Abstract Background/Objectives: Regional differences in genomic mutation profiles of uterine cervical cancer have been reported. Japanese people are divided into two genetic background clusters, originating from mainland Japan and Okinawa. No studies have examined gene mutation profiles of cervical cancer in Okinawa. This study aimed to investigate the mutation profile of cervical cancer in Okinawa in addition to predictive genetic mutations for prognosis after definitive radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Methods: Twenty-three patients with biopsy-proven squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the intact uterine cervix who were treated with definitive radiotherapy were analyzed. Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh frozen tissue samples collected by tumor biopsy prior to treatment. Variants of 224 cancer-related genes were identified using next-generation sequencing. Genetic mutations were identified and their associations with clinical outcomes were examined. Results: A total of 29 gene mutations were observed in 16 patients, including nine recurrent mutations: SCN7A (17%), PIK3CA (13%), FGFR4 (13%), USP6 (13%), SETD2 (9%), KIT (9%), TSC1 (9%), SERPING1 (9%), and NOTCH3 (9%). Significant mutations in ARID1A, FBXW7, PTEN, TP53, and EP300, reported as relatively common in cervical cancer in other regions were not detected. The rate of 2-year overall survival and progression-free survival was 95.5% and 73.4%, respectively. No significant differences were observed between gene mutations and either survival. Conclusions: The findings indicate that the gene mutation profiles of cervical cancer in Okinawa may differ from those in other regions. Genetic mutations were not identified as significant prognostic factors after definitive radiotherapy.

1. Introduction

Uterine cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women globally, with approximately 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths annually [

1]. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) is the standard of care for patients with advanced disease [

2], but the treatment outcomes remain poor. Cervical cancer has a significant impact on society because it disproportionately affects young women. Among children who lose their mothers to cancer, cervical cancer accounts for 20% of maternal deaths [

3].

In recent years, genome-based cancer precision medicine with next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has been applied across various cancers [

4]. In the past decade, the genetic landscape of cervical cancer has been described [

5,

6]. Many subsequent reports have documented genetic mutations that affect prognosis, including

FGFR [

7],

KRAS [

8,

9,

10],

PIK3CA [

10,

11,

12,

13],

ERBB2 [

10,

14], and

MLL2 [

10], although precision medicine is not yet the standard treatment for cervical cancer.

Comparing reports from different regions indicates regional differences in genomic mutation profiles in cervical cancer [

6,

7,

8,

15]. Genetic profiling of cervical cancer has also been reported in patients from mainland Japan [

7]. Japanese people are divided into two genetic background clusters originating from mainland Japan and Okinawa [

16]. Therefore, mutation profiling of cervical cancer in Okinawa may differ from the profile reported in mainland Japan.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the mutation profile of cervical cancer in Okinawa through comprehensive somatic gene mutation analysis using NGS. The goal was to contribute to the advancement of personalized treatment for cervical cancer. Additionally, this study aimed to identify genetic mutations that are predictive of prognosis after definitive radiotherapy (RT) for cervical cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Eligibility Criteria

This single-center, prospective, observational study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of the Ryukyus (approval number: 1649). The study adhered to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. All patients signed informed consent forms before enrollment and sample collection.

Eligible patients had biopsy-proven squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or adenocarcinoma (AC) of the intact uterine cervix, and were treated with definitive RT alone or CCRT between September 2020 and June 2022 at the University of Ryukyus Hospital. Additional eligibility criteria were 2018 Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB2–IVA, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) 0–2, ≥ 20-years-of-age, and no history of RT for the pelvic region.

2.2. DNA Samples and Targeted Sequencing

Tumor tissue was obtained from all patients prior to cancer treatment by punch biopsy or a curette when punch biopsy was difficult. The samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained specimens were prepared from all frozen samples. One of the authors who is a specialized pathologist (K. K.) confirmed that the tumor components were identified in all specimens. Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh frozen tissue samples using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany).

Targeted NGS of genomic DNA samples was performed using the SureSelect Customs DNA Target Enrichment Probe (Agilent Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA) and the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). SureCall software ver.4.2 (Agilent Technologies) was used to identify the variants. The probe was designed for 224 cancer-related genes (

Figure S1) that are genetic mutations included in cancer panel tests or mutations that have been potentially associated with cervical cancer [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Variants were filtered out by the following exclusion criteria: (1) synonymous mutations and variants in introns, except for splice sites and a promoter region (TERT), (2) variants with ≥ 1% allele frequency in online single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) databases, and (3) variants not listed in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (

https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic). Additionally, variants considered likely to be benign were excluded based on the Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant score, dbSNP database, or correlation between the tumor proportion in the tissue samples and variant allele frequency.

2.3. Follow-Up Evaluations

Follow-up evaluations were typically performed at three-month intervals. The evaluations included gynecological examinations, tumor marker tests, histological or cytological confirmation, and imaging. Oncological event times were measured from the start of RT. Local failure was defined as recurrence or persistent disease in the cervix, uterine corpus, parametria, or vagina. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the absence of disease or death from any cause. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the absence of death due to any cause. Patients without adverse events were censored at the time of their final follow-up evaluation. Late adverse events were evaluated using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean values between two groups. Time-to-event analyses were conducted using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the association between events and genomic mutations. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR ver. 1.41 (Saitama Medical Centre, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), and a graphical user interface for R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients, Tumors, and Treatments

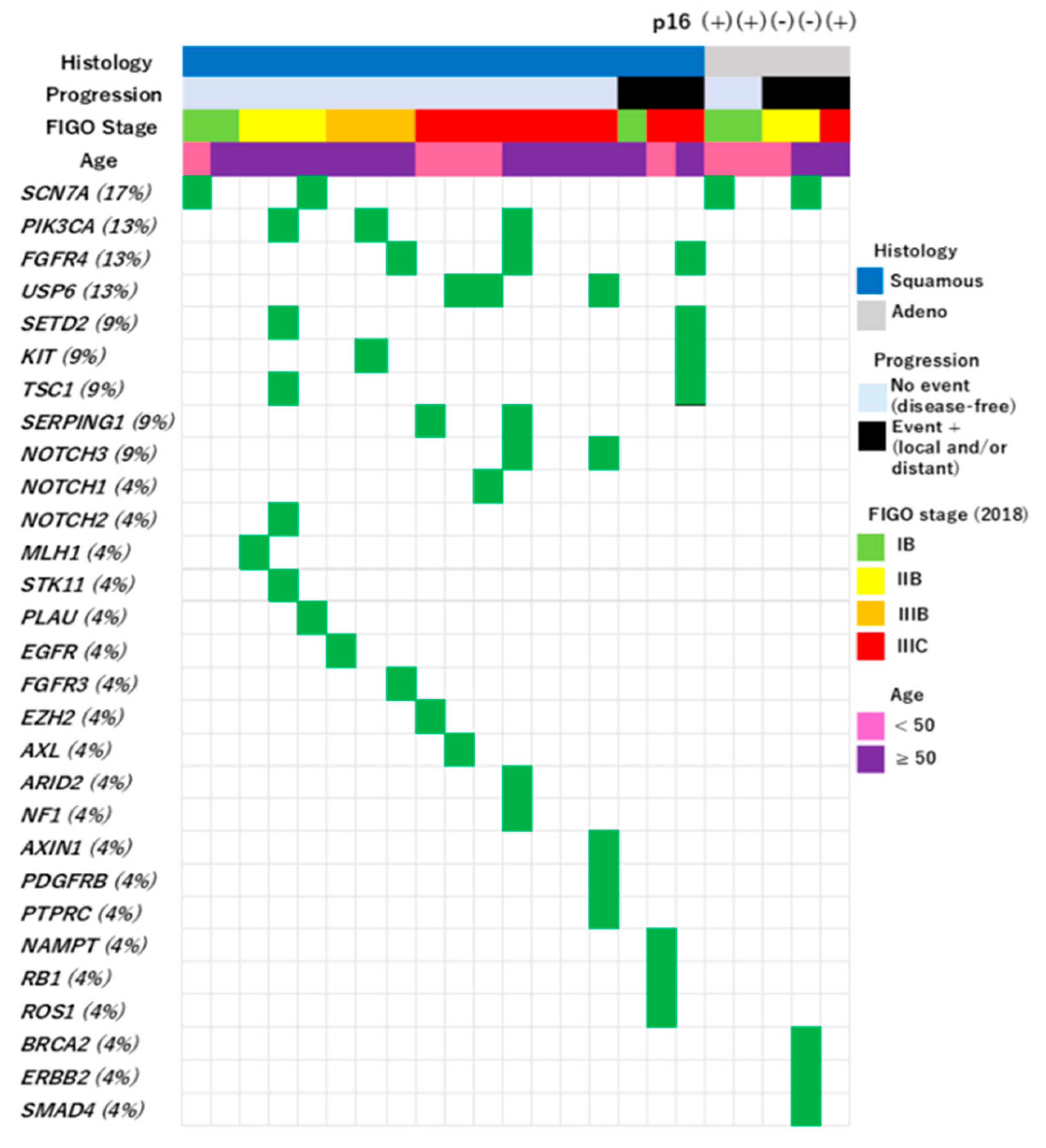

A total of 23 patients were enrolled (

Table 1). Eighteen cases of SCC (78%) and five cases of AC (22%) were included. Staining for p16 was performed in all five cases of AC and was positive in three cases and negative in two cases. For SCC, p16 staining was performed in only two of 18 cases, and both cases were positive.

The details of the treatments are shown in

Table 2. CCRT was administered to 21 patients and RT alone to two patients ≥75-years-of-age. RT consisted of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) and three-dimensional-image-guided brachytherapy (3D-IGBT). EBRT was delivered with a 10 MV photon beam using a linear accelerator (Clinac iX, Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The EBRT fields included the whole pelvis (n = 20), small pelvis (n = 2), and extended field, including para-aortic node (n = 1). Small pelvic irradiation was performed in two elderly patients who were the same as those who were treated without chemotherapy. The upper edge of the extended irradiation field was set to the upper edge of the L1 vertebral body.

The prescribed EBRT dose was 50 Gy in 25 fractions with central shielding after 40 Gy. An initial dose of 40 Gy in 20 fractions was delivered using a four-field technique, and a subsequent dose of 10 Gy in five fractions was delivered using an anterior-posterior field with a 4 cm-wide central shield. Additional radiation of 6 Gy in three fractions was administered to the parametrial tissue in T3b cases and/or lymph node metastases. All patients were treated with three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy and no intensity-modulated radiation therapy was administered.

3D-IGBT was delivered using a high-dose-rate 192Ir remote afterloading system (MicroSelectron, Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden). IGBT was planned based on computed tomography (CT) images with a 1.25 mm slice thickness, with applicators inserted. Three brachytherapy sessions were performed. All patients received intracavitary irradiation alone without interstitial irradiation. The dose regimen was optimized considering the dose to the tumor and surrounding organs at risk. The high-risk clinical target volume (HR-CTV) was contoured according to Japanese Radiation Oncology Study Group (JROSG). The cumulative doses from EBRT and 3D-IGBT were calculated by a simple summation in the biological equivalent dose 2 Gy per fraction (EQD2) using the linear-quadratic model with an α/β of 10 Gy for tumors and 3 Gy for organs at risk. The median cumulative dose for HR-CTV D90 was 71.5 Gy (range, 60.7–82.1 Gy), bladder D2cm3 was 65.0 Gy (58.0–79.2 Gy), rectum D2cm3 was 59.2 Gy (44.8–73.4 Gy), and small bowel D2cm3 was 51.8 Gy (43.9–63.6 Gy).

Weekly cisplatin (40 mg/m2) was the standard chemotherapy regimen, which could be skipped due to the patient's condition. A median of five courses (range, 3–6 courses) was administered. A triweekly paclitaxel and cisplatin regimen (paclitaxel, 50 mg/m2, days 1, 8, and 15; cisplatin, 50 mg/m2, day 1) was administered to six patients: five with adenocarcinoma histology and one with SCC with para-aortic node positivity.

3.2. Somatic Mutations in 224 Cancer-Related Genes in Okinawa Cervical Cancer Cases

No genetic mutations remained after filtering in seven cases. One or more genetic mutations were observed in the remaining 16 cases (

Figure 1). The details of filtering are described in the Materials and Methods section. The following mutations were manually omitted after systematic filtering:

BRCA2 (M784V),

PARN (G520R),

UQURC (D215H),

NOTCH2 (I1689F),

RET (D235N),

HLA-DQA (F238L), and

NOTCH1 (R1279H).

A total of 29 gene mutations were observed in 16 patients (

Figure 1). These included nine recurrent mutations:

SCN7A (17%),

PIK3CA (13%),

FGFR4 (13%),

USP6 (13%),

SETD2 (9%),

KIT (9%),

TSC1 (9%),

SERPING1 (9%), and

NOTCH3 (9%). The most common mutation was

SCN7A, which was detected in four cases, followed by L1357F (n = 3) and I605M (n = 1).

All samples, including seven cases without significant mutations, were confirmed to contain tumor tissue by the specialized pathologist. There was no significant difference in the proportion of tumor components in the specimens between the 16 cases with gene mutations (mean = 57.5%, standard deviation = 21.2%) and the remaining seven cases (mean= 42.9%, standard deviation = 26.3%) (p = 0.17).

No genes showed significant differences in mutation frequency between the SCC and AC histological types.

3.3. Comparison of Genetic Mutation Profiles Between Patients in Okinawa, Mainland Japan, China, and Western Countries

Genes with mutations reported at a frequency ≥ 10% in the current study or reports from other regions [

6,

7,

15,

23,

24] were compared (

Table 3). The most frequently detected mutation in the current study was

SCN7A (17%), although no other reports mentioned the frequency of

SCN7A mutations in cervical cancer.

PIK3CA mutations, which have been reported frequently in other regions (17–40%), were detected in 13% of the patients in the current study.

Comparing this study with a report from mainland Japan [

7], the frequency of

FGFR4 mutations was similar (13% in Okinawa and 11% in mainland Japan).

FGFR3 and

NOTCH1 mutations were relatively frequent in mainland Japan (21% and 19%, respectively) but only 4% each in Okinawa. In several reports from other regions,

FBXW7 (11–19%),

ARID1A (7–26%),

PTEN (4–10%),

TP53 (7–16%), and

EP300 (6–12%) mutations were found at relatively high frequencies in cervical cancer, but were not detected in the current study.

3.4. Clinical Outcomes

Except for one patient who was lost to follow-up at 14 months, all patients were followed up for at least 24 months from the start of treatment. The median follow-up period was 32 months (range,14–40 months). Two deaths and six recurrences (local only, n = 2; distant only, n = 2; local and distant, n = 2) were observed during the follow-up period. Genetic mutations were not significantly associated with tumor recurrence.

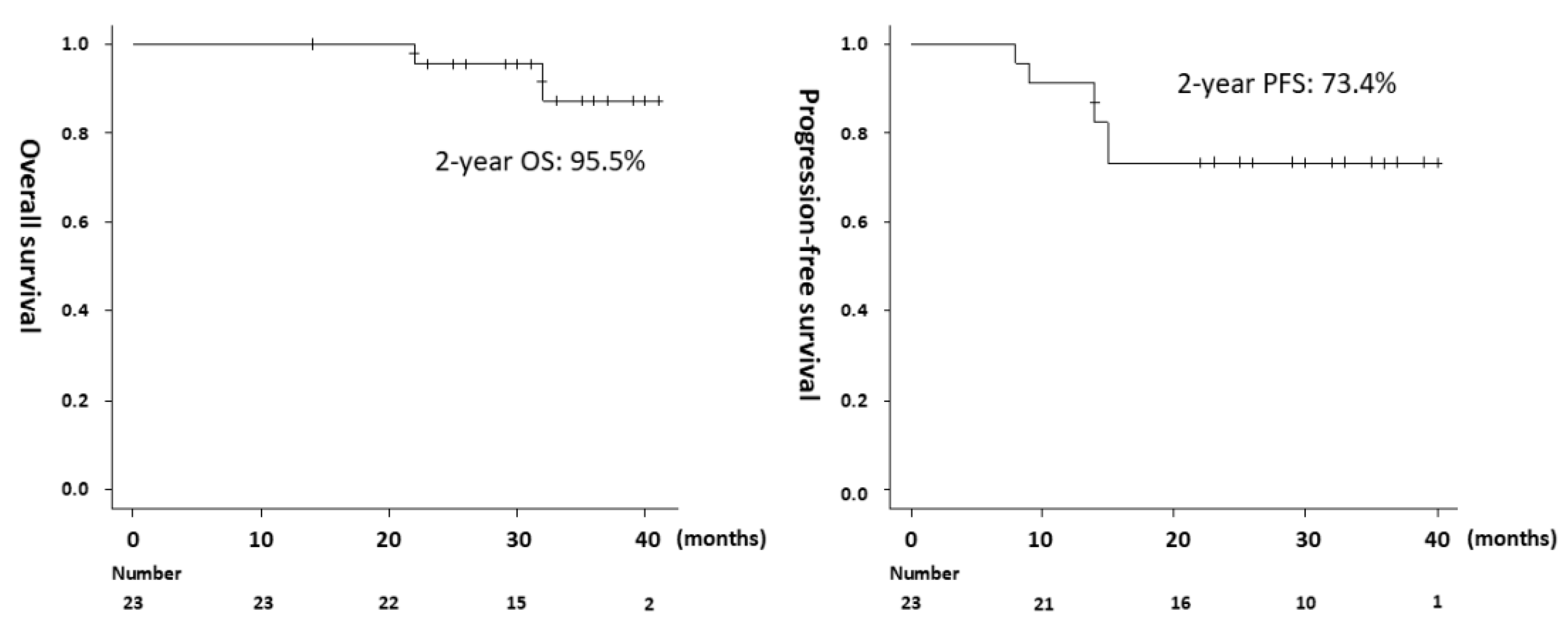

The 2-year OS for all 23 patients was 95.5%, 2-year PFS was 73.4% (

Figure 2), and 2-year local control (LC) was 82.0%. The pathology of the two deceased patients was AC, and none of the 18 patients with SCC died during the observation period. The OS was significantly shorter in the AC group than in the SCC group (median, 32 months vs. not reached, p = 0.0003). Recurrence was observed in three of five patients with AC and in three of 18 patients with SCC, and PFS was significantly shorter in the AC group (median, 14 months vs. not reached, p = 0.016). Regarding lymph node status before treatment, recurrence occurred in 3 of 10 positive and 3 of 13 negative cases, with no significant difference in PFS (p = 0.669). Late adverse events of CTCAE Grade ≥ 2 were gastrointestinal (9%), urinary (4%), and pelvic bone fracture (4%).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the genetic profile of cervical cancer in Okinawa. The findings suggest that the profile may differ from the profiles in other regions, including mainland Japan. Some genetic mutations reported to be relatively common in cervical cancer in other regions were not detected in the present study.

Previous reports have suggested that the frequencies of gene mutations that can be targeted by small-molecule drugs are low in cervical cancer. As a small-molecule targeted drug for recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer, selpercatinib is considered useful for

RET fusion-positive tumors, and larotrectinib/entrectinib is considered useful for NTRK fusion-positive tumors [

25]. However, it is obvious from previous reports that these gene mutations are rare. Consistent with previous reports, the present study did not identify any mutations that could be targets of small-molecule drugs.

PIK3CA,

ARID1A,

FBXW7,

PTEN, and

TP53 mutations have been reported relatively frequently in cervical cancer from other regions, and are considered attractive targets for novel molecular-targeted drugs [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], which are expected to lead to improved treatment outcomes. However, the current study suggests that mutations in genes other than

PIK3CA are rare in Okinawa. Therefore, establishing unique treatment strategies for cervical cancer is essential in this region.

SCN7A mutations were the most frequently detected.

SCN7A belongs to the

SCN family, which plays a vital role in several pathophysiological processes of tumors by manipulating, cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [

31].

SCN7A is one of the key genes associated with colorectal cancer, and mutations in

SCN7A worsen the prognosis of colorectal cancer [

32]. In recent years,

SCN7A has attracted attention as a new biomarker of cancers, including gastric cancer [

33], esophageal cancer [

34], lung cancer [

35], and hepatocellular carcinoma [

31]. However, no studies have reported the frequent detection of

SCN7A mutations in cervical cancer, and the association between

SCN7A mutations and prognosis has not been addressed. In the current study, the impact of

SCN7A mutation on the prognosis of cervical cancer after definitive RT was not clarified. Furthermore, the actual differences in

SCN7A mutations according to histopathological type remain unclear owing to the modest cohort size, although

SCN7A mutations were detected in both SCC and AC without significant differences in the current study.

The frequency of

USP6 mutations in cervical cancer has not been reported in studies performed in other regions.

USP6 mutations were found in 13% of cases in the current study.

USP6 encodes a deubiquitinating enzyme that plays critical roles in diverse cellular processes. Recent studies have demonstrated that

USP6 promotes tumorigenesis through multiple pathways, including the Wnt, JAK1-STAT3, and c-Jun pathways [

36,

37].

USP6 activity has been reported to be associated with the development of Ewing sarcoma [

38], but the clinical impact of

USP6 mutations on cervical cancer remains unknown.

In terms of treatment outcome, the 2-year LC of 82%, which was 10% lower than the 5-year LC of 92% reported in a global large-scale prospective observational study [

39]. The reason for the lower LC rate may be the difference in cumulative target dose, which was a median of 90 Gy (EQD2, α/β=10 Gy) in the prior study and 71.5 Gy in the current study. The reason for the lower target dose in the current study than in the prior study may be that the interstitial brachytherapy was not performed, and CT was used instead of magnetic resonance imaging as the imaging modality. Additionally, as shown in

Table 1, there may have been more slim patients in this study than the global standard. The small intestine tends to be located close to the uterus in slim patients [

40]. Thus, the prescribed radiation dose must be reduced to avoid high-dose exposure to the small intestine. No significant gene mutations were identified as prognostic factors in the current study, likely because of the small sample size.

Modest cohort size is the main limitation of this study. In addition, this study was performed at a single institution, although this is uncontrollable given that our institution is the only one in Okinawa that offers definitive RT for cervical cancer. Only cases planned for definitive RT were included in the study; patients with FIGO stages IA and IV were excluded. Only gene mutations in tumor tissues were analyzed. It was unclear whether all patients had their genetic origins in Okinawa, and patients who lived in Okinawa but were not genetically of Okinawan origin might have been included. Mutations that seemed to be benign were excluded by referring to online databases and/or by comparing the tumor proportion in collected tissues with variant allele frequencies; however, the results may not be completely accurate.

5. Conclusions

NGS revealed that the genetic profile of cervical cancer may be unique in Okinawa. No genetic mutations were identified as significant prognostic factors after definitive RT. Further studies with larger sample sizes are warranted.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: List of targeted 224 genes. The red symbols indicate genes in which significant mutations were detected in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M., S.S. and K.K.; methodology, H.M., S.S. and K.K.; validation, H.M., S.S. and K.K.; formal analysis, H.M. and S.S.; investigation, H.M., S.S. and K.K.; resources, H.M., S.S., K.K., W.K., T.N., Y.T., Y.A., Y.S., N.A.; data curation, H.M. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.; writing—review and editing, S.S., K.K., W.K., T.N., Y.T., Y.A., Y.S., and A.N.; visualization, H.M.; supervision, K.K. and A.N.; project administration, H.M.; funding acquisition, H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSJP) KAKENHI (grant number: JP20K16731).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This single-center, prospective, observational study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of the Ryukyus (approval number: 1649).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Takuya Fukushima for kindly providing the research laboratory space and equipment.

Conflicts of Interest

Kennosuke Karube received research grants from Eisai Co. Ltd. and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Akihiro Nishie received a research grant from Canon Medical Systems Corporation. Both grants did not involve the submitted work. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCRT |

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy |

| NGS |

Next-generation sequencing |

| SCC |

Squamous cell carcinoma |

| AC |

Adenocarcinoma |

| RT |

Radiotherapy |

| FIGO |

Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

| ECOG |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| PS |

Performance status |

| SNP |

Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| CTCAE |

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| EBRT |

External beam radiotherapy |

| 3D-IGBT |

Three-dimensional-image-guided brachytherapy |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| HR-CTV |

High-risk clinical target volume |

| JROSG |

Japanese Radiation Oncology Study Group |

| LC |

Local control |

| EQD2 |

Equivalent dose 2 Gy per fraction |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marth, C.; Landoni, F.; Mahner, S.; McCormack, M.; Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Colombo, N. on behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cervical cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, iv72–iv83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guida, F.; Kidman, R.; Ferlay, J.; Schüz, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Kithaka, B.; Ginsburg, O.; Vega, R.B.M.; Galukande, M.; Parham, G.; et al. Global and regional estimates of orphans attributed to maternal cancer mortality in 2020. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2563–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.A.; Letai, A.; Fisher, D.E.; Flaherty, K.T. Precision medicine for cancer with next-generation functional diagnostics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojesina, A.I.; Lichtenstein, L.; Freeman, S.S.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Imaz-Rosshandler, I.; Pugh, T.J.; Cherniack, A.D.; Ambrogio, L.; Cibulskis, K.; Bertelsen, B.; et al. Landscape of genomic alterations in cervical carcinomas. Nature 2014, 506, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature 2017, 543, 378–384.

- Yoshimoto, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Murata, K.; Noda, S.-E.; Miyasaka, Y.; Hamamoto, J.; Furuya, M.; Hirato, J.; Suzuki, Y.; Ohno, T.; et al. Mutation profiling of uterine cervical cancer patients treated with definitive radiotherapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 159, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, W.; Shen, X.; Yang, W.; Wu, X.; Yang, H. Comprehensive analysis of targetable oncogenic mutations in chinese cervical cancers. Oncotarget 2014, 6, 4968–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xiang, L.; Pei, X.; He, T.; Shen, X.; Wu, X.; Yang, H. Mutational analysis of KRAS and its clinical implications in cervical cancer patients. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Jiang, W.; Ye, S.; He, T.; Pei, X.; Li, J.; Chan, D.W.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Li, F.; Tao, P.; et al. ERBB2 mutation: A promising target in non-squamous cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 148, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rochefordiere, A.; Kamal, M.; Floquet, A. PIK3CA Pathway Mutations Predictive of Poor Response Following Standard Radiochemotherapy ± Cetuximab in Cervical Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res 2015, 21, 2530–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Jiang, W.; Li, J.; Shen, X.; Yang, W.; Yang, G.; Wu, X.; Yang, H. PIK3CA mutation analysis in Chinese patients with surgically resected cervical cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, T.K.; Cheung, T.H.; Yim, S.F.; Yu, M.Y.; Chiu, R.W.; Lo, K.W.; Lee, I.P.; Wong, R.R.; Lau, K.K.; Wang, V.W.; et al. Liquid biopsy of PIK3CA mutations in cervical cancer in Hong Kong Chinese women. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 146, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X. Emerging role of mutations in epigenetic regulators including MLL2 derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas for cervical cancer. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Guo, Q.-H.; Zhou, X.-L.; Wu, X.-H.; Li, J. Genomic Profiling of Chinese Cervical Cancer Patients Reveals Prevalence of DNA Damage Repair Gene Alterations and Related Hypoxia Feature. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 792003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi-Kabata, Y.; Nakazono, K.; Takahashi, A.; Saito, S.; Hosono, N.; Kubo, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Kamatani, N. Japanese Population Structure, Based on SNP Genotypes from 7003 Individuals Compared to Other Ethnic Groups: Effects on Population-Based Association Studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 83, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, O.; Katagiri, T.; Tsunoda, T.; Harima, Y.; Nakamura, Y. Classification of Sensitivity or Resistance of Cervical Cancers to Ionizing Radiation According to Expression Profiles of 62 Genes Selected by cDNA Microarray Analysis. Neoplasia 2002, 4, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harima, Y.; Togashi, A.; Horikoshi, K.; Imamura, M.; Sougawa, M.; Sawada, S.; Tsunoda, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Katagiri, T. Prediction of outcome of advanced cervical cancer to thermoradiotherapy according to expression profiles of 35 genes selected by cDNA microarray analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2004, 60, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harima, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Utsunomiya, K.; Shiga, T.; Komemushi, A.; Kojima, H.; Nomura, M.; Kamata, M.; Sawada, S. Identification of Genes Associated With Progression and Metastasis of Advanced Cervical Cancers After Radiotherapy by cDNA Microarray Analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2009, 75, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.-S.; Huang, M.-N.; Song, Y.-M.; Li, N.; Wu, L.-Y.; Zhan, Q.-M. A preliminary study of genes related to concomitant chemoradiotherapy resistance in advanced uterine cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Chin. Med J. 2013, 126, 4109–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Huang, W.; Zou, S.; Shen, Q.; Zhu, X. A Five-Genes-Based Prognostic Signature for Cervical Cancer Overall Survival Prediction. Int. J. Genom. 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Gao, C.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Z. Identification of Prognostic miRNA Signature and Lymph Node Metastasis-Related Key Genes in Cervical Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Qian, Z.; Gong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Han, Y.; Yi, X.; Huang, W.; Ji, L.; Xu, J.; et al. Comprehensive genomic variation profiling of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer identifies potential targets for cervical cancer early warning. J. Med Genet. 2018, 56, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholl, S.; Popovic, M.; de la Rochefordiere, A.; Girard, E.; Dureau, S.; Mandic, A.; Koprivsek, K.; Samet, N.; Craina, M.; Margan, M.; et al. Clinical and genetic landscape of treatment naive cervical cancer: Alterations in PIK3CA and in epigenetic modulators associated with sub-optimal outcome. EBioMedicine 2019, 43, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN Guidelines Version 4.2024. Cervical Cancer. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Kandoussi, I.; El Haddoumi, G.; Mansouri, M.; Belyamani, L.; Ibrahimi, A.; Eljaoudi, R. Overcoming Resistance in Cancer Therapy: Computational Exploration of PIK3CA Mutations, Unveiling Novel Non-Toxic Inhibitors, and Molecular Insights Into Targeting PI3Kα. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Liu, H.; Yuan, Z.; Zundell, J.; Towers, M.; Lin, J.; Lombardi, S.; Nie, H.; Murphy, B.; Yang, T.; et al. Targeting the mevalonate pathway suppresses ARID1A-inactivated cancers by promoting pyroptosis. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 740–756e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Jing, P.; Cao, L.; Li, N.; Li, X.; Yao, L.; Zhang, J. Targeting FBW7 as a Strategy to Overcome Resistance to Targeted Therapy in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 3527–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, L.M.; Miller, T.W. Therapeutic Targeting of Cancers with Loss of PTEN Function. Curr. Drug Targets 2014, 15, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, S.; Iwakuma, T. Drugs Targeting p53 Mutations with FDA Approval and in Clinical Trials. Cancers 2023, 15, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; He, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Pan, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zeng, W.; Chen, D.; Xing, W. Comprehensive Analysis to Identify the Encoded Gens of Sodium Channels as a Prognostic Biomarker in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Genet. 2022, 12, 802067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; Zhou, S.; Ding, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, W.; Xu, M. IL1RN and PRRX1 as a Prognostic Biomarker Correlated with Immune Infiltrates in Colorectal Cancer: Evidence from Bioinformatic Analysis. Int. J. Genom. 2022, 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhou, K.; Li, M.; Hu, Q.; Wei, W.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Q. Identification of SCN7A as the key gene associated with tumor mutation burden in gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, P.; Rao, W.; Lin, Z.; Liu, S.; Lin, X.; Wu, C.; Lin, X.; Hu, Z.; Ye, W. Genomic analyses reveal SCN7A is associated with the prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Esophagus 2022, 19, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Qiu, M.; Xu, Y.; Mao, Q.; Wang, J.; Dong, G.; Xia, W.; Yin, R.; Xu, L. Differentially expressed protein-coding genes and long noncoding RNA in early-stage lung cancer. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 9969–9978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, L.; Young, R.; Henrich, I.C. JAK1-STAT3 signals are essential effectors of the USP6/TRE17 oncogene in tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 5337–5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, H.; He, Y.; Li, T.; Feng, J.; Chen, W.; Ao, L.; Shi, X.; Lin, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Ubiquitin-Specific Protease USP6 Regulates the Stability of the c-Jun Protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, I.C.; Jain, K.; Young, R.; Quick, L.; Lindsay, J.M.; Park, D.H.; Oliveira, A.M.; Blobel, G.A.; Chou, M.M. Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 6 Functions as a Tumor Suppressor in Ewing Sarcoma through Immune Activation. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 2171–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pötter, R.; Tanderup, K.; Schmid, M.P.; Jürgenliemk-Schulz, I.; Haie-Meder, C.; Fokdal, L.U.; Sturdza, A.E.; Hoskin, P.; Mahantshetty, U.; Segedin, B.; et al. MRI-guided adaptive brachytherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer (EMBRACE-I): a multicentre prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maemoto, H.; Ogura, T.; Toita, T.; Ariga, T.; Hashimoto, S.; Kawakami, Y.; Ishikawa, K.; Takehara, S.; Heianna, J.; Kudaka, W.; et al. Small dose of oral gastrografin for computed tomography-based image-guided brachytherapy in patients with uterine cervical cancer. J. Radiat. Res. 2021, 63, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).