1. Introduction

Cervical cancer ranks 4th in the structure of oncological diseases and cancer mortality among women in 2022, with approximately 660,000 new cases and around 350,000 deaths reported worldwide. A significant trend has been noted in the increasing prevalence of cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, and Southeast Asia. Of the 350,000 deaths caused by cervical cancer, 94% occurred in low- and middle-income countries [

1,

2].

Infection caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) remains a major risk factor for developing cervical cancer. Additionally, many other genetic and epigenetic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer [

3]. Cervical cancer is predominantly classified as either squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, and its development may be influenced by potentially oncogenic germline mutations. Notably, squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix exhibit different molecular profiles [

4]. Most known cancer predisposition genes are involved in maintaining genomic integrity, protecting DNA from mutations that could ultimately lead to malignant tumors. Current data suggest that, besides increasing cancer risk, germline variants also affect tumor progression, shaping the landscape of somatic alterations in cancer [

5,

6].

Recently, several studies have been conducted to identify germline variants in patients with cervical cancer, aiming to discover predisposition genes or factors influencing disease progression. A meta-analysis of GWAS identified several candidate genes most likely associated with cervical cancer predisposition, including

PAX8/PAX8-AS1, LINC00339, CDC42, CLPTM1L, HLA-DRB1, and

GSDMB [

7]. Despite numerous sequencing studies, the genetic characteristics of cervical cancer are still not fully understood, particularly in populations not included in GWAS. Lin Qiu and colleagues conducted a parallel study on the Chinese population using a multigene NGS panel targeting 571 cancer-related genes. In this study, a total of 810 somatic variants, 2730 germline mutations, and 701 copy number variations (CNVs) were detected. The genes FAT1, HLA-B, PIK3CA, MTOR, KMT2D, and ZFHX3 were the most frequently mutated. Additionally, loci in the genes PIK3CA, BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, and TP53 exhibited a higher frequency of CNVs. This study demonstrated that genetic variations not only influence the predisposition to cervical cancer but also affect the resistance of cervical cancer to radiotherapy. However, additional studies involving larger patient cohorts are required to confirm these findings [

8]. A study by Hao Wen and colleagues on the prevalence of pathogenic and potentially pathogenic germline variants in 62 cancer predisposition genes in the Chinese population demonstrated that the prevalence of pathogenic and potentially pathogenic variants was 6.4% (23 out of 358) for cervical cancer [

9].

The aim of this study is to identify germline mutations in proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that play key roles in the molecular pathogenesis of tumors. By considering clinical data from patients, we aim to assess the significance of these mutations in forming genetic predispositions to cervical cancer and their impact on disease progression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Samples

The study sample consisted of 108 unrelated women with a clinical diagnosis of cervical cancer residing in the Republic of Bashkortostan (a region at the crossroads of Eastern Europe and Asia). The examination, final diagnosis, and treatment of the patients were carried out at the Republican Clinical Oncology Dispensary of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Bashkortostan. The sample includes women born between 1951 and 1994, with an average age of 50 years. The HPV status of most patients is not formally documented, as it is generally presumed positive and does not influence the treatment approach. The choice of treatment method for cervical cancer is determined individually and depends on the extent of the tumor process and the severity of concomitant somatic pathology. The primary treatment strategy for this cohort of patients at stages IA1-IA2 is surgical intervention, while at stages IB and IIA, surgical treatment or radiation therapy/chemoradiotherapy may be applied. At stages IIB–IVA, the standard treatment is chemoradiotherapy under a radical protocol—combined radiation therapy (external beam radiation therapy + brachytherapy) with weekly administration of cisplatin at 40 mg/m² for 5–6 cycles during external beam radiation therapy [

10,

11]. The majority of women in the study sample had squamous cell carcinoma (89.1%), while adenocarcinomas, including mucinous tumors, accounted for 7.92%, adenosquamous cervical cancer for 0.99%, aplastic cervical cancer for 0.99%, and leiomyosarcoma for 0.99%, with varying degrees of differentiation and stages of disease from in situ to metastatic. The women in the sample represented the three most common ethnic groups in the Republic of Bashkortostan: Russians, Tatars, and Bashkirs. The comparison group for the TP53 gene polymorphism rs1042522 and the SNP rs17879961 in the CHEK2 gene consisted of DNA from 51 women who had cleared HPV, indicating that the virus did not persist or lead to cervical cancer. For additional studies aimed at determining microsatellite instability in the somatic DNA of patients with potentially pathogenic variants in the dMMR gene system in germline DNA, histological blocks with formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded malignant tumor tissue were used.

2.2. NGS Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes using the phenol-chloroform extraction method as described by Mathew (1984). The concentration and purity of the extracted DNA were assessed using a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Singapore) and 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. A custom NGS panel was used in the study to analyze 48 genes, 27 of which function as proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressors (

Table 1). The panel was primarily designed to study exons. However, due to the random fragmentation of DNA during the initial pre-processing step, the resulting fragments may include both targeted regions and adjacent intronic regions. Consequently, variants were also identified in the intronic regions of the genes. The 37th genomic assembly (GRCh37UCSC) was used to assign and search for genomic coordinates in this study. Sample libraries for NGS analysis were prepared using the KAPA Hyper Cap Workflow v3.0 reagent kit (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). All steps of the library preparation, including multiplexing, hybridization, and enrichment, were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. NGS sequencing was performed using the MiSeq Series next-generation sequencer with the MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (300-cycles) (Illumina, USA).

2.3. Data Processing and Additional Studies

Secondary analysis of the obtained FASTQ files was performed separately for each sample using a BED file containing genomic coordinates and a Manifest file with a similar coordinate format, within the Illumina BaseSpace cloud data analysis service, specifically using the “BWA Enrichment” application (Illumina, USA). As a result, we obtained VCF files containing information about sequence variations in the studied DNA compared to the reference genome, and we analyzed the samples using the Variant Interpreter database (Illumina, USA). The identified nucleotide sequence variations were classified into six groups: benign (B), likely benign (LB), pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), variants of uncertain significance (VUS), and variants absent from the utilized database. Subsequent verification and analysis of the clinical significance of the detected mutations were conducted using the “ClinVar,” “BSKN,” and “OncoBRCA” databases, taking into account clinical information. Data on the prevalence of variants and pathogenicity prediction program calculations (CADD, REVEL, SpliceAI, Pangolin, PolyPhen, phyloP) were obtained using the online resources “Ensembl” and “GnomAD” (v4.0.0). Functional analysis of the protein products was performed using resources for building protein spatial models and determining changes within them: “SWISS-MODEL,” “DynaMut2,” “UniProt.” Statistical data processing was carried out using the Plink web resource for whole-genome association analysis (

https://zzz.bwh.harvard.edu/plink/data.shtml), utilizing Microsoft Windows tools, including Excel and Notepad. The significance threshold was set at p<0.05. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for rs1042522 was conducted using TaqMan technology with the “Syntol” reagent kit (Russia) and the “CFX96” detecting amplifier (BioRad, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-PCR for rs17879961 was conducted using polymorphism detection reagents from “DNA-Synthesis” (Russia) with the “DTprime” real-time PCR detection system (DNA Technology, Russia), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The rs17879961 variant was selected for additional study due to its frequency of 2.7% among cervical cancer patients, compared to 0.92% for other pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants. Immunohistochemical analysis of microsatellite instability, performed using the “VENTANA MMR” panel, and molecular-genetic analysis of microsatellite instability (MSI) were conducted on a commercial basis

3. Results

3.1. Germinal Landscape of Nucleotide Variats in Proto-Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressor Genes

In a study conducted on a cohort of women clinically diagnosed with cervical cancer, 148 nucleotide sequence substitutions were identified in genes directly implicated in tumorigenesis (

Table 2). Among them, 35 (23.6%) are classified as benign based on literature and database information, while 105 (70.9%) are categorized as variants of uncertain significance (VUS) whose clinical impact is yet to be determined. The majority of variants with uncertain significance (22 out of 26) were found in the

ROS1 gene, likely due to the inclusion of its intronic regions in the target panel.

Seven variants (4.7%) were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. Among these, the rs1042522 polymorphic variant in the TP53 gene has been associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer in several studies (0.6%) (

Table 3).

3.2. Analysis of the Effect of P and LP Germinal Variants on the Course of Cervical Cancer

3.2.1. Nucleotide Sequence Variants in the TP53 Gene

Nucleotide substitutions in the TP53 gene accounted for 4.7% of the detected variants among women with cervical cancer. Six out of seven variants belong to the category of variants of uncertain significance (VUS), and only one – the proline to arginine substitution at position 72 – has been a topic of considerable scientific discussion.

In 87.0% of the patients (94/108), a missense substitution was identified in codon 72 of the TP53 gene (c.215C>G, p.Pro72Arg, rs1042522, chr17:7579472), 44 of which were in the homozygous state, and 50 in the heterozygous state.

Mutations in the

TP53 gene are common genetic events in most types of cancer, leading to increased cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis, and often resulting in genetic instability. The effect of the p.Pro72Arg variant of the TP53 gene in different types of cancer is debated. For example, Storey A. and colleagues demonstrated that the Arg72 protein variant in the homozygous state increases susceptibility to HPV-associated cervical cancer by sevenfold [

12]. However, a subsequent study by Yasutaka Kawamata and colleagues showed that the expression level of the p53 protein in normal human keratinocytes for each codon 72 p53 genotype was not affected by the introduction of HPV 16-E6 from recombinant adenovirus, and p53 mRNA was activated independently of the p53 genotypes when HPV 16-E6 was expressed. Statistical analysis did not reveal a link between TP53 genotypes and the development of cervical neoplasms [

13]. Hugo Sousa and colleagues concluded, after reviewing literature data and conducting meta-analyses, that this variant segregates differently among various ethnic groups. Therefore, the possible role of this genetic variant may be linked to a specific genetic background, which could explain why some studies report an increased risk of cervical cancer associated with the arginine variant of TP53 [

14]. Orsted D.D. and colleagues demonstrated that the p.Pro72Arg polymorphism affects overall survival in cancer patients in the general population. The 12-year overall survival rate increased by 3% (P=0.003) in heterozygous p53Arg/Pro carriers and by 6% (P=0.002) in p53Pro/Pro homozygotes compared to p53Arg/Arg homozygotes, which corresponds to a 3-year increase in median survival for Pro/Pro homozygotes compared to Arg/Arg. Thus, the p53 Arg72Pro polymorphism leads to increased overall survival but does not reduce cancer risk [

15]. In a later study involving a cohort of cervical cancer patients, the polymorphism was shown to affect overall survival, with p53Arg/Pro carriers having a median survival of 126 months compared to 111 months for p53Arg/Arg and p53Pro/Pro genotypes (P=0.047) [

16].

In our study, no significant associations were identified between the alleles and genotypes of the rs1042522 locus of the TP53 gene and cervical cancer.

In 97% of the women, cervical cancer was diagnosed in late 2020 or early 2021, limiting our analysis to three-year survival data. Combined chemoradiotherapy was successful in 71 out of 106 patients (67%), while 35 (33%) did not achieve a sufficient therapeutic response; however, no correlations were found between genotypes and response to therapy. The median age of cervical cancer onset was 53.5 years for patients with the CC genotype, 52.3 years for CG, and 47.6 years for GG. This difference of up to 5.9 years in median age suggests an earlier onset of cervical cancer in carriers of the homozygous p53Arg/Arg variant.

The obtained results suggest that a pharmacogenomic approach based on patient genetic profiles, including TP53 genotype analysis, could be used to individualize treatment and optimize therapeutic methods, potentially improving clinical outcomes and reducing toxicity.

3.2.2. Co-Carriage of Variants in the APC and BRAF Genes in a Patient with Cervical Cancer

The p.(Ser836Ter) variant in the APC gene (c.2507C>G, chr5:112173798) in the heterozygous state was detected in one woman (0.92%). his substitution is considered pathogenic as it creates a stop codon and is predicted to result in premature truncation of the protein. According to the Uniprot database, mutations in this gene are associated with diseases such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) type 1, hereditary desmoid disease, medulloblastoma, gastric cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric adenocarcinoma, and proximal gastric polyposis.

Germline variants in kinases identified in the study represent 45.3% of the detected variants (67 out of 148). Among these, only one variant in the BRAF gene is considered pathogenic.

The missense variant p.(Trp531Leu) in the BRAF gene (c.1592G>T, chr7:140476814, rs397507478) in the heterozygous state was detected in one woman (0.92%). According to the ClinVar database, this substitution is considered pathogenic; however, detailed functional analysis data for this variant are not available. Using the wild-type BRAF protein structure model built with ‘SWISS-MODEL’ and analyzed with ‘DynaMut2,’ we determined that the substitution of tryptophan with leucine at position 531 results in destabilization of the protein, with a score of -2.42 kcal/mol (ΔΔGStability). Nevertheless, the substitution of codon TGG with TTG is predicted to be benign according to six prediction programs (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD, REVEL, MetaLR, MutationAssessor).

However, given that, the p.Trp531Leu substitution occurs in the protein kinase domain and that a pathogenic variant leading to a nonsense codon is located at the same genomic position, functional studies are required to accurately determine its clinical significance. The identification of activating mutations in the

BRAF gene across various malignancies has facilitated the development of effective

BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib (Zelboraf) and dabrafenib [

17]. Although the V600E mutation is most frequently identified among

BRAF mutations, the spectrum of mutations in the

BRAF gene continues to expand with the advent of next-generation sequencing [

18].

Two missense substitutions, p.Ser836Ter in the APC gene and p.Trp531Leu in the BRAF gene, were identified in a patient born in 1959. She sought medical help in 2021 due to a recurrence of cervical cancer. The initial diagnosis was made in 2020 and was described as stage 4, grade 4 cervical cancer with metastases to the iliac lymph nodes and peritoneal metastases (T4N1M1) (according to ICD-10: C53.8). The patient passed away in November 2021, as the disease progressed aggressively. Such co-carriage of two mutations in the tumor suppressor gene and the serine/threonine protein kinase gene has not been described in the literature.

3.2.3. Nucleotide Variants in the CHEK2 Gene

Germline mutations in genes encoding proteins that regulate DNA repair and the response to double-strand DNA breaks have been recognized as pathogenic factors contributing to hereditary cancer predisposition. The

ATM-CHEK2-TP53 gene group has been shown to initiate the primary DNA damage response and acts as a barrier to cancer development. Pathogenic germline mutations in the

CHEK2 gene are among the most frequent alterations in various tumors, and their role has been confirmed in gender-specific cancers such as breast and prostate cancer [

19].

Among the identified variants, substitutions in the CHEK2 gene account for 6 out of 148 (4%). Five of these are categorized as VUS, and one is pathogenic.

The missense variant p.(Ile157Thr) in the

CHEK2 gene (c.470T>C, rs17879961, chr22:29121087) in the heterozygous state was detected in three women (2.7%). One patient had a combination of cervical adenocarcinoma (T3bN0M0) and breast cancer. Cervical cancer manifested at the age of 73, with a fatal outcome within a year. In patients with squamous cell cervical cancer, the disease manifested at ages 49 (T2bN1M0) and 62 (T2aN0M0). Although six in silico predictive programs interpret this substitution as benign (CADD, REVEL, SpliceAI, Pangolin, PolyPhen, phyloP), it is still considered likely pathogenic in breast cancer [

20] and pathogenic or likely pathogenic in cancer predisposition syndromes [

21,

22]. According to the ‘OncoBRCA’ database, this variant is classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic for several types of cancer, including breast cancer and other malignancies. According to the ‘GnomAD’ database (v4.0.0.), the minor allele frequency of this variant is 0.003 in the general population. According to the ‘UniProt’ database, the substitution of isoleucine with threonine at position 157 of the

CHEK2 protein occurs in the FHA domain, a region critical for the protein’s role in DNA damage response. Using the wild-type protein structure built with ‘SWISS-MODEL’ and analyzed with ‘DynaMut2,’ we found that this substitution is destabilizing, with a score of -1.2 kcal/mol (ΔΔGStability). As an additional study, we investigated the frequency of this substitution in a comparison group of healthy women with a history of spontaneous HPV elimination. Based on these findings, we concluded that these women are not predisposed to persistent HPV carriage and, consequently, to cervical cancer. As a result, we found that 3 (5.88%) of 51 women in the comparison group carried the pathogenic p.(Ile157Thr) variant in the

CHEK2 gene in the heterozygous state. Given that the frequency of this pathogenic variant is higher in the comparison group (5.88%) than in the cervical cancer patient group (2.7%), we concluded that this mutation is not associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. However, it is still premature to draw conclusions about whether this substitution affects disease progression.

3.2.4. Germinal Variants in the BRCA2 Gene

BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins play a key role in regulating DNA repair and maintaining genome integrity [

23]. In our study, 16 (10.81%) variants were identified in these genes, one of which was pathogenic.

The missense variant p.(Arg3052Trp) in the BRCA2 gene (c.9154C>T, chr13:32954180, rs45580035) in the heterozygous state was detected in 1 woman (0.92%). According to multiple databases, this variant is classified as pathogenic for cancer predisposition syndromes, including hereditary breast and ovarian cancers. This variant was identified in a patient who developed squamous cell cervical cancer (T3N1M0) at the age of 58, resulting in a fatal outcome within 2 years.

Twin studies have estimated the heritability of obesity within the range from 40% to 75% [126]. Many of the candidate genes and metabolic pathways associated with body weight regulation were initially identified in obese mice, which spontaneously develop severe hyperphagia and obesity [42]. In particular, leptin deficiency was associated with the development of severe obesity in mice, and the genes encoding leptin and the leptin receptor were further identified and cloned [43]. In addition, the melanocortin pathway, which regulates body weight, was also identified in mice; as a result, a wide range of new candidate genes responsible for obesity has come to light [44].

3.2.5. Mutations in Genes of the Mismatch Repair System

Mutations in mismatch repair (

MMR) genes, such as

MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and

PMS2, are associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome). The MMR system recognizes and corrects DNA errors caused by mismatched nucleotides. MSH proteins play a crucial role in recognizing these mismatches and initiating the repair process [

24]. Seventeen out of 148 variants (11.4%) identified in our study were found in these genes. Of these, 3 out of 17 variants were pathogenic or likely pathogenic.

The variant p.(Trp117Ter) in the MSH2 gene (c.350G>A, chr2:47635679, rs786202083) in the heterozygous state was detected in one woman (0.92%). This variant is a nonsense variant, resulting in the replacement of tryptophan with a premature stop codon (TGG>TAG). It is expected to result in the loss of normal protein function due to truncation or nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. This mutation was found in a 48-year-old woman with a combination of cervical cancer and endometrial cancer. Immunohistochemical analysis of her endometrial tumor revealed microsatellite instability, and she is currently receiving the 9th line of immunotherapy with a satisfactory therapeutic response.

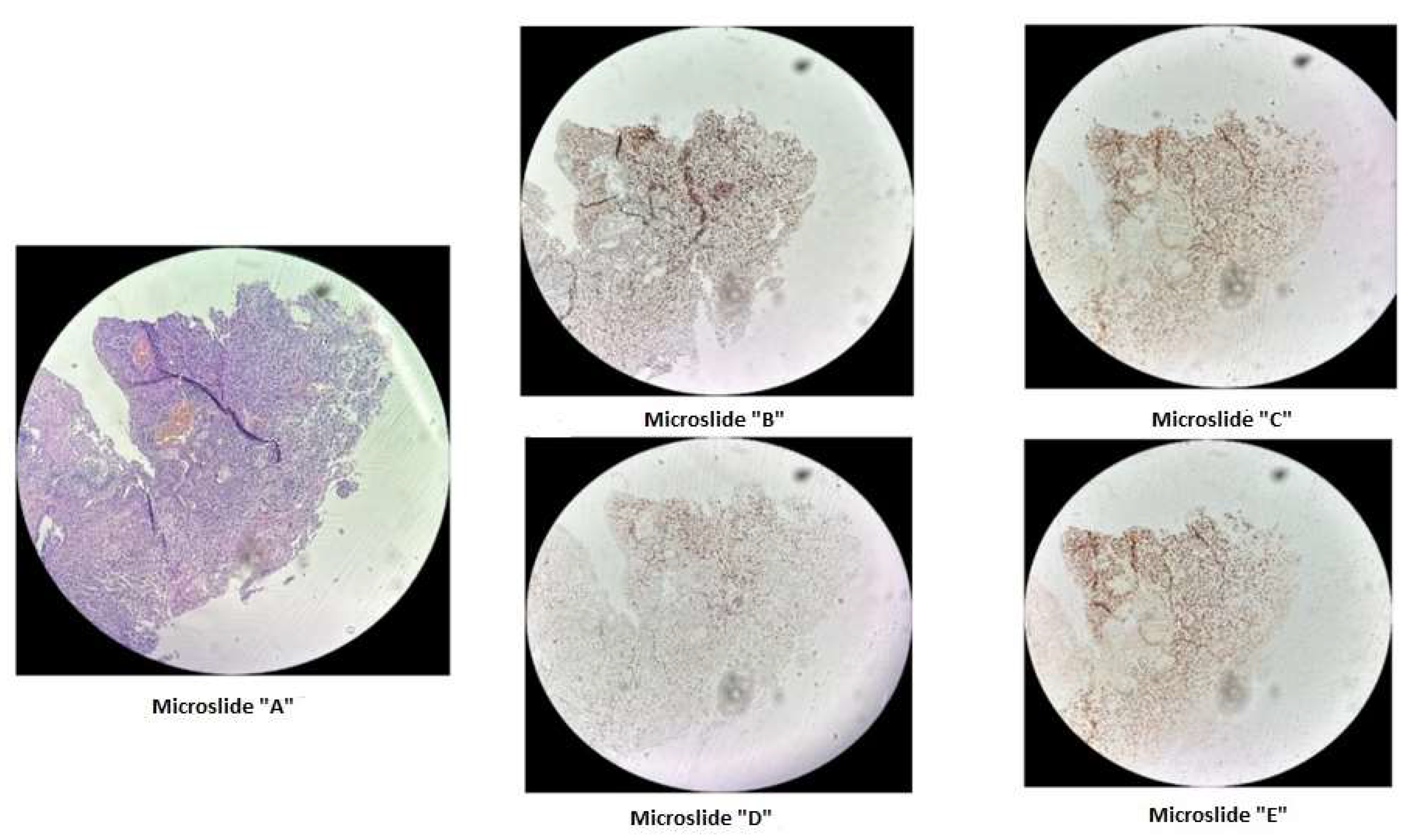

A microdeletion p.Asp706GlyfsTer11 ->G with a frameshift in the MSH2 gene at genomic coordinate chr2:47703614 was found in a woman born in 1963 who was diagnosed with stage 3B, grade 2 squamous cell cervical cancer in 2015, and at that time underwent a radical course of chemoradiotherapy (CRT). In 2021, due to disease recurrence, she underwent another course of CRT, followed by complications. The patient passed away in January 2022. This mutation is considered likely pathogenic, though its effects are not yet fully understood. However, reliable morphological and molecular genetic methods exist for diagnosing microsatellite instability in tissue. Therefore, we decided to conduct additional studies for this patient and others with similar mutations. On the diagnostic biopsy material of the primary tumor from a paraffin-embedded histological block from 2015, we performed an immunohistochemical study for microsatellite instability (dMMR) and did not detect loss of expression of MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, PMS2 in viable tumor cells (

Figure 1). Additionally, using fragment analysis on a 3500xL genetic analyzer, we analyzed five microsatellite loci: NR-21, BAT26, BAT-25, NR-24, and NR-27. The study revealed one allelic variation in the loci examined, indicating the absence of microsatellite instability. Previously, such results were interpreted as MSI-low; however, in 2018, at the ESMO consensus on the diagnosis of MMR deficiency, it was decided to consider the MSI-low status as non-existent [

25]. Thus, we can conclude that the germline substitution p.Asp706GlyfsTer11, ->G did not have a pathogenic effect on the tumor and is not clinically significant.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of cervical cancer preparation using the dMMR panel. Microslide A: G-E staining at X10 magnification / Microslide B: PMS2 antibody staining at X10 magnification / Microslide C: MSH2 antibody staining at X10 magnification / Microslide D: MLH1 antibody staining at X10 magnification / Microslide E: MSH6 antibody staining at X10 magnification. (Note: since the tissue block was prepared in 2015, some staining defects were observed due to the prolonged storage period of the material for immunohistochemical study; however, despite some staining heterogeneity, the expression of DNA mismatch repair proteins is preserved in viable tumor cells).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of cervical cancer preparation using the dMMR panel. Microslide A: G-E staining at X10 magnification / Microslide B: PMS2 antibody staining at X10 magnification / Microslide C: MSH2 antibody staining at X10 magnification / Microslide D: MLH1 antibody staining at X10 magnification / Microslide E: MSH6 antibody staining at X10 magnification. (Note: since the tissue block was prepared in 2015, some staining defects were observed due to the prolonged storage period of the material for immunohistochemical study; however, despite some staining heterogeneity, the expression of DNA mismatch repair proteins is preserved in viable tumor cells).

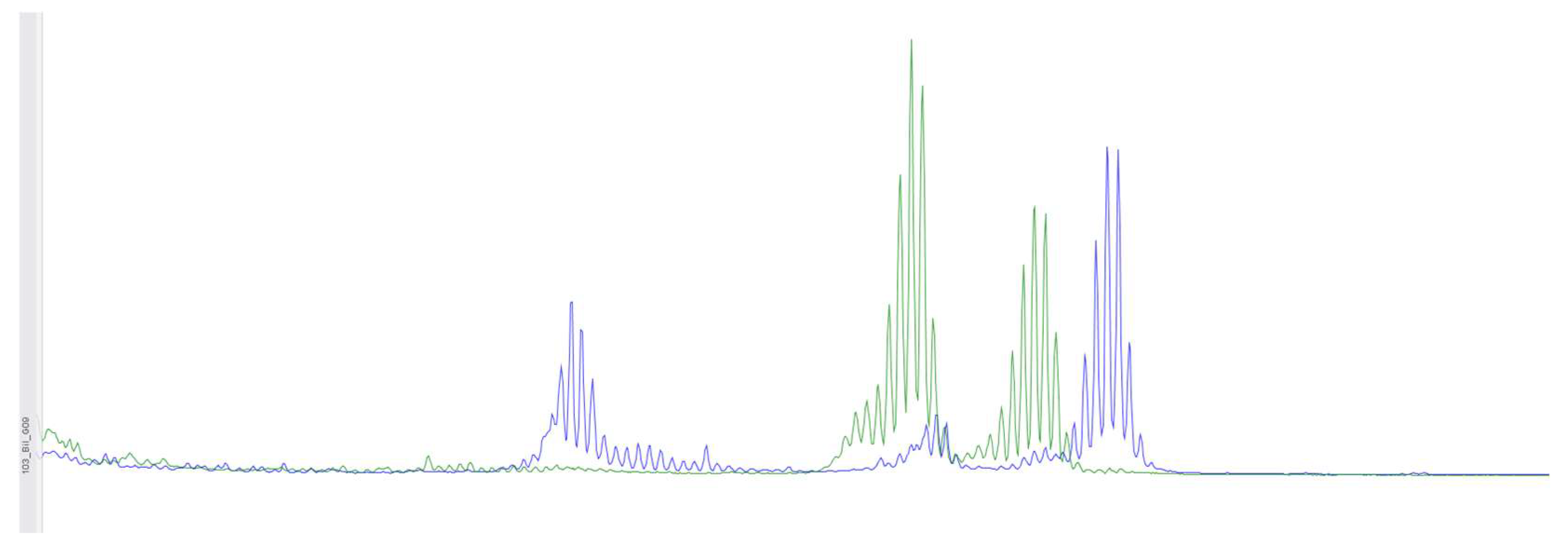

Figure 2.

Using fragment analysis on a 3500xL genetic analyzer, the study investigated 5 microsatellite loci: NR-21, BAT-26, BAT-25, NR-24, NR-27. As a result of the study, no microsatellite instability was detected.

Figure 2.

Using fragment analysis on a 3500xL genetic analyzer, the study investigated 5 microsatellite loci: NR-21, BAT-26, BAT-25, NR-24, NR-27. As a result of the study, no microsatellite instability was detected.

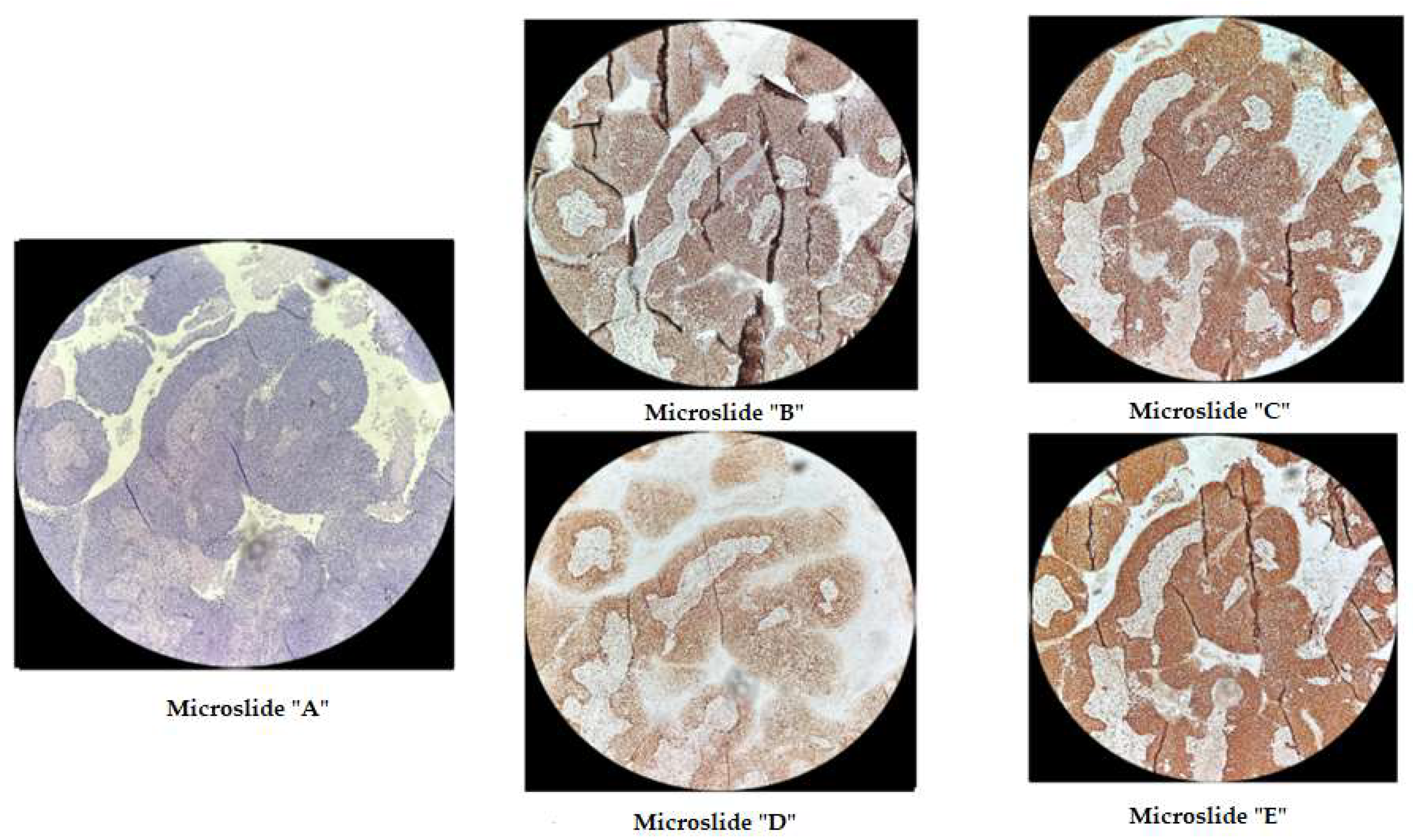

The p.Phe1088LeufsTer5 frameshift variant in the MSH6 gene at genomic coordinate chr2:48030639 was identified in a patient born in 1962 with moderately differentiated invasive squamous cell cervical cancer (stage IIb T2bN1M1nod grade IV), which was diagnosed in November 2021. In February 2022, after the progression of the disease, she underwent further examination and received a course of chemoradiotherapy (CRT). The disease progressed in the summer of 2023, and the patient passed away in the autumn of 2023. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on diagnostic biopsy material from the primary tumor in a paraffin-embedded histological block from 2022, demonstrating the retention of MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2 protein expression in viable tumor cells (

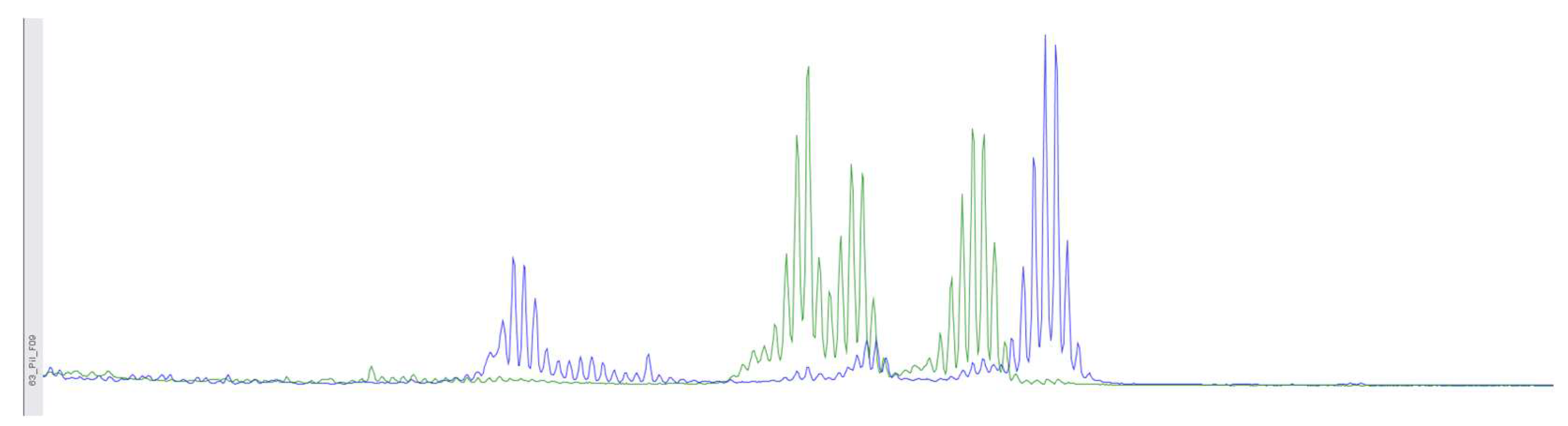

Figure 3). Additionally, fragment analysis on a 3500xL genetic analyzer investigated 5 microsatellite loci: NR-21, BAT26, BAT-25, NR-24, NR-27. The study revealed 2 allelic variants in the examined loci, indicating high microsatellite instability (MSI-High) (

Figure 4). Thus, it can be concluded that the germline p.Phe1088LeufsTer5 variant is pathogenic and influenced the course of the disease. This case of microsatellite instability detection reveals contradictory results between the two MSI detection methods. The literature suggests that, in certain situations, the IHC test may produce false-negative results in the presence of certain missense mutations or

MLH1 promoter methylation [

26]. It appears that in our case, the germline mutation in the

MSH6 gene, which was caused by a frameshift, should also be taken into consideration.

Based on the obtained results, it is advisable to use molecular genetic methods to detect microsatellite instability as a primary approach for patients with cervical cancer.

4. Conclusions

Cervical cancer (CC), like other malignancies, presents a complex and genetically heterogeneous disease profile. The clinical characteristics of the patients, along with the identified germline variants, enhance our understanding of the role of rare pathogenic and likely pathogenic mutations in the molecular pathogenesis of the disease. The clinical presentation of the patients suggests that pathogenic germline mutations significantly influence the course and outcome of the disease, leading to its deterioration.

From an oncogenetic perspective, these findings underscore the critical need for integrating germline genetic screening into the routine diagnostic and therapeutic management of cervical cancer. The identification of pathogenic germline variants not only provides insights into the genetic predisposition and underlying molecular mechanisms driving the disease but also has profound implications for personalized treatment strategies. For instance, patients harboring certain mutations may benefit from targeted therapies, such as PARP inhibitors in the context of BRCA mutations, or immune checkpoint inhibitors in cases associated with microsatellite instability. Additionally, understanding the specific genetic alterations in CC can facilitate the development of novel therapeutic approaches aimed at mitigating the impact of these mutations.

Moreover, the identification of these germline mutations has implications beyond the affected individual, extending to at-risk family members who may also carry these variants. This highlights the importance of genetic counseling and testing as a critical component of oncogenetic care, enabling risk assessment and preventive measures for relatives.

Further research is warranted to delineate the full spectrum of germline mutations associated with cervical cancer and to clarify their functional roles in tumorigenesis. Large-scale genomic studies, coupled with functional assays, will be instrumental in uncovering novel genetic drivers and refining the classification of variants of uncertain significance (VUS). This, in turn, may lead to the discovery of new biomarkers for early detection, prognosis, and therapeutic response, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

In conclusion, advancing our understanding of the genetic landscape of cervical cancer through comprehensive germline analysis represents a pivotal step toward more precise and effective cancer management, paving the way for a new era of personalized oncology.

Data availability statements: The data generated in the present study may be requested from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing – review and editing, K.L., R.Kh., N.M. and I.R.; methodology, R.K. and I.R.; data curation, formal analysis, K.L., R.M., A.Z. and I.G.; writing – original draft preparation, K.L., R.Kh. and I.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (agreement No. 075-15-2022-310 from 20 April 2022) and partially supported by St. Petersburg State University, ID PURE project: 103964756.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Institute of Biochemistry and Genetics RAS (protocol code: 19, Date: 25 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Institute of Biochemistry and Genetics RAS, and signed informed consent was obtained from all of the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Available online https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papilloma-virus-and-cancer. (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Smirnova, T. L.; Yastrebova, S. A.; Dakhmani, N. Analysis of the incidence of cervical cancer In Proceedings of the International scientific and practical conference Digital technologies in scientific development: new conceptual approaches (ICOIR OMEGA SCIENCE 2024), Ufa, Russia, 12 May 2024; pp.177-179.

- Revathidevi, S.; Murugan, A.K.; Nakaoka, H.; Inoue, I.; Munirajan, A.K. APOBEC: A molecular driver in cervical cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2021, 496, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.A; Howitt, B.E; Myers, A.P; Dahlberg, S.E; Palescandolo, E; Van Hummelen, P; MacConaill, L.E; Shoni, M; Wagle, N; Jones, R.T; Quick, C.M; Laury, A; Katz, I.T; Hahn, W.C; Matulonis, U.A; Hirsch, M.S. Oncogenic mutations in cervical cancer: genomic differences between adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix. Cancer. 2013, 119, 3776-83. [CrossRef]

- Chanock, S.J. How the germline informs the somatic landscape. Nat Genet. 2021, 53, 1523–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, P.; Bandlamudi, C.; Jonsson, P.; Kemel, Y.; Chavan, S.S.; Richards, A.L.; Penson, A.V.; Bielski, C.M.; Fong, C.; Syed, A.; Jayakumaran, G.; Prasad, M.; Hwee, J.; Sumer, S.O.; de Bruijn, I.; Li, X.; Gao, J.; Schultz, N.; Cambria, R.; Galle, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Vijai, J.; Cadoo, K.A.; Carlo, M.I.; Walsh, M.F.; Mandelker, D.; Ceyhan-Birsoy, O.; Shia, J.; Zehir, A.; Ladanyi, M.; Hyman, D.M.; Zhang, L.; Offit, K.; Robson, M.E.; Solit, D.B.; Stadler, Z.K.; Berger, M.F.; Taylor, B.S. The context-specific role of germline pathogenicity in tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2021, 53, 1577-1585. [CrossRef]

- Koel, M.; Võsa, U.; Jõeloo, M.; Läll, K.; Gualdo, N.P.; Laivuori, H.; Lemmelä, S.; Estonian Biobank Research Team; FinnGen; Daly, M.; Palta, P.; Mägi, R.; Laisk, T. GWAS meta-analyses clarify the genetics of cervical phenotypes and inform risk stratification for cervical cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2023, 32, 2103-2116. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Feng, H.; Yu, H.; Li, M.; You, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yang, W.; Jiang, H.; Wu, X. Characterization of the Genomic Landscape in Cervical Cancer by Next Generation Sequencing. Genes (Basel). 2022, 31, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Xu, Q.; Sheng, X.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, X. Prevalence and Landscape of Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic Germline Variants and Their Association With Somatic Phenotype in Unselected Chinese Patients With Gynecologic Cancers. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6, e2326437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhlova, S.V.; Kravets, O.A.; Morkhov, K.Yu.; Nechushkina, V.M.; Saevets, V.V.; Tyulandina, A.S.; Urmancheeva, A.F. Practical recommendations for drug treatment of cervical cancer. RUSSCO practical recommendations, part 1. Malignant tumors. 2023, 13, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Yashar, C.M.; Arend, R.; Barber, E.; Bradley, K.; Brooks, R.; Campos, S.M.; Chino, J.; Chon, H.S.; Crispens, M.A.; Damast, S.; Fisher, C.M.; Frederick, P.; Gaffney, D.K.; Gaillard, S.; Giuntoli, R.; Glaser, S.; Holmes, J.; Howitt, B.E.; Lea, J.; Mantia-Smaldone, G.; Mariani, A.; Mutch, D.; Nagel, C.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Podoll, M.; Rodabaugh, K.; Salani, R.; Schorge, J.; Siedel, J.; Sisodia, R.; Soliman, P.; Ueda, S.; Urban, R.; Wyse, E.; McMillian, N.R.; Aggarwal, S.; Espinosa, S. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Cervical Cancer, Version 1. 2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023, 21, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, A.; Thomas, M.; Kalita, A.; Harwood, C. ; Gardiol, D, Mantovani, F. ; Breuer, J.; Leigh, I.M.; Matlashewski, G.; Banks, L. Role of a p53 polymorphism in the development of human papillomavirus-associated cancer. Nature. 1998, 2, 229–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamata, Y.; Mitsuhashi, A.; Unno, Y.; Kado, S.; Shino, Y.; Uesugi, K.; Eguchi, O.; Ishii, J.; Seki, K.; Sekiya, S.; Shirasawa, H. HPV 16-E6-mediated degradation of intrinsic p53 is compensated by upregulation of p53 gene expression in normal cervical keratinocytes. Int J Oncol. 2002, 21, 561–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, H.; Santos, A.M.; Pinto, D.; Medeiros, R. Is there a biological plausability for p53 codon 72 polymorphism influence on cervical cancer development? Acta Med Port. 2011, 24, 127–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørsted, D.D.; Bojesen, S.E.; Tybjaerg-Hansen, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Tumor suppressor p53 Arg72Pro polymorphism and longevity, cancer survival, and risk of cancer in the general population. J Exp Med. 2007, 204, 1295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Nogueira, A.; Soares, S.; Assis, J.; Pereira, D.; Bravo, I.; Catarino, R.; Medeiros, R. TP53 Arg72Pro polymorphism is associated with increased overall survival but not response to therapy in Portuguese/Caucasian patients with advanced cervical cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018, 15, 8165–8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulikakos, P.I.; Sullivan, R.J.; Yaeger, R. Molecular Pathways and Mechanisms of BRAF in Cancer Therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 4618–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaeger, R.; Kotani, D.; Mondaca, S.; Parikh, A.R.; Bando, H.; Van Seventer, E.E.; Taniguchi, H.; Zhao, H.; Thant, C.N.; de Stanchina, E.; Rosen, N.; Corcoran, R.B.; Yoshino, T.; Yao, Z.; Ebi, H. Response to Anti-EGFR Therapy in Patients with BRAF non-V600-Mutant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 7089–7097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarova, L.; Kleiblova, P.; Janatova, M.; Soukupova, J.; Zemankova, P.; Macurek, L.; Kleibl, Z. CHEK2 Germline Variants in Cancer Predisposition: Stalemate Rather than Checkmate. Cells. 2020, 9, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulski, C.; Wokołorczyk, D.; Jakubowska, A.; Huzarski, T.; Byrski, T.; Gronwald, J.; Masojć, B.; Deebniak, T.; Górski, B.; Blecharz, P.; Narod, S.A.; Lubiński, J. Risk of breast cancer in women with a CHEK2 mutation with and without a family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29, 3747–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.F.; Guo, C.L.; Liu, L.H. The effect of CHEK2 variant I157T on cancer susceptibility: evidence from a meta-analysis. DNA Cell Biol. 2013, 32, 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonen, R.A.C.M.; Wiegant, W.W.; Celosse, N.; Vroling, B.; Heijl, S.; Kote-Jarai, Z.; Mijuskovic, M.; Cristea, S.; Solleveld-Westerink, N.; van Wezel, T.; Beerenwinkel, N.; Eeles, R.; Devilee, P.; Vreeswijk, M.P.G.; Marra, G.; van Attikum, H. Functional Analysis Identifies Damaging CHEK2 Missense Variants Associated with Increased Cancer Risk. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiloh, Y. ATM and ATR: networking cellular responses to DNA damage. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001, 11, 71–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen, B.; Tuxen, I.V.; Yde, C.W.; Gabrielaite, M.; Torp, M.H.; Kinalis, S.; Oestrup, O.; Rohrberg, K.; Spangaard, I.; Santoni-Rugiu, E.; Wadt, K.; Mau-Sorensen, M.; Lassen, U.; Nielsen, F.C. High frequency of pathogenic germline variants within homologous recombination repair in patients with advanced cancer. NPJ Genom Med. 2019, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchini, C.; Bibeau, F.; Ligtenberg, M.J.L.; Singh, N.; Nottegar, A.; Bosse, T.; Miller. R.; Riaz, N.; Douillard, J.Y.; Andre, F.; Scarpa, A. ESMO recommendations on microsatellite instability testing for immunotherapy in cancer, and its relationship with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden: a systematic review-based approach. Ann Oncol. 2019, 30, 1232-1243. [CrossRef]

- Umar, A.; Boland, C.R.; Terdiman, J.P.; Syngal, S.; de la Chapelle, A.; Rüschoff, J.; Fishel, R.; Lindor, N.M.; Burgart, L.J.; Hamelin, R.; Hamilton, S.R.; Hiatt, R.A.; Jass, J.; Lindblom, A.; Lynch, H.T.; Peltomaki, P.; Ramsey, S.D.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; Vasen, H.F.; Hawk, E.T.; Barrett, J.C.; Freedman, A.N.; Srivastava, S. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004, 18, 261–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.re3 |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).