Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Edible insects constitute a healthy food source with high nutritional value, promoted in coordinated efforts to address global food insecurity by providing a sustainable alternative to tradi-tional animal protein. The present study sought to explore consumers’ perceptions and attitudes to-ward insect consumption, and also define the main motivational factors influencing public awareness and acceptance toward entomophagy. Methods: Using a qualitative research design, individual-level data were selected from a sample of 70 consumers in Greece via semi-structured personal in-depth interviews. The Grounded Theory frame-work was adopted to develop awareness, perception and acceptance drivers. Results: Although a small proportion of participants completely ignored the usage of insects as food and food ingredients, the great majority demonstrated abhorrence toward entomophagy, describing feelings of disgust and repulsion. Furthermore, respondents seemed to be reluctant towards the inclusion of edible insects and insect-based food options available to consumer markets through the food pro-cessing businesses and food distribution channels. Food safety concerns were strong since many con-sumers seemed to question the regulations in insect cultivation and the preparation of insect-based foods. Conclusions: Lack of information and cultural influences were found to restrict consumers’ acceptance of entomophagy, whereas health and food safety concerns comprised an inhibiting factor in incorporating edible insects and insect components in the Greek cuisine. This study emphasized the need for a holis-tic information plan, which will help both food businesses and consumers understand the vital role of edible insects in modern food environments.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

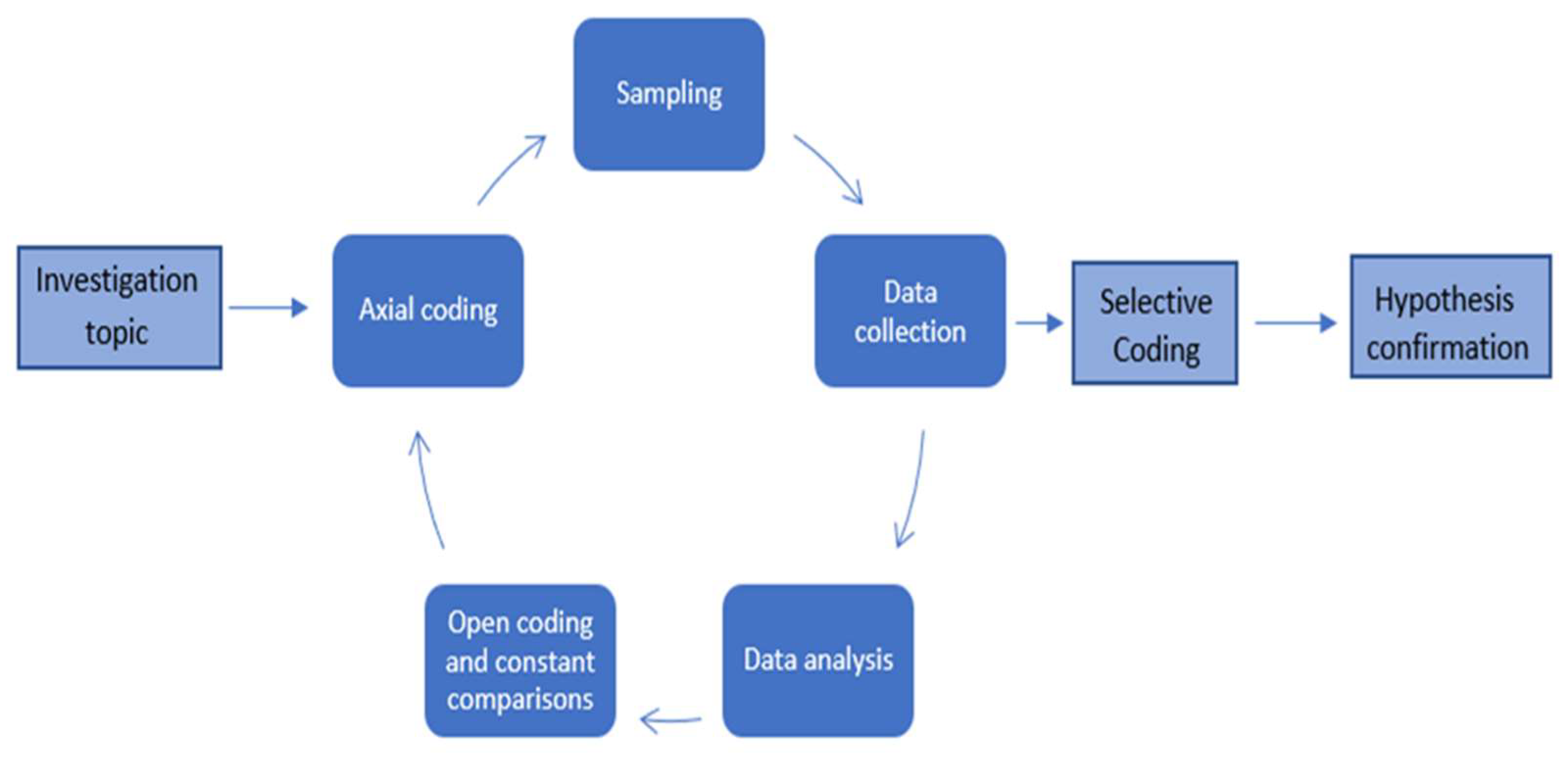

2.1. Theoretical framework of the study

2.2. Sample selection

2.3. Data collection and analysis

- “Have you ever heard of the term entomophagy?”

- “Are you aware of the benefits of eating edible insects?”

- “Have you ever eaten edible insects before?”

- “If yes, in what form (raw, cooked, grounded, or incorporated in food)?”

- “What are your feelings towards entomophagy?”

- “What are the images and thoughts that come to your mind when thinking of edible insects?”

- “Are you willing to try edible insects?”

- “Are you willing to try food that has edible insects incorporated into it?”

- “What are your reasons to try edible insects?”

- “How do you find the idea of having edible insects sold in grocery stores and having them incorporated into the menu of restaurants in the future in Greece?”

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ profile

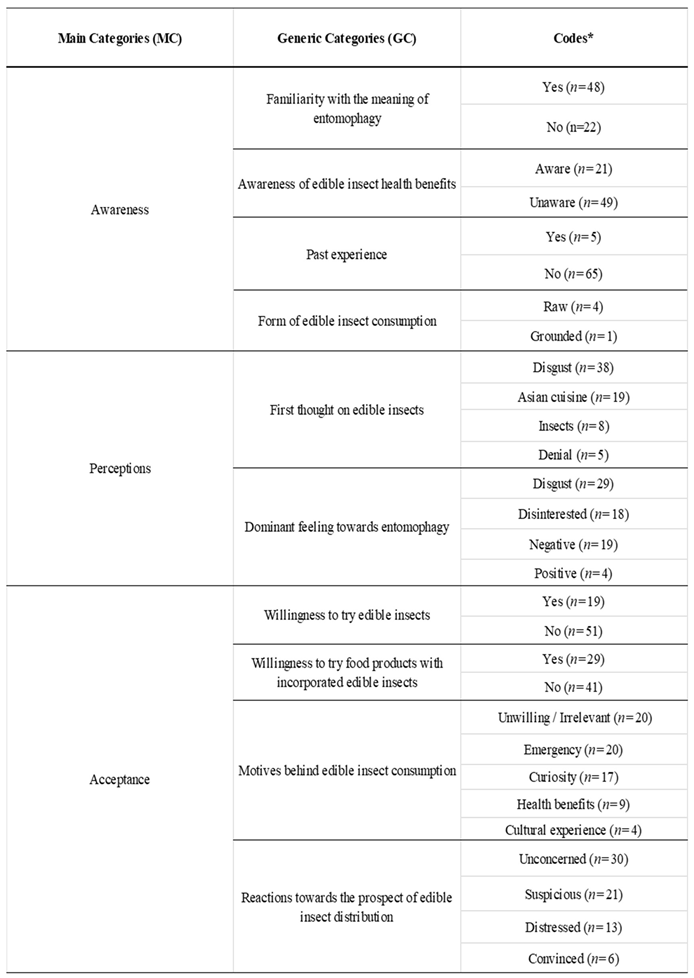

3.2. Grounded theory results

- Consumers’ awareness of entomophagy (MC1),

- Consumers' perceptions of entomophagy (MC2),

- Consumers' acceptance of edible insects (MC3).

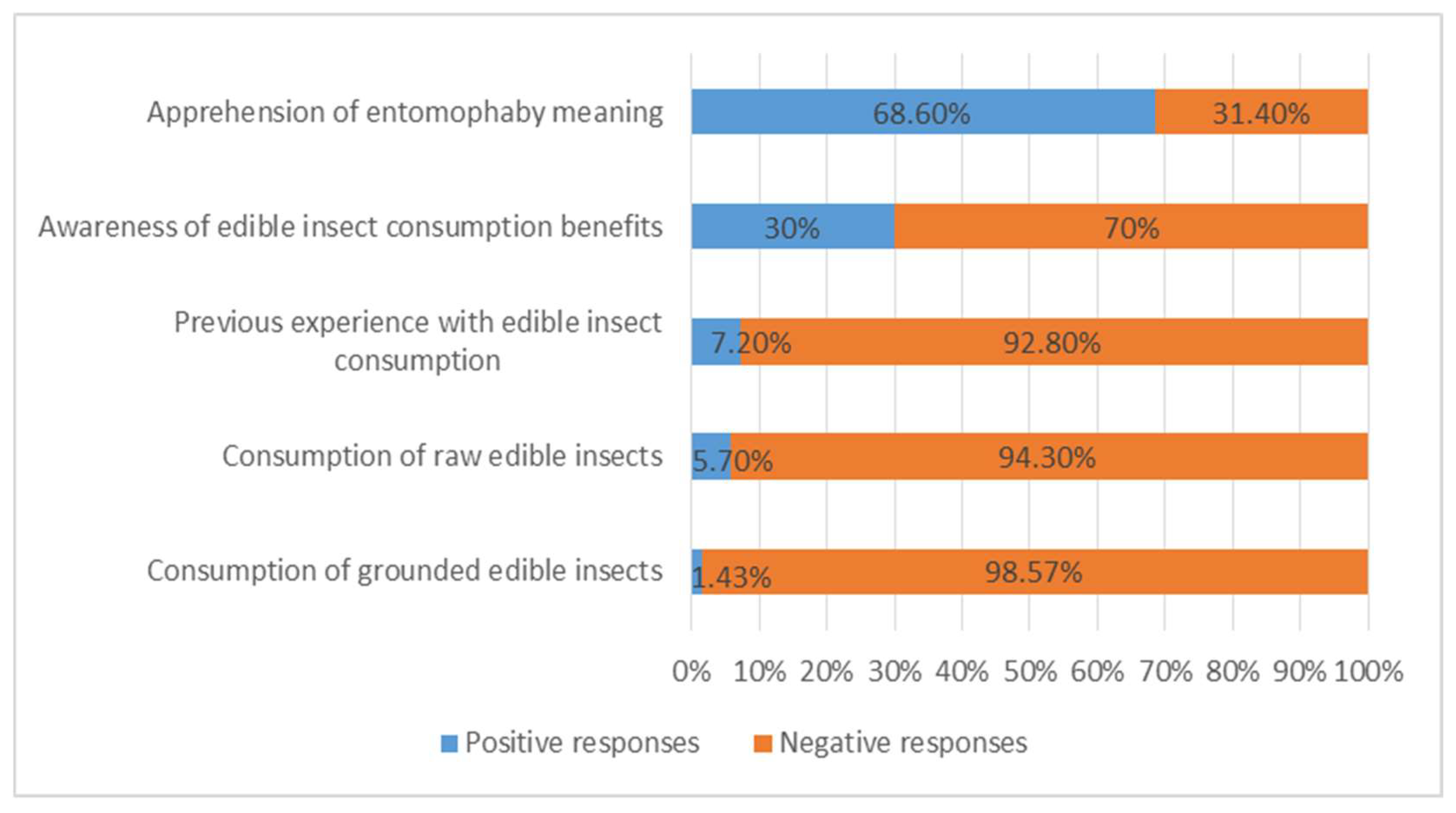

3.2.1. Participants’ awareness of entomophagy

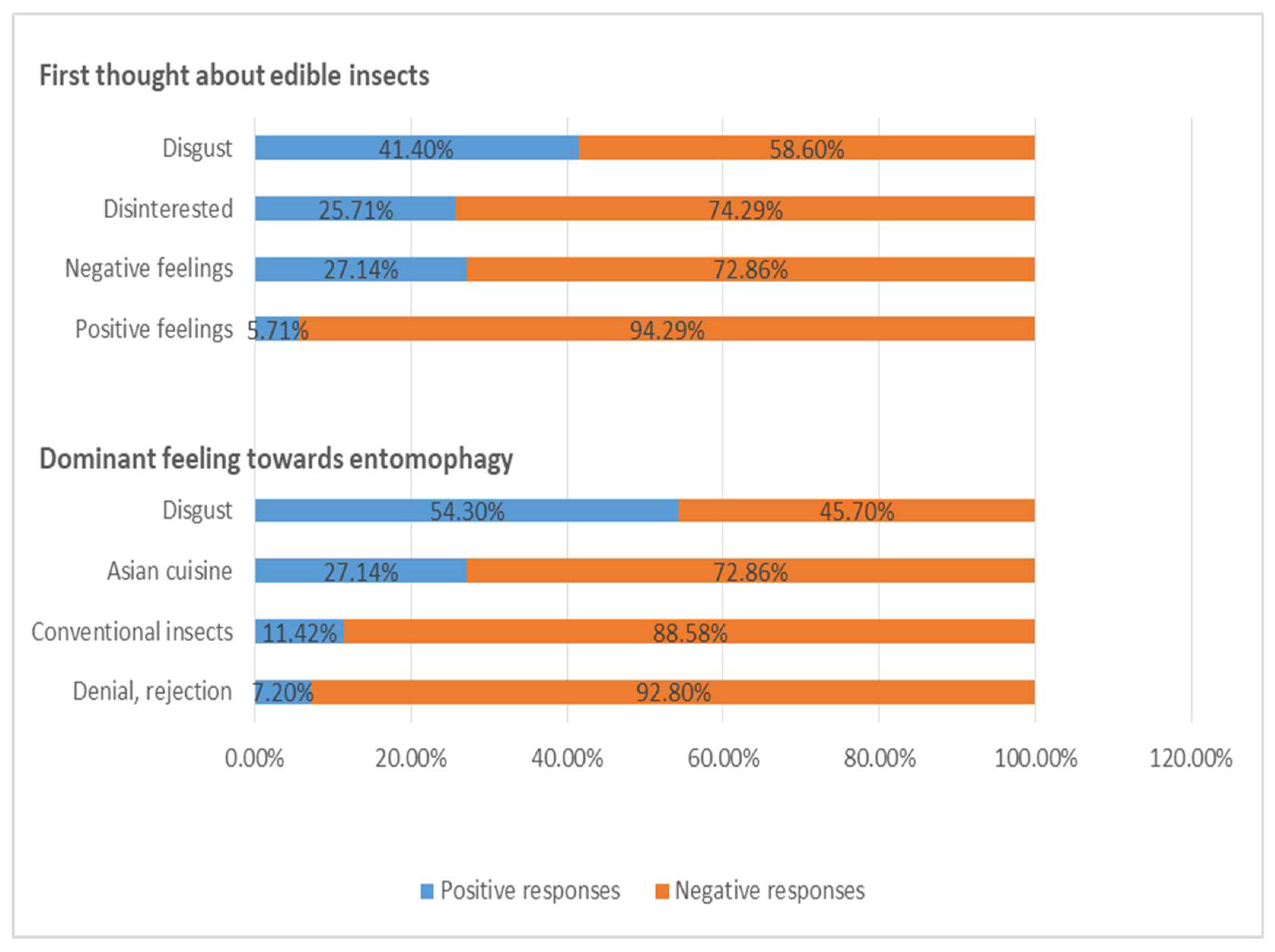

3.2.2. Participants’ perceptions of entomophagy

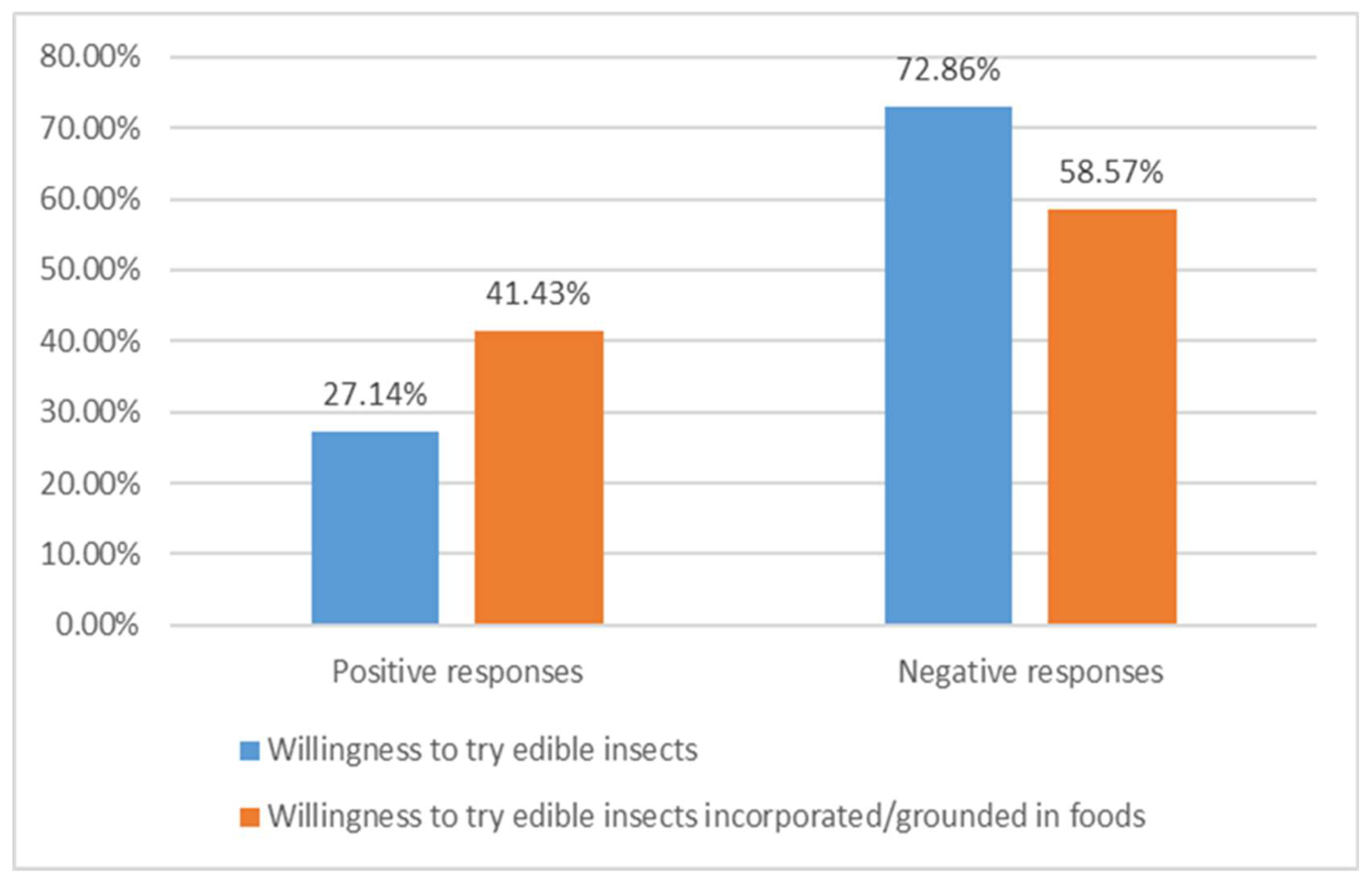

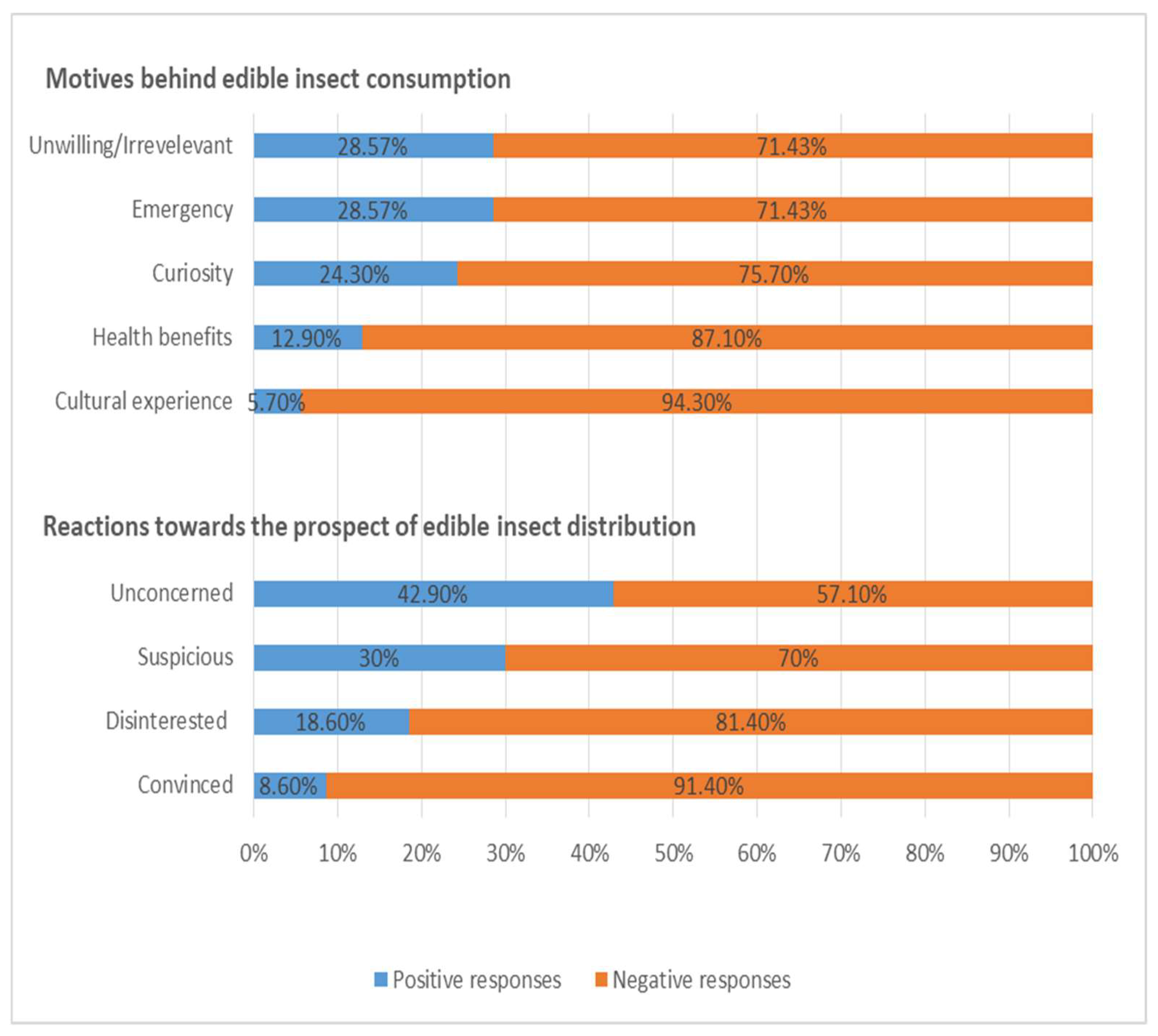

3.2.3. Participants’ acceptance of entomophagy

4. Discussion

4.1. Participants’ awareness of entomophagy

4.2. Participants’ perceptions of entomophagy

4.3. Participants’ acceptance of entomophagy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A Thematic categories developed from data abstraction (N=70)

References

- Verneau, F., Amato, M., & Barbera, F. L. (2021). Edible insects and global food security. Insects 12: 472. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A., Kumar, A., & Biswas, G. (2024). Exponential population growth and global food security: challenges and) alternatives. In Bioremediation of Emerging Contaminants from Soils (pp. 1-20). Elsevier.

- Falcon, W. P., Naylor, R. L., & Shankar, N. D. (2022). Rethinking global food demand for 2050. Population and Development Review, 48(4), 921-957. [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Martínez, A. C., Parra-Cota, F. I., & de Los Santos-Villalobos, S. (2022). Beneficial Microorganisms in sustainable agriculture: harnessing microbes’ potential to help feed the world. Plants, 11(3), 372. [CrossRef]

- Dinar, A., Tieu, A., & Huynh, H. (2019). Water scarcity impacts on global food production. Global Food Security, 23, 212-226. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Huang, J., Prell, C., & Bryan, B. A. (2021). Changes in supply and demand mediate the effects of land-use change on freshwater ecosystem services flows. Science of the Total Environment, 763, 143012. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F., & Steinberger, J. K. (2018). A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature sustainability, 1(2), 88-95. [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R. P., Correia, P., Coelho, C., & Costa, C. A. (2021). The role of edible insects to mitigate challenges for sustainability. Open Agriculture, 6(1), 24-36. [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Encinas, L. A., Santoyo, G., Peña-Cabriales, J. J., Castro-Espinoza, L., Parra-Cota, F. I., & Santos-Villalobos, S. D. L. (2021). Transcriptional regulation of metabolic and cellular processes in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the face of temperature increasing. Plants, 10(12), 2792.

- Connolly, S., O'Flaherty, V., & Krol, D. J. (2023). Inhibition of methane production in cattle slurry using an oxygen-based amendment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 394, 136272. [CrossRef]

- Maracchi, G. (2012). Cambiamenti climatici e agricoltura del futuro: una rivoluzione smart. Georgofili: atti dell'Accademia dei Georgofili: Serie VIII, Vol. 9, Tomo I, 2012, 34-49.

- Palmieri, N., Perito, M. A., Macrì, M. C., & Lupi, C. (2019). Exploring consumers’ willingness to eat insects in Italy. British Food Journal, 121(11), 2937-2950. [CrossRef]

- Aravind, L., & Devegowda, S. (2019). Alternative food production and consumption: Evolving and exploring alternative protein supplement potential through Entomoceuticals. Int. J. Chem. Stud, 7, 1393-1397.

- Palmieri, N., & Forleo, M. B. (2020). The potential of edible seaweed within the western diet. A segmentation of Italian consumers. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 20, 100202. [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A. (2020). Insects as food and feed, a new emerging agricultural sector: a review. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 6(1), 27-44. [CrossRef]

- Imathiu, S. (2020). Benefits and food safety concerns associated with consumption of edible insects. NFS journal, 18, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Halonen, V., Uusitalo, V., Levänen, J., Sillman, J., Leppäkoski, L., & Claudelin, A. (2022). Recognizing potential pathways to increasing the consumption of edible insects from the perspective of consumer acceptance: Case study from finland. Sustainability, 14(3), 1439. [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A., & Oonincx, D. G. (2017). The environmental sustainability of insects as food and feed. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 37, 1-14.

- Lange, K. W., & Nakamura, Y. (2021). Edible insects as future food: chances and challenges. Journal of future foods, 1(1), 38-46. [CrossRef]

- Borges, M. M., da Costa, D. V., Trombete, F. M., & Câmara, A. K. F. I. (2022). Edible insects as a sustainable alternative to food products: An insight into quality aspects of reformulated bakery and meat products. Current Opinion in Food Science, 46, 100864. [CrossRef]

- Bava, L., Jucker, C., Gislon, G., Lupi, D., Savoldelli, S., Zucali, M., & Colombini, S. (2019). Rearing of Hermetia illucens on different organic by-products: Influence on growth, waste reduction, and environmental impact. Animals, 9(6), 289.

- Guiné, R. P., Florença, S. G., Costa, C. A., Correia, P. M., Ferreira, M., Cardoso, A. P., ... & Damarli, E. (2022). Investigation of the level of knowledge in different countries about edible insects: cluster segmentation. Sustainability, 15(1), 450. [CrossRef]

- da Silva Lucas, A. J., de Oliveira, L. M., Da Rocha, M., & Prentice, C. (2020). Edible insects: An alternative of nutritional, functional and bioactive compounds. Food chemistry, 311, 126022.

- Nowakowski, A. C., Miller, A. C., Miller, M. E., Xiao, H., & Wu, X. (2022). Potential health benefits of edible insects. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 62(13), 3499-3508.

- Xiaoming, C., Ying, F., Hong, Z. and Zhiyong, C. (2010) Review of the nutritive value of edible insects. FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok, Thailand „Forest insects as food: humans bite back” (Chiang Mai, Thailand, 19-21 February 2008). In Proceedings of a workshop on Asia-Pacific resources and their potential for development. Chiang Mai (93-98).

- Oonincx, D. G. A. B., & Finke, M. D. (2021). Nutritional value of insects and ways to manipulate their composition. Journal of insects as food and feed, 7(5), 639-659. [CrossRef]

- Gamboni, M., Carimi, F., & Migliorini, P. (2012). Mediterranean diet: an integrated view. SUSTAINABLE DIETS AND BIODIVERSITY.

- Grdeń, A.S.; Sołowiej, B.G. Macronutrients, Amino and Fatty Acid Composition, Elements, and Toxins in High-Protein Powders of Crickets, Arthrospira, Single Cell Protein, Potato, and Rice as Potential Ingredients in Fermented Food Products. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12831. [CrossRef]

- Murefu, T. R., Macheka, L., Musundire, R., & Manditsera, F. A. (2019). Safety of wild harvested and reared edible insects: A review. Food Control, 101, 209-224. [CrossRef]

- Orsi, L., Voege, L. L., & Stranieri, S. (2019). Eating edible insects as sustainable food? Exploring the determinants of consumer acceptance in Germany. Food Research International, 125, 108573. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R., Kallas, Z., Haddarah, A., El Omar, F., & Pujolà, M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on willingness to consume insect-based food products in Catalonia. Foods, 10(4), 805. [CrossRef]

- Dossey, A.T.; Morales-ramos, J.A.; Rojas, M.G. Insects as Sustainable Food Ingredients. Production, Processing, and Food Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; ISBN 9780128028568.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Gkrintzali, G., Georgiev, M., Matas, R. G., Maggiore, A., Giarnecchia, R., ... & Bottex, B. (2024). EFSA's activities on emerging risks in 2022 (Vol. 21, No. 9, p. 8995E).

- Raubenheimer, D.; Rothman, J.M. Nutritional ecology of entomophagy in humans and other primates. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 141–160. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta (2009). "Anthropo-Entomophagy: Cultures, Evolution And Sustainability". Entomological Research. 39 (5): 271–288. [CrossRef]

- Dalby, A., & Grainger, S. (1996). The classical cookbook. Getty Publications.2002; ISBN 978-0-89236-394-0.

- Olivadese, M., & Dindo, M. L. (2023). Edible insects: a historical and cultural perspective on entomophagy with a focus on Western societies. Insects, 14(8), 690. [CrossRef]

- Mavrofridis, G., Petanidou, T. (2022) Bee brood as traditional human food on Andros Island, Greece, Journal of Apicultural Research. [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. The food neophobia scale and young adults’ intention to eat insect products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 68–76. [CrossRef]

- Lorini, C., Ricotta, L., Vettori, V., Del Riccio, M., Biamonte, M. A., & Bonaccorsi, G. (2021). Insights into the predictors of attitude toward entomophagy: The potential role of health literacy: A cross-sectional study conducted in a sample of students of the University of Florence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5306. [CrossRef]

- Modlinska K, Adamczyk D, Goncikowska K, Maison D, Pisula W: The effect of labelling and visual properties on the acceptance of foods containing insects. Nutrients 2020, 12:E2498.

- Florença, S.G.; Guiné, R.P.F.; Gonçalves, F.J.A.; Barroca, M.J.; Ferreira, M.; Costa, C.A.; Correia, P.M.R.; Cardoso, A.P.; Campos, S.; Anjos, O.; et al. The Motivations for Consumption of Edible Insects: A Systematic Review. Foods 2022, 11, 3643. [CrossRef]

- Kamenidou IE, Mamalis S, Gkitsas S, Mylona I, Stavrianea A. Is Generation Z Ready to Engage in Entomophagy? A Segmentation Analysis Study. Nutrients. 2023 Jan 19;15(3):525. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gkinali, A. -A., Matsakidou, A., Michailidis, A., & Paraskevopoulou, A. (2024). How Do Greeks Feel about Eating Insects? A Study of Consumer Perceptions and Preferences. Foods, 13(19), 3199. [CrossRef]

- Bisconsin-Júnior, A., Rodrigues, H., Behrens, J. H., da Silva, M. A. A. P., & Mariutti, L. R. B. (2022). “Food made with edible insects”: Exploring the social representation of entomophagy where it is unfamiliar. Appetite, 173, 106001. [CrossRef]

- La Barbera, F., Verneau, F., Amato, M., & Grunert, K. (2018). Understanding Westerners’ disgust for the eating of insects: The role of food neophobia and implicit associations. Food quality and preference, 64, 120-125.

- Toti, E., Massaro, L., Kais, A., Aiello, P., Palmery, M., & Peluso, I. (2020). Entomophagy: A narrative review on nutritional value, safety, cultural acceptance and a focus on the role of food neophobia in Italy. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(2), 628-643.

- Videbæk, P. N., & Grunert, K. G. (2020). Disgusting or delicious? Examining attitudinal ambivalence towards entomophagy among Danish consumers. Food Quality and Preference, 83, 103913. [CrossRef]

- Van Thielen, L., Vermuyten, S., Storms, B., Rumpold, B., & Van Campenhout, L. (2019). Consumer acceptance of foods containing edible insects in Belgium two years after their introduction to the market. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 5(1), 35-44. [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I., Barrera Albores, E., & Hamm, U. (2019). The role of species for the acceptance of edible insects: Evidence from a consumer survey. British Food Journal, 121(9), 2190-2204. [CrossRef]

- Halonen, V. (2020). Exploring Finnish consumers' acceptance and potential to increase insect use as food. Masters thesis. LAHTI UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, LITHUANIA, https://lutpub.lut.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/161778/Diplomity%C3%B6_Halonen_Vilma.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed February 2025.

- Ranga, L., Vishnumurthy, P., & Dermiki, M. (2024). Willingness to consume insects among students in France and Ireland. Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research, 62(1), 108-129. [CrossRef]

- Moruzzo, R., Mancini, S., Boncinelli, F., & Riccioli, F. (2021). Exploring the acceptance of entomophagy: a survey of Italian consumers. Insects, 12(2), 123. [CrossRef]

- Tuccillo, F., Marino, M. G., & Torri, L. (2020). Italian consumers’ attitudes towards entomophagy: Influence of human factors and properties of insects and insect-based food. Food Research International, 137, 109619. [CrossRef]

- Orkusz, A., Wolańska, W., Harasym, J., Piwowar, A., & Kapelko, M. (2020). Consumers’ attitudes facing entomophagy: Polish case perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2427. [CrossRef]

- Gkitsas, S., Kamenidou, I., Mamalis, S., Mylona, I., Pavlidis, S., & Stavrianea, A. (2023, September). Generation Z Gender Differences in Barriers to Engage in Entomophagy: Implications for the Tourism Industry. In The International Conference on Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism (pp. 1-8). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Lim, W. M. 2024. What Is Qualitative Research? An Overview and Guidelines. Australasian Marketing Journal 1–31 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/14413582241264619.

- Taherdoost, H. (2022) What are Different Research Approaches? Comprehensive Review of Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method Research, Their Applications, Types, and Limitations. Journal of Management Science & Engineering Research 5, 53-63. [CrossRef]

- Tenny S, Brannan JM, Brannan GD. Qualitative Study. [Updated 2022 Sep 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470395/.

- Bazhan, M., Nastaran Keshavarz-Mohammadi, Hedayat Hosseini, Naser Kalantari. Consumers’ awareness and perceptions regarding functional dairy products in Iran: A qualitative research British Food Journal, Vol. 119 No. 2, 2017, pp. 253-266.

- Eldesouky A, Mesias FJ, Escribano M. Perception of Spanish consumers towards environmentally friendly labelling in food. Int J Consum Stud. 2020; 44: 64–76. [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Yu, H.; Ploeger, A. Exploring Influential Factors Including COVID-19 on Green Food Purchase Intentions and the Intention–Behaviour Gap: A Qualitative Study among Consumers in a Chinese Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7106. [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, P., Tamrakar, D., Shrestha, A., Shrestha, H., Karmacharya, S., Bhattarai, S., Bhandari, N., Malik, V., Mattei, J., Spiegelman, D., & Shrestha, A. (2022). Consumer acceptance and preference for brown rice—A mixed-method qualitative study from Nepal. Food Science & Nutrition, 10, 1864–1874. [CrossRef]

- Arviv, B., Amir Shani, Yaniv Poria. Delicious – but is it authentic: Consumer perceptions of ethnic food and ethnic restaurants. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2024, pp. 1934-1948. [CrossRef]

- de Morais Sato, P., Marcia Thereza Couto, Jonathan Wells, Marly Augusto Cardoso, Delanjathan Devakumar, Fernanda Baeza Scagliusi,Mothers' food choices and consumption of ultra-processed foods in the Brazilian Amazon: A grounded theory study, Appetite, Volume 148, 2020, 104602. [CrossRef]

- Huston P, Rowan M. Qualitative studies. Their role in medical research. Can Fam Physician. 1998 Nov;44:2453-8. [PMC free article].

- Creswell J.W.. Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.), Sage Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi (2007).

- Cleland JA. The qualitative orientation in medical education research. Korean J Med Educ. 2017 Jun;29(2):61-71. [PMC free article. [CrossRef]

- Bryant A. Grounded theory and grounded theorizing – Pragmatism in research practice. Oxford University Press, USA, 2017.

- Ligita, T., Harvey, N., Wicking, K., Nurjannah, I., and Francis, K. A practical example of using theoretical sampling throughout a grounded theory study A methodological paper. Qualitative Research Journal Vol. 20 No. 1, 2020 pp. 116-126.

- Shaheen, M., Sudeepta Pradhan and Ranajee 2019. Sampling in Qualitative Research chapter 2.

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field methods, 18(1), 59-82.

- Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2010). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychology and health, 25(10), 1229-1245. [CrossRef]

- Coenen, M., Stamm, T. A., Stucki, G., & Cieza, A. (2012). Individual interviews and focus groups in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A comparison of two qualitative methods. Quality of life research, 21, 359-370. [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C. S., Georgiou, M., & Perdikogianni, M. (2017). A comparative method for themes saturation (CoMeTS) in qualitative interviews. Qualitative research, 17(5), 571-588. [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social science & medicine, 292, 114523. [CrossRef]

- Morse J.M. Vol. 25. Sage Publications Sage CA; Los Angeles, CA: 2015. pp. 587–588. (Data were saturated).

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S. et al. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol 18, 148 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Mwita K. Factors influencing data saturation in qualitative studies. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science. 2022;11(4):414–420. 2147-4478.

- Rahimi S, Khatooni M. Saturation in qualitative research: An evolutionary concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2024 Jan 5;6:100174. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nurs. Plus. Open. 2016, 2, 8–14.

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.;Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907.

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity. University of California,. ISBN: 0686248929 (br.).

- Charmaz K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Constructing+grounded+theory%3A+A+practical+guide+through+qualitative+analysis&author=K.+Charmaz&publication_year=2006.

- Urquhart, C. (2022). Grounded theory for qualitative research: A practical guide. Grounded Theory for Qualitative Research, 1-100.

- Ünlü Z. (2015). Exploring teacher-student classroom feedback interactions on EAP writing: A Grounded theory approach [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Warwick Centre for Applied Linguistics. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Exploring+teacher-student+classroom+feedback+interactions+on+EAP+writing%3A+A+Grounded+theory+approach&author=Z.+%C3%9Cnl%C3%BC&publication_year=2015.

- Ünlü Z. (2018). Grounded theory method in applied linguistics. Bogazici University Journal of Education, 35(2), 51–66. dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/buje/issue/44507/554744 https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Grounded+theory+method+in+applied+linguistics&author=Z.+%C3%9Cnl%C3%BC&publication_year=2018&pages=51-66.

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research : Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications.

- Qureshi, H. A., & Ünlü, Z. (2020). Beyond the Paradigm Conflicts: A Four-Step Coding Instrument for Grounded Theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Bai,L., Gong,S., Huang, L., 2020. Determinants of consumer food safety self-protection behavior– an analysis using grounded theory. Food Control 113 (2020) 107198. [CrossRef]

- Walker, D., & Myrick, F. (2006). Grounded theory: An exploration of process and procedure. Qualitative Health Research, 16(4), 547. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, P., Ghofranipour, F., Ahmadi, F., Hosseinpanah, F., Montazeri, A., Jalalifarahani, S., et al. (2011). Barriers to a healthy lifestyle among obese adolescents: A qualitative study from Iran. International Journal of Public Health, 56(2), 181–189. [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. (2015). Profiling consumers who are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute in a Western society. Food Quality and Preference, 39, 147–155.

- Myers, G., & Pettigrew, S. (2018). A qualitative exploration of the factors underlying seniors' receptiveness to entomophagy. Food Research International, 103, 163–169. [CrossRef]

- Piha, S., Pohjanheimo, T., Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A., Křečková, Z., & Otterbring, T. (2018). The effects of consumer knowledge on the willingness to buy insect food: An exploratory cross-regional study in northern and Central Europe. Food Quality and Preference, 70, 1–10.

- Giotis,T., Drichoutis, A.C., 2021. Consumer acceptance and willingness to pay for direct and indirect entomophagy, Q Open, Volume 1, Issue 2, 2021, qoab015, . [CrossRef]

- Casas, R.M.; Hernández Campoy, J.M. A sociolinguistic approach to the study of idioms: Some anthropolinguistic sketches. Cuad. Filol. Ingl. 1995, 4, 43–61.

- Meyer-Rochow, V.B., Kejonen, A. (2020). Could Western Attitudes towards Edible Insects Possibly be Influenced by Idioms Containing Unfavourable References to Insects, Spiders and other Invertebrates? Foods 2020, 9, 172;. [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G. Entomophagy and Italian consumers: An exploratory analysis. Prog. Nutr. 2015, 17, 311–316.

- Legendre, T.S., and Baker, M.A. (2021) The gateway bug to edible insect consumption: interactions between message framing, celebrity endorsement and online social support. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management Vol. 33 No. 5, 2021 pp. 1810-1829 © Emerald Publishing Limited 0959-6119. [CrossRef]

- Halloran A., Mnke-Svendsen C., Van Huis A., Vantomme P. (2014) “Insects in the human food chain: global status and opportunities,” Food Chain, 4: 103–18. [CrossRef]

- Deroy, O.; Reade, B.; Spence, C. The insectivore's dilemma, and how to take the West out of it. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 44, 44–55.

- Lombardi, A.; Vecchio, R.; Borrello, M.; Caracciolo, F.; Cembalo, L. Willingness to pay for insect-based food: The role of information and carrier. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 72, 177–187. [CrossRef]

- Caparros Megido, R.; Gierts, C.; Blecker, C.; Brostaux, Y.; Haubruge, E.; Alabi, T.; Francis, F. Consumer acceptance of insect-based alternative meat products in Western countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 237–243. [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D., Sogari, G., Veneziani, M., Simoni, E., & Mora, C. (2017). Eating novel foods: An application of the theory of planned behaviour to predict the consumption of an insect-based product. Food Quality and Preference, 59, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.; Moruzzo, R.; Riccioli, F.; Paci, G. European consumers' readiness to adopt insects as food. A review. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 661–678. [CrossRef]

- Zielinska, E.; Zielinski, D.; Karas, M.; Jakubczyk, A. Exploration of consumer acceptance of insects as food in Poland. J. Insects Food Feed 2020, 6, 383–392. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann C., Siegrist M. (2016) “Becoming an insectivore: results of an experiment,” Food Quality and Preference, 51: 118–22.

- House J. (2016) “Consumer acceptance of insect-based foods in the Netherlands: academic and commercial implications,” Appetite, 107: 47–58. [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer F.S. Insects as Human Food: A Chapter of the Ecology of Man. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2013.

- Hartmann C., Shi J., Giusto A., Siegrist M. The Psychology of Eating Insects: A Cross-Cultural Comparison between Germany and China. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015; 44:148–156. [CrossRef]

- Mishyna M., Chen J., Benjamin O. Sensory Attributes of Edible Insects and Insect-Based Foods—Future Outlooks for Enhancing Consumer Appeal. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020; 95:141–148. [CrossRef]

- Ruby M. B., Rozin P., Chan C. (2015) “Determinants of willingness to eat insects in the USA and India,” Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 1(3): 215–25.

- Sheppard, B., & Frazer, P. (2015). Comparing social and intellectual appeals to reduce disgust of eating crickets. Studies in Arts and Humanities, 1(2), 4–23. [CrossRef]

- Shockley, M., Allen, R. N., & Gracer, D. (2017). Product development and promotion. Insects as food and feed: From production to consumption (pp. 398–419). Wageningen, The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Sogari, Giovanni & Menozzi, Davide & Mora, Cristina. (2016). Exploring young foodies׳ knowledge and attitude regarding entomophagy: A qualitative study in Italy. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science. 7. [CrossRef]

- Nystrand, B. T., Olsen, S. O. (2020). Consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward consuming functional foods in Norway. Food Quality and Preference, 80, 103827. [CrossRef]

- Bae Y, Choi J. Consumer acceptance of edible insect foods: an application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Nutr Res Pract. 2021 Feb;15(1):122-135. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Teodorescu, K., & Erev, I. (2014). On the decision to explore new alternatives: The coexistence of under-and over-exploration. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 27(2), 109-123.

- Lensvelt, E.; Steenbekkers, L.P.A. Exploring Consumer Acceptance of Entomophagy: A Survey and Experiment in Australia and the Netherlands. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 543–561. [CrossRef]

- Cramer, L., & Antonides, G. (2011). Endowment effects for hedonic and utilitarian food products. Food quality and preference, 22(1), 3-10. [CrossRef]

- Adegboye, A. R. A., Bawa, M., Keith, R., Twefik, S., & Tewfik, I. (2021). Edible Insects: Sustainable nutrient-rich foods to tackle food insecurity and malnutrition. World Nutrition, 12(4), 176-189. [CrossRef]

- Puzari, M. (2021). Prospects of entomophagy. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 41(3), 1989-1992.

- Peshuk, L. V., Kyrylov, Y. E., Ibatullin, I. I., & Marenkov, M. (2022). Entomophagy as a promising and new protein source of the future for solving food and fodder security problems. Journal of Chemistry and Technologies, 30(4), 627-638.

- Shirolapov, I. V., Maslova, O. A., Barashkina, K. M., Komarova, Y. S., & Pyatin, V. F. (2023). Entomophagy as an alternative source of protein and a new food strategy. Kazan medical journal. [CrossRef]

- Doi, H., Gałęcki, R., & Mulia, R. N. (2021). The merits of entomophagy in the post COVID-19 world. Trends in food science & technology, 110, 849-854. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).