3.1. The Geomancy of Ancestor halls

This section presents the geomantic characteristics of the ancestral halls, specifically including the orientation of the halls themselves, the relationship between the halls and nearby mountains, as well as the relationship between the halls and the villages.

Figure 6.

the orientation of ancestral halls.

Figure 6.

the orientation of ancestral halls.

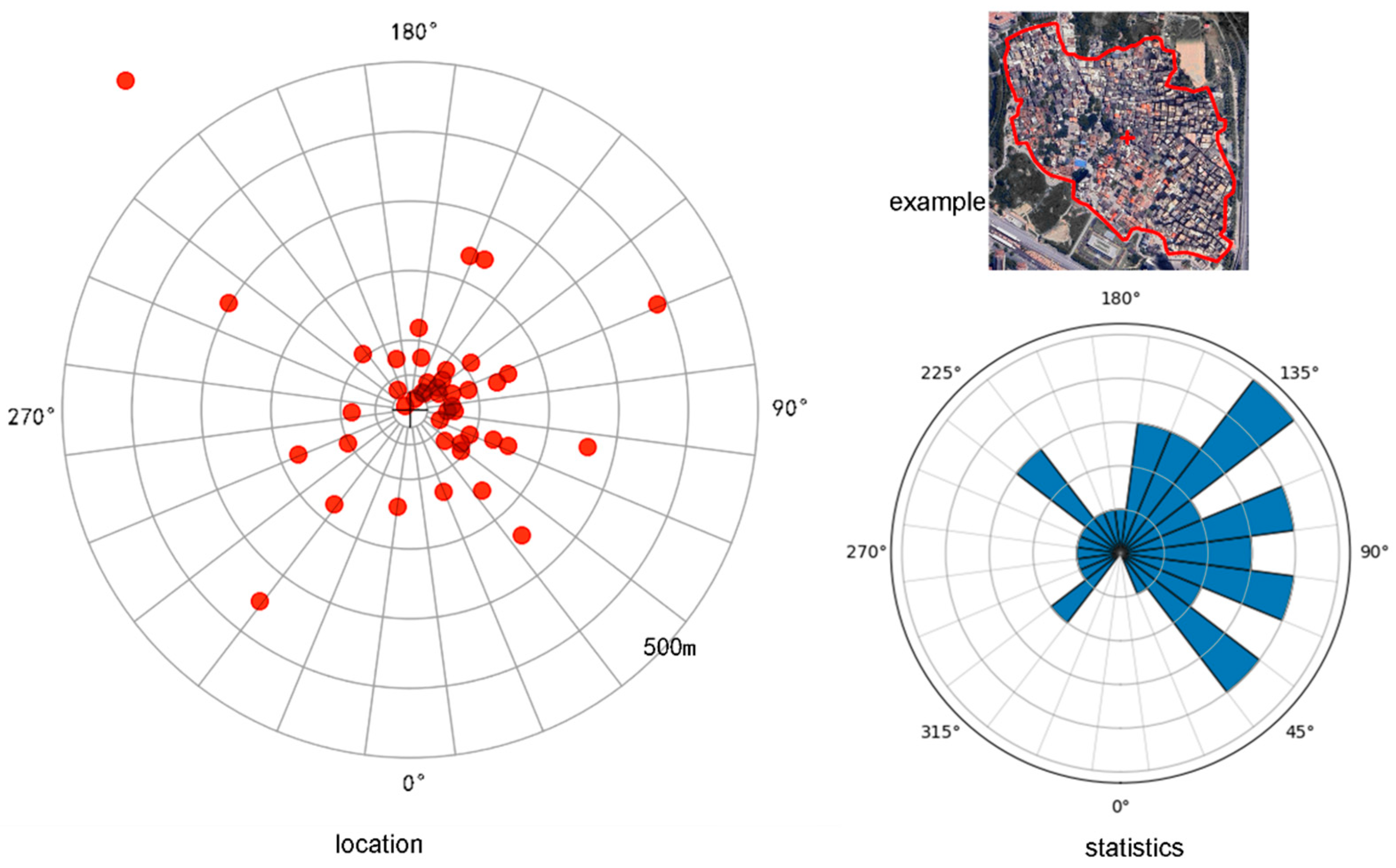

In terms of the orientation of ancestral halls, there are halls facing various directions, with the highest number (8) oriented 15°south of west. In northern China and the Yangtze River basin, ancestral halls are often roughly oriented to face south, as this facilitates better lighting and the accumulation of southern "Yang energy." However, in southern Fujian, where the latitude is approximately 24°N and very close to the tropics, the region is naturally hot and rainy. As a result, the need for lighting and "Yang energy" is reduced, leading to a wide variety of hall orientations.

Nevertheless, south-facing orientations are still considered favorable, with 11 halls oriented toward the south. However, there are almost no halls facing directly south. This is because, while south-facing directions are generally auspicious, the directly southern "Jia-Wu" direction is considered highly inauspicious, associated with "financial ruin and family destruction." In contrast, 15°south of west, known as "Ding Shan" includes the "Xu-Wu" and "Xin-Wei" directions, which are regarded as highly auspicious. The "Xu-Wu" direction is believed to bring prosperity and wealth to all family branches, while the "Xin-Wei" direction is said to bring thunderous success. Additionally, the region experiences prevailing northeasterly winds in winter, so a slightly westward deviation from south can help reduce the impact of winter winds. However, the feng shui requirements for ancestral hall orientation are often tied to the specific history and aspirations of the family, making the diversity in actual orientations unsurprising.

Using GIS tools, we can calculate which mountain appears relatively highest in the view from each ancestral hall. This mountain usually plays a role in the feng shui considerations of the hall. By mapping the mountain's location onto the 24 cardinal directions of the hall's orientation, it can be observed that mountains are more frequently located behind the hall than in front. Among 45 ancestral halls, 30 have the most prominent mountain situated at the rear. In Chinese feng shui, there has long been a tradition of identifying the "ancestral mountain" or "minor ancestral mountain," with the belief that having such a mountain behind a residence or village is more auspicious. However, when ancestors or feng shui masters selected an ancestral mountain in ancient times, it was common—but not necessarily required—to choose the highest peak in the view. Additionally, feng shui masters often considered a combination of factors, such as having the ancestral mountain at the back while aligning the hall toward specific directions, such as "Ding Mountain." Therefore, the influence of the highest mountain's position is relatively limited.

Figure 7.

nearest mountains and their direction from ancestral halls (from this figure to figure 20, the 0° in compass means the direction of the front gate, not the direction of south.).

Figure 7.

nearest mountains and their direction from ancestral halls (from this figure to figure 20, the 0° in compass means the direction of the front gate, not the direction of south.).

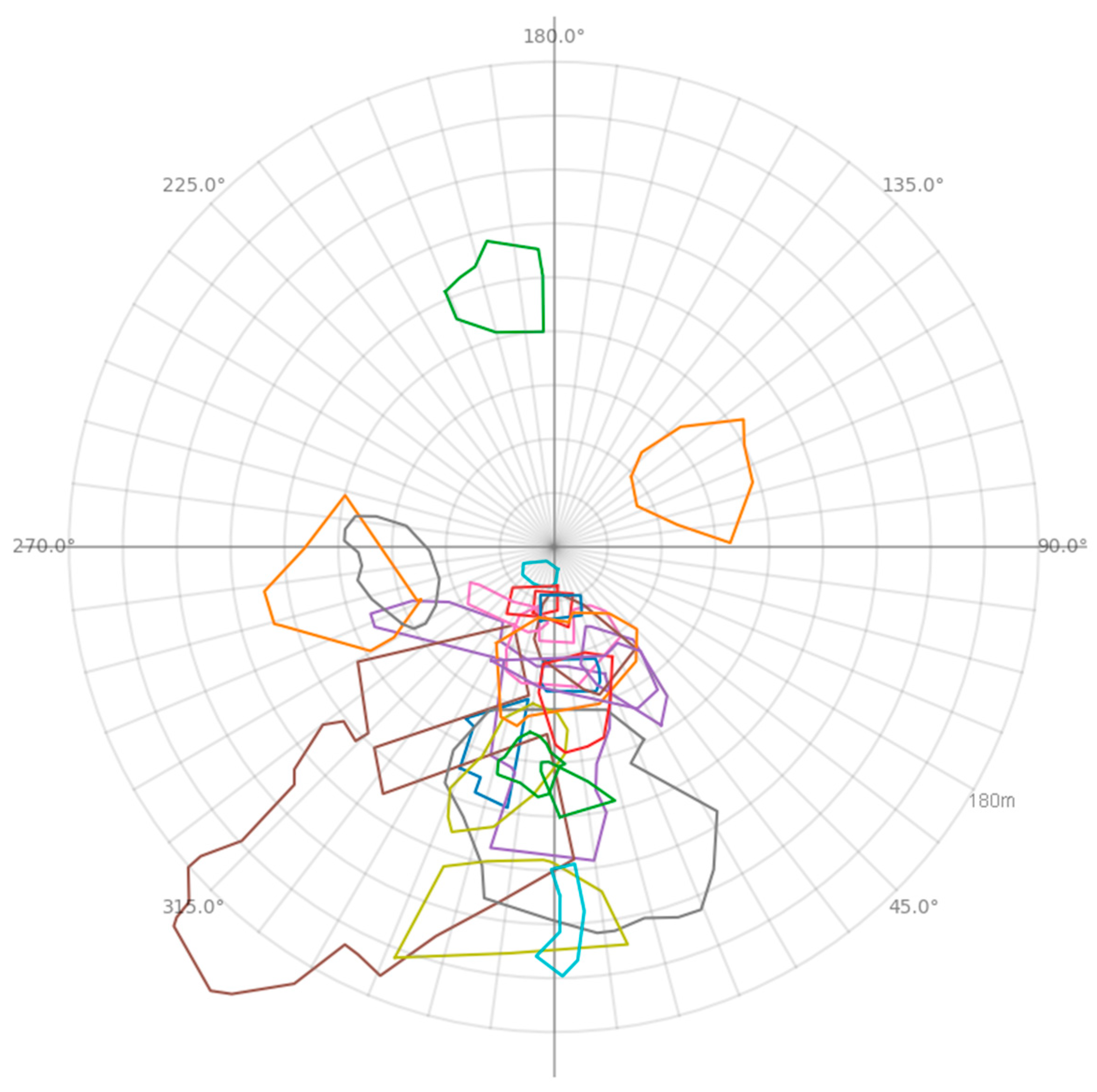

The outline of the village where the ancestral hall is located has been drawn on the map, as shown below. From this, we can extract the geometric center of the village to analyze the relationship between the ancestral hall and the village. It can be observed that the village center may be situated in various directions beyond the front of the ancestral hall, most commonly to the rear left of the hall. Prior to this study, earlier researchers often generalized those ancestral halls were located at the exact center of villages, but this does not appear to be entirely accurate. Notably, no village boundary is found within 40 meters directly behind the ancestral hall, whereas in seven cases, the boundary appears within 40 meters directly in front of the hall. In these villages, the ancestral hall often serves as a gateway, visible just a few steps after entering the village from the outside.

Figure 8.

The outline of villages.

Figure 8.

The outline of villages.

Figure 9.

The outline of villages within 60 meters.

Figure 9.

The outline of villages within 60 meters.

Statistical analysis reveals that the center of a village is often located to the left and backside of the ancestral hall. If we consider that the ancestral hall was constructed earlier than the majority buildings of the village, it can be inferred that newer constructions tend to develop towards the left and rear of the ancestral hall. This stem from certain feng shui practices aimed at seeking the blessings of ancestors, or perhaps out of reverence, avoiding construction in front of the ancestral hall. Alternatively, it could be due to the orderly division of family property over time, with houses for descendants tending to extend towards the left or rear (considered relatively humble directions). The specific reasons may result from a combination of factors, but these elements collectively contribute to the spatial pattern of the ancestral hall being near the village entrance, with the village itself situated to the left and rear.

Figure 10.

The location of village centers.

Figure 10.

The location of village centers.

3.2. Patterns between Halls and Nature

This section focuses on the spatial pattern characteristics of two natural landscape elements within the village that pertain to the relationship between humans and nature: ponds and trees.

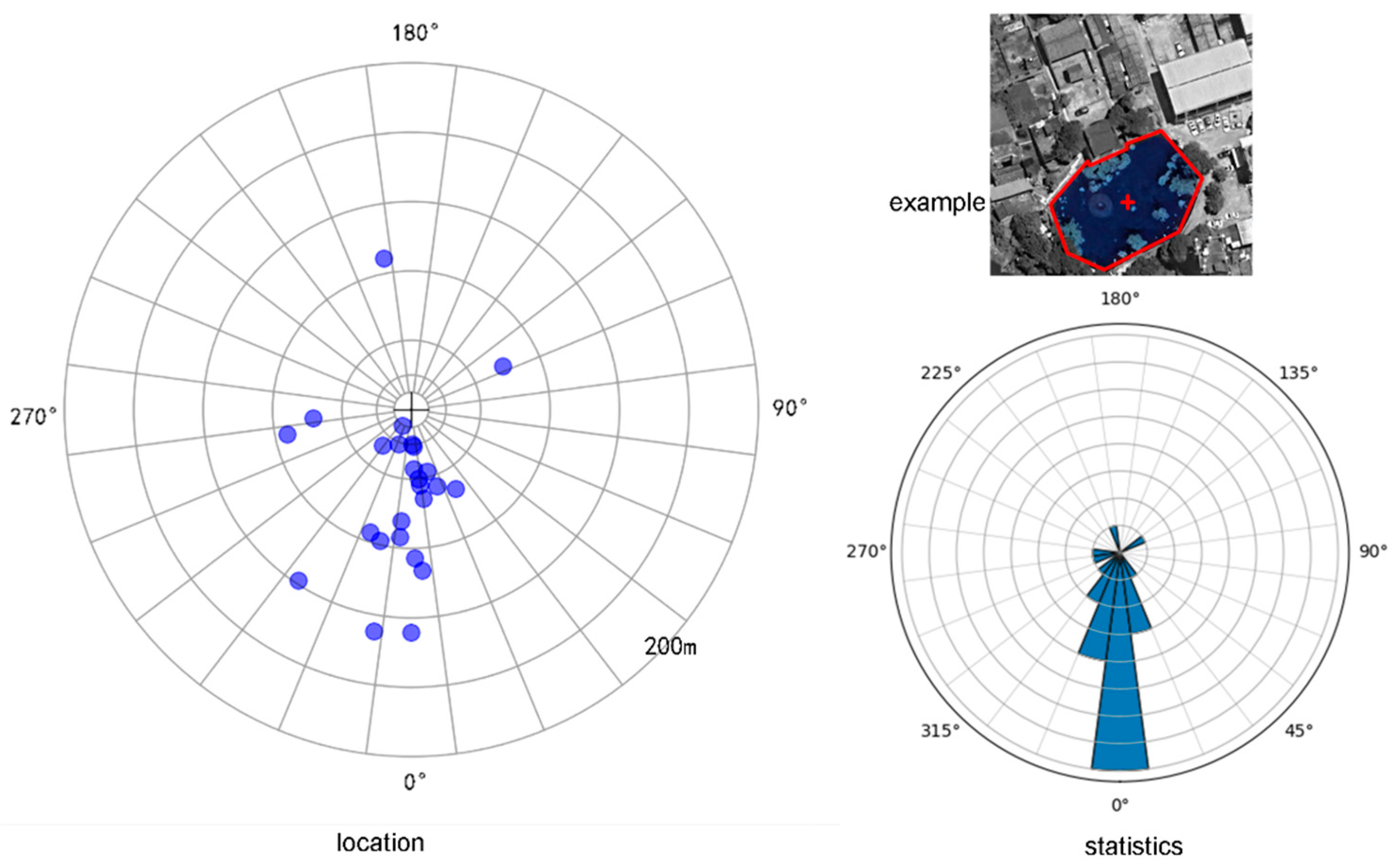

Not every village has a pond near its ancestral hall. In this study, a total of 23 pond outlines were recorded, and their geometric center positions were determined. The relationship between the pond outlines and the orientation of the ancestral halls is shown in the diagram below. It can be observed that the vast majority, 19 ponds, are located in front of the ancestral halls, with the centers of 15 ponds situated within the Kan trigram (i.e., within 45° directly in front). In terms of distance, approximately half of the pond shorelines are within 40 meters in front of the ancestral halls.

Figure 11.

The outline of ponds.

Figure 11.

The outline of ponds.

Ancient Chinese architecture was predominantly constructed using wooden structures. The ponds within villages could serve as a water source, playing a role in fire prevention, while also being used by villagers for washing clothes (drinking water generally came from more sanitary wells). Some earlier studies also indicate that ponds contribute to the formation of localized microclimates, improving livability. Ponds specifically located in front of ancestral halls are referred to as "feng shui ponds" and are believed to have the function of attracting wealth. Feng shui ponds can be categorized into "yang ponds" and "yin ponds." Yang ponds are built in certain locations within villages or residential areas to enhance the feng shui conditions of the living environment, while yin ponds are mainly constructed in front of ancestral halls, temples, or tombs.

Figure 12.

The location of pond centers.

Figure 12.

The location of pond centers.

Village feng shui ponds are typically formed by diverting water from natural lakes or rivers and then enhancing them with artificial construction. In cases where natural conditions are not available, ponds are created through manual excavation, a process commonly referred to as "water replenishment." In recent years, local governments have taken the lead in maintaining water quality and repairing the shoreline of these ponds, improving their safety for children and eliminating unpleasant odors or mosquito breeding. For instance, the feng shui pond located in Xiheng is equipped with stone railings and features aquatic plants, contributing to the beautification of the village environment.

Figure 13.

Pond in Xiheng village, covered with lotus.

Figure 13.

Pond in Xiheng village, covered with lotus.

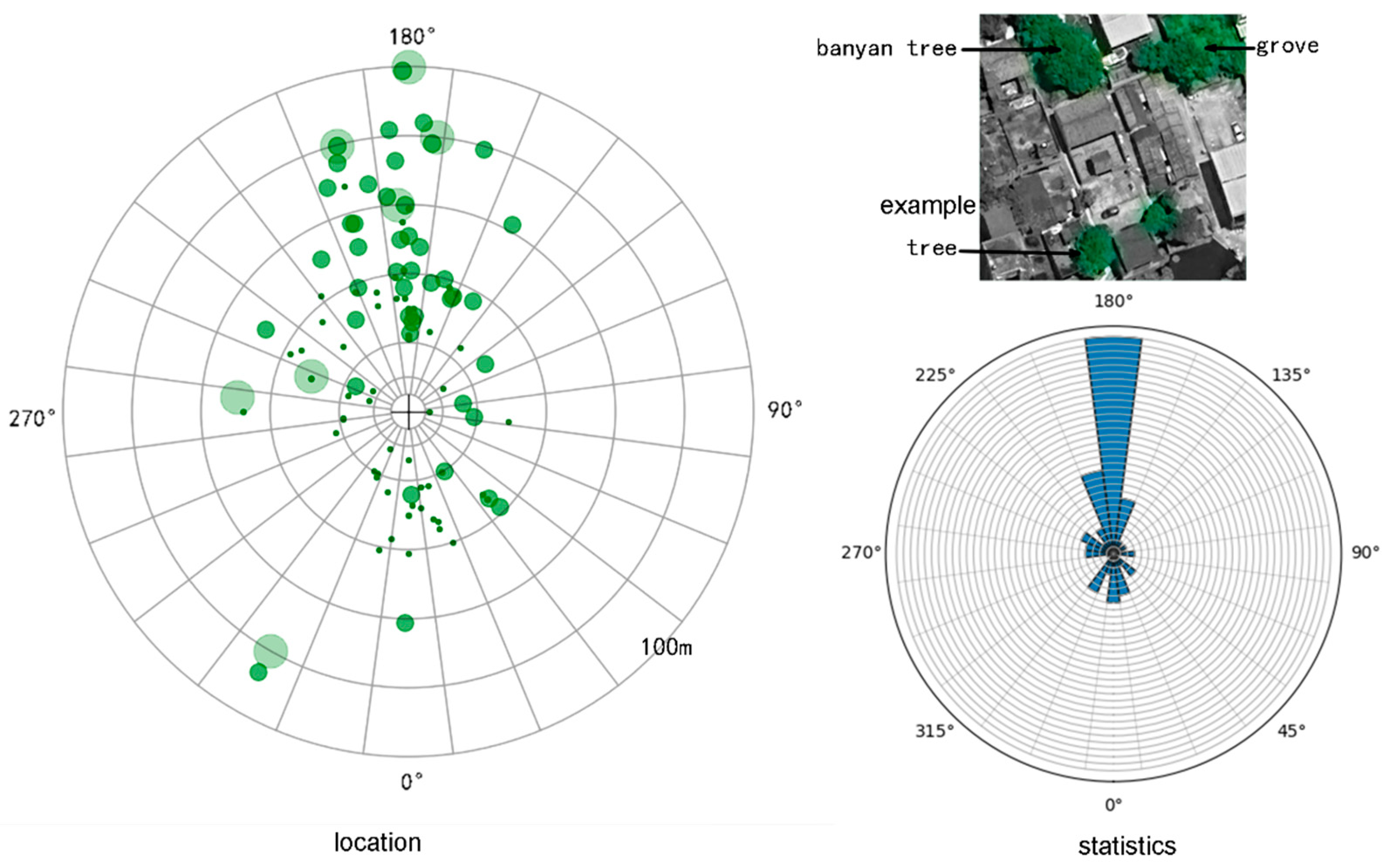

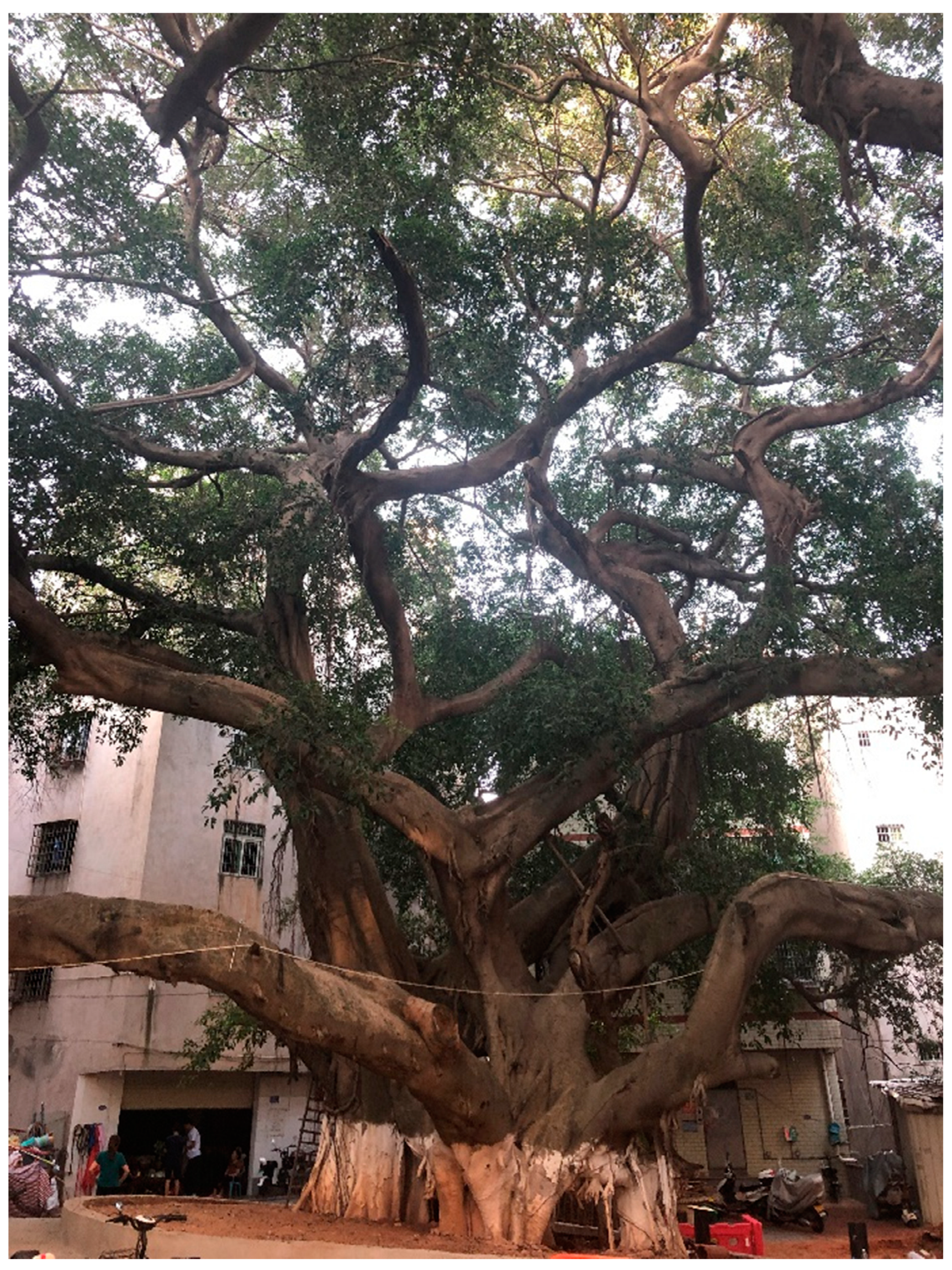

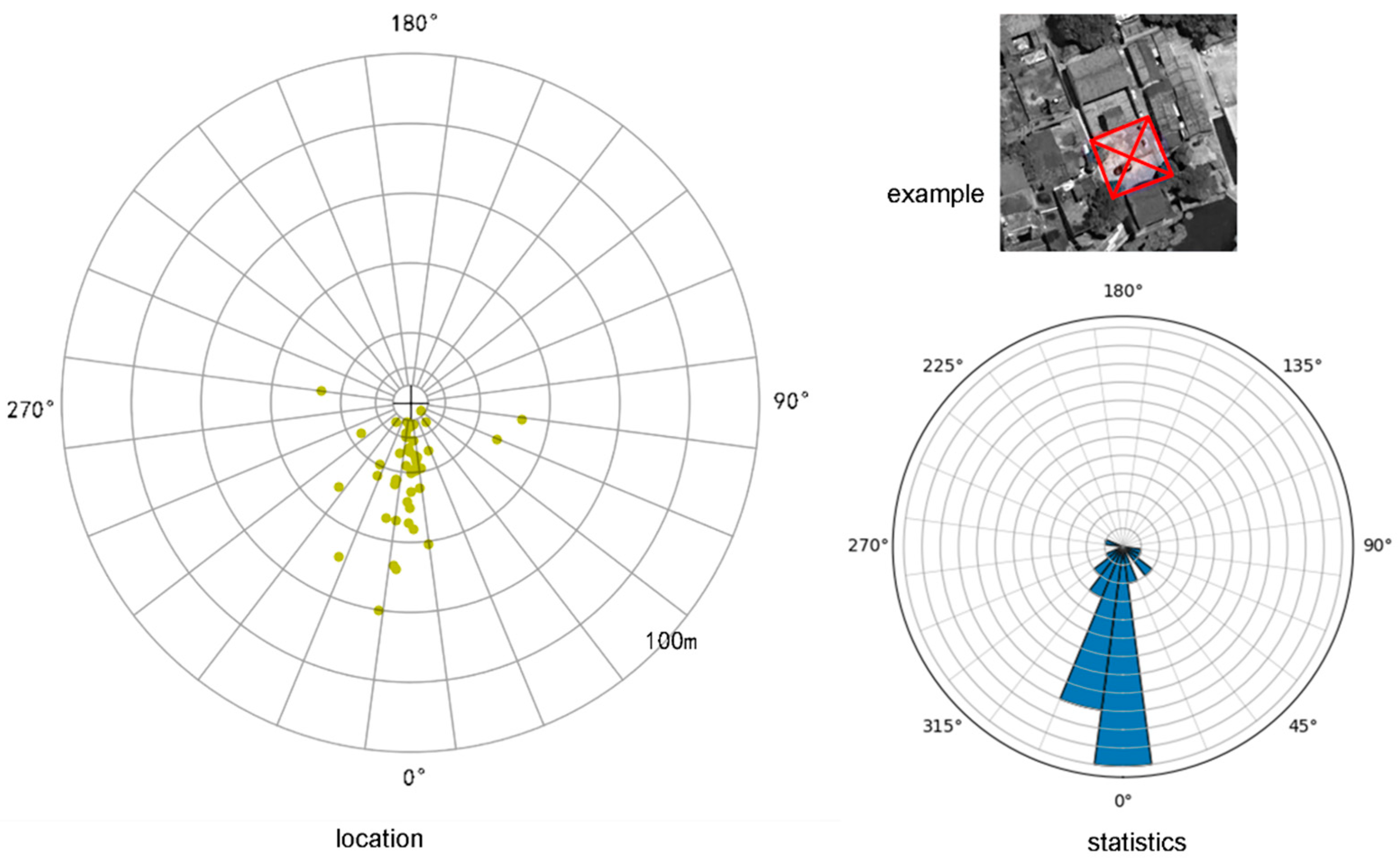

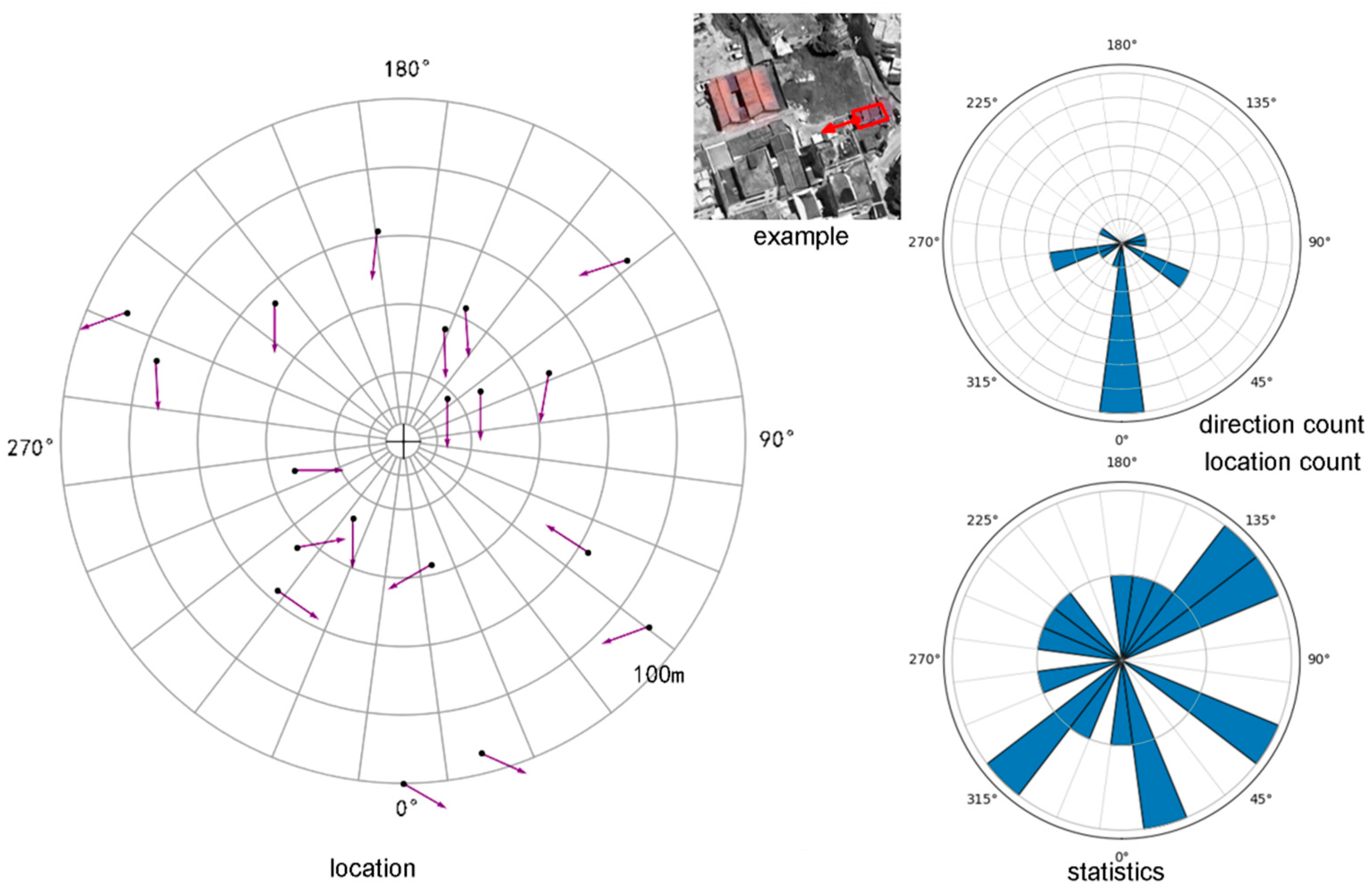

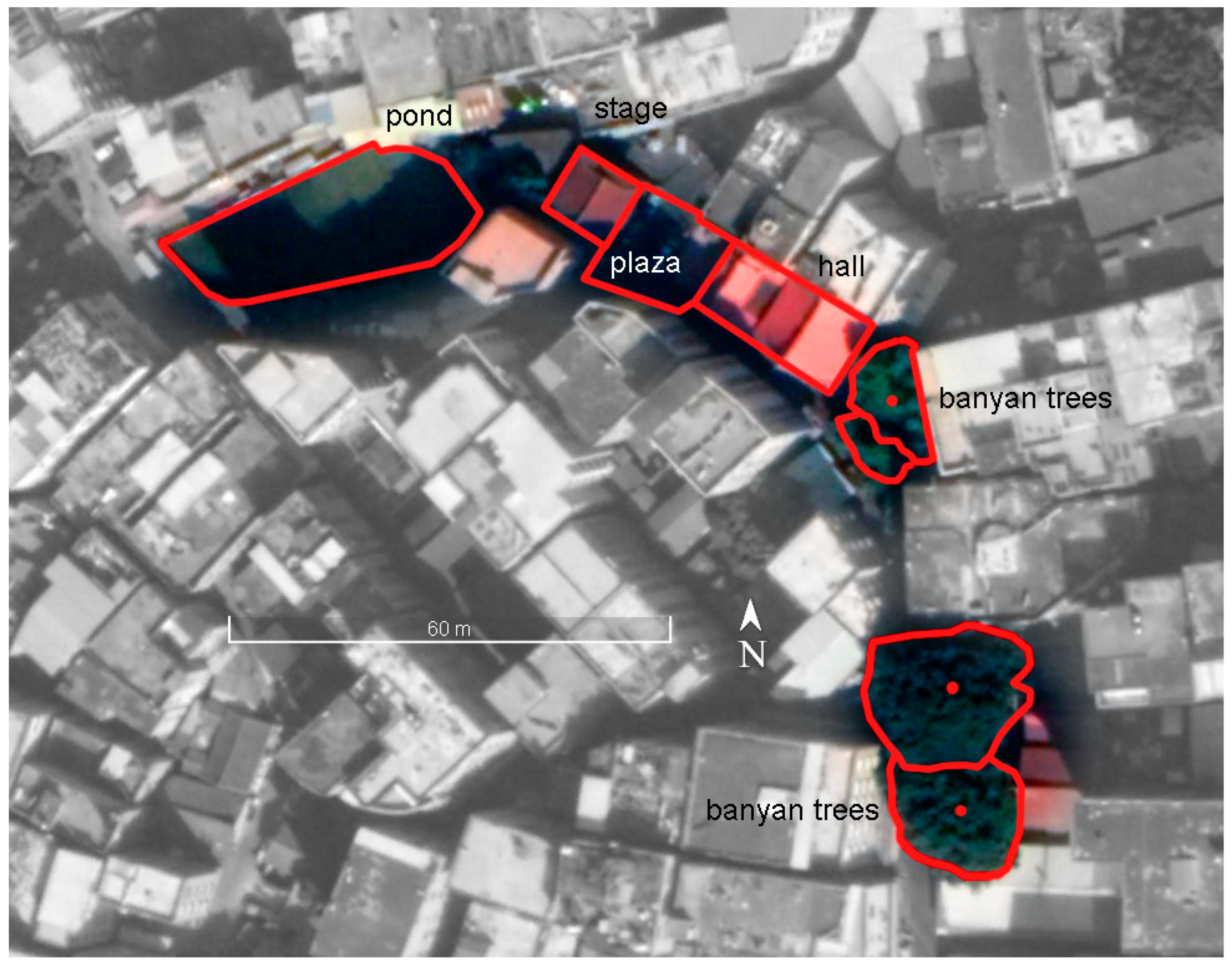

The village contains a diverse range of trees, making it difficult to conduct a comprehensive inventory. This study focuses on documenting all types of trees located within 40 meters of the ancestral hall's gate, as well as ancient trees over 80 years old or groves consisting of more than five trees located within 100 meters of the ancestral hall's gate. Their locations are represented in the diagram with small dots, large dots, and translucent circles. In this study, all ancient trees are banyan trees.

Figure 14.

The location of trees.

Figure 14.

The location of trees.

Statistical analysis reveals that the majority of trees, particularly banyan trees, are concentrated directly behind ancestral halls. These trees are generally regarded as Feng-shui trees, most of which are over a century old, with some even boasting several hundred years of age. Although banyan trees are native to southern Fujian, they are not commonly found in the wild on the plains. Therefore, every banyan tree in these villages was planted by the ancestors of the community.

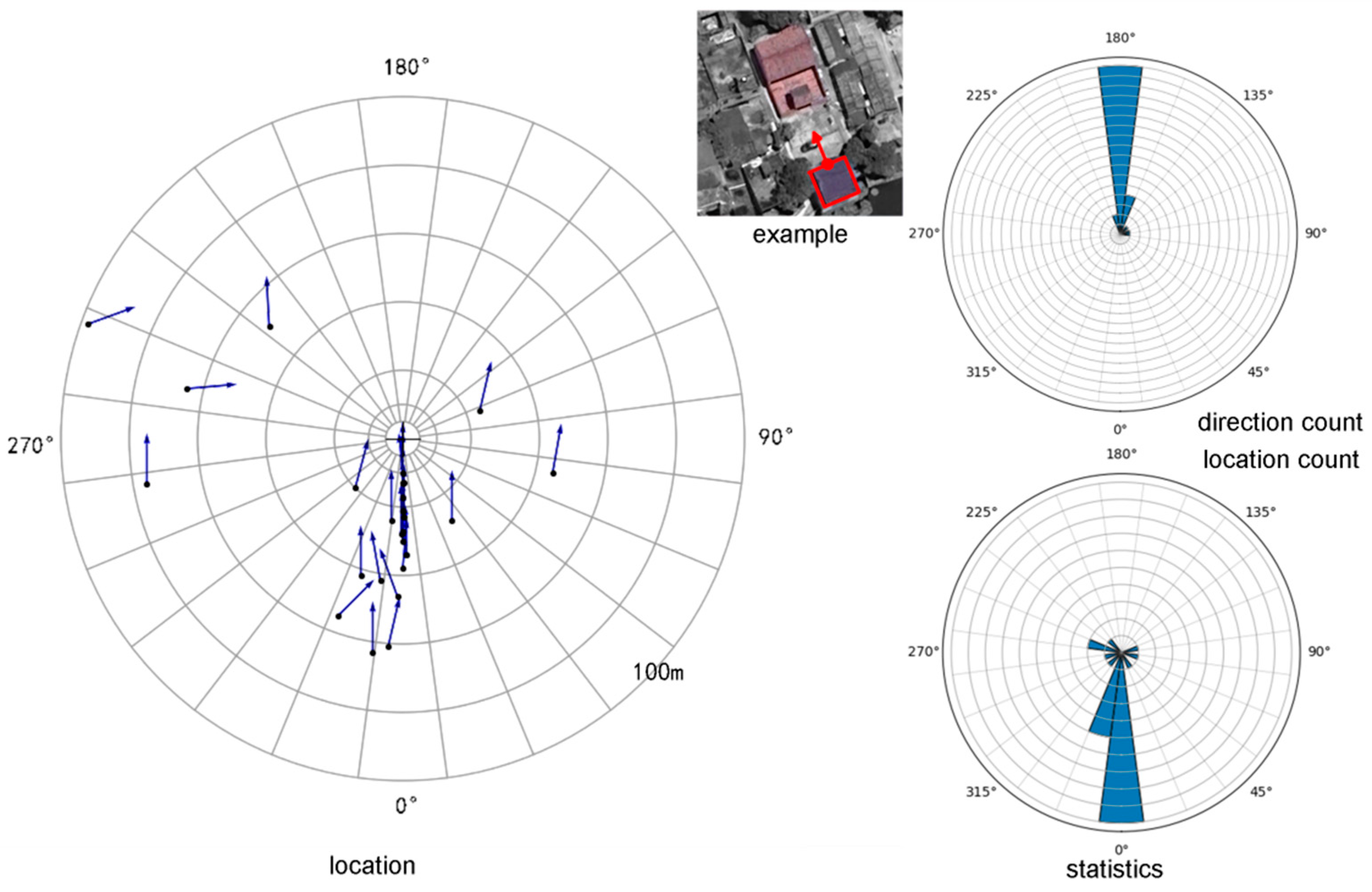

From a historical and cultural perspective, banyan trees hold profound cultural significance in southern Fujian and are imbued with numerous auspicious Feng Shui connotations, such as symbolizing the prosperity of the village, flourishing populations, longevity, happiness, and tranquility, as well as wealth and honor. In religious beliefs, banyan trees are thought to possess spiritual qualities and are believed to protect villagers, which is why many rituals are conducted beneath them, often accompanied by small shrines at their base. Accordingly, planting banyan trees behind ancestral halls is seen as a way to channel their spiritual power to safeguard the clan. As a result, in many stories from villages in Fujian, ancient trees and ancestral homes are mentioned together. For instance, the ancestral hall in Guanzhen Village is said to have been built 500 years ago, with the banyan tree planted around the same time. Once the banyan tree grows tall and expansive, it provides a large shaded area beneath it, offering a cool retreat for villagers during the summer. This reflects the foresight of the ancestors in planning for harmonious coexistence between humans and nature.

Figure 15.

The great banyan tree in Dong’an village.

Figure 15.

The great banyan tree in Dong’an village.

Some of the forests located closer to ancestral halls serve as Feng-shui forests, functioning similarly to Feng-shui ponds. By positioning a forest in an appropriate location, it can block specific directional "Sha Qi" (negative energy), thereby protecting the clan from misfortune. Sha Qi often corresponds to a straight road or an open area, which in practical terms reflects the need to enhance privacy, avoid traffic noise or shield against strong winds. Most of the Feng Shui forests observed in this study consist of longan trees. This type of tree is well-suited to the local climate, requires minimal maintenance, and produces longan fruit. In addition to providing Feng Shui benefits, it also offers economic value.

3.3. Artificial environment

This section discusses the human-made features in the village, including the square in front of the ancestral hall, as well as three types of buildings with distinct functions and backgrounds: temples, communes, and drama stages.

The open space in front of ancestral halls naturally aligns with feng shui principles, ensuring smooth energy flow and preventing any blockage of fortune. However, its primary purpose is to serve as a communal gathering area for village life, functioning similarly to the open spaces in front of churches in Western villages. During ancestral worship ceremonies, this plaza can be used for setting off firecrackers, erecting temporary structures, and placing offerings. From images, it can be observed that while a few plazas may extend to the sides or even the rear of the ancestral hall to increase their overall size, most plazas are strictly aligned with the direction of the main entrance of the hall, forming a rectangular space in front of it. These plazas vary in length from 5 to 50 meters, with widths generally ranging from 15 to 25 meters. The vast majority of these plazas are located in the Wu Shan or Ding Shan directions relative to the ancestral hall, meaning they either strictly follow the hall’s central axis or deviate by 10 to 20 degrees toward the more auspicious Ding Shan direction.

Figure 16.

The outline of plazas.

Figure 16.

The outline of plazas.

Figure 17.

The location of plaza centers.

Figure 17.

The location of plaza centers.

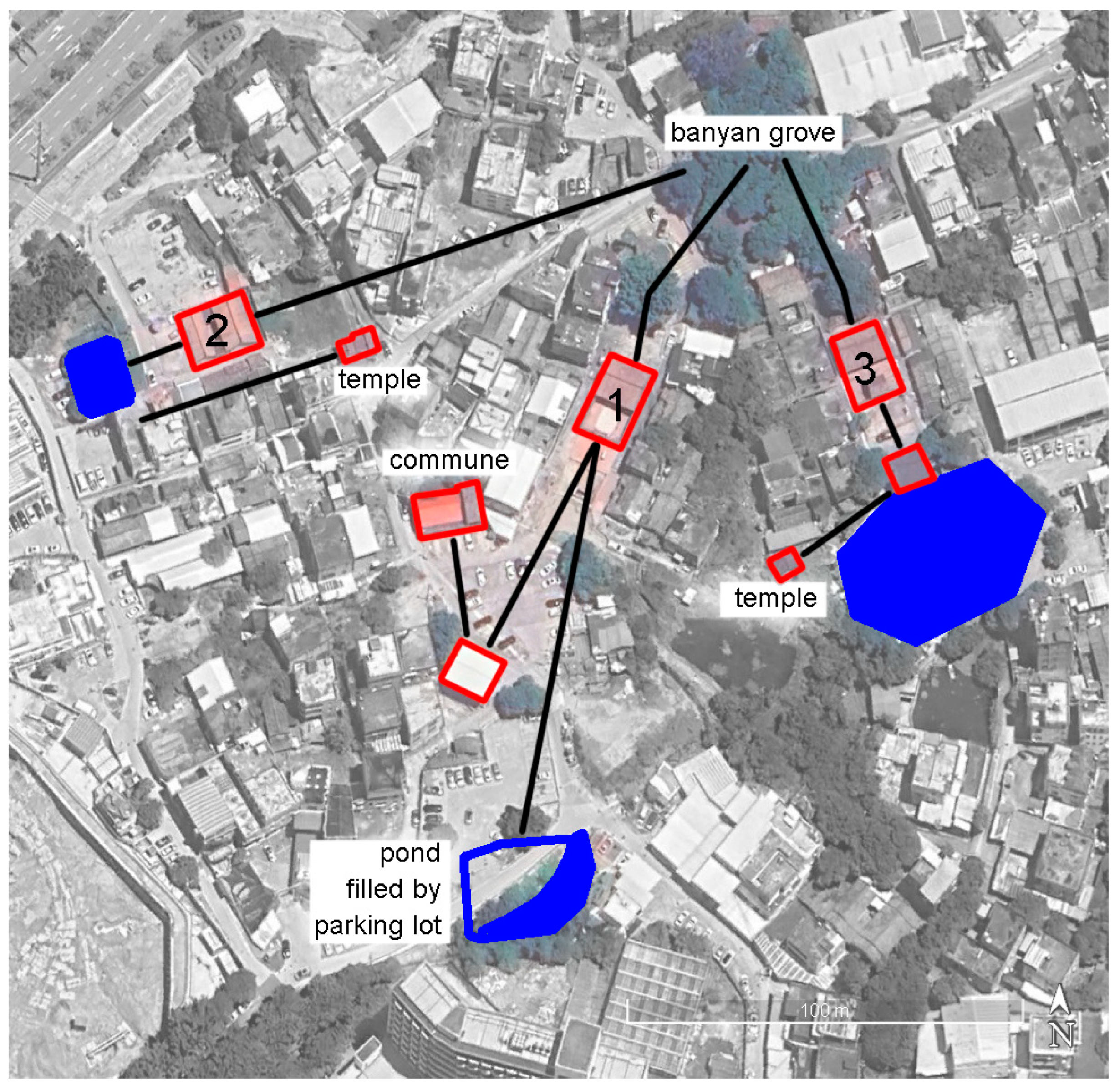

Ancestral halls are the physical embodiment of ancestor worship, while in the belief system of the southern Fujian, the worship of deities also holds significant importance. Temples serve as the places where these deities are enshrined. Some villages have larger, independent temples built on their outskirts, which attract worshippers from a broader area. These temples are designed with their own distinct spatial axes and considerations of feng shui. This article, however, focuses on temples located within close proximity to ancestral halls (within 100 meters). The deities enshrined in these smaller temples often serve as guardian spirits for the village or clan.

Figure 18.

The location of temples.

Figure 18.

The location of temples.

Figure 18 illustrates the location and orientation of temples near the ancestral hall. It can be observed that the distribution of temple locations does not follow an obvious pattern, but a considerable number of temples share the same orientation as the ancestral hall. There are two possible explanations for this: First, for nearby locations, favorable Feng Shui orientations are often similar, leading both the ancestral hall and the temples to adopt this specific orientation. Second, after the ancestral hall was established, the village developed a fixed architectural layout, standardizing the orientation of nearby buildings. When temples were later integrated into this layout, they tended to align their orientation with that of the ancestral hall. Regardless of the explanation, the practice of temples and ancestral halls adopting the same orientation is indeed a common spatial pattern in Jimei villages.

The structures aligned in orientation are not limited to temples but also include an object we had not previously envisioned: commune buildings. People's communes were a unique architectural type during the socialist transformation of the 1950~1970s. Due to the reorganization of village administrative units at that time, not every village necessarily had a commune building, and some of these buildings have since been demolished. Among the nine remaining commune structures located near ancestral halls, five exhibit the characteristic of sharing the same orientation as the ancestral halls (

Figure 19). Since ancestral halls predate commune buildings, it is evident that the orientation of these commune structures was directly or indirectly influenced by the ancestral halls. Society in the 1960s was not keen to “feudalistic superstition” so it was impossible for commune buildings to followed ancestral halls’ direction for geomancy reason. It was probably for use the same plaza to gather people or just to satisfying the villagers as they would find commune building showed respect to their tradition in southern Fujian.

Figure 19.

The location of commune.

Figure 19.

The location of commune.

Finally, we turn our focus to a highly functional structure: the drama stage. Among the 45 ancestral halls, 23 are equipped with drama stages. These stages are spaces specifically designated for performances. It is important to understand that while villagers are free to watch the performances, the primary audience for these traditional drama performances is the ancestors and deities[

16]. Therefore, performances are always oriented toward the ancestral hall or temple (

Figure 20). In the past, rural stages in the southern Fujian were often simple setups: either iron frames erected on earthen platforms with curtains draped over them for performances or temporary wooden and bamboo platforms constructed as needed for drama performances. In recent years, the local government has further promoted drama culture by encouraging villages to build permanent drama stages. Most of these stages are meticulously aligned with the central axis of the ancestral hall, positioned at the far end of the square, and directly facing the hall. A smaller number of stages are aligned with nearby temples, having been originally built to honor the deities. In most cases, the ancestral hall, square, and drama stage form a strict axial relationship.

Figure 20.

The location of drama stage.

Figure 20.

The location of drama stage.