1. Introduction

The critical properties of a system undergoing a second-order phase transition is strongly dependent on the dimension of the underlying lattice. In fact, the lattice dimension is one of the crucial factors to determine the universality class of a particular second-order phase transition (the other factors consist of the dimension of the order parameter and symmetry and range of the particle interactions). The renormalization group theory turned out to be a successful framework to understand the universal aspects of the critical phenomena from the knowledge of the basic microscopic interactions (see, for instance, Ref. [

1] and references therein).

It is also well established in the literature that each system has its proper lower critical dimension

, below which there is no phase transition, and also an upper critical dimension

, above which the transition is governed by the mean-field exponents [

2]. Of course, the upper critical dimension has only a theoretical interest, because

is usually above the three-dimensional space of the physical sample realizations [

3]. Just to cite some examples, we have

and

for the Ising model [

1],

and

for the isotropic Heisenberg model [

1],

[

4] and

[

5] for the Ising spin-glass system. More recently, it has been reported that

and

for the majority vote model on regular lattices [

6].

The magnetic models cited above, defined on regular Bravais lattices, are well studied in the literature because they are in some sense easier to define, suitable to being simulated using different sort of computer algorithms, and with plenty physical realizations to be compared to. Nevertheless, magnetic models can as well be defined on scaling free lattices, like networks and specific graphs. In this case, however, it is not possible to assert, a priori, whether the system will or will not have a phase transition. Moreover, when a phase transition is present, one has to carefully investigate whether the transition is of first or second order. Some magnetic systems, like Ising, Potts and Blume-Capel models, have already been studied on some complex lattices comprising Appolonian, Barabási-Albert, Voronoi-Delauny and small-world networks [

7].

There are also different sort of dynamical systems, not along the line of the magnetic ones, that are studied on regular lattices. In this case, the determination of the lower and upper dimensions turns to be a point of theoretical interest. For instance, an interesting result has been obtained for the majority vote model [

8] through Monte Carlo simulations in several

D-dimensional lattices [

6]. It has been reported that the model do present an upper critical dimension

, despite for

the majority vote model being in the same universality class as the Ising model (recall that

of the Ising class).

In this work, we will address to the question of the upper critical dimension of the Biswas-Chatterjee-Sen (BChS) model, in its discrete version, and defined on Solomon networks (SNs). The BChS model is a complex system that takes into account the dynamics of opinions of its individual constituents [

9,

10,

11]. Intrinsic in the system is the fact that the individuals in a community can not only influence their neighbors but be influenced by them as well. Accordingly, the individual opinion variables evolve according to pair interactions that are allowed to be positive or negative. The interaction signs are then modeled by a single noise probability

q that represents the fraction of negative interactions. This noise probability plays a crucial role in the dynamics of this system. In fact,

q is the temperature equivalent in magnetic models.

On regular lattices, and also in some special networks, the BChS model has a second-order phase transition at a critical value

, with critical exponents different from the usual magnetic models and dependent on the particular chosen lattice [

12]. For a recent review on the progress already made in this model see Ref. [

13].

With respect to scaling free lattices, in the direction of treating opinion dynamics, a more realistic environment has been proposed by Sorin Solomon [

14,

15], who considers two different lattices. One lattice reflects one kind of environment, for instance the home place, and the other lattice a different situation, for instance the workplace. In practice, labeling

i the sites in the workplace lattice, a random permutation

of the order already established in this lattice provides the sites in the home place lattice. The actuality in this process resides in the fact that the neighbors at home differ from the neighbors at the workplace. Thus, like in the King Solomon biblical story, in such construction each individual is equally shared by two lattices. So, the net interaction of the relevant variables defined at site

i turns out to be a sum of the corresponding interactions of the site

i with its neighboring sites on the workplace lattice, plus the interactions with the neighbor sites of

on the home place lattice. It should be stressed that the increase in the connectivity of each site

i makes the SNs close to small-world networks [

16,

17].

The BChS model has been previously studied in

,

, and

SNs [

12,

18,

19]. The critical exponents of the second-order phase transition depend on the dimension of the lattices

D, as expected from general renormalization group arguments. Since the majority vote model present an upper critical dimension, it would be worthwhile to see whether the BChS model in higher dimension SNs will have critical exponents in the direction of the mean-field ones.

Thus, in the present work, the BChS dynamical system on SNs has been studied through extensive Monte Carlo simulations by considering lattices in

dimensions. In the next section we have: the definition of the BChS model in the discrete opinion dynamics; the themodynamic-like variables that are used in describing the phase transition; and the corresponding finite-size-scaling relations together with some details of the Monte Carlo simulations. The results are discussed in

Section 3 and some concluding remarks are summarized in the last section.

3. Results and Discussion

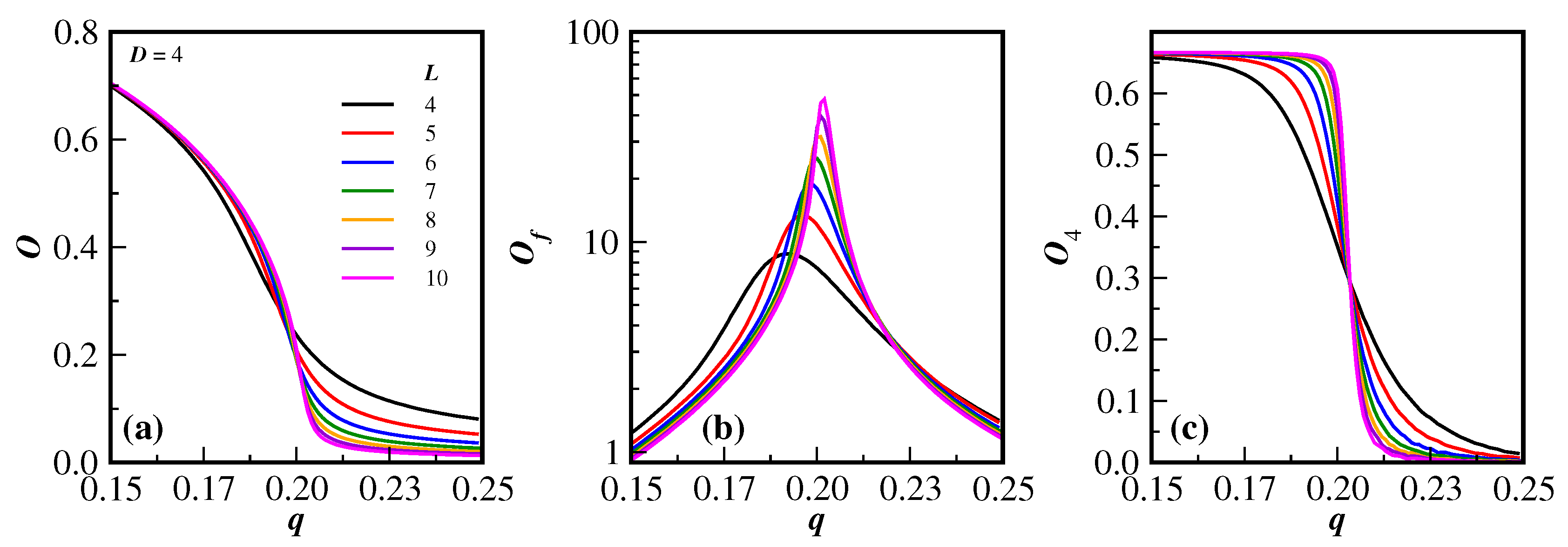

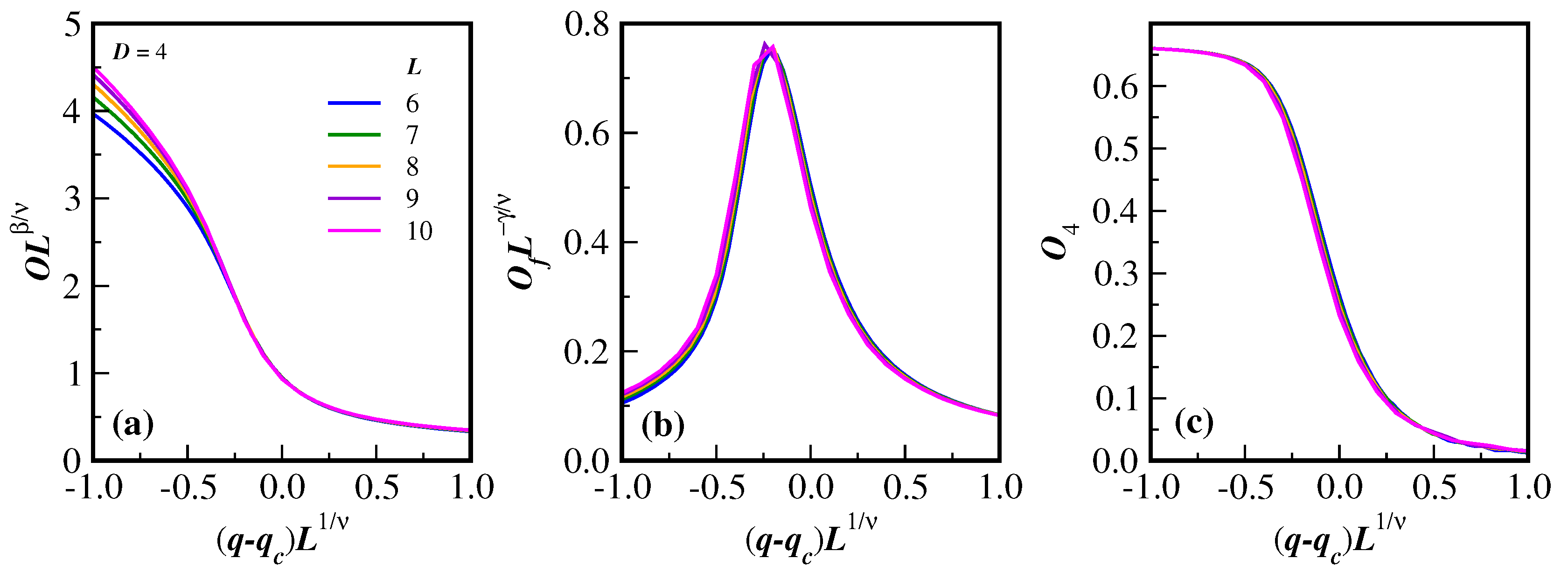

As a matter of example, the general behavior of the relevant quantities for this model in

namely

O,

and

, given by Eqs. (

6)-(8), are respectively displayed in the three panels (a), (b) and (c) of

Figure 1. The different lattice sizes are listed in the legend of

Figure 1(a). In all these panels, only the lines of the data are shown for a clearer visualization of the dependence of the respective quantities as a function of the noise probability

q. From the behavior of

O,

and

close to the transition region, it is clear that the system undergoes a phase transition, since the derivatives of

O and

with respect to

q increase in magnitude as the lattice size increases, so does the peak of

(note that, for a better view of the peaks, the vertical axis of

Figure 1(b) gives

in a logarithm scale). In addition, the fourth order Binder cumulants

cross at the same region, which is equivalent to the critical noise transition. Similar patterns, as highlighted in this figure, have been previously obtained for

and are also obtained for

and 6. However, as it will be seen below, the cumulant crossing for higher dimensions

are not so well defined as for the case

. Some details of extracting the critical properties of the model from these kind of data are discussed below.

Let us first consider the fourth-order Binder cumulant of the order parameter

, as a function of the disorder parameter

q, which is depicted in the left panels of

Figure 2 for several lattice sizes

L and dimension

D. In panels

Figure 2(a),

Figure 2(c) and

Figure 2(e), we have

,

and

, respectively. One can clearly see from panel

Figure 2(a) for

that the system undergoes a second-order phase transition, since the cumulants tend to cross at the same value

q, which corresponds to the critical disorder parameter

[

21]. In the axes scales used in

Figure 2(a) one can make a rough estimate of the critical noise and the universal value of the Binder cumulant

and

, respectively. It can also be noticed that from

Figure 2(c) and

Figure 2(e) (

,

we do not have a clear estimate either of

or

. This is a result of the smaller lattices that have been used because the number of sites to be simulated exponentially increases with

D. Nevertheless, from the inset of the left panels it is seen that the slope of

systematically increases with the lattice size. From the maximum value of the slope of

with respect to

q one is able to obtain the correlation length exponent

. The magnitude of the derivative

has been numerically computed from the original simulated data. The ln-ln plot of this derivative, as function of the lattice size

L, is illustrated in the main graphs of the right panels of

Figure 2 for each considered dimension

D. The slope of the linear fit of the data, according to Eq. (12), corresponds to the exponent ratio

. The values of

are given in the proper figures. In dimensions

and

the smaller lattices have not been taken in the linear fit.

The position

of the peak of the derivative

can also be used to estimate the critical value

in the thermodynamic limit. The behavior of

as a function of

is shown in the inset of

Figure 2(b),

Figure 2(d) and

Figure 2(f). It is quite apparent the non linearity of the data due to the finite-size effects, mainly for

. Thus, rather than using Eq. (13), the data should be fitted by resorting to finite-size-scaling corrections. In this case, usual power law corrections, which are quite common in several models, do not produce a reasonable fit to the

. Instead, the data could be well fitted with logarithm corrections of the form

where

is the critical noise of the infinite system and

and

are non-universal constants. The corresponding critical noise are given in the insets for each value of the lattice dimension

D. The value of the critical noise probability seems not to change with the lattice dimension, whereas the exponents do significantly change with

D.

Although for

and

the value of extrapolated

is not clearly seen in the cumulants crossings, for

the exrapolated

value is, within the error bars, comparable to crossings in

Figure 2(a), namely

. Even a linear fit to data in the inset of

Figure 2(b) gives a comparable value

. However, good estimates of the universal value

are still quite unprecise from

Figure 2(c) and (e). This means that for the lattice sizes used in the present model, finite-size-effects turn out to become actually important for dimensions

.

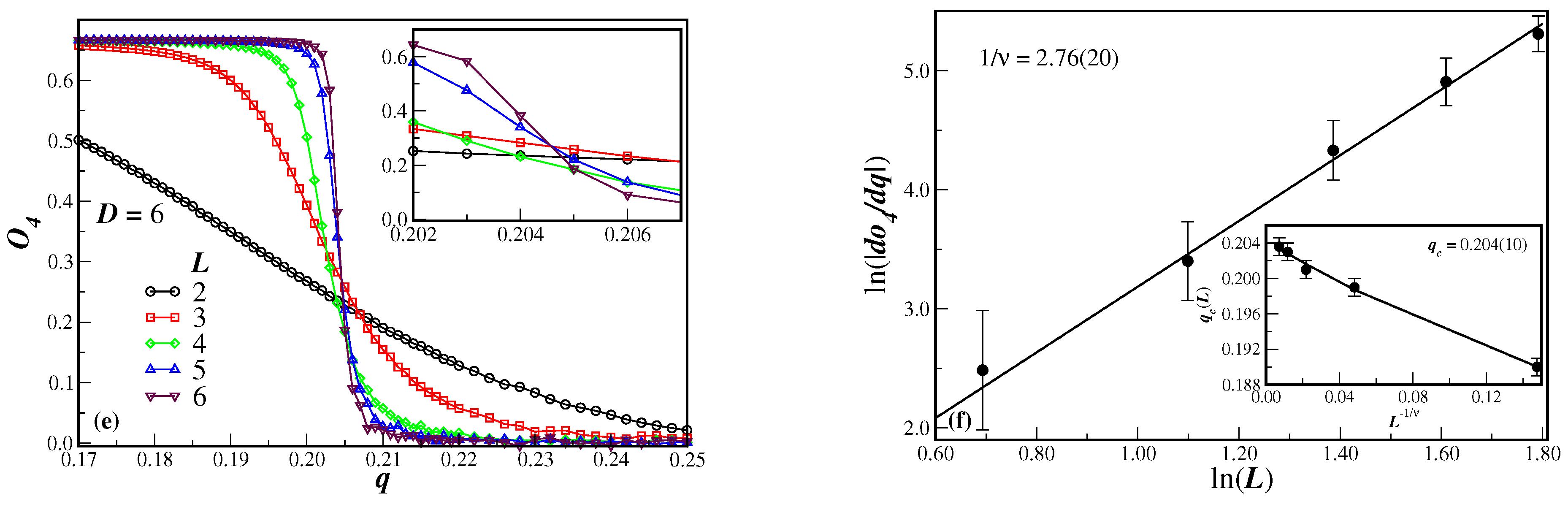

The estimate of the critical noise probability

allows us now, through Eqs. (

9) and (10), to evaluate the critical exponent ratio

and

by just computing the order parameter

and its fluctuation

at

for different lattice sizes

L and spatial dimensions

D. In the case of

, we also have its maximum value

at the noise probability

.

Figure 3 depicts the ln-ln plot of these quantities as a function of the system size

L. The corresponding slopes of the linear fit give the respective critical exponent ratios and are written in the legends of

Figure 3(a), (b) and (c) for

,

and

, respectively. Although

and

have different values for each lattice size, the

exponent estimate agree well within the error bars.

The noise probability

, at which the fluctuation variable

exhibits a maximum, can be interpreted as another

. Accordingly, new estimates of the critical value

can be done using Eq. (

14).

Figure 4 displays the values of

so obtained as a function of

for the different lattice dimension

D. As in the inset of the panels in

Figure 2, the non-alignment of the data is apparent, and needs the consideration of finite-size-scaling corrections to estimate the critical noise probability. The full line in

Figure 4 give indeed the best fit according to Eq. (

14). The results of

for each dimension is given in the legend of the figure. The error in

has been adopted as

, the interval used to increase the noise probability in the simulations.

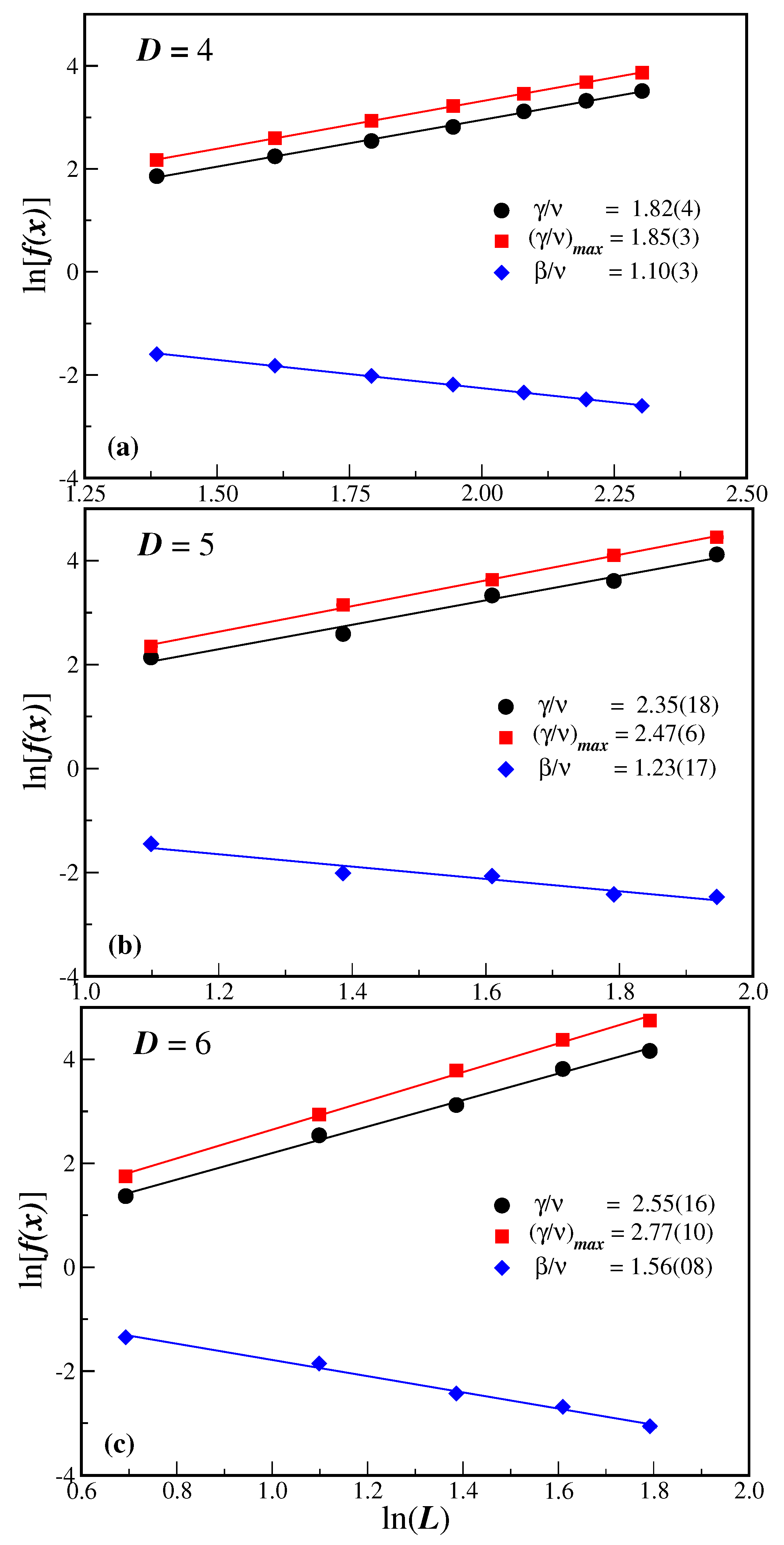

Finally,

Figure 5 also shows, in

dimension, the data collapse obtained for the rescaled order parameter

in panel (a), for the rescaled fluctuation of the order parameter

in panel (b), and for the rescaled reduced Binder cumulant

in panel (c). All quantities are given as a function of the rescaled probability displacement

. As in the panels of

Figure 1, just the lines of the actual Monte Carlo data have been plotted for a better evaluation of the collapse and the accuracy of the critical quantities. The corresponding lattice sizes

L are listed in the legend of

Figure 5(a), where the two smaller lattice sizes have been omitted in the data collapse. Apart from the order parameter for small values of the noise probability, it is apparent the excellent agreement with the scaling relations given in Eqs. (

9), (10), and (13). This is a clear indication that the evaluation of the critical exponents ratio

,

, and

are reasonably accurate.

Despite the finite-size effects being more pronounced as the lattice dimension increases, similar results, as those illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 5, are also obtained for higher dimensions

D using the corresponding critical values of the noise probability and exponent ratios.

4. Concluding Remarks

The discrete version of the Biswas-Chatterjee-Sen model, defined on , 5- and 6-dimensional Solomon networks, has been studied through extensive Monte Carlo simulations as a function of the local consensus controlling probability. From the computer simulation data and from the scaling behavior of the used thermodynamical-like quantities, it has been seen that the model really undergoes a well defined second-order phase transition for all treated dimensions.

Table 1 summarizes the numerical results of the criticality observed for the present values of lattice dimension

D namely

, 5, and 6, together with the results previously obtained for

, 2 and 3 from Refs. [

18,

19]. An inspection of this table readily says: (

i) the critical noise probability seems not to strongly depend on the lattice dimension, as is usual in spin systems, where in the latter case the increase of the number of nearest-neighbors effectively increases the transition temperature; (

ii) the critical exponents, on the other hand, do depend on the lattice dimension, as is expected from universality arguments. In this case, the exponent ratios systematically increase as

D increases; (

iii) the hyperscaling relation

is, within the error bars, not violated and it is actually satisfied in all of the studied dimensions. The same holds for the equivalent relation

using the correlation length exponent, although in the latter case one observes a larger error; (

iv) the lower critical dimension for this model is 0, but from the present simulations there is no indication of an upper critical dimensional from where the mean-field exponents are valid. We can note from

Table 1 that the closest mean-field exponents one obtains is for dimension

.

As a result, contrary to the majority vote model [

6], the BChS model on SNs seems not to present an upper critical dimension. In addition, the model has logarithm finite-size corrections, as evidenced in the behavior of critical noise probability as a function of the lattice size.

The crossings of the cumulants, which in general give further estimates of

, could not be considered in this dynamical system for

, although for

it was possible to obtain good estimates of

and

from them [

12] (also using logarithm-like corrections). In the present dimensions, even and odd lattice sizes follow different uniform trends to reach the thermodynamic limit value. However, since larger lattices could not be simulated, estimates for the critical quantities turned out to be very poor due to few data available for the proper fits.

As a final remark, it can be noticed that for

the exponent ratios

and

are, within the error bars, almost identical to each other. This is in agreement of what happens for equilibrium Ising-like models [

22]. However, such equality does not happen for BChS model on directed Barabási-Albert Networks [

25].