1. Foreword

Human settlements expand and contract based on needs such as water, resources, and communal purposes. Protective activities often arise collectively to support the settlement environment. These include conflict resolution, intergroup cooperation, and addressing mutual deficiencies. Fortifications and military heritage developed organically through human interaction and the environment. Defense facilities vary according to terrain—flatlands, mountains, and coastal fortresses. Such fortresses evolved into administrative towns connected to their surroundings. They formed integrated defense systems for emergencies like war and famine. The capital fortifications of Hanyang in Korea exemplify this strategic evolution. Local systems grew into extensive military landscapes along trade and natural routes. These areas are now protected by national laws and recognized globally by UNESCO.

Furthermore, within a regional context, Korean walled towns serve as representative examples of East Asian walled town construction theory from the Zhouli Kaogongji (周禮 考工記) [[

1]], which was ‘Records on the examination of craftsmanship’ is a book on a wide range of fields in artisanry. It dates from the late Spring and Autumn period (春秋, 770 - 5th C. BCE) and is transmitted as the last part of the Confucian Classic Zhouli (周禮). Its theory on walled town construction organically adapts to various geographical and topographical environments while fulfilling unique functions. The town walls in different regions of Korea are typical examples of this. There are many places where the original function of the walled town has been discontinued, and even its remains cannot be confirmed. Korea's Gochang-eupseong, Eonyang-eupseong, Hongju-eupseong, Myeoncheon-eupseong, and Seosan Haemi-eupseong (

Figure 1) have lost their original functions. However, their remains are well preserved and contribute significantly to defining, protecting, and utilizing heritage value today.

In this context, among the Korean walled towns(in Korean Eupseong, in Chinese 邑城), Seosan Haemi-eupseong walled town (hereinafter referred to as ‘Haemi-eupseong’) stands out in terms of research, protection, and utilization of heritage value. The Korea Heritage Service, the central government agency responsible for protecting Korean cultural heritage, describes Haemi-eupseong as follows: From the end of the Goryeo Dynasty (918 AD to 1392 AD), the Japanese took advantage of the chaos in the country to invade the coastal areas and cause massive damage. To effectively suppress this, the fortress was built between the 17th Year of King Taejong's reign (1417) and the 3rd Year of King Sejong's reign (1421) to relocate the Chungcheong Military Command Headquarters, which was then in Deoksan County, to this location. It served as a wall where military authority was exercised for approximately 230 years until the Military Command Headquarters was moved to Cheongju City in the 3rd Year of King Hyojong's reign (1652). Subsequently, when the Military Command Headquarters was relocated to Cheongju, the Haemi County government office was moved to this fortress. Until 1914, it functioned as the Hoseo Regional Left Camp, which was located in the area West of Uirimji Lake (義林池) in Jecheon City, Chungcheongbuk-do Province of Korea, and where a concurrent military commander was stationed, exercising military authority over the Naepo region.

It also results from many years of resistance to the continual invasion of external forces stemming from a specific region's geographical and strategic advantages and abundant resources. The military function at the regional level was the primary concern of the dynasty at that time, developing alongside the administrative function. Additionally, efforts to cultivate and preserve local customs have continued to this day, further enhancing the universal value of Haemi-eupseong.

This study is to analyze Haemi-eupseong as one of Korea's typical walled towns concerning the attributes that reflect the authenticity of ‘the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention’ (hereinafter referred to as ‘Operational Guidelines of World Heritage’) which can be used as good indicators for sustainable heritage conservation management and examine the efforts of the conservation management entity to sustain and utilize this authority by applying the theory and methodology outlined in the ICOMOS Guidelines on Fortifications and Military Heritage (hereinafter referred to as ‘ICOMOS Guidelines’) to Haemi-eupseong. The goal is to explore theoretical approaches to heritage value, develop systematic methods for heritage utilization, and propose strategies for sustainably preserving the importance of heritage.

Figure 1.

Location of Haemi-eupseong in Korea. (Source: GoogleMaps).

Figure 1.

Location of Haemi-eupseong in Korea. (Source: GoogleMaps).

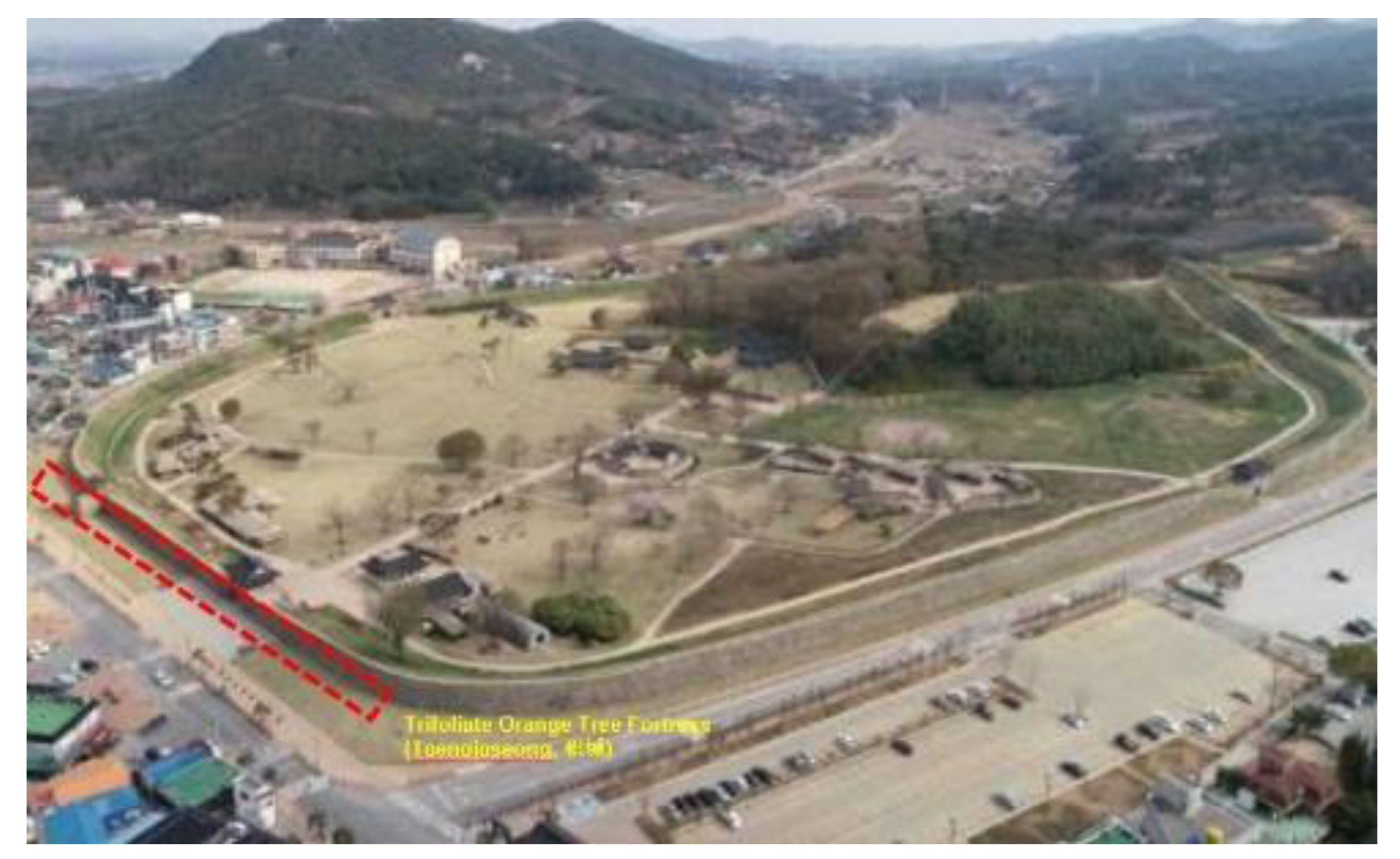

Figure 2.

Aerial View of Haemi-eupseong Walled Town (Source: Korea Heritage Digital Service) [

1].

Figure 2.

Aerial View of Haemi-eupseong Walled Town (Source: Korea Heritage Digital Service) [

1].

2. Research Background and Methodology

Since the operation of the UNESCO World Heritage System, various forms of cultural heritage have emerged, accompanied by charters, principles, and guidelines designed to protect and manage them effectively. In this context, the Operational Guidelines of World Heritage and the ICOMOS Guidelines not only underpin this research but also serve as pivotal documents for future reference and application. (

Table 1)

Meanwhile, the 'seong (城)' used in East Asia generally signifies a fortification. In the context of human settlements and administrative functions, it is interpreted as a city (seongeup, 城邑) or a town (eupseong, 邑城). Walls sometimes surround these cities and towns and sometimes not. For that reason, they are referred to as walled cities or towns. Notably, this character is used for the fortification '城,' although the pronunciation differs in Korea, China, and Japan. For instance, in China, the fortification '城’ is pronounced as ‘cheng'; in Korea, it is pronounced as 'seong'; and in Japan, it is pronounced as 'shiro’.

It is noted that various studies have been conducted by officials and experts related to Haemi-eupseong. In particular, we review the findings from the first conference on the role and status of Haemi-eupseong over time, alongside the regional context of Haemi-eupseong and considerations for future sustainability within the framework of the World Heritage Site. Regarding the Anheungjeong pavilion, a related site, Kim Myung-jin's "Review of the Goryeo Dynasty Objective Anheungjeong (2019)" was consulted, while Nam Do-young's History of Korean Majeong(馬政) (1996) provided insights into the Joseon Majeong system and the Seosan horse farming industry. In military strategic history, research utilized publicly accessible data, such as "Military Strategy in the Goryeo Period, Military Strategy in the Joseon Dynasty" (2006) from the Institute of Military Compilation of the Ministry of National Defence. Additional sources included the Academy of Korean Studies, the Local Culture Electronics Exhibition, and other easily accessible and authoritative online materials. In studying ancient maps, the Daedongyeoji-do Map and Yeoji-do Map were employed to compare and analyze geographical and cultural contexts. Concurrently, photographic data sourced from Google Maps and Google Earth were utilized to examine aerial photographs provided by the Korea Heritage Service.

These efforts are expected to provide direction for research, conservation management, and utilization of the Haemi-eupseong, which is preparing to become a World Heritage site as a fortification heritage, as well as for other regions and even on an international level.

3.1. Attributes that reflect the authenticity of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The Operational Guidelines suggest attributes that reflect the authenticity of the World Heritage Site, such as location and setting; Form and design; materials and substance; use and function; traditions, techniques and management systems; language, and other forms of intangible heritage, but they naturally embody the authenticity of the heritage because the actual tangible and intangible attributes cannot be separated. Specifically, heritage sites should maintain their historical location and layout and preserve their surroundings. The first tangible attribute that reflects authenticity is 'location and setting,' which should not be altered unless it is the only means of preservation. It must be clarified whether and to what extent the property has changed, and boundaries must be established to demonstrate the importance of the property according to its value base. It should be accompanied by an explanation of why the heritage had to settle here in the first place.

The second element of the tangible attribute is the property's ' form and design.' The first condition is that the form and design, continuously evolving from its founding to the present, must be regarded as historical evidence. In other words, assessments must be made regarding the changes in the heritage's form, the extent of change, the fidelity to the original form, and whether the change holds any value.

The third part of the tangible attribute, 'Material and Substance,' refers to the so-called authenticity of the material and recommends that the materials used when the property was created or historically used must be preserved, even if damaged or lost. Additionally, it states that the same materials from that period should ideally be used. In this section, the degree of substitution of the material and the level of superiority between the original state and the conservation measures are crucial factors in assessing the authenticity of the material.

The first intangible attribute that reflects authenticity is 'use and function,' which defines the use or reintroduction of cultural heritage following its historical use and function as a desirable preservation method. It indicates that new uses and functions, whether for heritage communities or various stakeholders, inevitably accompany the loss of historical constructs; therefore, introducing them should be prioritized.

The second intangible attribute is 'Tradition, technique and management system.' Preserving constructs embodying heritage's importance relies on implementing traditional management systems, such as using traditional materials and techniques. In particular, 'related traditional techniques' refer to the conventional methods of creating heritage by producing, manufacturing, processing, and constructing constituent materials that reflect its significance. Meanwhile, 'related traditional techniques' also denote the skilled abilities of craftsmen who employ these essential methods to preserve heritage. Modern materials and technologies are exceptions, used only when they provide considerable property maintenance advantages. Furthermore, it is a protective system for managing a vast and diverse array of continuous heritage. Management traditions can also play a significant role in this area.

Lastly, the 'language and other forms of intangible heritage' of heritage must be regarded as an important attribute underpinning it. This suggests that the social mechanisms supporting the heritage require careful analysis and conservation [

2]. Values representing tangible and intangible attributes that reflect this authenticity can be summarised as Outstanding Universal Value.

3.2. Attributes reflect the characteristics of the fortifications following the ICOMOS Guidelines (2021)

As one of the International Scientific Committees of ICOMOS, an advisory body to UNESCO World Heritage sites, ICOFORT has prepared the ICOMOS Guidelines on Fortifications and Military Heritage with the primary aim of guiding the protection, conservation, and interpretation of fortifications and military heritage from 2007 to 2020. The ICOMOS Guidelines were adopted as an official document by the 2021 General Assembly of ICOMOS and were initially translated and published in English, French, and Spanish. Since then, the ICOMOS Guidelines have been translated into various languages, including Korean, Chinese, Portuguese, and Japanese, and their recognition and utilization have significantly increased, particularly among the national committees of ICOMOS that hold or inscribe fortifications and military heritage on the World Heritage List.

The period categories of fortifications and military heritage addressed in these ICOMOS Guidelines encompass fortifications and military facilities constructed from prehistoric times to the modern era. The guidelines also delineate fortifications and military heritage as structures built by communities using natural elements (such as vegetation and geology) or various materials to defend against attackers. It includes the products of military engineering, arsenals, naval port facilities, harbors, barracks, military bases, testing grounds, quarantine sites, and structures intended for military use or the purpose of attack and defense [

3].

According to this particularity, the main attributes that constitute fortifications and military heritage—interpreted as the outcome of military actions and interactions with nature to achieve a specific purpose—include barriers and protection, command, depth, flanking, and deterrence (

Table 2. ICOMOS, 2021).

3.3. A Study on the Authenticity of Haemi-eupseong

3.3.1. Location and Environment

According to the Annals of King Taejong, Haemi was situated near Gayasan Mountain at the end of the Charyeong Mountains, occupying a strategic position to manage Isanjin (now Deoksan) in the east, Sunseongjin (now Taean) in the West, and Nampojin in the south. (

Figure 3) To the north, Munsu Mountain (文殊山) and Seongwangsan Mountain (聖旺山), which extend from Gaya Mountain, surround Haemi like ear-shape. In other words, the northeastern part of Haemi is fortified with enormous mountains forming a barrier, the Geumgang River to the south, and the sea to the West (

Figure 4). Conversely, the Cheonsuman Bay area between Anmyeondo Island and the interior of Chungcheongnam-do Province naturally creates a military and strategic encirclement, making it an ideal location for command and control functions. For instance, the battle that determined the final outcome during the Goryeo Unification War was the Battle of Unju (Hongseong County, Chungcheongnam-do Province) in September 934 AD, in which Clan Han (韓氏) of Mongungyeok Station made a significant contribution. Consequently, King Taejo Wang Geon awarded him the penname of Daegwang, divided the land of Gogu County, and established Jeonghae County (貞海縣, present-day Haemi-myeon town, Seosan City, Chungcheongnam-do Province) as his official hometown [

4]. This article shows that this area was a strategic military location.

Militarily, this region holds great importance not only economically but also strategically, as it serves as a border area relative to Japan. This significance is highlighted by historical events such as the Japanese pirates during the late Goryeo (

Figure 5) and early Joseon periods and the Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592 (壬辰倭亂). Therefore, it remains crucial both economically and militarily. Notably, the Chungcheong Provincial Military Commander was moved from Isan Town in Deoksan County, east of Gayasan Mountain in Chungcheongnam-do province, to Haemi County in 1421 to effectively counter the threat presented by Japanese pirates. Compared to other towns, coastal areas are primarily occupied by pirates. The Hwaseong Dangseong fortress is situated on the west coast, approximately 60 km north of Haemi-eupseong, recognized as the Tang-China trading port during the Three Kingdoms period, faces challenges in classification as a coastal province due to the reclamation projects undertaken to date.

Regarding the natural environment, the Cheonsuman Bay area on the west coast, where the tidal difference is significant, is a migratory bird habitat, and an ecosystem rich in prey has been created. This area produces a variety of special products compared to other regions, such as grains, fruits, vegetables, flowers, birds, fish, shellfish, medicinal herbs, minerals, and crafts, due to the influence of the organic yellow soil and the cool West Sea breeze. The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, dated 21 July 1832 (King Sunjo 32nd year of reign), records that the British armed merchant ship 'Lord Amherst' came to Changlipo-gu port from the coast of Ganwoldo Island in Seosan and received two heads of cattle, four pigs, 80 chickens, four pickled fish, 20 roots of various vegetables, 20 roots of ginger, 20 roots of green onions, 10 roots of chili peppers, and 20 roots of garlic roots[

7]." As previously reported in the Annals of King Taejong, the Haemi area, surrounded by Gayasan Mt., Munsusan Mt., and Seongwangsan Mt. at the end of the Charyeong Mountain range, was a blessed area with well-developed natural environmental conditions that allowed for the cultivation of various famine crops even in winter, thanks to the nutrients in the loess soil, which blocked the coastal winds. In addition, the coasts of Cheonsuman Mt. and Garorimman Bay have favorable conditions for salt farm development, and in fact, salt production has been carried out on a significant scale from the Joseon Dynasty to the Japanese colonial period and up to the present. In particular, during the Japanese colonial period, the so-called 'monopoly system' was implemented, in which the Government-General controlled the production and sale of salt. This was because salt was so valuable and had a high added value. Before the 1950s, a sack of salt was so expensive that it could be exchanged for a sack of rice, but it is said that it was so valuable that it was difficult to obtain even with an advance payment. Against this backdrop, the West Coast is known to have a huge tidal difference. Because it is challenging to secure agricultural water, coastal reclamation ultimately leads to salt farm development. In this human and natural environment, the administrative functions of Haemi-eupseong, which manages various important elements, and its connection with neighboring regions should be reviewed. Meanwhile, Haemi-eupseong, which satisfies various human and natural conditions, can be inferred to have fulfilled the conditions for performing the function of a military camp as a Hoseo Regional Left Camp. (

Figure 6)

Figure 5.

King Woo's first Year of the Japanese invasion during the Goryeo Dynasty. (Source: Institute of Military History of the Ministry of National Defense, 2006, 321) [

8].

Figure 5.

King Woo's first Year of the Japanese invasion during the Goryeo Dynasty. (Source: Institute of Military History of the Ministry of National Defense, 2006, 321) [

8].

Figure 6.

Location map of major connected sites near Haemi-eupseong (Source: GoogleMaps, author reconstructed) [

9].

Figure 6.

Location map of major connected sites near Haemi-eupseong (Source: GoogleMaps, author reconstructed) [

9].

Historical research on foreign contacts often plays a significant role in establishing property's international and universal value. A representative example of this is World Heritage Namhansanseong in Korea. In the case of Namhansanseong, 17th-century Western records were examined to secure an international and universal perspective. Hendrik Hamel, a Dutch East India Company member, was shipwrecked by a storm while en route to Japan for trade. He drifted to Jeju Island in Korea, was captured by Koreans, taken to the Capital, Hanyang, and eventually returned to his home country via Japan after various adventures. An article about Namhansanseong was published in the 'Hamel Drifter,' which chronicled his journey. This article significantly influenced the concept of 'Emergency Capital,' summarising the value of Namhansanseong as a UNESCO World Heritage Site [

10].

The Anheungjeong (海美安興亭) Pavilion in Haemi County has served as a guesthouse for receiving and seeing off envoys since the Goryeo Dynasty, as confirmed by various historical records in Korea; however, the exact location varies according to the documents describing it. In the Goryeo Do Kyung (高麗圖經) Book by Seo Geung(徐兢), an envoy of the Song Dynasty, it is stated to be located on Mado (馬島) Island [present-day Sinjin-dori Village, Geunheung-myeon District, Taean-gun County, Chungcheongnam-do Province], and its location is noted as "11 ri (one ri is approx.0.39km) east of Haemi County." Among these records, the site of the building still exists at the location mentioned in the "Sinjeung Dongguk Yeoji Seungram(新增東國輿地勝覽)," which adds to the credibility of the information. It is situated at the top of Sinseongbong Ridge near Hanseo University in Sansu Village, Haemi County, Seosan City. These documents pertain to both the land and sea routes. Further analysis is needed to determine whether it was built as a national lodging facility for receiving national guests like modern guest houses, whether it functioned under the same name while being situated on land or sea routes, and to explore records of foreigners' perspectives on this matter.

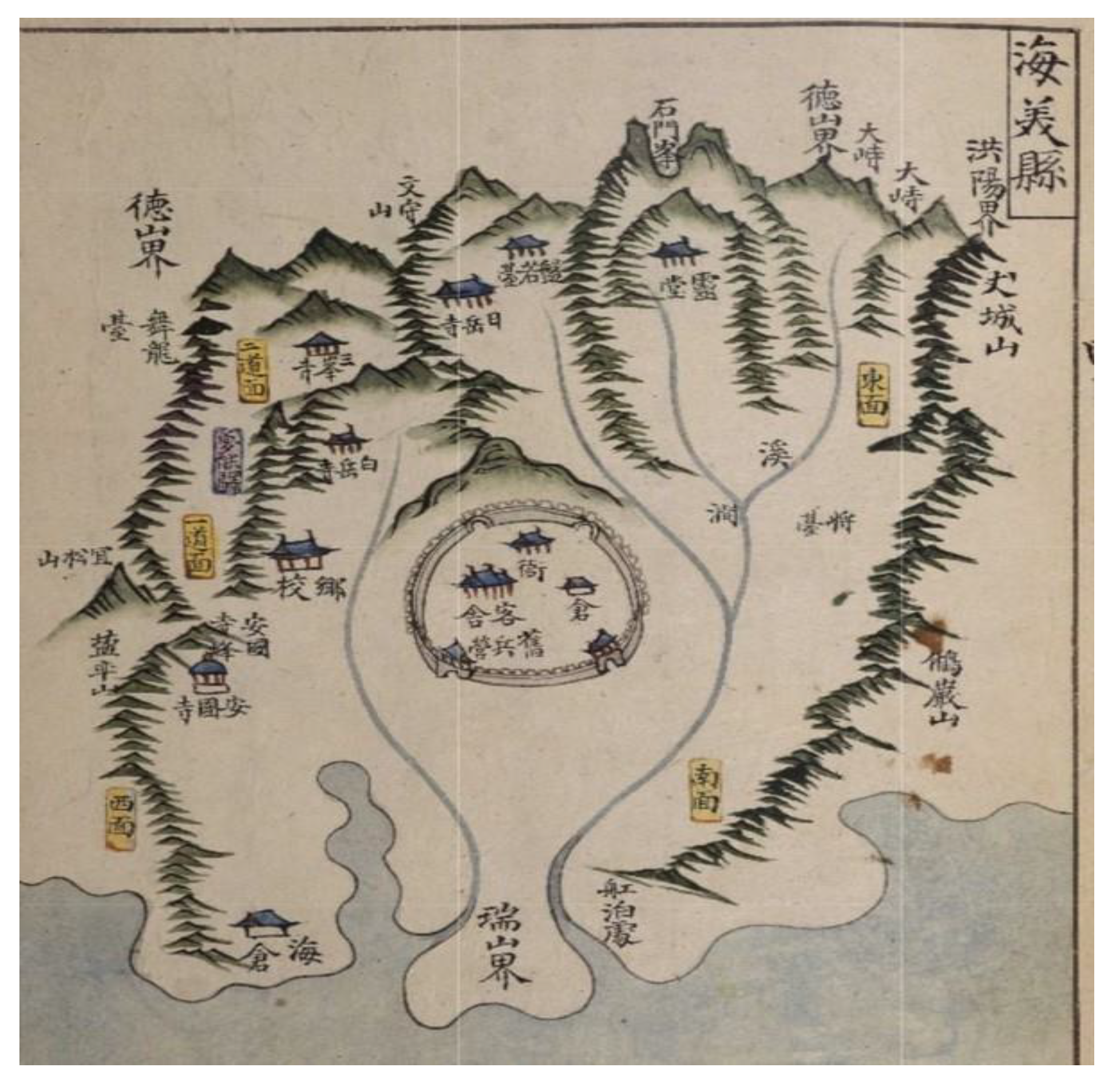

3.3.2. Materials and substances

In the Annals of King Taejong of the Joseon Dynasty, it is stated, “There is a solid stone fortress, and if there is an unexpected disaster, not only the area adjacent to Jeonghai County but also the people living in Gogu, Uncheon town in Hongju County and Dongchon town in Seoju County can enter Stone fortress (石城) and escape the trouble." Suppose one examines the wall of Haemi-eupseong more closely. In that case, one will notice that the fortress consists of a naetak-type structure, where the fortress wall's interior is constructed from soil piled up on a stone axis at an angle, while the exterior is built vertically. In the map of Haemi County of Yeoji-do map, which appears to have been published after 1651, one can observe that the old barracks (舊兵營), the guesthouse (客舍), the storage (倉), and the administrative facility (衙) within Haemi-eupseong are marked, along with two gates and a small ramp connected to the wall. Additionally, a town is densely illustrated on the wall, represented by a closed curve. This seonggaqui or yeojang is also referred to as a parapet (女墻) and is understood to be a variety; it also provides insight into the materials and construction techniques used. This parapet is a feature that can substantiate the composition of the fortification system following the operation of weapons, necessitating further research. In this context, specificity can be secured through the Annals of King Munjong (1451). "Naesangseong fortress in Haemi County has a circumference of 3,352 cheoks and a height of 12 cheoks, and the height of the Yeojang parapet(女墻) is three cheoks. One Cheok is approximately 30.3 cm or 34.5cm. 16 of 18 flanking towers (敵臺) have not yet been built, and four gates have been constructed. There are no attached outworks such as a barbican to the main fortress wall, 688 parapets, 3,626 cheoks of moat surrounding it, and three springs within the fortress," allowing us to verify the size and layout of the structures in Haemi at that time.

The case of Haemi-eupseong showcases a structure of stone, wood, and earthen walls, similar to the construction materials found in other local walled towns. However, it is termed the trifoliate orange fortress (枳城) because it utilizes unique materials that can be visually mistaken by enemies and are exemplary for defense. For instance, there is a valuable article on the trifoliate orange fortress in Volume 12 of the Songnam Japji magazine, under the martial arts category, written by Cho Jae-sam: “The fortress of thorns of the trifoliate orange tree... It is said that the fortress of Tamra (present-day Jeju Island, Korea) was initially constructed from thorns, which have been intertwined for a long time and are as hard as gold and stone. In the late Goryeo Dynasty, Choi Hyung attempted to pull them out but was unsuccessful.”

On the other hand, the Agra Fort, a world heritage site in India, has a double moat system. The secondary moat possesses a unique structure that situates it artificially further inward as a defense against attacks from wild animals. Regarding Namwon-eupseong, a moat exists outside the walled town, accompanied by a separate wall between the moat and the outer wall. Additionally, a Yangmajang (羊馬墻) outwork is utilized as a livestock pen due to the limited space within the fortress walls. Once again, the three-fold system of Haemi-eupseong's moat-trifoliate orange tree-fortress wall serves as an example that is seldom found in other towns.

3.3.3. Form and design

In the Joseon Dynasty, the construction of local towns and villages was fundamentally centered around the palace, which served as the central facility of Hanyang, the capital city. The Hanyangdoseong Capital City wall was developed following the geographical and topographical context, influenced by the ancient palace of Zhouli Kaogongji(周禮 考工記), which embodies the foundational principles of city and palace construction in Chinese and East Asian cultures (

Figure 7). Urban components such as defensive structures, access facilities, roads, waterways, markets, jongmyo ancestral shrines, private offices, residential buildings, and water intake systems were introduced. Regarding defense, the Haemi-eupseong moat extends the traditional defense concept in town. Typically, this walled town in the Joseon Dynasty was fortified with walls approximately 5m high, constructed on slightly elevated hills of varying sizes; however, the defense was inadequate due to the absence of double defense features like moats. In the case of Haemi-eupseong, its rectangular shape is regarded as a form developed in harmony with the topography (

Figure 8). The representative form of the walled towns of the Joseon Dynasty is the square shape, such as the Eonyang-eupseong (1500) and Nakan-eupseong (1424) [

11]. Within the historical narrative of Korean fortresses, which have evolved in mountainous regions and flat towns, Haemi-eupseong is no exception in constructing fortresses on elevated ground for better observation and defense. Reinforcements were made in Hwangju, Dongnae, Jeonju, Daegu, and Haeju city. The case of Haemi-eupseong illustrates an applied and developed interpretation of both the traditional theory of township and the theory of strengthening towns that emerged after the two major invasions during the Joseon Dynasty. (Table 1)

Figure 7.

Planned City layout in Zhouli Kaogongji (Source: UNESCO World Heritage Centre) [

12].

Figure 7.

Planned City layout in Zhouli Kaogongji (Source: UNESCO World Heritage Centre) [

12].

Figure 8.

Symbolic authority expressed in the plan of the Hongju-mok area’s Walled towns (Source: Kim, H. 2014, 123) [

13].

Figure 8.

Symbolic authority expressed in the plan of the Hongju-mok area’s Walled towns (Source: Kim, H. 2014, 123) [

13].

Table 1.

Fortification Types and Features (Source: UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Namhansanseong, 178. Author restructured).

Table 1.

Fortification Types and Features (Source: UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Namhansanseong, 178. Author restructured).

| Standard |

Type |

Features of the fortification |

Haemi-eupseong |

| Type |

quadrilateral |

- |

|

| ancestor |

- |

|

| Semicircular |

- |

|

| oval |

- |

Oval shape with a developed square |

| Terrain |

Pyeongjiseong |

Installation of auxiliary facilities (ongseong, moat, wall, hostile, hamma pit), Joseon town |

○ |

| Pyeongsanseong |

Flat land + mountainous area, coastal or riverside construction, Hwaseong Fortress, Jindo Eupseong |

○ |

| Mountain fortress |

Temoisik |

Short Term: A wall that wraps around a flat mountaintop like a headband. |

|

| Pogoksik |

Long Term: A wall was built along the mountaintop surrounding the bowl-shaped basin terrain. |

|

| Samobongsik (Temoi + Pogok) |

Large-scale forms such as Capital |

|

| Function |

City |

Capital (Pyongyang, Gongju, Buyeo, Hanyang) |

|

| Eupseong |

Provincial administrative center, walled town, or non-walled town |

○ |

| Gungseong |

The fortified wall surrounding the palace |

|

| Haengjae-seong |

Temporary King's Residential Wall |

|

| Jangseong |

Linear fortress on the border |

|

| Special Functions |

Jinseong |

Small fortress stationed military Garrison |

○ |

| Dondae |

Detached observation tower |

|

| Boruseong |

Small-size border fort |

|

| Materials |

Mokchaekseong |

Palisade |

○

Jiseong (枳城) |

| Toseong |

soil |

|

| Seokseong |

stone |

|

| Toseokhonchukseong |

Soil + Stone |

○ |

| Jeonchukseong |

Brick, brick |

|

| Jeonseok Honchukseong |

Stone + brick |

|

| Wall Shape |

Dangwakseong |

One-line wall |

○

Daedongyeoji-do Map

Side two circularity analysis |

| Bokgwakseong |

Double-layered or multi-layered walls |

|

The connection between the town wall and nearby military facilities can significantly influence the interpretation of the heritage site's extended layout, reflecting the

flanking system's defensive strategy. The main entrance of Haemi-eupseong is Jinnammun Gate. This Jinnammun Gate is accessed by proceeding north along the stream that flows from Yangneungpo port on the Daedongyeoji-do map. Additionally, considering these major enemy access routes, two side facilities have been installed to effectively protect the walled town, the army, and the people. Furthermore, the Daedongyeoji-do map necessitates additional analysis (

Figure 9) of the two red circles to the right of Haemi-eupseong. Concerning Goryokaku (

Figure 10), located in Hokkaido, Japan, the front work of the West was constructed as a star-shaped pedestrian fortress with a moat, supplemented by an additional front work in the southeast. It is imperative to conduct further research to ascertain whether it functioned as a defensive outpost, forming a narrow system to defend against enemies approaching from land to the north, similar to frontwork or outpost, designed with the enemy's access through the port at the southern tip of Hokkaido in mind.

3.3.4. Uses and functions

As the damage to coastal areas increased due to frequent invasions by Japanese pirates during the late Goryeo and early Joseon Dynasties, many walled towns were constructed to defend coastal and inland settlements. However, following large-scale counterattacks against the Japanese pirates, their invasions nearly ceased around the 1420s, resulting in a diminished need for fortress walls. Furthermore, the two centuries from 1400 to 1592, characterized by the Japanese invasions, were a period of peace without significant upheaval. Consequently, the fortress assumed more symbolic importance than practical defense. The walled towns built after the 1420s were designed to resemble the Hanyang capital city wall as closely as possible, based on feng shui theory. In contrast, in areas where modifications or defences against Japanese pirates were deemed necessary, mountain fortresses were constructed instead, or the walled towns were reinforced. This approach is suggested to have been adopted following the relocation of the Chungcheong military commander's office to Haemihyeon County.

Most fortresses were constructed with symbolic significance during the Joseon Dynasty (14th – 20th centuries). Furthermore, fortresses were built focusing on defense following the Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592 and the Chinese Invasion of Korea in 1636. Until the mid-16th Century, the Joseon Dynasty emphasized the state's role in protecting the people more than military defense. After these two major invasions of the Joseon Dynasty, the city's defense system was enhanced, leading to the establishment of four Yusubu Special Magistrates to integrate military and administrative functions. In 1627, Ganghwa Yusubu was established to the West of Hanyang, followed by Gwangju Yusubu to the east of the Capital in 1683, Hwaseong Yusubu to the south of Hanyang in 1793, and Gaegyeong Yusubu to the north, all of which were actively utilized. Moreover, in 1711, the Bukhansanseong Mountain Fortress was completed, and in 1716, the Tangchundae Connecting Wall was established to strengthen the defense system in the north further. The introduction of this military-administrative integrated system was intended to reduce the burden on the people caused by the corruption and abuses of the regional-centered Jin-gwan defense system that strongholds (Jins) were established in each region to defend it and link up with the central army in times of emergency and had been in operation until the late Joseon Dynasty [

15]. The value of Haemi-eupseong can be found in Hoseo Regional Left Camp, which integrated the township's administrative functions and the military camp's military functions.

Suppose the analysis has centered on the Cheonsuman Bay area and the inland region of Haemi-eupseong. In that case, we shall examine the value of expanding the administrative function of Haemi-eupseong, focusing on the Pyeongsinjin (平薪鎭) Fort, which was established to protect the northwestern coast of Seosan County.

Since the foundation of the Joseon Dynasty, it has focused on implementing various policies for coastal defense. Moreover, the Seosan and Taean regions served as major transit points for transporting various goods, such as rice, and protecting food cargo vessels was the primary duty of the Pyeongsinjin Fort. The Cheomsa military official overseeing the Pyeongsinjin in the Seosan region also served as a Gammokgwan (監牧官) official and managed the ranch. It is suggested that he played a crucial role in the administrative and military aspects of the country's diplomacy, battles, dispatches, and communications, as he fulfilled significant duties in the horse administration of the Joseon Dynasty [

16]. In fact, on 11 February 1866 (the 3rd Year of King Gojong's reign), when the Rona ship, carrying the German merchant Oppert, secretly anchored in front of Jodo Island, Yeongjeon-ri village, Ido-myeon town, the Pyeongsin Cheomsa military official Kim Yeong-jun and Haemi County Magistrate Kim Eung-jip chased him away. This incident illustrates that this location held considerable strategic importance from the perspective of Joseon's outsiders.

3.3.5. Knowledge, Tradition, and Management System

It is a narrow analysis to describe the barrier and protective functions solely regarding the visible walls or moats. The surrounding mountains, rivers, and seas of Haemi-eupseong suggest a strategic incorporation of natural topography into its defense system, as indicated in Yeoji-do Map. Hence, during the establishment of Haemi-eupseong, there must have been diverse discussions regarding site selection. However, to understand the construction of Haemi-eupseong's walls, it is essential to investigate the historical context of the late Goryeo Dynasty and the early Joseon Dynasty and the construction methods employed for Ganghwaseong Fortress, Yongjangsanseong Fortress, and Donglimseong Fortress, which represent the Goryeo period, about societal changes.

Furthermore, the Hanyangdoseong Capital City Wall, a prominent fortification of the early Joseon Dynasty, symbolized a city wall and was constructed by mobilizing workforce from across the country, thus serving as a model for similar fortresses and walled towns. Additionally, Hanyangdoseong and Bukhansanseong Mountain Fortress and Tangchundaeseong Connecting Wall demonstrated ongoing advancements in fortress wall construction. In the process of strengthening the capital defense system after the two major wars of Joseon, such as the nearby Ganghwaseong Fortress, Hwaseong Fortress, and Namhansanseong, the tradition of fortification techniques was continued and applied and developed on-site.

Furthermore, additional facilities such as forts and fortresses were established to protect the fortress wall and main entrance. Creating a moat to restrict enemy access as much as possible possesses unique characteristics, as it is an element not commonly found in domestic fortresses (

Figure 11). The trifoliate orange tree, which is said to have been planted between the moat and the fortress wall, exhibits beauty when in full bloom. Simultaneously, it is an important element providing insight into the ancestors' foresight, as it serves a function akin to a wooden fence with deep roots (

Figure 12).

Haemi-eupseong is a flatland-walled town with a well-constructed fortress wall on the outside of the wall and a small stone and soil on the inside. Still, the hilly area is behind the Dongheon administrative center and the north gate where the Cheongheojeong pavilion is located. It is a mixture of flatland and hills, and the plain area continues so that one can look out over the west coast of the Korean Peninsula from Haemi-eupseong. On the stone of its outer wall, one can find the names of adjacent towns and villages such as Gongju, Cheongju, Chungju, Imcheon, Seocheon, Buyeo, and other towns and villages at the time of construction. It shows that Haemi County operated a kind of "real-name construction system" in which the section of the wall was divided into towns and villages so that the towns in that section would be responsible for repair if the wall collapsed such as, from the Jinnammun Gate to the right are Cheongju, Gongju, Lee ×, Hong, Gongju, Chungju, Chungju, Imcheon, Buyeo, Buyeo, Seocheon, Seocheon, Deokeun, Deokeun, Hongsan, Yeonsan, Hansan, Nisan, Nampo, Seokseong, Hoedeok, Hoedeok, Jinjam, Jinjam, ×in, Myeoncheon, Myeoncheon, Jeongsan, Jeon×, ×cheon, Boeun, Okcheon. Seosan Haemi-eupseong is owned by the country and managed by Seosan City. It was designated as Historic Site No. 116 on 21 January 1963 and was redesignated as a historic site on 19 November 2021 after the Korea Heritage Service revoked the cultural heritage designation number. Private houses and schools within the walled town were demolished to protect and manage cultural properties. Since 1970, annual renovation has been carried out on the city walls, gates, moats, and forts, which has continued to this day in 2011. Detailed excavations for the restoration of the original form have been conducted more than 10 times since 1980, and this has continued to this day. As such, with the interest and cooperation of the central and local governments, Seosan Haemi-eup town is continuously protected and managed.

3.3.6. Language and Intangible Cultural Heritage

Learning about the origins of the word ‘Haemi’ provides an excellent opportunity to explore regional identity. Haemi-hyeon County (海美縣) of Haemi-eupseong first appeared in historical records in the 7th Year of Taejong (1407). The following articles are regarded as significant evidence for describing the authenticity of Haemi-eupseong; thus, we will cite and analyze it as a feature that reflects the integrity of the World Heritage Site. It is referred to as the 'September fifth 1407 of the Annals of King Taejong' when quoted below.

The former Jeonghae-Hyun County (貞海縣) and Yeomi-Hyun County (餘美縣) were merged to become known as Haemi (海美), with Gammu Official being dispatched. At that time, the Uijeongbu State Council of Government reported the following based on the report of the Chungcheong Province Governor [

18].

Jeonghae County (貞海縣) and Yeomi County (餘美縣) were combined to form Haemi County (海美縣), and Gammu (監務) was placed again. Uijeongbu said,

According to the report by the Chungcheong Province Governor, although there are no residents in Jeonghae County, it is a vast uninhabited area under the Colonel (大嶺 Charyeong), where the three towns of Isan (伊山, Deoksan), Sunseong (蓴城, Taean), and Nampo (藍浦) are situated. Additionally, there is a strong stone fortress, and Mongung Station (夢熊驛), which belongs to the county, is the most critical location for receiving and sending visitors. In the event of unexpected rainfall, not only those in the area adjacent to Junghae-hyeon County but also the town residents of Gogu and Uncheon in Hongju County and Dongchon in Seoju County can enter the county to seek refuge. Hopefully, Jeonghae-Hyeon County will merge into Yeomi-Hyeon County, Gammu Official will be re-established, and finally, it will be called Haemi-Hyeon County.

Furthermore, through the connected ruins inside and outside Haemi-eupseong, we will find historical literature reflecting the deterrence of the Haemi-eupseong as a fortified structure and examine the language of authenticity alongside the aspects of intangible heritage. Firstly, in a poem titled Haemi Jeyeong (海美題詠) by Seo Geojeong (1420-1488), Haemi-eupseong is described as a majestic and enormous barracks, including a 'Military camp with strict military discipline,' 'The Great Wall of Military Commander,' and 'A Place Where the Flag Blows.' When faced with enemy invasion or imminent threat, the significance of this fortification plays a vital role in exerting psychological pressure. Otherwise, when Jeonghae County (貞海縣) and Yeomi County (餘美縣) were merged to create the name Haemi (海美), it can be seen that the geopolitical and geographical aspects were strongly interpreted. It can be inferred that functional factors such as politics, economy, society, culture, education, and religion related to the sea were at play. In this respect, Haemi-eupseong is also a significant place in the history of Catholicism in the Naepo region. It is one of the representative martyrdom shrines where more than 3,000 Catholics were executed at the end of the Joseon Dynasty. As a result, many Catholics visit Seosan Haemi-eup town every Year to engrave its meaning. An important case politically and diplomatically in connection with Haemi-eupseong is the objective facility of the Anheungjeong Pavilion. However, Anheungjeong can only be confirmed by records and ruins. In addition, the mountains surrounding Haemi-eupseong and the numerous Buddhist temples marked in it are valuable as a unique military cultural landscape and a good example of representing the Buddhist cultural landscape(

Figure 13). In particular, some of these temples have continued their functions and are inseparable from the regional functions of Haemi. Regarding geography, the local specialty emergency crops produced in Seosan continue the tradition of production based on good soil quality, strengthening the identity of local residents and playing a significant role in the local economy.

4. A Study on the Heritage Use and Reuse of Haemi-Eupseong Following the Theoretical and Methodological Approaches of ICOMOS Guidelines

The following is a theoretical and methodological application of the principles applicable to fortifications and military heritage specified in the ICOMOS Guidelines on Fortifications and Military Heritage to Haemi-eupseong. In particular, the seven objectives relevant to fortifications and military heritage and the corresponding methodologies are employed by Haemi-eupseong to analyze the current situation and propose directions for in-depth research related to conservation policies. Previous research on the authenticity of Haemi-eupseong provides direction for the utilization aspect including more systematic protection, interpretation, use, and reuse of the fortification heritage.

4.1. Historical Constructive Evolution, Stratigraphic and Spatial Complexity of the Structure

Objective: Preserve the multiple layers of stratigraphic, constructive, structural, and strategic information, the spatial relationship, and the elements that are part of contemporary territorial systems through the development of comprehensive preservation and maintenance guides specific to the needs of fortifications and their cultural landscapes [

20].

In the case of Haemi-eupseong, it is designated as a national heritage site, and the National Heritage Act stipulates that it should be preserved and managed by Seosan City, Chungcheongnam-do Province, the local government where the walled town is situated. The country supports and supervises the budget for its conservation and management. Seosan City periodically establishes a comprehensive maintenance plan for the sustainable conservation and management of Haemi-eupseong, systematically conducting conservation and management according to this plan. In particular, its value as a national heritage can be classified as historical and technical value. The results of in-depth research through excavation surveys reflect this value inside and outside Haemi-eupseong and are shared among the central government, local government, and research institutes involved in heritage conservation and management.

Furthermore, maintenance of internal facilities is being carried out to preserve the main components of the walled town, such as the fortress walls, military facilities, administrative buildings, and the surrounding environment. Notably, various efforts are being made to preserve the historical significance of Haemi-eupseong. When significant administrative and military functions at the regional and national levels, such as the Hoseo Regional Left Camp, existed, the status of the facilities was analyzed, and verification research was conducted through archaeological investigations and historical materials research. This process can potentially expand from the local and national levels to the East Asian level. It encompasses a study on town walls, particularly emphasizing the research regarding ‘town walls’ within the East Asian region. It offers an excellent opportunity to establish various international values by linking it with China and Japan's towns, walled towns, and fortresses.

4.2. External functional scope beyond its physical boundaries

Objective: To understand the fortification from the view of its operational zone.

As discussed in the authenticity section of Haemi-eupseong, the administrative role of Haemi-hyeon County in responding to the invasion of Japanese pirates during the Goryeo Dynasty, along with the joint operation of the Haemi County Governor and the Pyeongsinjin Fort military official to address the illegal ship anchorage and grave robbery incident involving the German merchant Oppert during the Joseon Dynasty, confirms the expansion of the military function of Haemi-eupseong and its actual operational aspects. To effectively conduct such military activities, a regular and efficient communication system between each military organization and an initial response system for enemy invasions must be established. For this purpose, the deployed troops and military facilities should not be viewed solely as the enclosed curved wall and internal administrative buildings that Haemi-eupseong currently resembles; instead, they should be analyzed with a multi-layered approach considering external factors. This research process can be understood as a military landscape comprising barrier and protection, command and control, depth, and flank defense rather than a single facility as perceived in the past. In other words, it should be regarded as a critical component of a cooperative system.

4.3. The lack of knowledge of the formal and functional characteristics of the fortification can be much greater than for other types of heritage structures

Objective: To promote excellence in the conservation of the historic fabric, archaeological remains, and the setting of a fortification and its cultural landscapes.

As aforementioned, archaeological investigations and authentic historical analysis in the Venice Charter must be conducted together to produce more reliable analytical results [

21]. These results can serve as tools to reinforce the site's historical value and local cultural identity. However, the Korean Principles [

22] also recommend that preserving the site's original state, along with minor repairs and maintenance, should be given top priority, rather than restoring and reconstructing the site based on speculation. Site managers are central to this conservation and research process, and their consistent conservation principles and interventions are considered crucial for sustainable conservation. It is significant that the Chungnam Research Institute of History and Culture, a public research institute of Chungnam Province, currently plays an important role in this process, continuously fulfilling its function. Through these individuals, in addition to the Seosan City public officials who are directly responsible for the conservation and management of Haemi-eupseong, joint research, and cooperation with nearby site officials connected to the historical functions of Haemi-eupseong continually provide opportunities for ensuring consistency in an expanded dimension.

4.4. Fortifications and Communities

Objective: To develop an appropriate interpretation with emphasis on facilitating the creation of an accurate history and relationship to the changing cultural, social, and political contexts, including the relationships between contemporary elements and their effectiveness in territorial protection;

To reinforce visitors and local community appreciation of the site through interpretation of transnational values as a common heritage;

To reinforce visitors and local community appreciation of the site by developing effective tools that foster an agreed and consensual interpretation of identity values;

To reinforce visitors and local community appreciation of the site by developing effective tools that foster a comprehensive and consensual interpretation of identity values, in order to encourage a people-centered, rights-based approach and integration of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) to identification, interpretation, access and management policy.

The ICOMOS Guidelines state that fortresses play a vital role in the cultural identity and traditions of communities, nations, and regions. Furthermore, care must be taken not to promote acts that highlight or exclude specific values when interpreting sensitive issues. Meanwhile, Haemi-eupseong is deeply connected to the history of Korean Christianity. Missionaries who arrived in Korea in the late Joseon Dynasty to spread Christianity and believers who had already embraced the faith faced open persecution from state policy. Haemi-eupseong is at the center of this persecution, with various historical materials confirming the existence of public information facilities installed within the prison area of the fortress, clearly visible to the naked eye.

Additionally, the nearby Haemi Catholic Martyrs Memorial Hall systematically exhibits and educates visitors about the history of the religious influx and scenes of persecution, ensuring that religious groups, students, and interested tour groups continue to visit and appreciate the historical significance. On the other hand, Haemi-eupseong is interpreted as a Buddhist cultural landscape that shares the history and context of the Buddhist temple facilities established on several mountains, including Gayasan Mountain, which lies at the end of the Charyeong Mountain Range in the northeast, owing to its geographical advantages. They also form a Buddhist community, visiting Haemi-eupseong through yearly events to commemorate their interconnected past. In this respect, it is unacceptable for any specific religious group to monopolize or interpret Haemi-eupseong; instead, the interconnected value of the relics should be continually discovered and shared in a refined manner from diverse perspectives.

4.5. Fortifications use and reuse

Objective: To promote interventions on fortifications and military heritage only where the purpose is to provide sustainable and appropriate reuse;

To establish a balanced reuse to avoid destroying integrity and authenticity;

To promote reuse that transforms fortifications and military heritage into a place of witness and aggregation of communities;

To promote reuse that transforms fortifications and military heritage into places of knowledge such as places for interpreting military heritage including topics such as history, science, technology, etc.; To promote reuse that transforms fortifications and military heritage into places which transmit a message of inclusiveness, and reconciliation.

The ICOMOS Guidelines recommend that, due to the evolving nature of military operations, fortifications are often not reusable for their original specific construction purposes. It is challenging to ensure accessibility and meet the requirements for current use, as the fortress walls have become difficult to enter. In the case of Haemi-eupseong, although its historical function has vanished, its military role has expanded to nearby areas on a regional level. In particular, during the Korean War (1950-1953), regarded as a modern conflict in Korean history, the logistics function to respond to the communist camp appears to have broadened from a national to an ideological camp level. The US military airport, which is the most extensive air force base in South Korea and the most significant air force in East Asia near Haemi-eupseong, established to address emergencies, signifies a development that extended Haemi-eupseong's function during the Joseon Dynasty, which comprised the Army and Navy, facilitating joint operations by the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Allied Forces of the UN.

On the other hand, although the past function of the relics has disappeared, certain hazardous areas and the interiors of the buildings are restricted to ensure the safety of visitors and preservation. Given that the facilities within Haemi-eupseong consist of wooden structures, the conservation authorities strictly prohibit activities such as lighting fires and smoking, even though events are permitted. Over time, and due to natural disasters, components of the relics are falling off, corroding, and sustaining damage. To this end, detailed records of the relics are being meticulously maintained, and authorized institutions are restoring the original forms. All heritage-related processes are disclosed to visitors and stakeholders through various means, both online and offline, to seek their understanding.

4.6. Fortification and urban landscape and territorial dimensions

Objective: To foster greater awareness of the need to understand and interpret fortifications and military heritage as a component of international or transnational systems, territories, and settlements of urban ensembles and not as solitary and isolated structures.

The ICOMOS Guidelines state that the purpose is to clarify the need for a better conservation strategy for urban heritage, expressed as a defense system, a single element, or an entire network, within the comprehensive and sustainable development goals that support public and private measures to protect and enhance the quality of the human environment. As explained above, the central government is the principal entity responsible for the conservation and management of Haemi-eupseong, as it is designated as a national heritage site. The central government delegates the conservation and management of the site to the local government, which is established through the National Heritage Act, and formalizes budgetary support for this. Accordingly, the relevant local governments, Chungcheongnam-do Province, and Seosan City cooperate to conserve and manage the site. At the same time, the Chungnam Institute of History, a public research institute of Chungnam Province, is tasked with academic research and field investigations for this purpose. In addition, it opens a route for relevant organizations, scholars, and researchers in the region with expertise in research and field investigations to officially participate, encouraging a holistic, multidisciplinary, and multi-layered approach to the conservation and management of the site. All activities are monitored and implemented to ensure sustainability through the mid-to-long-term comprehensive development plan for Haemi-eupseong established by the local government.

4.7. Fortifications are not typical buildings

Objective: To improve methodological tools for research and multidisciplinary understanding.

The ICOMOS Guidelines state that fortifications can vary from a single structure to a complex multi-structure defense system developed over a long period. However, there may be a lack of comprehensive understanding of the site that identifies the significant stages of development, which cannot be distinguished solely by the diversity of structures and the interconnectivity of all the important physical elements of the site (i.e., structures, cultural landscapes, views, etc.). An analysis of the administrative-military functions of Haemi-eupseong reveals that a crucial aspect of the Korean Peninsula was the management of transportation during the Joseon Dynasty. Rice, used as food, tax, and barter for the people during the Joseon Dynasty, was grown and harvested in the southern region of the Korean Peninsula and transported to the capital city of Hanyang via coastal routes. Anheungjin Fort, near Haemi-eupseong, was where shipping cargo vessels anchored. Since this site was on a treacherous sea route, many ships were wrecked by strong waves or typhoons in the summer. The Joseon Dynasty government considered this and developed a canal linking Cheonsuman Bay and Gyeongin Bay, known as the Gulpo Canal. However, although the safety of the cargo was secured, construction faced delays due to the rocky terrain along the canal's route. Consequently, it could not be transported at once by tax carriers, necessitating double or triple the labor to unload the cargo, load it onto carts, transport it by land, and then reload it onto cargo vessels for transport once again. Haemi-eupseong managed this transportation system and is overseen by Taean County, an adjacent local government. While administrative management centered on local governments in Korea ensures fairness and efficiency in regional governance, instances arise when it struggles to overcome regional egotism concerning heritage. As a significant linked heritage associated with Haemi-eupseong, the Gulpo Canal is not receiving proper attention for its value. Therefore, research, interpretation, and integrated conservation management through wide-area cooperation on historical heritage are necessary for fortress heritage such as Haemi-eupseong.

5. Conclusion

Concerning Haemi-eupseong, we have investigated the authenticity criteria specified in the Operational Guidelines of World Heritage to determine heritage value. These criteria encompass location and setting, form and design, materials and substance, use and function, traditions, techniques, management systems, language, and various forms of intangible heritage. Additionally, we have assessed the theoretical and methodological aims of the ICOMOS Guidelines on Fortifications and Military Heritage, which lay out crucial criteria for appreciating fortification heritage, especially considering Haemi-eupseong's designation as such. This assessment includes the historical evolution of the construction, the stratigraphic and spatial intricacies, its functional extent beyond mere physical boundaries, and the fact that the ignorance surrounding the formal and functional aspects of fortifications often exceeds that of other heritage structures. Furthermore, we examine the relationship between fortifications and communities, their usage and re-usage, and their ties to urban landscapes and territorial dimensions, highlighting the significant differences that set fortifications apart from standard buildings. Through this examination, we have systematically applied international standards to the elements related to Korea, thereby organizing their value and significance more objectively. Moreover, with further comprehensive research, it may be feasible to establish heritage value at a wider level, linking it to related heritage beyond the local context, and we have explored methodologies that could enhance the dissemination of value through interpretation and conservation management.

In particular, it was found that the authenticity of Haemi-eupseong and the complexity and rich stratification of the fortification heritage require proper management, interpretation, and protection at an integrated landscape level rather than viewing it as a single relic. Furthermore, to implement this, understanding and cooperation with various stakeholders, including local government officials at the forefront of Haemi-eupseong conservation and management, should be encouraged.

It was also determined that various historical materials and heritage-related collections reflecting authenticity, archaeological research, and excavation surveys should not be conducted separately from efforts to preserve architectural structures and designs. Instead, they should be integrated organically to facilitate the sustainable protection of Haemi-eupseong. Additionally, recognizing that Haemi-eupseong is a fortification heritage site, the combination of spatial elements connected to its historical military functions is closely related to the surrounding setting. This includes the prevailing views for defense and attack functions, as well as the designated security areas necessary for maintaining military operations, all of which can be interpreted as significant components of a military cultural landscape.

In understanding, establishing, interpreting, and protecting these values, education and capacity building for the on-site managers and relevant stakeholders regarding the heritage should be undertaken. In particular, through this process, specialized knowledge of the fortifications' characteristics can be enhanced and developed, leading to appropriate scientific conservation measures and the creation of a mid-to-long-term maintenance plan for its implementation.

Regarding the use and application of Haemi-eupseong's heritage, the prison located within the eupseong, which was used during the period of Christian persecution in the late 19th century, has been re-excavated to serve as historical content. The interpretations suggest that Christianity spread through this process and can positively influence future reuse directions tied to Haemi-eupseong's past military and administrative functions. Beyond being a site of incidents related to Christian persecution, ongoing interpretations and refined information sharing about other religious traces and histories can further diversify awareness of identity and communication concerning Haemi-eupseong in the future. These actions must be connected to guidelines, policies, and implementation strategies regarding heritage tourism within the mid-to-long-term comprehensive maintenance plan. Accessibility to heritage should be systematically addressed in this plan. When visitors cannot enter due to maintenance of the heritage site, alternative information or accessibility options must be adequately considered. Moreover, if information or on-site disclosures regarding various heritage conservation measures are officially made through state-registered procedures, it could foster trust with visitors. In Korea, the primary entities responsible for conserving and managing designated cultural heritage sites, including world heritage sites, are local authorities, metropolitan governments, and the central government. Since this is funded by citizens' taxes, they can be considered primary visitors. The on-site disclosure of permitted, refined, and systematic heritage conservation measures can build trust with visitors, enabling them to appreciate the local and regional value of the heritage and its expanded linkage significance. Arranging meetings with stakeholders and applying these insights to heritage conservation, interpretation, and recycling will greatly benefit sustainable heritage conservation management.

References

- Korea Heritage Digital Service, Haemieupseong Walled Town, Seosan. Available online https://digital.khs.go.kr/record/recordDetail3D.do?ichDataUid=13903604969116200662&bizId=BIZ201600002466&ctptCeCdList=%EC%A0%84%EC%B2%B4&adresSeCdList=%EC%A0%84%EC%B2%B4&pageSe=all&searchText=%25EC%2584%259C%25EC%2582%25B0%2520%25ED%2595%25B4%25EB%25AF%25B8%25EC%259D%258D%25EC%2584%25B1 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Korea Heritage Service. In-depth Study on Establishing Principles for Preservation of Cultural Properties, 2022, 16-17. Available online: https://www.heritage.go.kr/heri/cul/linkSelectEbookDetail.do?pageNo=1_3_0_0&bbsId=BBSMSTR_1021&nttId=85376 (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS Guidelines on Fortifications and Military Heritage (2021). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters-and-doctrinal-texts/ (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- Kim, M. Review of Ahn Heung-jeong in the Goryeo Period, Yeongnam Studies, 2019, No. 70, 180.

- Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies of Seoul National University, Daedongyeojido Map, Available online: http://kyudb.snu.ac.kr/pf01/rendererImg.do?item_cd=GZD&book_cd=GK10333_00&vol_no=9999&page_no=&imgFileNm=&tbl_conts_seq=&mokNm=&add_page_no= (accessed on 09 June 2025).

- Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies of Seoul National University, Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, Sinjeung dongguk Yeoji Seungram, Haemi-Eupji. Available online: https://kyudb.snu.ac.kr/book/view.do?book_cd=GK17388_00 (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- The Academy of Korean Studies, The Korean Local Culture Encyclopedia, Seosan six-piece garlic (Seosan Yukjjok maneul). Available online: https://www.grandculture.net/seosan/ (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- Institute of Military History of the Ministry of National Defense. Military Strategy of the Goryeo Dynasty. Samhan Information Plan, Seoul, Korea, 2006. Available online: https://www.imhc.mil.kr/user/indexSub.action?codyMenuSeq=70543&siteId=imhc&menuUIType=sub (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- GoogleMaps. Haemi-eupseong. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Haemi+Eupseong+Fortress/data=!3m1!1e3!4m6!3m5!1s0x357a5e238d9a41ef:0x136ed2233511d869!8m2!3d36.7125761!4d126.5486189!16s%2Fm%2F04q3235?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDYxMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Namhansanseong. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1439/documents/ 145, 194 (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- Kim, H. A Study on the Characteristics of the Urban composition of provincial city ‘Eupchi(邑治)’ of the Hongju-mok(洪州牧) region in the Late Joseon(朝鮮) Dynasty. Ph.D. Thesis, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Korea, 2014, 25–27, 138.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Namhansanseong. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1439/documents/ 145, 194 (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- Kim, H. A Study on the Characteristics of the Urban composition of provincial city ‘Eupchi(邑治)’ of the Hongju-mok(洪州牧) region in the Late Joseon(朝鮮) Dynasty. Ph.D. Thesis, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Korea, 2014, 123.

- Google Earth. Goryokaku. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/search/Goryokaku/@41.79669983,140.75835419,11.49431205a,2086.12523302d,35y,-0h,0t,0r/data=CngaShJECiUweDVmOWVmNDZiY2I4ZDU1MjU6MHhhOWU0YmQyZDk2YzRkNTAyGclwPJ8B5kRAIZDkqJI3mGFAKglHb3J5b2tha3UYAiABIiYKJAlTglw_uGczQBFQglw_uGczwBlkCy29V89IQCE1tr54MmpJwEICCAE6AwoBMEICCABKDQj___________8BEAA (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Ministry of National Defence, Military History Institute, Military Strategy in Joseon Dynasty, 2006, 186.

- Nam, D. Korean Horse Administration History, Studies Series No. 1 of the Equine Culture, The Equine Museum of Korea Racing Authority; Samyoungmunhwa, Gwacheon, Korea, 1996. 215–236.

- Korea Heritage Service, Natural Monument No. 78, Gapgot-ri village, Ganghwa County, trifoliate orange tree. Available online: https://www.heritage.go.kr/heri/cul/culSelectDetail.do?pageNo=1_1_1_1&sngl=Y&ccbaCpno=1362300780000 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Lim, S. The Construction and Functional Change of Haemi-eupseong in the Joseon Dynasty-Hoseo at Chungcheong Barracks, History and Discourse, Vol. 58, 2011, 75-76.

- Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies of Seoul National University, Haemihyeon-do, Yeoji-do. Available online: http://kyudb.snu.ac.kr/pf01/rendererImg.do?item_cd=GZD&book_cd=GR33496_00&vol_no=0000&page_no=&imgFileNm=GM33496IL0002_107.jpg&tbl_conts_seq=&mokNm=&add_page_no=.

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS Guidelines on Fortifications and Military Heritage (2021). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters-and-doctrinal-texts/ Art. 3 Theoretical and methodological (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (Venice Charter, 1964). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/venice_e.pdf (accessed on 08 June 2025).

- Korea Heritage Service. Korean Principles for conserving values of Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://www.khs.go.kr/newsBbz/selectNewsBbzView.do?newsItemId=155705378§ionId=b_sec_1&mn=NS_01_02 (accessed on 08 June 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).