1. Introduction

Pre-competition workouts are modified in many ways to prepare players to reach peak form both physically and mentally. Properly structured training units with strategies for post-activation strengthening, ischemic preconditioning, thermoregulation, and carefully selected exercises can lead to improved performance during competition [

1]. Preparing athletes for competition in an optimal way is the main goal of both the coach and the player. Soccer is a team game with low and high intensity efforts dominating during the game. A player, depending on his position on the field, covers an average of 11-13 km during a match [

2,

3]. Unpredictable elements such as sprinting, sudden change of position on the field, sliding, jumping, and striking the ball require excellent fitness and motor preparation (speed, endurance, strength) and coordination. Achieving efficiency in the game and a low injury rate requires a proper training process. Sports training should include general development, targeted training, specialized training, and recovery [

4]. Whole-body WBC/PBC stimulation cryotherapy (cryostimulation) is considered an increasingly common therapy that can affect both the athlete’s health and performance [

5]. Deliberate lowering of tissue temperature and changes in blood flow result in reduced pain perception, improved well-being, and post-exercise recovery [

6,

7]. Cryostimulation is a form of cooling the body using low temperatures without causing tissue damage. The stimulus effect is achieved at temperatures below - 110⁰C, in a short time of 1-3 minutes. The purpose of cold stimulation is to induce systemic physiological responses to low temperatures. The body’s response is cooling, active congestion, redistribution of blood and modulation of hemodynamic indices of the cardiovascular system [

8]. Popularity of cryostimulation in sports medicine is growing rapidly, but few studies have addressed the acute and/or long-term effects of cryogenic temperatures on muscle performance. Several scientific reports address the effects of cryostimulation as a form of post-exercise recovery [

9,

10]. The purpose of the undertaken study was to evaluate whether a combination of low- and high-intensity training with five sessions of cryostimulation (PBC) would improve motor coordination, lower limb maximal power, and single movement speed in soccer players. It was also tested to determine whether PBC is safe when training for soccer competitions. To our best knowledge, this is one of the first studies to analyze the effects of PBC during two training periods on motor skills (power, speed, coordination) in soccer players.

2. Materials and Methods

Soccer players (n=24, age 21±4.9, height 181.7±7.7, weight 75.6±8.8, BMI 22.8±1.7) were recruited for the study. Football players voluntarily participated in the study and were informed about the study protocol, the risks of testing and research, and their rights in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Athletes completed written informed consent and had current certificates from a sports medicine doctor confirming their readiness to train. Study was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Karol Marcinkowski University of Medical Sciences in Poznań (Resolution No. 845/22) and entered in the Clinical Trials Register (ANZCTR of Australia and New Zealand, ACTRN; reference number 12622001541796). All athletes’ data were anonymized before randomization into a study group (with PBC cryosauna, n=11) and a control group (without CON cryosauna, n=12). One athlete did not complete the study due to lower respiratory illness. Participants were asked not to use other forms of recovery, cosmetic procedures, or any dietary supplements, nor consume alcohol or other stimulants during the study.

Inclusion Criteria. Age: soccer players aged between 18 and 35 years. Training Level: participation in regular soccer training for at least three years, with current involvement in competitive soccer. Health Status: no known musculoskeletal injuries, chronic diseases, or conditions affecting performance or recovery; medical clearance from a certified sports physician indicating readiness to participate in high-intensity training and cryostimulation procedures. Lifestyle restrictions: agreement to abstain from additional recovery therapies, cosmetic procedures, alcohol, stimulants, and dietary supplements during the study.

Exclusion Criteria. Age or Training Inexperience: under 18 or over 35 years old; less than three years of consistent soccer training or competitive play. Health Conditions: Acute or chronic injuries, cardiovascular diseases, or conditions that contraindicate cryostimulation; respiratory illnesses or other health issues that develop during the study. Non-Compliance: inability to adhere to the scheduled training, testing, or cryostimulation protocols; failure to follow lifestyle restrictions outlined in the study guidelines. Cryostimulation Contraindications: sensitivity or adverse reactions to cold exposure; previous adverse reactions to cryotherapy or similar treatments.

Study protocol

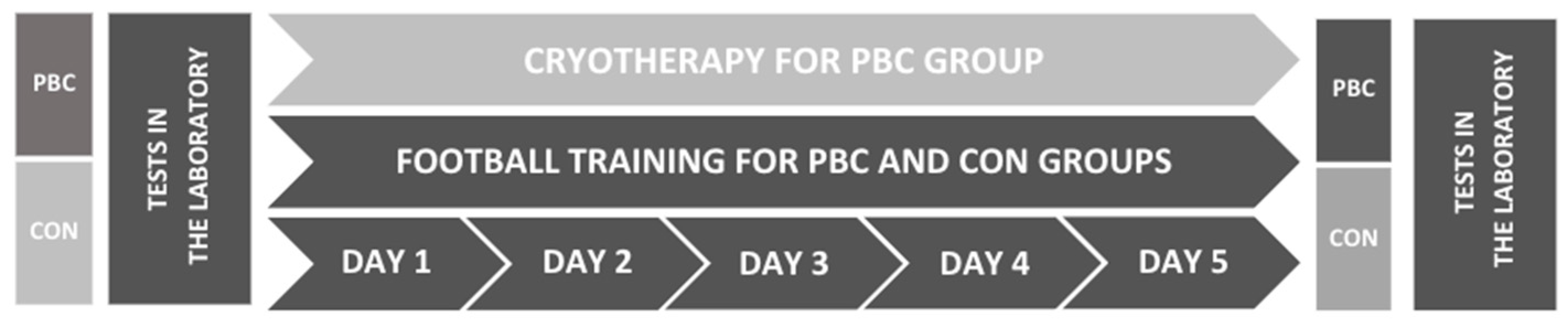

A randomized study was conducted during two training periods. The first stage of a 5-day cryostimulation procedure took place in November 2022, during the training period after the end of the league season. The second stage was conducted in January 2023, during the preparation period in full training loads. The sequence of procedures used in both stages was the same (

Figure 1). Before the application of cryostimulation, both PBC and CON groups underwent measurements: anthropometric using Tanita BC-418 MA analyzer (Medizin & Service GmbH, Germany), step frequency (tapping) and lower limb maximal power (jump with sweep, jump without sweep), Opto Gait optical system (MicroGate Timing and Sport, BONZAMO, Italy). Athletes in the PBC group, at the same hours of 8: 00 (stage I) and 17:00 (stage II), were subjected daily to cryostimulation in a JUKA cryosauna (model 0104-1, Germany). Both PBC and CON groups participated in training together throughout the study period. During the last 5 days of the experiment, repeat fitness tests and anthropometric measurements were performed (

Figure 1).

Anthropometric measurements

Using Tanita BC-418 MA analyzer, (Medizin & Service GmbH, Germany), measurement accuracy was ± 0.1 kg. The following parameters were analyzed: body mass index (BMI), total body water (TBW), fat mass (FM), and fat-free mass (FFM), and basal metabolism (BMR),

Table 1. All measurements were taken fasting at 8:00 a.m. on the first and fifth day of the study in both groups of subjects. The device was calibrated before each testing session according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Fitness tests

Measurements of step frequency and maximal power [W/kg] of the lower limbs were performed using the OptoGait optical system (MicroGate Timing and Sport, BONZAMO, Italy). The measurement system consisted of two panels used to detect spatial parameters for gait, jumping, and reaction time. Measurement strips were placed in parallel on the ground at a distance of 1.5 meters from each other. The test consisted of 3 parts: tapping (step frequency), maximal jumping up without upper limb sweep, and maximal jump up with upper limb assisted sweep (analysis of lower limb maximal power and jump height). Test subjects were positioned between the slats in the starting position, and performed 3 test trials, each trial began and ended with an audible signal, and the time of a single trial was 10 seconds. Analysis of the components of lower limb maximal power and step frequency was performed in the PBC and CON groups on the first and last days of the study.

Cryostimulation (PBC)

PBC protocol involved the participant being in a JUKA cryosauna (model 0104-1), for 3 minutes at - 140 ° C± - 20 ° C with the lid at shoulder height and the head over the chamber. The cryosauna was cooled with liquid nitrogen, and the temperature was monitored by a computer. Participants entered the cabin wearing clogs, wool socks, shorts, gloves, caps, and disposable PP non-woven masks to protect against inhalation of nitrogen fumes. The temperature inside the cryosauna was recorded at 30-second intervals using a sensor placed on the bottom of the cabin. The temperature of the room where the cryosauna was located was 21.0 ± 0.9° C, and the humidity of the air during the treatment was 35 ± 2, 0 % monitored with a QUIGG type LE 2014.14 moisture absorber. All participants received instructions on proper breathing and cryosauna behavior before the PBC procedure. They received information on risks, complications, and indications for immediate discontinuation of the therapy. Athletes signed an informed consent for the experiment. During the PBC, they remained in constant visual and auditory contact with the therapy supervisor. A cryostimulation session was performed every day from 8:00-9:00 am, for 5 days. During one PBC treatment, the athletes spent 3 minutes at -140° C ± 20° C. Each entry into the cryosauna was preceded by a measurement of saturation temperature and blood pressure. These measurements were taken again each day immediately after exiting the cryosauna. After completing the cryotherapy procedure, the athletes were subjected to a 15-minute warm-up according to a set schedule.

Training loads

During the period of the study, training loads included a transitional period (training bifurcation) after the end of the football season (7 days) and a preparatory period for the new league season (20 days). During the transition period, players were subjected to active recovery with low-intensity exercise. Efforts included stretching exercises, all-around gymnastics, rubber band and plyometric exercises, and various forms of team games. Between the two periods, the athletes had four weeks of active rest break, during which they exercised individually (walking, jogging, biking, swimming). The preparatory period, which included 1530 minutes, was aimed at developing selected conditioning motor skills: strength (740 minutes), endurance (420 minutes), and speed (370 minutes). The dominant factor was the high intensity of the applied training loads (80%), which were supplemented by training units dedicated to active recovery and the formation of playing technique (345 min. which accounted for 20% of the loads during this period). Each training session was preceded by a 10-15 minute warm-up. Strength training included circuit training, stability exercises on gym balls, squats, and exercises with medicine balls. Endurance training included continuous running at an intensity of 70-80% HR, MAS running for 6 min (15 s. run for 100 m., 15 s. break). Speed training included jumps, starts from various positions, reaction time to a signal, coordination ladder exercises, accelerations from a common start, and small games with a ball (

Table 2). During the preparatory period, the players played four control games.

Statistical analysisis

Analysis was performed using STATISTICA 13.3 (StatSoft Inc, Krakow, Poland). Mean and standard deviation were calculated for all parameters. The normality of the data distribution was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test. T-test for dependent samples was used to compare the results obtained by subjects in the same group before and after cryosauna application. A comparison of two groups at the same time was performed using the t-test for independent samples. The effect size for the independent t-test was calculated based on Cohen’s d test where 0.2-0.49 is a small effect, 0.5-0.79 is a moderate effect, and ≥ 0.8 is a large effect. The significance level for the tests was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

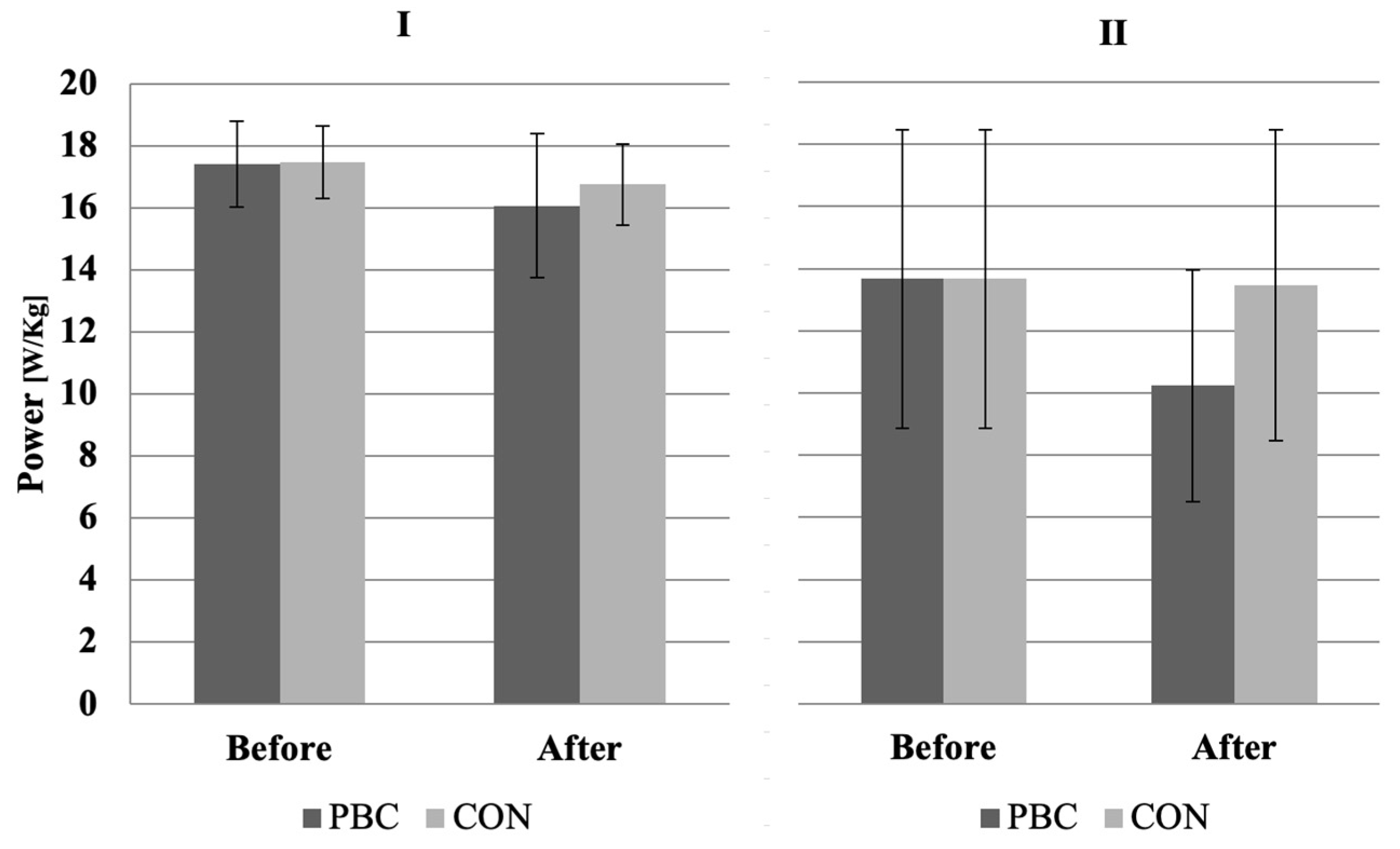

Results of the sweep jump test performed on the OptoGait platform in stage I of the study showed no significant differences in the measured parameters in both the PBC and CON groups. However, in stage II of the study, significant improvements were observed in jump height and maximum power generated in the PBC group. Stroke height in the PBC group before cryostimulation was 40.33 ± 4.14 and after the PBC intervention was 38.76 ± 3.84 (p = 0.0051, d Cohen = 0.39), as shown in

Figure 2 (

Figure 2.). Maximum power in the study group before PBC was 17.42 ± 1.20, and after 5 days of cryostimulation, it was 16.56 ± 0.93 (p = 0.0537, d Cohen = 0.81) (

Figure 3).

In the CON group, the results were not significantly different before and after PBC application (

Table 3).

Analyzing the results of the “jump without sweep” test from the first stage of the study showed no significant differences in the CON group in any of the measured parameters. In the PBC group, significant differences were observed in ground contact time and frequency. Foot contact time before cryostimulation was 1.93 ± 0.38, while after cryostimulation it was 2.33 ± 0.36 (p = 0.0068, d Cohen = 1.08). The frequency before the intervention was 0.43 ± 0.07 and after the intervention was 0.36 ± 0.05 (p = 0.0059, d Cohen = 1.17). In phase II of the study, repeating the “jump without a sweep” test, no significant differences were observed between trials performed before and after PBC in both the test group and CON in any of the measured parameters (

Table 4).

Results of the tapping test from Phase I of the study showed no difference in each of the measured parameters in the CON group (p>0.05). The PBC group, however, achieved improvements in parameters such as flight time, cycle rate, cycle, and frequency of lower limb movements. Flight time in the PBC group before cryostimulation was 0.08 ± 0.018, while after it was 0.071 ± 0.015 (p = 0.0264, d Cohen = 0.56). The rate of cycles before the intervention was 5.57 ± 0.67 and after the intervention 5.84 ± 0.63 (p = 0.0029, d Cohen = 0.42). Single cycle score before the use of 5-day cryostimulation was 0.85 ± 4.38, and after the use of PBC was 0.17 ± 0.01 (p = 0.0157, d Cohen = 0.31). Lower limb movement frequency increased from 113.55 ± 13.75 to 119.18 ± 13.20 after the intervention (p = 0.0029, d Cohen = 0.42). In stage II of the study, during the preparation period, the CON group did not achieve a significant improvement in any of the tested parameters of the tapping test (p>0.05), as in stage I (

Table 5). PBC group showed improvement in two measured parameters: foot-to-ground contact time and flight time. Foot-to-ground contact time before PBC application was 0.106 ± 0.023, while after it was 0.078 ± 0.019 (p = 0.05, d Cohen = 1.33). Flight time before intervention was 0.078 ± 0.015, while after intervention it was 0.062 ± 0.014 (p = 0.012, d Cohen = 0.97). Flight time in both stages is shown in.

4. Discussion

Study was conducted to analyze the effects of repetitive 5-day cryostimulation on coordination abilities, single movement speed, and maximal lower limb power, and as a supportive training element in soccer players in two training phases. There are many scientific reports on the effectiveness of cryostimulation of both WBC and PBC in supporting the repair and adaptive processes of the body subjected to exercise. Cryogenic temperature potential in regenerative processes has been described by many authors.

Our study showed that the PBC group in both training and preparation periods showed improvement in flight time (I stage 0,07 ± 0,02, II stage 0,062 ± 0,014,

Table 5) in two trials of the tapping test (fast running in place). We observed significant improvements in jump height 38,76 ± 3,84 and lower limb power (stage II, 16,56 ± 0,93, sweep jump,

Table 3) in the PBC group undergoing high-intensity training. A study by Hag et al. (WBC -120°C, 3 min) showed improved muscle strength after evaluating barbell squat, maximal isometric muscle torque, and countermovement jump in healthy male volunteers [

11]. We can observe contradictory results in a study by Vieira et al. (2015) (WBC, -110°C for 3 min), who evaluated global cryostimulation’s effect on athletes’ recovery capacity by assessing jump height and lower limb maximal power. WBC resulted in a significant decrease in both jump height and lower limb maximal power, but no significant differences were noted between groups [

12]. In the work of Mihailovic et al., they evaluated the parameter of maximum power in cyclists subjected to cryostimulation also not observing any effect of low temperature [

13]. Confirmation of the lack of significant changes that could indicate a beneficial effect of cryostimulation on lower limb maximal power was recorded by Dybek et al., (WBC, -130°C, 3 min). Effects of low temperature on aerobic capacity, anaerobic capacity, blood parameters, and lower limb power were evaluated [

14]. Jaworska et al. noted the effect of cryotherapy on improvement in the test of concentration and serving accuracy in a group of female volleyball players. This study shows that specific WBC-assisted retinal training increased levels of growth factors (IGF-1 and BDNF), but physical performance was impaired in response to cryostimulation [

15]. The use of PBCs prior to training may produce favorable results in controlled tests of physical fitness targeting training performance [

16]. The main findings of our experiment are that PBC did not interfere with force adaptation and did not cause deconditioning of soccer players. This procedure can be used during the preparatory phase of training, the period of de-training (inter-season breaks), and after the competitive season. Athletes can use repetitive PBC to aid in post-workout recovery. However, the potentially negative effects on muscle strength remain inconclusive. The limitation of the study was the small study group but given that the participants were relatively homogeneous in terms of age, training level, and type of sport, the size of our group was considered sufficient to draw conclusions. The temperature in the cryosauna was -130°C ± -20°C during exposure, which is common with prolonged use and any thermal stimulation [

17]. Protocol did not blind the trial due to the difficulty of masking cryogenic temperatures. In addition, the players were aware of the cold factor because they were given guidelines (how to prepare and behave in the cryosauna, limitations, and risks) before the experiment. Therefore, any information possessed by the participants could have influenced perceptual responses and PBC performance. A blinded randomized study would have to be conducted to negate any of these effects.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the potential benefits of partial-body cryostimulation (PBC) as a complementary training method for soccer players. Findings demonstrate that repeated PBC sessions, when combined with high-intensity training, can significantly improve motor coordination, jump height, and lower-limb power, particularly during preparatory training phases. These enhancements suggest that PBC may support key aspects of physical performance critical for soccer, including explosive strength and movement efficiency.

Importantly, PBC was found to be a safe and well-tolerated intervention, with no adverse effects reported by participants. Additionally, the procedure did not interfere with athletes’ concentration or training routines, indicating its feasibility as part of a structured training program. The potential to use PBC before competitions as a complementary strategy to traditional warm-up techniques offers practical applications for optimizing performance.

While these results are promising, the study’s limitations, including the relatively small sample size and lack of blinding, should be addressed in future research. Larger-scale, randomized controlled trials with standardized cryostimulation protocols are needed to confirm the observed effects and further explore the underlying mechanisms. Additionally, investigating the long-term impact of PBC across diverse sports disciplines and training stages could provide valuable insights into its broader applications in athletic performance and recovery.

In conclusion, this study supports the inclusion of PBC as a practical and effective recovery and performance-enhancing tool for soccer players, with the potential to contribute to better training outcomes and competition readiness.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; methodology, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; software, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; validation, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A..; formal analysis, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; investigation, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; resources, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; data curation, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; writing—review and editing, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; visualization, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; supervision, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; project administration, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A.; funding acquisition, I.R., J.O.K. and B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Study was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Karol Marcinkowski University of Medical Sciences in Poznań (Resolution No. 845/22) and entered in the Clinical Trials Register (ANZCTR of Australia and New Zealand, ACTRN; reference number 12622001541796). Football players voluntarily participated in the study and were informed about the study protocol, the risks of testing and research, and their rights in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves).

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kilduff, L.P.; Finn, C.V.; Baker, J.S.; Cook, C.J.; West, D.J. Preconditioning strategies to enhance physical performance on the day of competition. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2013, 8, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangsbo, J. Football physiology-with particular emphasis on intense intermittent exercises. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. Supplementum 1994, 619, 1–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, P.S.; Sheldon, W.; Wooster, B.; Olsen, P.; Boanas, P.; Krustrup, P. High-intensity running in English FA Premier League soccer matches. Journal of Sports Sciences 2009, 27, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankiewicz, B.; Środa, J. Optimization of sports training in football on the example of players of the 4th league team “Grom Osie”. Journal of Education, Health and Sport 2016, 6, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, J.J.; Hodges, D.; Roberts, C.; Sinclair, J.K.; Page, R.M.; Allan, R. Effect of alterations in whole-body cryotherapy (WBC) exposure on post-match recovery markers in elite Premier League soccer players. Biol Sport. 2022, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lombardi, G.; Ziemann, E.; Banfi, G. Whole-Body Cryotherapy in Athletes: From Therapy to Stimulation. An Updated Review of the Literature. Frontiers in Physiology 2017, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewski, P.; Bitner, A.; Słomko, J.; Szrajda, J.; Klawe, J.J.; Tafil-Klawe, M.; Newton, J.L. Whole-body cryostimulation increases parasympathetic outflow and decreases core body temperature. Journal of Thermal Biology 2014, 45, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiecień, S.Y.; McHugh, M.P. The cold truth: The role of cryotherapy in the treatment of injury and recovery from exercise. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2021, 121, 2125–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubkowska, A.; Bryczkowska, I. The influence of cryogenic temperatures used in cryostimulation and systemic cryotherapy treatments on selected components of the antioxidant capacity of the body. W H. Pobielska & A. Skrzek (red.), Application of Low Temperatures in Biomedicine. Oficyna Wydawnictwa Politechniki Wrocławskiej. 2012. 125–133.

- Rose, C.; Edwards, K.M.; Siegler, J.; Graham, K.; Caillaud, C. Whole-body cryotherapy as a recovery technique after exercise: A review of the literature. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2017, 38, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, A.; Ribbans, W.J.; Hohenauer, E.; Baross, A.W. The effect of repetitive whole-body cryotherapy treatment on adaptations to a strength and endurance training programme in physically active males. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2022, 4, 834386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, A.; Bottaro, M.; Ferreira-Junior, J.B.; Vieira, C.; Cleto, V.A.; Cadore, E.L.; Simões, H.G.; Carmo, J.D.; Brown, L.E. Does whole-body cryotherapy improve vertical jump recovery following a high-intensity exercise bout? Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine 2015, 6, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihailovic, T.; Groslambert, A.; Bouzigon, R.; Feaud, S.; Millet, G.P.; Gimenez, P. Acute responses to repeated-sprint training in hypoxia combined with whole-body cryotherapy: A preliminary study. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2014, 19, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dybek, T.; Szyguła, R.; Klimek, A.; Tubek, S. Impact of 10 sessions of whole body cryostimulation on aerobic and anaerobic capacity and on selected blood count parameters. Biology of Sport 2012, 29, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, J.; Micielska, K.; Kozłowska, M.; Wnorowski, K.; Skrobecki, J.; Radzimiński, L.; Babińska, A.; Rodziewicz, E.; Lombardi, G.; Ziemann, E. A 2-week specific volleyball training supported by the whole-body cryostimulation protocol induced an increase of growth factors and counteracted deterioration of physical performance. Frontiers in Physiology 2018, 9, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, E.M.; Cooke, J.; McKune, A.J.; Pyne, D.B. Application of acute pre-exercise partial-body cryotherapy promotes jump performance, salivary α-amylase, and athlete readiness. Biology of Sport 2022, 39, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savic, M.; Fonda, B.; Sarabon, N. Actual temperature during and thermal response after whole-body cryotherapy in cryocabins. Journal of Thermal Biology 2013, 38, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).