1. Introduction

Cybersecurity threats are evolving rapidly in both complexity and scope, driven by the accelerating pace of technological advancement. These threats impact individuals, organizations, and nations alike. Among them, malware, malicious software designed to compromise devices, remains one of the most persistent and damaging [

1]. In response to traditional detection methods, attackers are increasingly adopting tactics such as data obfuscation, which obscure identifying characteristics and make malicious code harder to detect and classify [

2].

Machine learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has emerged as a powerful tool in modern cybersecurity due to its capacity to automatically learn complex and abstract features from large volumes of malware image data [

3]. However, despite notable progress in CNN-based malware detection, these models often experience significant performance degradation when evaluated against obfuscated samples [

3]. This limitation highlights the need to enhance the robustness and adaptability of detection systems. An effective model must accurately identify malware families, even when obfuscation introduces conflicting or misleading visual patterns.

This study addresses that challenge by applying advanced CNN architectures, including MobileNet, ResNet, and DenseNet, augmented with robust hashing techniques and obfuscation-aware preprocessing. We examine how these combined strategies improve resilience and accuracy in real-world scenarios. The findings contribute to building more secure and adaptable classification frameworks capable of withstanding modern adversarial tactics. In fact, CNNs have proven especially effective. Their ability to process large-scale datasets, detect subtle structural variations, and automate the threat detection pipeline has made them critical assets in security infrastructures [

4]. Whereas conventional methods relied on signature matching, CNNs support more generalized defenses by learning discriminative features directly from raw data. Their effectiveness, however, depends heavily on the presence of meaningful, consistent training patterns. An aspect this research directly addresses through careful dataset construction.

Nevertheless, CNN-based systems face significant challenges when encountering obfuscated data. Techniques such as noise injection, contrast adjustment, or hybrid malware composition, where features from multiple families are combined, can confuse even advanced models, leading to misclassification or accuracy loss [

3]. This structural obfuscation blurs class boundaries and exposes weaknesses in learned representations. To mitigate this, our research highlights the importance of robust preprocessing, particularly the application of robust hashing methods that preserve image structure while counteracting obfuscation effects [

5]. By integrating this resilient type of hashing with state-of-the-art CNNs, we aim to improve the reliability of malware classification in adversarial and obfuscated conditions.

This paper is organized as follows. To contextualize our contributions, we begin in

Section 2 by reviewing relevant literature on malware classification, robust hashing, and adversarial resilience in CNN-based models.

Section 3 then provides the technical groundwork for our approach. In

Section 4, we introduce our salting technique and robust hashing pipeline, detailing the design rationale and implementation steps used to generate obfuscated malware variants.

Section 5 describes the experimental setup and evaluation metrics employed to assess performance across multiple configurations.

Section 6 presents our key findings, highlighting the impact of robust hashing and varying levels of salting on CNN classification accuracy and robustness. Finally,

Section 7 summarizes the implications of our results, and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work

In the realm of malware classification, a significant body of research has explored various machine learning and deep learning techniques to overcome limitations of traditional signature-based detection systems. The study in [

3] addresses the challenge of detecting polymorphic malware by employing machine learning classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests, and Decision Trees. Their analysis of feature and behavioral data revealed that Random Forest achieved the highest precision of 0.92. Extending this, the comparative study in [

6] investigates the effectiveness of deep learning versus machine learning approaches on a multiclass classification problem involving nine malware families. This work underscores the impact of obfuscation on accuracy and finds that deep neural networks perform best, achieving 95.9% accuracy, while Random Forest performs poorly under feature overlap.

Another notable framework integrates dynamic analysis using the Cuckoo Sandbox to extract API call features and applies a two-stage feature selection mechanism (Chi-Square and Random Forest-based selection), reducing the feature space from 42,000 to 87 [

7]. Their Decision Tree classifier reached an impressive 99.11% accuracy in both binary and multiclass tasks. Shifting towards visual representation, the study in [

8] proposes converting malware binaries into grayscale images and classifying them using a ResNet-50 CNN, achieving 94.03% accuracy on the Malimg dataset. This approach demonstrates the potential of image-based malware detection, especially against polymorphic and metamorphic malware.

Entropy-based techniques are explored in [

9], where a one-dimensional CNN model leverages entropy levels to detect obfuscated malware. This method is particularly effective in differentiating between obfuscated and non-obfuscated samples based on entropy thresholds. Addressing dataset imbalance and real-time classification, the study in [

10] builds a Streamlit-based web application for malware classification. Their CNN-based model not only performs robustly across different malware types but also surpasses models like ResNet-50 with an accuracy of 98.3%.

Finally, recognizing the limitations of deploying heavy models on resource-constrained IoT devices, a recent study proposes a lightweight CNN architecture optimized using filter pruning, 1x1 convolutions, batch normalization, dropout, and Bayesian tuning [

11]. Despite being computationally efficient, the model maintains high accuracy (98.85%) on the Malimg dataset, emphasizing its practicality for embedded environments. Collectively, these studies contribute critical insights into the design, optimization, and deployment of effective malware detection systems, particularly emphasizing robustness against obfuscation, resource efficiency, and high classification accuracy across diverse malware families.

Recent literature has explored various approaches to enhancing the robustness of image-based malware classification models, particularly under adversarial and obfuscated conditions. Early efforts compared traditional feature-based methods, such as gist descriptors combined with k-Nearest Neighbors and SVM, to deep learning techniques that leverage grayscale representations and transfer learning frameworks [

12]. While both approaches achieved high classification accuracy, deep learning models offered improved scalability and inference speed, with greater resilience against obfuscation. Subsequent studies examined the comparative performance of deep learning and simpler static feature-based classifiers, revealing that while k-NN outperformed deep learning models in some scenarios, the latter demonstrated superior generalization in zero-day evaluations [

13].

In parallel, robust image hashing methods, such as wavelet-based and distributed coding techniques, have been proposed as efficient alternatives to conventional machine learning, providing flexible update mechanisms with competitive accuracy [

5]. Additionally, researchers have investigated the impact of salting-based obfuscation on CNN classifiers, highlighting significant accuracy degradation when models are exposed to adversarially modified datasets [

14].

These studies underscore the evolving landscape of resilient malware classification and emphasize the need for scalable, generalizable approaches in adversarial contexts.

3. Background

This research explores the integration of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) with robust hashing techniques to strengthen malware detection, aiming to enhance resistance against evasion tactics and improve cybersecurity defenses. In this section, we provide a brief overview of the underlying mechanisms of robust hashing, CNNs, and dataset obfuscation.

3.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are advanced deep learning architectures specifically developed for image and visual data analysis. CNNs typically consist of convolutional layers that apply filters to capture important visual features, pooling layers that summarize these features and reduce spatial dimensions, and fully connected layers responsible for making the final classification decisions [

15]. CNNs are widely recognized for their effectiveness in tasks such as image recognition, object detection, and feature extraction due to their ability to automatically learn hierarchical visual features [

15].

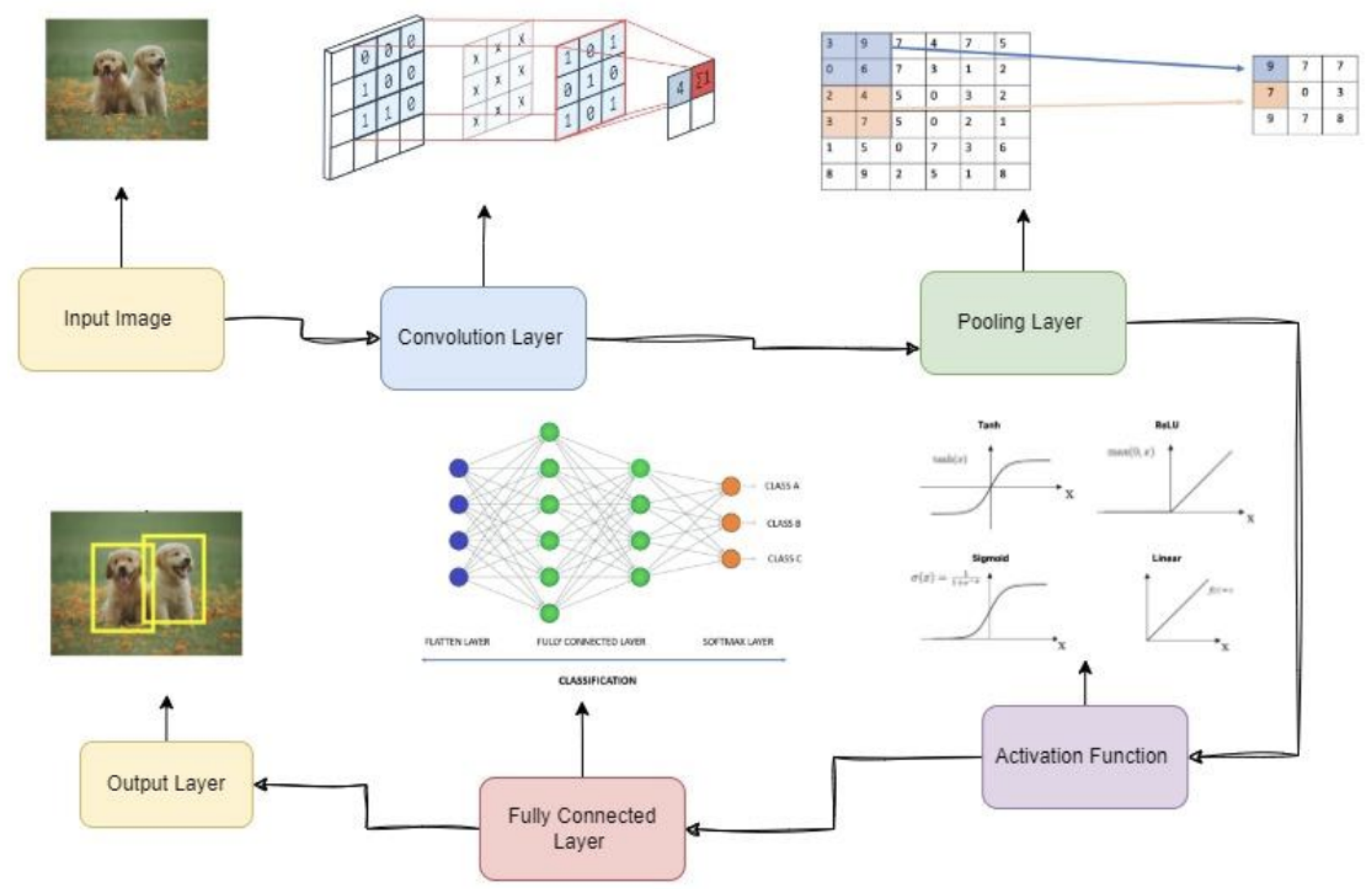

Figure 1 [

16] shows the architecture of a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) designed for image classification. The following outlines the function of each layer within the CNN:

Input Image: The network begins with an input image; in this example, an image of a dog is used.

Convolutional Layer: The first layer performs convolution operations on the input image [

17]. It extracts features such as edges, textures, and patterns by applying various filters or kernels, producing a set of feature maps.

Pooling Layer: This layer reduces the spatial dimensions of the feature maps, which lowers computational complexity and mitigates overfitting through dimensionality reduction [

17].

Activation Function Layer: Following convolution, a nonlinear activation function is applied, typically the rectified linear unit (ReLU) [

17].

Fully Connected Layer: After a series of convolutional, activation, and pooling layers, the feature maps are flattened into a one-dimensional vector and passed through fully connected layers. These layers perform the final classification based on learned features [

15].

Output Layer: The final layer produces class probabilities. In the illustrated architecture, the network predicts whether the image corresponds to “Dog” or “Not Dog,” selecting the class with the highest probability as the output.

Figure 1.

CNN Architecture [

16].

Figure 1.

CNN Architecture [

16].

Figure 2.

CNN Models Used in this Research.

Figure 2.

CNN Models Used in this Research.

3.1.1. MobileNet

MobileNet is a lightweight convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture specifically designed for devices with limited computational power, such as smartphones and embedded systems [

18]. Its key innovation is the use of

depthwise separable convolutions, which decompose the standard convolution into two operations:

This architectural change significantly reduces computational cost and model size compared to traditional CNNs. In malware detection, MobileNet is particularly useful for enabling real-time inference on resource-constrained devices without a substantial loss in accuracy. Its efficiency makes it a practical choice for on-device cybersecurity solutions.

3.1.2. ResNet

Residual Networks (ResNets)represent a major advancement in deep CNN design [

19]. They address the

vanishing gradient problem that hampers the training of very deep networks. ResNets introduce residual (skip) connections, which allow the input of a layer to bypass one or more subsequent layers and be added directly to the output.

These residual connections help maintain information flow during backpropagation and allow networks to be significantly deeper without degradation in performance. In the context of malware detection, ResNets can learn complex, high-level representations from malware image data, thereby improving the accuracy of detection systems.

3.1.3. DenseNet

Dense Convolutional Networks (DenseNets) are another CNN variant characterized by

dense connectivity: each layer receives the feature maps of all preceding layers as additional inputs [

20]. This structure encourages feature reuse, improved gradient flow, and parameter efficiency.

As a result, DenseNets are often more compact and computationally efficient while maintaining high performance. In malware detection applications, DenseNets have demonstrated strong performance due to their ability to model complex patterns with relatively fewer parameters, making them well-suited for environments with limited resources.

3.2. Robust Hashing

Robust hashing involves specialized image-processing techniques that produce compact and invariant representations of visual data [

5]. These methods generate stable hash codes that remain consistent under minor transformations such as rotation, scaling, noise, or pixel-level modifications [

21].

By contrast, traditional hashing techniques, widely used in cryptography, convert input data into fixed-size hash values to verify data integrity, authenticate transmissions, and detect tampering [

22,

23]. A core principle in cryptographic hashing is collision resistance, that is, the deliberate design to avoid generating identical hash outputs for different inputs [

14]. While such sensitivity is desirable in secure communications, it becomes problematic in contexts like malware classification, where obfuscation should not yield entirely divergent representations.

To address this mismatch, our research applies robust hashing, a method that generates similar hash values for visually or structurally related inputs, even if they differ at the byte level [

14]. This property is especially beneficial for malware detection, as binaries from the same family often vary partially due to packing or obfuscation techniques. Robust hashing enables classifiers to identify structural similarities, improving generalization across obfuscated variants.

In this domain, robust hashing histograms are critical to preserving consistency under adversarial manipulation, such as subtle image perturbations intended to evade detection [

5,

24]. By focusing on invariant visual features, these techniques bolster the resilience and reliability of CNN-based malware classifiers in adversarial settings.

One of the key challenges in malware image classification is handling the size and complexity of malware binaries. Converting entire binaries directly to fixed-size images can lead to a loss of important structural features, especially when large files are forcibly resized to small dimensions like 256×256. Moreover, many malware families produce visually similar binaries, increasing the risk of misclassification. Robust hashing mitigates these issues by focusing on distributional features that persist in similar variants. It allows the model to focus on invariant patterns and structure, rather than being misled by small, inconsequential differences introduced by obfuscation.

Details on how robust hashing was applied in this research can be found in

Section 4.3.

4. Methodology

This section outlines the foundational components of our experimental framework, beginning with a description of the malware dataset used in this study. We then detail the obfuscation strategies applied to simulate adversarial conditions and evaluate model robustness. Finally, we introduce the robust hashing technique employed to generate invariant visual representations of malware samples, enabling improved classification performance under varying levels of obfuscation. Together, these subsections establish the data and preprocessing pipeline that supports our investigation into resilient CNN-based malware detection.

4.1. Dataset

The dataset used in this research consists of approximately 40 GB of malware executable files, curated specifically for static analysis and machine learning-based threat detection. A major challenge in handling this dataset was the substantial variation in file sizes: individual samples ranged from a few kilobytes (KB) to large executables exceeding 32 megabytes (MB). This broad spectrum necessitated specialized preprocessing strategies to ensure consistency across feature extraction and model training pipelines.

The primary preprocessing step involved converting the malware binaries into images, as this research focuses on image-based analysis. Since the files were in raw binary format, each binary file was transformed into a grayscale image of fixed dimensions (256×256 pixels). This process began by reading each binary file byte-by-byte into a NumPy array using a Python-based approach. The byte array was then reshaped into a 2D image. In cases where the total number of bytes was insufficient, zero-padding was applied to achieve the desired dimensions. The resulting image was saved in PNG format and stored in a dedicated directory, forming the initial image dataset.

Subsequently, the dataset was organized into different malware families based on their respective labels. This was achieved by mapping each image filename to its corresponding class using a label file containing metadata on sample names and their associated malware families. Each image was checked against this label file, and if a match was found, the image was moved into a folder named after the appropriate malware family. To prevent duplication, the preprocessing pipeline included a check to retain only one instance of duplicate filenames. The final dataset consisted of 20 distinct malware families with approximately 14,000 images in total.

However, representing large binaries within a fixed 256×256 pixel format meant that only a portion of the file could be visualized, possibly omitting critical structural features. This loss of information posed additional challenges for the learning models, as they had to identify patterns from truncated or incomplete representations. Moreover, some malware families exhibited strong visual similarity, while others were highly random or noisy, making classification more difficult. These factors, combined with class imbalance and reduced file content in image form, highlighted the need for robust feature extraction methods. To address this, we employed robust hashing techniques, described in

Section 4.3.

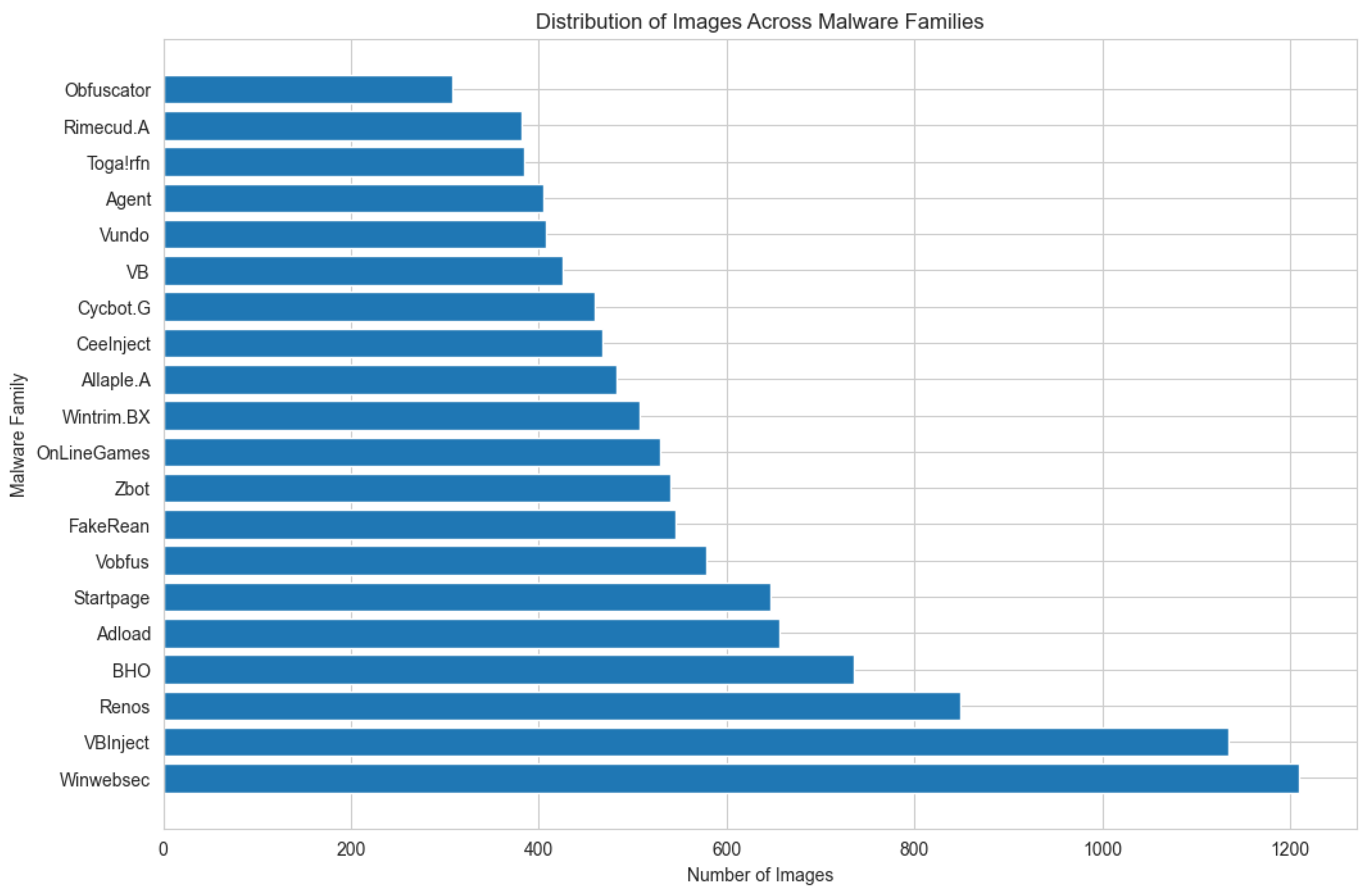

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of images across malware families in the dataset. Each bar in the chart represents a malware family, and the bar length indicates the number of image samples belonging to that family. This visualization clearly highlights the issue of class imbalance: certain families, such as

Cybots.G,

Toga!rfn,

Winwebsec, and

VBInject, contain a significantly larger number of samples compared to others. This imbalance can adversely affect the performance of machine learning models, which may become biased toward more prevalent classes [

25].

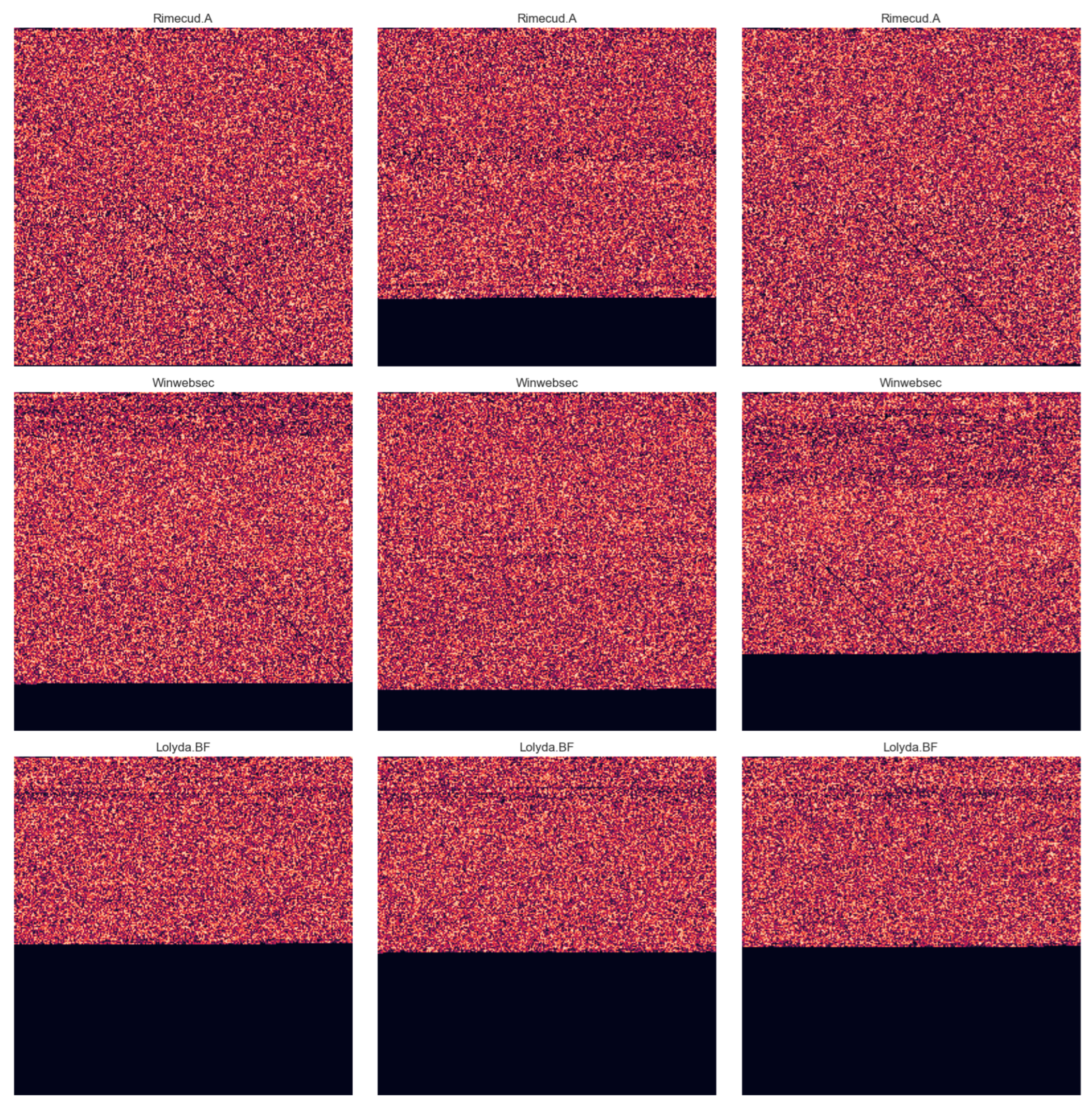

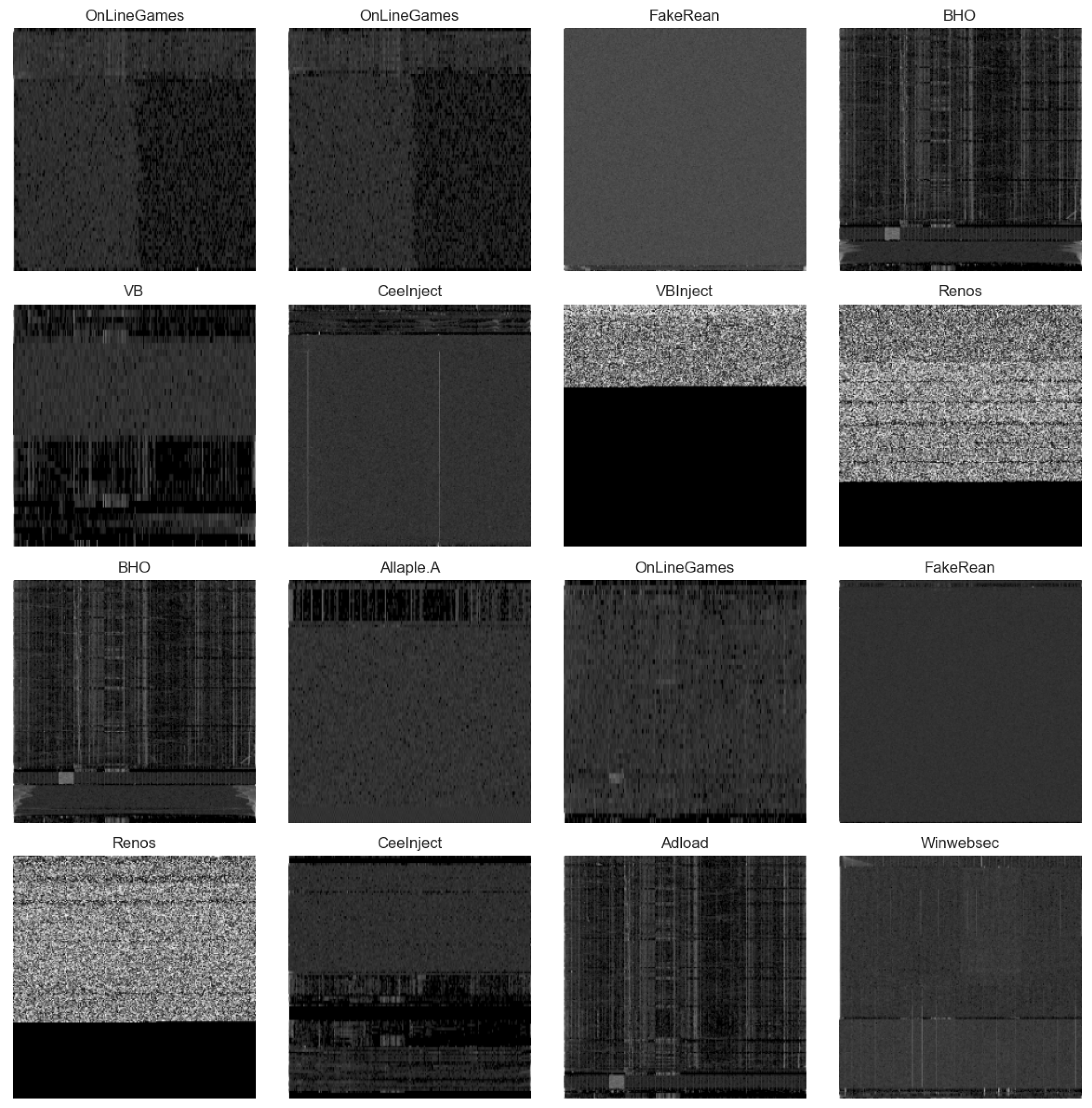

To provide insight into the structure of malware images,

Figure 4 presents representative samples from several families. These images were generated by converting the raw binary content of the malware files into grayscale images. Patterns within these images often reflect family-specific characteristics; for instance, families like

OnLineGames and

BHO exhibit noticeable horizontal and vertical structures, whereas families such as

Winwebsec appear more chaotic, with random pixel distributions. These visual traits provide informative cues that machine learning models can exploit to differentiate between malware types.

A more detailed side-by-side comparison is shown in

Figure 5, where multiple families are visually compared to highlight inter-family differences. This visual comparison underscores the variation in binary structure when rendered as images. For example, families like

Renos tend to display more regular and distinguishable patterns, whereas others, such as

Winwebsec, are dominated by visual noise. Notably, since all binary files are mapped to a fixed 256×256 resolution, some larger files may be truncated during image conversion, potentially omitting structural features that are important for classification. This limitation highlights the challenge of capturing representative content from binaries of varying sizes.

Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of the updated malware image distribution across 20 families used in this study. The final dataset comprises nearly 14,000 images across 20 distinct families, after filtering for class balance and removing duplicates. The differences in visual complexity between malware families and the variability in sample sizes emphasize the need for robust feature extraction techniques, such as the hashing methods, to ensure accurate and generalizable classification.

4.2. Dataset Obfuscation

Traditional image processing techniques often involve obfuscation methods such as noise addition, blurring, or rotation [

26]. These are typically employed to simulate real-world variability and protect models against unauthorized recognition. However, in the domain of malware analysis, obfuscation is applied at the file level rather than at the visual or image level.

To replicate adversarial behaviors and evaluate the resilience of CNN classifiers, this study employs file-level obfuscation techniques that emulate strategies commonly used by malware authors [

27]. These include code encryption, insertion of redundant instructions, and packing executables into varied formats. Instead of directly modifying the source malware code, the obfuscation is simulated during pre-processing using a technique known as

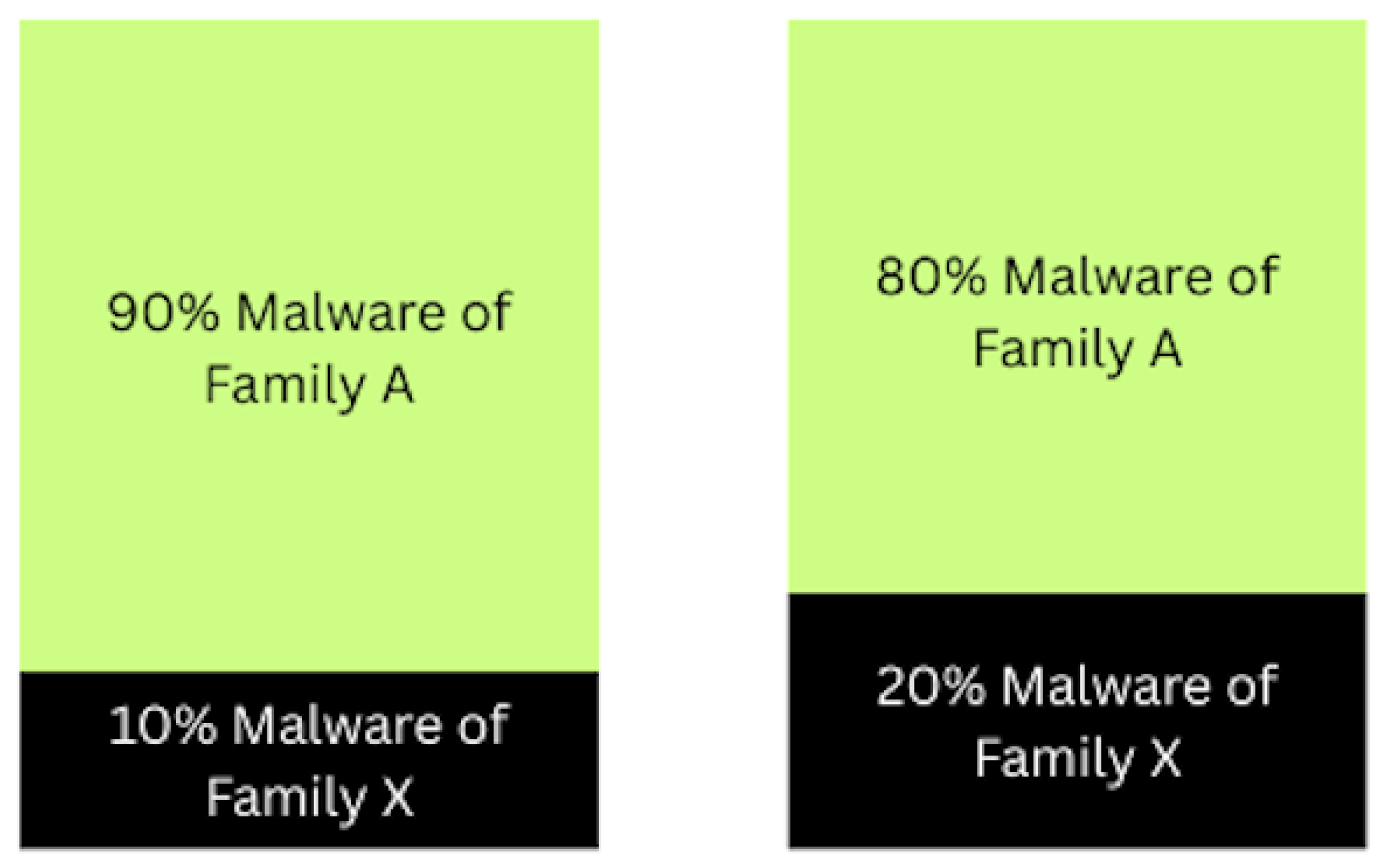

salting. This process blends code segments from two distinct malware samples to generate a novel, more complex variant. Such fusion is intended to challenge the CNN’s ability to distinguish between malware families by simulating obfuscated conditions. This setup enables an assessment of whether robust hashing techniques enhance classification accuracy and resilience in the presence of adversarial noise.

Figure 6 illustrates the salting technique, which merges one malware file from the primary family with a randomly chosen file from another family. The resulting hybrid sample contains a dominant portion from the primary family and a smaller segment from the secondary, simulating a fused or polymorphic variant. This process enables an evaluation of model performance under adversarial obfuscation, and facilitates an investigation into the tolerance of the CNN classifier to increasing levels of salting. Specifically, our objective is to determine how much salting can be introduced before the classification accuracy degrades beyond acceptable thresholds.

The random salting procedure applied to malware binary files consists of the following steps:

Salting Ratio: 90% of the final salted sample is derived from the primary malware, while 10% is the adversarial sample, resulting in a salting ratio of 0.1.

Image Size: The combined binary data is reshaped into a grayscale image of size (65,536 bytes).

Majority and Minority Bytes: Byte segments are proportionally extracted from the primary and secondary malware samples.

Salting Process: Each primary malware file is randomly paired with a file from a different family. 90% of the data is taken from the primary file, while 10% is taken from the secondary. The minority portion is randomly positioned to avoid padded regions commonly found at the start of binary files.

Output: The resulting salted sample is saved as a grayscale PNG image.

The salting technique enables the creation of realistic and diverse malware representations, allowing CNN models to be evaluated against more adversarial inputs. Together with robust hashing, this obfuscation strategy forms the foundation for the experimental framework described in the next section.

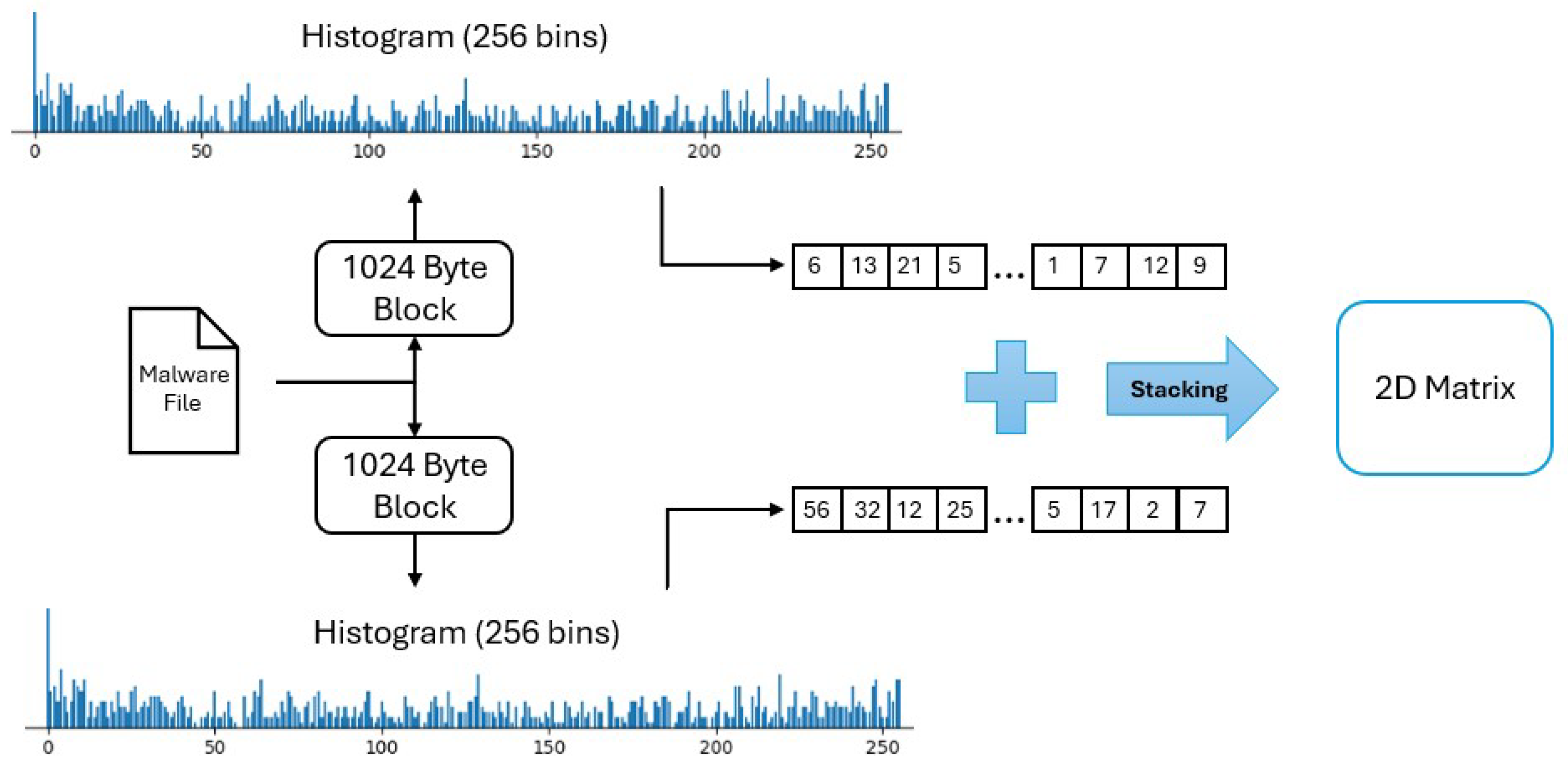

4.3. Robust Hashing for Malware Classification

In this project, robust hashing is used to convert malware binaries into two-dimensional image representations, enabling CNN-based models to identify visual patterns. The specific hashing method used is histogram hashing, which creates a compact visual fingerprint by summarizing byte frequency distributions across segments of the binary file. As shown in

Figure 7, the process begins by splitting each binary file into fixed-size blocks of, for example, 1024 bytes (1KB). For each block, simply two in the Figure example, the frequency of byte values (ranging from 0 to 255) is computed to form a histogram. These histograms are then stacked to create a two-dimensional matrix. The resulting image becomes the robust hash, a visual representation that captures structural characteristics of the binary while remaining resilient to minor alterations.

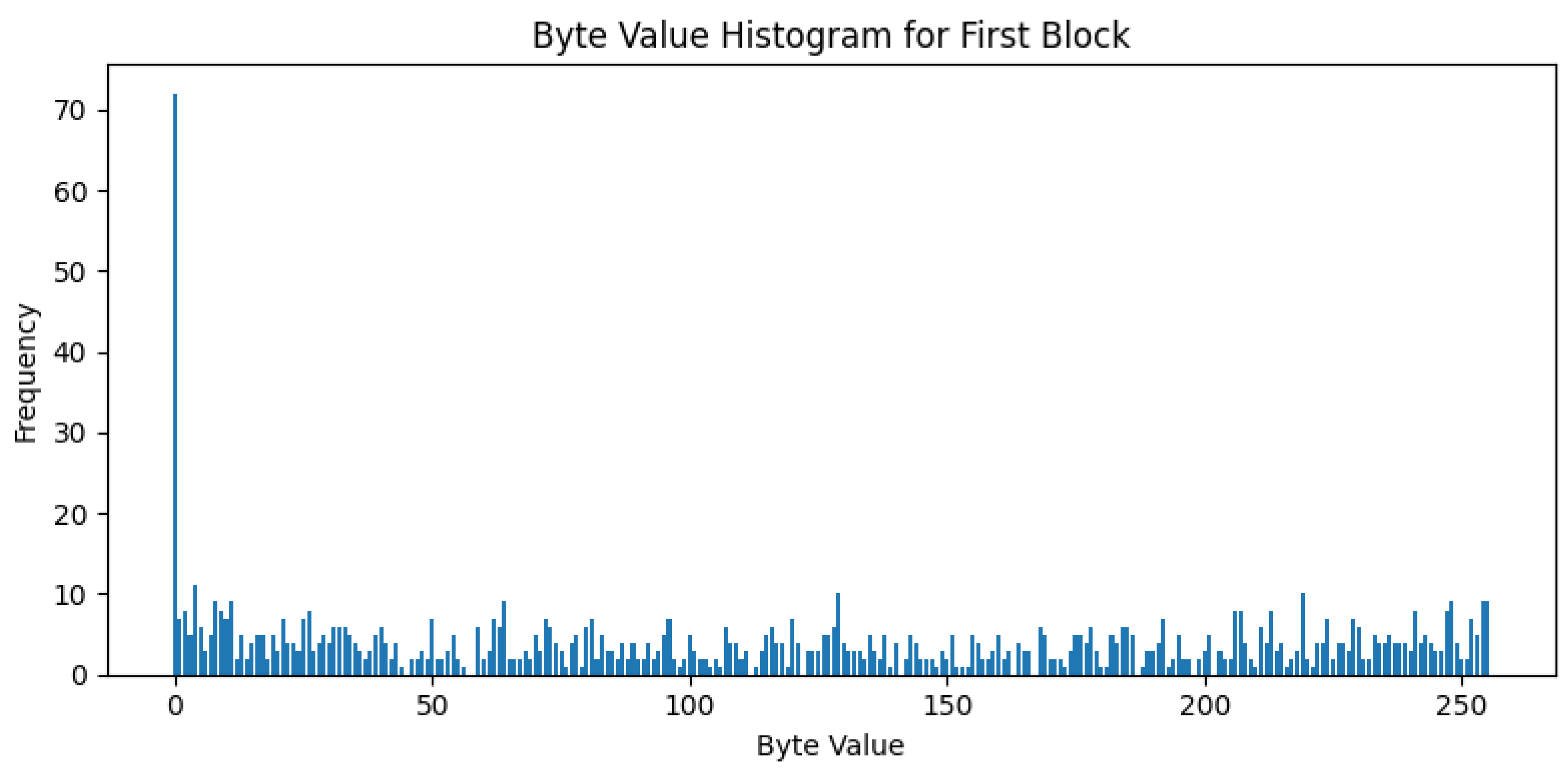

Figure 8 illustrates the histogram for the first block of a malware file. The x-axis denotes byte values (0–255), while the y-axis indicates the frequency of each byte value in the block.

These two-dimensional matrices, composed of histograms from each block in the binary file, are normalized such that each row sums to 1 and then resized to a fixed 256×256 image. It is important to note that the resulting image dimensions can vary depending on the number and size of blocks. To ensure consistent image size across samples, regardless of the input file’s length, the block size may be adjusted dynamically for each file. Gamma correction is then applied to enhance image contrast and highlight subtle patterns. In our experiments, we found the gamma value 0.4 to be the best choice. The final output is a grayscale image representing the malware’s robust hash.

Here a summary of the key steps in the robust hashing process:

Input: Raw binary malware files from the dataset.

Block-wise Histogram Calculation: Byte frequencies (0–255) are computed for each fixed-size block of the binary file.

Matrix Formation: Histograms from all blocks are stacked to form a 2D matrix.

Normalization: Each row of the matrix is scaled to sum to 1.

Resizing: The histogram matrix is resized to a 256×256 image to standardize input for CNN models.

Gamma Correction: Applied to enhance contrast and bring out subtle visual features (gamma = 0.4).

Output: Final PNG images representing robust hashes, ready for classification.

5. Experiments

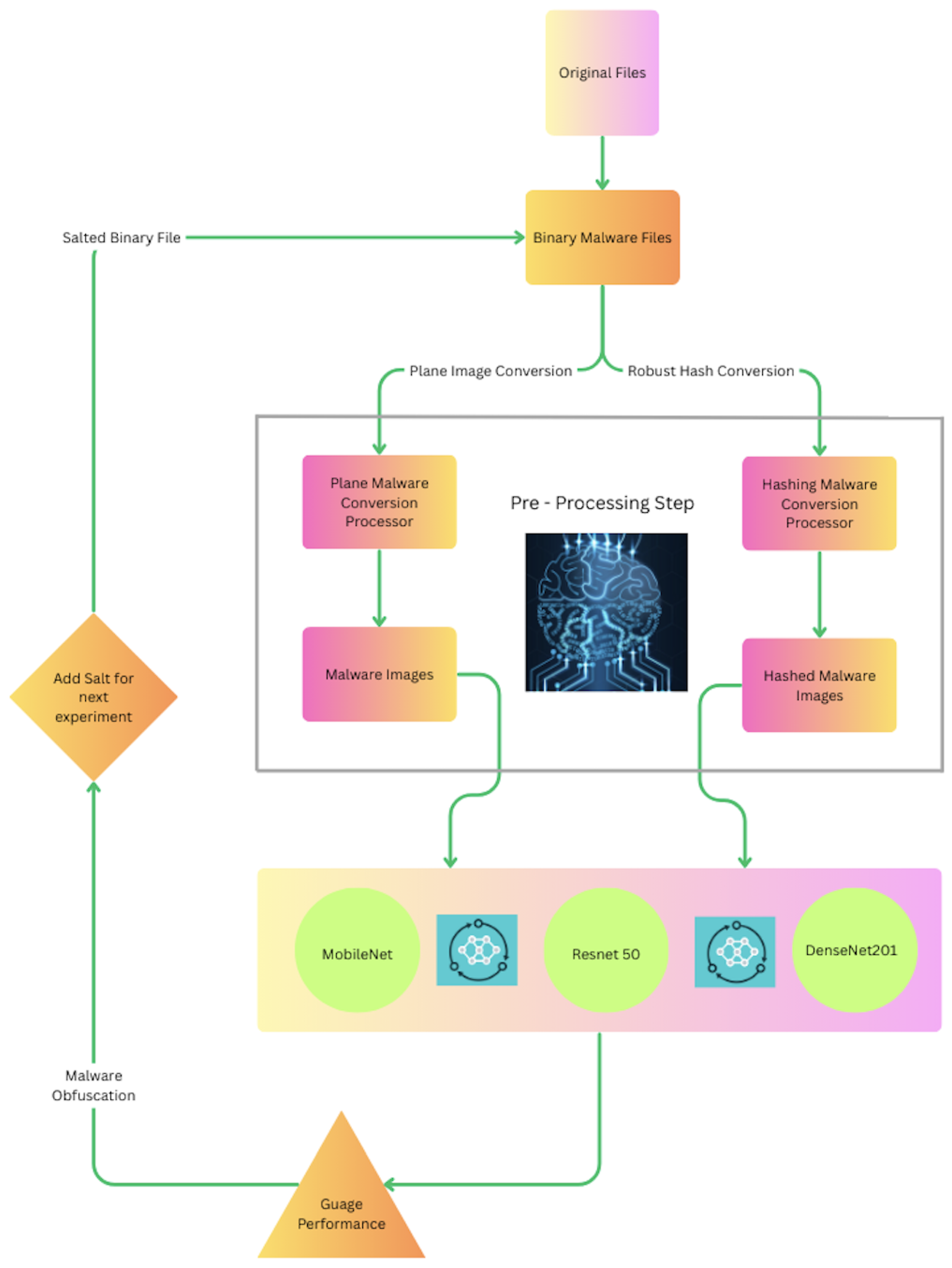

This research focuses on evaluating the performance of advanced CNN models, enhanced by robust hashing, on both obfuscated and non-obfuscated malware datasets. As outlined in

Figure 9, each experiment began with binary malware files being converted into image representations using two distinct methods. The first involved a direct plane conversion using the Python Imaging Library (PIL), while the second utilized robust hashing to produce more consistent and semantically meaningful feature mappings. These malware images were then fed into CNN models to assess classification performance.

Initial experiments on the non-obfuscated dataset, that is, converted directly to image format without hashing, yielded a classification accuracy of 71% in multiclass settings, where the CNN was tasked with assigning samples to one of 20 malware families. Applying the same CNN models to non-obfuscated images generated via robust hashing, instead, led to a nearly 20% increase in classification accuracy, along with improvements in the model loss value and both training and validation performance. These findings demonstrate that robust hashing substantially enhances CNN effectiveness in malware classification tasks.

Subsequent experiments focused on obfuscated datasets. Obfuscation was performed using a salting approach, which fused binary data from multiple malware families. Two types of image conversions were used: one involved hashing prior to salting, while the other employed standard PIL conversion. Experiments were repeated across five salting ratios, 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%, each representing the proportion of data derived from the adversarial malware family. Models were tested with both obfuscation strategies to evaluate robustness under adversarial conditions.

Three advanced CNN architectures were utilized: MobileNet, ResNet, and DenseNet. Each configuration was assessed in two phases, without hashing, and with hashing, on both obfuscated and non-obfuscated datasets. The dataset was split using a 70-15-15 ratio for training, validation, and testing, respectively, to ensure balanced generalization. Transfer learning was employed, leveraging pre-trained ImageNet weights to accelerate convergence and minimize training data requirements.

Images were resized from to pixels to align with the input dimensions of pre-trained models. Experiments were conducted using a batch size of 128, with the Adam optimizer applied to dynamically adjust learning rates. Training was limited to a maximum of 50 epochs, and early stopping was triggered after three consecutive epochs without improvement to prevent overfitting. Categorical crossentropy was chosen as the loss function, suitable for multi-class classification, and accuracy served as the primary evaluation metric.

To further explore feature dimensionality, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was tested. However, PCA did not yield improvements, as the CNN models already incorporate internal feature extraction and dimensionality reduction through their convolutional layers. Applying PCA post-feature extraction removed critical information and introduced redundancy, reinforcing the sufficiency of built-in model architectures for this task.

A comprehensive summary of the experimental phases includes:

CNN evaluation on non-obfuscated data without hashing.

CNN evaluation on non-obfuscated data with robust hashing.

Experiments on obfuscated datasets using both hashed and standard image conversions.

Application of five salting ratios: 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%.

Testing across MobileNet, ResNet, and DenseNet models.

Each configuration repeated twice for validation and reliability.

6. Results

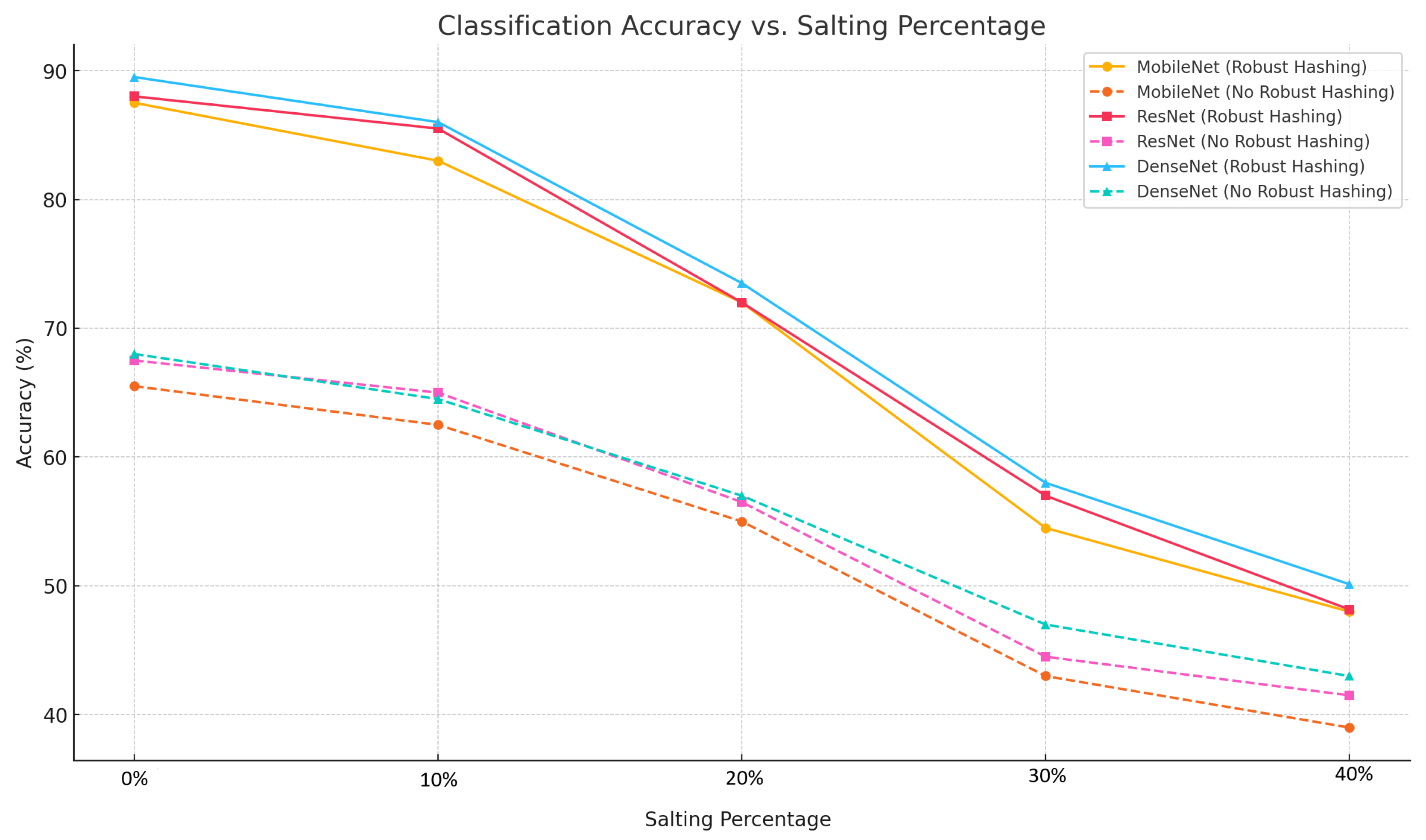

The experimental results, derived from testing MobileNet, ResNet, and DenseNet models under five salting conditions (0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%), demonstrate the tangible impact of robust hashing on malware classification accuracy. Each model was evaluated both with and without the robust hashing technique. The results consistently show that robust hashing improves model accuracy across varying levels of dataset obfuscation.

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 present accuracy comparisons under different salting ratios. The models achieved their highest performance on the unsalted data (0%), with DenseNet reaching an accuracy of 89.50% when robust hashing was applied, compared to 68.00% without it. As salting increased, accuracy declined across all models, but the presence of robust hashing consistently mitigated this drop. For example, at 40% salting, DenseNet still maintained a 7.13% improvement over its non-hashed counterpart.

Figure 10 illustrates the trend in model accuracy as salting levels increase, further confirming that while accuracy decreases with heavier obfuscation, robust hashing mitigates this drop consistently.

Figure 10 visualizes this trend, confirming that while obfuscation degrades model performance, robust hashing provides a stabilizing effect.

Table 7 summarizes average performance across all salting levels, with MobileNet demonstrating the most consistent gains, averaging a 16.00% improvement, while DenseNet achieved the highest overall classification accuracy at 71.43%. Compared to MobileNet and ResNet, DenseNet exhibited superior resilience, particularly under moderate to high obfuscation conditions.

Overall, these results validate the effectiveness of robust hashing in preserving discriminative features and enhancing CNN-based malware classification under diverse obfuscation conditions.

7. Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of histogram-based robust hashing applied at the byte level in enhancing CNN-based malware classification under adversarial obfuscation. Through systematic evaluation of MobileNet, ResNet, and DenseNet architectures across five salting conditions (0% to 40%), we show that robust hashing consistently improves classification accuracy, even as dataset complexity increases due to obfuscation. DenseNet, in particular, exhibited superior performance and resilience, maintaining high accuracy across all test cases and demonstrating robustness beyond the 10% salting threshold.

The results confirm that while obfuscation degrades model performance, robust hashing mitigates this effect by preserving discriminative structural features. These findings underscore the value of robust hashing as a preprocessing strategy for malware detection, particularly in adversarial settings where traditional byte-wise representations may fail.

Future work can explore adaptive salting thresholds by dynamically adjusting the perturbation intensity based on malware family characteristics or classifier confidence levels. For instance, applying stronger salting to polymorphic malware like Vobfus or Zbot, which exhibit high evasion rates. Researchers can also integrate explainable AI techniques, such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), to interpret model decisions under obfuscation and reveal which image features contribute most to classification outcomes, even when adversarial noise is present. Additionally, the evaluation can be extended to real-world malware datasets with dynamic behaviors, such as those captured via sandbox execution or behavioral logging tools like Cuckoo Sandbox, to assess model robustness against evolving threats and time-dependent attack patterns

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this article can be found at

https://.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kramer, S.; Bradfield, J.C. A general definition of malware. Journal in computer virology 2010, 6, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kane, P.; Sezer, S.; McLaughlin, K. Obfuscation: The hidden malware. IEEE Security & Privacy 2011, 9, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J, M.P.; C D, A.; AS, A.; B. R, S.P.; S.M, R. Malware Detection using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 Second International Conference on Advances in Information Technology (ICAIT), 2024, Vol. 1, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S.A.; Alshurideh, M.; Elnagar, A.; Shaalan, K. Machine learning and deep learning techniques for cybersecurity: a review. In Proceedings of the The International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision. Springer, 2020, pp. 50–57.

- Huang, W.C.; Di Troia, F.; Stamp, M. Robust Hashing for Image-based Malware Classification. In Proceedings of the ICETE (1); 2018; pp. 617–625. [Google Scholar]

- Bokolo, B.; Jinad, R.; Liu, Q. A Comparison Study to Detect Malware using Deep Learning and Machine learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (BDAI); 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, K.; Kumar, R.; Sethi, L.; Bera, P.; Patra, P.K. A Novel Machine Learning Based Malware Detection and Classification Framework. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security); 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhesa, R.A. ; Hendrawan. In ; Ismail, S.J.I. Classification of Malware Using Machine Learning Based on Image Processing. In Proceedings of the 2021 15th International Conference on Telecommunication Systems, Services, 2021, and Applications (TSSA); pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Okubo, S.; Kimura, T.; Cheng, J. Entropy-Based Malware Detection Using One Dimensional CNN. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Consumer Electronics - Taiwan (ICCE-Taiwan); 2024; pp. 763–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebish, M.W.; Awni, M. CNN-Based Malware Family Classification and Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEENG). IEEE; 2024; pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Chang, T.S.; Chang, Y.C. A Malware Detection and Classification System Based on Lightweight CNN Model. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE); 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajamanam, S.; Selvin, V.R.S.; Di Troia, F.; Stamp, M. Deep Learning versus Gist Descriptors for Image-based Malware Classification. In Proceedings of the Icissp; 2018; pp. 553–561. [Google Scholar]

- Bhodia, N.; Prajapati, P.; Di Troia, F.; Stamp, M. Transfer learning for image-based malware classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.11551, arXiv:1903.11551 2019.

- Tran, K.; Di Troia, F.; Stamp, M. Robustness of image-based malware analysis. In Proceedings of the Silicon Valley Cybersecurity Conference. Springer; 2022; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.J.; Turko, R.; Shaikh, O.; Park, H.; Das, N.; Hohman, F.; Kahng, M.; Chau, D.H.P. CNN explainer: learning convolutional neural networks with interactive visualization. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2020, 27, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taye, M.M. Theoretical understanding of convolutional neural network: Concepts, architectures, applications, future directions. Computation 2023, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. Journal of big Data 2021, 8, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, D.; El-Sharkawy, M. Thin MobileNet: An Enhanced MobileNet Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON); 2019; pp. 0280–0285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Liu, T.; Tao, D. Why resnet works? residuals generalize. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2020, 31, 5349–5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulazeez, F.A.; Ahmed, I.T.; Hammad, B.T. Examining the performance of various pretrained convolutional neural network models in malware detection. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.; Gérard, S.; Cabot, J. Robust hashing for models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Model Driven Engineering Languages and Systems, 2018, pp.

- Ramakrishna, M. Hashing practice: analysis of hashing and universal hashing. ACM SIGMOD Record 1988, 17, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albeshri, A. An image hashing-based authentication and secure group communication scheme for IoT-enabled MANETs. Future Internet 2021, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, R.; Koon, S.M.; Jakubowski, M.; Moulin, P. Robust image hashing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2000 International Conference on Image Processing (Cat. No.00CH37101), Vol. 3; 2000; pp. 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japkowicz, N.; Stephen, S. The class imbalance problem: A systematic study. Intelligent data analysis 2002, 6, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, D.E.; Rarameswaran, R.; Blough, D.M.; Franz, A.A.; Palmer, T.J. Data obfuscation: Anonymity and desensitization of usable data sets. IEEE Security & Privacy 2004, 2, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorca, D.; Ariu, D.; Corona, I.; Aresu, M.; Giacinto, G. Stealth attacks: An extended insight into the obfuscation effects on android malware. Computers & Security 2015, 51, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).