2.1. Environmental Assessment of Smelting Technology in the Converter Shop of JSC "Qarmet"

The study analysed emissions from the steel production process in the converter shop. The share of emissions from the total volume in the industry is 1.45% for dust, 6% for carbon monoxide (CO), 0.45% for sulfur dioxide (SO2) and 0.5% for nitrogen oxides (NOx).

The specific output of converter gases is 70–90 m3/t of steel, and the specific dust emission varies from 21–32 kg/t for smelters cooled by scrap metal. The average dust concentration in converter gases is 150–350 g/m3, reaching 1,500 g/m3when additives are added.

The chemical composition of the dust released from the converter bath is shown in

Table 1.

Sulfur enters the converter gases in the form of SO2, and its amount depends on the sulfur content in the metal charge and slag-forming agents. Up to 14% of the sulfur contained in the charge is carried away with converter gases, of which 1% of the sulfur passes into the gas phase, and the rest is adsorbed by converter dust.

Nitrogen oxides are not formed practically in the converter itself; they are formed when working with the afterburning of converter gases in a boiler, where their concentration is approximately 100 mg / m³ (the specific NOx yield is 50 grams / ton of steel). When working without the afterburner, NOx forms by burning gas in a candle at a rate of up to 30 grams per ton of steel. A significant part of emissions are unregulated emissions, which are brief but intense.

A total of 0.03–0.09 kg of dust per ton of steel is formed in the charge yard, 0.04–0.06 kg/t is formed on the bulk feed path, 0.42–0.88 kg/t is formed in the mixing compartment, 0.01–0.02 kg/t is formed in the bucket drying and repair department, and 0.003 kg/t is formed in the ferroalloy preparation area; at the casting site, 0.1–0.12 kg/ton. Unorganized emissions are characterized by a wide range of chemical and dispersed dust compositions.

When cast iron is poured, graphite dust is released with a plate size of 50–100 microns and an iron-containing particle size of 1–80 microns. When oiled scrap is loaded into the converter, polycyclic hydrocarbons are released, and in the presence of zinc and lead, vapours of these metals and their oxides are released. The concentration of organic compounds in gases when using oiled scrap is 60 mg/m3 or 5–6 kg/ton of charge.

During casting, emissions are associated with the decarburization process in cast iron by sucking air into the bath with a jet of poured metal. During periods of steel discharge, fine dust is released, and when bulk materials are poured, coarse dust of 5–200 microns or more is released. The dust content of the air near the dumping sites ranges from 1–100 mg/m3. The specific dust yield during casting ranges from 0.07 to 0.9 kg/ton of cast iron, with an average of 0.16 kg/ton of cast iron.

In the process of steel production, the specific dust yield is 0.02-0.34 kg/t, with an average of 0.09 kg/t steel. The dust consists of 70–75% iron oxides. When additives are added to the bucket, dust emissions increase to 3–5 g/m3, and the average dust content is 0.5–1.5 g/m3. The gas released from the neck of the converter contains approximately 5–10–3% sulfur oxide, a small amount of nitrogen oxide (up to 0.03 g/m3), a moisture content with a pure oxygen blast of 3–5 g/m3, and dust of 150–350 g/m3. The gases are cooled and cleaned of dust in the exhaust duct. The gas path consists of a cooling boiler, a gas purification apparatus, a supercharger and a spark plug.

The work of the tract in cleaning without afterburning CO can be divided into three periods. In the first minutes of purging, air is sucked through the gap between the path and the converter, ensuring complete combustion of CO. Combustion products and air nitrogen form a "tampon" between the evacuated air and CO, which ensures the explosion safety of the system. After the gap is closed with a movable caisson, work is performed without afterburning the gas. At the end of melting, the movable caisson is lifted, and the CO is reignited in the cavity of the converter. The amount of melted dust formed is related to the design of the tuyere, the fractional composition and quality of the fluxing additives, and the temperature of the bath. The methods of combating dust formation include cooling the reaction zone and foaming the slag.

CO emissions during the process without afterburning gases are associated with the fact that at the beginning and end of the purge, the concentration of CO in the converter gases is less than that at which it can burn.

Unorganized emissions are characterized by a wide range of chemical and dispersed dust compositions. There are two trends in solving the problem of preventing environmental pollution by unorganized emissions: the creation of containment and cleaning systems and the improvement of operational technologies, particularly the use of dust suppression agents.

The bulk of the gases in converter production pass through gas purification, where they are cleaned of dust with an efficiency of approximately 89–95%.

2.2. Investigation of Dust and Gas Release During the Oxidative Refining of Phosphorous Cast Iron

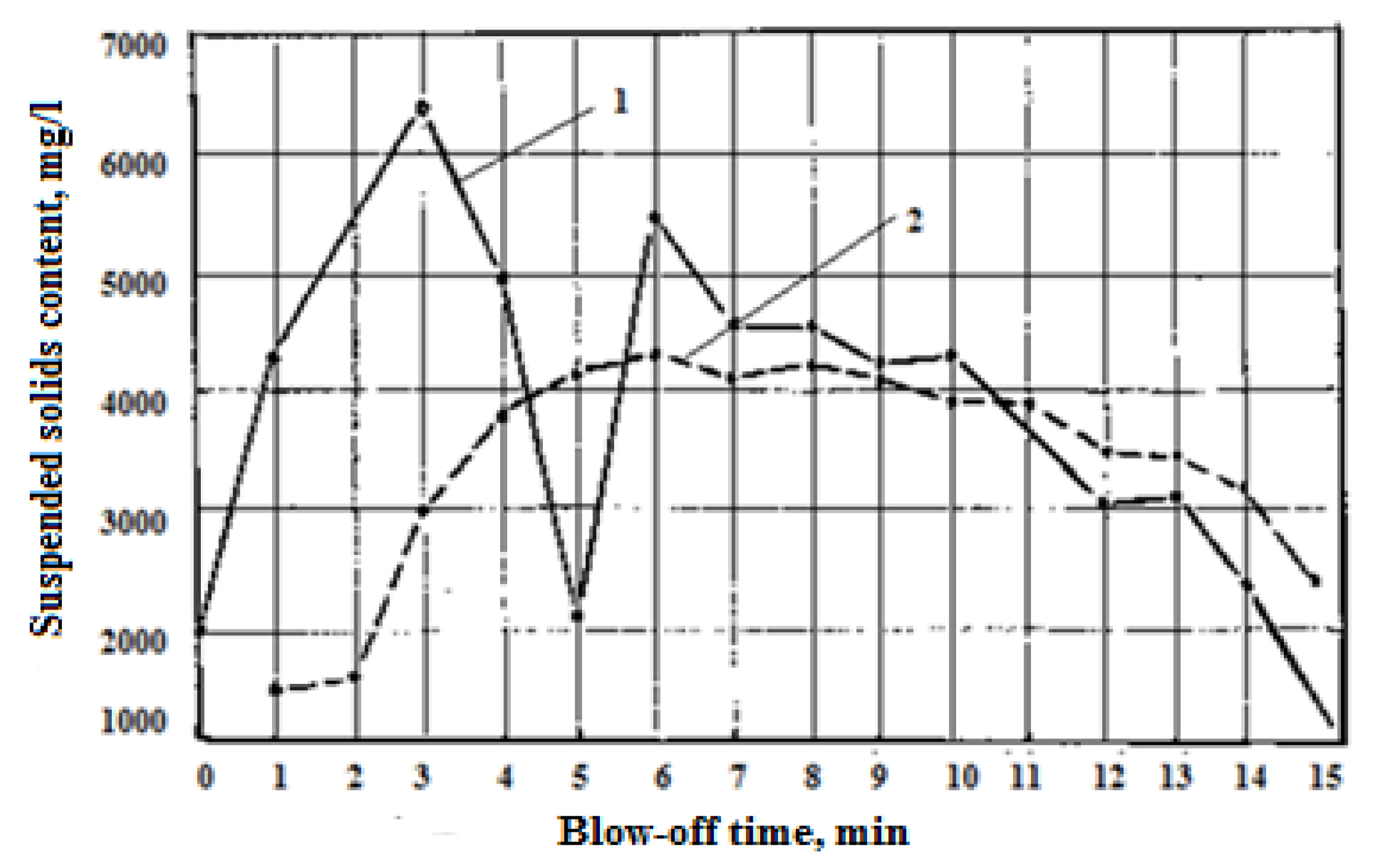

The process of gas release during purging is characterized by the presence of a uniform area in the middle part of the melting process, as well as an increasing intensity of the process at the beginning and a sharp decrease at the end of melting. The supply of fluxing additives leads to bursts of gas emissions.

The measurements revealed that 0.173 tons of dust or 0.57 kg per ton of steel is released through the candle during melting. During purging, 0.53 kg of dust is emitted per ton of steel and 8.32 kg/ton of CO. Measurements of the dust content of exhaust gases on the candle revealed that the amount of dust during purging varies widely, and to assess the effects of technological parameters, the slag water used for gas purification is taken.

An analysis of the measurements revealed that the nature of dust emissions from the candle correlates with the content of suspended particles in the water of the solivor (the last stage of gas purification). This made it possible to find a closer relationship between the technological parameters and the formation and emission of dust (

Figure 1).

An analysis of the results revealed that, owing to significant fluctuations in water consumption for gas purification from smelting to smelting, there was a certain variation in the quality of the charge materials. It is impossible to provide an accurate quantitative description of each melting.

However, a qualitative assessment of the data obtained allows us to reliably show the influence of various technology parameters on the nature of dust release from the converter zone and, consequently, its emissions into the atmosphere. As is known from the literature data, as well as gas analysis data, the initial purge period is characterized by an increase in gas emission.

Similarly, the amount of dust emitted increases. In smelters with partial or complete slag abandonment, judging from the content of suspended particles in the water, the amount of emitted dust is lower and the increase in dust emissions is slower and more stable without peak spikes, which worsen the operation of gas purification (

Figure 2).

During the established intensive decarbonisation process, the content of suspended particles in the solivor water is dependent on the intensity of purging; however, this dependence is characteristic of only the purging period between bulk additives.

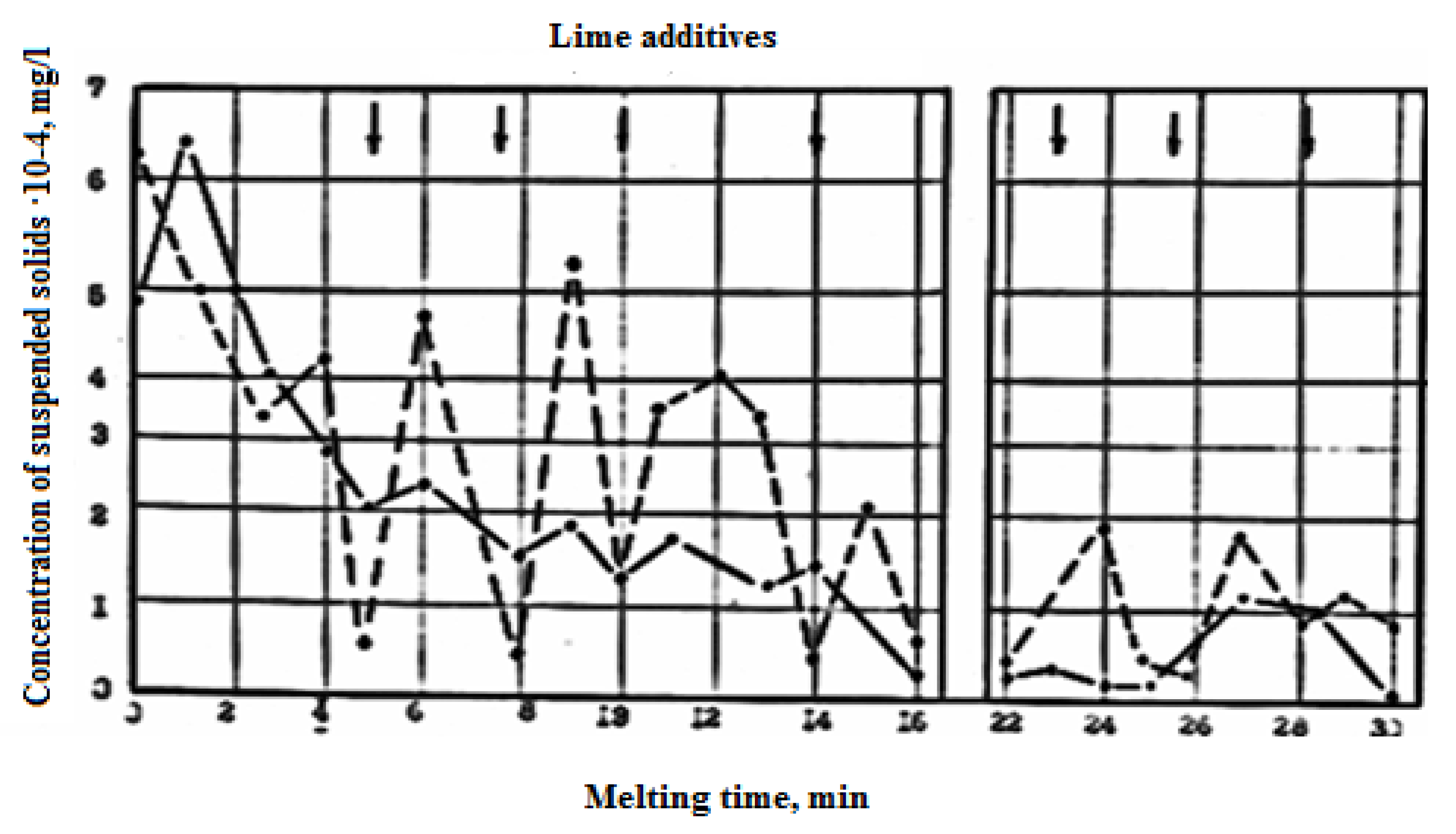

The process of dust extraction directly depends on the mode of addition of the bulk slag-forming materials. During the period of intensive decarbonization, each portion of these materials leads to a significant increase in gas emission, causing peak dust emissions from the converter. This phenomenon is clearly reflected by the content of salts suspended in the water, as shown in

Figure 3. These peak spikes worsen the operation of gas purification and lead to the appearance of disorganized emissions.

Leaving the final slag in the converter promotes the rapid formation of easily mobile foamy slag after the addition of cast iron and starting purging. This slag acts as a filter, absorbing dust and binding it to the calcium oxides in the slag melt. The more intensive start of the refining process is due to the physical heat of the final slag. The presence of iron oxide in the slag melt reduces the oxidation of iron and its removal during gas treatment.

Peak dust emissions during advanced decarburization and lime delivery are associated with a sharp increase in the volume of exhaust gases due to an increase in the yield of CO and CO2 from the decomposition of lime scale carbonates and additional CO formation from the acceleration of the reaction of carbon and oxygen on the finished nuclei, which are the rough surfaces of embedded lime.

An increase in the volume of gases in the converter leads to an increase in the rate of gas outflow, which violates the conditions for lime particles to enter the converter. When the gas velocity reaches 35–40 m/s, lime particles less than 8–10 mm in size begin to be removed from the converter.

The analysis of the gas release during the lime supply to the bath, described by the system of equations (1) and (2), allows us to determine the parameters for controlling the dust and gas emission process from the converter bath.

where О

2g - the total oxygen consumption through the tuyere;

О2k - oxygen consumption with oxygen-containing additives;

К1, К2 - specific gas emission per 1 m3 supplied with an oxygen blast and with oxygen-containing additives;

Vg - the output of gaseous goring products;

Н2О, Н2 - the output of water vapour and hydrogen;

CO, CO

2 - the output of CO and CO

2 from the decomposition of lime scale.

where

- is the weight of the portion of lime supplied, kg;

A - percentage of underlime, %;

N - the loss during calcination, %.

On the basis of the data obtained, a new regime for the supply of bulk materials has been developed, the essence of which is to maintain the volume of exhaust gases at a level not exceeding the capacity of the exhaust duct and the performance of the smoke pump.

Studies have shown that a reduction in the volume of exhaust gases during the supply of bulk materials is achieved by reducing the purge intensity to 0.5-0.7 of its nominal value. To maintain the high productivity of the process, the purge intensity must be increased to the initial level after the bulk materials are supplied.

The decarburization process and the associated CO yield do not decrease immediately after the purge intensity decreases because of the inertia of the process, but after a while. It is recommended to supply bulk materials after a short exposure and increase the purging intensity to the initial level after a short exposure.

The time interval between reducing the purge intensity before feeding bulk materials and increasing the intensity after feeding depends on the CO content in the exhaust gases determined by gas analysis. The best results are achieved if the following conditions are met: the interval for anticipating a decrease in purging intensity before feeding and the interval for delaying an increase in intensity after feeding should be 0.8–1.0:0.3–0.1 relative to the CO content in the exhaust gases, expressed as a percentage.

The developed mode completely eliminates the ejection of gases from under the converter's "skirt" and reduces dust removal into the exhaust duct and gas purification by 2.5-3.3 times. When the converter is operated with an afterburning system on phosphorous cast iron, CO emissions are observed in the second melting period due to low CO concentrations (below the ignition limits of wet gases <35%), as are increased CO emissions at the initial moments of purging. This is due to the low rate of increase in the CO concentration to the ignition limits, which leads to a forced release of CO into the atmosphere at 9.3 m3/t of steel, as well as a low decarburization rate and CO release during the second melting period.

The high specific CO emissions are explained by the presence of wet converter gas purification systems and the technology of a two-slag purge process. Increased

The humidity of the converter gases does not allow for afterburning on the "candle" during the initial purge period until the CO concentration reaches the ignition limit.

To increase the CO yield, a gas-dynamic method of CO accumulation in the exhaust duct is proposed. Reducing the dilution of exhaust gases under the "skirt" with air is achieved by reducing the productivity of the flue pump and increasing oxygen consumption during the initial purge period, followed by a decrease and increase in flue pump performance at the beginning of exhaust gases and active decarbonisation. This technique reduces CO emissions to 7.6 m3/t.

The interruption of purging and the dumping of the converter for intermediate loading of slag do not allow organizing afterburning of CO. However, the organization of melting with a shortened first period and a carbon content of 0.8–1.0% on the landfill allows for afterburning of CO before release into the atmosphere and reducing emissions from 21.1–15.6 m3/ton of steel. An increase in the carbon content ensures that the second period is more "hot", reduces heat loss and increases the temperature of the melt at the outlet.

During a series of experiments in which the purge intensity was increased to the range of 1000-1100 nm3/min and the flue pump capacity was reduced to 110 thousand m3/h, it was possible to reduce the time to reach the CO concentration corresponding to the limit ignition. This made it possible to reduce CO emissions by 7.6 m3/t of steel.

The smelting, carried out with a shortened first purge period and converter rolling at a carbon content in the metal of 0.9–1.0%, contributed to an increase in the rate of decarbonization and an increase in the concentration of CO in the exhaust gases of the second purge period to 35% or more. This made it possible to organize afterburning the SO on the "candles" of converters.

The introduction of this technology not only reduced CO emissions into the atmosphere but also reduced heat losses during intermediate dumping and provided a more complete use of the chemical potential of liquid cast iron in the second melting period, allowing for deeper dephosphoration and desulfurization while reducing the total oxygen consumption to 1870 m3/melt on average.

The analysis of unorganized emissions from under the movable "skirt" of the converter and through the lantern of the main building of the workshop reveals a discrepancy between the volume of polluted gases released from the converter, the capacity of the exhaust duct and the gas cleaning equipment. This is due to the need to increase steel production, which is solved by increasing the converter tank and the intensity of purging the bath with oxygen without reconstructing the exhaust duct.

The operation of converters with an enlarged tank not only worsens environmental performance but also reveals a number of disadvantages that reduce the safety of equipment operation and smelting technology. Thus, an increase in the converter tank increases the thermal load on the boiler.

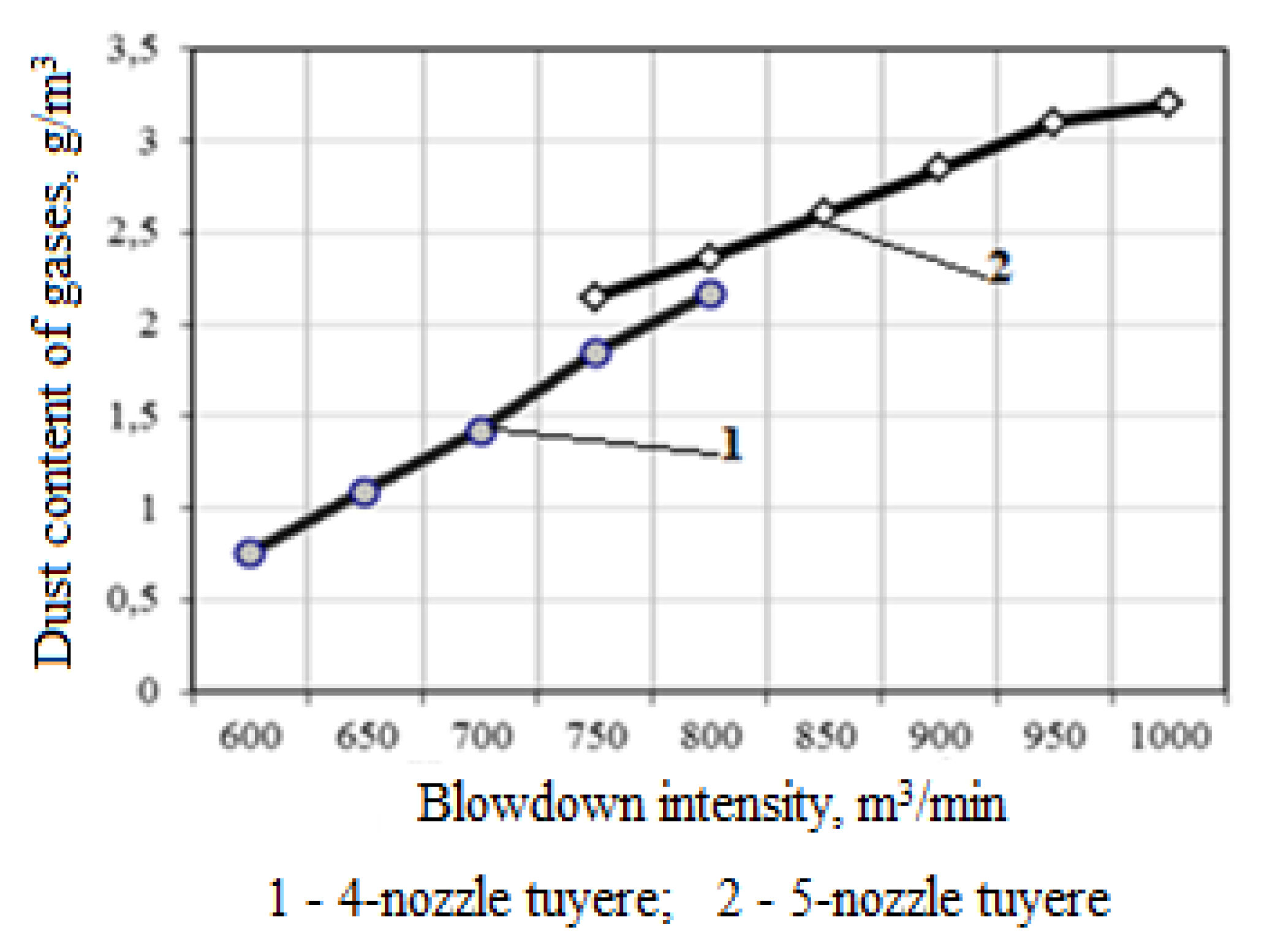

To adjust the volume of exhaust gas and the throughput of the path, conversion technology with a reduced tank (300–320 versus 360–365 tons) was introduced in combination with a reduction in the purging intensity (600–800 m3/min versus 800–950 m3/min) of the oxygen converter bath.

The reduced intensity of purging through the four-needle tuyere significantly reduces dust emission by 30–40% (

Figure 4), which also leads to a reduction in sludge output from gas cleaners (

Table 2). Bringing the volume of gases released from the converter bath in line with the throughput of the exhaust duct by reducing the intensity of purging and reducing the tank reduces unorganized emissions from under the "skirt" of the converter from 136 to 22.7 kg/ton of steel produced, that is, by 83.4%.

To ensure the required level of slag formation and blast purging mode while improving the environmental performance of the process, the bath was switched to purging with a four-cycle oxygen lance and a new dynamic purging mode. Experimental smelting carried out via a single-slag process with a phosphorus content of less than 0.4% and a double-slag process with a phosphorus content of more than 0.4% shows that lowering the converter tank from 365 to 320 tons reduces dust removal from the converter, regardless of the tuyere design, by 15-25%.

In addition to improving environmental performance, technological, technical and economic indicators of converter smelting are increasing: reducing slag oxidation by 1.7-2.0%; reducing the proportion of smelts with emissions by 3.4-6.6%, with blowouts of 7-8%; reducing cast iron consumption by 2.5-3.9 kg/t; and increasing the yield by 0.5%.

Purging the bath with reduced intensity ensures rapid ignition of the melting and an early start of the decarburization process.

The number of disorganized emissions is also affected by the structural elements of the movable skirt in its upper position. To reduce

A new design of the device was developed and implemented for unorganized emissions and complete capture of exhaust gases in the upper position of the movable "skirt" when casting iron, filling scrap and at the initial moment of purging until the melting "ignites" and lowering the "skirt" to the lowest position.

To increase the reliability of the seal between the hood and the "skirt" in its upper position, as well as to increase the resistance of metal structures in the area of the converter neck and prevent gases from escaping, a water-cooled cylindrical device with a horizontal visor in the upper part was installed coaxially with the vertical axis of the converter. The edge of the visor is flanged and directed downwards. A cylindrical sealing gate is installed on the horizontal part of the movable "skirt" opposite the flanging of the apron. In the upper position of the "skirt", the flanging of the apron fits tightly into the sand gate of the "skirt", preventing the escape of gases and ensuring their complete capture.

The introduction of this device has made it possible to reduce the volume of unorganized dust emissions through the lantern of the main building of the workshop by 300 tons per year.

2.3. Effects of Phosphorus Concentration in Processed Pig Iron on Environmental Indicators of Oxidative Refining

However, the key solution to the problem of improving the environmental safety of metallurgical production, including converter production, which is aimed primarily at increasing the competitiveness of the plant's metal products on the world market, is the transition to the use of rich iron ore raw materials with a low phosphorus content.

The studies conducted during the development of the technology of processing cast iron with a reduced phosphorus content allowed us to determine the optimal technological methods for achieving high technical and economic environmental indicators, depending on the phosphorus content in the processed cast iron.

When processing cast iron with a phosphorus content of 0.3–0.6% via a single-slag process, low costs of cast iron, lime and gross emissions of dust and CO are achieved; however, the process does not provide metals with low concentrations of phosphorus and sulfur at the outlet.

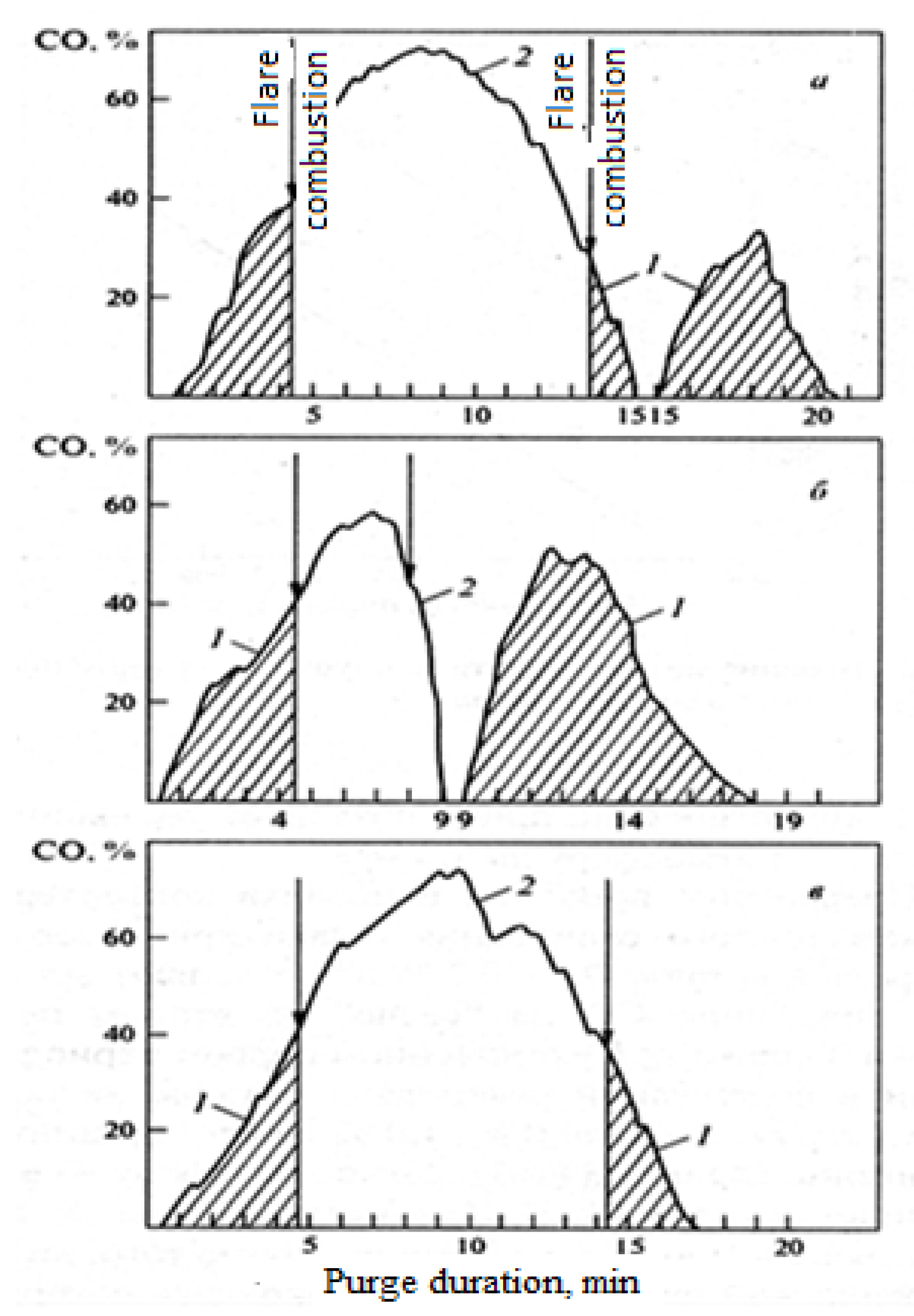

On the other hand, the processing of pig iron with a phosphorus content of less than 0.3% via the technology with early loading of intermediate slag did not significantly improve the technological performance of the process but only worsened the environmental performance due to increased CO and dust emissions associated with additional dust emissions during the collapse of the converter compared with the single-slag process and the impossibility of complete afterburning of CO on the "candle" before being released into the atmosphere due to the interruption of the process at maximum CO formation (

Figure 5). Research on technical and economic indicators, as well as. The environmental characteristics of various cast iron processing methods, including the single-slag process A, with early removal of intermediate slag B and the traditional double-slag process C, revealed that the most effective and environmentally friendly process is the use of a single-slag process with a phosphorus content of no more than 0.3% in the cast iron (

Table 3).

When processing cast iron with a high phosphorus content (more than 0.3%), as well as silicon (more than 1.0%) and sulfur (more than 0.03%), to achieve low end values of phosphorus and sulfur, it is necessary to carry out a process with early removal of acid slag by 7–9 minutes of purging. This method leads to increased emissions of dust and carbon monoxide (

Table 3). Moreover, carbon monoxide emissions are even higher than those in the traditional two-slag purging process, that is, intermediate slag is removed after 65–75% of the main purging time. This occurred because the interruption of the purging process occurred at the maximum concentration of carbon monoxide (40–60%), and it was not possible to ensure safety after the resumption of purging (

Figure 5b).

The duration of the afterburning period of carbon monoxide on a candle before being released into the atmosphere is significantly reduced, and the majority of carbon monoxide enters the atmosphere without afterburning.

During experimental smelting via method A, low amounts of dust emissions (0.305 t/melt) and carbon monoxide (2,808 t/melt) and low consumption rates of lime (71.8 kg/t) and oxygen (63.4 m3/t) were recorded.

In addition, there was a decrease in the oxidation of slag to 20.7% and a high percentage of the yield of usable metal - 89.6%.

When developing the technology for processing low-phosphorus cast iron, all environmentally friendly modes of converter smelting, which were developed for processing pig iron with high phosphorus content, have been considered.

The resource-saving technology of converter melting involves leaving the slag from the previous melting in an inactive state. For this purpose, lime or dolomite additives are used, as are preprepared steelmaking slag, which accounts for 20–30% of the total lime consumed for melting.

Lime is added in the process of purging in portions of 2 tons. Thirty to forty seconds before the additive, the purge intensity decreases by 150–200 m3/min, after which it increases to the previous level.

Purging of the bath is carried out with reduced intensity via a specially designed dynamic mode. During the first 3–5 min, purging was carried out at an intensity of 850-900 m3/min, and then the intensity decreased to 650–750 m3/min during the main purging time.

In the final stage, purging is carried out with a decrease in the tuyere position to 1.3–1.5 m and an increase in the purging intensity to 850–900 m3/min.

Reducing the phosphorus content in processed cast iron by 0.3% decreases lime consumption from 143 kg/ton of steel to 77. This allows for the reduction of lime production and decommissioning of some environmentally unfriendly aggregates used in production.

When working with low-phosphorous cast iron, the use of a single-slag process reduces the duration of purging and smelting by 10–16%. This, in turn, improves the performance of converters.