Submitted:

31 January 2023

Posted:

31 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and Conditions for Planting

2.2. Experimental Design and Irrigation Treatments

2.3. Morphological Characteristics

2.4. Physiological and Biochemical Characteristics

2.5. Photosynthetic Pigments Analysis

2.6. RWC in Leaves

2.7. POD Activity Determination

2.8. Proline Content

2.9. DTI

2.10. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

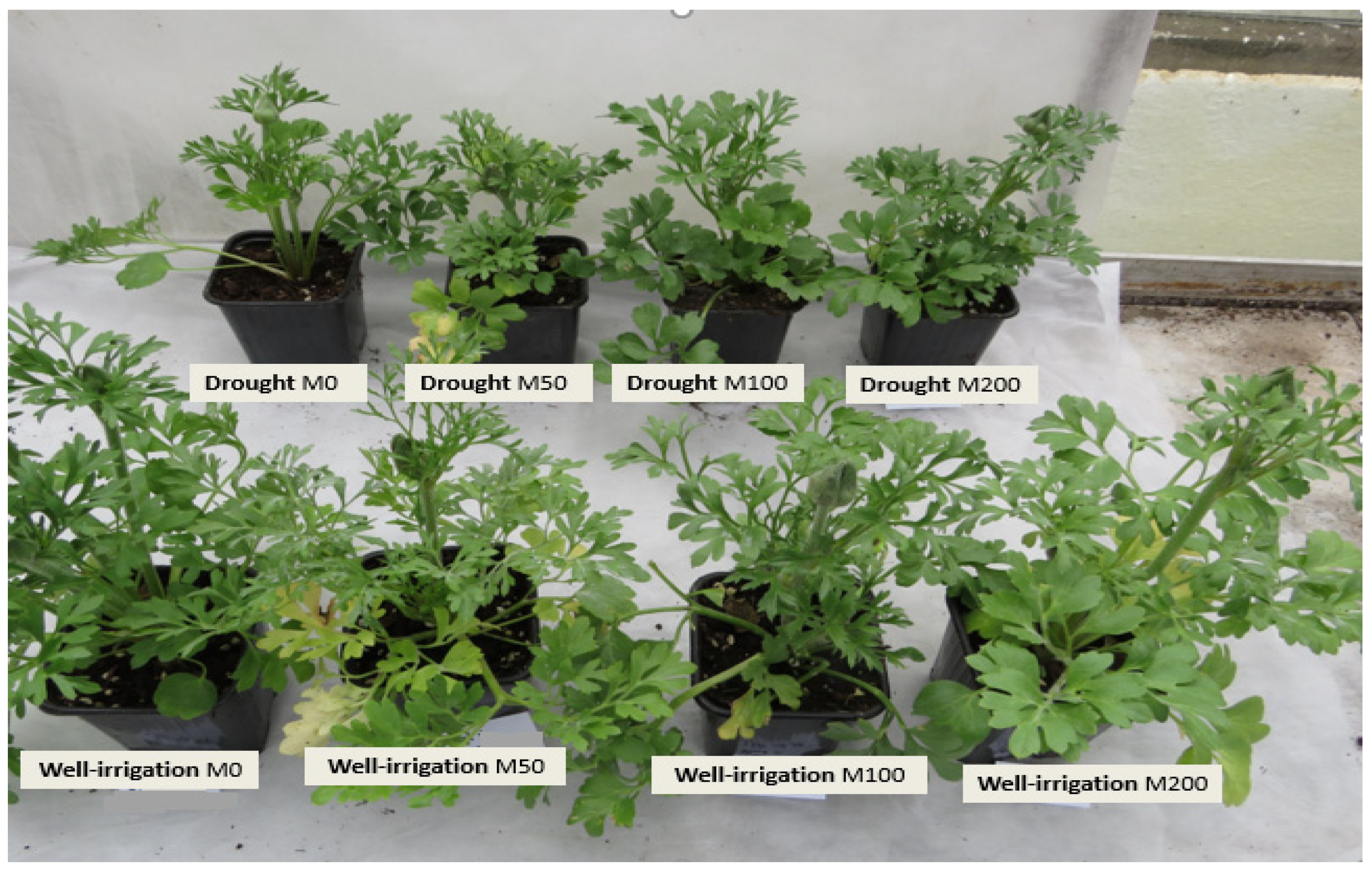

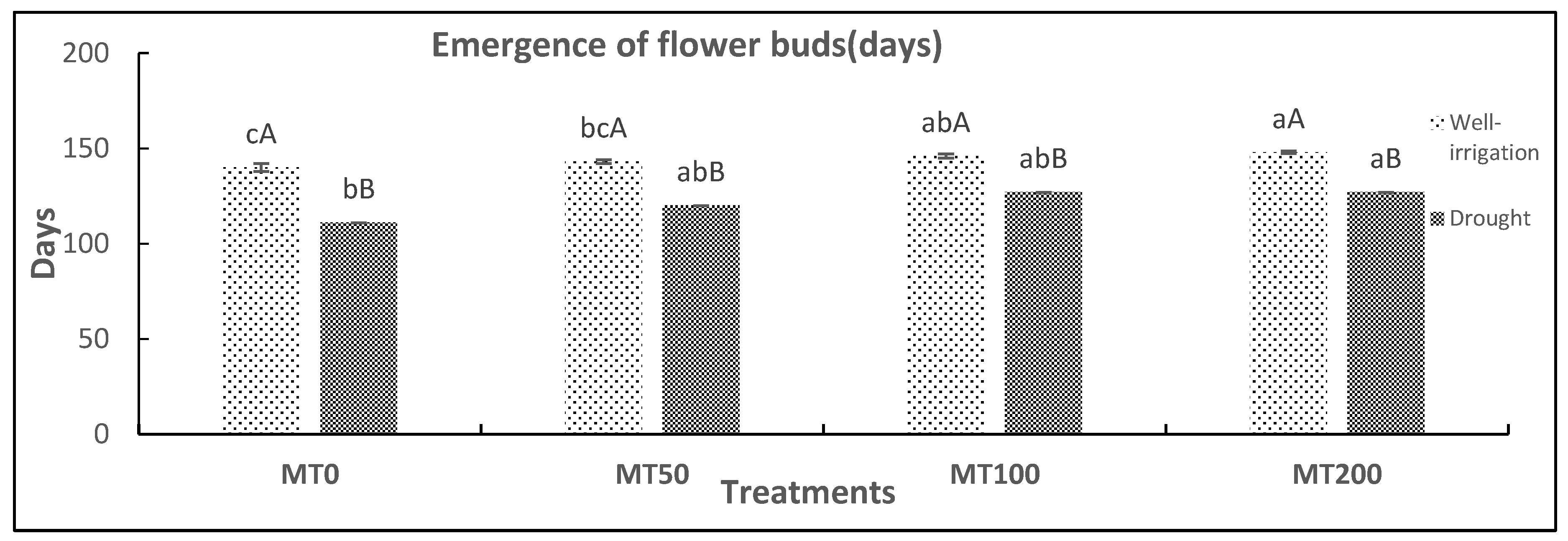

3.1. Impact of MT on Morphology under Drought Conditions

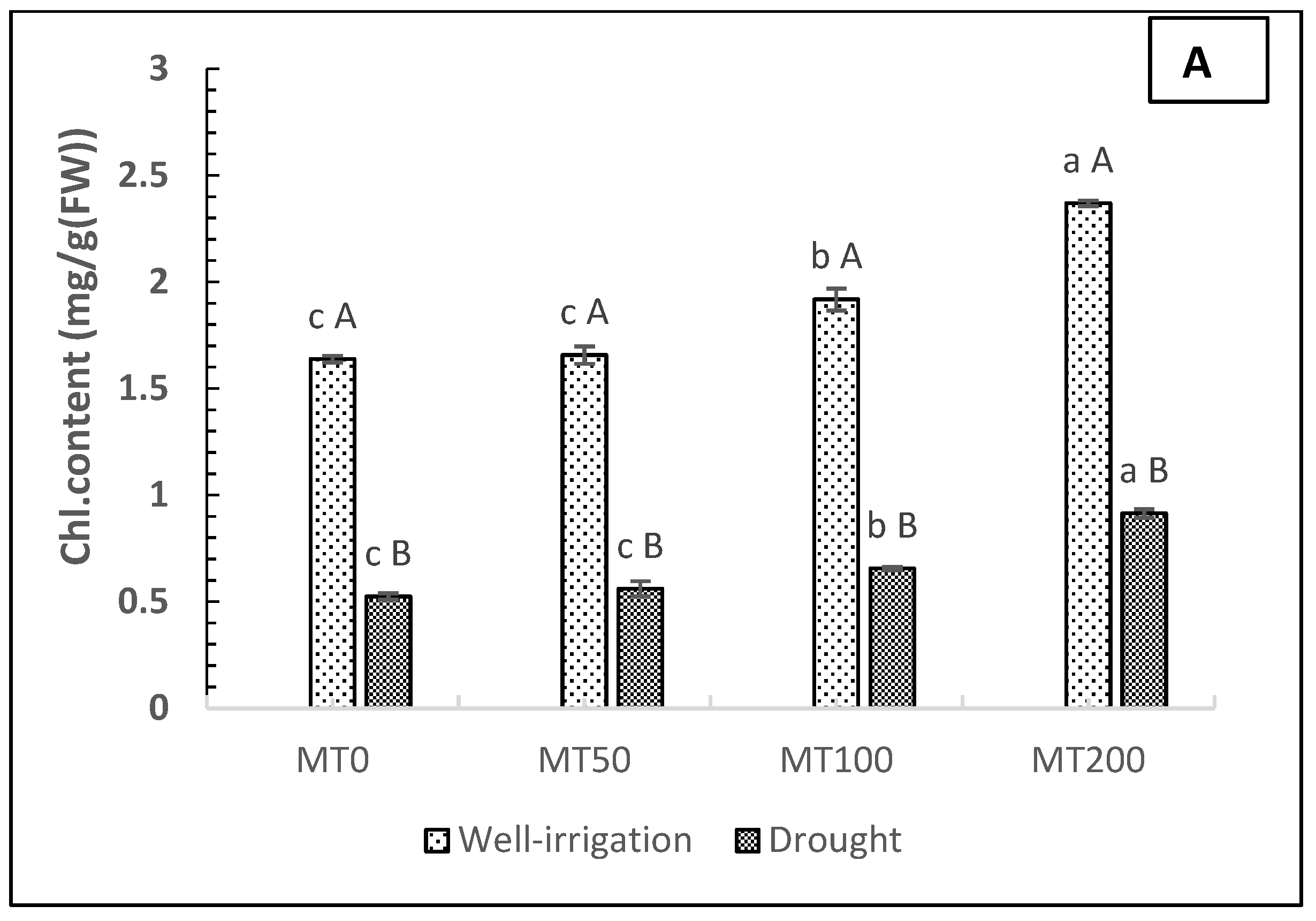

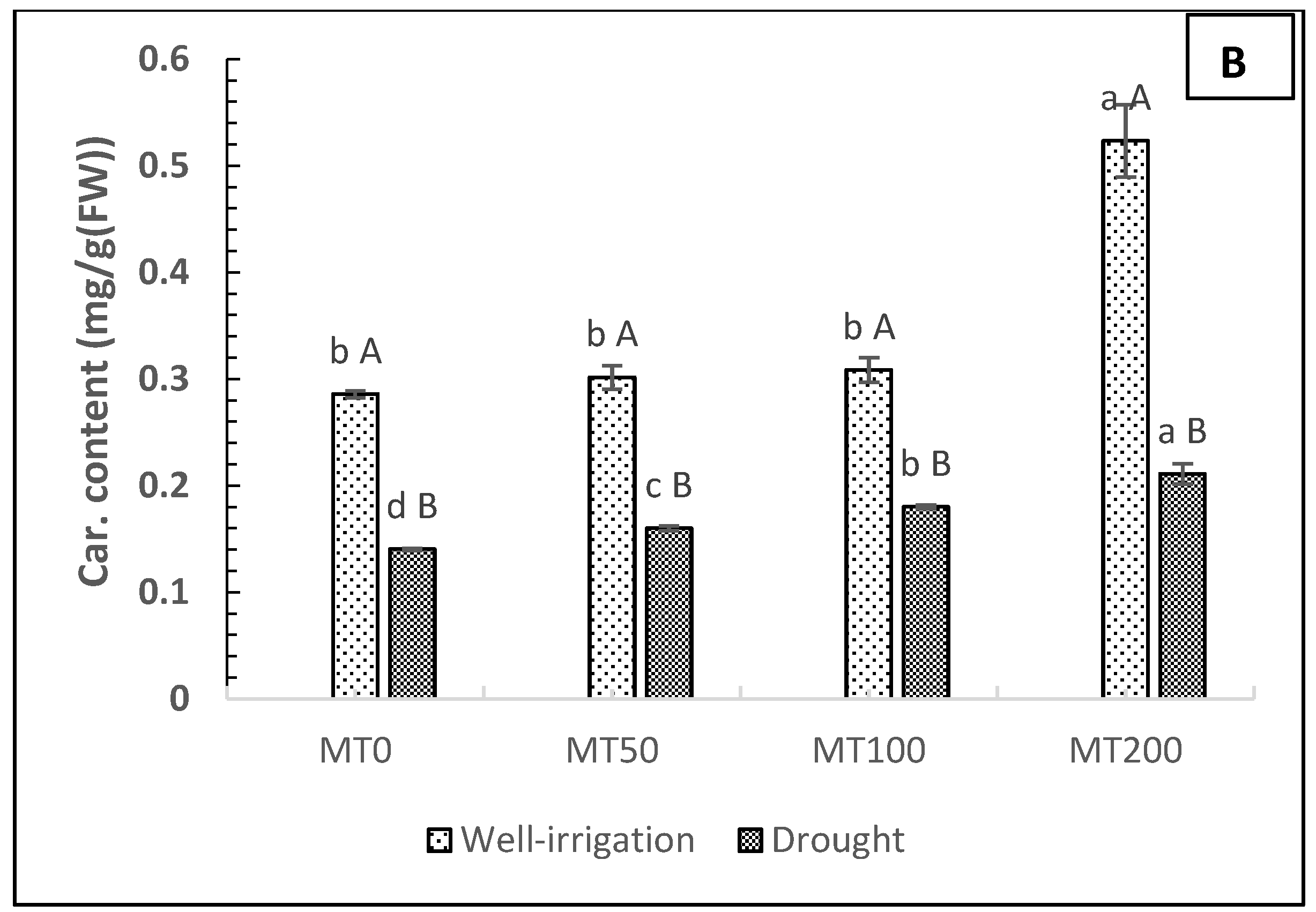

3.3. Changes in Photosynthetic Pigments

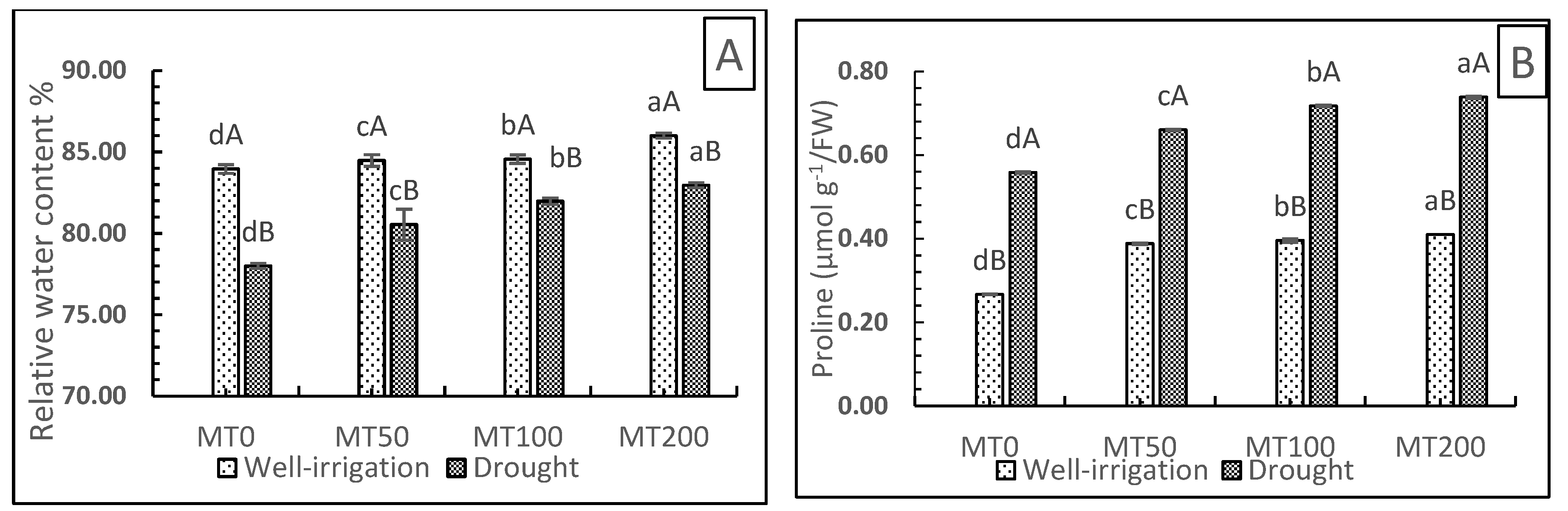

3.3. Exogenous MT Alters the RWC and Proline Content under Drought Stress

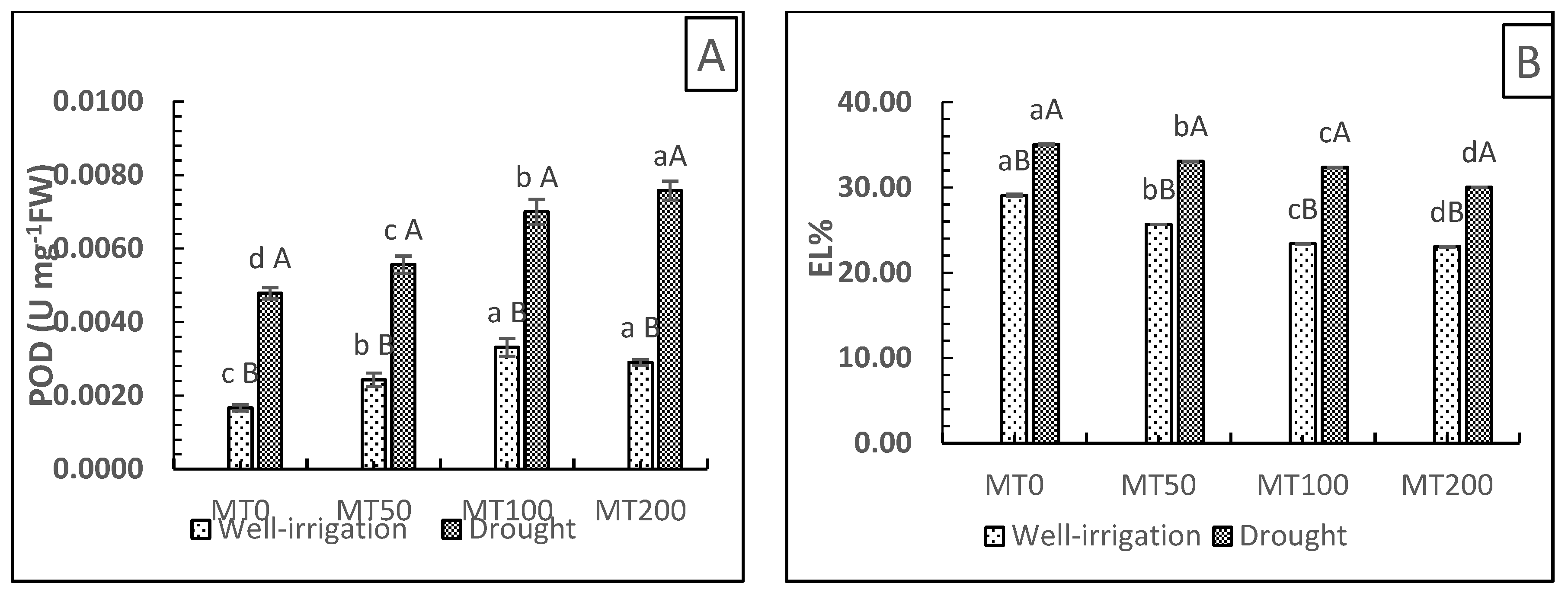

3.4. MT Modulates the Activity of Peroxidase Enzymes and Checks EL

3.5. DTI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karlsson, M. Producing Ravishing Ranunculus. Greenh. Prod. News January 2003, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Margherita, B.; Giampiero, C.; Pierre, D. Field Performance of Tissue-Cultured Plants of Ranunculus Asiaticus L. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 1996, 66, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, S.; Sun, Y.; Stock, M. Visual Quality, Gas Exchange, and Yield of Anemone and Ranunculus Irrigated with Saline Water. Horttechnology 2021, 31, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynet, J.A.; Le Nard, M. Ranunculus. In The physiology of flower bulbs; De Hertogh, A.A., Nard, M.L., Eds.; Elsevier, 1993; p. 795. [Google Scholar]

- Beruto, M.; Rabaglio, M.; Viglione, S.; Labeke, M.-C. Van; Dhooghe, E. Ranunculus. In Ornamental Crops; Springer, 2018; pp. 649–671. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, G.S.E.; Mostafa, Z.B.; Heidarzadeh, M. Estimation of Water Requirement about Some of the Most Dominant Green Areas in Isfahan, Using Lysimeter. In Proceedings of the Third National Conference on Green Spaces and Urban Landscape, Kish Island, Municipality and Degradation Organization of the Country (In Persian); Elsevier, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F.; Upreti, P.; Singh, R.; Shukla, P.K.; Shirke, P.A. Physiological Performance of Two Contrasting Rice Varieties under Water Stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tombesi, S.; Frioni, T.; Poni, S.; Palliotti, A. Effect of Water Stress “Memory” on Plant Behavior during Subsequent Drought Stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 150, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caser, M.; Chitarra, W.; D’Angiolillo, F.; Perrone, I.; Demasi, S.; Lovisolo, C.; Pistelli, L.; Pistelli, L.; Scariot, V. Drought Stress Adaptation Modulates Plant Secondary Metabolite Production in Salvia Dolomitica Codd. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 129, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidabadi, S.S.; Vander, W.J.; Sabbatini, P. Exogenous Melatonin Improves Glutathione Content, Redox State and Increases Essential Oil Production in Two Salvia Species under Drought Stress. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, Z.N.; Kazemi, F.; Tehranifar, A. Morpho-Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Four Ornamental Herbaceous Species to Water Stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2019, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M.A.; Shahid, R.; Ren, M.-X.; Naz, S.; Altaf, M.M.; Khan, L.U.; Tiwari, R.K.; Lal, M.K.; Shahid, M.A.; Kumar, R.; et al. Melatonin Improves Drought Stress Tolerance of Tomato by Modulating Plant Growth, Root Architecture, Photosynthesis, and Antioxidant Defense System. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S.A.; Tanveer, M.; Ashraf, U.; Hussain, S.; Shahzad, B.; Khan, I.; Wang, L. Effect of Progressive Drought Stress on Growth, Leaf Gas Exchange, and Antioxidant Production in Two Maize Cultivars. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 17132–17141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadak, M.S.; Abdalla, A.M.; Abd Elhamid, E.M.; Ezzo, M.I. Role of Melatonin in Improving Growth, Yield Quantity and Quality of Moringa Oleifera L. Plant under Drought Stress. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Jaleel, C.; Manivannan, P.; Wahid, A.; Farooq, M.; Al-Juburi, H.J. Somasundaram, R. Panneerselvam, R. Drought Stress in Plants: A Review on Morphological Characteristics and Pigments Composition. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2009, 11, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Munné-Bosch, S.; Mueller, M.; Schwarz, K.; Alegre, L. Diterpenes and Antioxidative Protection in Drought-Stressed Salvia Officinalis Plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2001, 158, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, H.; Cao, Y.; Weeda, S.; Ren, S.; Guo, Y.D. Roles of Melatonin in Abiotic Stress Resistance in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksup, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Supaibulwatana, K. Physiological and Comparative Proteomic Analyses of Thai Jasmine Rice and Two Check Cultivars in Response to Drought Stress. J. plant Interact. 2014, 9, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Garmdareh, S.E.H.; Behzad, A. Effects of Drought Stress on Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Characteristics of Stock Plant (Matthiola Incana L.). Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2019, 253, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraee, A.; Tehranifar, A. Evaluating the Potential Drought Tolerance of Pansy through Its Physiological and Biochemical Responses to Drought and Recovery Periods. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2020, 265, 109225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Manchester, L.C.; Liu, X.; Rosales-Corral, S.A.; Acuna-Castroviejo, D.; Reiter, R.J. Mitochondria and Chloroplasts as the Original Sites of Melatonin Synthesis: A Hypothesis Related to Melatonin’s Primary Function and Evolution in Eukaryotes. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 54, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarropoulou, V.N.; Therios, I.N.; Dimassi-Theriou, K.N. Melatonin Promotes Adventitious Root Regeneration in in Vitro Shoot Tip Explants of the Commercial Sweet Cherry Rootstocks CAB-6P (Prunus Cerasus L.), Gisela 6 (P. Cerasus × P. Canescens), and MxM 60 (P. Avium × P. Mahaleb). J. Pineal Res. 2012, 52, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Jiang, C.; Ye, T.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, R.; Chan, Z. Comparative Physiological, Metabolomic, and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal Mechanisms of Improved Abiotic Stress Resistance in Bermudagrass [Cynodon Dactylon (L). Pers.] by Exogenous Melatonin. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zeng, L.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, G.; Fu, G.; Ma, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zou, X.; Li, C. Exogenous Melatonin Alleviates Damage from Drought Stress in Brassica Napus L.(Rapeseed) Seedlings. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zeng, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, C. Relationship Between Proline and Hg2+-Induced Oxidative Stress in a Tolerant Rice Mutant. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009, 56, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Llorca, M.; Muñoz, P.; Müller, M.; Munné-Bosch, S. Biosynthesis, Metabolism and Function of Auxin, Salicylic Acid and Melatonin in Climacteric and Non-Climacteric Fruits. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zheng, G.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Hu, B.; Wang, H.; Wu, H.; Qian, Y.; Zhu, X.-G.; Tan, D.-X.; et al. Melatonin Delays Leaf Senescence and Enhances Salt Stress Tolerance in Rice. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 59, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, N.; Haq, Z.U.; Ali, H.; Munsif, F.; Hassan, S.S. ul; Bungau, S. Melatonin Pretreatment Alleviated Inhibitory Effects of Drought Stress by Enhancing Anti-Oxidant Activities and Accumulation of Higher Proline and Plant Pigments and Improving Maize Productivity. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, N.; Iqbal, S.; Hayat, F.; Raziq, A.; Ayaz, A.; Zaman, W. Melatonin in Micro-Tom Tomato: Improved Drought Tolerance via the Regulation of the Photosynthetic Apparatus, Membrane Stability, Osmoprotectants, and Root System. Life 2022, 12, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langaroudi, I.K.; Piri, S.; Chaeikar, S.S.; Salehi, B. Evaluating Drought Stress Tolerance in Different Camellia Sinensis L. Cultivars and Effect of Melatonin on Strengthening Antioxidant System. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2023, 307, 111517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.P.; Yang, S.J.; Chen, Y.Y. Effects of Melatonin on Photosynthetic Performance and Antioxidants in Melon during Cold and Recovery. Biol. Plant. 2017, 61, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chang, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Gu, X.; Wei, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Exogenous Melatonin Confers Salt Stress Tolerance to Watermelon by Improving Photosynthesis and Redox Homeostasis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Wellburn, A.R. Determinations of Total Carotenoids and Chlorophylls a and b of Leaf Extracts in Different Solvents 1983.

- Turk, H.; Erdal, S. Melatonin Alleviates Cold-Induced Oxidative Damage in Maize Seedlings by up-Regulating Mineral Elements and Enhancing Antioxidant Activity. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2015, 178, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.R.; Chaitanya, K.V.; Vivekanandan, M. Drought-Induced Responses of Photosynthesis and Antioxidant Metabolism in Higher Plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Ren, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, H. Protective Roles of Nitric Oxide on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) under Cadmium Stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 108, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ábrahám, E.; Hourton-Cabassa, C.; Erdei, L.; Szabados, L. Methods for Determination of Proline in Plants. In; 2010; Vol. 639, pp. 317–331.

- Sbei, H.; Shehzad, T.; Harrabi, M.; Okuno, K. Salinity Tolerance Evaluation of Asian Barley Accessions (Hordeum Vulgare L.) at the Early Vegetative Stage. J. Arid L. Stud. 2014, 24, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural Equation Models with Nonnormal Variables: Problems and Remedies. In Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc, 1995; pp. 56–75.

- Brown, M.B.; Forsythe, A.B. Robust Tests for the Equality of Variances. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1974, 69, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Testing Statistical Assumptions. In Asheboro, NC: Statistical Associates Publishing; 2012.

- Tabachnick, B.; Fidell, L. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Using Multivar. Stat. Pearson,Boston. IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Stat. Wind. 27.0. Armonk, NY IBM Corp. 2013.

- Armonk, N.Y. IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Google Search 2020.

- Olson, C.L. On Choosing a Test Statistic in Multivariate Analysis of Variance. Psychol. Bull. 1976, 83, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, G.T.; Linda, S.F. Using Multivariate Statistics; , 7th Edition. NY, NY: Pearson.ISBN-13: 9780135350904 ISBN-10: 0134790545., 2013.

- Sahin, U.; Ekinci, M.; Ors, S.; Turan, M.; Yildiz, S.; Yildirim, E. Effects of Individual and Combined Effects of Salinity and Drought on Physiological, Nutritional and Biochemical Properties of Cabbage (Brassica Oleracea Var. Capitata). Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2018, 240, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-J.; Zhang, N.; Yang, R.-C.; Wang, L.; Sun, Q.-Q.; Li, D.-B.; Cao, Y.-Y.; Weeda, S.; Zhao, B.; Ren, S.; et al. Melatonin Promotes Seed Germination under High Salinity by Regulating Antioxidant Systems, ABA and GA 4 Interaction in Cucumber ( Cucumis Sativus L.). J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, H.; Cao, Y.; Weeda, S.; Ren, S.; Guo, Y.-D. Roles of Melatonin in Abiotic Stress Resistance in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Li, M.; Liu, K.; Sui, N. Effects of Drought Stress on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Different Maize Varieties. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 7, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, Z.; Kim, W.S. Effect of Drought Stress on Shoot Growth and Physiological Response in the Cut Rose ‘Charming Black’ at Different Developmental Stages. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elewa, T.A.; Sadak, M.S.; Saad, A.M. Proline Treatment Improves Physiological Responses in Quinoa Plants under Drought Stress. Biosci. Res. 2017, 14, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq, M.; Akram, N.A.; Ashraf, M. Impact of Exogenously Applied Tocopherol on Some Key Physio-Biochemical and Yield Attributes in Mungbean [Vigna Radiata (L.) Wilczek] under Limited Irrigation Regimes. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.G.; El-Awadi, M.E.; Sadak, M.S.; El-Lethy, S.R. Comparison between the Physiological Role of Carrot Root Extract and Β$-Carotene in Inducing Helianthus Annuus L. Drought Tolerance. Asian J Biol Sci 2019, 12, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood, M.G.; Sadak, M.S. Physiological Role of Glycinebetaine in Alleviating the Deleterious Effects of Drought Stress on Canola Plants (Brassica Napus L.). Middle East J. Agric. Res 2014, 3, 943–954. [Google Scholar]

- Banon, S.; Ochoa, J.; Franco, J.A.; Alarcon, J.; Sanchez-Blanco, M.; Bañon, S.; Ochoa, J.; Franco, J.A.; Alarcón, J.J.; Sánchez-Blanco, M.J. Hardening of Oleander Seedlings by Deficit Irrigation and Low Air Humidity. Env. Exp Bot. 2006, 56, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, B.A.; El-Hariri, D.M.; Sadak, M.S.; El-Bassiouny, H.M.S. others Drought Stress Mitigation by Foliar Application of Salicylic Acid in Two Linseed Varieties Grown under Newly Reclaimed Sandy Soil. J Appl Sci Res 2012, 8, 3503–3514. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.; Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Trehalose-Induced Drought Stress Tolerance: A Comparative Study among Different Brassica Species. POJ 2014, 7, 271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Naeem, M.; Ahmad, R.; Ahmad, R.; Ashraf, M.; Ihsan, M.; Nawaz, F.; Athar, H.; Ashraf, M.; Abbas, H.; et al. Improving Drought Tolerance in Maize by Foliar Application of Boron: Water Status, Antioxidative Defense and Photosynthetic Capacity. Arch Agron Soil Sci 2018, 64, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafrańska, K.; Reiter, R.J.; Posmyk, M.M. Melatonin Application to Pisum Sativum L. Seeds Positively Influences the Function of the Photosynthetic Apparatus in Growing Seedlings during Paraquat-Induced Oxidative Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Huang, B.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Y.; Liao, J.; Yuan, S. Osystem II in Cold-Stressed Rice Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiab, F. Exogenous Melatonin Mitigates the Salinity Damages and Improves the Growth of Pistachio under Salinity Stress. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 43, 1468–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Latif Khan, A.; Shahzad, R.; Aaqil Khan, M.; Bilal, S.; Khan, A.; Kang, S.; Lee, I. Exogenous Melatonin Induces Drought Stress Tolerance by Promoting Plant Growth and Antioxidant Defence System of Soybean Plants. AoB Plants 2021, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Li, Q.T.; Chu, Y.N.; Reiter, R.J.; Yu, X.M.; Zhu, D.H.; Zhang, W.K.; Ma, B.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, J.S.; et al. Melatonin Enhances Plant Growth and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Soybean Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Awadi, M.; Sadak, M.; Dawood, M.; Khater, M.; Elashtokhy, M. Amelioration the Adverse Effects of Salinity Stress by Using γ- Radiation in Faba Bean Plants. Bull NRC 2017, 41, 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Cui, W.; Kamran, M.; Ahmad, I.; Meng, X.; Wu, X.; Su, W.; Javed, T.; El Hamed, A.; Zhikuan, S.; et al. Exogenous Application of Melatonin Induces Tolerance to Salt Stress by Improving the Photosynthetic Efficiency and Antioxidant Defense System of Maize Seedling. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadak, M.S.; Ramadan, A.A.E.-M. Impact of Melatonin and Tryptophan on Water Stress Tolerance in White Lupine (Lupinus Termis L.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Ruiz, J.; Cano, A.; Arnao, M.B. Melatonin: A Growth-Stimulating Compound Present in Lupin Tissues. Planta 2004, 220, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeda, S.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, X.; Ndip, G.; Guo, Y.; Buck, G.; Fu, C.; Ren, S. Arabidopsis Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Key Roles of Melatonin in Plant Defense Systems. PLoS One 2014, 9, e93462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, R.G.; Else, M.A.; Cameron, R.W.; Davies, W.J. Water Deficits Promote Flowering in Rhododendron via Regulation of Pre and Post Initiation Development. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2009, 120, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.C.; Takeno, K. Stress-Induced Flowering. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 944–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimonidou-Pavlidou, D. Effect of Irrigation and Shading at the Stage of Flower Bud Appearance. Acta Hortic. 2001, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Q.; Reiter, R.; He, C. Melatonin Mediates the Stabilization of DELLA Proteins to Repress the Floral Transition in Arabidopsis. J Pineal Res 2016, 60, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, P.; Cheng, H.; Liu, W.; Xing, X.; Guan, Z.; Fang, W.; Chen, S.; et al. Strigolactone Represses the Synthesis of Melatonin, Thereby Inducing Floral Transition in Arabidopsis Thaliana in an FLC-Dependent Manner. J Pineal Res 2019, 67, e12582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, M.B.A.J.H.; Arnao, M.B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Melatonin in Flowering, Fruit Set and Fruit Ripening. Plant Reprod. 2020, 33, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnao, M.B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Protective Effect of Melatonin against Chlorophyll Degradation during the Senescence of Barley Leaves. J. Pineal Res. 2009, 46, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Din, J.; SU, K.; J, A.; AR, G. Physiological and Agronomic Response of Canola Varieties to Drought Stress. J An Plant Sci. 2011, 21, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, H.; Baig, M.; Bhatt, R. Effect of Moisture Stress on Chlorophyll Accumulation and Nitrate Reductase Activity at Vegetative and Flowering Stage in Avena Species. Agric Sci Res J 2012, 2, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum, F.; Yaseen, M.; Rasul, E.; Wahid, A.; S, A. Water Stress in Barley. I. Effect on Chemical Composition and Chlorophyll Content. Pak J Agric Sci 2003, 40, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, B.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Gao, T.; Zhao, Q.; Ma, F.; Li, C. Long-Term Exogenous Application of Melatonin Improves Nutrient Uptake Fluxes in Apple Plants under Moderate Drought Stress; Elsevier B.V., 2018; Vol. 155; ISBN 8629870826.

- Safari, M.; Mousavi-Fard, S.; Rezaei Nejad, A.; Sorkheh, K.; Sofo, A. Exogenous Salicylic Acid Positively Affects Morpho-Physiological and Molecular Responses of Impatiens Walleriana Plants Grown under Drought Stress. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiliani, J.; D’Andrea, L.; Lorena Falcone Ferreyra, M.; Maulión, E.; Rodriguez, E.; Rodriguez-Concepción, M.; Casati, P. A Role for β,β-Xanthophylls in Arabidopsis UV-B Photoprotection. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 4921–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis Castañares, J.; Alberto Bouzo, C. Effect of Exogenous Melatonin on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth in Melon (Cucumis Melo L.) Under Salt Stress. Hortic. Plant J. 2019, 5, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, A.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Niu, Y.; Liu, S.; Mi, G.; Gao, Q. Reducing Basal Nitrogen Rate to Improve Maize Seedling Growth, Water and Nitrogen Use Efficiencies under Drought Stress by Optimizing Root Morphology and Distribution. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 212, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SoltysKalina, D.; Plich, J.; Strzelczyk-Zyta, D.; Sliwka, J.; Marczewski, W. Effect of Drought Stress on the Leaf Relative Water Content and Tuber Yield of a Half-Sib Family of ‘Katahdin’-Derived Potato Cultivars. Breed. Sci. 2016, 66, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvan, S. The Effects of Drought Stress on Yield, Relative Water Content, Proline, Soluble Carbohydrates and Chlorophyll of Bread Wheat Cultivars. J Anim Plant Sci. 2010, 8, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Loka, D.A.; Zhao, W.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, L. Effects of Single and Combined Exogenous Application of Abscisic Acid and Melatonin on Cotton Carbohydrate Metabolism and Yield under Drought Stress. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 176, 114302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y. Exogenous Melatonin Improves Seedling Health Index and Drought Tolerance in Tomato. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 77, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegah, S.; Chehrazi, M.; Albaji, M. Effects of Drought Stress on Growth and De- Velopment Frankinia Plant (Frankinia Leavis). Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 19, 659–665. [Google Scholar]

- Seki, M.; Umezawa, T.; Urano, K.; Shinozaki, K. Regulatory Metabolic Networks in Drought Stress Responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biolol. 2007, 10, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcińska, I.; Czyczyło-Mysza, I.; Skrzypek, E.; Filek, M.; Grzesiak, S.; Grzesiak, M.T.; Janowiak, F.; Hura, T.; Dziurka, M.; Dziurka, K.; et al. Impact of Osmotic Stress on Physiological and Biochemical Characteristics in Drought-Susceptible and Drought-Resistant Wheat Genotypes. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013, 35, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Beneficial Effects of Exogenous Melatonin on Overcoming Salt Stress in Sugar Beets (Beta Vulgaris L.). Plants 2021, 10, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Lu, B.; Liu, L.; Duan, W.; Meng, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, H.; et al. Exogenous Melatonin Improves the Salt Tolerance of Cotton by Removing Active Oxygen and Protecting Photosynthetic Organs. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, R. Plant Responses to Water Stress: Role of Reactive Oxygen Species. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 1741–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozgur, R.; Uzilday, B.; Sekmen, A.H.; Turkan, I. Reactive Oxygen Species Regulation and Antioxidant Defence in Halophytes. Funct. Plant Biol. 2013, 40, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiztugay, E.; Ozfidan-Konakci, C.; Kucukoduk, M.; Tekis, S.A. The Impact of Selenium Application on Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Systems in Zea Mays Roots Treated with Combined Osmotic and Heat Stress. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2017, 63, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Numan, M.; Khan, A.L.; Lee, I.-J.; Imran, M.; Asaf, S.; Al-Harrasi, A. Melatonin: Awakening the Defense Mechanisms during Plant Oxidative Stress. Plants 2020, 9, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Fan, J.; Xie, Y.; Amombo, E.; Liu, A.; Gitau, M.M.; Khaldun, A.B.M.; Chen, L.; Fu, J. Comparative Photosynthetic and Metabolic Analyses Reveal Mechanism of Improved Cold Stress Tolerance in Bermudagrass by Exogenous Melatonin. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 100, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, N.; Alyammahi, O.; Nasreddine, S.; Alhassani, A.; Gururani, M.A. Melatonin Positively Influences the Photosynthetic Machinery and Antioxidant System of Avena Sativa during Salinity Stress. Plants 2019, 8, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Chen, Y.; Tan, D.-X.; Reiter, R.J.; Chan, Z.; He, C. Melatonin Induces Nitric Oxide and the Potential Mechanisms Relate to Innate Immunity against Bacterial Pathogen Infection in Arabidopsis. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 59, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saneoka, H.; Moghaieb, R.E.; Premachandra, G.S.; Fujita, K. Nitrogen Nutrition and Water Stress Effects on Cell Membrane Stability and Leaf Water Relations in Agrostis Palustris Huds. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004, 52, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkash, V.; Singh, S. A Review on Potential Plant-Basedwater Stress Indicators for Vegetable Crops. Sustain. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catala, A. The Ability of Melatonin to Counteract Lipid Peroxidation in Biological Membranes. Curr. Mol. Med. 2007, 7, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Chen, Y.-E.; Zhao, Y.-Q.; Ding, C.-B.; Liao, J.-Q.; Hu, C.; Zhou, L.-J.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Yuan, S.; Yuan, M. Exogenous Melatonin Alleviates Oxidative Damages and Protects Photosystem II in Maize Seedlings under Drought Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, C.; Mayo, J.C.; Sainz, R.M.; Antolin, I.; Herrera, F.; Martin, V.; Reiter, R.J. Regulation of Antioxidant Enzymes: A Significant Role for Melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2004, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, R.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Ashraf, M.; Waraich, E.A. Sunflower (Helianthus Annuus L.) Response to Drought Stress at Germination and Seedling Growth Stages. Pak. J. Bot 2009, 41, 647–654. [Google Scholar]

| Substrate type | Peat moss |

|---|---|

| pH | 6 |

| EC (cm/mmhos) | 0.4–0.5 |

| Humidity % | 50-65 |

| Organic matter (OM)% | >90 |

| Macroelement (1 kg/m3) | |

| N:P:K | 14:10:18 |

| Microelement (mg/kg) | |

| Zn | 32.45 |

| Cu | 15.6 |

| Cd | 0.42 |

| Pb | 15.28 |

| Mo | 0.10 |

| Ni | 8.75 |

| Cr | 0.70 |

| Hg | <0.01 |

| As | 0.112 |

| Co | 1.11 |

| Cl | <0.2 |

| Na | <0.1 |

| Treatments | Shoot length (cm) | No. of leaves | Area/leaf (cm2) | Fresh weight (g) | Dry weight (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-irrigated (W) | ||||||

| MT (µM) | 0 | 18.87 ± 0.18 bA | 6.67 ± 0.49 bA | 47.97 ± 0.05 dA | 18.19 ± 0.39 cA | 3.12 ± 0.19 bA |

| 50 | 19.07 ± 0.27 bA | 7.33 ± 0.49 aA | 54.49 ± 0.11 cA | 18.15 ± 0.15 cA | 3.12 ± 0.07 bA | |

| 100 | 21.49 ± 0.35 aA | 7.67 ± 0.49 aA | 55.31 ± 0.08 bA | 18.82 ± 0.26 bA | 3.17 ± 0.14 bA | |

| 200 | 21.55 ± 0.34 aA | 7.73 ± 0.46 aA | 55.60 ± 0.18 aA | 21.73 ± 0.27 aA | 3.12 ± 0.19 aA | |

| Drought (D) | ||||||

| MT(µM) | 0 | 13.97 ± 0.47 cB | 4.60 ± 0.51 cB | 18.15 ± 0.20 dB | 11.92 ± 0.17 dB | 1.47 ± 0.06 dB |

| 50 | 15.75 ± 0.37 bB | 5.20 ± 0.56 bB | 21.61 ± 0.16 cB | 13.99 ± 0.09 cB | 1.63 ± 0.09 cB | |

| 100 | 16.78 ± 0.30 aB | 5.73 ± 0.70 abB | 28.78 ± 0.22 bB | 15.92 ± 0.13 bB | 1.85 ± 0.06 bB | |

| 200 | 17.09 ± 0.39 aB | 5.93 ± 0.46 aB | 29.56 ± 0.17 aB | 17.01 ± 0.10 aB | 2.01 ± 0.12 aB | |

| Traits | DTI (%) |

|---|---|

| Shoot length | 74.02 ± 2.83 ef |

| Leaf number | 69.37 ± 9.35 ef |

| Leaf area | 37.84 ± 0.39 gh |

| Shoot fresh weight | 65.53 ± 1.73 f |

| Shoot dry weight | 47.20 ± 3.48 g |

| Time of flower bud emergence | 79.31 ± 2.30 ed |

| Total chlorophyll content | 32.00 ± 1.02 h |

| Carotenoid content | 49.12 ± 0.58 g |

| Relative water content (RWC) | 92.90 ± 0.45 d |

| Proline content | 207.40 ± 0.30 b |

| Peroxidase activity (POD) | 282.35 ± 10.53 a |

| Electrolyte leakage (EL) | 120.49 ± 0.72 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).