Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

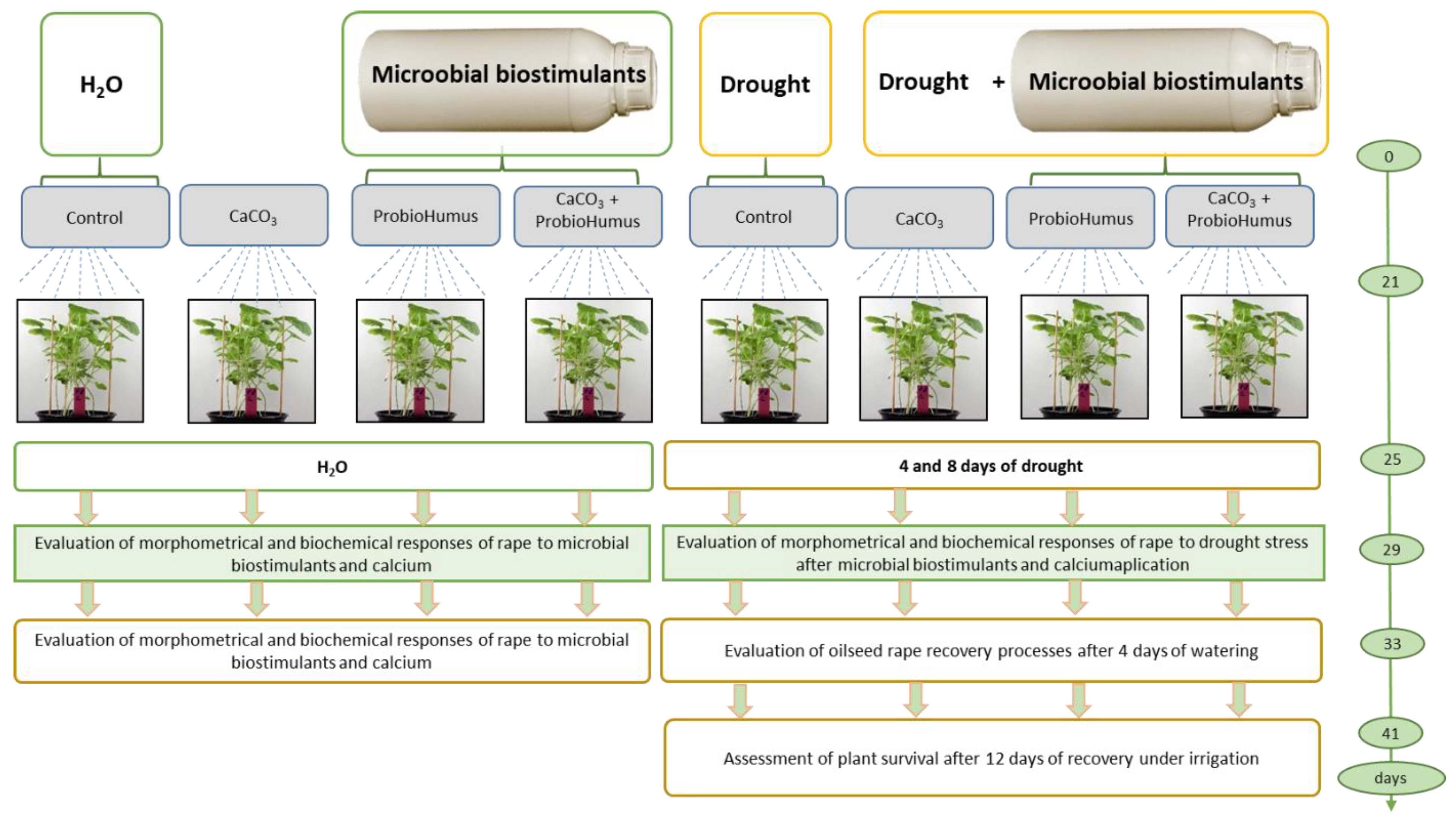

2.1. Plant Growth Conditions and Treatments

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Relative Water Content (RWC) Measurement

2.5. Evaluation of Stomatal Density and Opening

2.6. Estimation of Photosynthetic Pigment Content

2.7. Measurement of MDA Content

2.8. Estimation of Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) Content

2.9. Estimation of Proline Levels

2.10. Estimation of Ethylene Levels

2.11. Estimation of PM ATPase Activity

2.12. Determination of Plant Survival

2.13. One-Way Statistical Analysis by ANOVA

3. Results

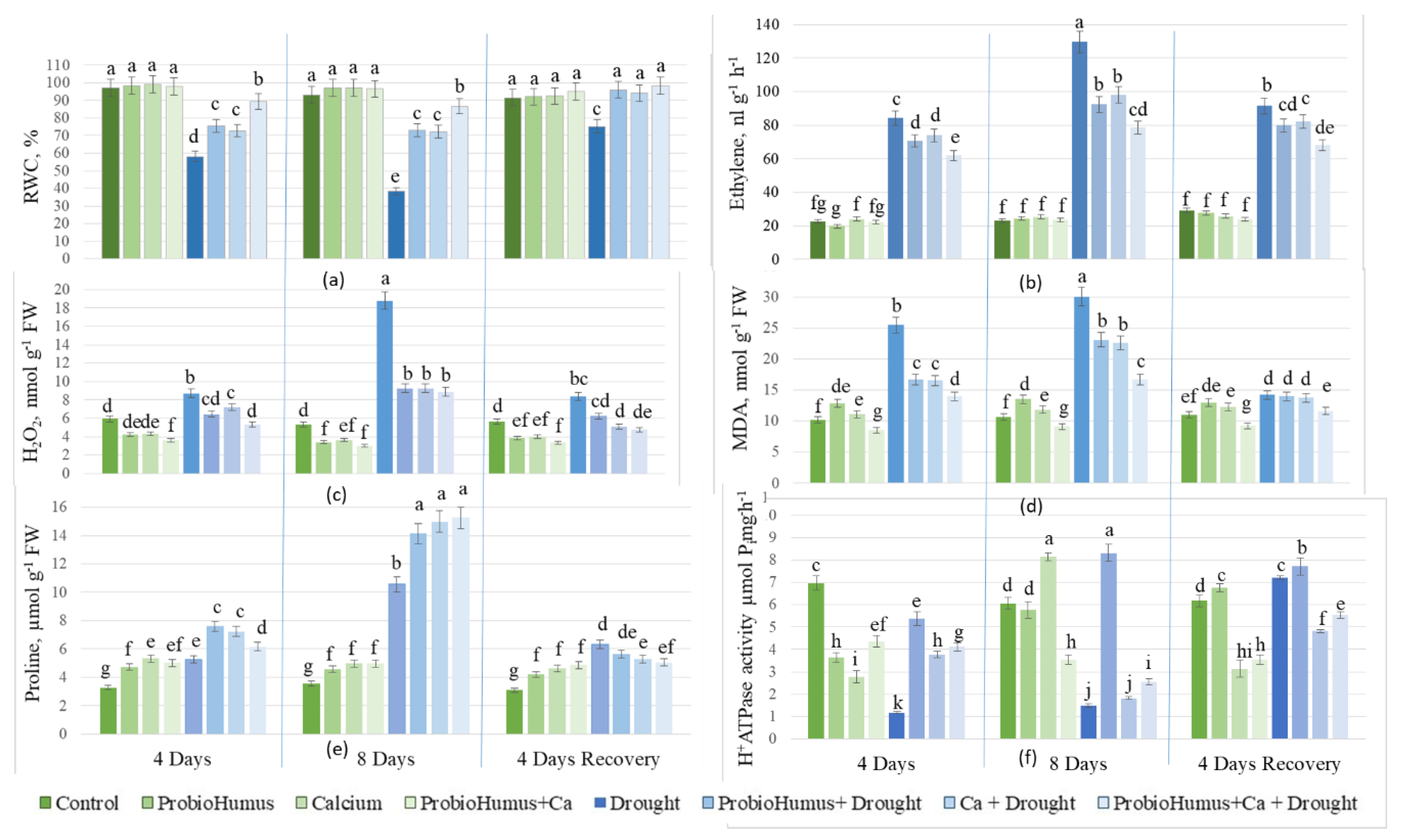

3.1. Effect of Microbial Biostimulant and Ca on Physiological and Biochemical Indicators of Control and Drought Stressed Plants

3.1.1. Leaf RWC

3.1.2. Ethylene Level

3.1.3. H2O2 and MDA Content

3.1.4. Endogenous Proline Content

3.1.5. PM ATPase Activity

3.1.6. Photosynthetic Pigment Content

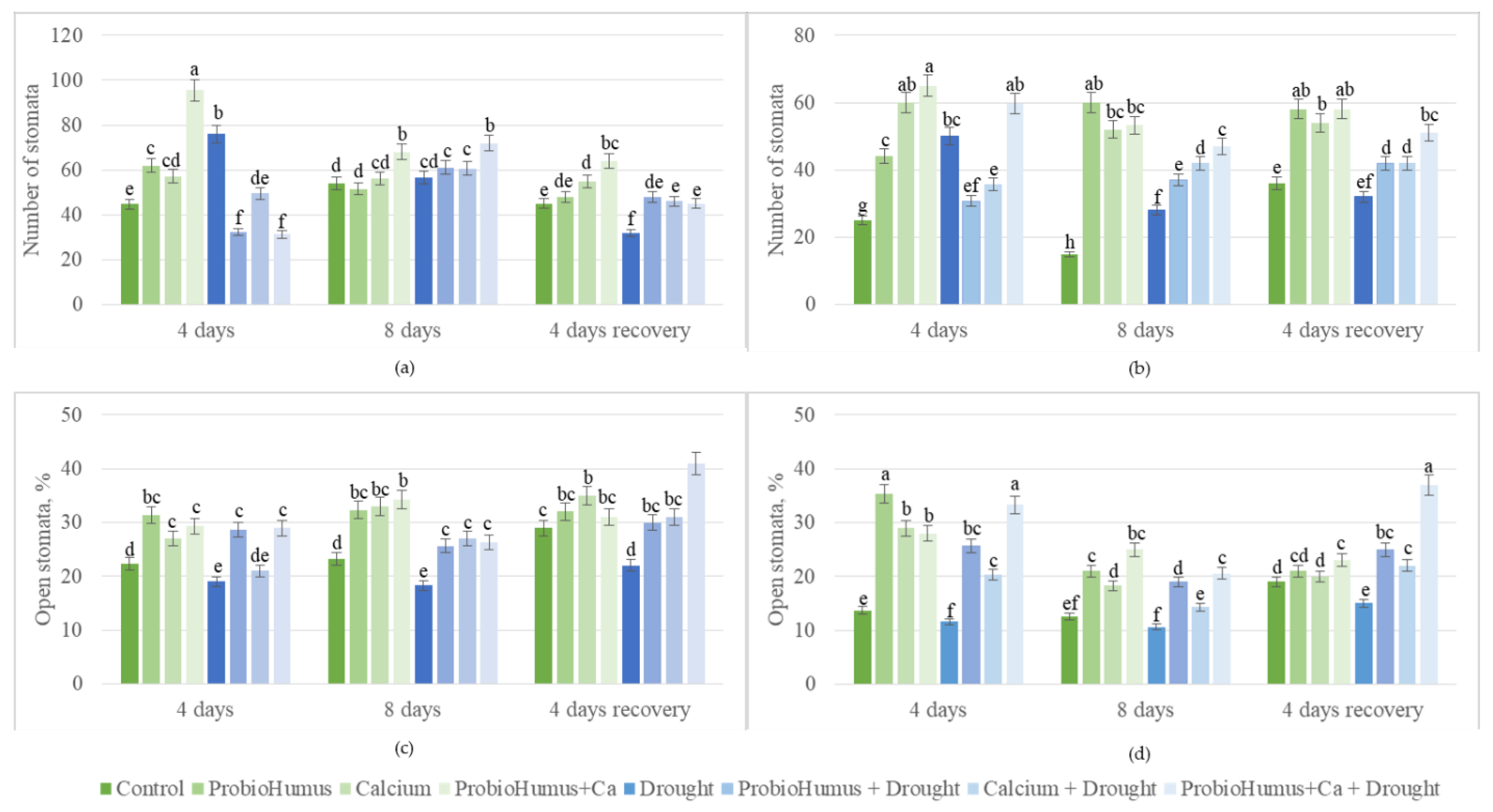

3.2. Effect of Microbial Biostimulant and Ca on Stomata Density and Aperture in Leaves of Control and Drought Stressed Plants

3.3. Effect of Microbial Biostimulant and Ca on Survival of Control and Drought Stressed Plants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Souza Vandenberghe L.P.; Garcia, L.M.B.; Rodrigues, C.; Camara, M.C.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; de Oliveira, J.; Soccol, C.R. Potential applications of plant probiotic microorganisms in agriculture and forestry. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 629–648. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gómez, A.; Celador-Lera, L.; Fradejas-Bayón, M.; Rivas, R. Plant probiotic bacteria enhance the quality of fruit and horticultural crops. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 483–501. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Freitas, H.; Dias, M.C. Strategies and prospects for biostimulants to alleviate abiotic stress in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 10242. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, P.; Seyedsalehi, M.; Paladino, O.; Van Damme, P.; Sillanpää, M.; Sharifi, A. Effect of drought and salinity stresses on morphological and physiological characteristics of canola. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 1859–1866. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Response mechanism of plants to drought stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 50. [CrossRef]

- Batool, M.; El-Badri, A.M.; Hassan, M.U.; Haiyun, Y.; Chunyun, W.; Zhenkun, Y.; Jie, K.; Wang, B; Zhou, G. Drought stress in Brassica napus: effects, tolerance mechanisms, and management strategies. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 21-45. [CrossRef]

- Oladosu, Y.; Rafii, M.Y.; Samuel, C.; Fatai, A.; Magaji, U.; Kareem, I.; Kamarudin, Z.S.; Muhammad, I.; Kolapo, K. Drought resistance in rice from conventional to molecular breeding: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3519. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science. 2020, 368, 266-269. [CrossRef]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. Biostimulants in plant science: a global perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2049. [CrossRef]

- Del Buono, D. Can biostimulants be used to mitigate the effect of anthropogenic climate change on agriculture? It is time to respond. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141763. [CrossRef]

- Higa, T.; Parr, J.F. Beneficial and Effective Microorganisms for a Sustainable Agriculture and Environment, 1st ed.; International Nature Farming Research Center: Atami, Japan, 1994; pp. 1–16.

- Ranty, B.; Aldon, D.; Cotelle, V.; Galaud. J.P.; Thuleau, P.; Mazars, C. Calcium sensors as key hubs in plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 327. [CrossRef]

- Weigand, C.; Kim, S.H.; Brown, E.; Medina, E.; Mares, M.; Miller, G.; Harper, J.F.; Choi, W.G. A ratiometric calcium reporter CGf reveals calcium dynamics both in the single cell and whole plant levels under heat stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 777975. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Memon, A.G.; Ahmad, A.; Iqbal, M.S. Calcium mediated cold acclimation in plants: underlying signaling and molecular mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 855559. [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Zhao, L.; Liu, X. Calcium signaling and the response to heat shock in crop plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 324. [CrossRef]

- Demidchik, V.; Shabala, S.; Isayenkov, S., Cuin, T.A.; Pottosin, I. Calcium transport across plant membranes: mechanisms and functions. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 49-69. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Niu, J.; Jiang, Z. Sensing mechanisms: calcium signaling mediated abiotic stress in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 925863. [CrossRef]

- Ayyaz, A.; Zhou, Y.; Batool, I.; Hannan, F.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Shahzad, K.; Sun, Y.; Farooq, M.A.; Zhou, W. Calcium nanoparticles and abscisic acid improve drought tolerance, mineral nutrients uptake and inhibitor-mediated photosystem II performance in Brassica napus. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 516–537. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Guo, F.; Yang, S.; Zou, J.; Wan, S. Increasing calcium and decreasing nitrogen fertilizers improves peanut growth and productivity by enhancing photosynthetic efficiency and nutrient accumulation in acidic red soil. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1924. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C. Exogenous Ca2+ alleviates waterlogging-caused damages to pepper. Photosynthetica 2016, 54, 620–629. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Wallrad, L.; Almutairi, B.O.; Kudla, J. Ca2+ signaling in plant responses to abiotic stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 287–300. [CrossRef]

- Rezayian, M.; Niknam, V.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Differential responses of phenolic compounds of Brassica napus under drought stress. Iran. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 8, 2417–2425.

- Meier, U. Growth Stages of Mono- and Dicotyledonous Plants. BBCH Monograph, 2nd ed.; Federal Biological Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry: Bonn, Germany, 2001; pp. 115–117.

- Weng, M.; Cui, L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, M.; Shan, L.; Yang, S.; Deng, X.-P. Effects of drought stress on antioxidant enzymes in seedlings of different wheat genotypes. Pak. J. Bot. 2015, 47, 49–56.

- Hilu, K.W.; Randall, J.L. A convenient method for examining the epidermis of grass leaves. Taxon 1984, 33, 413–415.

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.; DeLong, J.; Forney, C.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: Protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59–66.

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [CrossRef]

- Child, R.D.; Chauvaux, N.; John, K.; Van Onckelen, H.A.; Ulvskov, P. Ethylene biosynthesis in oilseed rape pods in relation to pod shatter. J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 829–838. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid method for the quantification of microgram quantities of proteins utilising the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254.

- Darginavičienė, J.; Pašakinskienė, I.; Maksimov, G.; Rognli, O.A.; Jurkonienė, S.; Šveikauskas, V.; Bareikienė, N. Changes in plasmalemma K+ Mg2+-ATPase dephosphorylating activity and H+ transport in relation to freezing tolerance and seasonal growth of Festuca pratensis Huds. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 825–832.

- Raza, A. Eco-physiological and biochemical responses of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) to abiotic stresses: consequences and mitigation strategies. J Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 1368–1388. [CrossRef]

- Kopecká, R.; Kameniarová, M.; Černý, M.; Brzobohatý, B.; Novák, J. Abiotic stress in crop production. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 6603. [CrossRef]

- Van Oosten, M.J.; Pepe, O.; De Pascale, S.; Silletti, S.; Maggio, A. The role of biostimulants and bioeffectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 5. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Asthir, B. Molecular responses to drought stress in plants. Biol. Plant. 2017, 61, 201–209. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Devi, B.M.; Sarkar, A.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Satnami, L.; Balu, P.; Choudhary, M.; Shahid, M.A.; Jailani, A.A.K. Microbial exudates as biostimulants: role in plant growth promotion and stress mitigation. J. Xenobiot. 2023, 13, 572–603. [CrossRef]

- Khushboo, B.K.; Singh, P.; Raina, M.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, D. Exogenous application of calcium chloride in wheat genotypes alleviates negative effect of drought stress by modulating antioxidant machinery and enhanced osmolyte accumulation. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant. 2018, 54, 495–507. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, J.; Ahmed, H.; Kumari, N.; Pandey, A.; Rajneesh, Sinha, R.P. Role of calcium and potassium in amelioration of environmental stress in plants. In Protective Chemical Agents in the Amelioration of Plant Abiotic Stress: Biochemical and Molecular Perspectives, 1st ed.; Roychoudhury, A., Tripathi, D.K., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: New Jersey, USA, 2020, pp. 535–562.

- Vanani, F. R.; Shabani, L.; Sabzalian, M. R.; Dehghanian, F.; Winner, L. Comparative physiological and proteomic analysis indicates lower shock response to drought stress conditions in a self-pollinating perennial ryegrass. Plos One, 2020, 15, e0234317. [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A.; Al Ayoubi, S.; Sher, A.; Bibi, Y.; Ahmad, S.; Shen, Z.; Jenks, M.A. Improvement in drought tolerance in bread wheat is related to an improvement in osmolyte production, antioxidant enzyme activities, and gaseous exchange. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5238–5249. [CrossRef]

- Patanè, C.; Cosentino, S.L.; Romano, D.; Toscano, S. Relative water content, proline, and antioxidant enzymes in leaves of long shelf-life tomatoes under drought stress and rewatering. Plants 2022, 11, 3045. [CrossRef]

- Masheva, V.; Spasova-Apostolva, V.; Aziz, S.; Tomlekova, N. Variations in proline accumulation and relative water content under water stress characterize bean mutant lines (P. vulgaris L.). Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 28, 430–436.

- Naeem, M.; Naeem, M.S.; Ahmad, R.; Ahmad, R. Foliar-applied calcium induces drought stress tolerance in maize by manipulating osmolyte accumulation and antioxidative responses. Pak. J. Bot. 2017, 49, 427–434.

- Yadav, V.K.; Yadav, R.C.; Choudhary, P.; Sharma, S.K.; Bhagat, N. Mitigation of drought stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by inoculation of drought tolerant Bacillus paramycoides DT-85 and Bacillus paranthracis DT-97. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 59–69. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, M.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Peng, C.; Lu, X.; Zhang, M.; Jin, J. Effect of drought on agronomic traits of rice and wheat: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 839. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Hepworth, C.; Dutton, C.; Dunn, J.A.; Hunt, L.; Stephens, J.; Waugh, R.; Cameron, D.D.; Gray, J.E. Reducing stomatal density in Barley improves drought tolerance without impacting on yield. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 776–787. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W-L.; Chen, Y-J.; Brodribb T.J.; Cao, K-F. Weak coordination between vein and stomatal densities in 105 angiosperm tree species along altitudinal gradients in Southwest China. Funct. Plant Biol. 2016, 43, 1126–1133. [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Pei, W. Exploring drought-responsive crucial genes in Sorghum. iScience 2022, 105347.

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Improving water-use efficiency by decreasing stomatal conductance and transpiration rate to maintain higher ear photosynthetic rate in drought-resistant wheat. Crop J. 2017, 5, 231–239.

- Khalil, H.A.; El-Ansary, D.O. Morphological, physiological and anatomical responses of two olive cultivars to deficit irrigation and mycorrhizal inoculation. Eur. J. Hort. Sci. 2020, 85, 5–62. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.E.; Saad, Z.H.; Elsayed, H. The effect of drought on chlorophyll, proline and chemical composition of three varieties of egyptian rice. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 15, 21–30.

- Xie, H.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, W.; Liang, G.; Jia, Z. Important physiological changes due to drought stress on oat. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 644726. [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Babalola, O.O.; Santoyo, G.; Perazzolli, M. The potential role of microbial biostimulants in the amelioration of climate change-associated abiotic stresses on crops. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 829099. [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [CrossRef]

- Lalarukh, I.; Al-Dhumri, S.A.; Al-Ani, L.K.T.; Hussain, R.; Al Mutairi, K.A.; Mansoora, N.; Amjad, S.F.; Abbas, M.H.H.; Abdelhafez, A.A.; Poczai, P.; et al. A Combined use of rhizobacteria and moringa leaf extract mitigates the adverse effects of drought stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 813415. [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Haider, M.Z.; Javed, S.; Saleem, M.H.; Alatawi, A. Drought stress amelioration in maize (Zea mays L.) by inoculation of Bacillus spp. strains under sterile soil conditions. Agriculture 2022, 12, 50.

- Chen, H.; Bullock Jr, D.A.; Alonso, J.M.; Stepanova, A.N. To fight or to grow: The balancing role of ethylene in plant abiotic stress responses. Plants 2021, 11, 33.

- Jasrotia, S.; Jastoria, R. Role of ethylene in combating biotic stress. In Ethylene in Plant Biology, 1st ed.; Singh, S., Husain, T., Singh, V.P., Tripathi, D.K., Prasad, S.M., Dubey, N.K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 388–397.

- Poór, P.; Nawaz, K.; Gupta, R.; Ashfaque, F.; Khan, M.I.R. Ethylene involvement in the regulation of heat stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 675–698. [CrossRef]

- Camaille, M.; Fabre, N.; Clément, C.; Ait Barka, E. Advances in wheat physiology in response to drought and the role of plant growth promoting Rhizobacteria to trigger drought tolerance. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 687. [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Asgher, M.; Iqbal, N.; Rasheed, F.; Sehar, Z.; Sofo, A.; Khan, N.A. Ethylene signaling under stressful environments: analyzing collaborative knowledge. Plants 2022, 11, 2211. [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, L.; Carletti, P.; Badeck, F.W.; Rizza, F.; Morcia, C.; Ghizzoni, R.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Terzi, V.; Lucini, L. Metabolomic responses triggered by arbuscular mycorrhiza enhance tolerance to water stress in wheat cultivars. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 137, 203–212. [CrossRef]

- Pottosin, I.; Olivas-Aguirre, M.; Dobrovinskaya, O.; Zepeda-Jazo, I.; Shabala, S. Modulation of ion transport across plant membranes by polyamines: understanding specific modes of action under stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 616077. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, H.; Xu, F.; Yan, F.; Xu, W. H+-ATPases in plant growth and stress responses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022. 73, 495–521.

- Feng, X.; Liu, W.; Zeng, F.; Chen, Z., Zhang, G.; Wu, F. K+ uptake, H+-ATPase pumping activity and Ca2+ efflux mechanism are involved in drought tolerance of barley. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 129, 57-66. [CrossRef]

- Havshøi, N.W.; Fuglsang, A.T. A critical review on natural compounds interacting with the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase and their potential as biologicals in agriculture. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 268–286. [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujita, D.; Basra, S.M.A. Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management. Sustain. Agric. 2009, 53–188.

- Abdelaal, K.A.A.; Attia, K.A.; Alamery, S.F.; El-Afry, M.M.; Ghazy, A.I.; Tantawy, D.S.; Al-Doss, A.A.; El-Shawy, E.-S.E.; M. Abu-Elsaoud, A.; Hafez, Y.M. Exogenous application of proline and salicylic acid can mitigate the injurious impacts of drought stress on barley plants associated with physiological and histological characters. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1736. [CrossRef]

- Vurukonda, S.S.; Vardharajula S.; Shrivastava, M.; SkZ A. Enhancement of drought stress tolerance in crops by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 184, 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Nayyar, H.; Walia, D.P. Water stress induced proline accumulation in contrasting wheat genotypes as affected by calcium and abscisic acid. Plant Biol. 2003, 46, 275–279. [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, C.A.; Manivannan, B.; Sankar, A.; Kishorekumar M.; Panneerselvam, R. Calcium chloride effects on salinity-induced oxidative stress, proline metabolism and indole alkaloid accumulation in Catharanthus roseus. C. R. Biol. 2007, 330, 674–683.

- Iqbal, M.; Naveed, M.; Sanaullah, M.; Brtnicky, M.; Hussain, M. I.; Kucerik, J.; Mustafa, A. Plant microbe mediated enhancement in growth and yield of canola (Brassica napus L. plant through auxin production and increased nutrient acquisition. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2023, 23, 1233–1249. [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Pigment Contents (mg g−1 FW) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll a | Chlorophyll b | Chlorophyll a/b | Carotenoid | |||||||||

| 4 Days | 8 Days | 4 Days Recovery | 4 Days | 8 Days | 4 Days Recovery | 4 Days | 8 Days | 4 Days Recovery | 4 Days | 8 Days | 4 Days Recovery | |

| Control | 1.42 a | 1.41 a | 1.43 a | 0.37 a | 0.38 a | 0.38 a | 3.84 b | 3.71 d | 3.76 c | 0.36 a | 0.36 a | 0.37a |

| ProbioHumus | 1.46 a | 1.45 a | 1.47 a | 0.39 a | 0.41 a | 0.39 a | 3.74 c | 3.54 e | 3.77 c | 0.38 a | 0.37 a | 0.37 a |

| Calcium | 1.44 a | 1.45 a | 1.46 a | 0.38 a | 0.38 a | 0.37 a | 3.79 c | 3.82 c | 3.95 b | 0.38 a | 0.37 a | 0.37 a |

| ProbioHumus+Ca | 1.43 a | 1.42 a | 1.47 a | 0.39 a | 0.40 a | 0.41 a | 3.67 c | 3.55 e | 3.59 d | 0.39 a | 0.36 a | 0.38 a |

| Drought | 0.99 d | 0.61 c | 0.75 d | 0.25 c | 0.14 c | 0.18 d | 3.96 a | 4.36 a | 4.17 a | 0.31 b | 0.22 c | 0.27 b |

| ProbioHumus+ Drought | 1.24 b | 0.75 b | 0.99 c | 0.32 b | 0.18 b | 0.28 b | 3.88 b | 4.17 b | 3.54 d | 0.36 a | 0.31 b | 0.34 a |

| Ca + Drought | 1.09 c | 0.72 b | 0.83 cd | 0.28 c | 0.17 b | 0.23 c | 3.89 b | 4.24 b | 3.61 d | 0.32 ab | 0.32 b | 0.35 a |

| ProbioHumus+Ca + Drought | 1.23 b | 0.75 b | 1.11 b | 0.32 b | 0.19 b | 0.31 b | 3.84 b | 3.95 c | 3.58 d | 0.37 a | 0.34 ab | 0.35 a |

| Treatment | Number of survived plants (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control, H2O | 100 a | |

| ProbioHumus | 100 a | |

| Ca | 100 a | |

| ProbioHumus + Ca | 100 a | |

| Drought | 34 d | |

| ProbioHumus + Drought | 60 c | |

| Ca + Drought | 69 bc | |

| ProbioHumus + Ca + Drought | 76 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).