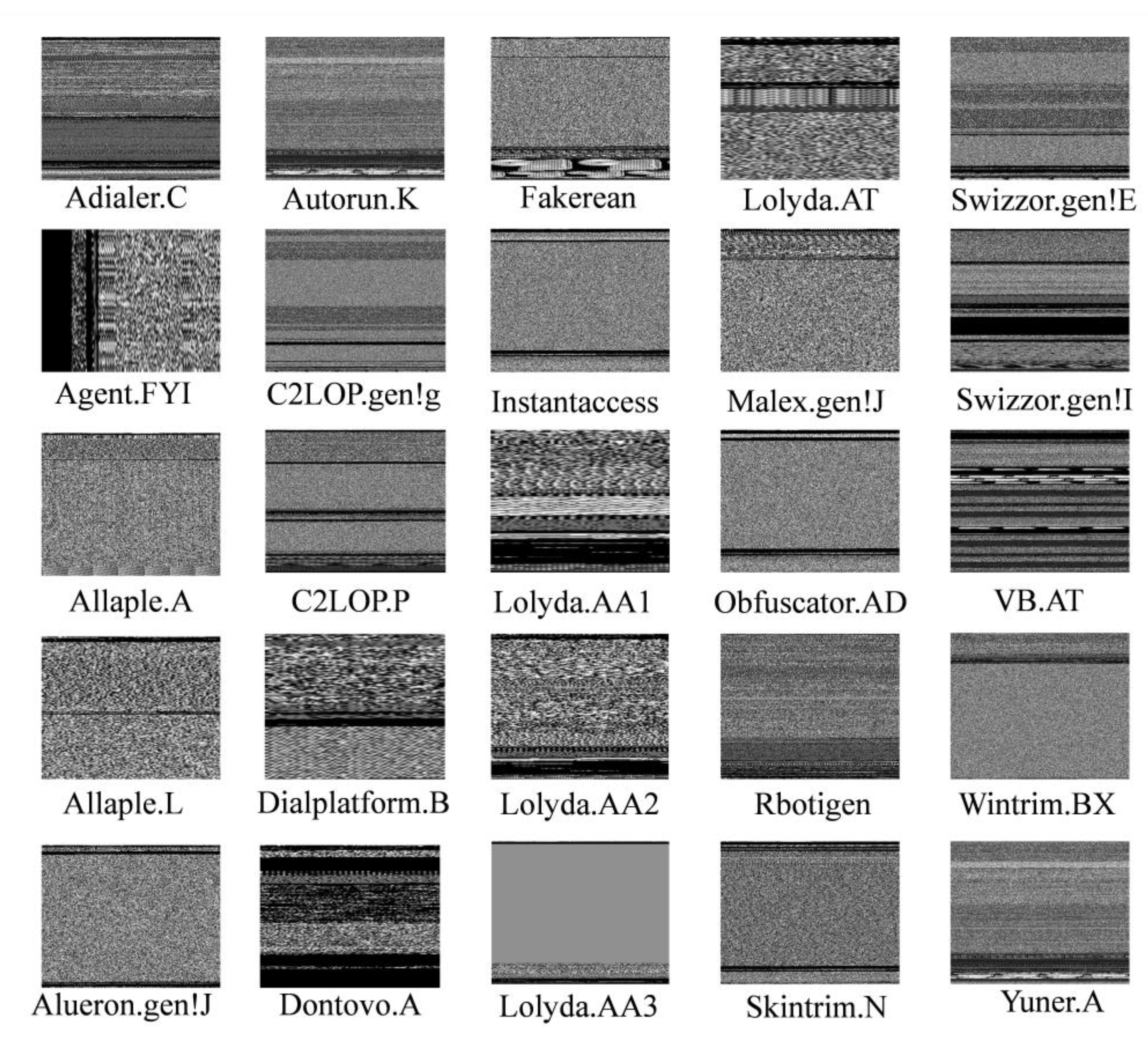

The detection of malware attacks remains a significant challenge due rapid increase in variety of malicious files. An efficient system is crucial to ensure robust malware protection and to support post-attack recovery systems. In response to this challenge, we propose a novel deep learning-based framework which is designed to improve the accuracy and effectiveness of malware attacks detection. The framework employes two advanced pre-trained models including InceptionV3 and MobileNetV2, which are known for their robust feature extraction capabilities. To make the models computationally more efficient, we implement a truncation and compression process to eliminate redundant information, thereby refining the feature extraction workflow. Following this, we perform feature fusion process by combining the strengths of both models to create a more robust feature set. To further refine the combined features, we integrate a Squeeze and Excitation attention block, which enhances the model's ability to focus on the most relevant features for classification. This work addresses the complexities of malware classification in an evolving threat landscape. By effectively leveraging pre-trained models and enhancing them with feature fusion and attention mechanisms, our framework proves to be a robust tool for both binary and multi-class malware classification, making a significant contribution to cybersecurity. Our proposed framework was tested on two datasets. The first is an IoT malware dataset designed for binary classification, where the model achieved an accuracy of 97.09%. The second is the MALIMG dataset, which includes 25 distinct malware classes. On this dataset, the model achieved an accuracy of 97.47%. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach in accurately classifying malware across different types and classes. We assessed the robustness of our model through a comprehensive analysis, including confusion matrix evaluations, ROC curve assessments, and class-wise performance analysis. These methods demonstrated the model's accuracy and reliability across different malware classes, further validating its effectiveness in real-world scenarios.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Motivation and Major contribution

- We introduce a novel and more efficient framework to enhance the accuracy and computational efficiency of malware attack detection. This framework leverages advanced feature fusion approach to effectively classify different types of malwares.

- Our approach involves the utilization and optimization of two advanced pre-trained models named InceptionV3 and MobileNetV2. By truncating and compressing these models, we eliminate redundant information, thereby enhancing the feature extraction process. This refinement significantly reduces computational overhead while maintaining high accuracy.

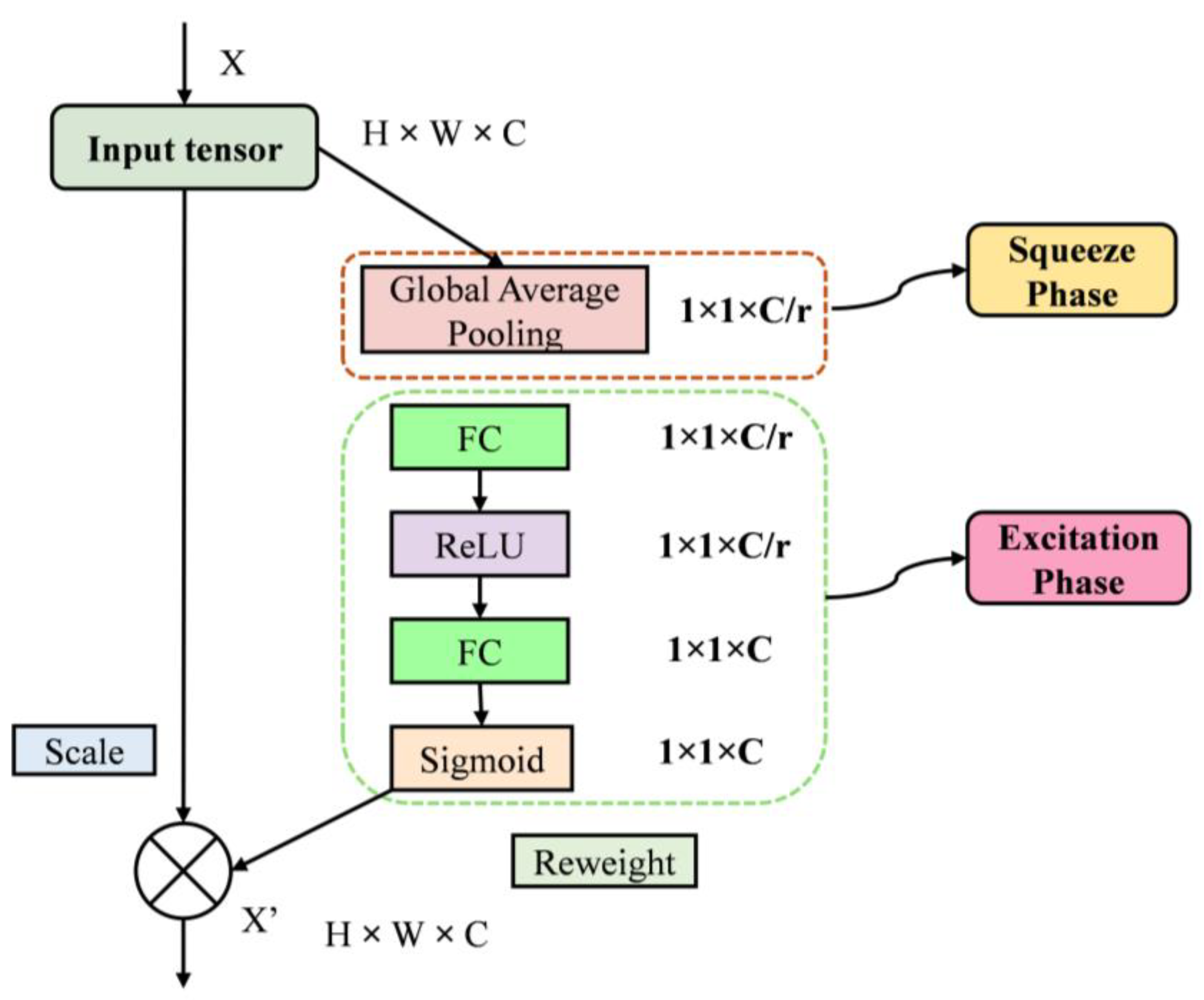

- We combine the feature extraction capabilities of both InceptionV3 and MobileNetV2 through a feature fusion process, creating a robust and comprehensive set of features. Additionally, the incorporation of a Squeeze and Excitation attention block allows the model to focus on the most critical features, thereby improving the precision of malware classification.

- The effectiveness of proposed method is validated using extensive experiments on two diverse datasets: an IoT malware dataset and the MALIMG dataset. Our model achieves a remarkable accuracy of 97.09% on the IoT malware dataset and 97.47% on the MALIMG dataset, demonstrating its robustness in both binary and multi-class malware classification tasks.

- These contributions not only advance the field of malware detection but also offer a practical solution for real-world cybersecurity applications, providing enhanced protection against a wide range of malware threats.

3. Related work

4. Proposed Methodology

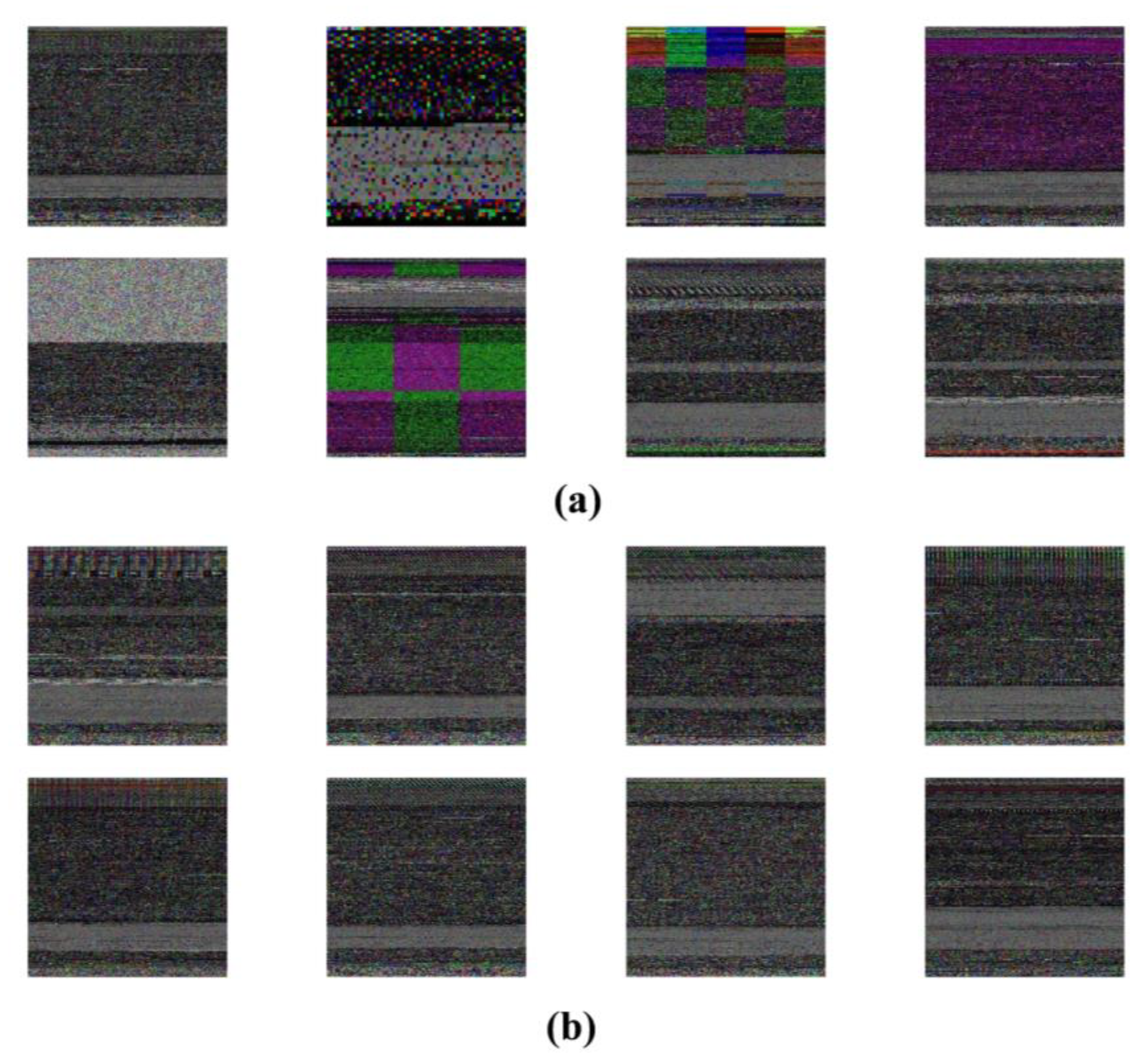

4.1. Dataset Description

4.2. Pre-trained models for feature extraction

4.3. Models’ truncation and compression

4.4. Squeeze and Excitation Block

4.5. Proposed Feature Fusion Architecture

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

5.1. Implementation Details

5.2. Hyperparameters details

5.3. Performance Evaluation

5.4. Performance Analysis

5.5. Ablation study

5.6. Additional experiments on Malimg dataset

5.7. Performance Analysis on Malimg dataset

5.8. Limitations and future work

5.8.1. Limitations

5.8.2. Future work

6. Conclusion

References

- Yuanming, L. and R. Latih, A Comprehensive Review of Machine Learning Approaches for Detecting Malicious Software. International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering & Information Technology, 2024. 14(3).

- GOUIZA, N., H. JEBARI, and K. REKLAOUI, INTEGRATION OF IOT-ENABLED TECHNOLOGIES AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN DIVERSE DOMAINS: RECENT ADVANCEMENTS AND FUTURE TRENDS. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 2024. 102(5).

- Kannari, P.R., N. S. Chowdary, and R.L. Biradar, An anomaly-based intrusion detection system using recursive feature elimination technique for improved attack detection. Theoretical Computer Science, 2022. 931: p. 56-64.

- Seymour, W. , Examining Trends and Experiences of the Last Four Years of Socially Engineered Ransomware Attacks. 2022.

- Bolat, P. and G. Kayişoğlu, Cyber Security. Security Studies: Classic to Post-Modern Approaches, 2023: p. 173.

- Asam, M. , et al., IoT malware detection architecture using a novel channel boosted and squeezed CNN. Scientific Reports, 2022. 12(1): p. 15498.

- Odii, J. , et al., COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF MALWARE DETECTION TECHNIQUES USING SIGNATURE, BEHAVIOUR AND HEURISTICS. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Security (IJCSIS), 2019. 17(7).

- Yunmar, R.A., S. S. Kusumawardani, and F. Mohsen, Hybrid Android Malware Detection: A Review of Heuristic-Based Approach. IEEE Access, 2024. 12: p. 41255-41286.

- Khraisat, A. , et al., Survey of intrusion detection systems: techniques, datasets and challenges. Cybersecurity, 2019. 2(1): p. 1-22.

- Saheed, Y.K. , et al., A machine learning-based intrusion detection for detecting internet of things network attacks. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2022. 61(12): p. 9395-9409.

- Vishwakarma, M. and N. Kesswani, DIDS: A Deep Neural Network based real-time Intrusion detection system for IoT. Decision Analytics Journal, 2022. 5: p. 100142.

- Narayanan, B.N., O. Djaneye-Boundjou, and T.M. Kebede. Performance analysis of machine learning and pattern recognition algorithms for malware classification. in 2016 IEEE national aerospace and electronics conference (NAECON) and ohio innovation summit (OIS). 2016. IEEE.

- Zhang, H. , et al., Classification of ransomware families with machine learning based onN-gram of opcodes. Future Generation Computer Systems, 2019. 90: p. 211-221.

- Ijaz, A. , et al., Innovative Machine Learning Techniques for Malware Detection. Journal of Computing & Biomedical Informatics, 2024. 7(01): p. 403-424.

- Schultz, M.G. , et al. Data mining methods for detection of new malicious executables. in Proceedings 2001 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. S&P 2001. 2000. IEEE.

- Deng, H. , et al., MCTVD: A malware classification method based on three-channel visualization and deep learning. Computers & Security, 2023. 126: p. 103084.

- D’Angelo, G., M. Ficco, and F. Palmieri, Association rule-based malware classification using common subsequences of API calls. Applied Soft Computing, 2021. 105: p. 107234.

- Jain, M., W. Andreopoulos, and M. Stamp, Convolutional neural networks and extreme learning machines for malware classification. Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques, 2020. 16: p. 229-244.

- Kasongo, S.M. and Y. Sun, A deep learning method with wrapper based feature extraction for wireless intrusion detection system. Computers & Security, 2020. 92: p. 101752.

- Naeem, H., B. Guo, and M.R. Naeem. A light-weight malware static visual analysis for IoT infrastructure. in 2018 International conference on artificial intelligence and big data (ICAIBD). 2018. IEEE.

- Vasan, D. , et al., IMCFN: Image-based malware classification using fine-tuned convolutional neural network architecture. Computer Networks, 2020. 171: p. 107138.

- Vasan, D. , et al., Image-Based malware classification using ensemble of CNN architectures (IMCEC). Computers & Security, 2020. 92: p. 101748.

- Kumar, S., B. Janet, and S. Neelakantan, IMCNN: Intelligent Malware Classification using Deep Convolution Neural Networks as Transfer learning and ensemble learning in honeypot enabled organizational network. Computer Communications, 2024. 216: p. 16-33.

- Szegedy, C. , et al. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016.

- Sandler, M. , et al. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J., L. Shen, and G. Sun. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nataraj, L. , et al. Malware images: visualization and automatic classification. in Proceedings of the 8th international symposium on visualization for cyber security. 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Classes | Train images | Test images | Total images |

|---|---|---|---|

| benign | 1989 | 494 | 2,483 |

| malware | 2290 | 570 | 2860 |

| Models | Classes | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| InceptionV3 (Base 1) | Benign | 93.44 | 92.31 | 92.87 | 93.42 |

| Malware | 93.40 | 94.39 | 93.89 | ||

| MobileNetV2 (Base 2) | Benign | 92.81 | 94.13 | 93.47 | 93.89 |

| Malware | 94.85 | 93.68 | 94.26 | ||

| Proposed Model | Benign | 97.73 | 95.95 | 96.83 | 97.09 |

| Malware | 96.55 | 98.07 | 97.30 |

| Models | Classes | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-score (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed Model w/o attention block | Benign | 97.92 | 95.14 | 96.51 | 96.80 |

| Malware | 95.89 | 98.25 | 97.05 | ||

| Proposed Model with attention block | Benign | 97.73 | 95.95 | 96.83 | 97.09 |

| Malware | 96.55 | 98.07 | 97.30 |

| Model | Classes | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adialer.C | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Agent.FYI | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Allaple.A | 0.9921 | 1.0000 | 0.9960 | ||

| Allaple.L | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Alueron.gen!J | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Autorun.K | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| C2LOP.gen!g | 0.8621 | 1.0000 | 0.9259 | ||

| C2LOP.P | 0.9565 | 0.8800 | 0.9167 | ||

| Dialplatform.B | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Dontovo.A | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Fakerean | 1.0000 | 0.9867 | 0.9933 | ||

| Proposed Model | Instantaccess | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9747 |

| Lolyda.AA1 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Lolyda.AA2 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Lolyda.AA3 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Lolyda.AT | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Malex.gen!J | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Obfuscator.AD | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Rbotigen | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Skintrim.N | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Swizzor.gen!E | 0.6538 | 0.6800 | 0.6667 | ||

| Swizzor.gen!I | 0.6667 | 0.5600 | 0.6087 | ||

| VB.AT | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| Wintrim.BX | 0.9615 | 1.0000 | 0.9804 | ||

| Yuner.A | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).