Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Selection of Active GABA Concentrations

2.2. Selection of Active Mix GABA + Proline Concentrations

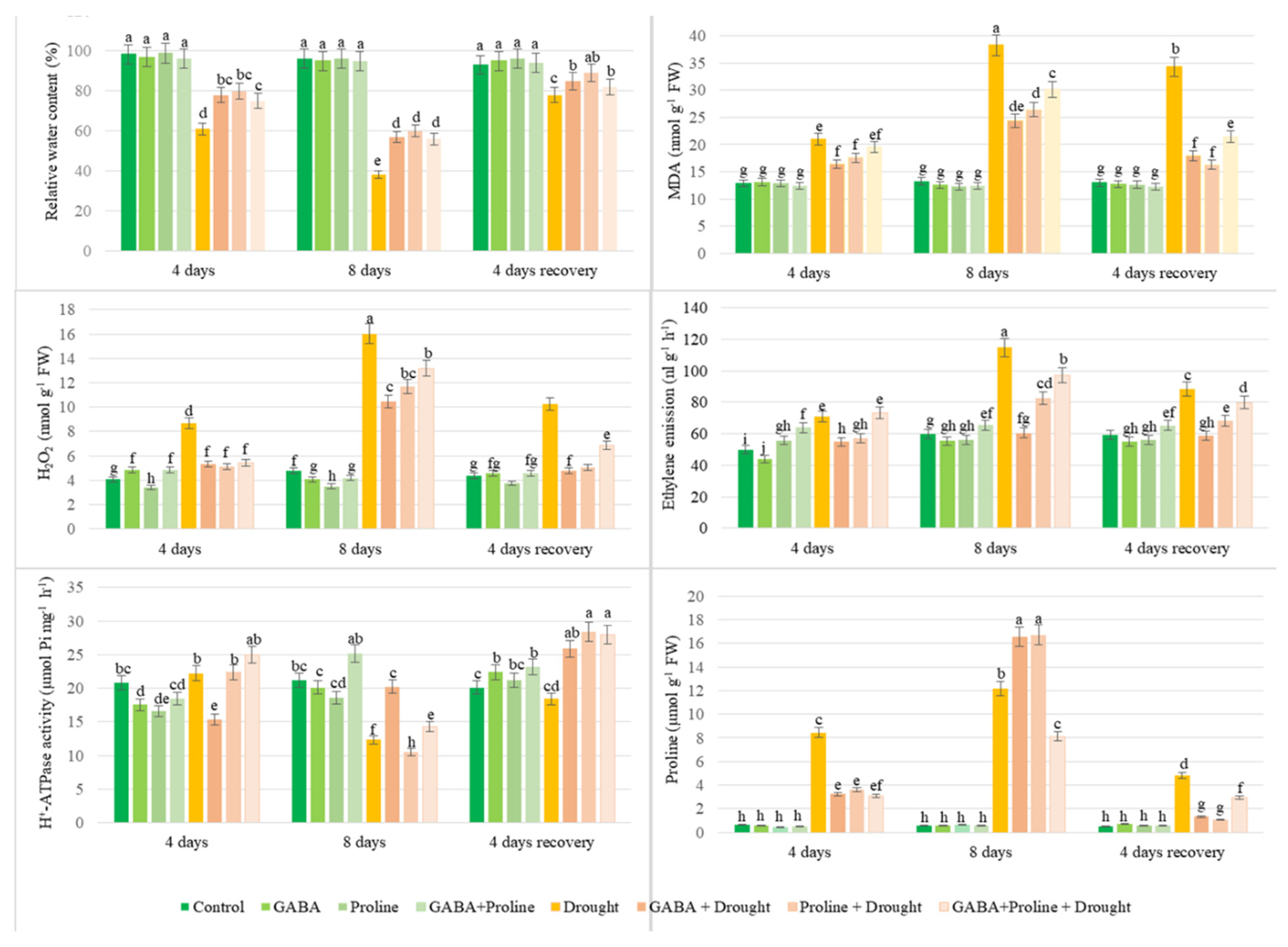

2.3. RWC

2.4. Photosyntetic Pigments

2.5. Ethylene

2.6. Impact of Two Amino Acids on Biochemical Responses of Oilseed Rape Exposed to Prolonged Drought

2.6.1. H2O2

2.6.2. MDA

2.6.3. Free Proline

2.6.4. PM ATPase Activity

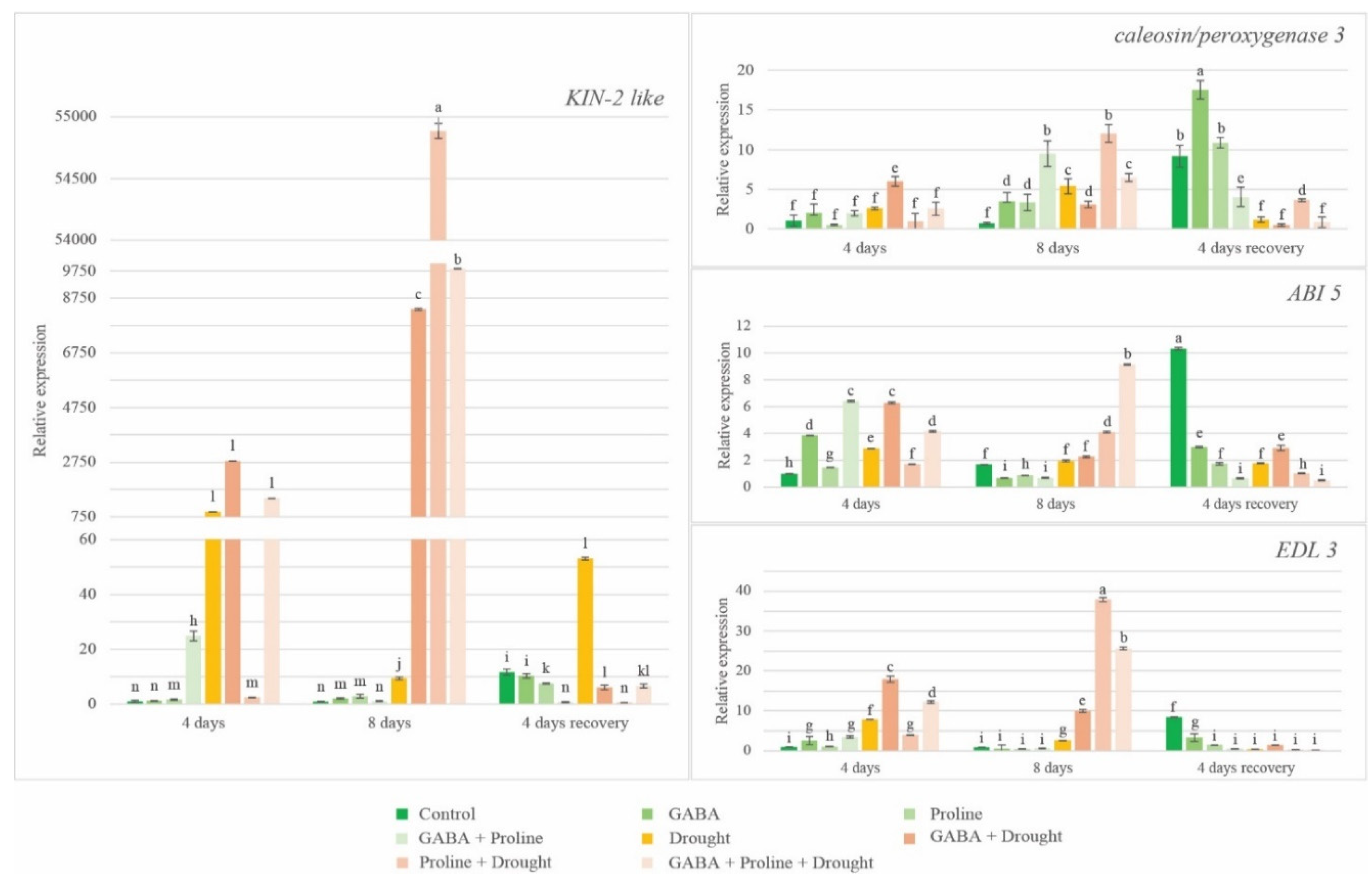

2.6.5. Effect of Amino Acids on Four Genes Expression Levels of Oilseed Rape Exposed to Prolonged Drought

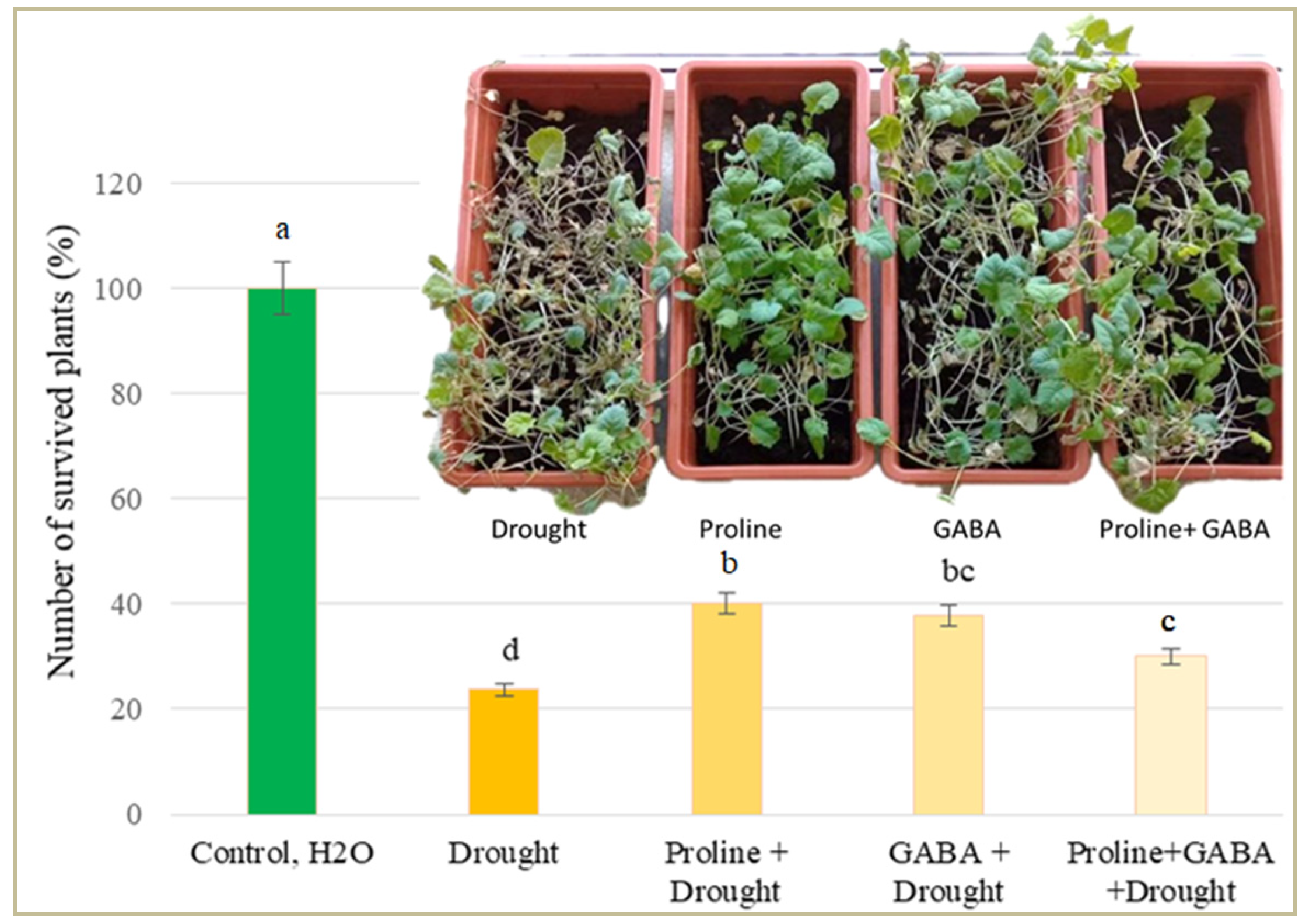

2.6.6. Impact of Exogenous GABA and Proline on Survival of Plants

3. Discussion

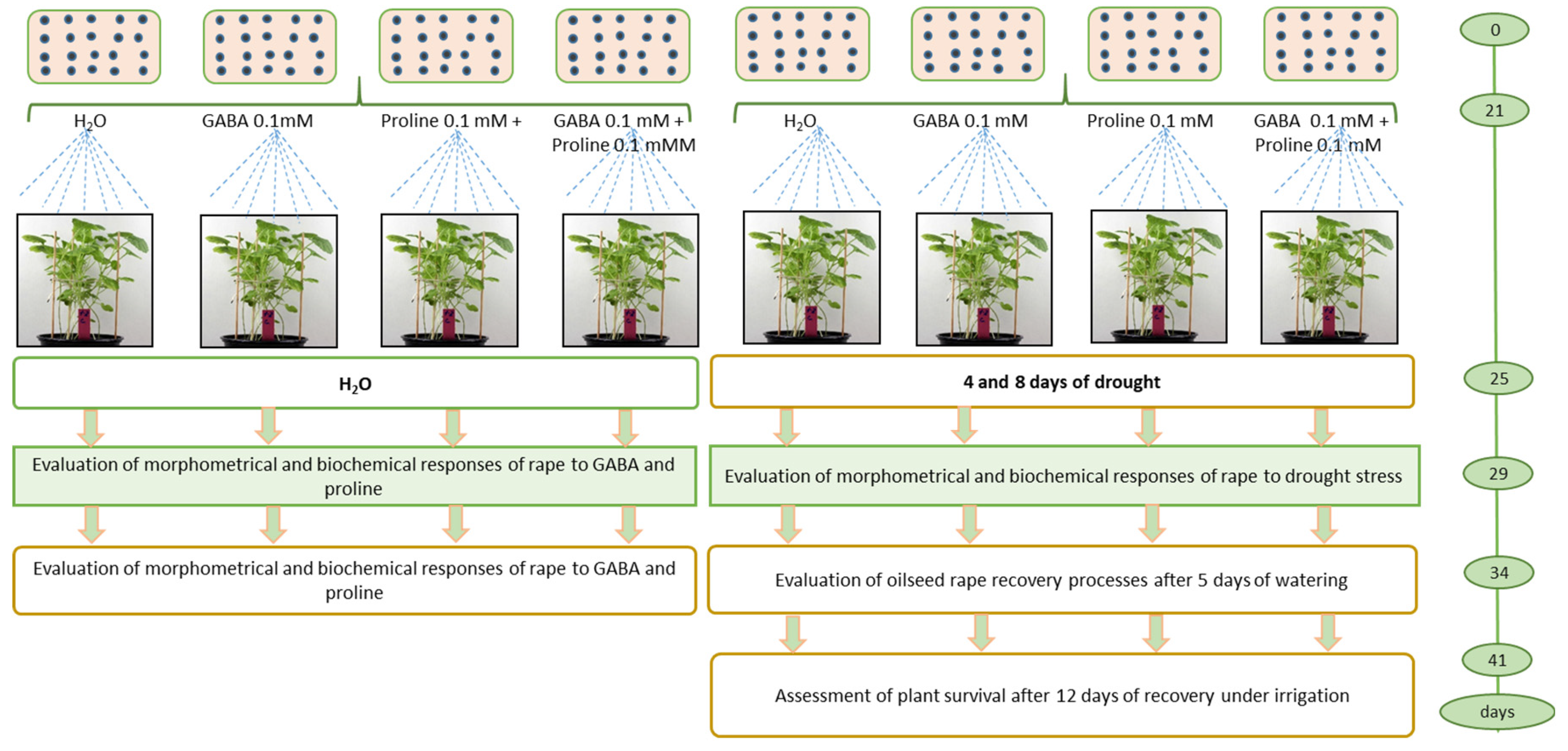

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Object and Growth Conditions

4.2. Treatments

4.2.1. Spraying with Amino Acids

4.2.2. Drought Simulation

4.2.3. Irrigation Renewal

4.3. Determination of the Active GABA Concentration

4.4. Experimental Design

4.5. Sampling

4.7. Determination of Plant Survival

4.8. Assessment of Biochemical Parameters

4.8.1. Photosynthetic Pigments

4.8.2. MDA Content

4.8.3. H2O2 Content

4.8.4. Ethylene Emission

4.8.5. H+-ATPase Activity Assay

4.8.6. Proline

4.9. Molecular Techniques

4.9.1. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

4.9.2. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

4.9.3. Primers

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GABA | γ -aminobutyric acid |

| RWC | Relative water content |

| MDA | malondialdehide |

| FW | fresh weight |

| DW | dried weight |

| SW | saturated weight |

| TCA | Trichloroacetic acid |

References

- Tesfamariam, E.H.; Annandale, J.G.; Steyn, J.M. Water stress effects on winter canola growth and yield. Agron. J. 2010, 102, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionita, M.; Nagavciuc, V.; Kumar, R.; Rakovec, O. On the curious case of the recent decade, mid-spring precipitation deficit in Central Europe. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 3, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, U.M.; Aamer, M.; Umer Chattha, M.; Haiying, T.; Shahzad, B.; Barbanti, L. ; Critical role of zinc in plants facing the drought stress. Agriculture 2020, 10, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, L.; Jin-Qiang, W.; Qing, L. Photosynthesis product allocation and yield in sweet potato with spraying exogenous hormones under drought stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 253, 153265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doneva, D.; Pál, M.; Brankova, L.; Szalai, G.; Tajti, J.; Khalil, R.; Peeva, V. The effects of putrescine pre-treatment on osmotic stress responses in drought-tolerant and drought-sensitive wheat seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 171, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, R.; Nawaz, M.S.; Siddique, M.J.; Hakim, S.; Imran, A. Plant survival under drought stress: Implications, adaptive responses, and integrated rhizosphere management strategy for stress mitigation. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 242, 126626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semida, W.M.; Abdelkhalik, A.; Rady, M.O.A.; Marey, R.A.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A. Exogenously applied proline enhances growth and productivity of drought stressed onion by improving photosynthetic efficiency, water use efficiency and up-regulating osmoprotectants. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.; Funck, D.; Forlani, G.; Okumoto, S.; Amir, R. Amino acids in plants: Regulation and functions in development and stress defense. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 772810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinifard, M.; Stefaniak, S.; Ghorbani Javid, M.; Soltani, E.; Wojtyla, Ł.; Garnczarska, M. Contribution of exogenous proline to abiotic stress tolerance in plants: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Nawaz, A.; Chaudhry, M.; Indrasti, R.; Rehman, A. Improving resistance against terminal drought in bread wheat by exogenous application of proline and gamma-aminobutyric acid. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2017, 203, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelp, B.J.; Aghdam, M.S.; Flaherty, E.J. γ-Aminobutyrate (GABA) Regulated Plant Defense: Mechanisms and Opportunities. Plants 2021, 10, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.M.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Alharbi, B.M.; Waseem, M.; Yao, G.; Liu, X.D. GABA: a key player in drought stress resistance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yu, J.; Peng, Y.; Huang, B. Metabolic pathways regulated by abscisic acid, salicylic acid and γ-aminobutyric acid in association with improved drought tolerance in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). Physiol. Plant. 2017, 159, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, B.; Xie, H.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.P.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, G.; Peng, Y. Exogenous application of GABA improves PEG-induced drought tolerance positively associated with GABA-shunt, polyamines, and proline metabolism in white clover. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razik, A.E.S.; Alharbi, B.M.; Pirzadah, T.B.; Alnusairi, G.S.H.; Soliman, M.H.; Hakeem, K.R. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) mitigates drought and heat stress in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) by regulating its physiological, biochemical, and molecular pathways. Physiol. Plant. 2020, 172, 505–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffagni, V.; Vurro, F.; Janni, M.; Gullì, M.; Keller, A.A.; Marmiroli, N. Shaping durum wheat for the future: Gene expression analyses and metabolites profiling support the contribution of BCAT genes to drought stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quraan, N.A.; Samarah, N.H.; Tanash, A.A. Effect of drought stress on wheat (Triticum durum) growth and metabolism: Insight from GABA shunt, reactive oxygen species, and dehydrin genes expression. Funct. Plant Biol. 2024, 51, 22177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mason, A.S.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Luo, T.; Redden, R.; Batley, J.; Hu, L.; Yan, G. Identification of putative candidate genes for water stress tolerance in canola (Brassica napus). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundertmark, M.; Hincha, D.K. LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) proteins and their encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkela, S.; Borg-Franck, M. Structure and expression of kin2, one of two cold- and ABA-induced genes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992, 19, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, M.; Murphy, D.J. Roles of a membrane-bound caleosin and putative peroxygenase in biotic and abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koops, P.; Pelser, S.; Ignatz, M.; Klose, C.; Marrocco-Selden, K.; Kretsch, T. EDL3 is an F-box protein involved in the regulation of abscisic acid signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 5547–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skubacz, A.; Daszkowska-Golec, A.; Szarejko, I. The role and regulation of ABI5 (ABA-Insensitive 5) in plant development, abiotic stress responses and phytohormone. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanani, F.R. Comparative physiological and proteomic analysis indicates lower shock response to drought stress conditions in a self-pollinating perennial ryegrass. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamanga, R.M.; Mbega, E.; Ndakidemi, P. Drought tolerance mechanisms in plants: physiological responses associated with water deficit stress in Solanum lycopersicum. ACST 2018, 6, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A.; Al Ayoubi, S.; Sher, A.; Bibi, Y.; Ahmad, S.; Shen, Z.; Jenk,s M. A. Improvement in drought tolerance in bread wheat is related to an improvement in osmolyte production, antioxidant enzyme activities, and gaseous exchange. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5238–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.A.R.F.; Hui, L.; Yang, L.J.; Xian, Z.H. Assessment of drought tolerance of some Triticum L. species through physiological indices. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2012, 48, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.; Cui, L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, M.; Shan, L.; Yang, S.; Deng, X.P. Effects of drought stress on antioxidant enzymes in seedlings of different wheat genotypes. Pak. J. Bot. 2015, 47, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, B.; Hussain, F.; Khan, M.S.; Iqbal, T.; Shah, W.; Ali, B.; Al Syaad, K.M.; Ercisli, S. Physiology of gamma-aminobutyric acid treated Capsicum annuum L. (Sweet pepper) under induced drought stress. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, N.A.; Iqbal, M.; Muhammad, A.; Ashraf, M.; Al-Qurainy, F.; Shafiq, S. Aminolevulinic acid and nitric oxide regulate oxidative defense and secondary metabolisms in canola (Brassica napus L.) under drought stress. Protoplasma 2018, 255, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Anee, T.I.; Khan, M.I.R.; Fujita, M. Silicon-mediated regulation of antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems confers drought stress tolerance in Brassica napus L. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 115, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, P.; Seyedsalehi, M.; Paladino, O.; Van Damme, P.; Sillanpää, M.; Sharifi, A.A. Effect of drought and salinity stresses on morphological and physiological characteristics of canola. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyaz, A.; Farooq, M.A.; Dawood, M.; Majid, A.; Javed, M.; Athar, H.U.R.; Zafar, Z.U. Exogenous melatonin regulates chromium stress-induced feedback inhibition of photosynthesis and antioxidative protection in Brassica napus cultivars. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 2063–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; He, C.G.; Wang, Y.J.; Bi, Y.F.; Jiang, H. Effect of drought and heat stresses on photosynthesis, pigments, and xanthophyll cycle in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Photosynthetica 2020, 58, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaljević, I.; Vuletić, V.M.; Šimić, D.; Tomaš, V.; Horvat, D.; Josipović, M.; Zdunić, Z.; Dugalić, K.; Vuković, D. Comparative study of drought stress effects on traditional and modern apple cultivars. Plants 2021, 10, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Selwey, W.A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Shady, M.; Alsadon, A.A. Foliar applications of ZnO and SiO2 nanoparticles mitigate water deficit and enhance potato yield and quality traits. Agronomy 2023, 13, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, K.A.; Attia, K.A.; Alamery, S.F.; El-Afry, M.M.; Ghazy, A.I.; Tantawy, D.S.; Al-Doss, A.A.; El-Shawy, E.E.; Abu-Elsaoud, A.M.; Hafez, Y.M. Exogenous application of proline and salicylic acid can mitigate the injurious impacts of drought stress on barley plants associated with physiological and histological characters. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, S.; Saleem, M.F.; Sarwar, M.; Irshad, M.; Shakoor, A. ; Biochemically triggered heat and drought stress tolerance in rice by proline application. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, H.; Tahir, M.H.N.; Sadaqat, H.A.; Sadia, B. Screening of sunflower (Helianthus annus L.) accessions under drought stress conditions, an experimental assay. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2017, 17, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.K.; Munir, S.; Shahzad, A.N.; Rasul, S.; Nouman, W.; Aslam, K. Role of reactive oxygen species and contribution of new players in defense mechanism under drought stress in rice. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2018, 20, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Barzotto, G.R.; Cardoso, C.P.; Jorge, L.G.; Campos, F.G.; Boaro, C.S.F. Hydrogen peroxide signal photosynthetic acclimation of Solanum lycopersicum L. cv Micro-Tom under water deficit. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, D.; Sergiev, I.; Katerova, Z.; Shopova, E.; Dimitrova, L.; Brankova, L. Assessment of the biochemical responses of wheat seedlings to soil drought after application of selective herbicide. Plants 2021, 10, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, I.; De, A.K.; Sarkar, B.; Ghosh, A.; Dey, N.; Adak, M.K. Cellular response of oxidative stress when sub1A QTL of rice receives water deficit stress. Plant Sci. Today 2018, 5, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumari, K.; Puthur, J.T. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) priming enhances the osmotic stress tolerance in Piper nigrum Linn. plants subjected to PEG-induced stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 78, 57–67.

- Pottosin, I.; Olivas-Aguirre, M.; Dobrovinskaya, O.; Zepeda-Jazo, I.; Shabala, S. Modulation of ion transport across plant membranes by polyamines: understanding specific modes of action under stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 616077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Y. The molecular mechanism of plasma membrane H+-ATPases in plant responses to abiotic stress. J. Genet. Genomics 2022, 49, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, C.; Ziwen, Z.; Yeyun, L.; Xianchen, Z. Exogenously applied Spd and Spm enhance drought tolerance in tea plants by increasing fatty acid desaturation and plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 170, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Liu, W.; Zeng, F.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, G.; Wu, F. K+ uptake, H+-ATPase pumping activity and Ca2+ efflux mechanism are involved in drought tolerance of barley. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 129, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.; Ziwen, Z.; Yeyun, L.; Xianchen, Z. Exogenously applied Spd and Spm enhance drought tolerance in tea plants by increasing fatty acid desaturation and plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 170, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Zivcak, M.; Brestic, M.; Sytar, O. Osmotic adjustment and plant adaptation to drought stress. In Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants. Physiol. Biochem.; 2016; 1, 105–143. 1.

- Khanna-Chopra, R.; Semwal, V.K.; Lakra, N.; Pareek, A. Proline–A key regulator conferring plant tolerance to salinity and drought. In Plant Tolerance to Environmental Stress; CRC Press: 2019; 59–80.

- Ozturk, M.; Turkyilmaz Unal, B.; García-Caparrós, P.; Khursheed, A.; Gul, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Osmoregulation and its actions during the drought stress in plants. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1321–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekka, S.; Abrous-Belbachir, O.; Djebbabar, R. Effects of exogenous proline on the physiological characteristics of Triticum aestivum L. and Lens culinaris Medik. under drought stress. Acta Agric. Slovenica 2018, 111, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semida, W.M.; Abdelkhalik, A.; Rady, M.O.A.; Marey, R.A.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A. Exogenously applied proline enhances growth and productivity of drought stressed onion by improving photosynthetic efficiency, water use efficiency and up-regulating osmoprotectants. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Peng, Y.; Huang, B. Physiological effects of γ-aminobutyric acid application on improving heat and drought tolerance in creeping bentgrass. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 141, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Iqbal, N.; Masood, A.; Per, T.S.; Khan, N.A. Salicyclic acid alleviates adverse effects of heat stress on photosynthesis through changes in proline production and ethylene formation. Plant Signal Behav. 2013, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Manghwar, H.; Shaban, M.; Khan, A.H.; Akbar, A.; Ali, U.; Fahad, S. Phytohormones enhanced drought tolerance in plants: a coping strategy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 33103–33118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Van den Broeck, L.; Inzé, D. The pivotal role of ethylene in plant growth. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Kumar, R.; Kohli, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Kapoor, D.; Bali, A.S. ; Shahzad, B; Khanna, K, Kumar, S, Thukral, A.K., Eds.; Bhardwaj, R. Abiotic stress management in plants: role of ethylene. Molecular Plant Abiotic Stress: Biology and Biotechnology, 2019, 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, F.; Maeta, E.; Terashima, A.; Shigeo, T. Positive role of a wheat HvABI5 ortholog in abiotic stress response of seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 134, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: a multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Caplan, A. Products of proline catabolism can induce osmotically regulated genes in rice. Plant Physiol. 1998, 116, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, U. Growth stages of mono and dicotyledonous plants. In BBCH Monograph; Meier, U., Ed.; Julius Kühn-Institut: Quedlinburg, Germany, 2018; pp. 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, R.A.; Borella, J.; Hüther, C.M.; Drought-induced stress in leaves of Coix lacryma-jobi L. under exogenous application of proline and GABA amino acids. Braz. J. Bot. 2020, 43, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Hassan, M.J.; Kang, D.; Peng, Y.; Li, Z. Photosynthetic maintenance and heat shock protein accumulation relating to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-regulated heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 141, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkonienė, S.; Mockevičiūtė, R.; Gavelienė, V.; Šveikauskas, V.; Zareyan, M.; Jankovska-Bortkevič, E.; Jankauskienė, J.; Žalnierius, T.; Kozeko, L. Proline enhances resistance and recovery of oilseed rape after a simulated prolonged drought. Plants 2023, 12, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, D.; DeLong, J.; Forney, C.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.S. Principles and Techniques of Plant Physiological Biochemical Experiment, 1st ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 94–196. [Google Scholar]

- Alexieva, V.; Sergiev, I.; Mapelli, S.; Karanov, E. The effect of drought and ultraviolet radiation on growth and stress marker in pea and wheat. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, R.D.; Chauvaux, N.; John, K.; Van Onckelen, H.A.; Ulvskov, P. Ethylene biosynthesis in oilseed rape pods in relation to pod shatter. J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darginavičienė, J.; Pašakinskienė, I.; Maksimov, G.; Rognli, O.A.; Jurkonienė, S.; Šveikauskas, V.; Bareikienė, N. Changes in plasmalemma K+, Mg2+-ATPase dephosphorylating activity and H+ transport in relation to freezing tolerance and seasonal growth of Festuca pratensis Huds. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo, P.; Gibon, Y. Extraction and determination of proline. Available online: http://prometheuswiki.publish.csiro.au/tikiindex.php?page=Extraction$+$and$+$determination$+$of$+$proline (accessed on 10 July 2016).

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.P.; Qin, L.; Li, Y.S.; Liao, X.S.; Xu, Z.X.; Hu, X.J.; Xie, L.H.; Yu, C.B.; Wu, Y.F.; Liao, X. Identification of suitable reference genes in leaves and roots of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) under different nutrient deficiencies. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment (3 ml) | RWC, % | Average Fresh Weight per Plant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 days | 8 days | g | % | |||

| Control, H2O | 76.8 ± 0.1 | 79.1 ± 5.3 | 0.97 ± 0.31 | 100 | ||

| GABA 0.1 mM | 78.1 ± 2.6 | 77.6 ± 2.1 | 0.97 ± 0.30 | 100 | ||

| GABA 1 mM | 76.9 ± 5.0 | 80.7 ± 2.5 | 0.83 ± 0.38 | 86 | ||

| GABA 10 mM | 74.4 ± 2.8 | 73.0 ± 0.8 | 0.95 ± 0.50 | 98 | ||

| Drought | 62.9 ± 2.4 | 42.8 ± 1.0 | 0.68 ± 0.27 | 100 | ||

| GABA 0.1 mM + Drought | 71.1 ± 0.9 | 58.4 ± 1.5 | 0.82 ± 0.18 | 121 | ||

| GABA 1 mM + Drought | 67.2 ± 3.0 | 56.1 ± 8.2 | 0.79 ± 0.17 | 116 | ||

| GABA 10 mM + Drought | 65.9 ± 1.6 | 54.3 ± 7.0 | 0.83 ± 0.17 | 122 | ||

| Treatment (12.5 ml) | ||||||

| Control, H2O | 76.2 ± 3.2 | 77.0 ± 1.3 | 1.13 ± 0.34 | 100 | ||

| GABA 0.1 mM | 76.6 ± 4.0 | 80.2 ± 2.0 | 1.18 ± 0.28 | 104 | ||

| GABA 1 mM | 75.4 ± 4.0 | 79.8 ± 2.0 | 1.18 ± 0.32 | 104 | ||

| GABA 10 mM | 75.4 ± 1.6 | 80.1 ± 3.5 | 1.16 ± 0.44 | 103 | ||

| Drought | 60.4 ± 6.9 | 38.0 ± 6.2 | 0.78 ± 0.52 | 100 | ||

| GABA 0.1 mM + Drought | 63.5 ± 5.1 | 60.0 ± 5.1 | 0.99 ± 0.41 | 127 | ||

| GABA 1 mM + Drought | 59.3 ± 2.1 | 56.5 ± 2.1 | 0.91 ± 0.41 | 117 | ||

| GABA 10 mM + Drought | 63.1 ± 2.5 | 54.0 ± 2.5 | 0.93 ± 0.42 | 119 | ||

| Treatment (12.5 ml) | Number of survived plants (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control, H2O | 100 a | |

| GABA 0.1 mM | 100 a | |

| GABA 1 mM | 100 a | |

| GABA 10 mM | 100 a | |

| Drought | 25 d | |

| GABA 0.1 mM + Drought | 83 bc | |

| GABA 1 mM + Drought | 75 c | |

| GABA 10 mM + Drought | 67 c |

| Treatment (12.5 ml) | Average Fresh Weight per Plant | Number of survived plants (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| g | % | ||

| Control, H2O | 1.64 ± 0.57 | 100 | 100 |

| Proline 1 mM + GABA 0.1 mM | 1.68 ± 0.66 | 102 | 100 |

| Proline 0.1 mM + GABA 0.1 mM | 1.90 ± 0.69 | 116 | 100 |

| Drought | 0.69 ± 0.31 | 100 | 27 |

| Proline 1 mM + GABA 0.1 mM + Drought | 0.93 ± 0.29 | 135 | 64 |

| Proline 0.1 mM + GABA 0.1 mM +Drought | 1.43 ± 0.50 | 121 | 85 |

| Treatment | Pigment Contents (mg g−1 FW) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll a | Chlorophyll b | Carotenoids | |||||||

| 4 Days | 8 Days | 4 Days Recovery | 4 Days | 8 Days | 4 Days Recovery | 4 Days | 8 Days | 4 Days Recovery | |

| Control, H2O | 1.24a | 1.27a | 1.28a | 0.38a | 0.33a | 0.34a | 0.34 a | 0.34 b | 0.34 a |

| GABA | 1.27a | 1.25a | 1.23a | 0.37a | 0.34a | 0.32a | 0.36 a | 0.37 a | 0.35 a |

| Proline | 1.28a | 1.26a | 1.22a | 0.37a | 0.32a | 0.35a | 0.35 a | 0.37 a | 0.34 a |

| GABA+Proline | 1.28a | 1.24a | 1.29a | 0.34a | 0.32a | 0.32a | 0.36 a | 0.36 a | 0.35 a |

| Drought | 0.92c | 0.54c | 0.75d | 0.20c | 0.11c | 0.16c | 0.29 b | 0.23 c | 0.25 b |

| GABA+Drought | 1.16b | 0.72b | 1.09b | 0.27b | 0.17b | 0.27b | 0.35 a | 0.31 b | 0.34 a |

| Proline+Drought | 1.18b | 0.70b | 1.04b | 0.29b | 0.16b | 0.26b | 0.38 a | 0.32 b | 0.35 a |

| GABA+Proline+Drought | 1.14b | 0.75b | 0.99bc | 0.27b | 0.17b | 0.24b | 0.32 a | 0.33 b | 0.34 a |

| Gene locus in Brassica napus | Gene name | Forward primer sequence (5′ → 3′) | Reverse primer sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BnaA03g27910D | KIN 2-like | GCCAGACTAAGGAGAAGACAAGT | TGTTCTTGTTCATGCCGGTTT |

| BnaA05g10200D | caleosin/peroxygenase 3 | TGCCATCACCATTACTGCCT | CGGTTCCCCTCGGTTAAGTT |

| BnaC04g09800D | EDL 3 (EID 1 like F-box protein 3), | GTGGGTGGTGGCGGAGAA | CCGCCTGTCTCCTCACGA |

| BnaA05g08020D | ABI 5 | TAAGCAGCCGAGTCTTCCAC | ACCACCGCCGTTATTAGCAT |

| BnaA02g00190D | ACT7 | CCTCTCAACCCGAAAGCCAA | CATCACCAGAGTCGAGCACA |

| BnaA06g27860D | UBC21 | TATCCTCTGCAGCCTCCTCA | CTGTCTGCCTCAGGATGAGC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).