Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

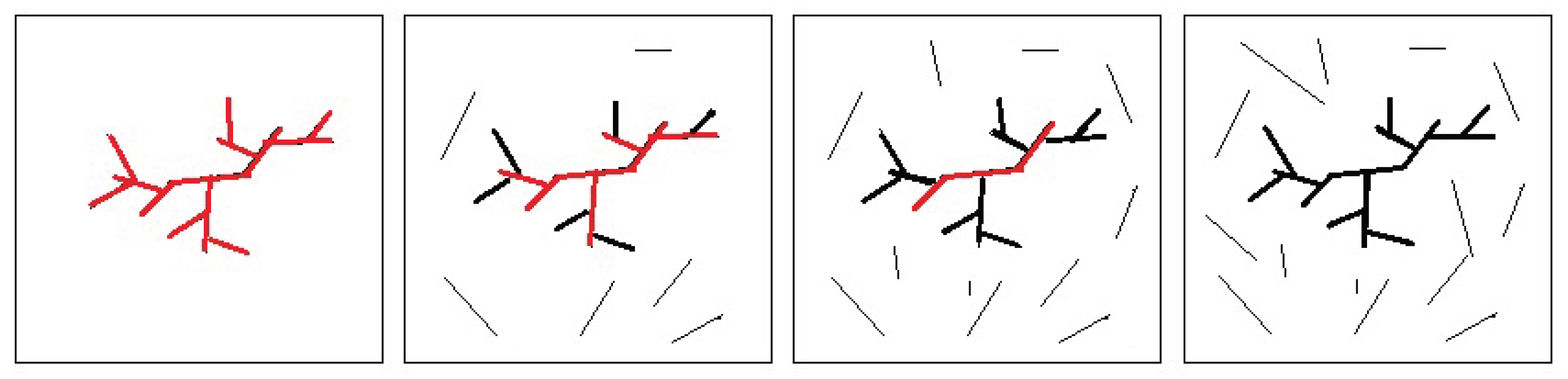

Seismic Activation Fault Dynamics

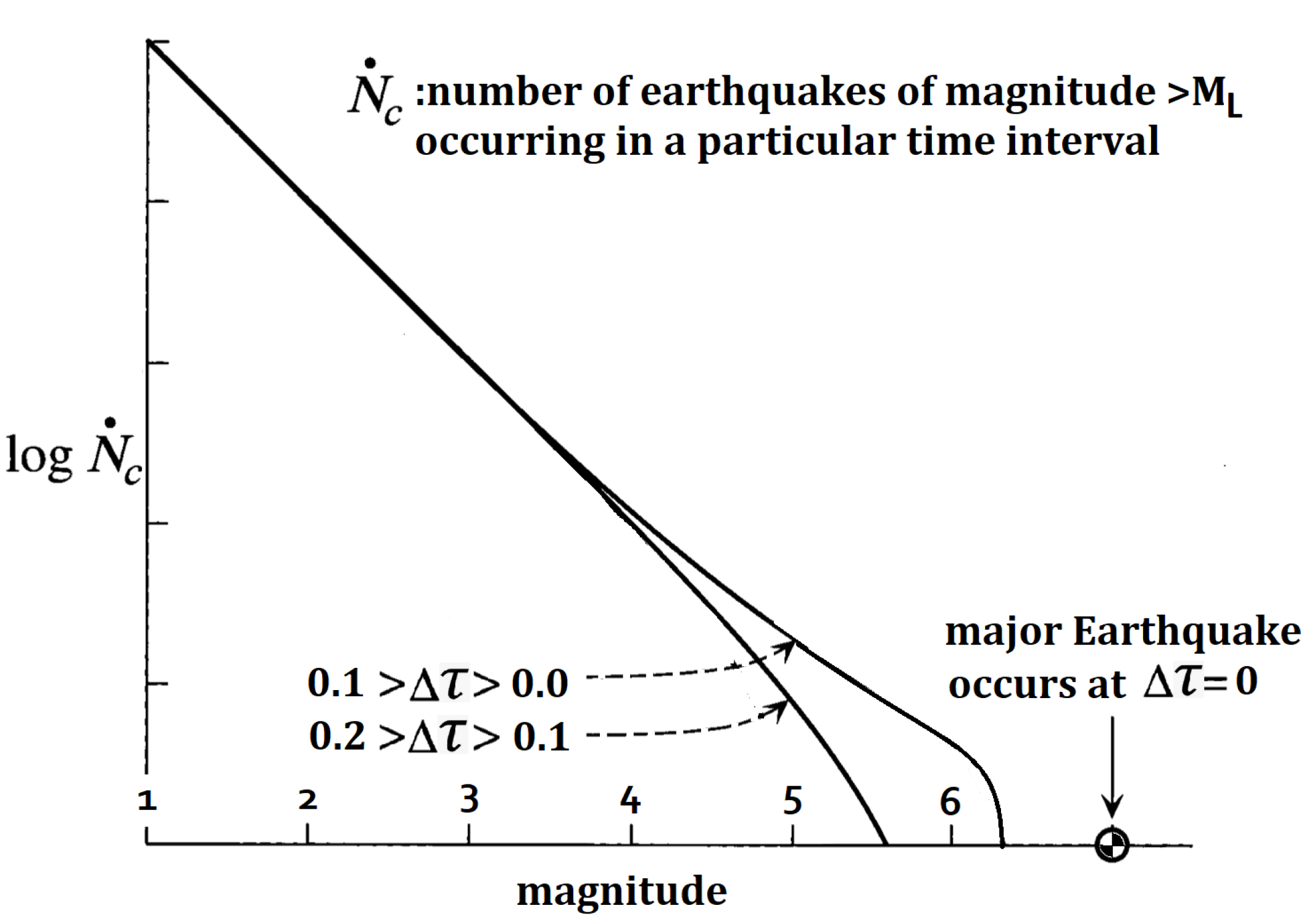

Statistical Physics Critical Scaling Theory

Results

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Bena, I.; Droz, M.; Lipowski, A. Statistical mechanics of equilibrium and nonequilibrium phase transitions: the Yang–Lee formalism. International Journal of Modern Physics B 2005, 19, 4269–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zion, Y. Collective behavior of earthquakes and faults: Continuum-discrete transitions, progressive evolutionary changes, and different dynamic regimes. Reviews of Geophysics 2008, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zion, Y.; Lyakhovsky, V. Accelerated seismic release and related aspects of seismicity patterns on earthquake faults. Earthquake processes: Physical modelling, numerical simulation and data analysis Part II 2002, 2385–2412. [Google Scholar]

- Bindel, D.S. Structured and parameter-dependent eigensolvers for simulation-based design of resonant MEMS Doctoral dissertation. University of California, Berkeley. 2006.

- Bose, M.; Andrews, J.; Hartog, R.; Felizardo, C. Performance and next-generation development of the finite-fault rupture detector (FinDer) within the United StatesWest Coast ShakeAlert warning system. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2023, 113, 648–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.; Ouillon, G.; Sammis, C.; Sornette, A.; Sornette, D. An observational test of the critical earthquake concept. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1998, 103, 24359–24372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broomhead, D.S. ; KingGP Extracting qualitative dynamics from experimental data. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 1986, 20, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykov, V.G. Solitary waves on a crustal fault. Volcanology and Seismology 2001, 22, 651–661. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J.M.; Langer, J.S. Properties of earthquakes generated by fault dynamics. Physical Review Letters 1989, 62, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpentier, D.; Le, D.o.u.s.s.a.l.P. Disordered XY models and Coulomb gases: renormalization via traveling waves. Physical review letters 1998, 81, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C. Accelerating seismicity of moderate-size earthquakes before the 1999 Chi-Chi, Taiwan, earthquake: Testing time-prediction of the self-organizing spinodal model of earthquakes. Geophysical Journal International 2003, 155, F1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S. Fate of the false vacuum: Semiclassical theory. Physical Review D 1977, 15, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cua, G.; Heaton, T. The Virtual Seismologist (VS) method: A Bayesian approach to earthquake early warning. In Earthquake Early Warning Systems, Eds. Gasparini P, Manfredi G, and Zschau J; Springer: Berlin and Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 97–132. [Google Scholar]

- Erdos, L. Random matrices, log-gases and Holder regularity. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1407.5752. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenfeld, N. Continuous Symmetry. In Lectures on phase transitions and the renormalization group; CRC Press, 2018; pp. 335–350.

- Guglielmi, A.V.; Klain, B.I.; Zavyalov, A.D.; Zotov, O.D. A Phenomenological theory of aftershocks following a large earthquake. Journal of Volcanology and Seismology 2021, 15, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardebeck, J.L.; Felzer, K.R.; Michael, A.J. Improved tests reveal that the accelerating moment release hypothesis is statistically insignificant. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasman, A. Glimpses of soliton theory: the algebra and geometry of nonlinear PDEs; American Mathematical Society, 2023.

- Lei, Q.; Sornette, D. Anderson localization and reentrant delocalization of tensorial elastic waves in twodimensional fractured media. Europhys. Letters 2022, 136, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, R.J.; Bostock, M.G.; Peacock, S.M.; Chapman, D.S. Optimal multichannel stretch factors for estimating changes in seismic velocity: Application to the 2012 Mw 7.8 Haida Gwaii earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2023, 113, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskin, M.E. An introduction to quantum field theory. CRC press. 2018.

- Rundle, J.B.; Klein, W.; Turcotte, D.L.; Malamud, B.D. Precursory seismic activation and critical-point phenomena. Microscopic and Macroscopic Simulation: Towards Predictive Modelling of the Earthquake Process 2001, 2165–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Rundle, J.B.; Turcotte, D.L.; Shcherbakov, R.; Klein, W.; Sammis, C. Statistical physics approach to understanding the multiscale dynamics of earthquake fault systems. Reviews of Geophysics 2003, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundle, J.B.; Fox, G.; Donnellan, A.; Ludwig, I.G. Nowcasting earthquakes with QuakeGPT: Methods and first results. In Scientific Investigation of Continental Earthquakes and Relevant Studies; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi, M. FX singular spectrum analysis. In Cspg Cseg Cwls Convention, 392–395.

- Saleur, H.; Sammis, C.; Sornette, D. Renormalization group theory of earthquakes. Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics 1996, 3, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, M. Elastic wave behavior across linear slip interfaces. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1980, 68, 1516–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanis, A.; Vallianatos, F.; Makropoulos, K. Seismic and electrical precursors to the 17-1-1983, M7 Kefallinia earthquake, Greece: Signatures of a SOC system. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Part A: Solid Earth and Geodesy 2000, 25, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianatos, F.; Chatzopoulos, G. A complexity view into the physics of the accelerating seismic release hypothesis: Theoretical principles. Entropy 2018, 20, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianatos, F.; Sammonds, P. Evidence of non-extensive statistical physics of the lithospheric instability approaching the 2004 Sumatran–Andaman and 2011 Honshu mega-earthquakes. Tectonophysics 2004, 590, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.S.; Aki, K. Scattering characteristics of elastic waves by an elastic heterogeneity. Geophysics 1985, 50, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Johnston, S.; Robinson, R.; Vere-Jones, D. Tests of the precursory accelerating moment release model using a synthetic seismicity model for Wellington, New Zealand. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111. [Google Scholar]

| Moment Magnitude | Average Fault Material Displacement (m) | Fault Rupture Length (km) |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0.05 | 1 |

| 5 | 0.15 | 3 |

| 6 | 0.5 | 10 |

| 7 | 1.5 | 30 |

| 8 | 5 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).