Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Reagents and Antibodies

2.3. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.4. Western Blotting

2.5. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.6. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Assay

2.7. Transfection of siRNA or Plasmids

2.8. Colleciton of Ovarian Tissue

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

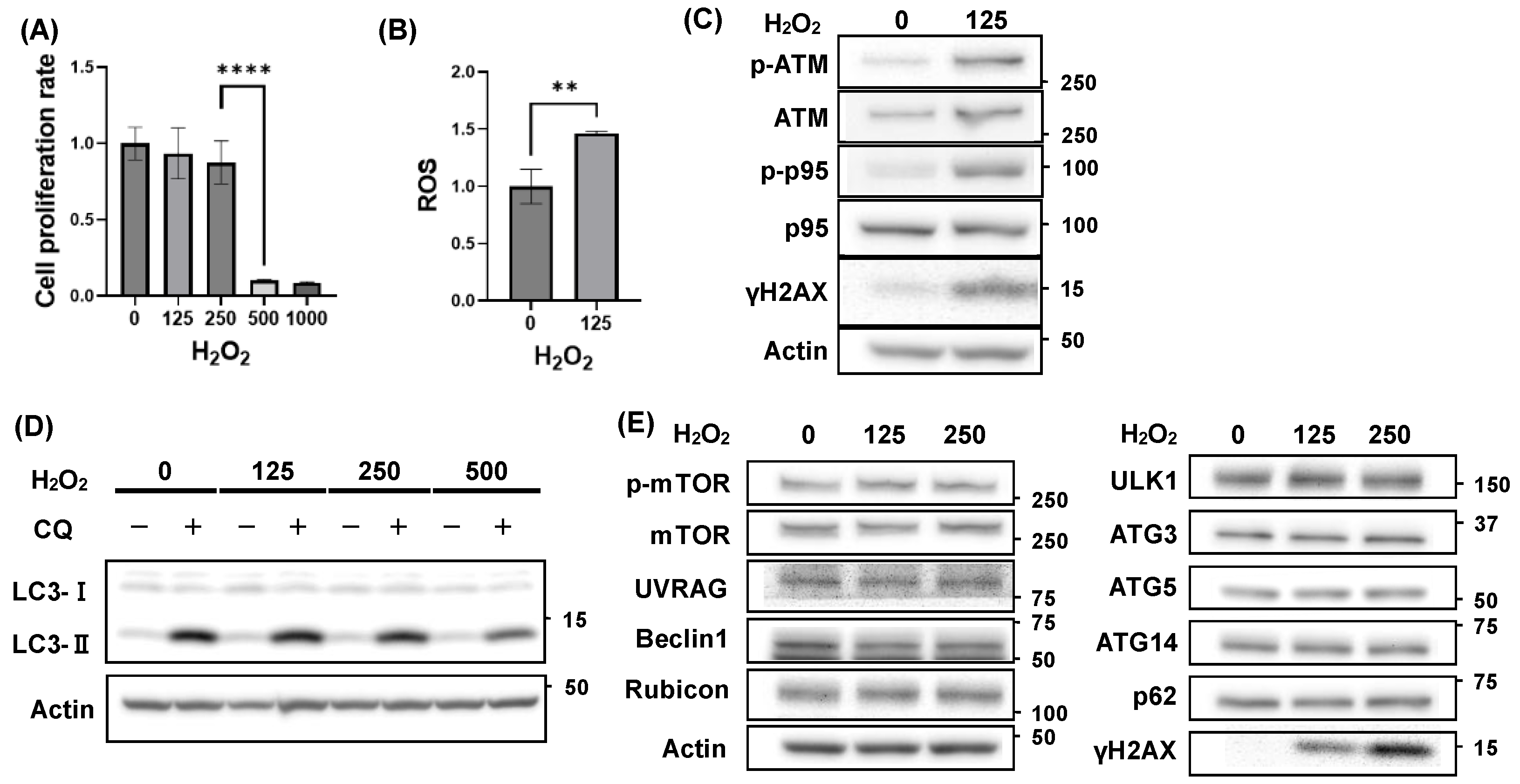

3.1. Autophagy Activity Unaffected by H₂O₂ Treatment

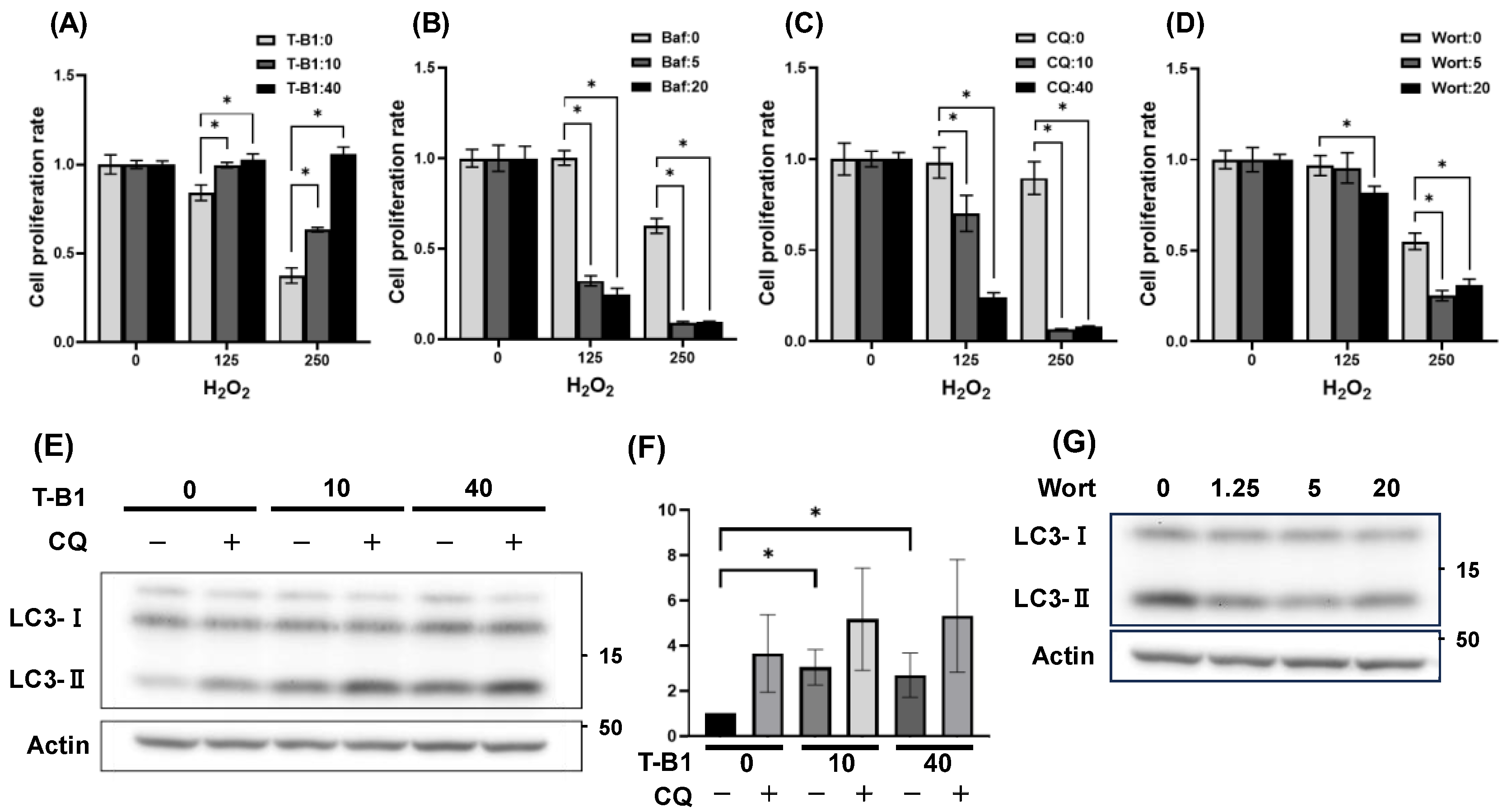

3.2. Autophagic Activation Enhanced HGrC1 Viability Against H₂O₂-Induced Oxidative Stress

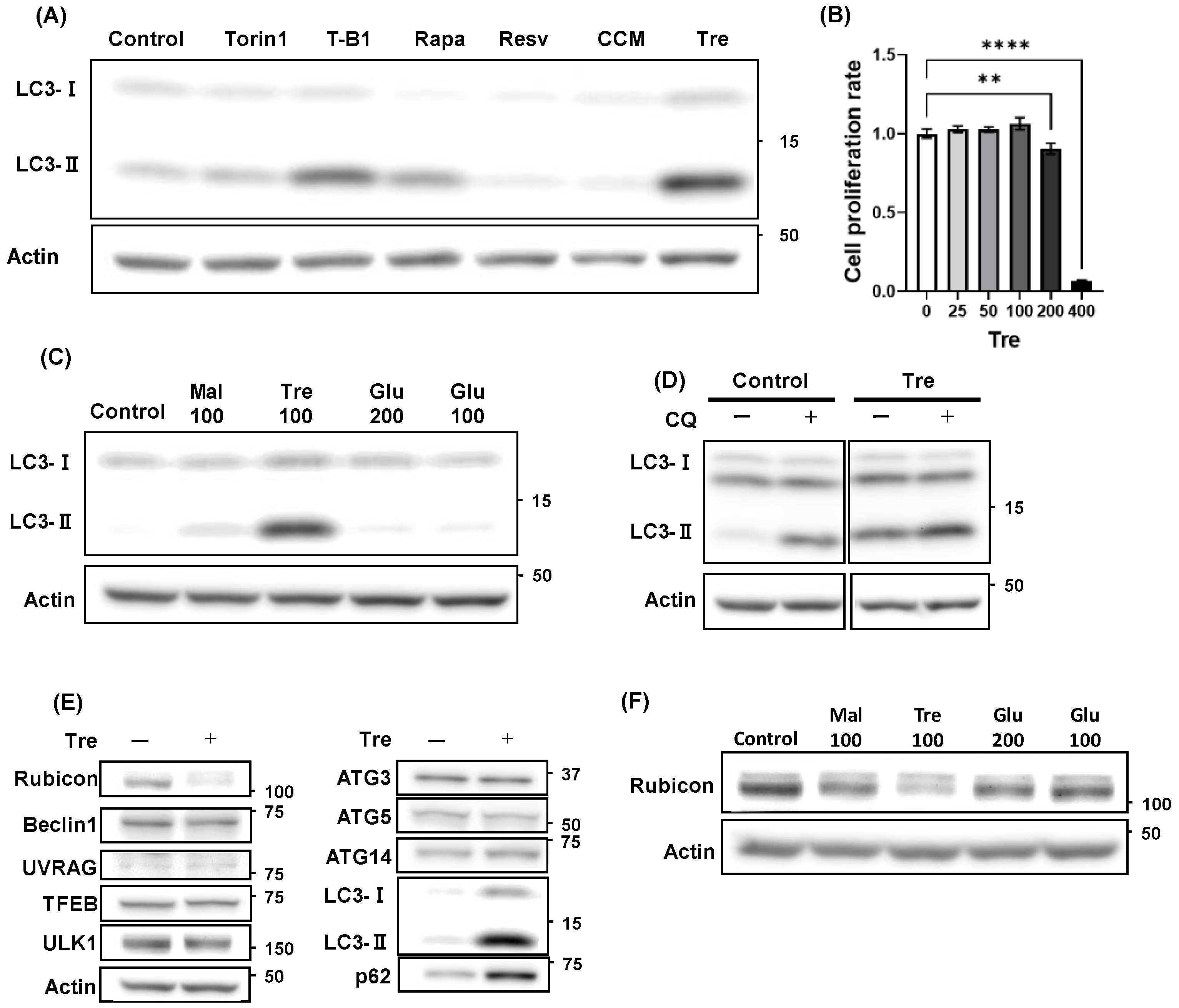

3.3. Trehalose Activated Autophagy and Decreased Rubicon Expression

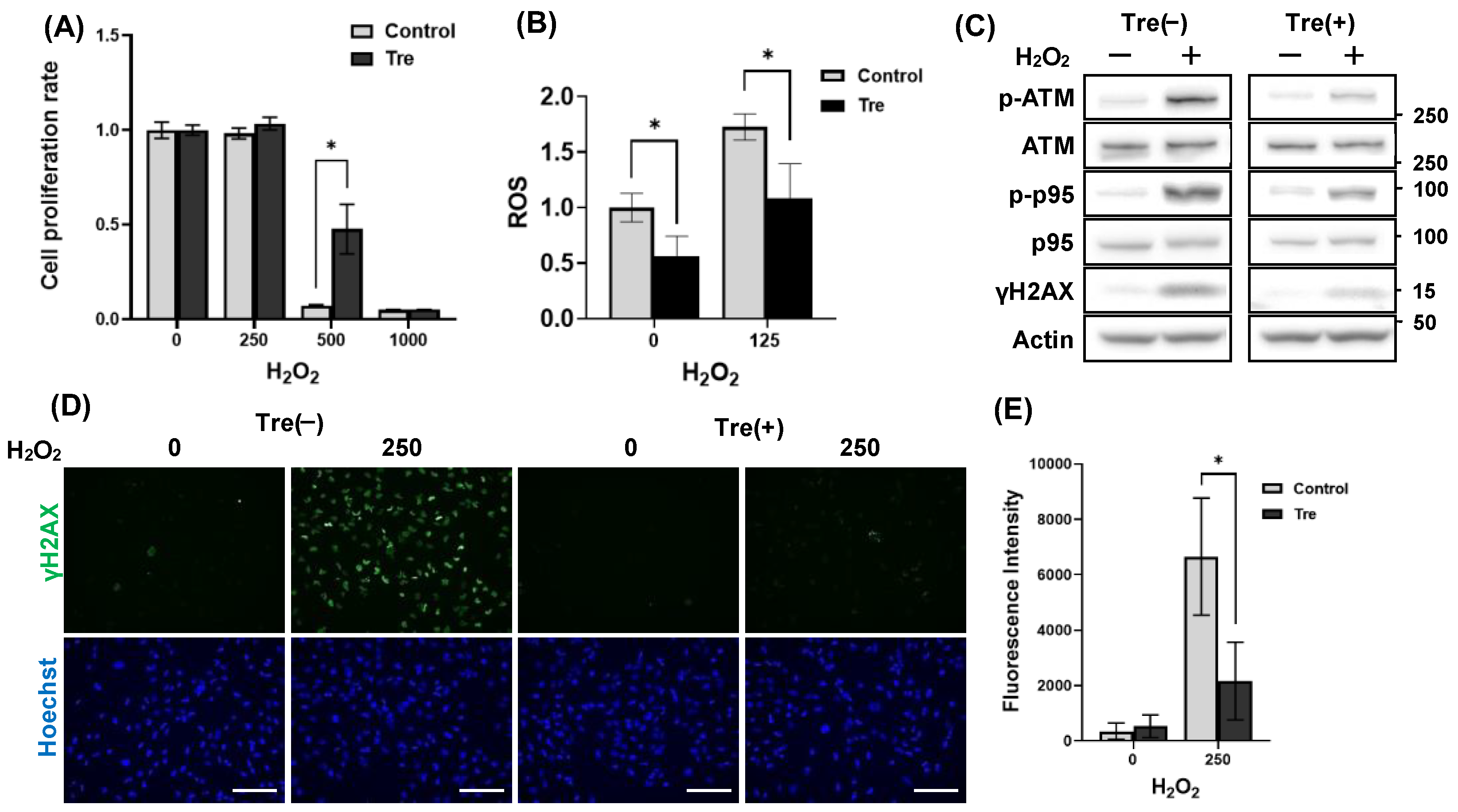

3.4. Trehalose Enhanced Cell Viability Against H₂O₂-Mediated Oxidative Stress

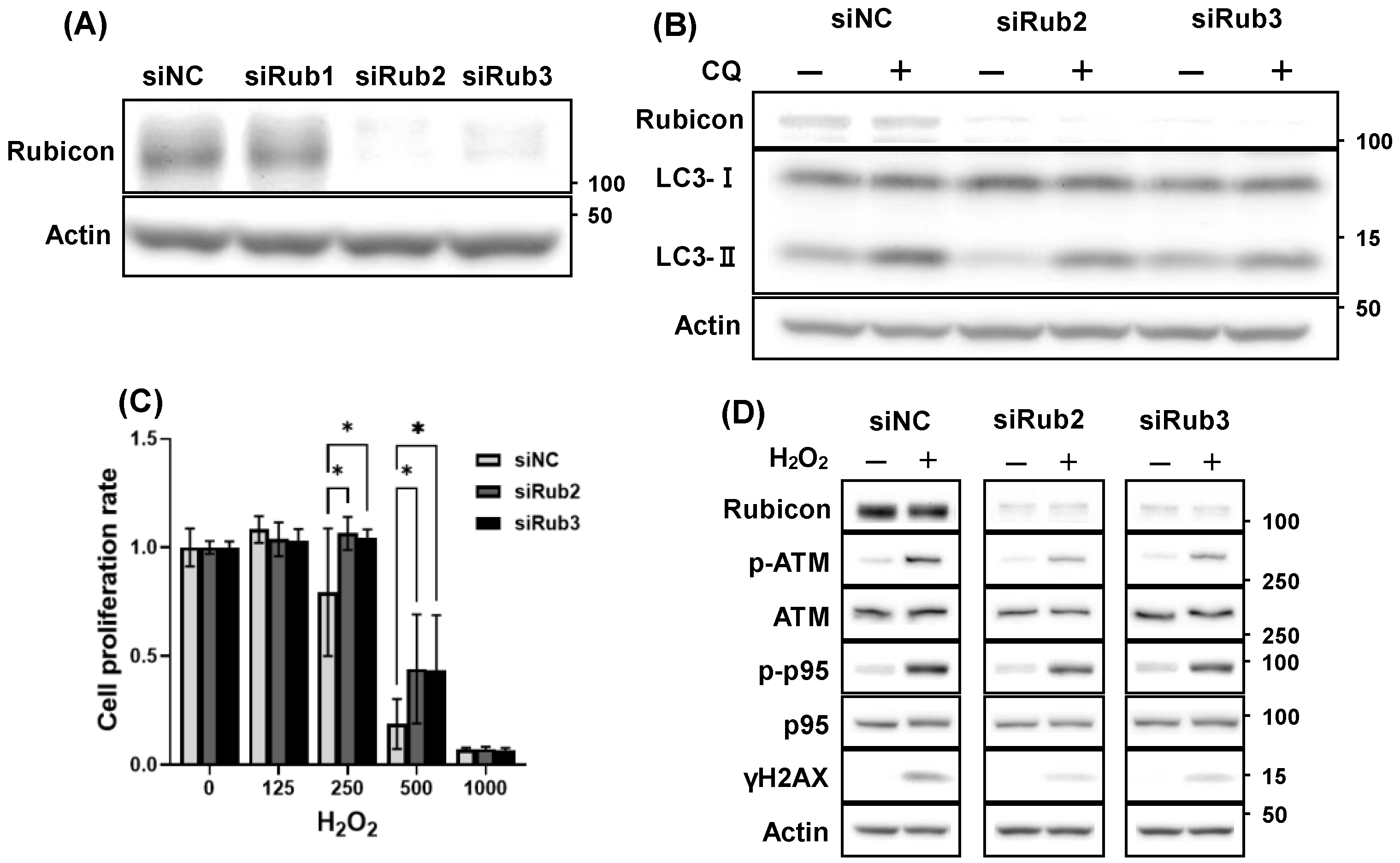

3.5. Decreased Rubicon Expression, but Not Autophagic Activation, Was Involved in Reducing DNA Damage

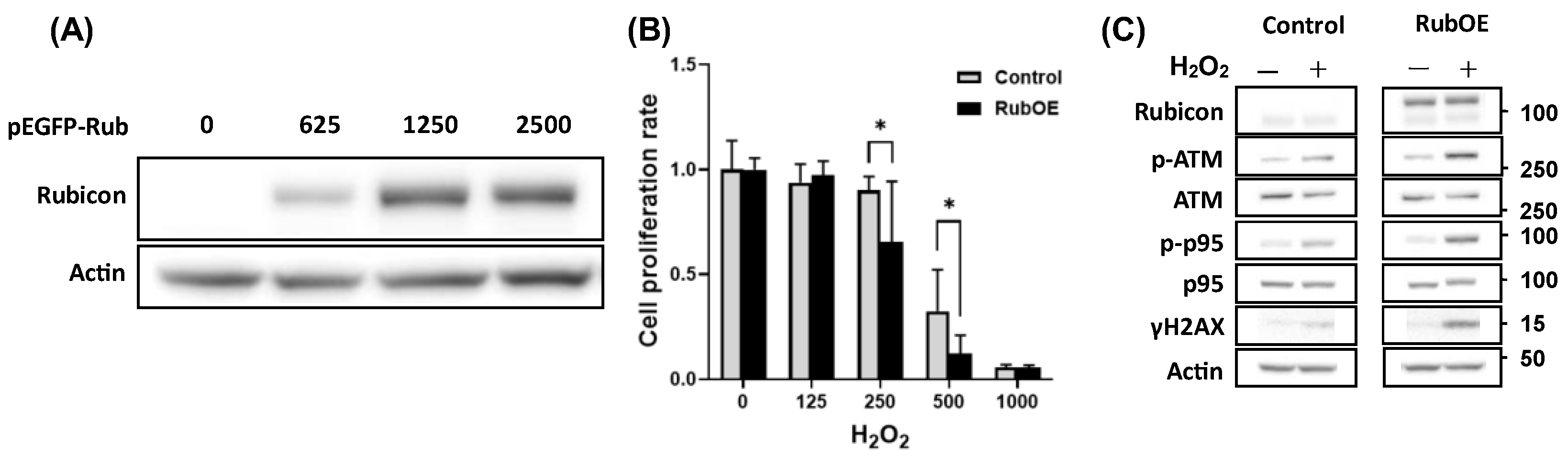

3.6. Increased Rubicon Expression Enhanced DNA Damage in Granulosa Cell Line

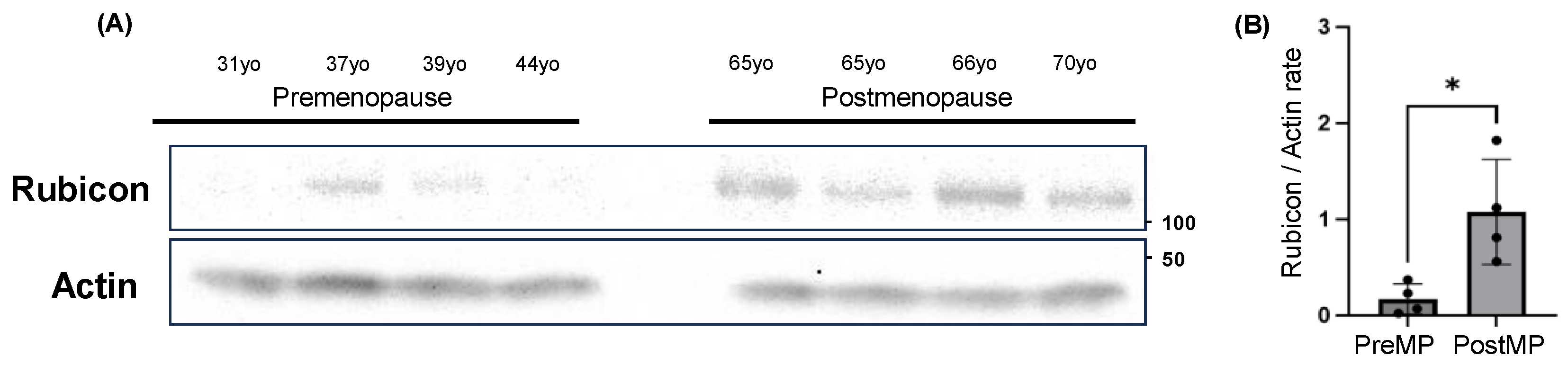

3.7. Increased Rubicon Expression in Ovaries of Postmenopausal Women

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATM | Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated |

| Baf | Bafilomycin A1 |

| CQ | Chloroquine |

| FSH | Follicle-stimulating Hormone |

| FSHR | FSH Receptor |

| GATA4 | GATA-binding protein 4 |

| GCs | Granulosa Cells |

| γH2AX | γH2A histone family member X |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| LC3 | Microtubule Associated Protein 1 Light Chain 3 beta |

| OS | Oxidative Stress |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| POR | Poor Ovarian Response |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| T-B1 | Tat-Beclin1 D11 |

| TFEB | Transcription Factor EB |

| Wort | Wortmannin |

References

- Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Richards, J.S. Identification of a cyclic adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate-response element in the rat aromatase promoter that is required for transcriptional activation in rat granulosa cells and R2C leydig cells. Mol Endocrinol 1994, 8, 1309–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, J.V.; Kristensen, S.G.; Nielsen, M.E.; Humaidan, P.; Dal, Canto, M. ; Fadini, R. LH-receptor gene expression in human granulosa and cumulus cells from antral and preovulatory follicles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012, 97, E1524–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekmans, F.J.; Soules, M.R.; Fauser, B.C. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr Rev 2009, 30, 465–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraretti, A.P. ; La, Marca, A.; Fauser, B.C.; Tarlatzis, B.; Nargund, G.; Gianaroli, L. ESHRE consensus on the definition of 'poor response' to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod, 1616. [Google Scholar]

- Buffenstein, R.; Edrey, Y.H.; Yang, T.; Mele, J. The oxidative stress theory of aging: embattled or invincible? Insights from non-traditional model organisms. Age (Dordr) 2008, 30, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, K.; Park, S.C.; Lee, B.C. Female Reproductive Aging and Oxidative Stress: Mesenchymal Stem Cell Conditioned Medium as a Promising Antioxidant. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immediata, V.; Ronchetti, C.; Spadaro, D.; Cirillo, F.; Levi-Setti, P.E. Oxidative Stress and Human Ovarian Response-From Somatic Ovarian Cells to Oocytes Damage: A Clinical Comprehensive Narrative Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatone, C.; Carbone, M.C.; Falone, S.; Aimola, P.; Giardinelli, A.; Caserta, D. Age-dependent changes in the expression of superoxide dismutases and catalase are associated with ultrastructural modifications in human granulosa cells. Mol Hum Reprod 2006, 12, 655–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, A.; Furuta, A.; Yamada, K.; Yoshida-Kawaguchi, M.; Yamaki-Ushijima, A.; Yasuda, I. The Role of Autophagy in the Female Reproduction System: For Beginners to Experts in This Field. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, S.R.; Kuma, A.; Akashi, T.; Hara, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Kurikawa, Y. Systemic Analysis of Atg5-Null Mice Rescued from Neonatal Lethality by Transgenic ATG5 Expression in Neurons. Dev Cell 2016, 39, 116–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Gao, H.; Yang, F.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, S. FSH Promotes Progesterone Synthesis by Enhancing Autophagy to Accelerate Lipid Droplet Degradation in Porcine Granulosa Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 626927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawriluk, T.R.; Ko, C.; Hong, X.; Christenson, L.K.; Rucker, E.B. Beclin-1 deficiency in the murine ovary results in the reduction of progesterone production to promote preterm labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, E4194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Chen, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Wei, H.; Zhang, R. EPG5 deficiency leads to primary ovarian insufficiency due to WT1 accumulation in mouse granulosa cells. Autophagy 2023, 19, 644–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Yoshino, O.; Ono, Y.; Yamaki-Ushijima, A.; Tanaka, T.; Shima, T. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 enhances gonadotropin-independent follicular development via sphingosine kinase 1. Am J Reprod Immunol 2021, 85, e13374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, A.; Yamanaka-Tatematsu, M.; Fujita, N.; Koizumi, K.; Shima, T.; Yoshida, T. Impaired autophagy by soluble endoglin, under physiological hypoxia in early pregnant period, is involved in poor placentation in preeclampsia. Autophagy 2013, 9, 303–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Yoshino, O.; Nakashima, A.; Ito, M.; Nishio, K.; Ono, Y. Inhibition of autophagy in theca cells induces CYP17A1 and PAI-1 expression via ROS/p38 and JNK signalling during the development of polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2020, 508, 110792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Oba, M.; Suzuki, M.; Takahashi, A.; Yamamuro, T.; Fujiwara, M. Suppression of autophagic activity by Rubicon is a signature of aging. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayasula., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Iwase, A.; Kiyono, T.; Takikawa, S.; Goto, M.; Nakamura, T. Bayasula.; Iwase, A.; Kiyono, T.; Takikawa, S.; Goto, M.; Nakamura, T. Establishment of a human nonluteinized granulosa cell line that transitions from the gonadotropin-independent to the gonadotropin-dependent status. Endocrinology, 2851. [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima, A.; Cheng, S.B.; Ikawa, M.; Yoshimori, T.; Huber, W.J.; Menon, R. Evidence for lysosomal biogenesis proteome defect and impaired autophagy in preeclampsia. Autophagy 2020, 16, 1771–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, A.; Shima, T.; Yoshida-Kawaguchi, M.; Yamada, K.; Yasuda, I.; Tsuda, S.; Nakashima, A. Chloroquine is a safe autophagy inhibitor for sustaining the expression of antioxidant enzymes in trophoblasts. J Reprod Immunol 2023, 155, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, A.; Shiozaki, A.; Myojo, S.; Ito, M.; Tatematsu, M.; Sakai, M. Granulysin produced by uterine natural killer cells induces apoptosis of extravillous trophoblasts in spontaneous abortion. Am J Pathol 2008, 173, 653–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, A.; Cheng, S.B.; Kusabiraki, T.; Motomura, K.; Aoki, A.; Ushijima, A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress disrupts lysosomal homeostasis and induces blockade of autophagic flux in human trophoblasts. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 11466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.X.; Ma, L.Z.; Liu, S.J.; Zhang, C.T.; Meng, R.; Chen, Y.Z. Protective effects of trehalose on frozen-thawed ovarian granulosa cells of cattle. Anim Reprod Sci 2019, 200, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Cheng, S.; Jash, S.; Fierce, J.; Agudelo, A.; Higashiyama, T. Exploiting sweet relief for preeclampsia by targeting autophagy-lysosomal machinery and proteinopathy. Exp Mol Med 2024, 56, 1206–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamuro, T.; Kawabata, T.; Fukuhara, A.; Saita, S.; Nakamura, S.; Takeshita, H. Age-dependent loss of adipose Rubicon promotes metabolic disorders via excess autophagy. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trujillo, M.; Odle, A.K.; Aykin-Burns, N.; Allen, A.R. Chemotherapy induced oxidative stress in the ovary: drug-dependent mechanisms and potential interventions†. Biol Reprod 2023, 108, 522–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.A.; El, Shourbagy, S. ; St, John, J.C. Mitochondrial content reflects oocyte variability and fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril 2006, 85, 584–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, J.M.; Alesi, L.R.; Winship, A.L.; Hutt, K.J. Beyond apoptosis: evidence of other regulated cell death pathways in the ovary throughout development and life. Hum Reprod Update 2023, 29, 434–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamuro, T.; Nakamura, S.; Yamano, Y.; Endo, T.; Yanagawa, K.; Tokumura, A. Rubicon prevents autophagic degradation of GATA4 to promote Sertoli cell function. PLoS Genet 2021, 17, e1009688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Xu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C. miR-181a increases FoxO1 acetylation and promotes granulosa cell apoptosis via SIRT1 downregulation. Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, e3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, W.D.; Zhang, H.L.; Li, D.D. Acetylation of Beclin 1 inhibits autophagosome maturation and promotes tumour growth. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahm-Daphi, J.; Sass, C.; Alberti, W. Comparison of biological effects of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation and hydrogen peroxide in CHO cells. Int J Radiat Biol 2000, 76, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Liang, G.; Geng, G.; Zhao, F.; Yin, P. CHK2-FOXK axis promotes transcriptional control of autophagy programs. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eaax5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, S.; Hikita, H.; Tatsumi, T.; Sakamori, R.; Nozaki, Y.; Sakane, S. Rubicon inhibits autophagy and accelerates hepatocyte apoptosis and lipid accumulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology 2016, 64, 1994–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Urata, Y.; Harada, M.; Kunitomi, C.; Kusamoto, A.; Koike, H. Cellular senescence of granulosa cells in the pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Hum Reprod 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamuro, T.; Nakamura, S.; Yanagawa, K.; Tokumura, A.; Kawabata, T.; Fukuhara, A. Loss of RUBCN/rubicon in adipocytes mediates the upregulation of autophagy to promote the fasting response. Autophagy 2022, 18, 2686–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Imoto, H.; Minami, S.; Shioda, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Sakai, S.; Maeda, S. Age-associated decline of MondoA drives cellular senescence through impaired autophagy and mitochondrial homeostasis. Cell Rep 2022, 38, 110444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Karalay, Ö.; Jäger, PS.; Horikawa, M.; Klein, C.; Nakamura, K. Mondo complexes regulate TFEB via TOR inhibition to promote longevity in response to gonadal signals. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, M.; Pal, R.; Nelvagal, H.R.; Lotfi, P.; Stinnett, G.R.; Seymour, M.L. mTORC1-independent TFEB activation via Akt inhibition promotes cellular clearance in neurodegenerative storage diseases. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, M.; Cornuau, M.; Cloix, L.; Ramé, C.; Guerif, F.; Royère, D. Visfatin is expressed in human granulosa cells: regulation by metformin through AMPK/SIRT1 pathways and its role in steroidogenesis. Mol Hum Reprod 2013, 19, 313–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).